5.1 Introduction

This chapter explores three Australian redress programmes. Queensland’s Forde Foundation is a small in-kind programme similar to Ireland’s Caranua and was established prior to the more compensatory Queensland Redress. The latter half of the chapter addresses Western Australia’s complicated and troubled Redress WA.

5.2 The Forde Foundation

The 1997 publication of Bringing Them Home (Wilson and Dodson Reference Wilson and Dodson1997) highlighted the roles played by of out-of-home care in the genocide of Australia’s Indigenous Stolen Generations and spurred demands for monetary redress. In response, Queensland established the Commission of Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions in 1998, known as the Forde Inquiry after its chair Leneen Forde. Finding systemic abuse in out-of-home care, the Forde Report recommended that Queensland establish ‘principles of compensation in dialogue with victims of institutional abuse and strike a balance between individual monetary compensation and provision of services’ (Forde Reference Forde1999: xix).

The Forde Foundation was Queensland’s first response to that recommendation. Set up in 2000 as a perpetual fund, Queensland supplied its capital funding of AUD$4.15 million. The foundation continues to be governed by a government-appointed board whose ten members serve three-year terms. The board attempted to recruit survivors as members, but confronted conflicts of interest (AU Interview 2). The foundation’s three executive positions are supported by state funding. The Public Trustee administers the capital fund and between 2000 and 2019, the foundation distributed over 5,449 grants valued at around AUD$3.16 million (Forde Foundation 2019: 6).

All applicants must be registered with the foundation. Registrants must have been wards of the Queensland State, under its guardianship, or resided as a child in a Queensland institution. Registration is usually straightforward, supported by public records and facilitated by a community agency – Lotus Place (discussed later). There were 2,158 registered survivors in November 2021 (Private Communication from Eslynn Mauritz, Executive Officer of The Forde Foundation, 8 November 2021).

The foundation’s executive officer manages the funding application process. On average, the board receives around 1,000 applications per year, although numbers are increasing. As survivors age, they are more likely to seek more expensive support and, since the foundation is open to anyone who was in care in Queensland, the number of registrants grows every year (Terry Sullivan in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA6). The foundation gives informal priority to those who were in institutional care. There is no limit to the number of applications by any survivor, but they are now restricted to a maximum of AUD$5,000 in funding over five years.

There are three categories of application: dental, health and well-being, and ‘personal development’, which usually concerns education. The foundation will not fund publicly available goods or services, or those otherwise supported by private insurance. Monies are normally disbursed directly to providers. The foundation dispenses approximately AUD$50,000 each quarter, but this varies slightly from year to year to ensure the foundation’s’ perpetual sustainability. Funding decisions are made by a majority vote at the board’s quarterly meetings. Assessment is supposed to be holistic – including information available about the applicant’s life and previous choices, including the content and results of previous awards. However, as each meeting needs to consider around 250 substantial applications, the executive officer generates a short synopsis of each for the board to review (AU Interview 2). In general, dental services are simply approved: other applications receive greater scrutiny (AU Interview 2).

5.3 Queensland Redress

The Forde Foundation was (and is) a modest programme that spends around AUD$200,000 per year. Pressure for more substantive redress mounted throughout the 2000s (AU Interview 3). On 31 May 2007, Queensland announced a AUD$100 million programme for survivors of institutions investigated by the Forde Inquiry (Colvin Reference Colvin2007). A short (June–August) consultation process preceded the programme’s opening on 1 October 2007.

Queensland Redress began with a six-person team called Redress Services (AU Interview 2). The team originally expected 5,000–6,000 applications (Department of Communities 2009: 1). Applications came in quickly, eventually numbering 10,218 (Government of Queensland c2014: 2). Recruitment through secondments increased the staff to around fifty archivists, administrative officers, and project managers. The need to staff positions quickly, with a limited pool of available secondments, led to staffing compromises and high levels of turnover (AU Interview 2). The Department of Communities housed Redress Services, paying approximately AUD$12.3 million in administrative costs.Footnote 1 The department hosted a website (now defunct) with useful information, including the application form, some ‘Frequently Asked Questions’, and the Application Guidelines (Department of Communities 2008). The responsible minister published semi-regular media releases.

Redress Services served as the programme’s back office. The front of shop was Brisbane’s Lotus Place.Footnote 2 Lotus Place is a community centre offering counselling, support for records access and, during the programme, assistance in completing redress applications (AU Interview 1). The Forde Foundation was (and is) collocated at Lotus Place, as is the Aftercare Resource CentreFootnote 3 and, therefore, many Brisbane-based survivors were familiar with Lotus Place before Queensland Redress began, and the staff were equally experienced working with survivors. It is generally held that the work of Lotus Place as a one-stop ‘portal providing consistent information and assisting people [was] outstandingly successful’ (Robyn Eltherington in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA75). However, the number of applicants stretched Lotus Place’s resources. Lotus Place helped ‘over’ 2,000 applicants for redress, around 20 per cent of the total (Karyn Walsh in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA14). The converse is that 80 per cent either had no assistance or used non-funded services such as the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service. Rural and out-of-state applicants confronted significant accessibility challenges (Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2009: 89).

***

The application deadline was originally 30 June 2008, this was extended to 30 September 2008. Around 3,000 applications were received in that three-month period (Mark Francis in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA71). Received applications were assessed for completeness and survivors were contacted if material was clearly missing, but survivors could not amend their application after 28 February 2009. The programme accepted information in any format and the programme needed an upgraded information management system to manage the complexity of the material it received (AU Interview 2). The brevity of the twelve-month open period means that there are no records of the application rate, although one interviewee suggested that applications arrived steadily and almost immediately as survivor networks spread information about the scheme (AU Interview 2).

Eligibility for Queensland Redress required the applicant to have resided in one of the 159 institutions addressed by the Forde Report. This closed schedule of institutions created inequities, including racial discrimination. Legally, non-Indigenous children could only be placed in licensed institutions; however, some Indigenous children were placed in unlicensed institutions excluded from the Forde Inquiry and the resulting redress programme (AU Interview 3). Still, at the midpoint of the programme, June 2008, 53 per cent of the then 6,655 applicants identified as Indigenous (Lindy Nelson-Carr in ‘Child Safety’ 2008: 59).

Queensland Redress had two pathways, Level 1 and 2. Level 1 provided a uniform payment of AUD$7,000.Footnote 4 Survivors were eligible for a Level 1 payment if they had resided in a scheduled institution, were eighteen years or older on 31 December 1999, and had ‘experienced institutional abuse or neglect’ while in care (Department of Communities 2008: 3). The programme had five categories of abuse: psychological or emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, and ‘systems abuse’, the last referring to structurally injurious practices (Forde Reference Forde1999: iv–v, 12). These categories appeared on the application form as tick box options. To be eligible for a Level 1 payment, applicants needed only to tick a box that indicated they had suffered some form of abuse. Applicants were asked to name the institution(s) in which abuse occurred, then Redress Services would search for evidence of their residence. Residence could have been as short as a single day, but the programme excluded those who were in care during their first year of life only. Applicants needed to provide certified proof of identity (there were some multiple applications) and to authorise Redress Services to access relevant personal records. The information in the application form was confidential.

Care leavers could apply to Level 2 in their initial application or when notified of their Level 1 eligibility. Just under half of applicants (4,802) applied for a Level 1 settlement only. Level 2 responded to more serious injuries, including consequential harms, and required applicants to describe their injurious experiences in detail. The application form provided a short space to describe when injuries occurred and their duration, if the incident was reported, whether the applicant experience(d) consequential damages (the form suggests twenty-nine different harms), and whether medical treatment was sought or received (Department of Communities c2007: 5–6). Applicants were encouraged to submit any relevant documentation, such as police reports or medical statements. Redress Services did not provide funding for professional medical reports or other evidence of injury. This advantaged those who already had medical reports or could pay for them (AU Interview 1). However, most survivors simply described their experience in their own words. Applicants were not told how their information would be used: the assessment policy for Level 2 applications was not developed until after the programme opened to applications. A total of 5,416 survivors applied for a Level 2 payment (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2015b: 118).

A total of 15 per cent of applications to Level 1 were prioritised due to age or illness (Mark Francis in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA71). The programme did not accept posthumous applications, however, it provided AUD$5,000 towards the funeral expenses of those who would have been eligible. As many as 901 applications (9 per cent) were received from out-of-state survivors, but less than 1 per cent of applicants were overseas (Mark Francis in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA78–79). Incarcerated applicants offered a particular challenge. Because the programme accepted postal applications only, Redress Services set up an agreed confidential information system in which letters sent by inmates to the confidential postal address within the Department of Communities would not be read by prison staff. Payments for incarcerated applicants were held in a private trust until their release (AU Interview 3). Although prisoners are not permitted to have cash in prison, they might use the monies outside the prison for purposes within, such as bribery. This also helped imprisoned survivors avoid extortion.

All applications were assessed for a Level 1 payment. Because applicants who indicated an injury on the form were generally believed, Level 1 assessment primarily concerned institutional residence with records provided either by the applicant or sought by Redress Services. Only when no documentary evidence could be found did Redress Services revert to applicants for more information or a statutory declaration (AU Interview 2). Because Level 1 was administratively simple, on average, assessment took about one month (AU Interview 2).

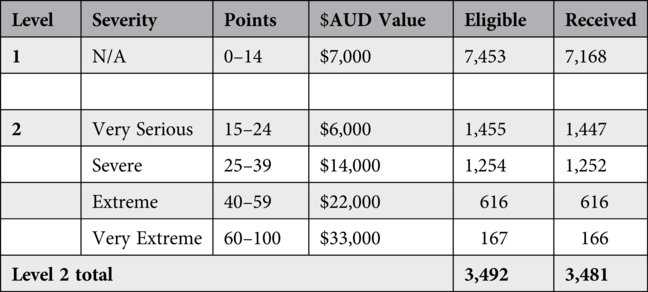

Level 2 assessment began in August 2008, after Level 1 was complete and the programme knew how much remained from the AUD$100 million fund (Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2009: 39). The process required more information, administrative resources, and time. The secretariat compiled a summary of each case file. Applications were then assessed by two members of a six-person panel of contracted lawyers. Those panellists did not conduct interviews (Department of Communities 2009: 3). They matched testimony from the application with evidence available from the Forde Report about the institution. In general, if evidence of residence was available, the programme accepted testimony that matched patterns described in the report (AU Interview 3). The panel then scored the application using a matrix (Appendix 3.3) that divided assessment into seven discrete analyses, giving greater weight to in-care experiences. Once each component was scored, the panellists aggregated the points to assign the application to one of five categories of severity ranging from a null award to ‘very extreme’ (see Table 5.1). The panel chair read the final assessment and verified the outcome.

***

Survivors accessed their records through a Freedom of Information process. Expert staff at Lotus Place provided applicants with support and guidance. Responding to the Forde Report, Queensland had digitised most relevant records. In 2001, Queensland also published Missing Pieces, a directory of the type and location of records held by public and religious bodies (Queensland Department of Families 2001). Those steps helped applicants compile their applications and facilitated cross-referencing. Around 80 per cent of applications were verified using departmental records (AU Interview 2). For the others, Redress Services searched for auxiliary records, such as school registers, and was flexible about the evidence it used (AU Interview 1). Moreover, during the Forde Inquiry, the state developed a ten-person ‘Administrative Release Team’ to respond to records requests (AU Interview 3). This team continued to help survivors access their personal records throughout the 2000s. This meant that a digitalised records-access infrastructure, with experienced staff, was available when the redress programme began.

Survivors confronted challenges in obtaining records nonetheless. Many records had been destroyed and what remained often lacked relevant information. Secrecy concerns surrounding adoption often meant that care staff tried to expunge the child’s relationship with their birth parents from documents. Those concerns also inhibited carers from creating and developing personal records. When relevant information was found, agencies redacted information that was not personal to the survivor. Rebecca Ketton of Aftercare observed ‘that often significant amounts of information is blacked out or crossed out with thick black pen. This can be quite upsetting …’ (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA39). Redacted information could affect a redress application, if, for example, an offender’s name was withheld. Files often used language hurtful to survivors and many survivors needed counselling support when accessing records (AU Interview 4). Specialist counselling was provided by Aftercare, an initiative of Relationships Australia. Another result of the Forde Inquiry, Aftercare operated a two-person branch in Lotus Place with in-person and telephone counselling. Aftercare also brokered counselling, both privately and through Relationships Australia offices, of which there were forty in 2009. When Queensland Redress ended in 2009, Aftercare had 860 clients, a 200 per cent increase over the term of the programme (Rebecca Ketton in ‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009a: CA42).

Queensland Redress did not pay for legal support during the application process. However, because the programme required survivors to waive all rights against the state for injuries suffered in care, survivors were instructed to obtain legal advice at the point of settlement. Applicants were provided with a list of solicitors willing to provide advice for a set fee (Bligh Reference Bligh2010). Redress Services paid those lawyers directly, at a total cost of AUD$3,468,750 (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2015b: 118).Footnote 5 The waiver only affected the survivor’s rights against Queensland. Financial advice was available to all applicants who accepted a payment. The programme would pay a set fee for an appointment with a financial advisor (Department of Communities 2008). This provision was not well utilised. One interviewee said, ‘We were always really clear about the legal fees and financial advice, but no one took us up on financial advice …’ (AU Interview 2). Kathy Daly reports that no applicant used the financial advice service (Daly Reference Daly2014: 140).

***

In December 2007, applicants began to be notified of their eligibility for Level 1 and sent the abovementioned waiver form. By 13 November 2008, over 3,270 Level 1 payments had been made and by April 2009 the total was over 6,000 – respectively 46 and 84 percent of the 7,168 final total (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2015b: 575). As many as 285 Level 1 payments went unclaimed, mostly by applicants with no known address. Survivors could appeal judgments to the Ombudsman or to the ordinary courts. That review only pertained to the question of institutional residence, never the actual assessment.

All successful Level 2 applicants were notified by letter in August 2009. This synchronised process was encouraged by the funding model in which eligible Level 2 applicants shared the AUD$45,349,000 remaining from the original AUD$100 million (Government of Queensland c2014). However, it also avoided the inequity of some applicants receiving settlements before others.

Every applicant in each of the Level 2’s four categories of severity was paid the same amount. The mean average payment was AUD$12,987, added to the AUD$7,000 for Level 1. Assessment information and monetary values were private; however, survivors were free to discuss their settlements publicly. Redress monies were not treated as income when assessing benefits and taxation. Towards the end of the programme, an issue emerged with Medicare, Queensland’s public health provider. Many survivors obtained redress for injuries for which they had previously received subsidised medical care, and Medicare began processes to recover its treatment costs from redress recipients. To protect survivors, Queensland paid Medicare a lump sum of AUD$500,000 to cover those repayments.

Table 5.1. Queensland Redress payments and values

| Level | Severity | Points | $AUD Value | Eligible | Received |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N/A | 0–14 | $7,000 | 7,453 | 7,168 |

| 2 | Very Serious | 15–24 | $6,000 | 1,455 | 1,447 |

| Severe | 25–39 | $14,000 | 1,254 | 1,252 | |

| Extreme | 40–59 | $22,000 | 616 | 616 | |

| Very Extreme | 60–100 | $33,000 | 167 | 166 | |

| Level 2 total | 3,492 | 3,481 | |||

5.4 Redress WA

On 17 December 2007, two months after Queensland Redress opened to applications, Western Australia announced a programme providing a Level 1 payment of AUD$10,000 and Level 2 payments up to AUD$80,000. Redress WA’s headline funding of AUD$114 million also looked larger than Queensland’s but it would need to pay the programme’s operational expenses, which would be around AUD$25 million. The programme opened on 1 May 2008 and closed to new applications on 30 April 2009. Then, on 26 June 2009, the government restructured the programme to create four tiers of payment with a maximum of AUD$45,000 (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2014c: 64). Partly a response to the unfolding global financial crisis, the AUD$45,000 maximum better communicated what survivors could reasonably expect, but the change undermined the programme’s credibility and led to vociferous criticism (Green et al. Reference Green, MacKenzie, Leeuwenburg and Watts2013: 2; Pearson, Minty, and Portelli Reference Pearson, Minty and Portelli2015: 7).

The post hoc change to the payment schedule reflected the fact that Redress WA was ‘introduced in an awful hurry’ and ‘with no infrastructure in place’. ‘It wasn’t well planned. It wasn’t planned at all’ (AU Interview 6). In 2007, state policymakers held two consultation meetings, but the development process lacked meaningful stakeholder involvement (Kimberley Community Legal Services c2012: 5; AU Interview 6). Located in the (relatively new) Department of Communities, when it opened in May 2008, Redress WA had fewer than ten staff. By 2010, the complement was around 130, yet the programme was never fully staffed. Most were seconded civil servants, but the demand for staff led to staffing compromises and the use of short-term contractors, contributing to high levels of turnover (AU Interview 8). This, in turn, led to administrative delays and high workloads that further aggravated staffing problems. Work was also hindered by a ‘clumsy and slow’ data management system (Western Australian Department for Communities Reference Rockc2012: 13). Delays frustrated claimants, leading to more complaints and hostility from many survivors (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 8). Redress WA did not have a publicly accessible office and staff were anonymised to shield them from media criticism and security threats. In the opinion of one interviewee, that made them ‘invisible’, with detrimental consequences for survivors (AU Interview 6).

Redress WA’s publicity strategy developed over time (Redress WA Reference Redress2008b). Originally, the programme expected 9,689 eligible applications (Redress WA Reference Redress2008b: 7). But the programme initially received much fewer than expected (only 328 applications by 31 August 2008) and the programme revised its publicity efforts, with more advertising (Rock Reference Rock2008: 5; Redress WA Reference Redress2008b: 11). Redress WA operated a website with useful information about the application process, available support, and updates on the programme. The programme produced a small number of newsletters, which it sent to registered applicants and published on its website.

Eligible applicants had to apply before 30 April 2009, with those who lodged an application having a further two months to complete it (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 17). Approximately 50 per cent of applications were submitted incomplete: some service providers simply submitted lists of names (AU Interview 9). Programme staff then had to contact applicants to complete missing information. Some service providers in remote Indigenous communities requested permission to submit late applications for survivors involved with traditional lore or sorry business,Footnote 6 and for those adversely affected by widespread flooding (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 10). Redress WA received 171 late applications, 27 were accepted.

Compensable injuries included physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse, and/or neglect (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 5). Applicants had to be eighteen on 30 April 2009, the original closing date of the programme. Applicants without identification documents could provide written statements from two referees. The programme did not have a schedule of specific institutions, but the state must have had formal responsibility for the survivor’s residential care at the time of the injury, which must have been prior to 1 March 2006. This was a firm parameter. Redress WA rejected applicants who had been informally placed in out-of-home care, this disproportionately affected Indigenous applicants (AU Interviews 8 & 9).

Redress WA accepted 5,917 applications for assessment. The application flow was marked by a significant increase during April–July 2009, when the programme received nearly 50 per cent of the final total (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 16). Western Australian residents submitted almost 90 per cent of the programme’s applications – half came from rural and/or remote areas: 42 per cent of applicants were under fifty years, and 49 per cent were male (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 3). Indigenous survivors submitted 3,024 (51 per cent) of applications. Former child migrants submitted 768 (13 per cent). Other groups were underrepresented, possibly because they lacked effective support organisations (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009b: 50). The eligibility requirement of having been ‘in state care’ may have dissuaded survivors of religious institutions who did not know they had been legally wards of the state (AU Interview 6).

Applications were prioritised if applicants had a terminal illness (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 26). Redress WA made 791 priority settlements of up to AUD$10,000 (‘Extract from Hansard, Hon Robyn McSweeney’ Reference McSweeney2010). Overpayments were not recovered. In September 2009, after twenty-nine applicants had died, the programme began to pay AUD$5,000 to the estates of deceased claimants (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 7). As many as 167 applicants passed away during the programme.

The fourteen-page application form asked survivors to describe the injuries they suffered and the consequential harms they incurred, along with time and place of any residence. Officials believed that less structure would encourage applicants to provide more accurate information. To avoid priming applicants, the form did not list potential forms of abuse or neglect, it simply asked applicants to provide ‘as much detail as possible’ (Redress WA Reference Redressc2008: 4). Most evidence was narrative, often handwritten, although other relevant documentation might be appended.

Completed applications were placed on a waiting list before the research team began to verify care placements. Redress WA undertook to search institutional records. This preliminary research might uncover other relevant material; however, ‘because of time pressures, the principal focus was verifying [residence in] state care’ (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 20). Redress WA compiled dossiers on larger care institutions. These dossiers gave a brief overview of the institution’s history; a summary of relevant policy and regulation; contemporary evidence of violations, including characteristic forms of abuse and neglect; and a list of alleged perpetrators. This was followed by summary information, for example, the institutional history of Bindoon Boys Town states ‘… sexual abuse was particularly rife in the late 1940s and through the 1950s’ (Redress WA 2008/Reference Redress2009: 7). That short statement offered supporting evidence for survivors who claimed that they were sexually abused in that period. The summary also noted typical aggravating factors, such as the frequency of vicious public punishment. The dossier might conclude with some references and photos. Dossiers varied in quality. None were substantial and smaller placements would have less-developed dossiers – foster care was excluded. Where possible, assessors batched applications by institution and time. This facilitated the use of similar fact evidence, as specific perpetrators might be mentioned in multiple applications. However, this batching could only be partial, as most applicants had resided in more than one institution.

Contemporarily accepted abuse and legal injuries, such as caning, were not eligible. Applying the standards of the day, education was similarly assessed – for example, leaving school at the age of fourteen was not injurious (Government of Western Australia 2010: 19). Indigenous survivors of the Stolen Generations were not compensated for having been removed from their culture, but elements relevant to injurious cultural removal might comprise consequential harm and/or be compounding and aggravating factors (Government of Western Australia 2010: 13–14). Initially, any award of more than AUD$10,000 required a psychological report, paid for by Redress WA (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009b: 54). This changed in 2010 and only applications assessed at Level 4 (AUD$45,000) needed medical evidence of injuries (AU Interview 8). If there was uncertainty whether the application was at Level 4, Redress WA might pay for a medical report, but the programme did not otherwise defray legal or medical costs. This after-the-fact change in policy meant that many applicants submitted unnecessary material, including psychological tests (Green et al. Reference Green, MacKenzie, Leeuwenburg and Watts2013: 4; AU Interview 6).

Having reviewed the application, institutional history, and any other relevant evidence, the case worker interviewed the applicant by telephone. During the interview, survivors could add information and interviewers might prompt applicants to provide relevant information, if, for example, research had uncovered a placement the applicant did not mention (AU Interview 9). In addition, the interviewer would seek clarification of, and evidence regarding, abuses or consequential harms described in the application. As some time had usually passed between the original application and the interview, new information was often available, including personal or medical records. These interviews helped moderate the variable quality of the initial applications, particularly for applicants with poor literacy (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 9).

Applicants were never interviewed in person. An internal document suggests that in-person hearings would be too stressful and ‘a form of secondary abuse in some cases’ (Government of Western Australia 2010: 12). Moreover, attendees at a hearing might seek legal representation, which would increase costs. Because telephone interviews could also retraumatise applicants, applicants could indicate that they did not want to receive a telephone call (Redress WA Reference Redressc2008: 2). These survivors were notified by letter when their application was assessed and invited to provide further information. Redress WA developed protocols to protect the privacy and quality of these interviews. But this preparatory work was not always successful.

What I heard time and time again was people saying, ‘Oh, I had my cousins over for lunch and I got a phone call, and it was the lady from Redress WA wanting to talk about my abuse and wanting more details about how I was sexually abused.’ Often, survivors aren’t assertive with authority, so they don’t say, ‘Well, can you ring back later’ or ‘Can we set up a time to do this later?’ So, they would just feel obliged to talk about really intimate and painful memories on the spot. That wasn’t fair …

Having assembled the facts, the case worker scored the application using a matrix (Appendix 3.6). This matrix was not published until after the programme closed to new applications. Assessors used four components: the experience of abuse and/or neglect; compounding factors, such as how isolated the resident was when abused; consequential harms; and aggravating factors, such as degrading treatment. Each component was worth twenty points. Redress WA developed a table (Appendix 3.7) to gauge injurious experiences, using indicative descriptions to help assessors score applicants according to severity. By subdividing each application into several categories, each comprised of various factors, Redress WA tried to capture individual nuance while retaining consistency. Assessors were encouraged to holistically reflect on the outcomes (Government of Western Australia 2010: 8–10).

Although the general categories of abuse and neglect match information sought on the application form, applicants were not told how the programme would assess severity. Moreover, the application form is silent concerning the role of compounding and aggravating factors. The form asks for information about consequential harm, but it does not mention salient subcategories. Some of this information might have been sought during the telephone interview, but it remains true that assessors used information that was only partially related to evidence requested by the application form. This non-transparency responded to widespread worries that survivors might tailor their testimony so as to obtain higher settlements (AU Interview 9). Peter Bayman, the programme’s senior legal officer, told a Senate Inquiry that ‘[w]e did not want to design a scale [for assessment] and then publish it so that it became essentially a cheat sheet’ (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009b: 56). Moreover, the assessment guidelines were not compiled until October 2008 – nearly six months after the programme opened – with the fourth and final version confirmed in May 2011 (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 41).

The case worker’s initial assessment was submitted to a team leader, who would reprise the assessment. If the totals varied, the judgement of the team leader was generally decisive (AU Interview 9). If an applicant was near the minimum score for a higher-level payment, they would often get moved up. Then, a senior research officer produced a ‘Notice of Assessment Decision’, that summarised the application and graded its severity. The programme notified applicants who were to be declined that they had twenty-eight days to provide further information. Applications categorised as severe or very severe were assessed a fourth time by an ‘Internal Member’ who was a lawyer. Internal members examined both the application and the assessment process, they might, for example, review the telephone interview transcript for evidence of leading questions (AU Interview 9). That fourth assessment could result in further requests for information or change the severity assessment. Once satisfied, the internal member submitted a report to the four-person Independent Review Panel that assessed the application again (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 20). The Review Panel did not need to use the matrices and could take a holistic view of the application. When it disagreed with the internal member, the panel tended to increase the settlement value (AU Interviews 8 & 9). Senior staff moderated the whole process to ensure that total costs would not exceed the capital funding. However, on 29 August 2011 the government provided a further AUD$30 million to cover any cost overruns.

With respect to evidentiary standards, Redress WA variously claimed to presumptively believe all claims by applicants (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 8); to have applied the standard of ‘reasonable likelihood’ (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 12); and to have tested evidence according to the ‘balance of probabilities’ (Government of Western Australia 2010: 11). In short, the standard applied depended on the payment value. Applicants pegged for lower level payments benefitted from a presumption of truth, (AU Interview 9), however, higher payments were assessed on the balance of probabilities (Government of Western Australia 2010: 31).

***

Twenty-six agencies were initially contracted to support applicants, with more engaged over time (Government of Western Australia 2007; Western Australian Department for Communities; c2012; Department for Communities 2009: 42). Redress WA published a booklet titled ‘Support Services for WA Care Leavers’ in November 2009 (Redress WA Reference Redress2009). Organisations were contracted to provide up to twelve hours of assistance for each survivor (Green et al. Reference Green, MacKenzie, Leeuwenburg and Watts2013: 4). The demands on key support services were significant. The Aboriginal Legal Service (ALS) submitted over 1,000 applications (Barter, Razi, and Williams Reference Barter, Razi and Williams2012: 7–10). Indeed, overwhelmed by the demand, at one point the ALS stopped accepting new clients (AU Interview 6). At one step removed, Redress WA’s helpdesk provided information to both applicants and service providers, receiving 500 calls, 100 emails, and about 20 text messages each week (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 4).

Redress WA received variable reviews concerning the support provided (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2014c: 66). For one survivor

… with Redress, you had people on your side offering you information, support. And, sure, there was a financial thing at the end of it, which was wonderful, but it was the fact that we had qualified counsellors in proper settings, a myriad of people we could call if we had any questions – they were on tap sort of 24 hours a day, seven days a week – and that did help immensely.

But another observer claimed that Redress WA initially failed to attract substantial numbers of applicants because it did not integrate well with support services (Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2009: 46). And support was needed. The ALS suggested that ‘participation in the scheme was traumatic for all involved’ (Barter, Razi, and Williams Reference Barter, Razi and Williams2012: 7). Phillipa White, coordinator of the Christian Brothers Ex-Residents Society, was ‘taken aback by the degree of distress and trauma’ involved (‘Official Committee Hansard’ 2009b: CA2). Counselling was provided by a number of service providers. Some contracted counselling services also assisted in developing applications, this could turn the application process into a more holistic assessment (Green et al. Reference Green, MacKenzie, Leeuwenburg and Watts2013: 4). Redress WA applicants could access three hours of individual counselling (Australia Reference Canada2009). Additional counselling could be arranged on request and Redress WA sponsored support groups across the state. By 2010, Redress WA had provided counselling services to 3,666 people (‘Extract from Hansard, Hon Robyn McSweeney’ Reference McSweeney2010). By the 2012 financial year-end, around 75 per cent of claimants had received application support and/or counselling at a total cost of AUD$3,814,000.Footnote 7

To help survivors access their personal records, Western Australia sponsored the 2004 publication of Signposts (Information Services 2004). Signposts is both a website and a 637-page print publication that lists over 200 relevant institutions, what records are available concerning each institution, where those records are located, and brief comments on their condition. But apart from Signposts, Western Australian undertook little preparatory work with records before Redress WA (AU Interview 7). The Department of Child Protection had primary responsibility for providing records and was rapidly overwhelmed by demand, with two-year delays from mid-2008 until 2011 (AU Interview 6). To manage, the department ceased providing full files, instead offering basic information about the place and duration of a survivor’s residency. By 2010, Redress WA was requisitioning and searching complete records itself (AU Interview 9).

There were good immigration records for child migrants. Some ‘Native Welfare’ records were on microfiche in good condition and some religious orders had archived their records with the state (AU Interview 7). Nevertheless, ‘the scant nature, fragmentation and destruction of departmental records often posed problems’ (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 9). Records were often ‘incomplete and paper-only’ making verifying the survivors’ residence in care ‘one of the most complex, time-consuming parts of the Redress WA process’ (Western Australian Department for Communities c2012: 18). Applicants needed to lodge a Freedom of Information Act request to receive their records, which approximately one-third did (‘Extract from Hansard, Hon Robyn McSweeney’ 2010). Third party information was redacted (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 23). Interestingly, complaints about redaction are not prominent among the primary sources.

Redress WA did not fund legal support because that would have reduced monies available for payments (Government of Western Australia 2010: 12). Originally, the programme was going to pay AUD$1,000 in legal fees to counsel applicants when signing waivers. However, when the programme decreased the maximum available payment, the programme abandoned the use of waivers. Nevertheless, as both Kimberley Legal Services and the ALS were contracted to support applicants, the 1,200 survivors they supported would have benefitted from legal advice (Kimberley Community Legal Services c2012; Barter, Razi, and Williams Reference Barter, Razi and Williams2012). Some survivors claimed to have spent more on legal fees than they received in the settlement (Pearson, Minty, and Portelli Reference Pearson, Minty and Portelli2015: 7).

***

The settlement offer included the proposed payment value, along with information as to where the survivor could find relevant personal records. For both reasons of privacy and welfare, the programme did not want to send sensitive and potentially distressing information to survivors without warning; therefore, explanations of the payment values were available only upon request (AU Interview 9). Approximately 1,300 applicants requested an explanation (Rock Reference Rockc2012: 5). Redress WA offered free financial counselling (Redress WA Reference Redress2008a: 16). However, I could find no information indicating that survivors commonly sought financial advice. Kimberley Community Legal Services indicates that ‘… few of the successful claimants received assistance to … [help them] … use their Redress money’ (Kimberley Community Legal Services c2012: 2).

Payments were generally by direct deposit. Monies could be placed in trust if the applicant was a prisoner or if the applicant was ‘mentally incapable of managing their own affairs’ (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 25). The ex gratia payments were not taxable nor charged against means-tested benefits. A very small number of people who had previously been compensated by the state had that money deducted from their settlements (Western Australian Department for Communities 2011: 15). No deductions were made for prior settlements with NGOs, such as churches. All successful applicants were offered a standard apology letter signed by the minister for communities and the premier of Western Australia. As many as 4,013 letters were issued (Department for Communities 2012: 57). Police referrals should have occurred when applications provided evidence of criminal offending, unless the survivor requested otherwise. The ALS advised that no Indigenous applicant would permit a police referral (AU Interview 9). However, if a child was presently in danger, a police referral was legally required. Redress WA made 2,233 police referrals (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2014c: 65).

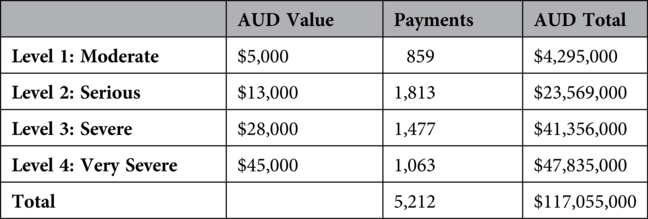

Originally, all payment offers were to be made before 30 April 2010 (Redress WA Reference Redress2008a). That did not happen. The first payments were issued in February 2010 (McSweeney Reference McSweeney2010). Afterwards, payments were made as assessments were completed: 1,300 were finalised by the end of 2010 and assessment continued until 30 June 2011 (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse 2014c: 63). The last payments were made in 2012. The final values are set out in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2. Redress WA levels and payment values

| AUD Value | Payments | AUD Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Moderate | $5,000 | 859 | $4,295,000 |

| Level 2: Serious | $13,000 | 1,813 | $23,569,000 |

| Level 3: Severe | $28,000 | 1,477 | $41,356,000 |

| Level 4: Very Severe | $45,000 | 1,063 | $47,835,000 |

| Total | 5,212 | $117,055,000 |

The programme paid the same amount to all survivors assessed at each level. The mean payment average was AUD$22,459. Survivors could request a review of errors of fact or process, but not the payment amount (Western Australian Department for Communities Reference Rockc2012: 21). Reviews were first conducted internally. If the applicant remained unsatisfied, they could complain to the Department of Communities. In both cases, the file could be referred to the Independent Review Panel, which had, in all cases of Level 3 and 4 assessments, already reviewed the assessment. Applicants could address a complaint to the State Ombudsman. Only nineteen appeals (0.3 per cent of applicants) affected the settlement outcome (Department for Communities 2012: 57).

***

With an emphasis on supporting applicants through community services, Australian redress ensured that many survivors could get help from local agencies and from people they knew. However, budget caps led to relatively low payment values, and particularly in the case of Redress WA, rushed implementation created delays and procedural instability. Important for my argument supporting survivor choice, Queensland Redress and Redress WA developed somewhat flexible pathways to redress that differed according to their eligibility requirements and assessment processes. That approach resonates with the Canadian programmes discussed in the next chapter.