How do social movements pursue social and policy change? This question has led to extensive sociological and political science research. Our study aims to investigate this question by focusing on one specific means of action used by some non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to pursue their objective—namely, that of litigation. Taking Belgium and the field of antidiscrimination as a case study, our research confirms previous analyses in showing that the characteristics of the legal environment do impact on their choice of whether or not to go to court. We find that the gradual creation of new legal opportunities over the last twenty years in this country has been accompanied by a significant increase in the number of lawsuits brought by NGOs in relation to antidiscrimination. But our findings also bring new elements to light, by showing that various organizations situated in the same legal environment use legal action differentially: some organizations resort to the judicial system more often than others and demonstrate a higher level of mastery of legal procedures. Litigation also holds a different place in the tactical repertoire of these NGOs: for some, it is a central mode of action, while, for others, it is only a marginal one. Our research identifies some of the factors that explain these differences.

This article explores the conditions under which a selected number of non-profit organizations have used litigation in the last decade to combat discrimination, based on both a measure of the change over time of the number of lawsuits brought by NGOs in relation to discrimination and interviews with activists from various NGOs active in the antidiscrimination field in Belgium, lawyers, and equality agency officers. In contrast with previous studies that have sought to explain why some NGOs turn to litigation while others do not (Conant et al. Reference Conant, Hofmann, Soennecken and Vanhala2018; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2018; Hofmann and Naurin Reference Hofmann and Naurin2021), this article focuses on organizations that have all resorted at least once to legal action. Furthermore, whereas previous research on legal mobilization has usually focused on lawsuits brought before higher courts or European judicial institutions, we consider, like Susan Sterett and Laura Mateczun (Reference Sterett and Mateczun2020), that litigation before lower courts is as important to understand such phenomena. We thus take into account litigious activities of the organizations studied before lower level courts as well as higher courts and European bodies. Our findings show that, among such organizations, significant differences exist regarding their relation to law and the way in which they use it. We argue that the legal opportunities that are available are used differentially by NGOs depending on two factors in particular: their position as an insider or outsider in the political realm and their possession of legal resources. We also contend that the interplay between these factors is crucial to explain these differences.

The first section of this article lays out our theoretical framework. We specify how we envisage litigation as a particular form of legal mobilization and develop the concepts of legal opportunities, political insiders and outsiders, and legal resources. In the second section, we explain why we chose to focus on Belgian NGOs combating discrimination and the methods used, before describing in the third section the change in legal opportunity structures in Belgium. We then present our empirical analysis, which is based both on a quantitative measure of NGOs’ legal activism in Belgium and on a qualitative study of how a sample of NGOs use litigation. Finally, we propose a typology of NGOs that could be transposed to other contexts and other types of organizations in order to compare the differential use of legal opportunities by interest groups.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: EXPLORING THE DIFFERENTIAL USE OF LITIGATION BY NGOs

We consider litigation as a particular form of legal mobilization. Various factors have been put forward in the literature to explain the use of this tactic by social movements. Theories highlighting the importance of legal opportunities, organizations’ insider or outsider position, and their legal resources proved especially relevant to our research.

Litigation as a Form of Legal Mobilization

The concept of legal mobilization has been used in the socio-legal literature to capture the various processes through which individuals or collective actors “invoke legal norms, discourse, or symbols to influence policy or behaviour” (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2011, 5). Scholars, however, disagree about the range of activities that constitute legal mobilization (Lehoucq and Taylor Reference Lehoucq and Taylor2019). Some authors understand this term narrowly, as referring to the use of litigation by social movements or individuals (Black Reference Black1973; Epp Reference Epp1998; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2011; Munoz and Moya Reference Munoz, Moya, Sterett and Walker2019). Other scholars, by contrast, approach legal mobilization more broadly as encompassing any invocation of legal norms or arguments by a social movement, or even by ordinary people, to frame their claim (McCann Reference McCann1994; Morrill et al. Reference Morrill, Edelman, Tyson and Arum2010; Lemaitre and Sandvik Reference Lemaitre and Sandvik2015; Abbot and Lee Reference Abbot, Lee, Abbot and Lee2021).

We agree with the second group of authors that limiting the term “legal mobilization” to litigation is too reductive. Where a social movement resorts to legal arguments and discourse as major instruments to promote their political and social objectives, it is putting law at the service of mobilization. We thus consider litigation as one possible form of legal mobilization although probably the most conspicuous one.

Legal Opportunities: An Incomplete Explanation

Socio-legal scholars have developed the concept of “legal opportunity structure” to capture the specificities of a country’s legal system and explore the influence it may have on a group’s decision whether or not to use litigation as a means of collective action (Hilson Reference Hilson2002; Andersen Reference Andersen2006; Rodriguez Cordero Reference Rodriguez Cordero2006; Evans Case and Givens Reference Evans Case and Givens2010; De Fazio Reference De Fazio2012). Legal opportunity structures include various elements inherent to the legal system, such as the legal standing of NGOs, available remedies and legal rules that litigation can be based on, the mandate of particular courts, and rules regarding legal costs (Andersen Reference Andersen2006). These structures can be either relatively open or relatively closed to civil society action. When they are open, it means that the strategic use of the legal system by non-governmental organizations to advance their cause is facilitated. When they are closed, legal action is more difficult, if not impossible (Evans Case and Givens Reference Evans Case and Givens2010, 223). Gianluca De Fazio’s (Reference De Fazio2012) analysis of the use of litigation by marginalized groups in the Southern United States and Northern Ireland provides a good illustration of this concept. He showed that, although both groups experienced discrimination, African Americans in the United States were more likely than Catholics in Northern Ireland to turn to the legal system to pursue their rights because, in the United States, courts were more accessible and the judiciary was more receptive to rights claims.

Early works on legal opportunities tended to describe the legal environment of NGOs as uniformly influencing the action of organizations situated in a given legal context. Comparing different institutional settings or time periods, they tended to assume that NGOs situated in the same legal system would turn to litigation in the same way because their choice would be determined by their legal environment (De Fazio Reference De Fazio2012). More recent studies have considered the influence of these legal features on the NGOs’ strategies in a more dynamic way, focusing not only on the legal environment as such but also on how the agents acting in these contexts relate to them. They have emphasized that various NGOs in the same country may position themselves differently toward the legal system, some engaging in lawsuits while others do not (Hilson Reference Hilson2002; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2009; Arrington Reference Arrington2019; Munoz and Moya Reference Munoz, Moya, Sterett and Walker2019). This approach assumes that features of the legal context become opportunities only when groups perceive them as such and decide to use them to advance their objectives (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2018).

Moreover, some NGOs may develop strategies aimed at transforming the legal environment itself in order to enlarge the opportunities open to them. In her study on the use of litigation by environmental organizations in the United Kingdom, Lisa Vanhala (Reference Vanhala2012) has shown that going to court may be aimed not only at obtaining a ruling favorable to the cause on the substance of the matter at hand but also at enhancing access to justice for social movement groups (for example, through a change of rules governing legal standing). Thus, “movement activists are not passive actors simply responding to externally-imposed legal opportunities but instead play a role in creating their own legal opportunities” (525).

Concurring with this approach, we consider legal opportunities both as features of the environment that influence NGOs’ modes of intervention and as a target for action for (some) NGOs that may seek to create or enlarge those opportunities. However, our study takes this more dynamic perspective further, as we explore in detail the varying attitudes that different NGOs in the same context develop toward their legal environment and try to understand the reasons for these differences. We thus view legal opportunities as a necessary, but not sufficient, element to explain the use of litigation by NGOs.

THE INSIDER/OUTSIDER POSITION: UNRAVELING THE CONTRADICTORY FINDINGS IN THE LITERATURE

Among the other factors put forward to explain the choice of a group whether or not to use litigation, the influence of the political environment has attracted major attention. This aspect has been approached by many authors in terms of “political opportunity structure” (McAdam Reference McAdam1982; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1986), a concept proposed in the social movement literature to describe and analyze how the features of the surrounding political system enhance or inhibit prospects for mobilization (Meyer and Minkoff Reference Meyer and Minkoff2004, 1457) and impact on the tactical choices that civil society organizations make to pursue their objectives (Hilson Reference Hilson2002). Defined as the “consistent—but not necessarily formal or permanent—dimensions of the political environment that provide incentives for people to undertake collective action by affecting their expectations for success or failure” (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1994, 85), it has mainly been used to explain variations of activist claims and strategies over time and across institutional contexts (Meyer and Minkoff Reference Meyer and Minkoff2004, 1458). This approach, however, has been criticized for its tendency to focus on general, structural features of the political system, making it ill-suited to account for disparities in attitudes and strategies among organizations in a given political setting (Hilson Reference Hilson2002, 242).

Other scholars have emphasized that NGOs located in the same political environment may hold different degrees of access to, and influence on, the policy-making process. Scholarship has distinguished between so-called “insiders”—that is, groups with privileged access and capacity of influence—and “outsiders”—that is, groups with limited or no access and capacity of influence (Maloney, Jordan, and McLaughlin Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994; Abbot and Lee Reference Abbot, Lee, Abbot and Lee2021). It has been noted that the acquisition of insider or outsider position depends both on the acceptance of the group by the political elite and on the decision of the group itself. It has further been observed that, to the extent that such status is chosen by a group, it is a choice made under the influence of various factors, including not only its sense as to which type of strategy will produce favorable results but also its membership and sources of funding (Maloney, Jordan, and McLaughlin Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994). In our research, one aspect appeared crucial in this regard—that is, the organization’s perception of the attitude of the political elite toward its cause. Our findings suggest that, where a group perceives the political environment as being at least partially favorable toward its objectives, it is likely to use insider strategies to promote its goals, whereas when it sees this environment as unfavorable, it will tend to adopt an outsider position. This concurs with the observation made by several authors that the concept of political opportunities has a subjective dimension: it is not only political opportunities as such that influence social movements but also how activists in social movements perceive these political opportunities (Giugni and Grasso Reference Giugni and Grasso2018). This perception may be congruent with objectively existing political opportunities, but, in some cases, there is a mismatch between perceptions and reality (Kurzman Reference Kurzman1996, 164).

Previous studies that have tried to assess whether political insiders or outsiders are more likely to resort to litigation have led to contradictory empirical findings. Some of them have found that groups that are disadvantaged in the traditional political arena are more likely to turn to litigation for lack of other options (Scheppele and Walker Reference Scheppele, Walker and Walker1991; Alter and Vargas Reference Alter and Vargas2000). On the opposite side, other research has shown that insider groups are more likely to use lawsuits because they have more resources and an easier access to courts (Coglianese Reference Coglianese1996; Börzel Reference Börzel2006; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2016). Recent studies have argued that both insider and outsider groups are susceptible of resorting to litigation (Hofmann and Naurin Reference Hofmann and Naurin2021), depending on the institutional and political context, their organizational identity and aims (Munoz and Moya Reference Munoz, Moya, Sterett and Walker2019), or how they position themselves in the competition for resources and visibility (Jacquot and Vitale Reference Jacquot and Vitale2014). The range of factors cited, however, is very wide and does not explain how the insider/outsider position matters in an organization’s decision to use litigation as a strategy to promote its goals.

Legal Resources: Exploring Further When and Why NGOs Develop Legal Resources

The extent of an NGO’s resources constitutes another factor that has been highlighted as being likely to influence its use of litigation (Börzel Reference Börzel2006). Various studies have demonstrated that groups that are well endowed with human and financial resources are more likely to turn to litigation than those with limited resources (Bouwen and McCown Reference Bouwen and McCown2007).

Some of these studies have highlighted the special importance of one specific set of resources—namely, legal resources. By this, we mean the various resources that allow NGOs to have knowledge of the law and the legal system. The impact of this type of resource deserves to be studied autonomously from that of others as they do not necessarily coincide: some organizations may have very limited human and financial resources and yet a significant legal capacity (Pedriana and Stryker Reference Pedriana and Stryker2004). Moreover, legal resources differ from human and financial resources in that they are not necessarily internal to the organization: legal resources include not only the development of legal expertise within the entity in question through the recruitment of in-house lawyers (internal resources) but also close connections with networks of legal professionals working in areas of interest to the organization, such as cause lawyers (external resources) (Epp Reference Epp1998; Sarat and Scheingold Reference Sarat and Scheingold2006; Israël Reference Israël2009).

One question, however, has been under-explored in the literature—that of when and why NGOs develop legal resources. Do organizations tend to turn to litigation because they already possess legal resources, or do they invest in acquiring such resources because they have decided to use legal action? Another issue that needs further attention is the potential link between the possession of legal resources and a NGO’s propensity to use legal framing to articulate its claims, knowing that this latter element has also been highlighted in the literature as a factor favoring the use of litigation by an organization (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2009; Hayes and Doherty Reference Hayes and Doherty2014).

By taking into account legal opportunities, insider or outsider position, and legal resources, our study seeks to understand why some NGOs use litigation as a means of action as well as why some do so differently than others. Favorable legal opportunities increase the chances to see organizations going to court to advance their cause. Yet not all NGOs situated in the same legal context turn to the judicial system, and those that do so do not display the same relation to law and legal action. This article aims to demonstrate empirically how these different elements shape NGOs’ attitudes and strategies toward the use of litigation as a means of action. It proposes ultimately a typology of NGOs that we hope could be transposed to other groups and other contexts.

CASE SELECTION AND METHODS

Case Selection

Our study focuses on NGOs based in Belgium that have used litigation to combat discrimination relating to one of the four following criteria: race/ethnic origin, sex, disability, and religion. Belgium presents a special interest for studying the use of litigation by non-profit organizations for two main reasons. First, Belgium is a neo-corporatist system in which interest groups such as businesses, labor unions, and NGOs play a key role in political and economic processes. This means that civil society organizations are regularly consulted in decision-making processes and that some of them have been entrusted with the running of certain public service activities (Faniel, Gobin, and Paternotte Reference Faniel, Gobin and Paternotte2020). The political opportunity structure is thus relatively open for NGOs, and a number of them are granted an insider position in the political process. Second, while its legal framework was for a long time unfavorable to the use of courts by NGOs, Belgium has undergone substantial changes from the 1990s onwards, leading to the progressive opening of legal opportunity structures in this respect. It thus provides a particularly suitable case for studying why some NGOs, although located in a country where such organizations generally have relatively easy access to the political arena, nonetheless decide to seize emerging legal opportunities and use litigation.

The field of antidiscrimination appears especially relevant for our purposes as it is a cause that, in many countries, has given rise to significant legal mobilization by NGOs. The United States and the United Kingdom provide particularly notable examples (Burstein Reference Burstein1991; Alter and Vargas Reference Alter and Vargas2000). Moreover, the European Union (EU), of which Belgium is a member state, adopted a series of antidiscrimination directives in 2000, 2004, and 2006, which established an obligation for member states to recognize the legal standing of NGOs in antidiscrimination cases (Evans Case and Givens Reference Evans Case and Givens2010).Footnote 1 We selected four discrimination grounds—race/ethnic origin, sex, disability, and religion—because we wanted to include NGOs that are active in different fields related to antidiscrimination. We chose grounds that are all included among the criteria covered by EU antidiscrimination law to facilitate transnational comparison. Furthermore, among the grounds protected under EU law, we selected those that, at the Belgian level, generate the highest number of legal actions.Footnote 2

These four criteria, however, have had different legal trajectories in Belgian law and are associated with diverse histories of mobilization. Sex and race/ethnic origin are the oldest discrimination grounds recognized under Belgian law. In both cases, the enactment of the first legal provisions relating to them—in 1978 and 1981 respectivelyFootnote 3 —resulted in large part from external legal developments—namely, the passing of the first sex discrimination EU directives in the 1970sFootnote 4 and the adoption in 1965 of the United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.Footnote 5 The prohibition of discrimination based on disability and religion is much more recent in Belgian law. It was introduced in 2003 in the context of the transposition of Council Directive 2000/78 on antidiscrimination.Footnote 6 Sex and race/ethnic origin antidiscrimination laws were profoundly reformed in the same period to comply with other EU antidiscrimination directives.Footnote 7 Besides, these four grounds generate different levels of support among the general public and political actors. We will come back to this later in the article.

Methods

Case Law Research

We have created, for the first time in Belgium, an original database that includes the cases brought by Belgium-based NGOs in relation to race/ethnic origin, sex, disability, and religious discrimination between 1981 and 2019 before ordinary courts, the Constitutional Court, and the European Committee of Social Rights (see Appendix 1). For the European Committee of Social Rights and the Constitutional Court, the search was facilitated by the fact that all their decisions/judgments, as well as pending cases, are published on their website. For the Constitutional Court, we screened all applications submitted by legal persons or de facto organizations to identify those that meet three criteria: (1) they were introduced by one or several NGOs; (2) the claimant NGOs were defending a public interest or a marginalized group and not merely the particular interest of the organization or its members; and (3) the claimant NGOs alleged discrimination based on one of our selected criteria.

The search for relevant ordinary court judgments was more difficult as only a portion of Belgian ordinary court rulings are published in legal journals or public databases. The two Belgian equality agencies—the Interfederal Center for Equal Opportunites (or Unia) and the Institute for the Equality of Women and Men (IEWM)Footnote 8 —are supposed to collect all judicial decisions relating to their mandate and make them available on their website, but, in practice, their respective databases are incomplete. Hence, besides Unia and the IEWM’s databases, we also consulted the three Belgian general legal databases: Stradalex, Jura, and Jurisquare. Additionally, we used the data collected through a parallel research project in the framework of which all courts in the country were contacted and asked to send judgments issued within their jurisdiction in relation to discrimination based on EU law grounds.Footnote 9 We focused here on cases brought by NGOs based on the antidiscrimination legislation. Our research began in 1981, the year in which the Act Forbidding Certain Acts Inspired by Racism and Xenophobia (Antiracism Act),Footnote 10 which was the first statute providing legal standing to NGOs in the field of antidiscrimination, was adopted.

We are aware of course that a NGO may be involved in a legal case in another capacity than as a complainant. It can provide financial, legal, and practical support to individual complainants bringing the case in their own name. It may also participate in a legal action through the filing of a third-party intervention (a device comparable to the amicus curiae in the United States). Such cases, however, cannot be identified in a systematic way through legal research tools available in Belgium. Accordingly, our general case law database only includes cases where a NGO acted as a complainant. In the second part of our research, by contrast, when we focused on a sample of NGOs, we were able to take into account instances of informal support provided by a NGO to individual plaintiffs and third-party interventions.

Our database does not include cases submitted before the Council of State (Conseil d’Etat/Raad van State), an administrative jurisdiction that reviews administrative acts. In our discussion with lawyers and activists interviewed for this research, we were told that this legal body had been little used by NGOs in the field of antidiscrimination. Moreover, there were significant practical obstacles in identifying relevant rulings issued by the Council of State between 1981 and 2019; notably, its online case law database is exhaustive only from 1996 onwards, and it does not allow a user to carry out a search based on the nature of the applicant (for example, NGOs or legal persons). For all these reasons, we decided to restrict our general case law research to ordinary courts, the Constitutional Court, and the European Committee of Social Rights.

Sample of NGOs and Interviews with Activists

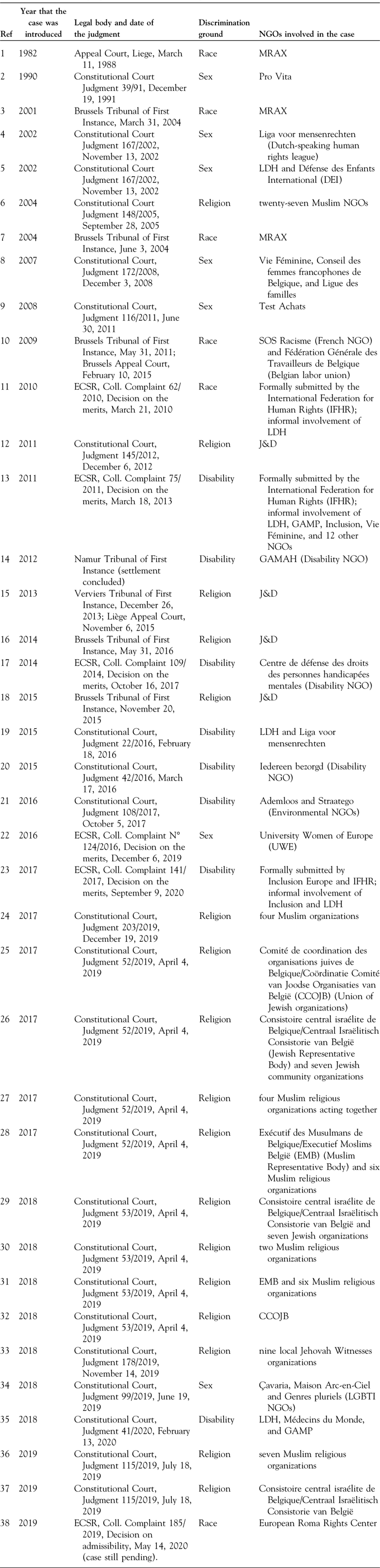

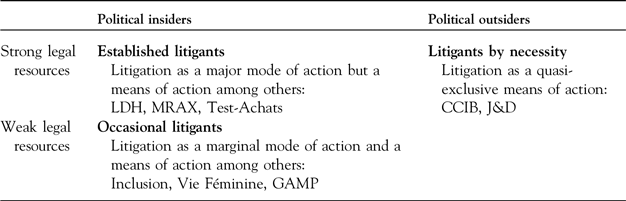

Based on this preliminary research, we selected eight organizations among those that had been involved in at least one legal proceeding relating to discrimination. The selection was made in such a way as to ensure that experience with litigation was represented pertaining to each of the four discrimination grounds with which the research is concerned. Moreover, we chose organizations with varying lengths of existence: given that legal opportunities have evolved over time, this allowed us to compare organizations created at different stages of this evolution (see Table 1).

Table 1. List of NGOs

Some NGOs have a broad mandate allowing them to deal with any discrimination ground. The Ligue des Droits Humains (Human Rights League or LDH) aims to defend all the rights recognized in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.Footnote 11 In practice, it has brought cases relating to all four grounds selected for this research. The Association Belge des Consommateurs Test-Achats/Belgische Verbruikersunie Test-Aankoop (Test-Achats) seeks to advance consumer rights in general. It has lodged complaints on sex discrimination (as well as age discrimination, but this latter ground is outside the scope of this research). Other NGOs, by contrast, are active on issues linked to a single discrimination ground. This group includes Vie Féminine, a feminist organization seeking to promote “a society based on equality, solidarity, and justice”; the Mouvement contre le Racisme, l’Antisémitiste et la Xénophobie (Movement against Racism, Antisemitism, and Xenophobia or MRAX), which combats all forms of racism and defends the rights of aliens; Inclusion, a disability organization advancing the rights and interests of people with intellectual disabilities; and the Groupe d’action contre le manque de places (Group for Action against the Shortage of Places or GAMP), another disability group defending the right of highly dependent people with disabilities to benefit from adequate services and support. The last two NGOs—the Collectif contre l’Islamophobie en Belgique (Group against Islamophobia in Belgium or CCIB) and Justice and Democracy (J&D)—focus on discrimination against one specific group—namely, Muslims. J&D describes itself as an organization devoted to defending justice, democracy, and human rights with a specific focus on antidiscrimination. In practice, however, it has until now been focused on combating discrimination against Muslims, much like the CCIB, which defines itself as an anti-racist, pluralist, and non-confessional NGO devoted to combating Islamophobia.

These NGOs were founded in different time periods. Two of them date back to the early twentieth century: the LDH was founded in 1901 (Morelli Reference Morelli, Schmale and Treiblmayr2017), and Vie Féminine was created in 1920 as a result of the merging of several Christian female workers’ groups (Masquelier Reference Masquelier2019). Three other organizations were established during the postwar era in the 1950s and 1960s: Test-Achats was created in 1957, based on the model of UK and US consumers’ organizations (Van Ryckeghem Reference Van Ryckeghem2005); Inclusion was founded in 1959 by parents of children with intellectual disabilities; the MRAX was founded in 1966, mainly by Jewish leftist activists and former resistance fighters (Hanin Reference Hanin2005). Finally, the last three NGOs were created after 2000, thus after the major evolutions regarding legal opportunities mentioned below had taken place: the disability organization, the GAMP, in 2005, J&D in 2009, and the CCIB in 2014.

Between February and April 2019, we conducted fourteen semi-structured interviews with activists working in these eight NGOs. The interviewees included executive directors or former executive directors, policy officers, and in-house lawyers. We also conducted two interviews with private lawyers who had been involved in some of the cases brought by these NGOs and collective interviews with legal officers from the two Belgian equality agencies. All these interviews were recorded and then transcribed.

THE BELGIAN LEGAL FRAMEWORK: THE PROGRESSIVE EXPANSION OF LEGAL OPPORTUNITIES

The Belgian legal framework was for a long time relatively unfavorable to the use of courts by NGOs seeking to promote legal-political changes. However, the Belgian legal system has undergone dramatic changes due to a combination of factors mentioned below. As a result, the opportunities available to NGOs to resort to litigation have been significantly expanded over time, in particular, in the field of antidiscrimination.

Constitutional Review under Belgian Law

One important factor explaining why legal action is especially attractive for US-based NGOs seeking to promote legal-political change lies with the fact that, under US law, all ordinary courts have the power of judicial review. If a court finds that an executive or legislative Act is inconsistent with constitutional norms, it will deny this Act legal effect in the case at hand. By the application of stare decisis, any court subordinate to it will follow suit (Michelman Reference Michelman, Ginsburg and Dixon2011). If such a conclusion is reached by the Supreme Court, it has the same effect as an abrogation of the Act: the latter will no longer be applied by any court. Although based on a particular case, such a judicial decision has an impact on society as a whole by inducing a transformation of the law.

In Belgium, by contrast, as in many European states, ordinary courts do not have the power to conduct constitutional review of statutes (Verdussen Reference Verdussen2012).Footnote 12 Until the early 1980s, no judicial institution whatsoever was entitled to review the constitutionality of a law. However, the transformation of the country into a federal state prompted the Belgian authorities to establish in 1984 a Constitutional Court. Its task was initially limited to controlling compliance with the rules governing the division of power between the central state and the federated entities. But, in 1988, its powers were extended to the review of statutes’ conformity with the right to equality, the right to non-discrimination, and freedom of education. In 2003, its competences were further extended to the review of compliance with all constitutional fundamental rights provisions (Verdussen Reference Verdussen2012).Footnote 13 Hence, the judicial review of legislation does now exist in Belgium but, unlike in the United States, it is practiced by a specialized court, separate from the rest of the judiciary.

This judicial review takes two forms. First, individuals or organizations “demonstrating an interest” can challenge before this Court any new statute within six months of its enactment. Thus, a NGO willing to obtain the invalidation of a law does not need to find an individual who was personally harmed by it and bring their case to court; it can directly challenge the law itself. If the Court concludes that it contradicts a constitutional norm, it can abrogate the Act. Second, any court that has doubts about the constitutionality of a law applicable to a case before it can petition the Constitutional Court to review the validity of that law. A NGO that is party to a case can thus try to convince the judge to refer a question to this court. If the statute is found to be unconstitutional, it cannot have legal effect in the case that gave rise to the petition, and, within six months of this ruling, its abrogation can be requested from the Constitutional Court.

The Legal Standing of NGOs under Belgian Law

The issue of the legal standing of NGOs in Belgian law is especially complex as different rules exist for ordinary courts and the Constitutional Court respectively, and, moreover, these rules have changed over time. NGOs’ access to ordinary courts was for a long time very limited under Belgian law until the legislation was changed in December 2018. Under classic procedural law, for a legal action to be admissible, the complainant must show that they have “an interest” in the case. The Court of Cassation interpreted this concept restrictively as meaning a “personal and direct interest.” It established in its 1982 Eikendael ruling that, in the case of a legal person, “interest” includes everything pertaining to the organization’s existence, property, honor, and reputation, but it does not cover the objectives that it pursues under its statutes. A legal action brought by a NGO based on its statutory objectives, such as the defense of human rights, was thus considered inadmissible. Nonetheless, some NGOs continuously attempted to bring complaints of this kind in an effort to trigger a change in case law. Some lower courts did consider such complaints admissible in some circumstances, but the Court of Cassation repeatedly quashed these decisions (Romainville and de Stexhe Reference Romainville and de Stexhe2020).

From the 1980s onwards, legal standing was recognized for certain NGOs by specific statutes, notably in the field of antidiscrimination. First, the Antiracism Act adopted in 1981 allowed NGOs that had racial antidiscrimination among their statutory objectives to file complaints based on this law. In 2003, the General Federal Antidiscrimination Act, which transposed the 2000 EU directives on antidiscrimination, extended legal standing to NGOs for cases relating to discrimination based on sex, disability, and religion (among other grounds).Footnote 14 In October 2012, in the context of a case brought by the Défense des enfants International Belgique, a children’s rights NGO, the Brussels Labor Tribunal decided to refer to the Constitutional Court a question about the inequality existing between NGOs wishing to bring a legal action in relation to human rights, given that, depending on the kind of rights at stake, some could rely on a specific statute conferring them legal standing while others could not. The Constitutional Court answered that this difference was indeed in breach of the constitutional equality and non-discrimination guarantees, and it invited legislators to remedy this situation.Footnote 15 Following further legal actions brought by several NGOs, an amendment to the procedural law was finally passed in 2018 (Romainville and de Stexhe Reference Romainville and de Stexhe2020). As a result of this amendment, any legal person whose statutory goals includes the protection of rights and freedoms is now authorized to file a case with a view to protecting human rights or fundamental freedoms recognized by the Constitution or by international instruments binding upon Belgium. This strikingly illustrates how NGOs may develop judicial strategies aimed at expanding the legal opportunities available to them in the country in which they operate.

By contrast with ordinary courts, a NGO’s access to the Constitutional Court has been much easier. Initially, the right to petition this court to request the abrogation of a law was limited to legally designated public authorities. But, in 1988, when the court’s powers were extended to the review of certain constitutional rights, access to it was enlarged to “any person demonstrating an interest.” Unlike the Court of Cassation, the Constitutional Court adopted a generous interpretation of this concept: it accepted that legal persons, including NGOs, had an interest in challenging a statute likely to affect their statutory goals (Verdussen Reference Verdussen, Born and Jongen2015).

Opportunities for Legal Mobilization Offered by European (Quasi-)judicial Institutions

The participation of Belgium in European judicial or quasi-judicial systems offers additional opportunities for legal mobilization to NGOs. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which controls compliance with EU law by EU member states and EU institutions, and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which monitors the European Convention on Human Rights,Footnote 16 are the oldest and most prominent examples of European judicial bodies. These two courts, however, are not easily accessible to NGOs. Direct access to the ECtHR is limited to individuals or organizations claiming to be personally the victims of a rights violation. In principle, this excludes applications by NGOs motivated by the pursuit of their statutory goals. A NGO, however, may be authorized by the president of the court to intervene as a third party in a case (the equivalent of amicus curiae in the United States) or formally designated by an applicant as its representative before the Court (Cichowski Reference Cichowski2007; Van den Eynde Reference Van den Eynde2018). As for the CJEU, it is mainly accessed indirectly through requests submitted by national courts seeking clarifications of the interpretation of EU law provisions (which are called requests for preliminary rulings) in the context of a case before them. Direct access to the CJEU for legal persons is possible only against legislative and (certain) regulatory acts of the EU and under very strict conditions that, in practice, exclude proceedings for NGOs based on their statutory objectives.Footnote 17

Although less well known, the European Committee of Social Rights offers better prospects for NGOs seeking to engage in legal action against discrimination. This committee oversees the implementation of the European Social Charter, a treaty laying down social and economic rights, including the right not to be discriminated against.Footnote 18 The 1995 additional protocol to this charter, ratified by Belgium in 2003, entitles NGOs to submit so-called “collective complaints” against a state party to the committee with a view to having a breach of the European Social Charter recognized.Footnote 19 The peculiarity of this “collective complaint” procedure is that it can be initiated only by NGOs, labor unions, and employer organizations. In principle, the concerned NGOs are (mainly) international NGOs included in a list established for this purpose. In practice, however, it frequently occurs that local NGOs wishing to bring a complaint come to an arrangement with one of the officially listed NGOs: the complaint is prepared by the former but formally lodged by the latter. Importantly, these “collective complaints” cannot concern individual situations, but they may only serve to challenge a state’s law or practice allegedly in breach of one or more provisions of the charter. Furthermore, unlike applicants before the ECtHR, the complaining organization does not need to exhaust domestic remedies before applying to the committee, which facilitates and speeds up access to this European body.

The European Committee of Social Rights is not officially recognized as a court because, contrary to the ECtHR or the CJEU, its decisions are not, strictly speaking, legally binding. Yet it is empowered to provide an authoritative interpretation of the European Social Charter, and proceedings before it are similar to a court procedure: both parties present their arguments, the committee decides first on the admissibility and then on the merits of the case, and its decisions are based on a legal reasoning. It is thus characterized as a “quasi-judicial body.” Importantly, our interviews show that activists who bring complaints before this committee see this as a form of litigation.

THE DIFFERENTIAL USE OF LITIGATION BY NGOs: EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

We now move to our exploration of the use of litigation by Belgium-based NGOs in relation to discrimination. While our quantitative data show a clear increase of such legal actions over time, our qualitative inquiry, focused on the sample of NGOs selected for this study, allows us to highlight factors that explain not only why they go to court but also why some do so more intensely than others. Based on our major findings, we build a typology of NGOs that reflect their different modes of relating to litigation.

Quantifying Belgium-based NGOs’ Legal Activism against Discrimination

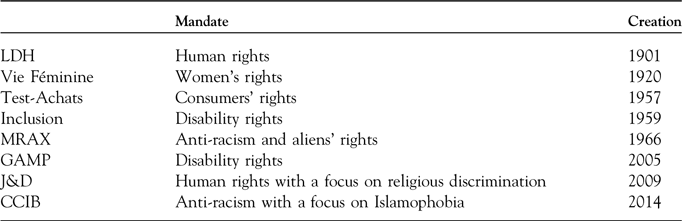

Here, we assess the extent to which litigation is used by Belgium-based organizations to combat discrimination. To this end, we consider the number of cases initiated by NGOs before three kinds of legal bodies: ordinary courts, the Constitutional Court, and the European Committee of Social Rights. Our investigation indicates that, in all three categories of legal bodies considered, there has been a clear rise over time in the number of legal actions brought by NGOs. In the context of ordinary courts, NGOs have been authorized to bring actions in relation to race/ethnic origin discrimination since 1981 based on the Antiracism Act. However, as noted earlier, it was only in 2003 that the first General Federal Antidiscrimination Act was adopted, which allowed NGOs to act against sex, disability, or religious discrimination. Moreover, the 2003 Act enlarged the scope for action against race/ethnic origin discrimination, by adding the possibility of a civil lawsuit to that of bringing a criminal complaint. Overall, NGOs have used the opportunities offered by the antidiscrimination statutes parsimoniously to challenge discrimination based on the four selected grounds: between 1981 and 2019, we identified only eight relevant cases initiated by a non-profit organization. However, the figures increase over time: whereas, among the cases we found, only one occurred between 1980 and 1989 and none between 1990 and 1999, three were submitted between 2000 and 2009 and four between 2010 and 2019. The rise in cases clearly correlates with the enlargement of legal opportunities from 2003 onwards (Figure 1 and Appendix 1).

Figure 1. Legal actions challenging discrimination based on race/ethnic origin, religion, gender, or disability, initiated by Belgium-based NGOs between 1980 and 2019 (by year of introduction of the action, ground of discrimination, and type of institution). Source: data collected by the authors.

If we turn to the Constitutional Court, the gradual growth of NGOs’ activism in relation to race/ethnic origin, sex, religion, or disability discrimination is even more striking. Only one relevant case could be found in the period between 1980 and 1989 as well as in the following period between 1990 and 1999. But, between 2000 and 2009, the number of applications corresponding to our criteria rises to four, and, between 2010 and 2019, it increases to eighteen. As for the European Committee of Social Rights, which has been open to collective complaints against Belgium since 2003, it received six applications corresponding to our criteria in the time period considered: one between 2000 and 2009 and five between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 1 and Appendix 1).

Overall, confirming what has been observed in the literature, our investigation shows that, when new legal opportunities become available for NGOs defending a public interest, they are more likely to use the legal system (De Fazio Reference De Fazio2012). In the Belgian context, the period considered is marked by several turning points: the adoption of new statutes providing NGOs with legal standing in the field of discrimination (in particular, in 1981 and 2003); the creation of the Constitutional Court and the recognition of NGOs’ legal standing before it (in 1988); and the acceptance by the state of a new international remedy open to NGOs (in 2003). However, the enlargement of legal opportunities is not sufficient to explain why NGOs turn to litigation. Indeed, these legal opportunities are not used by all NGOs situated in Belgium. Furthermore, among organizations that bring lawsuits, some do so much more often than others. If we consider the fifteen legal actions initiated by NGOs in our sample in relation to discrimination based on one of our four criteria, we observe that the LDH took a leading role in six of them; the MRAX in three of them, while Inclusion and the GAMP submitted only one complaint (see Appendix 1). Actually, if we take into account all of the cases submitted by NGOs to the Constitutional Court, and not merely the cases relating to discrimination based on our four criteria (which represent only a small portion of applications before it), the disparity between organizations as to their propensity to apply is even more remarkable. Between 1988 and 2019, the LDH submitted seventy-nine applications before this court alleging the violation of various constitutionally protected rights, while the GAMP, for instance, was involved in only one case. In order to understand these differences between NGOs, in the next two sections, we investigate the process through which our sample of organizations came to use litigation and the extent to which this form of activism was integrated in their tactical repertoire.

The Impact of the Insider/Outsider Position in the Use of Litigation

All NGO activists interviewed share the view that litigation is a measure of last resort, which they turn to when other means of action are ineffective. Yet we observed an important difference among the organizations studied with respect to the moment in which they started to use legal proceedings: for some of them, legal action was not originally a means of action but became so at a certain point in their history; for others, it was a central strategy from the start. Noticeably, this distinction coincides with their respective position in the political field: NGOs in the first category all appear as insiders, whereas organizations of the second type can be characterized as outsiders. This insider/outsider cleavage also corresponds to a different perception of the political environment: while the former perceive it as mixed or fluctuating, meaning that it is sometimes favorable to the causes they defend and sometimes not, depending on the political parties in power or the subject matter at stake, the latter see this environment as consistently hostile to their objectives.

The Political Insiders

Most NGOs in our sample—the LDH, the MRAX, Test-Achats, Vie Féminine, Inclusion, and the GAMP—did not originally use litigation to pursue their goals. They developed diverse types of activities, with variations depending on the organization. But all of them have engaged in particular in political lobbying and participation in policy-making processes. They have all been recognized as legitimate interlocutors by political actors and integrated in formal processes of consultation. They have taken part regularly in institutional advisory bodies or parliamentary hearings. They can be described as political insiders. At some point in their history, however, they felt that their established means of action were not—or no longer—sufficiently effective. This prompted them to turn to legal action. As several interviewees told us, legal action in some circumstances appeared to them as “the only possibility to get heard.”

For the LDH, the MRAX, and Test-Achats, the shift toward litigation occurred in the 1980s and 1990s. The circumstances of this transformation vary. LDH activists make a clear link between their decision to engage heavily in litigation tactics in the late 1990s and what they see as the declining effectiveness of political lobbying. While this organization had always been led by lawyers, legal action was not among its usual means of action before this period. Rather, its preferred mode of intervention was to produce reports on human rights violations and to press for legislative reforms through media interventions and lobbying with officials (Dieu Reference Dieu1999). Activists feel that for a long time their organization was able to exert a strong political influence thanks to its close contacts with members of parliament and parliamentary assistants but that this changed in the course of the 1990s: decision-making power increasingly moved away from legislators to the executive and political parties, resulting in a declining capacity of the LDH to influence laws and policies. The organization thus started to experiment with litigation, which, in its view, proved much more effective than political lobbying. Hence, it progressively became one of its central means of action. A legal officer, who has been working for the LDH for more than fifteen years, describes this trend: “Since I’ve been here, we’ve been going less and less before parliamentary assemblies because we’ve noticed that these processes are inefficient; they’re very time-consuming with very few, if any, results; hence, we’re going more and more to court to try to make our viewpoint heard … and we’ve had quite a lot of success in this” (Interview 1). The organization has therefore increasingly developed litigation tactics and was encouraged to do so by significant judicial victories.

For the MRAX, the turn to legal action dates back to 1981 when the Antiracism Act was passed: as soon as this law was adopted, the organization decided to use this new means of action. This move occurred in a political context that was increasingly hostile to the claims made by antiracist movements. In Belgium, the 1980s were marked by a rise in xenophobic rhetoric from locally elected political figures. Against this background, the organization viewed legal action as a way to both delegitimize racist attitudes by bringing these politicians to court and to use the court proceedings as a platform with which to amplify their political message (Hanin Reference Hanin2005).

Test-Achats also started to develop litigation strategies in the course of the 1980s (Van Ryckeghem Reference Van Ryckeghem2005). From the mid-1990s, it brought increasing numbers of legal actions in the field of insurance. This culminated in a case brought before the Constitutional Court against the 2007 Gender Antidiscrimination Act,Footnote 20 alleging that the continuing existence of a derogation in the field of insurance was in breach of the prohibition of sex discrimination. The organization managed to convince the court to refer a question to the CJEU.Footnote 21 According to the former director of the insurance department of Test-Achats, the extensive use of litigation in the field of insurance is due to the fact that political means of action are ineffective in this domain because insurance companies constitute a “very effective and powerful lobby” (Interview 9). Although the organization is consulted during the legislative process at both national and European levels, Test-Achats activists believe that state authorities are much more receptive to companies’ claims than to their viewpoint. Hence, legal action, especially before the Constitutional Court, is viewed as a powerful means of action for challenging a law adopted without taking into account their demands.

Vie Féminine, Inclusion, and the GAMP turned to litigation for the first time more recently; in 2007, for Vie Féminine and, in 2011, for Inclusion and the GAMP. For Vie Féminine, the first experience of going to court followed its failure to influence the new divorce law adopted in 2007. From the time when it started to engage in political lobbying in the 1970s, reforms in the domain of family law usually bore its imprint (Masquelier Reference Masquelier2019). This time too, it had been very active during the legislative process; it had contacts with legislators and was heard by the Parliament. And, yet, when the bill was voted on, the activists felt that their arguments had been totally ignored: “This was a difficult moment because we realized that ultimately even those who’d been receptive to our arguments didn’t say anything. … And then, what we did when coming out of there was to say: ‘But what can we do?’ So we re-activated the links we’d had with some lawyers. … And they told us: ‘The only leverage that remains is to initiate a legal action against this law’” (Interview 7).

Vie Féminine followed their advice and applied to the Constitutional Court.Footnote 22 The GAMP and Inclusion first experimented with legal action when taking part in the collective complaint submitted to the European Committee of Social Rights in 2011 to challenge the lack of institutional solutions for highly dependent disabled persons.Footnote 23 The initiative came from the GAMP. Created in 2005, it had engaged in political lobbying, communication campaigns, and protest actions. After a few years of existence, having concluded that these means of action had produced some results but not sufficient ones, the GAMP’s activists started to reflect upon trying other modes of intervention. They saw legal action as a way “to force the state to act” (Interview 8). They took advice from human rights lawyers, who suggested the collective complaint mechanism.Footnote 24 A few years later, in 2017, Inclusion initiated another collective complaint to challenge the exclusion of children with disabilities from mainstream schools.Footnote 25 Here too, the activists had first resorted to political lobbying, but they came to the conclusion that officials were totally impervious to their perspective. Some members of the organization therefore suggested that they try legal action and the organization accepted.

Importantly, all these insider organizations have continued to resort in parallel to other modes of action. Litigation has not replaced their previous forms of intervention; rather, it has complemented their tactical repertoire. Commenting on the connections between litigation and political action, one member of the LDH explained: “They can combine because sometimes, on political issues, legal action can help, … it allows one to attract media attention, it allows one to put pressure on political actors, all this is linked. And thus, depending on the issue and timing, we may put the emphasis on either type of action and they finally reinforce each other” (Interview 5). For these organizations, legal action currently represents one form of intervention among others, complementing their other modes of action.

The Political Outsiders

Contrary to the NGOs examined so far, J&D and the CCIB have decided from the start that legal action was going to be their central mode of intervention. They have engaged little, if at all, in political lobbying and consultation processes. Rather, they have adopted a position of being an outsider in the political realm. While their position as an outsider appears as the result of a choice, it is a choice made against the background of hostile circumstances. Both organizations focus on combating discrimination against Muslims and, in particular, Muslim women wearing headscarves. Their founders consider that they have always faced a political elite that was unsympathetic to their claim. In the last thirty years, Belgium has been marked by acute controversies over the visibility of Islam in the public space and the wearing of religious symbols in various settings (Coene and Longman Reference Coene and Longman2008). Headscarf bans decided by schools, higher education institutions, local administrations, or private employers have multiplied. Given the sensitivity of the issue, and the negative perception of the headscarf among a large part of the population, the political elite is very reluctant to support challenges to these bans (Ringelheim Reference Ringelheim2012).

In this context, J&D and the CCIB anticipated that they would be unable to influence the political process through lobbying or advisory mechanisms. Hence, they chose to focus their efforts on a means of action that is external to political institutions. They see law and the judiciary as providing the opportunity to make a principled position prevail over political attitudes dominated by partisan interests: “[The judiciary is] the only barrier that still exists in a constitutional state when politicians have abandoned their missions” (Interview 11). “[Going to court] allows us to give priority to legal concerns over political concerns. … [And when we win the case], it makes it possible to reverse the power relation a little” (Interview 4). Litigation appears to them as their best option for pursuing their objectives and gaining some victories in a political environment that they perceive as very unfavorable to their cause.

The specificity of the cause defended by an organization thus has an impact on its choice of a means of action. Contesting religious discrimination, and especially bans on the wearing of religious symbols, appears to generate a higher level of opposition in the Belgian political environment than challenging sex, race/ethnic, and disability discrimination. This does not mean that organizations engaged in combating these three latter forms of discrimination do not face resistance in political arenas, but, as the interviews suggest, they are able to find some degree of support from at least some political actors. Whereas these insider organizations use other means of action in parallel to litigation, organizations occupying the position of outsiders tend to use dispute resolution and lawsuits as their quasi-exclusive strategies in efforts to promote social and policy changes.Footnote 26 Moreover, while the former have turned to litigation years after they were created, the latter did so from the start.

Importantly, J&D and the CCIB were both founded after 2003, thus after the major reforms that opened the possibilities for NGO-led litigation against discrimination had been passed. The state of the law at the time of their creation certainly had an influence on the tactical choice they made. However, the example of the GAMP shows that this factor was not determining: the GAMP was created in 2005, yet, contrary to J&D and the CCIB, it did not use litigation at the beginning; it only started to do so after some years of existence and continues today to resort to others means of action.

Legal Resources

Another important difference among the organizations studied concerns the place of litigation in their tactical repertoire: for some, it has become—or was from the start—a major mode of action. For others, it remains a marginal experience that differs from their common practices. Based on our interviews and our research into the history of the selected NGOs, we find that this disparity correlates with a difference in legal resources. We observe that the strength of each organization’s legal resources impacts on their propensity to use existing legal opportunities. This shows that the mere existence of legal opportunities in the environment is not sufficient for an organization to use them. A NGO needs to have a certain degree of legal expertise to be aware of the availability of such opportunities and to know how to use them. NGOs with weak legal resources, by contrast, have little knowledge of the legal system and depend on the support of external actors—such as other NGOs or occasional contact with a lawyer who is willing to help—to be able to initiate a legal action. This distinction does not coincide with the insider/outsider division: among organizations with strong legal resources, we find both insiders and outsiders, while those with weak legal resources include only insiders. This observation raises a further question: why do some NGOs develop strong legal resources, while others do not? And does their position as an insider or outsider play a role in this process?

Strong Legal Resources

Among the organizations that have made of legal proceedings a major means of action, we find some political insiders (the LDH, Test-Achats, and the MRAX) and the two political outsiders (J&D and the CCIB). All of them have in common the fact that they have strong legal resources. Yet they differ as to when they acquired this legal capacity: the former three NGOs had developed legal resources before they first went to court, whereas the latter two forged their legal capacity after deciding to make litigation a central mode of intervention. Founded by lawyers in 1901, the LDH has always attracted practicing lawyers among its members and leaders (Dieu Reference Dieu1999; Morelli Reference Morelli, Schmale and Treiblmayr2017). Test-Achats created strong links with lawyers early on in its history: during the 1970s, it created a journal specialized in providing legal advice to consumers, and, in 1979, it started to collaborate with a university research center specializing in consumer protection law (Van Ryckeghem Reference Van Ryckeghem2005). The MRAX began to work with lawyers in the 1960s and 1970s when it engaged in legislative advocacy on aliens’ rights and anti-racism. In 1980, it hired its first lawyer in order to provide free legal assistance to migrant workers. In 1981, when the Antiracism Act was passed, it used the contacts it had already established with practicing lawyers to set up a legal commission to help it make use of this law (Hanin Reference Hanin2005).

Thus, when these organizations contemplated turning to litigation in response to the perceived lack of effectiveness of political action, they already had resources in place that allowed them to accomplish this ambition. The move toward the use of legal action was relatively straightforward. Subsequently, litigation progressively became one of their major modes of operation leading them to develop their legal resources even further. In 2019, Test-Achats had thirty lawyers among its 380 employees. The LDH and the MRAX both employed two legal officers out of their teams of—fourteen and thirteen members respectively. In addition, these three organizations had close connections with external legal counsel, with expertise in fields of interest to them. The LDH, in particular, has created a network of lawyers willing to work pro bono or at a low fee on the legal actions that the organization takes.

J&D and the CCIB, our two political outsiders, have also developed strong legal resources, although to a lesser extent than the three organizations discussed above. The sequence of events, however, was different. Both organizations were determined from the start to resort to legal action, and they have therefore undertaken to acquire the legal resources they needed to implement this strategy. This is all the more remarkable as these two organizations are much smaller and have more limited material means than Test-Achats, the LDH, or the MRAX. J&D is run exclusively by volunteers, but it works with a small group of “resource persons” who support its action, which includes practicing lawyers. When they go to court, they usually call on a member of this network, who is willing to work for a low fee, unless they need specific expertise. Additionally, the three directors of the organization (one of whom has a legal background) have themselves developed an expertise in antidiscrimination law. When they engage in a lawsuit, they actively participate in the preparation of the case. As for the CCIB, it has only one employee, who works part-time and has no background in law. Since its legal actions are focused on bans on the wearing of headscarves in higher education institutions, it has developed a close relationship with a law firm specializing in education law. It has also created links with other, more established, actors in the field of antidiscrimination—in particular, the Belgian equality agency Unia and the LDH—and has collaborated with them on certain cases. NGOs with limited material resources may thus be able to acquire a relatively strong legal capacity (Aspinwall Reference Aspinwall2021).

Weak Legal Resources

Activists from the three other NGOs—Vie Féminine, Inclusion, and the GAMP—presented their organization in interviews as being poorly endowed with legal skills. None of them has an in-house lawyer. Going to court appears to them as a difficult enterprise that is not part of their usual activities. Despite having already experienced litigation, they do not have a clear idea of existing legal opportunities. Interviewees from the GAMP and Inclusion explained that they learned in a circumstantial way about the possibility of applying to the European Committee of Social Rights. Activists from the GAMP acquired this awareness through one of their members, the father of a severely disabled child, who was a practicing lawyer and a member of the LDH.Footnote 27 He put them in contact with a colleague specialized in human rights law, who was herself a member of the LDH’s board of directors. She suggested submitting a collective complaint to the European Committee of Social Rights and agreed to work on the case for a reduced fee. The story of Inclusion is very similar: they had among their members the sister of a prominent human rights law scholar. He informed his sister about the possibility of petitioning the European Committee of Social Rights. He also helped with the case and put them in contact with the LDH and the lawyer who had previously worked on the complaint initiated by the GAMP.

While these NGOs have all been involved in two (the GAMP and Inclusion) or three (Vie feminine) cases, each of them actually initiated a case only once; on the other occasions, they were invited to join an action that had been initiated by others. Although these activists view legal actions as important moments in their collective history, they do not consider them as a turning point that transformed their repertoires of action, despite the fact that all of these cases but one were successful. When asked if they would be willing to go to court again in the future, they do not rule it out but are unsure about their organization’s capacity to do so and the legal avenues available to them. The project manager from Inclusion stressed that the access to legal resources that allowed them to engage in a collective complaint was exceptional and highly dependent on the human rights law scholar who assisted them: “The International Federation for Human Rights had already brought the collective complaint on highly dependent disabled people before the European Committee of Social Rights, and I think that the legal expert knew them, so the connection was easy. … We were lucky to benefit from [his] expertise” (Interview 6).

On closer inspection, however, it appears that Vie Féminine and Inclusion are not totally lacking in legal resources. Inclusion previously had a lawyer among its personnel, but her tasks were limited to providing advice to members of the organization. At the time of the interview, she had left the organization and had not been replaced. At one point in its history, Inclusion had also set up a legal commission composed of judges, practicing lawyers, and others to help it work on a specific piece of legislation, but this initiative has since been discontinued. As for Vie Féminine, in some of its regional sections, it organizes a legal assistance service specialized in family law and migrant women’s rights, but this service is limited to a few hours per month. The organization has also developed connections with lawyers who occasionally help it to define its position on certain legal reforms. We might therefore ask why these organizations have not attempted to use their contacts with legal experts to develop stronger legal resources oriented toward litigation, as J&D and the CCIB did.

Two factors may explain this attitude. The first relates to the fact that Inclusion and Vie Féminine, which are political insiders, do not perceive the political environment as always being unfavorable to them. Both organizations are part of official advisory bodies and have regular contacts with political actors. They sometimes manage to obtain results through these channels. Hence, they may lack a sufficient incentive to profoundly transform their modes of operation and redirect their forces, currently focused on the provision of services to their members and political lobbying, toward acquiring strong legal skills. But this raises the question as to why Test-Achats, the LDH, and the MRAX, which are also political insiders, did choose to make of litigation a major mode of action.

A second factor may explain this difference. It has to do with the organizations’ collective identity. Inclusion and Vie Féminine both see themselves as grassroots organizations whose missions consist primarily in responding to the demands and needs of their members through a bottom-up approach. The former president of Vie Féminine insists that its organization is “a community education movement that works with women from unprivileged backgrounds.” She observes that “[legal action] remains something that isn’t obvious for us because our movement doesn’t have this tradition” (Interview 7). This suggests that legal action is seen within this organization as an unsuitable strategy to fit with the NGO’s self-image and overall modes of operation. By contrast, Test-Achats, the LDH, and the MRAX have developed a close familiarity with the law and legal discourse even before resorting to litigation: the acquisition of legal resources has gone hand in hand with collaboration with lawyers and a tendency to frame their claims in legal terms. Hence, the decision to use litigation and to make of it a central tactic was in phase with their organizational identity.

The situation of Inclusion and Vie Féminine can also be contrasted with that of J&D and the CCIB, the two NGOs devoted to combating discrimination against Muslims: confronted with a political environment that they perceived as unchangingly hostile, they positioned themselves as political outsiders and chose to concentrate most of their limited means on building a capacity to go to court. Interestingly, the experience of J&D and the CCIB also shows that prior possession of legal resources is not a necessary condition for an organization to decide to make of litigation a major mode of action: in their case, the acquisition of legal resources derived from their willingness to rely on legal action to achieve their goals.

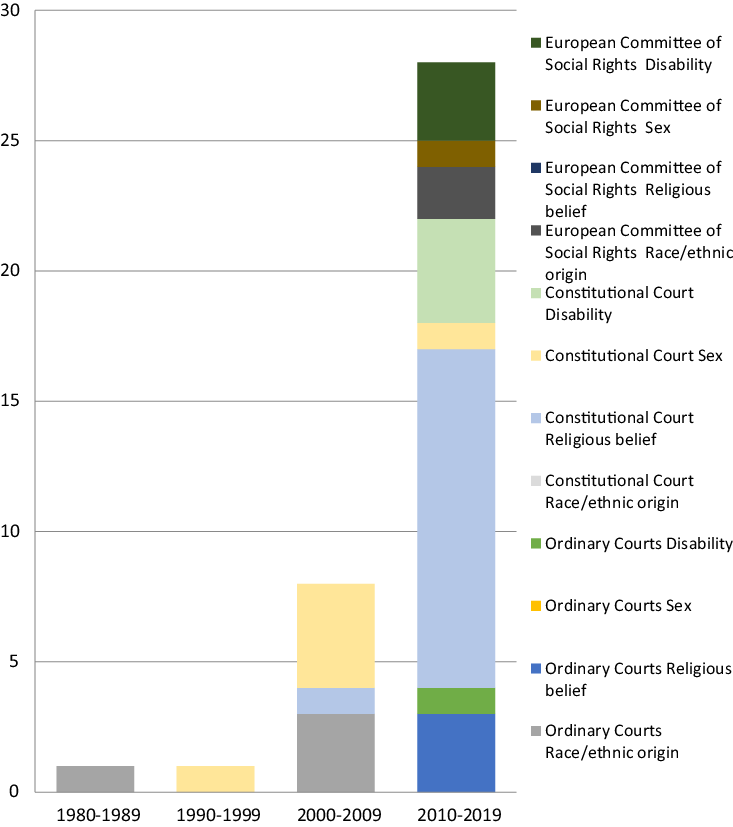

The Differential Use of Litigation by NGOs: A Typology

Based on the two dimensions analyzed in the previous sections—their position as political insider or outsider and the legal resources available to them—three types of NGOs can be distinguished. The first group is composed of organizations that are political insiders and that have strong legal resources. These NGOs use courts frequently while also resorting to other means of action—in particular, political means. We call them the “established litigants.” They are “established” in two senses: they have a robust experience of litigation, and they are recognized by policy makers as legitimate interlocutors. The second category gathers NGOs that also hold a position of political insider but have weak legal resources. Their use of legal action remains rare; other forms of intervention, including lobbying and participation in consultation processes, remain their privileged modes of operation. We label them the “occasional litigants.” The third and last group includes NGOs that remain political outsiders but have developed relatively strong legal resources. Confronted with a political environment that they perceive as hostile to their cause, these NGOs have used litigation regularly from the start in preference to political means of action. We designate them as “litigants by necessity.”

Table 2 presents these three categories. There is no NGO in the last box as none of the NGOs in our sample can be characterized as combining both an outsider status and the possession of weak legal resources. Although this should be verified through other case studies, we make the hypothesis that NGOs in this situation do not use the legal system: they would need to develop strong legal resources to compensate for their weak political position. The following section highlights in greater detail the differences in the way these three groups of NGOs use litigation to pursue their public’s rights.

Table 2. Typology of NGOs

Source: Analysis by the authors, based on interviews with activists, NGOs’ archives, and our case law database.

The Established Litigants

The “established litigants” are well-established organizations that have existed for several decades. They have strong legal resources and have been using litigation regularly for at least twenty years. Legal action is “embedded” in their activities (Vanhala Reference Vanhala2018, 389). Members of these organizations see it as an important component of their tactical repertoire. At the same time, they have a position of political insiders and are thus actively involved in political lobbying and consultation mechanisms. In our sample, three organizations can be characterized as established litigants: the LDH, Test-Achats, and the MRAX. The intensity of the LDH’s litigation activity is especially notable. Between 2000 and 2019, it initiated six cases relating to sex, racial/ethnic, religious, or disability discrimination: three collective complaints to the European Committee of Social RightsFootnote 28 and three applications before the Constitutional Court.Footnote 29 The LDH is actually the only organization that has been involved in cases relating to all four discrimination criteria selected in our research. Lawsuits relating to these forms of discrimination, however, represent only a small portion of the litigation practice of this organization, whose mandate extends to the defense of all human rights. If we consider all of the cases initiated by the LDH during this period, we arrive at 132 proceedings in total.Footnote 30 Moreover, it has filed ten voluntary interventions in cases brought by others, including in discrimination cases.Footnote 31

The established litigants can be compared to the “repeat players” identified by Marc Galanter (Reference Galanter1974, 97), insofar as they “are engaged in many similar litigations over time.” Their practice of litigation is routinized. Through their repeated use of the courts, they have developed a close knowledge of the legal system, which makes them experts in the handling of litigation. These organizations are thus well informed of the characteristics of their legal environment. They are also well aware of the main limitations and potential of litigation tactics. Thanks to their expertise, they are able to develop sophisticated legal strategies. Furthermore, they do not only use existing legal opportunities but sometimes also strive to expand them. The MRAX and the LDH mobilized strongly in favor of the passing of the 1981 Antiracism Act, including the provision of legal standing to NGOs. Test-Achats lobbied for the creation of a class action in Belgian law in the field of consumers’ rights. More recently, the LDH was among the NGOs that actively contributed to triggering a change in the rules on NGOs’ legal standing by bringing repeated cases raising this issue.

Besides litigation, however, these organizations also use other means of action—in particular, political lobbying and participation in consultative mechanisms. They see their political environment as mixed in terms of receptivity toward their claims, and they continue to strive to advance their objectives through political means while also using lawsuits.

The Occasional Litigants

The “occasional litigants” also hold a position as an insider in the political field. They only recently turned to litigation for the first time and have so far been involved in a very limited number of legal cases. This group includes the two disability organizations Inclusion and the GAMP as well as the feminist organization Vie Féminine. Inclusion has taken part in two collective complaints brought before the European Committee of Social Rights;Footnote 32 the GAMP has participated in one collective complaint and one application before the Constitutional Court;Footnote 33 while Vie Féminine was involved in one case relating to sex discrimination before the Constitutional Court and one collective complaint before the European Committee of Social Rights.Footnote 34 These actions are all relatively recent, with the oldest one dating from 2007.

By contrast with the established litigants, the occasional litigants have weak legal resources. They do not have any in-house lawyers. When they used the judicial system, they relied on external legal experts, with which they had only ad hoc contacts or were invited to join a legal action initiated by other NGOs. Activists from these organizations perceive the legal system as relatively inaccessible. They consider the use of litigation as a marginal part of their activities and as an exceptional deviation from their normal course of action. The bulk of their activities consist in other types of intervention: lobbying, participation in institutional consultative mechanisms, services to their members, or protest actions. Like the “established” organizations, they perceive the attitude of political elites toward their claims as fluctuating. Although, on occasion, they have decided to engage in a legal action after concluding that political strategies had proven to be ineffective on a given issue, they still consider that they can have some degree of influence on decision making through political means.

Litigants by Necessity