Chapter Three Ceremonial Armatures: Porticated Streets and Their Architectural Appendages

3.1 Prolegomena to Porticated Streets

Albeit with notable exceptions, modern scholars have tended to underestimate the importance of colonnaded (or porticated) streets in the urban fabric of late antique cities, particularly in the West.1 Even with regard to the East, where the majestic colonnaded avenues still visible in cities such as Palmyra, Apamea and Ephesus bring the monumental presence of these prepossessing features powerfully to life, there is nonetheless a continued inclination (again with notable exceptions) to propose their de-monumentalization by the later sixth century at the latest, following what remains a hallowed locus communis, the metamorphosis of the grand colonnaded thoroughfare of antiquity into the pullulating chaos of the medieval suq. Jean Sauvaget’s schematized diagram representing the chronological (d)evolution of the colonnaded street in his study of Laodicea of 1934,2 still often cited and reproduced, has become emblematic of the idea that even before the Arab conquest in the seventh century, colonnaded streets had seen their pristine monumentality compromised by the encroachment of shops and residences haphazardly built into the spaces between the columns and thence outward onto the paving of the streets themselves. Hugh Kennedy’s influential article of 1985 translated Sauvaget’s diagram into a paradigm more generally applicable to the cities of the Levant, which in his formulation were well on their way to becoming the teeming bazaars characteristic of the medieval period by the later sixth century;3 and Helen Saradi has recently further extended the presumed range of the phenomenon to the ‘Byzantine city’ of the sixth century in general.4

As we shall see, this perspective requires substantial modification. At least as late as the fifth century in the western Mediterranean and the sixth in the East, porticated streets were either refurbished or built anew with remarkable frequency, joining city walls and churches as much the most prolific monumental architectural forms of the era. Further, the partition walls and structures in generally irregular masonry or more perishable materials that ultimately did come to encroach on the intercolumnar spaces and sometimes – more to the point – the roadbeds of so many colonnaded streets are often extremely difficult to date even for methodologically advanced archaeologists. As the majority of the extant remains were uncovered before the widespread use of rigorously stratigraphic excavation techniques in the past few decades, the essential question of chronology remains very much open. Much of the encroachment once dated to the sixth century largely on the basis of a priori notions about the inexorable decline of the classical townscape already in that period may well belong to the ninth century or later.5 There are indeed a number of tantalizing indicators of the continued vitality of some streets, in both East and West, into the seventh and eighth centuries, when they apparently continued to frame the unfolding of urban ceremony in ways that suggest that their accessibility and their imposing architectural presence had not been fatally compromised either by unchecked decay or by the installation of shops and other commercial establishments, which had indeed been a ubiquitous presence in porticated streets throughout late antiquity, as we shall see, and for that matter under the high empire as well.6

Before proceeding, there is a brief matter of terminology and definitions to clear up. Strictly speaking, a colonnade is composed of columns, bearing either a flat (trabeated) entablature, or a series of arches (an arcade). In the West more often than the East (where the proximity of good sources of marble permitted a ready supply of monolithic columns), the trabeated and arcaded structures flanking streets were often supported by pillars of masonry or even wood, whence they cannot properly be called colonnades.7 Hence, I will hereafter prefer ‘porticated streets’ as a catchall designator for all such structures, and ‘colonnaded streets’ in the more restricted sense of the term. There is the further issue of what exactly constitutes a porticated street: my discussion of these structures will focus on streets lined by lengthy porticoes of relatively uniform aspect, as opposed to streets flanked by buildings with their own irregularly sized and spaced porticoes giving onto the roadbed, which will have presented a more heterogeneous and discontinuous appearance. A porticated street constitutes a cohesive architectural scheme that transcends the character of the individual structures situated behind the porticoes, imbuing the street as a whole with an architectonic identity essentially independent of the adjacent buildings, for all that these buildings are often directly connected to the porticoes.8

It should also be stressed that such streets started to proliferate long before late antiquity, beginning in the first century AD. The longest and perhaps the earliest of all is the cardo at Antioch, repaved and widened by King Herod at the turn of the millennium and lined on both sides, for its entire length of 2,275m, with continuous files of columns by the mid-first century AD.9 By the later second century, extensive colonnades lined both sides of one or more principal streets at cities across the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, as well as at Rome itself and at a number of sites in western Europe (e.g., Lincoln, Reims, Italica), though the Eastern exemplars usually receive considerably more attention, as they tend to be both more monumental and better preserved.10 It was only with the imperially sponsored urban or quasi-urban foundations of the third century, however, that the colonnaded or porticated street came into its own as an indispensable element in the architectural language of imperial power, East and West, from Philippopolis in the 240s to the palace-city complexes erected by the Tetrarchic emperors, as we saw in the preceding chapter.

Thereafter, porticated streets became (with the exception of city walls) the most ubiquitous, expensive and ambitious form of secular monumental architecture erected from the later third century through the sixth, leaving an indelible stamp on the greatest cities of the late Roman – and post-Roman – world, and many others besides. The majority of the most extensive and costly street porticoes either restored, extended or constructed ex novo were located in prominent centers of civic and ecclesiastical administration, provincial and imperial capitals above all,11 which increasingly tended to gravitate around the colonnades that framed and connected the palaces and churches where rulers and bishops lived and performed their public duties.

Hence, an inquiry into the question of why the civic and, to a lesser extent, ecclesiastical authorities responsible for the most ambitious interventions in the urban topography of late antique cities devoted such a considerable portion of their limited resources to porticated streets should have much to reveal about the ways power and authority were enacted, publicized and given architectural form in the late Roman world. It should also help to explain the motives behind the development of the porticated street into the ‘imperial’ architectural feature par excellence in the third century, and the surprising persistence of these streets, and – more to the point – the ceremonial and commemorative praxis associated with them, through the sixth century and beyond in both East and West. Hence, the function of these grand avenues will concern us at least as much as their form. Our focus will be on the period ca. 300–600, which is rich enough in literary, epigraphic, archaeological and iconographic evidence to permit a relatively detailed perspective on the activities and ideological constructs that animated these streets and made them such indispensable features of the greatest cities of the epoch.

3.2 Imperial Capitals in Italy: Rome and Milan

In a fine recent article on colonnaded streets in Constantinople in late antiquity, it is stated that the city of Rome differed markedly from Constantinople in that it had no colonnaded streets worth speaking of in late antiquity.12 In reality, Rome had long featured extensive street porticoes. The most ideologically charged route in the city, the Triumphal Way followed by returning conquerors since the early days of the Republic, came to be lined by covered stone arcades over much or all of its urban tract, from the Bridge of Nero in the Campus Martius, through the Circus Flaminius and the Forum Boarium, and on past the Circus Maximus to the Forum Romanum.13 Elsewhere, following the catastrophic fire of AD 64, a number of principal thoroughfares in the devastated city center were reconstructed as wide, porticated avenues, which imbued the imperial capital with a stately veneer reminiscent of the royal capitals of the Hellenistic eastern Mediterranean.14 Nero’s gargantuan new palace, the domus aurea, gravitated around a triple portico said by Suetonius to be a mile long;15 and Nero’s architects encased the nearby Sacra Via – the final stretch of the Triumphal Way running through the forum to the Capitoline Hill – within lofty, arcaded porticoes at the same time.16

But the most extensive evidence for the erection of monumental street porticoes at Rome comes from late antiquity, beginning in the later fourth century, when several of the busiest and most symbolically charged axes of communication in the city were embellished with extensive porticated façades. Indeed, one of the most significant architectural interventions witnessed in Rome in the second half of the fourth century involved the erection of new porticoes along what was then becoming one of the very most important roads in the city, the street leading north through the Campus Martius to the Pons Aelius, the bridge leading to the mausoleum of Hadrian, and from there onward to St. Peter’s. As the evidence for the monumentalization of this street has been presented elsewhere,17 a resume of the salient points will suffice.

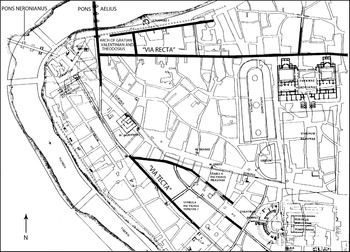

At the time of or soon after the construction of the Aurelian Wall in the 270s, the Pons Neronianus, the old Neronian bridge that served as the principal connection between the northern Campus Martius and the west bank of the Tiber, went out of use.18 Thereafter, all traffic on the two main roads in the area, the so-called Via Recta (the modern Via dei Coronari) leading east through the Campus Martius past the Baths of Nero and on to the Via Lata, and the Via Tecta, the porticated road running northwest from the Circus Flaminius, effectively the urban continuation of the ancient Via Triumphalis (the modern Via dei Banchi Vecchi), was diverted northward to the bridge leading to the Mausoleum of Hadrian, which subsequently became the sole crossing point in the northern Campus Martius. The decision to privilege the previously little-frequented Pons Aelius over the Pons Neronianus was presumably conditioned by defensive considerations, as the mausoleum was admirably suited to function as a fortified bridgehead on the far bank of the Tiber, allowing access to the bridge to be strictly controlled in a way that would have been impossible at the Pons Neronianus without the addition of substantial new structures at its western approaches. Traffic on the ‘Via Recta’ and Via Tecta was subsequently diverted north to the Pons Aelius along the modern Via del Banco Santo Spirito, as can be deduced in part from the fact that almost no traces of the paving of the ‘Via Recta’ and Via Tecta have been discovered between the point where they converged on the road leading to the mausoleum and the Pons Neronianus;19 the paving of these streets may indeed have been reused to monumentally re-edify the tract of road leading to the Pons Aelius, as may the columns from the tract of the Via Tecta situated between the intersection with the Via del Banco Santo Spirito and the Pons Neronianus, which had become a blind alley with the closure of the bridge (Figure 3.1).20

Figure 3.1 The western Campus Martius in Rome, with the route of the porticus maximae to the Pons Aelius and the arch of Valentinian, Valens and Gratian.

While this last point may be considered speculative, it is clear that the road leading to the Pons Aelius did indeed come to be flanked by impressive porticoes, which seem to have been installed, apparently for the first time, in the later fourth century. The key piece of evidence is the lost inscription from the triumphal arch of Valentinian, Valens and Gratian, completed ca. 380 athwart the southern approaches to the Pons Aelius, which survives in a ninth-century transcription: ‘Our lords, emperors and caesars Gratian, Valentinian and Theodosius, pious, fortunate and eternal augusti, commanded that (this) arch to conclude the whole project of the porticus maximae of their eternal name be built and adorned with their own money.’21 In addition to providing a firm date for the arch, the inscription strongly implies that the porticus maximae, which must refer to porticoes along the street leading to the arch, was realized in connection with, or shortly before, the arch itself, in what was clearly perceived as a unified architectural scheme, for which the arch served as the final and concluding element (arcum ad concludendum opus omne porticuum maximarum). The best conclusion is that the new porticoes extended the existing colonnades of the Via Tecta along the stretch of road leading to the only surviving river crossing in the area, which in turn provided access to St. Peter’s, one of the crucial nodes in Rome’s emerging Christian topography.22

The centrality of St. Peter’s in the spiritual and ceremonial life of Rome was further accentuated by the construction of an additional covered colonnade on the far side of the Tiber, flanking the road leading from the mausoleum of Hadrian to the church. While it is first securely attested in the Gothic War of Procopius, written in the mid-sixth century, the colonnade was likely built rather earlier, perhaps indeed shortly after or in connection with the porticus maximae, to which it would effectively have formed the extra-urban continuation, creating a nearly continuous colonnaded panorama stretching all the way from the Via Tecta in the intramural heart of the city, via the new arch of Valentinian, Valens and Gratian and the Pons Aelius, all the way to the Vatican.23

The other two most substantial street porticoes erected in late antique Rome led from the Porta Ostiensis in the Aurelian Wall along the Via Ostiensis to the church of St. Paul’s outside the walls; and from the Porta Tiburtina along the Via Tiburtina to the basilica of San Lorenzo. While they too are only known from later sources (of the mid-sixth and eighth centuries, respectively),24 both structures may well date as early as the later fourth century. They likely belong to approximately the same period as the portico leading to St. Peter’s, as the similarities in form and function common to all three suggest that they were conceived as interrelated parts of a unitary architectural scheme designed to connect the suburban shrines of Rome’s three most venerated martyrs with the Aurelian Wall, and thus with the city center. In the case of the portico to St. Paul’s, a date in the 380s appears especially likely, as it was in precisely this period (beginning in ca. 383–84) that the Constantinian church on the site was replaced by a massive new basilica sponsored by Valentinian II,25 the same Western emperor under whom, it should be remembered, the triumphal arch and the porticus maximae leading to the Pons Aelius were erected. It is surely as good a hypothesis as any that the imperial authorities, presumably working in concert with Pope Damasus (366–84), sought to monumentalize the route to the new St. Paul’s and link the church to the city center during or soon after its construction, by means of an imposing portico that mirrored the extra-mural extension of the porticus maximae leading to St. Peter’s. Damasus, of course, is best known for his tireless efforts to restore and popularize the suburban shrines of Rome’s leading martyrs,26 whence the temptation grows powerful to imagine that he actively collaborated in a scheme to anchor the devotional circuit of the Roman periphery he did so much to promote on three porticated ‘access roads’ leading to the shrines of Rome’s three greatest martyrs.

By the sixth century, when the annual liturgical calendar of the Roman church was largely complete, the three churches of St. Peter’s, St. Paul’s and San Lorenzo remained the only extramural shrines regularly visited by the popes in the course of the stational processions that increasingly came to define the sacred topography of the city.27 The porticated avenues thus provided a grandiose architectural framework for the ceremonial processions led by the popes to the three great extramural sanctuaries in the course of the annual liturgical cycle.28 The prominence of these processional routes in the topographical horizons of the city and the ideological agendas of its bishops was such that they continued to be maintained for centuries, often at enormous cost. In the late eighth century, Pope Hadrian I (772–95) restored all three porticoes, in the case of the route to St. Peter’s allegedly by reusing 12,000 tufa blocks taken from the embankments of the Tiber to complete the project.29

But while the popes may have been unusually successful in preserving the grand processional ways marked out in Rome in late antiquity into the early Middle Ages, similar porticoes once dominated the cityscapes of other Western capitals in late antiquity, notably those that superseded Rome as preferred imperial residences.

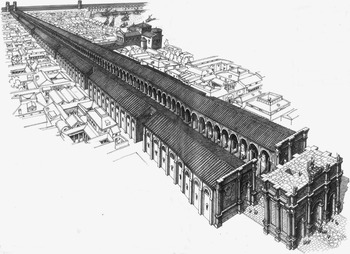

In Italy, Milan served as the primary seat of government from 286 until 402, during which time it too saw the erection of an architecturally prepossessing porticated avenue. As excavations undertaken in the 1980s during the construction of the MM3 underground line demonstrated, the new street took shape in ca. 375–80, and thus at almost exactly the moment when the porticus maximae at Rome were built, under the patronage of the same Italian emperor, Valentinian II. The Milanese porticoes were two stories high, and extended for nearly 600m along both sides of the road leading to Rome, beginning from the Porta Romana in the circuit-wall and terminating, again like the Roman exemplar, with a triumphal arch.30 Moreover, just as at Rome, the colonnades were linked to an especially prominent extramural church, the new Basilica Apostolorum built by Bishop Ambrose between 382 and 386 at the midway point of the newly aggrandized street (Figure 3.2).31 In light of the new evidence for dating the porticoes scant years before the appearance of the church, there is now better reason than ever to imagine – as past scholars operating under the assumption that the rebuilt street dated to the third century were already tempted to do32 – that the proximity of the imperial triumphal way was a determining factor in Ambrose’s decision to situate the first and most prestigious of his three (or four) great extramural churches adjacent to its porticoes.33 In so doing, Ambrose – surely consciously – reproduced the topographical relationship between St. Peter’s and the Via Triumphalis at Rome, and also, as we shall see, between a principal Constantinopolitan triumphal avenue and the city’s own church of the apostles, the Apostoleion, whose unusual cross-shaped plan directly inspired the cruciform layout of the Ambrosian Basilica Apostolorum.34 So too at Trier, the east end of the cathedral – suggestively dedicated to St. Peter and rebuilt under Valentinian and Gratian (364–83) – featured a twelve-sided aedicula enclosed within a massive square precinct, another Apostoleion in miniature that was, moreover, directly accessible from the porticated cardo departing from the Porta Nigra.35 In each case, we see civil and ecclesiastical authorities effectively collaborating in the creation of new, monumental urban itineraries, punctuated by imperially sponsored street porticoes, triumphal arches and city gates that provided a suitably grandiose setting for the formal processions that dominated the ceremonial repertoire of both church and state.36

Figure 3.2 Milan: the via Romana colonnades and the Basilica Apostolorum.

The dedication of the Milanese church of the Apostles on May 9, 386 culminated with the translation and installation under the high altar of the relics of John the Baptist and the Apostles Andrew and Thomas, doubtless conveyed to the church in a festive procession along the Via Romana arcades.37 The event indeed left such an impression on the Christian faithful that when Ambrose later consecrated the Basilica Ambrosiana, the assembled crowd loudly demanded that he consecrate the new church with relics, as he had the basilica in Romana.38 The Basilica Apostolorum, that is, derived its vulgar name from the porticated (via) Romana whence it was accessed, which in the popular imagination – as well as in material reality – was inextricably connected with the church itself, as was the memory of the relic procession that accompanied its dedication. Motivated by the prompting of the crowd, Ambrose exhumed the bones of the local martyrs Gervasius and Protasius, which he conveyed to the Ambrosiana in a triumphal procession directly inspired by the protocols governing secular adventus.39 Nine years later, when Ambrose sought to exalt the remains of Nazarius, another local martyr, he sent them to the extramural church best architecturally equipped, by virtue of its monumental access road, to host yet another triumphal entry of relics: the basilica in Romana – Basilica Apostolorum, thereafter known also as S. Nazaro.40

The chronology of the monumental porticoes built along the approaches to several of the leading churches in Rome and Milan in the 380s is particularly noteworthy given that evidence of imperial participation in processions held to mark the translation of relics begins with the reign of Theodosius I (379–95).41 According to Sozomen, in 391 Theodosius solemnly carried the head of John the Baptist to his new church dedicated in the martyr’s name, located outside the Golden Gate at the Hebdomon, the same place from which newly raised emperors departed on their ceremonial entrance into Constantinople.42 In 406, Theodosius’ son Arcadius joined the Patriarch of Constantinople and members of the Senate in transporting the relics of Samuel into the city.43 In 411, these relics were deposited outside the new city walls at the church of St. John iucundianae at the Hebdomon, which took its name from the imperial palace of the same name located nearby.44 During the reign of Theodosius II (408–50), the emperor and members of the imperial family regularly participated in translations of relics, as when, in 421, the remains of Stephen were paraded through the city, in a style befitting of an imperial adventus, on their way to their final resting place at the oratory of St. Stephen, newly built inside the imperial palace itself, at the eastern extremity of the Mese, the main processional artery in the city.45 With the installation of the relics of both John the Baptist and Samuel at the Hebdomon, and those of Stephen at the palace inside the city, the starting and ending points of the imperial triumphal route along the Mese were bracketed by collections of newly installed relics, in the translation of which the imperial family had, moreover, actively participated. At San Nazaro, meanwhile, the relics of the eponymous martyr were ensconced in a chapel decorated with Libyan marble at the behest of the magister militum Stilicho’s wife, Serena, who prayed for her husband’s safe return from campaigning in the dedicatory inscription.46 Thus, at Milan, too, the church that seems to have become the preferred stage for the display of court-sponsored patronage of the cult of relics was the one most closely connected with the monumental route (the very road, perhaps, along which Serena hoped to see her husband return in triumph?) followed by imperial processions.

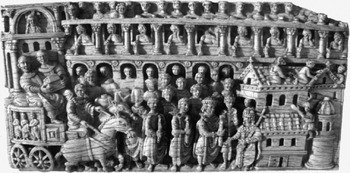

Beginning in the later fourth century, then, the rulers of the empire were evidently increasingly eager to link their public personae with the triumphs of the Christian church, and they actively collaborated with church leaders in the celebration, veneration and architectural framing of the martyrs who, in triumphing over death, had preserved orthodoxy and placed the Christian Roman empire over which they presided under divine protection.47 Ambrose himself, like many of his contemporaries, leaves no doubt that the arrival of relics was a triumphal occasion, best presented in the trappings of triumphal imperial adventus that would have been immediately familiar to the inhabitants of any imperial capital.48 Enthroned on the four-wheeled cart (plaustrum) used to convey arriving emperors in the fourth century, preceded by torches and standards, and hailed by the acclamations of the masses, the bones of the illustrious Christian dead were greeted with reverence otherwise reserved for reigning emperors.49 The transfer of relics to churches connected to the principal porticated streets of a late antique capital such as Milan could subsequently unfold in the same spaces used by the emperors for their own triumphal arrivals: a church procession through the porticoes of the Via Romana would inevitably have called to mind imperial processions along the same street. The connection between imperial and ecclesiastical ceremony thus received its definitive and lasting stamp in the realm of architectural space, in the form of a monumental processional way jointly exploited by civic luminaries and bishops. When the emperors themselves participated in translations of relics, the circle was closed: state and church triumphed together, as the representatives of each basked in the reflected glow of their counterparts. The imperial presence ennobled the ecclesiastical ceremony and proclaimed the unity of bishops and Christian sovereigns in the governance of the empire. The emperors themselves grew in the eyes of the Christian faithful, as the patrons and colleagues of the holy men tasked with stewarding the bones of the martyrs and mediating the access of the faithful to this most precious of all forms of spiritual currency.

3.3 Constantinople

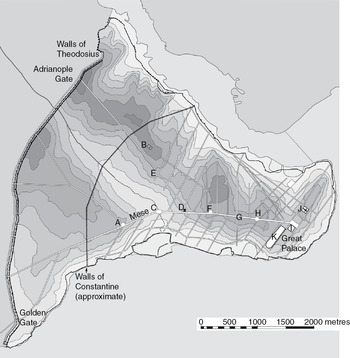

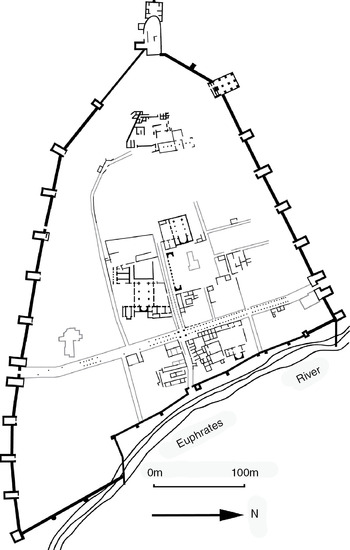

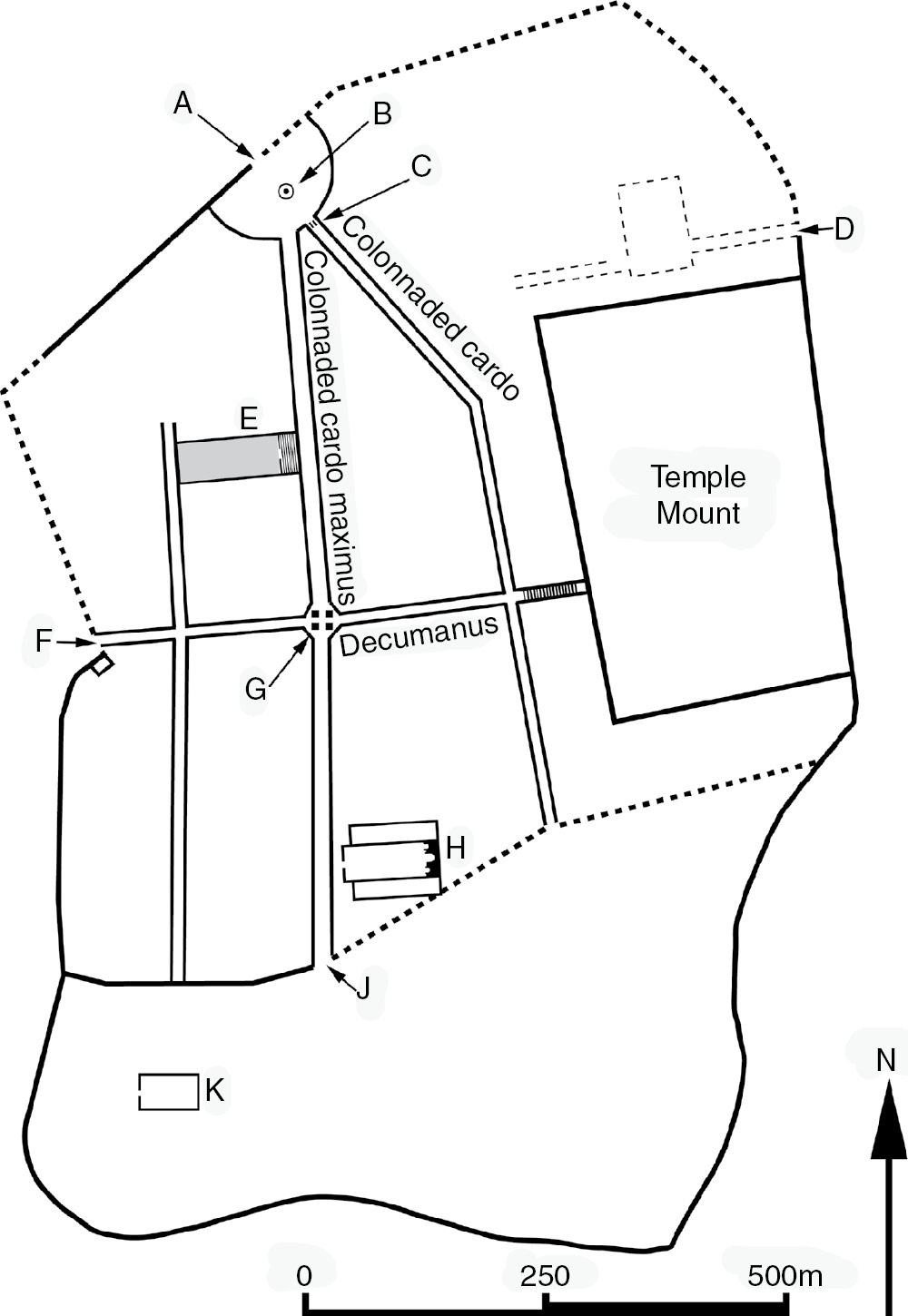

The topographical nexus between imperial and ecclesiastical authority was nowhere more fully realized than in Constantinople, the ideal laboratory for the testing and elaboration of the urban paradigm envisioned by the first generations of Christian emperors. Officially inaugurated on May 11, 330, the birthday of its founder and namesake, the new city afforded Constantine and his successors in the fourth and fifth centuries a sort of architectural blank slate, onto which they were free to delineate an ideal vision of an imperial capital, largely unencumbered by the constraints of preexisting urban topography. In Constantine’s day, the new city center, built over and around the much smaller existing town of Byzantium, gravitated around an architectural core based on a single colonnaded main street, the Mese, that comprised the final tract of the principal land route leading to the city from Greece and the West, the Via Egnatia (Figure 3.3).50 After traversing the Golden Gate in the new land walls, the visitor approaching from the west arrived first at the Capitol – prime symbol of the ‘old’ Rome and so too of Constantine’s ‘new’ Rome51 – and the nearby precinct of the Philadelphion, a colonnaded square filled with statues and commemorative monuments to the emperors (among them the porphyry Tetrarchs now in Venice).52 From the Philadelphion, the Mese continued to the east, lined with majestic two-story colonnades, as far as the circular forum of Constantine, itself surrounded by colonnades two stories high, and graced at its center by a porphyry column topped by a gilded statue of Constantine.53

Figure 3.3 Constantinople. A: Forum of Arcadius; B: Apostoleion; C: Forum of the Ox/forum bovis; D: Philadelphion; E: Forum/column of Marcian; F: Forum of Theodosius; G: tetrapylon; H: Forum of Constantine; I: Baths of Zeuxippos; J. Hagia Sophia; K: hippodrome.

The two-story colonnades of the Mese thence continued east toward the milion, the Constantinopolitan equivalent of the umbilicus in the Roman Forum, marked by a monumental arch, likely a quadrifrons, spanning the street, just behind which stood a statue of an elephant, the very symbol of imperial triumph that adorned the quadrifrons arch at Antioch.54 To the north and south, the colonnades of a second avenue running perpendicular to the Mese converged on the archway, which thus stood, as at Antioch, Thessaloniki and Split, at the intersection of four radiating colonnaded axes, the shortest of which – again – led straight to the palace. This final stretch of the Mese, now wider and grander still and called – again – the Regia, stretched eastward from the milion to the main gate of the palace, known by the fifth century as the Chalke.55 The form of the gate appears to have been rectangular, with a domed central chamber straddling the axis of the Regia and two lower flanking bays, very much like the Arch of Galerius at Thessaloniki.56 North of the Regia stood the Augusteion, a colonnaded square flanked by a second senate house, joined under Constantius II (337–61) by the cathedral of Hagia Sophia and the palace of the patriarchs along its northern extremity.57 The Constantinian cathedral of the city, Hagia Eirene, lay just beyond to the northeast.58 To the south, the southern colonnade of the Regia gave onto the Baths of Zeuxippos and the carceres of the hippodrome, both rebuilt by Constantine and directly connected to the imperial palace itself, which sprawled south and east toward the shores of the Sea of Marmara (Figure 3.4).59

Figure 3.4 The area of the Great Palace in Constantinople. A: Hagia Eirene; B: Hagia Sophia; C: Augusteion; D: Mese; E: Milion; F: Chalke Gate; G: Baths of Zeuxippos; H: hippodrome; I: pulvinar; J: Peristyle Court; K: Yerebatan cistern; L: Palace of Lausos.

While the archaeological evidence is scanty and leaves infinite scope for haggling over the details, the basic contours of the palatial quarter in Constantinople as it took shape beginning under Constantine are clear enough.60 The complex gravitated around the Regia, itself framed at the west by the milion and at the east by the principal gate of the palace, the Chalke. The hippodrome and the greatest baths in the city (of Zeuxippos) stood just off the Regia, in the immediate vicinity of the entrance to the palace, and both in fact communicated directly with the palace to the rear, while their public entrances lay just off the colonnades of the street.61 By the fifth century (and probably earlier), the palace was also bodily attached to the cathedral of Hagia Sophia, via – yet another – colonnaded passageway, an elevated loggia by the sixth century, which connected the northern bay of the Chalke with the south flank of the church.62 Baths, hippodrome, arches, the imperial palace and the cathedral, all linked by the armature of a single, extraordinarily grandiose colonnaded avenue and further colonnaded extensions thereof: it is the culmination of the ‘imperial’ architectural paradigm that took shape in the third century, a cohesive ensemble that need not have exactly ‘copied’ any existing foundation to nonetheless reprise the essential features of all the imperial capitals and residences discussed in the preceding chapter, insofar as these can be known or surmised on the basis of the available evidence.

Later sources are surely right to suggest that already at the time of the dedication of the new capital in 330, the Mese with its associated monuments was conceived as a grand triumphal route. According to the eighth-century Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai, the founding ceremony on May 11 witnessed the transfer of a gilded statue of Constantine from the Capitol to the forum of Constantine, where it was laboriously raised, in front of the assembled people and dignitaries of the new city, up to its final resting place atop the porphyry column.63 In the words of Franz Alto Bauer, ‘The transfer of the statue to its new location appears to have been staged as a triumphal entry of the emperor into the city. An escort wearing white chlamydes, holding candles, accompanied the statue, which stood erect in a chariot, from the Philadelphion to the Forum of Constantine. Thus was staged the adventus of the emperor who, present in his statue, proceeded along the main street of Constantinople and finally reached “his” forum.’64

But while the transfer of the statue to the column was a one-time event, Constantine also made provision for a more lasting commemorative adventus, to be staged every year on the occasion of his birthday and the founding of the city. Again, the protagonist was (yet another) gilded statue of the emperor, ordinarily kept in a repository on the north side of the forum of Constantine, which every May 11 left the forum mounted on a triumphal chariot and processed down the Mese and into the hippodrome, where it made a lap of the track and came to rest in front of the imperial box (kathisma) to receive the obeisance of the reigning emperor.65 ‘By means of this ritual, therefore, the memory of the founding emperor was awakened in the consciousness of the populace; gilded, like the statue on the porphyry column ... He received the acclamation of the populace, the aristocracy and the emperor, before returning to the Forum of Constantine.’66

For more than a century following the death of Constantine in 337, succeeding emperors made it their task to extend the monumental framework of the Mese with a series of imperial forums and triumphal monuments arrayed along the main axis of the street. Theodosius I (379–95) built his forum between the forum of Constantine and the Capitol; the forum of Arcadius (395–408) took shape still farther to the east; and that of Theodosius II (408–50) rose between the old Constantinian walls and the new land walls of the city, built between 405 and 413.67 There, the road exited the city via the Porta Aurea, much the most magnificent gate in the new circuit, which took the shape of a triumphal arch dedicated to Theodosius II.68 New colonnades rose along the Mese in correspondence with the new forums, linking them all together in an unbroken progression of symbolically charged spaces designed to exalt the memory of their individual founders and propagate the timeless ideology of imperial victory upon which their claims to legitimacy and unchallenged sovereignty rested.69

At the Philadelphion, the main tract of the Mese on its way to the Porta Aurea diverged from a second colonnaded avenue, which angled northwest toward the Charisios (or Adrianople) Gate in the Theodosian walls. The centrality of this northern branch of the Mese in the landscape of the new city had been proclaimed already under Constantine himself, who erected his mausoleum just to the north of the road shortly before it traversed the Constantinian walls.70 The mausoleum, final resting place of the emperors through the reign of Anastastius I (d. 518),71 was flanked by the cruciform church of the apostles, the Apostoleion, probably begun in the 350s by Constantius and consecrated in 370.72 The fame of this church was such that Ambrose based the cruciform plan of his own Basilica Apostolorum at Milan on the Constantinopolitan exemplar;73 and the location of Ambrose’s church at the midway point of the Porta Romana colonnade strongly implies that the Milanese bishop was attempting more broadly to replicate the architectonic context of the Apostoleion and to ensure that his new foundation was similarly privileged by virtue of its physical proximity to the main ceremonial thoroughfare of the city.

In the mid-fifth century, when all of the prime locations along the southern branch of the Mese had been occupied by imperial monuments, the emperor Marcian (450–57) was compelled to establish his own forum along the northern extension of the Mese, between the Philadelphion and the Apostoleion.74 Thus, by the time of Marcian’s death, the architectonic imprint of the capital was largely complete. The most magnificent public buildings and forums in the city, as well as the churches of Hagia Sophia, Hagia Eirene and the Apostoleion, were either bisected by or proximate to the trunk of the Mese in the east and its two principal continuations in the west.75 These expansive, colonnaded thoroughfares were the spinal cord of the city as a whole, the architectural profile that imprinted itself on the consciousness of visitors and residents alike, and the repositories of the institutional memory encoded in their flanking monuments. The Mese anchored the ceremonial processions that gave tangible form to the ascendancy of Constantinople’s civic and ecclesiastical authorities, and at the same time channeled the flow of quotidian life and commerce through the most ideologically charged spaces in the city, the forums and commemorative columns bedecked with statues, reliefs and inscriptions that inevitably called to mind the mighty who had commissioned them, and who animated them on important occasions with their superhuman presence.76

When newly crowned emperors made their triumphal entrance into the city, as Leo I did in 457, or returned from extended absences, as Justinian did in 559, the entire population of the city, arranged sequentially and hierarchically according to rank and station, lined these streets and chanted their acclamations to the passing imperial cortege. On the most important days in the annual liturgical calendar, ecclesiastical processions followed the same route on their way to the leading shrines in the city.77 When relics arrived, such as those of Samuel in 406, Stephen in 421, and John Chrysostom in 438, these too made their adventus into the city along the Mese and its northern and southern extensions, conveyed in regal splendor by patriarchs and reigning emperors, whose joint participation in these processions ostentatiously proclaimed the ideal unity of church and state in a polity in which these two institutions grew ever more inseparable.78

Already in ca. 400, the presence of the emperor Arcadius and his wife Eudoxia featured prominently in the sermon John Chrysostom delivered upon the arrival of the relics of the Pontic martyr Phocas to Constantinople, in which, moreover, the physical essence of the city was distilled into a vision of its grand colonnades: ‘The city became splendid yesterday, splendid and illustrious, not because it has columns, but because it hosted the parade of the arriving martyr, who came to us from Pontus.’79 The newly arrived relics may have glorified the city as the colonnades alone never could have, but it was nonetheless the image of the colonnaded street that provided, in the mind of the bishop, the essential architectural backdrop for the solemn festivities that bound Arcadius and Eudoxia together with the clergy and the urban masses in joint veneration of Phocas’ mortal remains.80

3.4 Porticated Streets and the Literary Image of Late Antique Cityscapes

One of the great strengths of porticated streets was their capacity to channel the flow of both quotidian and ceremonial life within their confines: to direct movement along a limited number of privileged itineraries designed to highlight key civic monuments and connect them with grand colonnaded façades in a seamless topographical ensemble. The scattered civic monuments of the high imperial period, many of them falling into disrepair, and the teeming residential neighborhoods of the lower classes could be selectively filtered from view behind the lofty screens of porticoes lining the main streets of the late antique city. The testimony of contemporaries writing in the fourth and fifth centuries indicates that the urban experience was increasingly coming to be distilled into the visual and spatial parameters delineated by porticated avenues, which had become the essence of urban grandeur, the token by which a great city could be recognized and most succinctly defined.

One such indicator comes from the Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, the extensive catalogue of urban topography in Constantinople compiled by an anonymous author writing ca. 425. While street colonnades are punctiliously listed in all of the fourteen chapters devoted to the various regions of the city, particularly evocative is the description of the seventh region, located in the ceremonial heart of the city, extending north from the Mese, between the forum of Theodosius and the forum of Constantine, as far as the shores of the Golden Horn. The summary description of the region that precedes the detailed listing of its component structures reads thus in its entirety:

In comparison to the previous one, the seventh region is flatter, though it too on its far extremity slopes steeply to the sea. From the right side of the column of Constantine all the way to the forum of Theodosius, it extends flanked by continuous colonnades, with other similar colonnades extending along the side streets, and continues, leaning downward as it were, all the way to the sea.81

For all that the seventh region was populous and densely built, it is the colonnaded sweep of the Mese between the forums of Constantine and Theodosius I, with its colonnaded cross-streets, that dominates the topographical panorama sketched by the author, and shapes the visual profile of the region as a whole. Visitors and residents alike might traverse the entirety of this central district of the capital without experiencing it as anything other than a continuous succession of stately colonnaded façades; the glorious illusion would give way to a more jumbled and heterogeneous reality only for those whose business carried them beyond the main roads.82

In his list of the twenty greatest cities of the empire, written ca. 380, Ausonius includes a similarly succinct description of the city of Milan, which concludes with reference to ‘her colonnades (peristyla) all adorned with marble statuary, her walls piled like an earthen rampart around the city’s edge.’83 The juxtaposition between city wall and colonnades is particularly striking, as it was the gates in the wall that framed the principal streets in the city, including the Via Romana with its grand new arcades, themselves under construction or very recently completed at the time when Ausonius was writing. For the visitor approaching from the south, Milan will indeed have been experienced precisely as the intersection of the porticated street and the city wall, which between them channeled the flow of traffic onto a single axis and screened from view all of the less monumental quarters of the city.

The predominance of porticated vistas in the imagination of late antique writers appears to herald a real shift in prevailing views, or mental images, of urban topography, for all that a similar inclination to condense the essence of urban civilization into colonnaded streets occasionally occurs earlier, notably in Achilles Tatius’ second-century description of Alexandria.84 In his lament for the martyrs of the Diocletianic persecution in Palestine in 309, Eusebius turns the morning dew on the colonnades of Caesarea into tears of sorrow wept by the city for its fallen: ‘The air was clear and bright and the appearance of the sky most serene, when suddenly throughout the city from the pillars which supported the public colonnades (stoai) many drops fell like tears; and the marketplaces and streets (agorai te kai plateiai), though there was no mist in the air, were moistened with sprinkled water.’85 For Eusebius, the columns of the street colonnades were evidently the most pervasive and characteristic feature of the cityscape, the architectural element best suited to express the mourning of the entire city: they were the eyes and the wounded heart of Caesarea personified. So too in the mind of the anonymous mid-fourth-century author of the Expositio totius mundi et gentium, the grandeur of Carthage is apparent in its regular grid of streets, which in their ordered symmetry called to his mind the image of an orchard.86 The columns lining the streets make the metaphor: in the urban orchard of Carthage, the rows of columns take the place of trees as the dominant visual element. Likewise in the imagination of John Chrysostom, as we have seen, the columns of Constantinople became a synecdoche for the architectural grandeur of the city as a whole.87

But by far the longest and most explicit surviving account of the place of colonnaded streets in the physical, social and mental geographies of the late antique metropolis comes in Libanius’ Oration 11, the Antiochikos.88 The text concludes with a topographical excursus on the city that runs to some ten pages in Downey’s edition, nearly half of which centers on the form, the beauty, and the function of the city’s colonnaded avenues, its grand central axis above all.

(196) And now it is the proper time to describe the situation and size of the city, for I think that there can be found none of those which now exist which possesses such size with such a fair situation. Beginning from the east it stretches out straight to the west, extending a double line of stoas. These are divided from each other by a street, open to the sky, which is paved over the whole of its width between the stoas ... (201) The stoas have the appearance of rivers which flow for the greatest distance through the city, while the side streets seem like canals drawn from them ... (212) As you go through these stoas, private houses are numerous, but everywhere public buildings find a place among private ones, both temples and baths, at such a distance from each other that each section of the city has them near at hand for use, and all of them have their entrances on the stoas.89

For Libanius, Antioch is a great city above all because of its colonnaded streets, which are both beautiful and the essence of civic life.90 The main street is quite literally the architectural centerpiece of the city, the conduit that in turn leads to its grandest public buildings, all directly accessible from its flanking colonnades.

Nor was Libanius alone in judging Antioch’s wide, colonnaded streets the epitome of its urban glory. When John Chrysostom was still a priest at Antioch, he delivered a sermon during the ‘affair of the statues’ in 387, while the Antiochenes were anticipating with dread Theodosius’ response to their destruction of imperial images near the palace on the Orontes. In what was almost certainly a conscious evocation of his despised former teacher Libanius’ Antiochikos, Chrysostom pointed out to his congregation that the true beauty of their city, whatever became of it as a result of the emperor’s wrath, lay not in its wide, colonnaded streets, but rather in the virtue and piety of its (Christian) inhabitants.91 As with his later sermon on the arrival of Phokas’ relics at Constantinople, what Chrysostom’s effort to subordinate colonnaded streets to the greater glories of the Christian faith really shows is just how synonymous these streets had become, by the later fourth century, with the concept, the idea and the reality, of a leading Mediterranean metropolis.

But to return to Libanius, his lengthy encomium is also noteworthy for being the only extant account that makes a concerted effort to explain why colonnaded streets were so central to the configuration of the ideal cityscape:

(213) What then is my purpose in this? And the lengthening of my discourse, entirely about stoas, to what end will it bring us? It seems to me that one of the most pleasing things in cities, and I might add one of the most useful, is meetings with other people. That indeed is a city, where there is much of this ... (216) while the year takes its changes from the seasons, association is not altered by any season, but the rain beats upon the roofs, and we, walking about in the stoas at our ease, sit together where we wish.92

Rather than treating them only as essential elements of urban décor, that is, Libanius considered the stoai of Antioch in terms of their functionality; of the uses to which they were put, and the activities that unfolded within and around them.

In addition to keeping the winter rains off the Antiochenes and allowing all members of the urban collective to mingle and conduct business even in the depths of winter, Libanius’ colonnades were the teeming commercial heart of the city, packed with industrious craftsmen and vendors who filled the spaces between the columns and spilled out onto the street:

(254) The cities which we know pride themselves especially on their wealth exhibit only one row of goods for sale, that which lies before the buildings, but between the columns of the stoas no one works; with us, however, even these spaces are turned into shops, so that there is a workshop facing almost each one of the buildings.93

His words are a valuable reminder that colonnaded streets were lived space, fulcrums of everyday living, as much as settings for grand displays on special occasions. Antioch’s main roads were both beautiful and bustling, grand architectonic vistas and the center of daily life. Here is the death knell for attempts to apply Sauvaget’s vision of the ‘devolution’ of the colonnaded street into the suq to the end of antiquity:94 long before the alleged disintegration of effective civic government and the ‘privatization’ of public spaces in the sixth century, the colonnaded thoroughfares of the great cities of the eastern Mediterranean already teemed with shops and commercial activity.95 Indeed, it was their mundane role as much as their ceremonial profile that made such streets so desirable in late antiquity, and led them to become more prominent than ever before on the urban landscape.

3.5 Commerce, Commemoration and Ceremony in the Colonnades of the Eastern Mediterranean

Even if Libanius’ hyperbolic assertion that Antioch was unique for the amount of activity in its colonnades were true, his depiction of the throng of shops filling the intercolumniations of Antioch’s main streets would be nonetheless noteworthy. Antioch was the capital of the diocese of Oriens and seat of both the Praetorian Prefect of the East and the comes orientis, a place where the reach of the imperial administration and the ceremonial regime governing the public deportment of high officials were particularly robust.96 A perusal of Libanius’ voluminous corpus suggests that work on street colonnades at Antioch was almost the exclusive preserve of ranking members of the imperial administration, chiefly serving governors or ex-governors of proconsular rank resident in the city, who in fact seem to have made colonnaded streets their first priority in the realm of public building.97 The crucial point is that, their immense prestige value aside,98 these colonnades were envisioned from their inception as grand commercial arcades, useful for producing revenues for the imperial servants who built them as well as ennobling the spaces where they paraded about. When the ex-governor Florentius widened a street and lined it with a colonnade in 392, he expected to recoup his costs (and far more, according to the hostile Libanius) from the rents of the shops located behind the columnar façade.99 When the provincial governor Tissamenes had a street colonnade repainted (!), he rewarded the painters and defrayed his own costs by compelling the commercial tenants of the structure to have their shop signs done by the same painters, presumably at substantial cost.100 Far from a symptom of the collapse of effective civic authority, then, the ‘encroachment’ of commercial activities on the public colonnades of Antioch is better construed as an indicator not only of economic vitality, but also of the immense power and local influence of the imperial representatives who built and maintained the colonnades. It is also a sure sign that there was no profound incompatibility between the dual roles of Antioch’s stoas as lived space on the one hand, and ceremonial space on the other.

Further, it turns out that the situation in Antioch was far less anomalous than Libanius would have us believe. Both archaeological and textual evidence makes it clear that in other provincial and imperial capitals in the eastern Mediterranean, the colonnades of the main streets were similarly packed with vendors’ stalls and workshops, and continued nonetheless to preserve the monumental profile upon which their role as privileged theaters of ceremonial life depended.101 In the fifth century, we find the central administration in Constantinople legislating with the express intent of reconciling the exigencies of commerce with the equally pressing need to maintain the architectural decorum of the Mese: a decree addressed by the emperor Zeno to Adamantius, praefectus urbi of Constantinople in 474–79, prescribes in minute detail the proper configuration of shops along the colonnades of the Mese, from the milion at its eastern extremity as far as the Capitolium.102 The façades of the intercolumnar stalls were to be no more than six feet wide and seven high, and to be revetted with marble on their exterior facings, ‘that they may be an adornment for the city and a source of pleasure for passersby.’103 Zeno’s special concern for the principal ceremonial avenue in the city, the route indelibly associated with his public appearances, is manifest in the further specification that the disposition of shops in all other city colonnades fell under the purview of the city prefect.104 The décor of the city’s ‘imperial’ street alone required the direct supervision of the emperor himself. Archaeology reveals that similar aesthetic concerns prevailed at Ephesus, where the shop fronts installed in the intercolumnations of the main processional way (the Embolos) were covered with marble veneer on their external facings in the fifth and sixth centuries.105

Ephesus in fact provides, I would suggest, the closest thing possible to a canonical example of the intertwining of social and economic imperatives with ceremonial agendas in the topographical evolution of a late antique metropolis in the eastern Mediterranean. Capital of the diocese of Asia after Diocletian and later seat of a metropolitan bishop, it is one of the best excavated and most thoroughly studied of the empire’s leading cities. Its extant remains furnish an unusually detailed perspective on the evolving patterns of human activity, and even of the changed mentalités underlying them, that so profoundly conditioned the physical parameters of the urban environment and imbued them with their characteristically late antique features, chief among them a colonnaded street and its associated monuments.

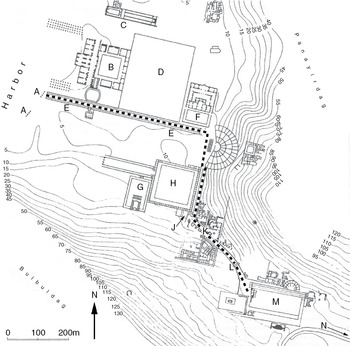

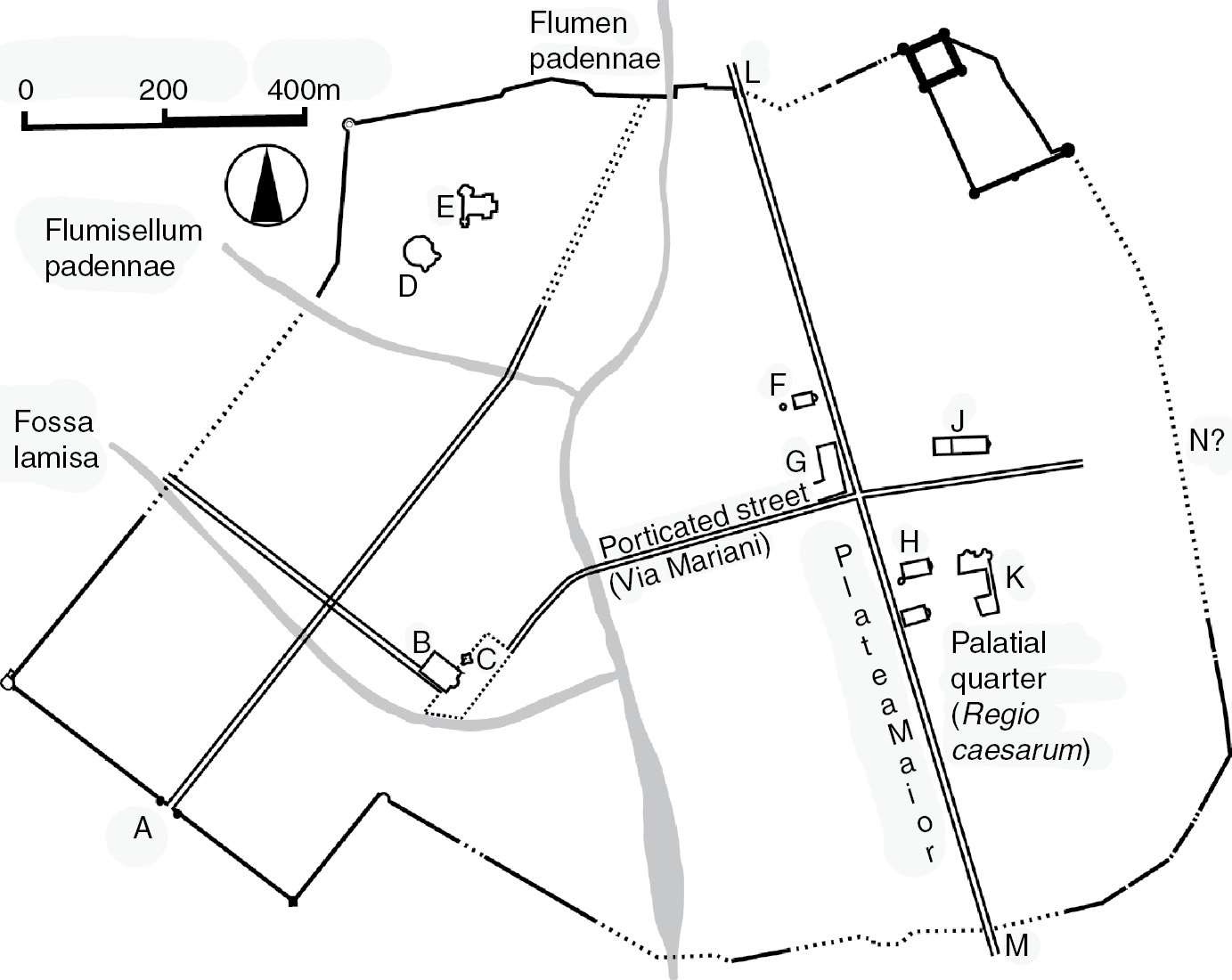

Between the fourth century and the seventh, the city gravitated ever more closely around a single main street, composed of three intersecting segments on different orientations, flanked along nearly all of its length by colonnades built in the fourth and fifth centuries (Figure 3.5). Throughout this period, the majority of investment in public architecture and urban infrastructure occurred in the environs of this central axis, beginning with the paving and colonnades of the road itself, and extending to the public monuments – squares, triumphal arches and columnar monuments, nymphaea, the theater – and the opulent private houses that lined its course.106 Those approaching the city center from the direction of the harbor (as most distinguished visitors arriving from afar will have done) first embarked on the Arkadiane, the wide, straight promenade between the harbor and the theater, which was monumentally re-edified ca. 400 with 600 meters of continuous colonnades along both sides of the street, sponsored by Emperor Arcadius, from whom it took its name.107 A sharp right at the theater led to the ‘Marble Street,’ running past the scaena of the theater and the lower agora and on to the old library of Celsus, rebuilt as a grand nymphaeum, also ca. 400; there, the road turned sharply again to become the Embolos (or ‘Curetes Street’), leading upward from the façade of the nymphaeum toward the upper agora, beyond which lay the principal gate in the land walls, the Magnesian Gate (Figure 3.6).108 As with the Arkadiane, the Marble Street and the Embolos were maintained in grand style into the early seventh century: the solid pavers of the roadbed were kept whole and unobstructed, the colonnades assiduously restored whenever necessary, the floors of the covered sidewalks repaved with new mosaics and sumptuous marble panels, the shop fronts revetted with marble.109

Figure 3.5 Central Ephesus in late antiquity. A: Harbor-Gate; B: Baths of Constantius; C: Church of Mary; D: palace; E: Arkadiane; F: Theater Gymnasium; G: Temple of Serapis; H: Lower Agora; J: Library of Celsus; K: Embolos; L: Gate of Herakles; M: Upper Agora; N: to Magnesian Gate. Dotted line marks course of the Arkadiane-Embolos route.

Figure 3.6 The Embolos today.

This continuous monumental armature comprising the three sections of the road and its associated structures attained unprecedented heights of architectural grandeur, beginning in the fourth century, because the governors who thenceforth controlled the funds available for building chose to make it the architectural showpiece of the city as a whole, and to recognize its de facto role as the epicenter of civic life. As Franz-Alto Bauer has shown, by the fifth century, the Arkadiane–Marble Street–Embolos axis had largely supplanted traditional civic spaces, such as the upper and lower agorai, as the venue of choice for the display of statues and inscriptions honoring the leading patrons and benefactors of the city and the late Roman state.110 City councilors and private euergetes are almost nonexistent: the dedicatees of the dozens of fourth-to-sixth-century statues and inscribed bases found among the colonnades and along the street overwhelmingly represent the emperors and members of the imperial family on the one hand, and governors and other representatives of the central administration on the other.111 This is of course to be expected, given that imperial agents were chiefly responsible for the upkeep of public architecture and infrastructure from the fourth century on.112 What is remarkable is the extent to which the colonnades and other monuments flanking the road were preferred to all other buildings in the city for the display of honorary monuments. That they were so privileged strongly suggests that there was no better place to be honored and immortalized for posterity, and thus that the city’s main processional avenue had become the heart of the urban collective, the place where the images of the emperors and their local delegates were most effectively brought before the eyes of the urban populace as a whole; where the ubiquitous presence of the imperial establishment was driven home in the constant succession of honorary inscriptions and stone faces gazing out from the shadow of the colonnades.

Beginning in the fourth century, these porticoes also became the venue in which the will of the state was made manifest in a more immediate and explicit way, in the form of the laws and edicts promulgated by the emperors and their representatives, as Denis Feissel has shown. Until the third century, the inscribed texts of such decrees were regularly displayed at the locations where the popular assembly and city council met: the theater, the odeon, the bouleuterion and the upper agora.113 After the third century, there is not a single example of an official decree posted at any of these places, a clear indication that the traditional organs of civic government were no longer responsible for their publication.114 Of the twenty-five inscribed edicts datable between the mid-fourth century (the earliest belongs to the reign of Constantius II) and the end of the sixth whose original location is well established, fourteen adorned the columns, balustrades and walls of the colonnades lining the Embolos and the Marble Street.115 Feissel’s meticulous study even suffices to trace the migration of newly inscribed acts over time: by the sixth century, when the available surfaces of the Embolos were evidently jumbled with official documents, the inscribers moved on to the adjacent stretch of the Marble Street, covering its porticoes too with a dense patchwork of documents.116 In the process, the colonnades were transformed into an indelible testament to the pull of the imperial will on the lives of the Ephesians, an archive of centuries’ worth of official pronouncements imposed on the consciousness of the masses who traversed the high street of the city on a daily basis.117

The commemorative monuments and legal texts clustered along the Marble Street and Embolos, taken in their entirety, testify eloquently to the centrality of this axis in the minds of the authorities responsible for commissioning them. The profusion of shops in the colonnades indicates that, as at so many other late antique cities, the main street was bustling with commercial activity.118 The numerous game boards inscribed in the pavements of the colonnades at Ephesus and numerous other cities reveal them as places of leisure and social gathering as well.119 The colonnades of the main street at Ephesus, in short, had become the most frequented space in the city, a development that also helps to explain why they were the preferred location for conspicuous forms of epigraphic and artistic display.

But why? Why, when emperors and their representatives became the prime movers behind the shaping of urban infrastructure at Ephesus in the fourth century, did they so assiduously maintain and embellish the architectural décor of a single colonnaded thoroughfare, which progressively subsumed so many of the commercial, commemorative and administrative functions previously more widely diffused throughout the markets, agorai, assembly halls and entertainment venues of the high imperial city?

As at the imperial capitals – Trier, Rome, Milan, Thessaloniki, Constantinople – discussed earlier, so too at Ephesus, I think the answer lies to a considerable extent in the exigencies of public ceremony. The colonnaded processional way was the conduit through which the authoritarian juggernaut of the late Roman state could most visibly and efficiently permeate the heart of the urban center. Not merely grand architectural statements punctuated by honorary monuments to the ruling establishment (which they certainly were), these streets became the main stage for the living tableaux placed before the urban populace, dutifully assembled and arrayed along the porticoes on, for example, the several occasions each year when an incoming governor either made his first adventus into the city, or returned from regular visits to the rest of the province.120 It is for these ephemeral activities, so memorable for participants and so hard for modern scholars to trace in the material record, that the rich corpus of epigraphic evidence from Ephesus is so unusually revealing.

Dozens of extant inscriptions datable from the fifth century into the seventh contain verbatim transcripts of acclamations shouted out by the crowds lining the processional route on special occasions. Like the inscribed edicts discussed earlier, they cluster almost exclusively along the Marble Street and the adjacent section of the lower Embolos. ‘Many years for Christian emperors and Greens!’ ‘Many years for pious emperors!’ ‘Many years for Heraclius and Heraclius, our god-protected lords, and for the Greens!’ ‘Heraclius and Heraclius, our god-protected lords, the new Constantines!’ ‘[Lord] help Phokas, crowned by God, and the Blues!’121 As Charlotte Roueché has said, many of these inscriptions must reproduce the wording of real chants, and they should often be understood to mark the very spot where the recorded words were uttered on one or more occasions, in addition to the identity of the speakers:122 a group of supporters of the Green faction very likely filled the colonnades of the Marble Street where their acclamations are incised, for example, just as the Blues who supported Phokas must have done along the lower Embolos where their chant appears.

A particularly eloquent evocation of a particular time and place in the ceremonial life of the city comes from an inscribed block reused in the paving of a platform leading to the northwest entrance to the theater, recently published by Roueché, which preserves the roar of the crowd as it hailed the adventus of the new proconsular governor of Asia, Phlegethius, into the city around the year 500: ‘Enter, Lord Phlegethius, into your city!’123 The position of the reused block near the intersection of the Arkadiane and the Marble Street suggests that it originated along one of the two streets, and thus on the route the entering governor would have taken on his way into the city from the harbor at the foot of the Arkadiane, where those who uttered the acclamation stood.

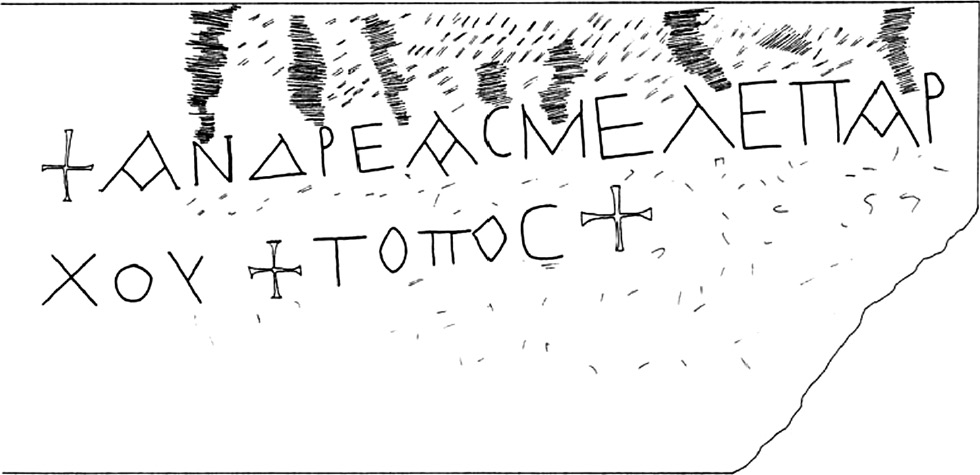

Another inscription preserved in situ within the colonnades of the lower embolos, just past the nymphaeum at the library of Celsus, graphically illustrates the rootedness of specific individuals in the ceremonial topography of the processional way: ‘(this is) the place (topos) of the meleparchos Andreas’ (Figure 3.7).124 Similar topos-inscriptions are attested in late antique urban contexts elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean, where they are generally interpreted as place markers for shopkeepers and other purveyors of services, some of whom are clearly identified as such in the texts.125 In this case, however, the mention of Andreas with his official government title (meleparchos) suggests another interpretation: this is the spot where Andreas, in his capacity as a representative of the civic administration, took his place on ceremonial occasions, when the ranks of spectators arrayed themselves along the parade route according to their rank and station. Whatever the precise duties of the ‘meleparch’ (a hapax, as far as I know), it is evidently the title of a representative of the urban administration, whose official quarters are unlikely to have been sandwiched in among the shops adjacent to the place along the Marble Street where his inscription occurs. We might speculate further: the urban prefects of Constantinople were later known as eparchs; their responsibilities included oversight of all the logistical arrangements necessary for triumphal processions;126 and the tenth-century De caerimoniis aulae byzantinae places the eparch and his staff (the taxis eparchou) along the route of Justinian’s adventus of 559.127 It is thus tempting to imagine that in sixth-century Ephesus, the meleparch was involved in the organization of urban processions, whence it would be particularly appropriate that his ‘place marker’ lies along the heart of the processional route.

Figure 3.7 Topos-inscription of the meleparch Andreas.

The wording of the inscription is suggestively echoed in a sermon delivered by Bishop Proclus of Constantinople (434–46), whose passing reference to the protocols surrounding imperial adventus constitutes the most explicit extant testimony to the existence of what we might call stational chants:

Among the citizens of this world, when they prepare for the arrival of the temporal sovereign, they prepare the way, they crown the city gates, they decorate the city, they thoroughly prepare the royal halls, they arrange choruses of praise, each in its proper location. In these ways the entry of a temporal sovereign into any city is made manifest.128

For Proclus, particular locations along the processional route were associated with specific chants, each of which, like the meleparchos Andreas himself at Ephesus, had its proper place (kata topous). The further implication is that these chants were voiced by discrete subgroups among the urban populace, each of which had its assigned place along the Mese on those occasions when official processions passed along its colonnades.

So much is in fact clear from the literary sources, which show that at Constantinople and elsewhere, the citizenry assembled along the processional route, subdivided by rank and profession, according to a prescribed sequence. According to Libanius, when a new governor made his adventus to Antioch, his route as far as the city gate was lined by senators and ex-governors, current members of the governor’s staff (officiales), local city councilors, and then lawyers and teachers, in that order. Upon traversing the gate, he received the acclamations of the masses, doubtless including the proprietors of the shops lining the street, who thronged the colonnades along his route to the palace on the Orontes.129 When Justinian made his triumphal entrance into Constantinople after the retreat of the marauding Kotrigurs in 559, the Mese from the Capitol all the way to the palace was lined with various corps of government officials, followed by ‘the silversmiths and all the artisans, and every guild.’130 In the tenth century, shopkeepers and craftsmen still clustered according to profession along the colonnades of the Mese, which they presumably helped to decorate on ceremonial occasions.131

The example of Constantinople thus suggests also a substantial degree of interpenetration between ceremonial and commercial topography: the ranks of shops, revetted in marble and decorated by their proprietors on festive occasions, must also – at least in some cases – have been the very place where their occupants stood and voiced their acclamations to passing dignitaries. The section of the Mese called the ‘portico of the silversmiths,’132 then, would not merely have been where the silversmiths plied their trade, but also the place where they participated, as a corporate entity, in events such as the arrival of Justinian in 559, where they feature so prominently in the description preserved in the De caerimoniis.

Serious consideration might then be given to the idea that some of the many topos-inscriptions identifying individuals by name, with or without further information about their rank and profession, may relate to their placement on ceremonial occasions. The phylarch Eugraphius and the ‘most eloquent John,’ for example, whose topos-inscriptions appear on the north portico of the South Agora at Aphrodisias,133 seem more likely to have laid claim to this space in their capacity as distinguished representatives of their city than as permanent occupants of the colonnade. Similar concerns may also better explain the function of the many inscriptions located in close proximity to circles inscribed on pavements at both Ephesus and Aphrodisias, which Roueché has already been inclined to link to the positioning of spectators in attendance at public ceremonies.134 The circles, after all, have no appreciable connection to any sort of commercial activity, but would serve admirably to delineate the space to be occupied by a single, standing individual.135 A remarkable graffito found near the tetrapylon at the crossing of two main roads at Aphrodisias indeed appears to show a figure with one foot in such a circle, arms raised in what might be a gesture of acclamation.136

In any case, while the function(s) of such topos-inscriptions remains open to question, the large corpus of inscribed acclamations alone suffices to demonstrate the transformation of the Arkadiane-Marble Street-Embolos route at Ephesus into a living archive, a repository of institutional memory that ensured that the echo of the ephemeral chants voiced from its colonnades never died away. The memory of the choruses that accompanied the arrivals and other public appearances of the mighty was encoded in the fabric of the street itself, which proclaimed itself, in the voices of the people who assembled there to salute their rulers, a triumphal monument to the imperial establishment. Numerous inscribed acclamations documented at other sites, such as those present on the tetrapylon and adjacent colonnades at Aphrodisias, for example, and others by the propylon at Magnesia-on-Meander, and still others at Phrygian Hierapolis indicate that the main streets of regional centers across the eastern Mediterranean (and almost certainly beyond) experienced a similar transformation in late antiquity, for all that most of the evidence is either irretrievably lost, or awaiting identification by researchers more sensitive to its presence.137 Traces of much more ephemeral painted texts of acclamations, moreover, indicate that the extant inscriptions represent merely the tip of an immensely larger iceberg: by the sixth century, the porticoes along principal urban thoroughfares must have teemed with writing to an extent that is today almost unimaginable.138

The processional avenues that bisected the heart of the leading political and administrative centers of the late empire became, in short, the single most potent architectural manifestation of an ideal consensus between rulers and ruled. They were the stage that framed and reified the social order of the urban collective, its constituent parts hierarchically arranged – and perhaps even prescriptively oriented by inscribed place markers – festively attired, chanting pledges of allegiance to the emperor, the governor, Christian orthodoxy, Christ, Mary, their bishop, their circus-faction and/or the fortune of their city.139 When the residents of a late antique metropolis lined the colonnades along the main processional way to witness the passage of their leaders, they intermingled with the statues of generations of emperors and imperial officials, whose edicts and proclamations peppered the columns, interspersed among the acclamations voiced by the citizenry in honor of these officials on innumerable past occasions, the cumulative legacy of which was evoked by, and integrally connected with, the procession unfolding before their eyes. On all the other days of the year, the profusion of written texts and honorary monuments served as a constant reminder for all comers of those special days when the leaders of the late Roman state put the spectacle of their might and the grandeur of the institutions of government they represented most visibly on display to their assembled subjects, by day and even – perhaps to a still greater extent – by night. The brilliant lighting of the main streets at (inter alia) Antioch, Ephesus and Constantinople must only have increased their relative prominence in the cityscape, and enhanced their propensity to attract and direct the flow of passersby.140

The closely linked imperatives of commemoration, display and ceremonial praxis, in short, deserve pride of place in any attempt to explain why colonnaded streets were so privileged relative to other types of public building in late antique cities, and why, beginning in the Tetrarchic period, imperial and provincial capitals witnessed so much more building activity than the cities that remained more peripheral to the administrative apparatus of the state. Grand processional avenues proliferated in large part for their unique capacity to transform urban landscapes into scenic backdrops, majestic tableaux expressly intended to enhance the public appearances of emperors and their provincial representatives who commissioned and – directly or indirectly – funded them, and to distill the topographical profile of the places they inhabited into a narrowly circumscribed monumental itinerary.

With the growth of the Christian church, the wealthiest and most influential bishops, who themselves tended to be based in the secular capitals in which the metropolitan structure of the church was rooted,141 came almost inevitably to treat these porticated armatures as the preferred venue for the expanding battery of liturgical ceremony over which they presided, and often to annex the churches and episcopal residences they commissioned to the same streets.142 In the fifth and sixth centuries, when bishops took an increasingly active interest in the infrastructure and architectural patrimony of their cities, colonnaded streets indeed featured prominently in the list of construction projects they sponsored. Theodoret, for example, when listing the most significant architectural commissions he undertook as bishop of Cyrrhus in the second quarter of the fifth century, twice cited colonnaded streets in the first place, followed by mention of two bridges, baths and an aqueduct, all underwritten with money from church coffers.143 While the colonnades will undoubtedly have pleased the shopkeepers and passersby who frequented them, and proclaimed the bishop’s stature as a leading patron of his city, one wonders whether Theodoret did not also hope to endow the rather mediocre capital of his remote provincial see with a more distinguished architectural profile, one better suited to magnify the public appearances of a leading figure in the ecclesiastical politics and theological controversies of the age.144 Similar motives may also help to explain why other fifth- and sixth-century bishops chose to embellish their cities with street colonnades; their evident predilection for such structures surely suggests that church dignitaries, like their counterparts in the imperial administration, considered them key features of the urban landscapes they inhabited.145