The study of women/gender and politicsFootnote 1 within political science grew out of the women’s movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Rapid growth of the subfield continued throughout the 1980s, along with the development of women’s studies courses and programs. Early scholarship on women and politics delineated women’s exclusion from politics and often focused on descriptive analysis of the number of women who vote and run for or hold political office; the second stage of the then-current research analyzed women using existing political frameworks (Randall Reference Randall, Marsh and Stoker2010; Ritter Reference Ritter2007). The current stage engages more fundamental questions about the ways in which political science narrowly defines politics and fails to recognize how gender is ingrained in political processes and institutions. The content of women/gender and politics courses have followed this trajectory as well.

All political scientists have benefited from this expansion of disciplinary boundaries by raising questions about what to study and how to study it. By considering “woman” as a category of study, “feminist political scientists have been able to call into question some of the central assumptions and frameworks of the discipline” (Carroll and Zerilli Reference Carroll, Zerilli and Finifter1993). Clearly, the discipline of political science “now has gender on its agenda” (Bourque Reference Bourque, Freeman, Bourque and Shelton2001). Yet, more recently, discussions among some political scientists have shown that challenges still exist when it comes to incorporating the study of women/gender into the undergraduate curriculum. This article analyzes the current state of how this course it taught, how it fits within the political science undergraduate curriculum, and the challenges that exist for current instructors. Specifically, we are interested in how institutions prioritize this course in the curriculum and whether faculty who teach this topic face resistance from colleagues, administrators, and/or students.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Women/gender and politics is perceived as a legitimate and (sometimes) necessary course of study within political science, and undergraduate courses on the subject have become a common part of the political science curriculum. In most cases, women/gender and politics courses are taught as upper-level, small “boutique” courses that fulfill an elective within the political science major. However, instructors have noted that challenges exist in teaching these courses and in incorporating gender more broadly into the undergraduate curriculum (Krook Reference Krook2009; Lee Reference Lee1993). In short, the situation is “far from ideal” (Tolleson-Rinehart and Carroll Reference Tolleson-Rinehart and Carroll2006).

Scholars have written about the need to “mainstream” the topic of gender within the liberal arts curriculum by integrating it into required core courses. As early as 1991, an American Political Science Association (APSA) report recommended gender mainstreaming as part of a larger effort to diversify the political science curriculum so that gender, ethnicity, and cultural diversity would not be “treated as a separate and unique problem to be dealt with in a particular course or two or by a particular faculty member” (Wahlke Reference Wahlke1991, 53). A more recent analysis, however, shows that the inclusion of gender within political science “has not emerged as a serious priority for curricular reform” despite evidence that gender inclusiveness can have “real and long-term effects on the representation of women in politics and political science departments” (Cassese, Bos, and Duncan Reference Cassese, Bos and Duncan2012). Efforts to mainstream the topic (e.g., offering a lower-level women/gender and politics course) requires instructors to “sell” the topic to students as counter resistance to the idea that gender is worth studying in political science. Mainstreaming is optimal because it “can send a signal that this is an important element of the discipline” (Holman Reference Holman2012). Some have suggested that the continued resistance to adding topics and courses related to women and gender to the political science curriculum is due to skepticism that still exists about the importance of feminist scholarship (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2006). Evidence of this bias is evident in that women/gender and politics is not a well-represented topic in introductory American government textbooks (Atchison Reference Atchison2017; Cassese and Bos Reference Cassese and Bos2013).

Another potential cause of resistance to women/gender in political science is the marginalization of female professors, especially women of color, who serve as the primary instructors of these courses.

Another potential cause of resistance to women/gender in political science is the marginalization of female professors, especially women of color, who serve as the primary instructors of these courses. Women still comprise only 30% of political science faculty nationwide, are paid less than their male colleagues, and hold more nontenure track positions (APSA 2011). Women of color are especially underrepresented in the profession and have made few gains in recent decades. The percentage of black women in political science rose from 4.3% to 6.1% from 1980 to 2010, whereas Latinx women saw an increase from 2.3% to 3.0% (APSA 2011). Alexander-Floyd (Reference Alexander-Floyd2015) found that white women and women of color are seen as outsiders and “invaders” when they enter institutions dominated by white men. Furthermore, women of color face discrimination in hiring, tenure, and promotion processes and aggression from administrators, other faculty, and students (Gutiérrez y Muhs et al. Reference Gutiérrez y Muhs, Niemann, González and Harris2012). Sampaio (Reference Sampaio2006) noted that the “publish or perish” culture in higher education disproportionately affects women of color in political science who have greater demands on their time from teaching and service. They also face challenges by being hired to teach contentious subjects that result in lower teaching evaluations, less favorable promotion evaluations, and a lower likelihood of gaining tenure. The continued marginalization of all women in political science parallels the relegation of women/gender and politics courses to the margins.

Hawkesworth (2016, 17) attributed a “lack of attention to race, gender, and sexuality” in a field “that claims power as a central analytical concept” to the methodological and epistemic practices of mainstream political science. Specifically, she concluded the ways in which political science defines “power” and “the political” serve to obscure state practices that maintain hierarchy. Furthermore, gender and race biases intersect in terms of who is considered a legitimate producer of knowledge in political science in ways that obfuscate the study of hierarchy (Behl Reference Behl2017; Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2016). In other words, women/gender and politics courses suffer a lack of legitimacy because the field fails to accord the professors most likely to teach these courses (i.e., women) with the same legitimacy and authority of white male professors.

HYPOTHESES

Building on this previous research, we considered the state of women/gender and politics courses as part of the undergraduate political science curricula. We relied on a survey of instructors who teach this course to inquire about several relevant issues. Included among the issues were how the course fits within departmental and campus-wide curricula (i.e., major requirement or elective; general-education requirement or elective), which general topics are covered in the course; what training, if any, has the instructor had in women and/or gender studies; and whether there is resistance to teaching this course from students, colleagues, or administrators. We purposefully did not define “resistance” in our survey in order to capture a broad array of experiences that respondents defined as oppositional to their teaching women/gender and politics courses.

Based on findings from existing literature about intersectional biases, personal observation as instructors who teach women/gender and politics, and conversations with other instructors who teach this subject, we expected to find that:

H1: A majority of women/gender and politics courses count as electives rather than as core or major requirements.

H2: A majority of instructors who teach women/gender and politics courses experience resistance to this course from their colleagues, department, and/or institution.

H3: A majority of instructors who teach women/gender and politics courses experience resistance from students in these courses.

H4: Female instructors who teach women/gender and politics courses are more likely to experience resistance to this course from their colleagues, department, and institution than male instructors.

H5: Female instructors who teach women/gender and politics courses are more likely to experience resistance from students in these courses than male instructors.

H6: Women of color who teach women/gender and politics courses are more likely to experience resistance to this course from their colleagues, department, and institution than white women.

H7: Women of color who teach women/gender and politics courses are more likely to experience resistance from students in these courses than white women.

METHODOLOGY

We relied on an online Qualtrics survey to test our hypotheses and to gather information about training and content more broadly. To reach the population, we started with a list of all US universities and colleges with political science and/or government programs generated from Peterson’s (n=1,081). We then used course listings and online faculty biographies to identify political science faculty who teach women/gender and politics. This netted a list of 452 instructors who teach this course; we then identified 408 instructors with working email addresses to whom we administered the survey. A total of 181 instructors completed the survey for a response rate of 44.3%.

We administered our survey from March 23 to April 13, 2018, with an initial request to participate in the study and two follow-up reminders one week and two weeks later. Our survey included the following questions:

• How does your women/gender and politics course fit into the curriculum? General requirement, major requirement, elective, other (please specify)?

• Do you experience resistance to teaching this course from colleagues, department, school?

• Do you experience resistance in the classroom?

We also included several questions about each instructor’s training and experience teaching women/gender and politics (i.e., length of time teaching this course, specialization and training in graduate school, and shifts in teaching approach over the years) and the content of their course (i.e., assigned authors and topics covered). Many of these questions were open-ended, which enabled us to gather rich qualitative data in addition to quantitative outcomes.

This indicates that the norm is to assign women/gender and politics to women in the political science department who specialize in other topics as opposed to hiring faculty who specialize in the topic.

RESULTS

Most who teach this course identified as women (92.6%), whereas 6.1% identified as men and 1.3% identified as another gender. Respondents were mostly white (80.7%), whereas 4.4% were African American, 3.3% were Asian American, 2.5% identified as Latinx, and 1.1% were Native American.Footnote 2 Almost all who teach women/gender and politics had appointments in a political science department (93.4%), whereas 6.6% had a position in another discipline—namely, sociology or women’s studies. Most respondents (74.9%) taught women/gender and politics for at least five years, whereas only 6.2% taught the course for a year or less.

Regarding training, only 38.9% of respondents took courses on women and/or gender and politics in their PhD program. This means that the majority of those teaching women/gender and politics were women faculty members in political science departments who did not receive formal training on this topic. This indicates that the norm is to assign women/gender and politics to women in the political science department who specialize in other topics as opposed to hiring faculty who specialize in the topic. This is not a commentary on the quality of instruction of women/gender and politics courses because faculty often learn new topics for undergraduate courses. Rather, this suggests how political science continues to devalue formal training in this area.

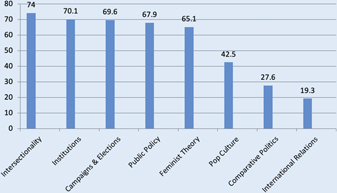

Regarding course content, those who teach women/gender and politics used a variety of textbooks, academic books, readers, and articles that cover a breadth of topics; most used a combination of academic books and articles. Instructors also reported variability in course themes and topics, although most of those surveyed approached the topic from an intersectional perspective and most covered political institutions (i.e., Congress, the presidency, and courts), campaigns and elections, and public policy (figure 1). Two thirds of respondents also included feminist theory as a course theme.

Figure 1 Percentage of Respondents That Teach Topic in Women/Gender and Politics

When we asked instructors how their approach to teaching women/gender and politics courses has changed over time, common themes emerged. The most common change made was inclusion of an intersectional lens. “Intersectionality” is the recognition that gender oppression intersects with other forms of oppression (e.g., race, sexuality, ability, and class); analysis of these intersections improves our understanding of the dynamics of gender oppression (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989). We did not include a specific question about intersectionality in our survey, but many instructors noted that this is one way in which they recently shifted their women/gender and politics courses. Other changes included focusing on masculinity, issues of transgender women and LGBTQIA people, and international relations/comparative politics (see appendix A).

We found support for five of our seven hypotheses. Our first hypothesis, a measure of mainstreaming, tested whether a majority of women/gender and politics courses count as electives or major requirements—in other words, whether the course was mainstreamed. We found that this course was not generally an institutional priority. Most women/gender and politics courses were counted as electives (83.9%), whereas 10.4% were counted as a major requirement and 2.4% were counted as a general requirement. One in five (21.8%) respondents reported that their women/gender and politics course is counted as something else at their institution; the most common response was that it is one (of many) options for major or general requirements and a requirement for a women and/or gender studies major or minor. Given that so few women/gender and politics courses were counted as a major or general-educational requirement, we accepted our first hypothesis.

For our second hypothesis, we asked whether instructors who teach women/gender and politics courses experienced resistance from their colleagues, department, and/or institution. Only 9.1% of those surveyed reported resistance from these sources. Although resistance is not common, it tends to come in one primary form: women/gender and politics is seen as unimportant to the study of political science because it is not authentically academic. Qualitative responses fit with these findings: political science departments fail to prioritize this course by counting it as an elective and assigning it to faculty who do not specialize in this topic (see appendix A). However, given that a majority of those who teach women/gender and politics reported no resistance from their colleagues, department, or administrators for teaching this course, we rejected our second hypothesis. Only about one in 10 instructors still experienced resistance from other faculty or their institution.

Qualitative descriptions of student resistance revealed three notable trends in the pushback: (1) general skepticism about the importance of gender as a variable worthy of study in political science; (2) criticism from conservative students; and (3) resistance to thinking about gender from male students (see appendix A).

For our third hypothesis, we found that slightly more than half (50.9%) in our study reported that those who teach women/gender and politics courses experienced resistance from students. Qualitative descriptions of student resistance revealed three notable trends in the pushback: (1) general skepticism about the importance of gender as a variable worthy of study in political science; (2) criticism from conservative students; and (3) resistance to thinking about gender from male students (see appendix A). Instructors reported a general resistance from students who think that women/gender and politics is not a topic worthy of study because they do not believe sexism exists. Another trend in qualitative descriptions of student pushback was criticism from politically conservative students who challenge the benefits of studying gendered power or find that the course content offends their beliefs. Faculty also reported the common theme of resistance from male students who are more critical than female students of course themes that challenge male privilege or otherwise make male students uncomfortable. Given that a majority of those who teach women/gender and politics reported resistance from students when they teach these courses, we accepted our third hypothesis.

For our fourth hypothesis, we did not find a significant difference between male and female instructors relative to resistance to this course from colleagues, department, and institutions. However, female instructors were significantly more likely than male instructors to experience resistance from students in women/gender and politics courses (51.7% compared to 40.0%; p=0.01), which supported our fifth hypothesis.

For our sixth hypothesis, women of color were nearly twice as likely to report resistance to teaching women/gender and politics courses from their colleagues, department, and institution than white women (15.0% compared to 8.3%; p=0.08). Women of color also were significantly more likely than white women to face resistance from students (68.4% compared to 44.5%; p=0.10), which supported our seventh hypothesis.

CONCLUSION

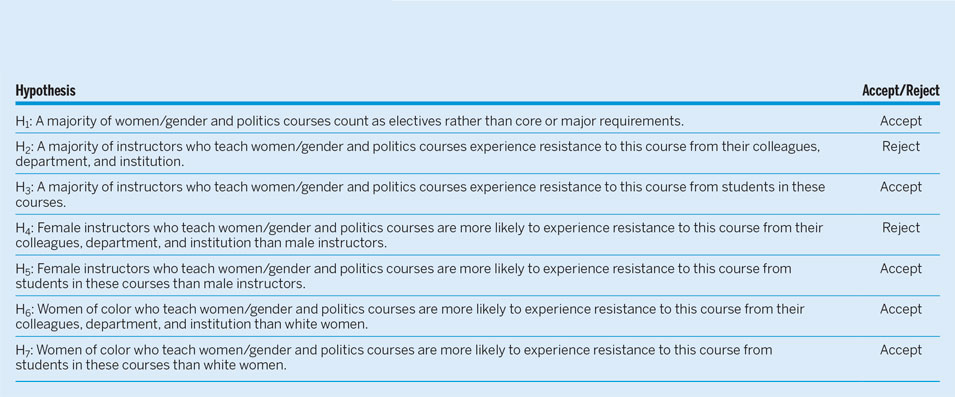

We tested seven hypotheses and found support for five (table 1). We found that institutions have not mainstreamed women/gender and politics in the department or general curricula. Few institutions require this class for the major, and fewer still offer it as a required general elective. We also found that whereas few faculty experienced resistance for teaching this course from other faculty members and administrators, women of color were significantly more likely to experience this. Faculty who teach women/gender and politics reported resistance from students in the form of general skepticism about the importance of studying gendered power/oppression and heightened criticism from politically conservative and/or male students. Male instructors faced similar student resistance as female instructors, but women of color experienced significantly more student pushback than white women who teach women/gender and politics.

Table 1 Summary of Findings

We also found that although women/gender and politics courses have become a fixture in the political science curriculum, they are still treated as tertiary to the study of politics. Furthermore, despite the gains of various feminist movements and women’s social, political, and economic advancement since the 1970s, a majority of instructors reported that students continue to resist thinking about gender as a meaningful variable in the political world. Also, women faculty of color faced more pushback for teaching women/gender and politics than other faculty members, which echoes previous findings of their precarity in academia. We see these three primary findings as connected in that institutions placing a low priority on women/gender and politics courses send a not-so-subtle message to students that this course is less important than other political science courses that have such designations. Faculty and administrators are no longer posing open resistance to offering women/gender and politics courses in the curriculum as in earlier years. However, administrators and political science departments continue to send the message that a women/gender and politics course is not primary to a well-rounded undergraduate education. Furthermore, faculty who are marginalized by their gender and race are especially susceptible to criticism when they teach women/gender and politics. Institutional prioritization of these courses cannot fully counter societal messages that this topic is not worth studying. However, making these courses a required part of the curriculum could go a long way in signifying the importance of studying women/gender and politics.

The pedagogical literature on teaching women/gender and politics suggests the need to familiarize students with gender-related issues, thereby expanding the idea of what is considered “political” and how to enact political change, encouraging consciousness raising among students, and promoting activism through experiential assignments (Buckley Reference Buckley, Ishiyama, Miller and Simon2015). In addition, intersectional analysis of the categories of race, class, gender, and sexuality as well as indigenous and feminist epistemologies in comparative perspective are essential to studying power in political science (Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2016; Tickner Reference Tickner2015). Perhaps mainstream political science failed to predict or adequately account for the rise and domination of masculinist, white supremacist politics in the past decade because the field marginalizes the study of identity and hierarchy and those who teach it. Political science must prioritize the study of hierarchies in order to capture the political dynamics it purports to understand.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000155