On 5 May 1954, Mexico City tabloids ABC and Últimas Noticias and mainstream daily Excélsior broke the sensational story of Marta Olmos Romero, recipient of Mexico's first widely known, male-to-female sex reassignment and one of the earliest occurring outside Europe.Footnote 1 Over 18 months (1952–4), Marta's physicians, led by Rafael Sandoval Camacho, successfully deployed surgical, hormonal and psychiatric therapies to engender her transition and, in their view, ‘cure’ male homosexuality; they later self-published their work as Una contribución experimental al estudio de la homosexualidad (1957).Footnote 2 News spread rapidly: ‘The whole country's press has been occupied with this unbelievable case’, exclaimed Diario de Xalapa from Marta's home state, Veracruz.Footnote 3 Some commentators expressed patriotic admiration at the unexpected achievement. Mexican press service Asociación de Editores de los Estados (Association of Editors of the States, AEE) carried coverage nationally as far as Torreón, Monterrey and Guadalajara; initial wires remarked the doctors’ success ‘should be considered a medical triumph in our country, especially considering that only in England and Germany, which have true experts, have interventions of this genre been carried out successfully’.Footnote 4 Wires from US and Australian news services likewise lauded Sandoval's team for achieving only the ‘third “completely successful”’ sex reassignment in history.Footnote 5 Team members argued Marta's transition was ‘a complete success in every detail’, a remarkable feat given the paucity of published guides.Footnote 6 Embodying the triumph and an overnight media sensation, Marta felt ‘spiritually serene’ and expressed delight: ‘Now I have found myself, and I am happy.’Footnote 7

Nevertheless, critics questioned Marta's authenticity, her transition's completeness, the doctors’ ethics and whether sex/gender and sexuality could or should be surgically changed. Alfonso Serrano in Excélsior called Marta a ‘strange specimen’ with ‘odd’ body proportions. Her blonde hair, curly eyelashes, smooth complexion and feminine smile made her a ‘disconcerting case’.Footnote 8 Gynaecologist and International Fertility Association secretary-general Carlos D. Guerrero concurred: doctors could effect ‘a simple, external plastic correction’, but achieving the ‘adopted sex's’ complete biological functions was impossible.Footnote 9 Cartoonist Don Yo smeared Sandoval's team as fame-seeking charlatans.Footnote 10 Prominent Catholic clergy claimed the soul's sex was immutable and sex reassignment cosmetic. Future cardinal Ernesto Corripio Ahumada (then Tamaulipas's auxiliary bishop) argued surgery only ‘fixed’ natural defects; another prelate asserted only a ‘sincere Christian life’ averted ‘bad passions’ including homosexuality.Footnote 11

Marta's case thus evoked important questions about authentic sex, gender and sexuality and where their true seats resided in the body. Were they natal or medically mutable? Had Sandoval's team cured homosexuality, a ‘problem’ gaining increasing public attention after 1917?Footnote 12 If sex, gender and sexuality were changeable, what consequences did sex reassignment pose for nationalism and cultural norms resting upon binary understandings of each? Importantly, Marta's case appeared after sustained international coverage of former US soldier Christine Jorgensen's 1951–2 transition; for many, Jorgensen became a global icon symbolising the scientific possibilities for ‘trans-ing’ sex/gender, but her ‘authenticity’ remained contested.Footnote 13 Against this backdrop, Mexicans debated: Was Marta's transition a major scientific triumph demonstrating development to a global audience? Her case occurred during the three-decade economic Miracle (1940s–1970s) when Mexico sought middle-weight geopolitical status, and the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, PRI)'s ‘dictablanda’ promoted public displays of modernisation.Footnote 14 Supporters viewed Marta's transition as affirming authentic sex/gender, correcting bodily flaws obfuscating her deeper self, and solving the ‘problem’ of male homosexuality. Critics regarded Marta as a deviant renouncing manhood through a fraudulent cure: sex reassignment exemplified misplaced priorities, science run amok and the abrogation of Mexico's moral heritage.

Previous scholarship has examined Marta's case through transphobic violence, US racism, and the ‘eclecticism’ of Mexican sexology.Footnote 15 This article uses Marta's case instead to illuminate tensions in Mexican national identity during a period often characterised as politically stable, if economically unequal. Indeed, Mexicans debated scientific achievement, peso devaluation, food shortages, legal personhood, religion, medicine, tourism and even the PRI's political legitimacy through Marta's case. Her case also challenged state imperatives seeking to ‘modernize patriarchy’ by reforming ‘gender roles in the interests of national integration and development while upholding sexual difference and inequality’.Footnote 16 The state's aim was to produce ‘new’ men and women with specific, useful social roles. Marta's case threatened such a binary with liminal sex/gender and sexuality. As such, her case illuminates the limits of mid-century stability and how the state reconciled development with policing binary sex/gender and sexuality while ‘updating’ its patriarchal sex/gender system. Finally, this article revises interpretations stressing medical coercion. Marta and her doctors believed transitioning enabled her to embody Mexican femininity. Critics disagreed, and through what I call the ‘Christine Effect’, Marta was sensationalised through Jorgensen's case not as exemplifying triumph, but moral perversion, a discursive trope mapped onto earlier claims equating queerness with ‘foreignness’. Ultimately, the state chose to reinforce – and enforce – binary sex/gender through social means versus embracing alternatives enabled by Sandoval's therapies. Sex/gender reassignment, in this view, was anti-Mexican.

Representations in print media, which dominated Mexico's mid-century mediascape, are essential here. More Mexicans read tabloids like La Prensa than national broadsheets like Excélsior; fewer got news from television. Papers also provided content for radio programming.Footnote 17 Both tabloids and satirical cartoonists benefitted from sensationalism and used Marta's case to criticise the dictablanda, testing the limits of the PRI's anti-press censorship.Footnote 18 As such, tabloids and comics, along with mainstream publications, international wires, case files, photos and Sandoval's book-length study, comprise my archive.

For terminology, I use ‘sex reassignment’ rather than ‘gender confirmation/affirmation’ because it conforms to period terminology and meaning. ‘Transition(ing)’ refers to physical, psychological, hormonal and behavioural changes, medical or otherwise, undertaken to transform sex/gender. When discussing Marta prior to transitioning, I use ‘Olmos’, unless sources purposefully used her assigned birth name ‘Jorge’; otherwise, I use her chosen ‘Marta’. Some critics used ‘Jorge’ to downplay her transition; who used which name revealed whether an audience saw her as a cross-dressing, mutilated homosexual, a ‘true’ woman and/or someone worthy of self-determination. I use ‘queer’ broadly to cover Marta's uncertain sexuality and ‘queer embodiment’: how bodies, gender and sexuality were understood intersectionally as non-normative.Footnote 19 Mexicans identified queer persons through terms including ‘afeminado’ (male effeminate, presumed homosexual), ‘invertido’ (sexual invert) and ‘tercer sexo’ (third sex) that denoted sex/gender and sexual deviations from socio-cultural norms. ‘Afeminado’ had the widest use; its long association with foreignness and inauthentic gender performance coloured how many understood Marta's case. None were fully synonymous with ‘transsexual’ and ‘transsexuality’, terms infrequently used in mid-century Mexico, or ‘transgender’, which was non-extant, nor were they exclusive to those seeking transitions.

As such, I use ‘trans’ as a catch-all evoking these categories without being constrained by them or assuming significations from US contexts that subsume local differences.Footnote 20 ‘Trans’ refers to ‘a process or practice’ rather than a ‘fixed identity’: Marta moved ‘away from the gender [she was] assigned at birth’ and ‘trans-ed’ culturally constructed boundaries meant to ‘define and contain that gender’.Footnote 21 Focusing on process pivots from Marta's internal identity towards how she represented herself publicly. She was a ‘gender migrant’ who ‘changed gender on a long-term basis in [her] everyday life’ and deployed strategies ‘to build intimate relationships, control [her] own narratives, and legitimise [her] public gender identities’.Footnote 22

Before Marta

Most well-known trans Mexicans before Marta were trans men. Revolutionary colonel Amelio Robles, who did not surgically transition but embodied patriarchal masculinity convincingly enough to be regarded as a man, was the most famous.Footnote 23 Others included Carmelo Abundio, who transitioned in 1936 under physician Rubén Leñero's care during a 2.5-hour operation.Footnote 24 Leñero subsequently oversaw Juan Bonilla's 1938 transition; Bonilla developed a deeper voice, beard and ‘sturdy physique’ and became betrothed to a woman. Photos showed a smiling Bonilla who ‘smokes, drinks, and goes out with friends’. However, his results proved impermanent, and the couple attempted suicide.Footnote 25 In 1951, Veracruz paper El Dictamen reported that gynaecologist Joaquín Corres Calderón oversaw another ‘young man's birth at age 22!’ through a surgical ‘sex change’ in his military hospital.Footnote 26

The press embraced these trans men and their masculinisation – even celebrating Robles as heroic – though acceptance hinged upon effective gender performances. Their cases also bolstered Mexico's reputation abroad as a site for transitions. Female impersonator ‘Pussy Katt’ went there in 1945; Howard Hughes allegedly paid for her castration, after which they shared a torrid affair.Footnote 27 In 1953, California urologist Henry Weyrauch wrote to Manuel Pesqueira in Mexico's Health Secretariat. Previously, after Weyrauch denied him surgery, a patient had sought treatment in Mexico ‘so that he might become a woman’.Footnote 28 Weyrauch's new patient, Clair Elgin, sought similar treatment. Pesqueira responded, ‘[S]o far as I know, no such operation has been performed in any of our hospitals in Mexico.’Footnote 29 Elgin subsequently self-castrated.Footnote 30

These early cases contextualise Marta's own. Magazine Sucesos para Todos, when discussing Bonilla, claimed that ‘if these operations can be practised on whichever woman or vice versa … such work the surgeons would have!’ – foreshadowing rhetoric discussing Marta, Jorgensen and others seeking transitions.Footnote 31 Foreign wires had reported Bonilla's case, demonstrating Mexican achievements garnered international attention.Footnote 32 And state interest in sex reassignment was revealed: Mexico City's Health Department assisted Abundio's transition, and both Leñero's Hospital Juárez, which he directed, and Corres’ hospital were state-funded. Nevertheless, transitions were not fully within state purview – or, perhaps, something officials always admitted. When Weyrauch wrote to Pesqueira, Marta was three months from surgery.

Marta Transitions

When Marta began transitioning in November 1952, others knew her as Jorge, an athletic 21-year-old men's fashion clerk. A middle child with five siblings, his case history revealed early feminine orientations including preferences for girls’ company, playing with dolls, and maternal role-play – signs, for his doctors, of pathological deviance. As a teen, he ‘imitated his sisters’ mannerisms and habits, occupied himself in domestic labours’, enjoyed creating menus and ‘saw to washing, ironing and sewing his brothers’ clothing’. At 13, his first sexual encounter – with a ‘masculine, tall, well-built, good-looking’ man with whom he felt protected – provoked an enjoyable ‘feeling of voluptuosity’. Openly homosexual, effeminate in bearing, Olmos sought similar encounters semi-weekly. In Sandoval's telling, Olmos was a classic homosexual, whom doctors had failed to masculinise or heteronormativise through hormonal and psychotherapeutic treatments.Footnote 33 But Marta told a different story. Some relatives disapproved of Olmos’ sexuality and femininity; his father denounced him as disgraceful, prompting Olmos to move from Veracruz to live with relatives in Mexico City's south-eastern Unidad Modelo neighbourhood. By 1952, Olmos felt ‘misfortunate and abnormal’ as a man and displayed feminine tendencies. That August, Olmos began feminising hormonal and psychiatric therapies, seeking to correct what he labelled a ‘natural fault’.Footnote 34

Nevertheless, when appearing at Sandoval's clinic in November 1952, Olmos sought treatment for chronic amoebic colitis (a painful intestinal ailment), not a transition.Footnote 35 Sandoval was not yet known as a medical pioneer, nor an obvious choice for providing sex reassignment. After graduating in 1942 from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM), Mexico's most prestigious university, Sandoval specialised in public sanitation and school hygiene, taught high-school chemistry and physics, and co-founded the Sociedad Mexicana de Física (Mexican Society of Physics) in 1950. Yet, he also practised surgery at the Sanatorio Flemming and had developed interests in treating homosexuality surgically.Footnote 36 Their meeting was thus kismet: when Olmos’ ‘aspect, movements, psyche, and feminine expressions drew attention’,Footnote 37 Sandoval saw an opportunity to test his theories and experimental treatments. In turn, when apprised surgical interventions were possible, Marta sought to definitively transition. Each pursued different, if overlapping, goals: whereas Marta wanted a self-affirming means to reveal authentic womanhood, Sandoval sought a ‘humane cure’ for homosexuality.

Sandoval's team viewed Marta through binary sex/gender and homosexuality, rather than trans(gender) identity. Like Spanish sexologist Gregorio Marañón and Mexican medical jurist Leopoldo Baeza y Acévez, they aligned with shifts in ‘Latin sexology’ away from penalising homosexuals (seen as afflicted by intersexual pathologies) towards treatment, whether homosexuality was ‘self-inflicted’ through vice, ‘socially acquired’, situational or congenital.Footnote 38 Ideas from prominent sexologists including Magnus Hirschfeld, Cesare Lombroso, Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Sigmund Freud, Havelock Ellis and Alfred Kinsey, as well as from activists Karl Ulrichs and Donald Webster Cory, influenced Sandoval's conclusion that homosexuality was pathological but not intractable.Footnote 39 Nevertheless, trying to suppress it through psychotherapy and hormones, or by reorienting sexual desire toward heteronormative objects, left an irresolvable, ‘implicit antagonism between the psychic and the somatic’.Footnote 40 Moreover, too few competent analysts existed to successfully implement widespread treatment. Sandoval also rejected therapies helping queer men adjust to societal hostility and live openly; for him, validating an individual's homosexuality left their worrisome structural and functional issues unresolved. Instead the psyche, body and comportment needed therapeutic alignment to enable normative social reintegration. This, Sandoval wrote, was his noble calling: doctors – with their daily encounters with patients – had particular insight into the human condition and were thus uniquely positioned to delineate essential, ‘natural’ norms governing human existence, including binary sex/gender and heterosexuality.

With Olmos’ consent, Sandoval and interns Antonio Mercado Montes, Carlos Dupont Bribiesca and Marco Antonio Dupont completed a clinical case study, diagnosing him with an ‘intersexual syndrome’ manifesting in homosexuality and feminine mannerisms, habits and libido.Footnote 41 They researched Olmos’ biography, noting childhood illnesses, a cousin suffering ‘oligophrenia’ (‘interrupted mental development’ associated with hysteria and homosexuality), his preference for flashy masculine attire, and desires to cross-dress. They conducted anthropometric examinations; Binet–Simon and Raven intelligence tests; Rorschach, Szondi and Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) psychodiagnostics; and blood tests. These allegedly revealed pathologies: the Rorschach showed ‘sexual complexes’ causing insecurity and anti-societal aggression, while the Szondi evinced hysteria and ‘feminine sexual tendencies accompanied by the need to constitute himself as a love receptacle, and an intense desire to receive tenderness’. More troubling, his ‘strong depressive and hysterical states’ prompted thoughts of suicide. While Olmos’ genital measurements proved normal, his pubic hair had a ‘feminine’ triangle pattern, and he had a ‘funnel-shaped anus’. Both were bodily ‘stigmata’ through which Mexican sexologists diagnosed ‘degeneration’ and ‘passive homosexuality’.Footnote 42

Sandoval's team concluded Olmos had a ‘conscious and unconscious opposition to the contradiction between his physical appearance and psychological processes of a feminine character’.Footnote 43 He thus fit arguments positing homosexuals as maladjusted, effeminate, potentially violent, psychosexual hermaphrodites whose bodies, even when morphologically ‘normal’, did not correspond with their psyches or desires. Olmos’ outward appearance – muscular limbs, flared back, slim waist, masculine face – appealed because if he could be transformed, then the physicians’ methods would be demonstrably efficacious.Footnote 44 Since previous treatments failed to make Olmos a masculine heterosexual, Sandoval's team argued that surgical sex reassignment – supported by psychiatric and hormonal therapies – would rectify his dysphoria and reorder his bodily stigmata, thereby ‘curing’ his homosexuality. Reordered anatomy would enable normative sexual acts (i.e., vaginal rather than anal sex) and romantic interactions; whereas Jorge desired men pathologically, Marta desired men (hetero)normatively. Moreover, following the Mexican Revolution, ideas that ‘anti-social’ deviants should be ‘rehabilitated’ – or prevented from ‘contaminating’ others – permeated politics, medical jurisprudence, eugenics and education.Footnote 45 By transitioning, Marta could be (re)incorporated into the civic fold as a ‘socially rehabilitated’ woman, useful in advancing the post-revolutionary state's vision for a better national future.

On 26 May 1953, Marta's first surgery removed her penis and took biopsies of her testicles, which allegedly showed ‘atrophic degeneration’, a ‘sign’ of perceived deviance or homosexuality. Subsequent surgeries, borne stoically, included orchiectomy and vaginoplasty using a segment of her intestine; the last surgery occurred on 10 March 1954. Out of six surgeries, four occurred in private clinics, including surgeon Adolfo Pérez Montero's clinic, and the remainder at Marta's home. Sandoval's team tapped specialists for additional diagnostics and therapies promoting feminine development, but acknowledged some secondary sexual characteristics – a deep voice, facial hair – could not be fully reversed. After 45 days, post-surgical, ‘eunuchoid’ characteristics, including abnormal fat redistribution, subsided; further treatment developed Marta's breasts and feminine form. Throughout, doctors photographed her body and their procedures, proudly extolled their methods, presented Marta to the press and screened surgical films for colleagues.Footnote 46

Sandoval's team had reason to believe their treatment set precedents: it occurred when Mexican science was earning international acclaim. In Mexico City in 1951, Laboratorios Hormona and associated company Syntex, headed by Hungarian émigré George Rosenkranz, pioneered an industrially viable method for synthesising cortisone from Mexican yams (Discorea sp.). Concurrently, Luis Miramontes, working under Rosenkranz and Bulgarian chemist Carl Djerassi, first synthesised the progestin norethindrone. Used for fertility treatments, norethindrone was later combined with oestrogen in the first oral contraceptive.Footnote 47 Syntex provided the oestrogen and progesterone Marta's transition required, making her a test subject for their products and Sandoval's therapies alike.Footnote 48

Syntex's participation illuminates why Sandoval's team, before Marta's case became sensationalised, enjoyed support from President Adolfo Ruiz Cortines’ (1952–8) inner circle. Sandoval publicly credited lawyers Manuel Rangel y Vázquez and León Méndez Berman – Ruiz Cortines’ long-time assistant and newly appointed Tribunal Fiscal (Tax Court) magistrate – with funding and morally supporting Marta's costly transition.Footnote 49 Such support seems unlikely without state interest in what initially appeared to be Mexico's next scientific triumph. Further technical support and credibility came from noted professionals, including eminent criminologist Alfonso Quiroz Cuarón, who had published studies on homosexuality, social degeneration and crime since the 1930s, integrating sexological, psychiatric and endocrinological methods.Footnote 50 Regarding homosexuality as dangerous, Quiroz nevertheless saw imprisonment as ineffective. Thus, the stage seemed set for wider adoption of Sandoval's solution. Understanding why this solution was not adopted, at least with public support, requires exploring how Marta understood her transition and publicly represented herself; how the press, local and international, covered her in relation to Jorgensen; and how the Mexican state, public and physicians reacted to her case and related sensationalism.

Representations

Siobhan McManus has argued Sandoval's team coerced Olmos into transitioning rather than treating his gastrointestinal ailments; for McManus, their therapies comprised institutionalised homophobic violence directed at Marta and others considered deviant in sexual and gendered terms.Footnote 51 Indeed, despite their evaluations describing Marta as ‘intellectually deficient’ – and thus potentially unable to understand or consent to transitioning – the doctors proceeded anyway.Footnote 52 In context, though, the argument for coercion seems less certain. Sandoval asserted Marta's transition occurred consensually, praising her ‘incomparable bravery’ given the potentially fatal risks.Footnote 53 Marta expressed her intentions publicly: ‘I felt feminine impulses. I liked to cook, sew, and keep house. Although strong, I didn't like to rough-house with other boys. I finally took this step to end my torment.’ Though admitting a lengthy, painful convalescence, she remained steadfast: ‘I believe in becoming a woman, I've really found myself. I'm perfectly satisfied with my new situation.’Footnote 54 Such statements affirmed her intentionality and, perhaps, trans identity: Marta ‘had been liberated’ to pursue feminine interests previously denied her. Though some relatives rejected her transition – working to legally forestall it – her mother, Refugio Romero, relented, and her younger sister, Soledad, supported her.Footnote 55 Men showered her with propositions, and Marta revelled in new-found publicity: in a Faustino Mayo photo, she smiles, reading ABC's coverage with Soledad (see Figure 1).Footnote 56

Figure 1. Marta and Soledad

Source: Archivo General de la Nación, Fondo Hermanos Mayo, CR7721.

TAT interviews conducted before and after Marta's surgeries further illuminate her motivations. These interviews, in which clinicians showed Marta 20 images depicting ambiguous social situations, were intended to elicit her understanding of interpersonal relationships. While a full analysis exceeds this article's scope, her fictional, but still self-referential narratives clearly corresponded with her public statements. Throughout, Marta expressed gender fluidity, identifying with images she read as depicting dutiful sons and spurned women alike. Pre-transition narratives referenced depression, self-loathing and suicidal thoughts; several revealed resentment towards society, unloving fathers – recalling Marta's estrangement – and untrustworthy lovers. ‘I remember the men who ruined me’, she lamented. ‘I hate them and will never again believe in anyone even if my life is ice-cold.’Footnote 57 But other narratives demonstrated resilience and self-actualisation instead. One referenced a hardworking son remitting money home, forcing parental recognition. Another described a diligent violinist showing filial respect yet seeking personal fulfilment. And in several post-transition narratives, Marta's characters expressed optimism about self-improvement through hard work, finding romance and earning higher social status.Footnote 58

Such narratives revealed her longings for respect from her family and society. They also foreshadowed how Marta astutely crafted her public image to reinforce her physical transition's legibility and authenticity, so as to be accepted and respected as a woman. In press interviews and photos, she appeared as a hardworking, elegant, feminine paragon performing womanhood and fulfilling stereotypical domestic roles – cooking, cleaning, flirting, applying makeup, wearing summer dresses, shopping, holding a baby (see Figures 2 and 3). She proclaimed desires to marry, have children and return to work, this time selling women's attire, performatively completing her transition towards ‘normalcy’.Footnote 59 And she validated Sandoval's theory: as a homosexual man, she could not find love; as a (trans) woman, she could.Footnote 60

Figure 2. Domestic Marta

Source: ABC, 8 May 1954.

Figure 3. Shopping

Source: Archivo General de la Nación, Fondo Hermanos Mayo, CR7721.

By transitioning and performing femininity, Marta positioned herself as a respectable, socially useful, suitably gendered agent within modernising patriarchy and the ongoing Revolution, rather than a disaffected, suicidal, ‘anti-social’ deviant. Marta also claimed status as a bona fide Mexican woman by professing faith in an era of resurgent conservativism and Catholicism, choosing her name after praying to Martha of Bethany, patron saint of housewives, while transitioning.Footnote 61 Believing her prayers answered, Marta hoped to be re-baptised, something Catholic prelates dismissed; they called her transition ‘illicit’ for, in their view, unnecessarily mutilating a healthy male.Footnote 62 Nevertheless, one striking Hermanos Mayo photo depicted Marta holding a Virgen de Guadalupe statuette beneath the Virgen's image, doubly linking Marta's femininity with the archetypal Mexican icon of faith, nationalism, womanly virtue and motherhood (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Icons

Source: Archivo General de la Nación, Fondo Hermanos Mayo, CR7721.

Simultaneously, Marta positioned herself as a legible, universal woman epitomised by blonde hair and pale features in clear reference to others who transitioned internationally. While early photos showed Marta with dark hair, later photos showcased her chemically dyed coif in wavy, ‘autumnal symphony style’.Footnote 63 Emily Skidmore has argued Jorgensen's transition into a ‘blonde bombshell’ was significant because she rejected being deviant, a cross-dresser or queer in favour of status as a mainstream, heteronormative, White woman.Footnote 64 Marta, it seems, sought the same: her own blonde ‘bombshell’ look referenced Jorgensen and stars like Marilyn Monroe, whose femininity was incontestable. As such, at least initially, Marta evoked the international cachet of ‘Whiteness’ convincingly: ‘She is White’, La Prensa declared, suggesting she had transitioned race, as well as sex/gender. Journalists thus joined Marta in promoting her as a potential Hollywood, rather than Mexican-style, movie star. Stardom initially seemed possible.Footnote 65

The ‘Christine Effect’

Marta's transition followed international coverage of Jorgensen's and Charlotte McLeod's transitions in Denmark, Roberta Cowell's in Italy and Xie Jianshun's in Taiwan, all of whom the Mexican press also discussed.Footnote 66 From the moment Marta's story broke, commentators situated it within national and international debates, asking whether those transgressing sex/gender norms were emblematic of positive, universal modernity or of anti-nationalist degeneration. Indeed, Marta's visible similarity with foreigners raised implications for her acceptance as a Mexican woman. Her ‘universal’ image challenged indigenist archetypes of race, nation and identity – which had gained importance as part of the post-Revolution ‘crafting’, ‘ethnicization’ and ‘browning’ of nationalist mexicanidad (Mexicanness).Footnote 67 In this, she echoed earlier women, including 1920s-era pelonas (modern girls), whose appearance challenged nationalist imagery.Footnote 68 She transitioned away from ‘official’, Mestizo, national womanhood – signified by dark hair – to White, blonde, international womanhood. But this was not the racial ‘improvement’ sought by eugenicists and nationalists: José Vasconcelos himself, architect of the indigenista ‘cosmic race’ theory, called Marta ‘nauseating’.Footnote 69

‘Foreignness’ had long been used to smear individuals such as pelonas and nineteenth-century dandies, who transgressed sex/gender norms, and distinguish them from ‘normal’, ‘authentic’ Mexicans.Footnote 70 This trope also gained particular prominence following the Famous 41 scandal (1901), in which police raided a party of men, half in drag, who were seen as emblematic of the Porfiriato's ‘foreign’, libertine excesses. The scandal, the most famous queer event in Mexican history, brought wider attention to the ambiente (as the queer social world was known) and publicly linked male effeminacy and homosexuality as synonymous. For decades thereafter, discourses about the Famous 41 framed how many understood queer embodiment.Footnote 71 Coverage of Marta's case updated this trope: it conflated afeminados – already seen as cowards and traitors to their sex – with those seeking transitions. Both were ‘foreign-influenced’, androgynous threats to nationalist patriarchy who would surgically, rather than just performatively, renounce masculinity and nation.

Jorgensen's case played an important role in this reframing – and how transitioning and its implications (scientific, political, cultural, ethical) were understood. Following reports of Jorgensen's transition in 1952, transitions enjoyed often positive coverage in Mexico. In wires, Jorgensen expressed satisfaction as a ‘perfectly natural woman’ – words Marta later echoed.Footnote 72 Articles claimed Jorgensen ‘excited the world’, asked readers ‘Do you want to change your sex?’, played with liminal gender in Spanish linguistic terms, and described sex reassignment as ground-breaking medicine.Footnote 73

Yet, doubts grew about her transition's veracity. Guadalajara's El Informador quoted Jorgensen's doctor, Christian Hamburger, in April 1953 admitting that ‘sex cannot be changed’.Footnote 74 Critics also sought to reinforce gendered social orders and binary sex/gender's immutable innateness. In October 1953, the same month Mexican women gained suffrage, officials banned Jorgensen, who performed worldwide, from giving live shows, fearing she would ‘foment morbid curiosity’ and incite ‘improper’ behaviours.Footnote 75 Reports refracted local events through the Christine Effect. In 1954, journalist Dalton Romay described ‘an inverse case’ of Jorgensen: a person named ‘Núñez’, whose sex ‘spontaneously’ changed from female to male. Núñez then seduced a 16-year-old, committing ‘an outrage upon her that only a ruinous man could’. Interrogated, Núñez declared ‘I am a man! … I will marry her and woe to anyone who tries to stop me!’ Nevertheless, accompanying photos depicted Jorgensen, not Núñez, solidifying the connection for readers of his ‘otherness’.Footnote 76

Sensational coverage of Jorgensen remained bankable, particularly in tabloids. For years after her transition, crime tabloid Magazine de Policía labelled queer Mexicans ‘Cristinas’. Romay, for instance, disingenuously argued afeminados cross-dressing during Veracruz's carnival emulated Jorgensen, thus bolstering old stereotypes that afeminados, a repulsive ‘third sex’, wanted to be women.Footnote 77 Later stories referencing Jorgensen and Cowell warned the ‘Christines are multiplying!’ ‘All the universe's homosexuals […] yearn for a similar operation’, one claimed; afeminados would willingly suffer a ‘series of tortures’ instead of being ‘contemptible beings’. The tabloid snarked doctors would find success in Mexico, ‘where there are plenty of homosexuals who feel that they are Cristinas, without the operation’.Footnote 78 Some certainly wanted transitions: following Jorgensen, some 300 individuals, including Mexicans, sought them in Denmark, prompting the country to prohibit transitions for non-citizens just as Marta's story broke.Footnote 79 For critics, what was worse was that Cowell's case revealed ‘real’ men might also seek transitions: Cowell's transition was scandalous because he had been a ‘macho among machos’, RAF pilot, worker and married father, not an effeminate homosexual.Footnote 80

This was the context for ABC's 5 May 1954 cover with the exasperated caption ‘The only one we lacked!’ / ‘That was the last straw!’ (see Figure 5).Footnote 81 Accompanying photos linked Jorgensen, Cowell and Marta as part of the same phenomenon. ABC's 7 May 1954 editorial – which denied sex could be changed – then blamed Jorgensen and Cowell for Marta's desire to transition: their publicity so corrupted Jorge that he, ‘a George – slayer of dragons – decided to convert himself into sweet Marthita, just so, with “th”’.Footnote 82 ABC's editors – referencing England's patron saint and Christian mythological hero – saw Marta as tragic: a manly ‘hero’, influenced by deviant foreigners, transformed into a lisping mockery of womanhood and, like Jorgensen, another fallen ‘George’.Footnote 83 Marta's trans womanhood was thus an ‘import’ at a time of nationalism, indigenismo, modernising patriarchy, and scepticism towards foreign ‘contamination’.Footnote 84 She evoked earlier cases where the ‘national’ was defined against a foreign, queer, grotesque other.Footnote 85 After initial enthusiasm, the conceptual space for considering trans(sexuality) as a Mexican state of being – and transitions as legitimate for achieving it – withered. Marta instead epitomised an afeminado/‘Cristina’ defrauding the public.

Figure 5. ‘¡Lo único que nos faltaba!’

Source: ABC, 5 May 1954.

Receptions

Mexico City-based print media dominated coverage of Marta's case. Excélsior interviewed Marta and published reports, an editorial cartoon and a letter to the editor, but offered restrained coverage compared to the splashy, in-depth, front-page, photo-heavy coverage in its tabloid Últimas Noticias, supplement Magazine de Policía, and competitors ABC and La Prensa. PRI mouthpiece El Nacional and conservative-leaning El Universal offered only minimal coverage. Regional papers, including Diario de Xalapa, published coverage; several AEE wires appeared in member papers including El Siglo de Torreón, El Informador and El Porvenir. What impact Marta had on regional understandings of sex/gender and sexuality remain to be researched. Nevertheless, this range of publications points to nationwide knowledge of her case, which might even be the forgotten origin of ‘operación jarocha’ (‘Veracruz operation’) – today slang for surgical transitions – since she was from Veracruz.Footnote 86

How tabloids covered Marta mirrored how they sensationalised homosexuality, crime and violence. Papers competed for scoops; interviews, photos and narrative arcs played out across days to stoke reader interest.Footnote 87 Papers often offered contradictory ‘hot takes’. For instance, some early reports argued Marta was treated for a medical issue, a perspective Sandoval's team advanced. Widely, nationally circulating La Prensa stated that Marta's surgeries occurred for honourable, medically necessary reasons: she was ill, trapped in the wrong body, and deserved help because she was not a deviant, vice-laden homosexual. This argument rested on twin claims: (i) Marta had an innate pathology and (ii) lacked vice-laden habits prior to transitioning, which would have suggested her culpability in ‘choosing’ or ‘acquiring’ homosexuality, rather than her being ‘naturally’ ill. Additionally, the paper regarded the significant pain she endured as evidence her transition was legitimate, rather than frivolous.Footnote 88 Subsequently, La Prensa explained Jorge's inner struggle: rather than desiring women, he wrestled with whether he was himself a woman.Footnote 89 At first blush, these claims seem sympathetic towards Marta as trans. Yet, La Prensa instead homophobically recast her transition through a Freudian model of homosexuality: Jorge's narcissistic deviancy pushed one admirer, her passions unrequited, to attempt suicide. If only he had indulged the women pursuing him, La Prensa posited, he could have lived an authentic, ‘normal’ life.

Criticism soon eclipsed positive coverage. One common argument said Marta's transition was cosmetic: she remained male and a poor approximation of women because treatments failed to remove all masculine traces.Footnote 90 This notion rehearsed a long-running sexological and popular idea: afeminados wore ‘veneers’ – fashion, makeup, feminine performances – masking physical bodies that, when exposed, revealed them as deviant counterfeits. For instance, medical jurists Luis Hidalgo y Carpio and Gustavo Ruiz y Sandoval claimed in 1877 that afeminados wore clothing flaunting their bodies and ‘natural voluminous buttocks’. Afeminados cared ‘greatly for styling and curling their hair, which, like their clothing's clean exterior, contrasts with their interior clothing's shameful filth’.Footnote 91 In 1932, Óscar Urrutia's Don Chepe y Mr. Puff comic depicted bumbling detectives Chepe and Puff in the Zócalo, Mexico City's central plaza, cruising pretty ‘women’ later revealed to be afeminados.Footnote 92 As such, while sex reassignment suggested bodily truths could be re-fashioned, most critics saw only cosmetic veneers inscribed directly upon the body, which contained deeper, immutable characteristics: the soul, ‘real’ anatomy, and biological sex. Those who transitioned were not ‘real’ women, just afeminados. Consequently, critics placed feminine terms describing Marta in scare quotes, questioning her legitimacy as a woman. La Prensa reported some women rejected Marta as truly representative of their sex/gender.Footnote 93 Popular exotic dancer and cabaretera (cabaret/brothel film) star Brenda Conde denounced Marta's ‘sex transmutation’ and ‘protuberances’ (breasts) as fake: ‘This one is nothing more than an afeminado.’Footnote 94 Conde may have feared competition: Marta hoped to dance in cabarets, which scandalously employed afeminados to their benefit.Footnote 95 A related, if distinct, criticism appeared from male critics. One Universal Gráfico comic satirised trans women as ‘false’: two men discuss a job applicant, whose legs are visible through a doorway. ‘I don't need reference letters!’ the boss exclaims. ‘What I see is sufficient, only I want to prove she is an authentic woman and not one of the sexually transformed.’Footnote 96 The sexist comic thus suggested that straight men could demand physical exams – and sex – to prove women's ‘authenticity’. Another critique questioned whether transitions distilled feminine beauty or amplified afeminados’ grotesquery. One Magazine de Policía cover mocked Marta, asking, ‘the new girl is very attractive, right?’Footnote 97 A Jueves de Excélsior comic depicted a hybrid Marta/Jorge: half woman, half effeminate dandy, another afeminado stereotype.Footnote 98

These critiques revealed how transsexuality and possibilities of ‘changing sex’ caused public unease, further provoking attempts from multiple quarters to police binary sex/gender and sexuality. While some reports portrayed Marta as authentic in her womanhood, most saw a deviant afeminado performing inauthentic womanhood. Moreover, if sex reassignment could not produce feminine beauty, the motives behind surgeries became even more suspect. And while acquiring actual womanhood required intentionality and gender performances – hence Marta's publicised domesticity – these alone did not sufficiently validate womanhood. Nor did Marta's professed interests in marriage, becoming a good wife and having children, something Sandoval's team considered initially possible.

At the same time, as happened with Jorgensen's case, prominent medical professionals debated the veracity and necessity of Marta's transition – and transitions in general. Alfonso Pruneda, UNAM's ex-rector and Secretaría de Salubridad y Asistencia (Secretariat of Health and Care, SSA) advisor, argued there was ‘insufficient scientific data’ supporting transitions; doctors ‘worthy of the name’ should not intervene, as Marta's outcomes were ‘unsatisfactory’.Footnote 99 Others voiced cautious, if limited, support in cases of ‘true hermaphroditism’ or indeterminate sex.Footnote 100 Echoing Sandoval, Joaquín Ramírez and José Figueroa reasoned physicians should intervene against sexual anomalies; Iván Audry advocated establishing whichever sex ‘enabled a socially integrated being’. SSA official Demetrio Mayoral and Domingo Olivares (Hermosillo, Sonora's mayor) argued it ‘more beneficial than prejudicial […] to delineate in the physical body that which already existed in an individual's psyche and hormonal constitution’.Footnote 101 Francisco Quiroga averred ‘degenerates’ should be permitted to cross-dress and surreptitious surgeries offended neither ‘society [n]or Nature’.Footnote 102

Nevertheless, as with Jorgensen's case, many feared publicity undermined any medical value. As ABC's 7 May 1954 editorial put it: ‘to the thousand and one immoralities plaguing our environment, we must add another of unconfessable nature and gravest social damage’.Footnote 103 Mayoral denounced Marta's publicity as a morbid social danger for anyone lacking sufficient scientific knowledge to understand sex reassignment; he and Vasconcelos believed her case should have been known only to experts. Publicising it where children might see was a monstrous ‘crime against the spirit’.Footnote 104 Even worse, Quiroga warned, publicity might proselytise homosexuals who did not actually need surgery.Footnote 105

‘Gynaecologists for Androgynes’

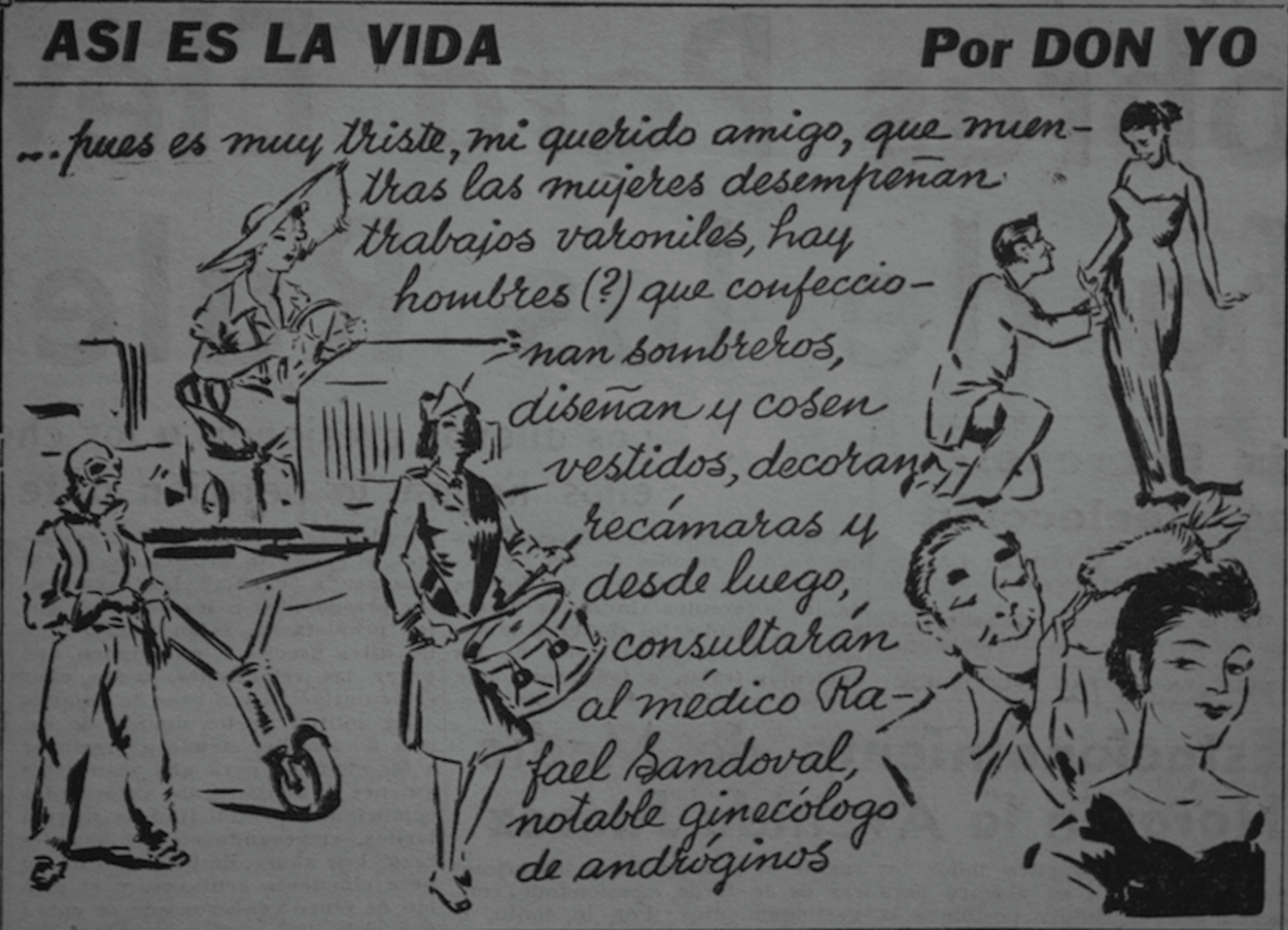

Cartoonist Yo repeatedly amplified such criticism in his ‘Así es la vida’ (‘Such Is Life’) comic in tabloid La Prensa: Marta's transition undermined sex/gender norms and her self-interest alike because her doctors defrauded her through quixotic experiments. On 10 May 1954, Yo acknowledged Marta's significance but lambasted Sandoval's team as ‘gynaecologists for androgynes’: shameless opportunists selling the ‘most sacred professional secrets’ for fame and fortune. ‘If Jorge or Marta poses and exhibits herself – that's up to her!’, he wrote, ‘… but the doctors … poor professional ethics! … Poor Hippocrates and his oath!’Footnote 106 Subsequently, prominent physicians José Castro (director, Escuela Nacional de Medicina) and Rafael Segura (director, Distrito Federal's Federación Médica, a pro-state medical association) denounced charlatans conducting illegal procedures, producing false death certificates, promising dubious cures, exploiting patients financially with long-running treatments, and contravening ‘moral principles’ by conducting ‘surgical interventions whose simple mention horrifies’. For them, Sandoval's team epitomised a culture of ‘bankrupt medical ethics’.Footnote 107

Yo's subsequent cartoon on 12 May 1954, portraying four afeminados preening, rehearsed a trope found in Bonilla's case and the ‘Cristinas are multiplying’ hyperbole: ‘[T]he future of D. Rafael Sandoval and assistants Dupont and Mercado, “specialists in androgynes’ gynaecology”, is secure. They will have Mexico's most select clientele.’Footnote 108 While many afeminados had not sought transitions – some claimed to already distil femininity – Yo echoed those assuming all now desired to emulate Marta because travel was unnecessary, including Excélsior's conservative cartoonist Rafael Freyre, who depicted afeminados discussing Marta over coffee: ‘How excellent! … a trip to Denmark would be very expensive’, one exclaims (see Figure 6).Footnote 109

Figure 6. ‘Changes’

Source: Excélsior, 6 May 1954.

ABC's 7 May 1954 editorial warned of ‘clandestine clinics under Ferdinand the Bull's sign’ appearing where a ‘multitude of gullible fags’ submitted to the ‘scalpel's rigours hoping for an advantageous marriage with a rich heir, or a more satisfactory one with a robust conscript’ and urged vigilance against those offering afeminados ‘honeys Nature denied them’.Footnote 110 Magazine de Policía's 17 May 1954 editorial continued the trope, claiming ‘freak shows’ would exhibit transitioned individuals alongside headless men and beastly women.Footnote 111 Its 20 May 1954 ‘Buscabullas’ (‘Troublemakers’) comic depicted an onlooker shocked by ‘loads’ of equivocados (‘wrong ones’) seeking transitions (see Figure 7).Footnote 112 ‘Martas’ now replicated like ‘Cristinas’.

Figure 7. ‘Troublemakers’

Source: Magazine de Policía, 20 May 1954.

Yo's third comic on 14 May 1954, targeted Sandoval's ‘androgynous’ clients: ‘So it is very sad … while women perform masculine jobs, there are men (?) who make hats, design and sew clothing, decorate rooms and, of course, consult doctor Rafael Sandoval, notable gynaecologist of androgynes.’ (See Figure 8.)Footnote 113 Yo's concerns tapped into criticisms circulating since the fin-de-siècle that targeted homosexuality, male effeminacy, and feminism as threats to Mexican civilisation and patriarchy; they recalled, for instance, a famous 1907 La Guacamaya cover captioned ‘Feminism Imposes Itself’, depicting afeminados at domestic labours.Footnote 114 Such concerns were again acute in the 1950s – sex reassignment became publicised while women's suffrage, achieved in 1953 after decades of struggles, and shifts in sex/gender norms elicited debate. In January 1953, Jueves de Excélsior quoted lawyer Rafael de la Garza stating women's suffrage distracted from more ‘serious’ socio-economic problems.Footnote 115 A week later, Freyre's cover depicted a man juggling children as his wife tasked him with chores before she headed to the legislature; male effeminacy was the undesirable result of women's power.Footnote 116 Rehearsing this rhetoric, Yo argued sex reassignment, by engendering feminisation, worsened this trend.

Figure 8. ‘Such Is Life’

Source: La Prensa, 14 May 1954.

Yo's 17 May 1954 final comic on this theme stated: ‘It is a tragedy, a veritable tragedy. Poor Marta Olmos cannot, no more than has already been done, sweeten her voice and … project a melodious timbre; but Marta, poor thing, shouldn't despair: Recall … Dame María Félix, Negrete's widow, is very hoarse …’Footnote 117 Rather than offering compassion, Yo jibed Marta for counterfeit womanhood. While Félix was a feminine icon – and Jorge Negrete a masculine paragon – she also dated women, including French cabaret owner Frede.Footnote 118 Yo's back-handed compliment suggested Marta might indeed snag a ‘real’ man, but lingering ‘hoarseness’ revealed her heteronormative femininity as an inauthentic, performative veneer, much as hoarseness undermined Félix by evoking butch bisexuality.

Broader Implications

Yo's comics appeared during debates on the practical – and national – implications of Marta's transition. Could she change her legal status to female, marry, or have children? Would new birth and baptism certificates validate her status?Footnote 119 Such questions concerned jurists including Rodolfo García, who warned sex reassignment posed a ‘grave social-juridical problem’. For him, biological sex and personal names were ‘characteristics of distinction’ defining individuals. While notaries could change names for healthy adults, legally changing sex needed to be prohibited except in medically necessary cases. Otherwise, ‘whatever man, delinquent, spy or mentally deranged person could commit a multitude of atrocities just by becoming a “woman” for some months or years’.Footnote 120 García's hyperbole evoked long-standing fears of feminisation and women's power, as well as stereotypes of mental illness, crime, and cross-dressing afeminados ‘duping’ others. It also deployed culturally conservative, Cold War-era rhetoric linking ‘moral deviance and subversion’: like peers across the hemisphere, he imagined lavender and red scares where undetected queer, communist, criminal fifth columns undermined the nation.Footnote 121 Sandoval's ‘cure’ thus fostered conditions worse than it treated.

Other criticism invoked local political and socio-economic issues. Marta's transition occurred halfway through the Mexican Miracle's period of economic growth and middle-class expansion. Yet the Miracle offered uneven benefits.Footnote 122 In 1948 a serious devaluation and food crisis stoked open criticism against cronyism during Miguel Alemán's administration. Middle-class housewives, soldiers, merchants, workers and the satiric press all blamed corruption for causing poverty and financial difficulties. Their scathing rebukes triggered secret police raids and censorship constraining print satire in Mexico City to editorial cartoons.Footnote 123 These events presaged how Marta's case, appearing as new financial problems roiled Ruiz Cortines’ presidency, was received. Cartoonists satirised it in relation to this crisis. One depicted campesino ‘Pioquinito’ cowering near a doctor: ‘Did you come here for a sex change?’ he asks. ‘No … just to change my luck.’Footnote 124 Readers understood the subtext: the peso was devalued from approximately Mex$8.65 to 12.50 per US dollar in April 1954.Footnote 125 Officials claimed devaluation solved problems stemming from the post-Korean War recession and profligate spending under Alemán's administration.Footnote 126 Instead, devaluation undermined confidence in the peso, and consumers and industry lost spending power.Footnote 127

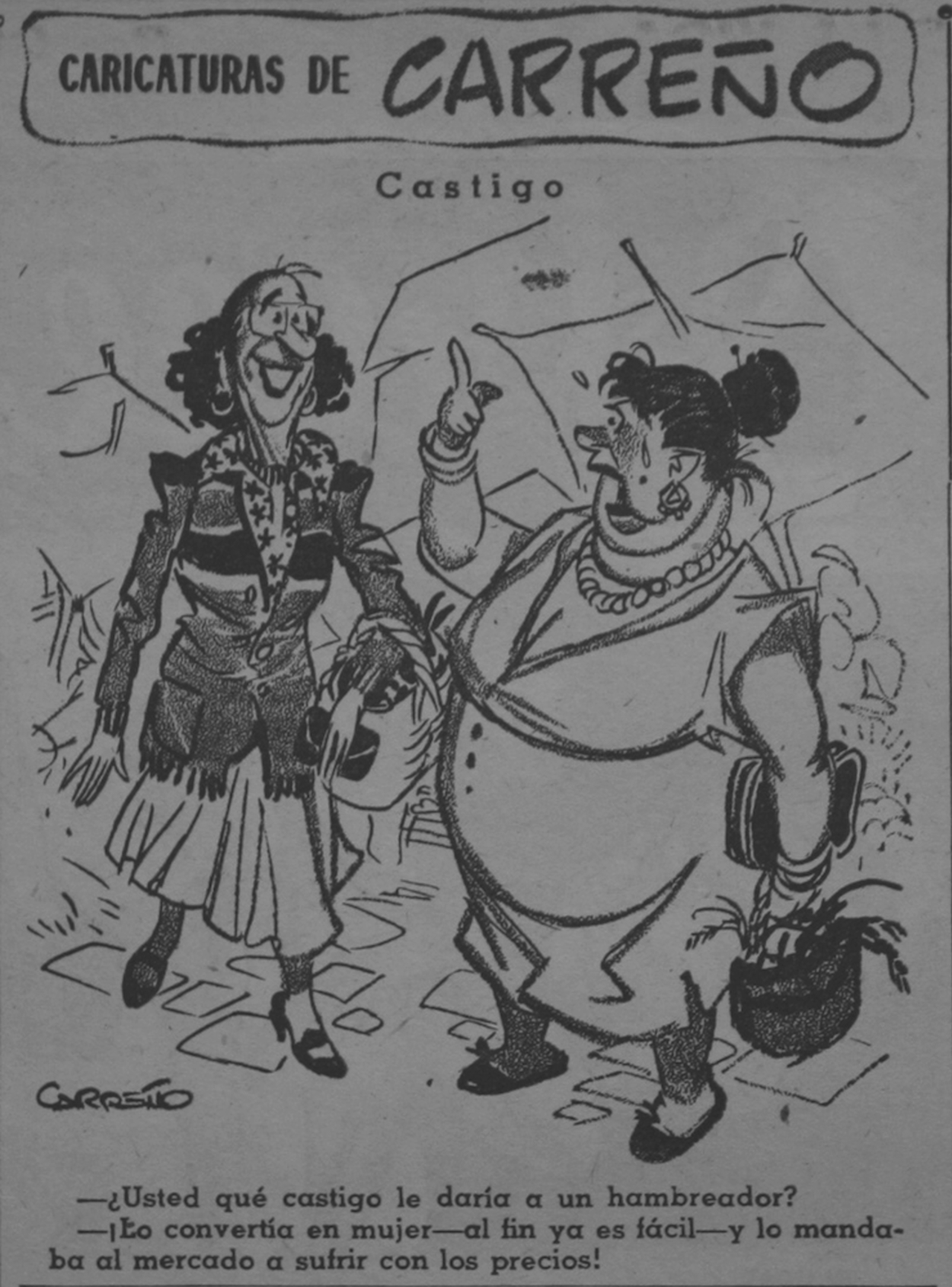

Simultaneously, Mexico City faced increasing food prices and meat shortages. These shocks engendered calls for ‘war’ against exploiters. Fidel Velázquez, leader of the labour syndicate Confederación de Trabajadores Mexicanos (Confederation of Mexican Workers, CTM), a powerful constituent of the PRI, argued the ‘Mexican people will not sacrifice further’ and advocated sending exploiters to the Islas Marías penal colony – a punishment used against habitual criminals, political prisoners and queer Mexicans.Footnote 128 Jorge Carreño's 8 May 1954 comic offered an alternative: ‘What punishment will you give an exploiter?’ one woman asks. ‘I will convert him into a woman – this is already easy – and send him to the market to suffer these prices!’ another responds (see Figure 9).Footnote 129 Carreño thus posited sex reassignment – and womanhood – not as self-actualising, but as fitting, burdensome punishment for those undermining food supplies. Once again, middle-class housewives symbolised public resentment towards economic malfeasance. Given ongoing social inequalities, transitions appeared a frivolous waste.

Figure 9. ‘Punishment’

Source: La Prensa, 8 May 1954.

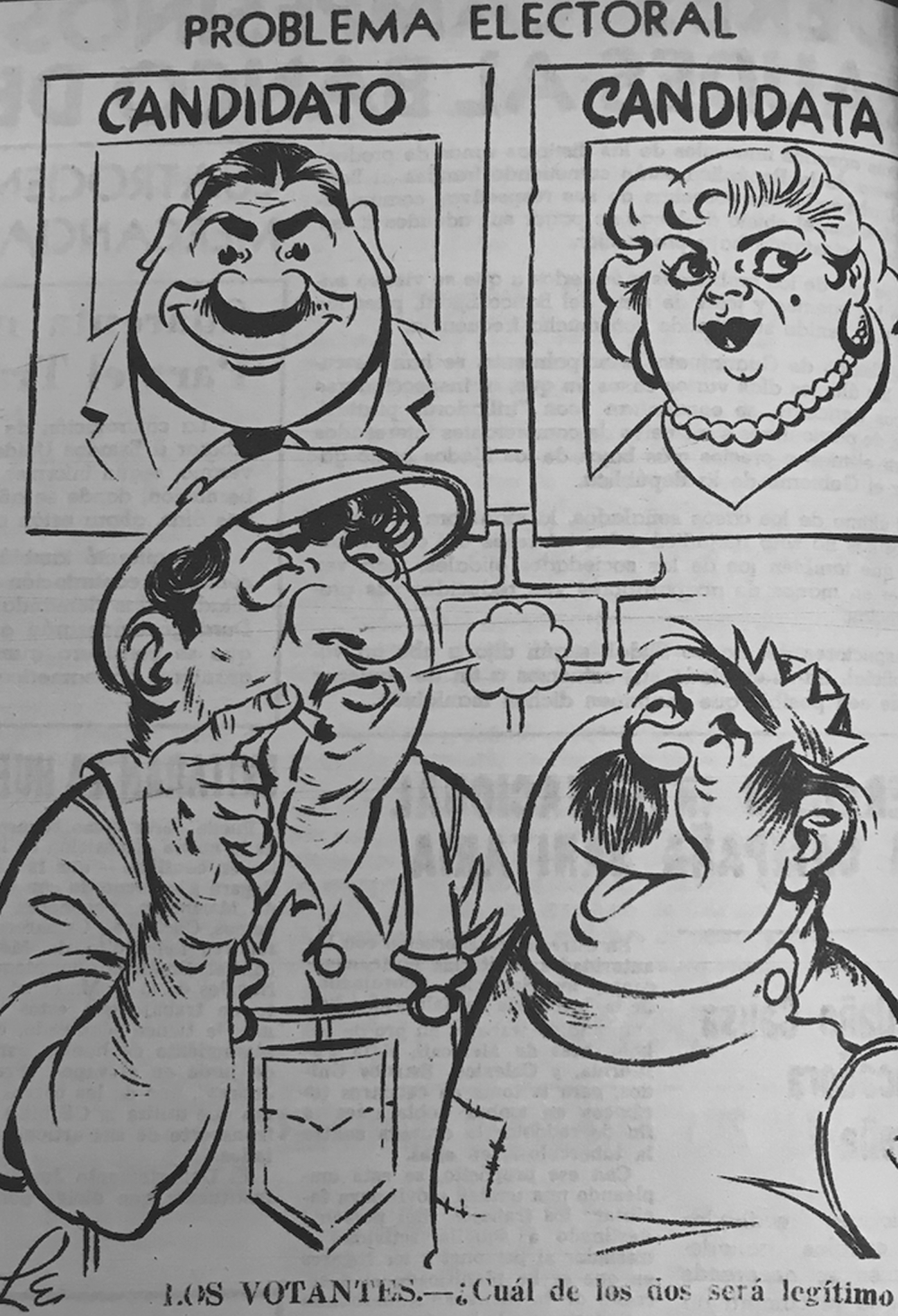

Carreño's satire highlighted a key legal issue: by transitioning, Marta punished herself by repudiating the status and opportunities maleness conferred.Footnote 130 Her rights would decline upon marriage in comparison to those husbands enjoyed. While she could still vote, given the recent success of women's suffrage, and seek office, her political legitimacy earned rebuke in an ABC cartoon depicting her as a candidate: ‘Which of the two will be legitimate?’ an everyman asks (see Figure 10).Footnote 131 The cartoon critiqued Marta, women's candidacies and the PRI's claims of progress: neither ‘candidate’ possessed legitimacy because neither was what they appeared to be.

Figure 10. ‘Electoral Problem’

Source: ABC, 10 May 1954.

Marta's case thus offered opportunities, initially, for social criticism and opposing censorship. Cartoonists challenged the socio-political status quo, while reaffirming gender norms. So too did columnists: poet Renato Leduc weaved political-economic threads through the Christine Effect, snarking in Últimas Noticias, ‘Already we have our Christine Jorgensen … What horror! Our national devaluation extends beyond monetary limits.’Footnote 132 Although refraining from attacking Ruiz Cortines’ administration directly, Leduc illustrated how critics implicitly smeared the state by evoking political concerns and rebuking the ‘morbid’ sensationalism surrounding Marta's case that besmirched national honour.

Global Marta

Marta's case, like Jorgensen's, garnered widespread attention in international discussions of sex reassignment. Beginning on 5 May 1954, US-based International News Service (INS) and United Press (UP) produced generally laudatory English-language wires and photos that appeared in papers big and small in several US and Australian states, Japan and Singapore.Footnote 133 Spanish-language papers in Los Angeles and Miami ran UP wires.Footnote 134 Hollywood's Variety labelled Marta Mexico's ‘local Jorgensen’. Australian Associated Press (AAP) wires tied Marta's publicity to Danish debates on banning transitions. Bogotá's Semana linked Marta to Jorgensen and Cowell, musing her transformation was impossible, like getting ‘pears from an elm tree’. Phoenix, Arizona's El Sol detailed conflicting reactions from Mexican physicians and public figures.Footnote 135 And in Ecos de Nueva York, columnist Felarca acknowledged Mexico's scientific achievement but warned against upending sex/gender social norms. So many men would seek transitions that, like in war, a population disequilibrium would result, ensuring a tyrannical future where ‘only skirts’ reigned, masculinity was annihilated and feminism triumphed globally. Felarca quipped: ‘Comrade, already science makes miracles that overwhelm, and changes peoples’ cables, like with machines!’Footnote 136

Marta's celebrity declined by summer 1954, but not because interest in transitions waned. Abroad, Jorgensen, McLeod and others diverted attention. In Mexico, publications stopped covering Marta but continued discussing Jorgensen. In September 1954, journalist Romay investigated ‘exploiters of Cristinas’ extorting homosexuals, but omitted mention of Mexico's own ‘Cristina’.Footnote 137 The Christine Effect meant afeminados – and those who transitioned – remained framed as foreign. The following March, weekly Siempre! summarised a sex-reassignment conference hosted by Ateneo Español genetics professor José Luis de la Loma; again, only Jorgensen featured.Footnote 138 Marta, reduced to an illustration, reappeared in US tabloid Whisper's 1955 exposé of medical tourism. Juan Morales quipped that soon ‘one of the most unusual travel ads since suitcases were invented’ would jolt readers: ‘Come to gay, colorful Mexico … Change sex while getting a sun tan! … Girls into boys and vice versa in 90 days …’ A sex-reassignment programme, Morales averred, ‘may soon become a completely open and above-board program, as well advertised as Mexico's celebrated sunshine’.Footnote 139 Morales again invoked the core dilemma: would transitions showcase scientific prowess or tarnish Mexico's reputation abroad?

Beyond Marta

Skidmore has argued US audiences discriminated against Marta because Jorgensen's international success and acceptance as a White, heterosexual, ‘authentic’ transsexual woman required the ‘subjugation of other gender variant bodies’ in racial terms.Footnote 140 For such audiences, Marta, grouped with other trans women of colour, was ‘dehumanised’, a lesser ‘Christine’ whose emulation solidified Jorgensen's archetypal authenticity. Certainly, even in Mexico, her intelligibility required Jorgensen as a referent – she was ‘Jorgensen's repetition’.Footnote 141 Yet, racial bias alone does not explain Marta's erasure in Mexico where her case had important implications for nationalism, patriarchy and the dictablanda. The choice was between two approaches, neither of which affirmed trans personhood, afeminados or those in the ambiente in their own right: (i) Sandoval's solution – conservative in premise but constructionist (assuming sex/gender liminality) and methodologically radical since it aimed to strengthen sex/gender binaries through surgery; or (ii) a culturally conservative alternative viewing sex/gender as static and associating homosexuality with foreignness, deviancy and subversion in need of punishment or erasure. Both viewed transitions as making physical the performative queer embodiment many afeminados expressed through feminine personas and behaviours.

For the minority following Sandoval, Marta was heteronormativised, her homosexuality surgically ‘cured’, the ‘natural’ sex/gender order stabilised, her femininity legitimatised rather than perverse, her true self ‘revealed’. ‘Saved’ from pathological degeneration, her anatomy, appearance and inclinations matched. She had doubly ‘migrated’: from Jorge, a role-playing, ‘deviant’, cross-dressing afeminado to Marta, a ‘normal’, heterosexual woman. Sandoval's solution was thus novel: transitioning queer men into normative (trans) women in an era when women enjoyed increasing socio-legal status. For decades following sodomy's decriminalisation (1871), authorities viewed those in the ambiente as ‘anti-social’ threats needing excision or rehabilitation.Footnote 142 Yet, neither public rebuke, police harassment, prison, exile nor ‘masculinising labour’, education or previous treatments worked in ‘solving’ the ‘homosexual problem’ because, unsurprisingly, queer Mexicans still existed. Concurrently, incremental progress on women's rights, while still enshrining a sex/gender binary, was central to modernising patriarchy. Legislation granted women suffrage, legal divorce and custodial, property, contractual and labour rights like those men enjoyed. Sex reassignment, Sandoval claimed, was an adjacent, if radical, move for rehabilitating homosexuals into ‘socially useful’ women-citizens.Footnote 143 Media representations, which Marta influenced, initially advanced this view, perhaps reflecting her self-image; such representations enabled her, like Robles and Jorgensen earlier, to positively craft her identity through a version of what Mary Kay Vaughan defined elsewhere as ‘modern spectator culture’ by interacting with and responding to the public through the media.Footnote 144

But the majority, despite including stakeholders interested in curtailing ‘plagues’ of afeminados and solving the ‘homosexual problem’, rejected Sandoval's solution and trans womanhood as a normative category of being.Footnote 145 For them, Marta's transition, contrary to Sandoval's intent, destabilised binary sex/gender and heteronormative, national patriarchy by duping people into thinking sex/gender was mutable. And, because it did not ‘cure’ male homosexuality, it expanded the ambiente. Approval withered before a broad consensus of physicians, politicians, journalists, cartoonists, prelates and others who championed sex/gender as unchangeable. Press coverage soon reinforced long-running tropes associating deviations from sex/gender norms with a foreign ‘third sex’, discursively ensuring those seeking transitions were deemed inauthentic. Without treatment, afeminados were poor female impersonators; with transitions, they remained inauthentic because congenital, biological sex determined personhood. Where did Marta, her ‘true sex’ contested, fit within an ongoing revolution that fashioned ‘new men and women’ socially while insisting on policing static, physical sex differences and specified gender roles?Footnote 146

In sum, trans womanhood was incompatible with state-building, distinguishing Marta from Robles, whose trans masculinity ‘simultaneously subverted and reinforced normative heterosexuality and the stereotypical masculinity it re-created’.Footnote 147 Robles reified patriarchy, thus could be accepted, while Marta – even when performing heteronormative femininity – could not because she undermined cisgender masculinity and femininity. Read through Octavio Paz's Laberinto de soledad (1950), queer Jorge had literally renounced manhood, patriarchal obligations and mexicanidad itself. Transitioning violated male bodies – even ‘deviant’ ones; ‘real’ men instead remained hermetically sealed while ‘tearing others open’.Footnote 148 Epitomising this view, Veracruz doctor Federico Gutiérrez argued in Excélsior that anyone transitioning ‘was nothing more than a eunuch’. Worse, Marta – incapable of biological motherhood – could not inhabit revolutionary womanhood; her desires for marriage and children made her a ‘wretch’ threatening to ‘stain women's most sublime condition: motherhood’. Sandoval's team deserved punishment; those seeking transitions deserved exile to the Islas Marías until their ‘maternal yearnings’ subsided.Footnote 149

Publicity also became problematic. Initial coverage garnering international acclaim might have lead supporters, including those in Ruiz Cortines’ orbit, to conclude Marta's case would deflect from domestic concerns. But critics soon argued Marta negatively influenced the public, while media outlets and Sandoval's team profited from sensationalism. As Gutiérrez put it, Mexico spent fortunes on ‘medical schools, clinics, hospitals and laboratories to teach our doctors to combat pain, to fight death, not for publicity's sake …’Footnote 150 Thus, reminiscent of reactions to the 1948 financial crisis, critics bludgeoned the dictablanda as misguided, even wasteful, during a period of public dissatisfaction, tying Marta's transition to government failings and questioning state development priorities. Such negative coverage eroded state support.

Concurrently, Jorgensen's story subsumed Marta's, obscuring any possible nationalist triumph: Marta just ‘impersonated’ Jorgensen, womanhood and Whiteness. Years later, postcolonial Filipinos and revolutionary Cubans saw Jorgensen's transsexuality and ‘spectacular whiteness’ as forms of US imperialism challenging national imperatives.Footnote 151 Many Mexicans felt similarly in 1954 because Marta's case evinced potential Mexican inferiority and encroaching US cultural imperialism. It drew unwanted attention to queer Mexicans just as the state ‘massified’ national identity for tourism and lucratively marketed Mexico as both modern (through technologies and infrastructure) and folkloric (through commodified culture).Footnote 152 By 1955, journalist Juan Morales claimed Cuernavaca was a ‘pansy paradise’ boasting ‘5,000 gay guys’ and ‘15 rebuilt maidens’.Footnote 153 Internationally, Jorgensen's case had ‘offered an exoticized travelogue for armchair tourists’ journeying ‘across the sex divide’.Footnote 154 Marta's case similarly positioned Mexico as where racialised, sexualised fantasies became reality.Footnote 155 Transitions promised ‘Tijuana-ization’, not modernisation, making Mexico a queer, colonised borderland where ‘Cristinas’ frolicked.Footnote 156 Unsurprisingly, Sandoval disavowed this touristic commodification.Footnote 157

Marta's case also threatened state relations with key constituents including the Church. From 1938, Catholic nationalism, predicated on binary sex/gender roles, infused state-promoted political-cultural mexicanidad against social models deemed ‘foreign to national reality’ – e.g. communism, Protestantism and US culture. But the dictablanda's politically expedient ‘modus vivendi’ with the Church had weakened by Ruiz Cortines’ presidency.Footnote 158 Prelates opposed transitions except in medically necessary cases of ‘true hermaphroditism’; otherwise, transitions further challenged this ‘national reality’. As such, for the dictablanda's nationalism – which amalgamated ‘true’ popular culture, modernised patriarchy and transnational development – Marta's case promised chaos, not scientific triumph. It further imperilled a useful political-cultural alliance. Catholics and conservatives were too valuable for the dictablanda's mid-1950s ‘hegemonic process’. And they supported moralisation campaigns bolstering state power.Footnote 159 These included raids against ‘centres of vice’ during ‘Iron Regent’ Ernesto Uruchurtu's Mexico City mayorship (1952–66).Footnote 160 Criticism of ‘foreign’ homosexuality featured thereafter in conservative rhetoric asserting Mexican moral superiority over the United States.Footnote 161

Thus, to ‘protect’ public morality, the state censored Marta, presaging later moves against threats to its power, moral authority and binary sex/gender system from students, youth culture and rock ‘n’ roll.Footnote 162 While authorities had prohibited Jorgensen from performing in Mexico, they did permit her films despite a 1951 law criminalising exhibitions ‘attacking morality’.Footnote 163 But growing public ‘disgust’ torpedoed Marta's own similar ambitions. Fernández Bustamante – director of Mexico City's Oficina de Espectáculos (Entertainment Office) – banned her from featuring in vaudeville revues, decreeing no ‘spectacle exploiting morbid interest’ would be tolerated.Footnote 164 Despite publicity otherwise, representatives from Rómulo O'Farrill's XHTV stated its ‘Tele-Síntesis’ programme would not interview Marta.Footnote 165 The Asociación Nacional de Actores (National Association of Actors, ANDA), led by Congressman Rodolfo Landa, refused her membership; ‘hermetically shut’ opportunities to all stage, radio or TV performances because she was not a ‘bona fide actor’; and denied industry-supported speech therapy.Footnote 166 Simultaneously, the phoniatrics department at José Gaxiola's Central Médica refused to treat her stubborn masculine timbre.Footnote 167 ‘Already those aspiring to be “Cristinas” and “Martas” … know there is no possibility of becoming famous’, columnist Raúl Cantú crowed.Footnote 168

Decreased press coverage also points to state censorship. Despite enjoying some autonomy, publications collaborated, perhaps to avoid irritating the state, which controlled access to paper and capital, and advertisers, who provided significant mid-century revenue.Footnote 169 Social critiques in cartoons disappeared by late May 1954; by June, even publications profiting from sensationalism ended coverage. Classism may have played a role: Marta was working class, while mainstream broadsheets catered to the middle class and elites. Pundits deploying ‘save the children’ rhetoric marked knowledge of Marta and transitions as outside ‘respectable’ conversation – and threatening to the nation's future. Even tabloids, facing negative public and government pressure, soon bolstered their readership's moral respectability and excluded trans individuals from their vision of mexicanidad. Marta's case was replaced by stories on foreign vice, Jorgensen, other trans individuals and ‘undesirable’ afeminados. Thus, unlike Skidmore has argued, racism alone did not diminish Marta's international coverage; instead, fewer stories published in Mexico, upon which foreign wire services relied, reduced coverage elsewhere.

Overall, the reception of Marta's transition involved a ‘double movement’: an ‘acknowledgement and a denial’ that ultimately ‘reject[ed] its relevance, knowing full well it occurred’.Footnote 170 Yet, in an example of productive political fence-sitting, the dictablanda refrained from prohibiting transitions outright. While some legislators and jurists clamoured to outlaw and punish transitions as akin to abortion, others sought to benefit and ‘steal Copenhagen's crown’.Footnote 171 Thus, the compromise: transitions continued without fanfare, but neither Marta nor Sandoval's solution were openly endorsed for political and moral reasons. Although Sandoval's book likely influenced subsequent transitions, it was self-published, suggesting a fall from political and professional favour. And Marta – recognised neither as normative man nor woman, considered foreign and lacking a constituency – could not symbolise Mexican modernity.

Nevertheless, Mexico continued attracting those seeking transitions. In 1955, Dixie McClane transitioned in Mexico City, perhaps at Alfredo Marinez's clandestine clinic near Avenida Reforma where for US$500 patients transitioned in three months through hormonal, psychiatric and surgical therapies.Footnote 172 Internationally known advocate Dr Harry Benjamin bolstered Mexico's significance before transitions occurred in the United States: when Denmark prohibited transitions for non-citizens, Hamburger (Jorgensen's physician) referred patients to Benjamin, who relayed them to Mexican physicians Jaime Caloca Acosta, David López Ferrer and José Jesús Barbosa until at least 1969. Benjamin's 1966 masterwork The Transsexual Phenomenon – which treated transsexuality not as a psychological disorder but a treatable somatic condition – and related correspondence also encouraged individuals worldwide, including Argentine Héctor Anabitarte and Pakistani A. J. Quraishi, to inquire about transitions in Mexico.Footnote 173 Nevertheless, despite such knowledge, none of the recipients were celebrated as ‘Martas’. She had been elided.

Marta's case also stoked continued public debate on how, and if, queer people could be incorporated into Mexico's national project. In his 1966 law thesis, José Antonio Ramos argued transitions validated homosexuals’ negative tendencies, harming rather than curing them.Footnote 174 In 1967, Argentine Emilio Federico Pablo Bonnet, writing in Criminalia, Mexico's premiere criminological journal, supported trans individuals, stating marriage should not be limited to the reproductively capable.Footnote 175 In 1969, Mexico City's Hospital Juárez denied Philadelphian Neilson La Bohnede's transition, citing sex's medical-legal role in personal identification. Changing sex, argued José Padua of Mexico's Health Ministry, violated Civil Code article 58, which stated sex was officially recorded on birth certificates.Footnote 176 Nevertheless, by allowing transitions generally, the dictablanda reconciled modernisation, expressed through contributions to global sexology, with preserving its nationalist sex/gender system. It benefitted from international awareness of Mexican science while mitigating sensationalism and criticism.

Since 2004, legislation in Mexico has made legally changing sex/gender (without requiring surgery) easier. Rather than rejecting trans people as anti-social – or seeking to ‘cure’ homosexuality – many Mexicans now accept their socio-political incorporation. Marta's case kindled this shift decades before Mexico's LGBTQ liberation movement, making global discussions on transitions relevant to Mexican identity, sex/gender norms, sexuality and personhood during processes of nation-building. How she felt about this and what happened after summer 1954 remain unclear; perhaps she wanted to disappear. However, a 1972 death certificate for ‘Martha Olmos Romero’, referencing her mother, Refugio, is likely hers.Footnote 177 If so, Marta died on 29 December 1972 from a myocardial infarction and twisted, occluded intestine. Though unmarried, she died as a woman under her chosen name, recognised by her doctors, undertakers and state agents alike. Whatever the circumstances of the certificate's production, Marta died on her own terms. ‘I wanted to be what I am’, she said after transitioning; ‘now, after the long-suffered treatment, I feel like a happy and normal woman’.Footnote 178

Acknowledgements

My grateful thanks to Howard Chiang, Emily Skidmore and James Welker for reading drafts and offering keen insights; to Ben Fallaw, Gladys McCormick, Anne Macpherson and Susan Stryker as well as JLAS editors and three anonymous reviewers for revision ideas; to Joshua Lupkin for finding the book that started this project; to the Archivo General de la Nación's staff who helped me locate Marta's photos; to SUNY Geneseo for research support; and to colleagues whose insights enlivened this work at the American Historical Association, Latin American Studies Association, and Sexology and Development conferences in 2018–19.