When the United States entered World War II, women for the first time were mobilized in substantial numbers for noncombat military roles (Morden Reference Morden1990). Women and men alike were willing to sacrifice extensively to win the war: in December 1941, 91% of Americans supported the declaration of war on the Axis Powers (Saad Reference Saad2016). Given the overwhelming support for the war effort, it remains puzzling why recruitment targets were consistently missed. Ultimately, the US Army recruited only 133,000 volunteers of its 300,000 target for the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) (Morden Reference Morden1990). Women from all walks of life had the opportunity to volunteer, but significant variation in volunteerism rates persisted across geography, class, partisanship, and other demographic indicators. Which factors influenced female volunteerism—or the lack thereof?

We argue that sexism and racism may have kept some women from serving. Local social pressure to not join the military and sustained campaigns that disparaged women in the military worked against government efforts to encourage women to volunteer (Campbell Reference Campbell1984). Black women faced additional obstacles to volunteerism, from Jim Crow laws in the South to hostile enlistment officials across the country.

We used original data on every US Army volunteer during World War II to evaluate these propositions (Artiles et al. Reference Artiles, Treneska, Fahey and Atkinson2023). We aggregated these data to the county level and linked them with electoral and US Census data to explore female volunteerism rates during the war. Our data allowed us to explore the relationships between economic, political, and demographic factors and women’s military enlistment. Understanding these relationships not only sheds light on an understudied historical case but also may offer insights into current inequities in military service.

Our research makes two significant contributions. First, we augment existing theories of motivations for military volunteerism by incorporating broader structural and societal factors. Existing research on the determinants of wartime volunteerism focuses on two factors: institutional (intrinsic) and occupational (extrinsic) motivators (Moskos Reference Moskos1977). Scholars have found that these motivations often operate in conjunction (Cancian Reference Cancian2021; Eighmey Reference Eighmey2006; Humphreys and Weinstein Reference Humphreys and Weinstein2008). Furthermore, we suggest that “push and pull” factors influencing decisions to volunteer for military service operate within a broader structural and societal context. These factors have a profound effect on individual decision making, especially those for whom the structures are intended to exclude (Bateson Reference Bateson2020; Conkel, Gushue, and Turner Reference Conkel-Ziebell, Gushue and Turner2019; Ditonto Reference Ditonto2019). Accounting for racism and sexism toward female volunteers complements existing narratives and, for the first time, we may observe individuals with the incentive to serve but who were kept from service by structural barriers.

…for the first time, we may observe individuals with the incentive to serve but who were kept from service by structural barriers.

Second, we introduce an original dataset that contains detailed information on all volunteers who served in the US Army during World War II: the Soldiers of the Second World War dataset. These data are drawn from a larger original dataset of all enlistees in the US Army during the war (Atkinson and Fahey Reference Atkinson and Fahey2022). The US Department of War compiled details about its enlistees in a raw, unusable format and only released them to the public in 2002. We extensively prepared these data for various quantitative research purposes. Our dataset contains every enlistee’s date of birth, state and county of residence, enlistment date, prewar occupation, education level, race, gender, and ancestry. This finished dataset has potential applications across subfields and disciplines from historical analysis, sociological studies, and political behavior, to the study of how countries mobilize for war. (See online appendix B for a detailed description of the dataset.)

We discovered three major patterns in female enlistment during World War II. First, counties with higher female college-graduation rates observed more than 9,000 additional volunteers across the country each year. Second, counties with higher racial segregation observed more than 3,000 fewer volunteers. These findings are consistent with our broader argument that sexism and racism deterred female volunteerism, and they emphasize that institutional prejudices hindered the war effort. Third, counties with higher civilian wages in the manufacturing, retail, and service sectors witnessed substantially higher female enrollment by tens of thousands.

THE WOMEN OF WORLD WAR II

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, thrusting the United States into a two-front war against Japan, Germany, and Italy. The war ultimately would require the service of 16 million Americans. To meet the labor demands of the war, the US government relied on a selective conscription scheme, first implemented in 1940. Additionally, the US Congress established the all-volunteer WACs in May 1942 to supplement the number of noncombat military personnel and additional auxiliary corps for the other services (Bellafaire Reference Bellafaire1993). Ultimately, almost 350,000 women would serve in the armed forces, including 133,000 WACs (figure 1). Women were critical for the war effort: female volunteers in the US Army drove and repaired military vehicles, served as clerks, worked in office jobs, and conducted intelligence collection, among other roles (Bellafaire Reference Bellafaire1993).

Figure 1 Female Volunteer Rates by County, 1943

Darker gray indicates lower volunteerism, lighter gray indicates higher volunteerism.

THE INFLUENCES ON FEMALE VOLUNTEERISM

We assume that individuals are rational when choosing to volunteer for military service. They weigh the costs and benefits of military service, maximizing their utility. The costs and benefits of service come from both internal and external motivators (Moskos Reference Moskos1977). Internal motivators include patriotism, religious beliefs, wages, a sense of duty, and educational opportunities. External motivators include structural forces such as military regulations that (dis)encourage service for certain demographic groups. For example, the US military limited the opportunities available to Black women during World War II to menial labor (Bolzenius Reference Bolzenius2018). External motivators also include social pressures that push people toward or pull them away from military service. For example, conservative communities promoted traditional gender norms and disapproved of women joining the military (Permeswaran Reference Permeswaran2008). The following discussion theorizes several of the costs and benefits that influenced women’s decisions to volunteer.

The first factor that shaped female volunteerism was the societal stigma around women serving in the military. Women feared the social sanctions from their communities—family and friends, political elites, and mass media—if they joined the military (Permeswaran Reference Permeswaran2008). We argue that these social sanctions were most potent in culturally conservative communities that observed strict gender norms. In these communities, women were encouraged to stay in the household and discouraged from engaging in nontraditional activities, including educational attainment and labor-force participation (Glass and Jacobs Reference Glass and Jacobs2005).

In a prewar context, an appropriate proxy for the intensity with which a community held these traditional gender norms was the propensity for its women to obtain higher education. Culturally conservative values are associated with lower female educational attainment (Glass and Jacobs Reference Glass and Jacobs2005). Many conservative communities perceived female higher education as violating “the ideal of true womanhood” (Graham Reference Graham1978, 759). As a result, communities that were more comfortable with women pursuing higher education would be more willing to accept women assuming other nontraditional roles, such as military service.

If a woman’s surrounding community objected to her enlisting, she likely would have felt conflicted about doing so. For women in progressive communities, volunteering was far less costly. Therefore, communities with more female college graduates would observe more volunteerism.

Education Hypothesis: Counties with higher proportions of women with college degrees will have higher enlistment rates compared to counties with lower proportions of women with college degrees.

The second factor that shaped volunteerism was racial discrimination. Volunteering for the military was extremely costly for Black women, who had to overcome obstacles due to both her gender and her race. Blacks comprised only 1% of local draft board members during World War II, leaving Black women’s enlistment primarily in the hands of white men—who often did not believe that they belonged in the military (Murray Reference Murray1971).

Many communities adopted recruitment rules that were responsible for gatekeeping potential volunteers on the basis of race. Although the military had no educational requirements, it eventually implemented literacy requirements—through the Armed Forces Qualifications Test (AFQT)—that adversely affected Black women. As a result of racial disparities in the US public educational system, Black women scored significantly lower than white women on the AFQT, particularly in segregated Southern communities (Moore Reference Moore1991). When Black women did pass the AFQT, local draft boards often delayed their enlistment by several months, claiming a lack of adequate training facilities (Murray Reference Murray1971).

All of these challenges make it unsurprising that Black women never comprised more than 4% of the WACs. For Black women, attempting to enlist was extremely costly. Therefore, communities with more racial strife would observe less volunteerism.

Race Hypothesis: Counties with higher levels of observable segregation will have lower enlistment rates among Black women compared to counties with lower levels of observable segregation.

The third factor that we examined was economic opportunity. During World War II, labor shortages led to significant increases in civilian wages (Schumann Reference Schumann2003). Increased wages at home primarily benefited men (Aldrich Reference Aldrich1989). Most women who entered the labor market did not take over the jobs of enlisted men or the jobs that men who stayed home wanted. Instead, most women competed for newly created jobs (Rose Reference Rose2018). These jobs were geographically concentrated, temporary, and lower paid; in 1942, a woman working in a civilian job earned 53 cents to a man’s dollar (Aldrich Reference Aldrich1989).

In 1943, Congress passed an equal-pay provision for the WACs. Men and women from all racial backgrounds received equal pay according to rank and, with a few modifications for WACs, almost the same benefits (Bolzenius Reference Bolzenius2018). For many women, these regulations provided opportunities that were unimaginable at home. Increased pay and benefits may have partially ameliorated the high societal costs described previously.

We anticipated that as wages rose in a county, an influx of men seeking higher wages would drive the local women to take lower-paid jobs; thus, joining the WACs became more attractive. We expected women in counties with higher wages to face more costs in the civilian workforce and to view military service as more desirable.

Wages Hypothesis: Counties with higher wages will see higher enlistment rates compared to counties with lower wages.

DATA AND METHODS

To test our hypotheses, we analyzed a novel dataset of all female volunteers in the US Army during World War II (1941–1945), compiled by the US Department of War and converted into the Soldiers of World War II dataset.Footnote 1 Workers at local induction stations took the data from enlistees and entered this information on punch cards for use on early computers. Decades later, researchers at the National Archives and Records Administration combined these records into ASCII files. We cleaned these files and converted them into a format usable for analysis. This dataset contains every enlistee’s date of birth, state and county of residence, enlistment date, prewar occupation, education level, race, and ancestry.

To test our hypotheses, we analyzed a novel dataset of all female volunteers in the US Army during World War II (1941–1945), compiled by the US Department of War and converted into the Soldiers of World War II dataset.

To address the immediate research questions in our study, we created another subset of our enlistments to women who served. Although the records do not indicate the gender of the enlistee, we could obtain this information using the enlistees’ serial numbers. Female enlistees had an “A” placed before their serial number to indicate that they were a member of the WACs. In total, we had access to more than nine million service-member records, of which 133,843 were women in the WACs.Footnote 2 Ideally, we would have compared predictors of volunteer rates at an individual level; however, crucial granular, individual-level partisan, demographic, and economic data do not exist. Therefore, we aggregated information to the county-year, resulting in a balanced panel of 15,580 observations for 1941–1945. This approach allowed us to compare the influence of various county-level attributes on that county’s female volunteer rate.

Dependent Variables

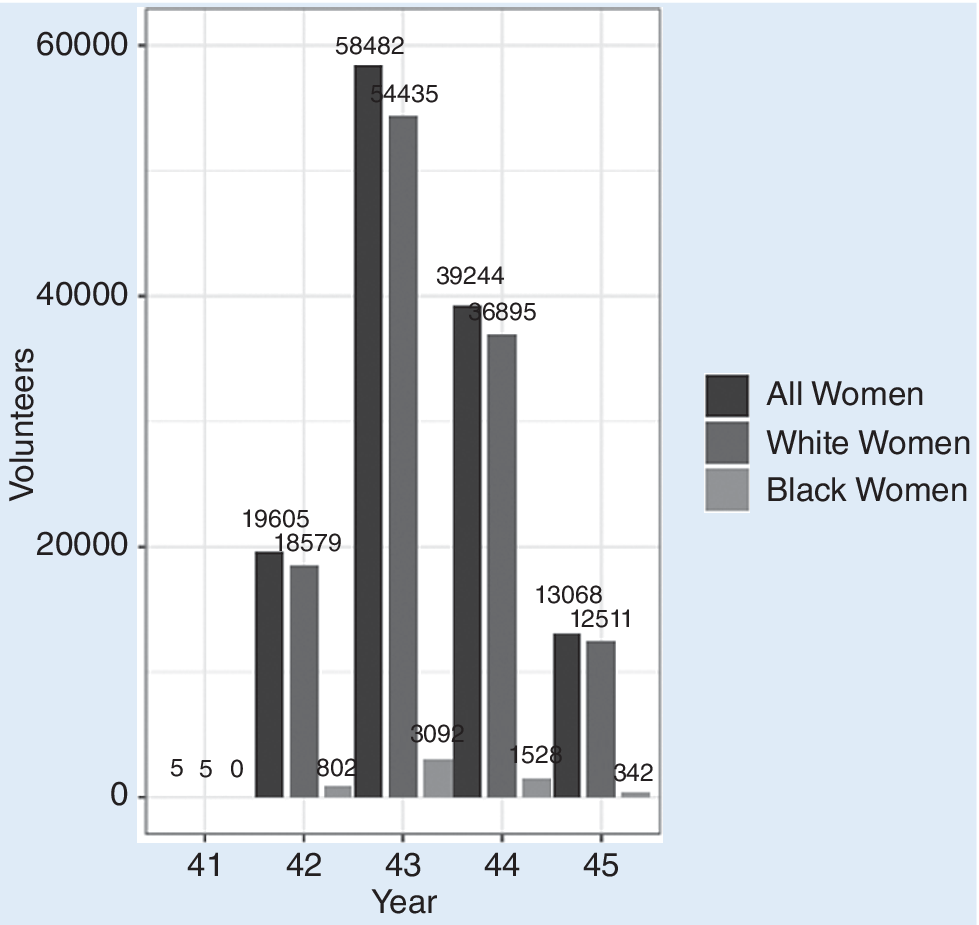

Our first outcome measure was the proportion of female volunteers in a county-year. We created additional subsets for white volunteers and Black volunteers.Footnote 3 Figure 2 presents the number of volunteers by year.

Figure 2 Female Volunteers, 1941–1945

Independent Variables

Consistent with the Education Hypothesis, women from counties with higher rates of female college education would have higher enlistment rates. The distribution of college-educated women by county is shown in figure 3. Consistent with the Race Hypothesis, areas with more overt racial segregation should have had lower volunteerism rates, particularly Black volunteers. We operationalized county-level racial segregation with the two reliable measures of racial segregation used by Logan and Parman (Reference Logan and Parman2017). The first is the isolation index, which measures the probability that a member in one group (whites) will interact with a member of another group (Blacks). The isolation index ranges from 0 to 1, in which higher values indicate lower segregation. The distribution of neighborhood isolation is illustrated in figure 4. The second measure is the dissimilarity index, which measures the percentage of a group’s population that would need to change residence for each neighborhood to have the same percentage of that group. The dissimilarity index also ranges from 0 to 1, in which higher scores indicate higher segregation. To test our Wages Hypothesis, we included county-level information on economic indicators, including wages in the four major US Census sectors: manufacturing, retail, wholesale, and service (Dodd and Dodd Reference Dodd and Dodd1973).

Figure 3 Female College-Graduation Rates by County, 1940

Darker gray indicates fewer graduates, lighter gray indicates more graduates.

Figure 4 Racial-Isolation Rates by County, 1940

Darker gray indicates higher segregation, lighter gray indicates lower segregation.

We controlled for two partisan indicators: county-level vote shares for President Roosevelt and the Democratic candidate for the US House of Representatives (Haines Reference Haines2005). We also included county-level demographic data, such as the percentage of white women and men, the percentage of Black women and men older than 21,Footnote 4 the proportion of the urban population, and the total population.Footnote 5

To analyze these data, we used ordinary-least-squares (OLS) regressions with state-year fixed-effects and clustered standard errors.Footnote 6 The first model was all female volunteers, the second model was all white female volunteers, and the third model was all Black female volunteers.Footnote 7 In reporting our analyses, we show estimated coefficients on separate figures—although they originated from the same models—to highlight results by hypothesis.Footnote 8

RESULTS

Figures 5 and 6 report the estimated coefficients for education, racial dissimilarity, and racial isolation. We found a positive, marginally significant relationship between college education and white female volunteerism at the p<0.01 level. Substantively, a one standard-deviation increase in education results in 3.14 additional female volunteers per county-year. With 3,116 counties in our sample, the substantive impact is substantial, equal to 9,784 additional volunteers in the United States in a year. There was both statistical and substantive support for our Education Hypothesis: college education was associated with increased female volunteerism.

Figure 5 Coefficient Plot of Influence of College Education on Female Volunteerism with 95% Confidence Intervals

Figure 6 Coefficient Plot of Influence of Racial Variables on Female Volunteerism with 95% Confidence Intervals

We found a negative, statistically significant relationship between racial dissimilarity (i.e., higher segregation) and Black female volunteerism at the p<0.01 level. We also found a positive, statistically significant relationship between racial isolation (i.e., lower segregation) and Black female volunteerism at the p<0.01 level. This demonstrates support for the Race Hypothesis because counties with lower isolation and dissimilarity scores were associated with higher female volunteerism. The substantive significance for our racial variables was small, with a one-standard-deviation increase in dissimilarity (i.e., higher segregation). This resulted in about one less volunteer per county-year, or approximately 3,000 fewer volunteers throughout the United States in a year. This may be because more progressive counties had fewer institutional roadblocks for women of color hoping to enlist.

Figure 7 reports estimated coefficients for our set of economic variables. All four of our wage variables were statistically significant. Both manufacturing wages and retail wages had positive, statistically significant influences on female volunteerism at the p<0.01 level. Service wages had a positive, statistically significant influence on female volunteerism at the p<0.05 level. It is interesting that wholesale wages had a negative, statistically significant influence on female volunteerism at the p<0.05 level. We did not find significant evidence for unemployment. In terms of substantive significance, a one-standard-deviation increase in wages increased the number of female volunteers by 2.70 (manufacturing), 10.87 (retail), and 8.94 (service) per county-year. This is equal to 8,413 (manufacturing), 33,871 (retail), and 27,845 (service) throughout the United States in a year. A one-standard-deviation increase in wholesale wages decreased the number of female volunteers by 7.85 per county-year. We found considerable support for our Wages Hypothesis: even when wages in several fields increased, so did female volunteerism. This suggests that as wages rose in these sectors, young women were not taking civilian jobs—possibly because they experienced increased competition from men for those more lucrative jobs.

Figure 7 Coefficient Plot of Influence of Economic Variables on Female Volunteerism with 95% Confidence Intervals

Figures 8 and 9 report the coefficients for our controls. We found a positive, statistically significant influence of urbanism on female volunteerism, significant at the p<0.05 level. The percentage of white females in a county had a negative, marginally significant influence on volunteerism at the p<0.1 level. We did not find significant evidence for the county-level vote shares for President Roosevelt; for county-level vote shares for the Democratic congressional candidate; or for the percentage of white males, Black females, or Black males in a county.

Figure 8 Coefficient Plot of Influence of Political Variables on Female Volunteerism with 95% Confidence Intervals

Figure 9 Coefficient Plot of Influence of Demographic Variables on Female Volunteerism with 95% Confidence Intervals

In summary, we found sizeable support for our hypotheses. Increased college education; lower levels of racial segregation; and wages in the manufacturing, retail, and service sectors were all associated with increased female volunteerism. Wholesale wages were negatively associated with volunteerism. Some controls also were interesting: urbanism and the percentage of white females in a county were positively associated with increased volunteerism.

In summary, we found sizeable support for our hypotheses. Increased college education; lower levels of racial segregation; and wages in the manufacturing, retail, and service sectors were all associated with increased female volunteerism.

CONCLUSION

This article is an overview of the motives for female volunteerism in the US military during World War II. Whereas previous literature focused on potential intrinsic and extrinsic individual-level motives, we considered the broader structural context that may have played a role in female volunteerism. Using a novel dataset of all volunteers who served in the US Army during World War II, we found that a combination of political and economic factors influenced female volunteerism. Counties with higher female college-graduation rates had a higher rate of female volunteers. Counties with less observable racial segregation observed higher rates of Black female volunteers, which implies that more socially progressive counties had fewer institutional roadblocks for women of color. Finally, counties with higher manufacturing, retail, and service wages had higher rates of female volunteers. This finding is contrary to the claim that women were offered higher-paying civilian jobs due to men enlisting and therefore had fewer incentives to volunteer in the military.

The significance of this research is twofold. First, it introduces a novel dataset of broad interest to political scientists across subfields, from scholars of gender and politics, race and ethnicity, and political behavior to international relations. Second, it is the first review of the county-level demographic and economic factors that shaped female volunteerism during World War II. Many of these factors led to fewer women and women of color volunteering in the military at a time when volunteering was most needed. It is important to consider these results when conducting future research in this field and to assess whether such patterns are in evidence today.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EFW7U8.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S104909652300015X.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.