Word into Art

As an art-historical tradition, Islamic art begins in the late seventh century and continues until the late eighteenth century, encompassing art created in Muslim territories and for Muslim audiences, but not always in the service of the religion of Islam. The tradition waned during the modern postcolonial period as the Islamic world fragmented into sovereign nation-states. In its day, Islamic art was created in territories stretching from the Iberian Peninsula in the West, across North Africa, through the Arabian Peninsula, to Central Asia in the East. There are challenges to identifying the unifying features of such a long and geographically diverse art historical category. However, most agree on at least three features of this artistic tradition:Footnote 3

1) An absence of figural representation in the visual arts. The censure of figural representation in Islam was originally directed toward religious art, to prevent idolatry.Footnote 4 The desire to avoid figural representation then spilled over into the secular arts, which in turn led to a proliferation of art practices that lent themselves to non-figural decoration, such as ceramics and textile arts.

2) A love of surface decoration. Intricate vegetal and geometric patterns ornament the surfaces of every kind of object, from ceramics to carpets to mosques. Of note is the Islamic innovation of the arabesque, a flowing pattern of abstracted intertwining leaves and stems.

3) A veneration of script. Script may be used purely visually, as surface decoration for example, as well as for non-figural (symbolic) and even figural representation. Script is most commonly used to represent natural language and as such it can be used to add a layer of literal or metaphorical meaning to a work of art. The artfully written text of the Qurʾan, for example, is a pervasive and revered feature of Islamic art that is both decorative and meaningful.

A love of script endures among the contemporary artists who live and work in the remnants of the Islamic art world. An exhibition organized by the British Museum, Word into Art (2006), explored this legacy and the reinterpretation of script-based art practices in the contemporary Middle East.Footnote 5 As the exhibition catalogue explains:

The focus of this exhibition on the use of script in Middle Eastern art is not simply an accident of the British Museum's collection. It captures a powerful thread in the art of the region as a whole, encompassing beautiful calligraphy with its ancient roots, and the random graffiti of other artists. So important is this thread that a special term has been coined for it: hurufiyya, after the Arabic work harf, meaning “letter,” and alluding to the medieval Islamic scientific study of the occult properties of letters.Footnote 6

Hurufiyya denotes art that in some way uses script as a visual element in a work. I will refer to this as script-based art. This sort of art is found in the West as well, therefore the exhibition also explored whether and how script-based art reflects a regional aesthetic sensibility. Certainly, contemporary Arab and Persian Muslim artists draw upon traditional script-based practices in their own art. For example, in her photography series The Women of Allah (1993–97), a selection of which is featured in Word into Art, the Iranian-American artist Shirin Neshat uses script not only to represent specific texts by feminist writers and poets such as Forough Farrokhzad and Tahira Saffarzada, but also to visually reference the traditional female henna tattoo.Footnote 7 The photographs depict chador-clad women with texts inscribed on their exposed faces and hands in the manner of the traditional henna tattoo (the texts are actually inked onto the photographs). The script not only represents the prose and poetry of select writers, as well as visually references the henna tattoo, further it is used as a metaphor for the lived realities of the contemporary Persian Muslim woman, only able to say in art what cannot be said on the street. As I will show, the use of script and text in this way – to not merely say a metaphor but to be a metaphor – is distinctive of traditional Islamic art, and also of the work of the heirs to this art who live and work in the contemporary Arab-Persian art world and diaspora.

Script and Natural Language

Script as such does not have meaning, it simply represents a text that has a meaning. In other words, writing can be differentiated from natural language. A writing system inscribes or encodes and thereby represents a natural language. There is a large literature on how natural language has meaning, which I will leave aside to focus on script.Footnote 8 Most basically, writing, or any sort of inscription like a picture, might represent a subject either symbolically or mimetically. Writing typically represents a language symbolically, with letters and words that are connected to the linguistic sounds or gestures they represent as a matter of convention. Pictures represent their subject differently in that they actually resemble or look like what they are representing. There is an equally large literature on the nature of representation and the distinction (if any) between symbolic denotation and mimetic depiction, but most people intuitively grasp the difference between a symbol standing for something and an image that resembles something.Footnote 9

Concrete poetry, a Western art genre that originated in the Dada movement of the Weimar Republic, attempts both kinds of representation at once. It begins with a script of symbols, for example English, Farsi, or Arabic letters and words, which in turn represent a text with meaning. The poet then manipulates the script to also, at the same time, represent the text's meaning in a mimetic manner. The script in Apollinaire's concrete poem IL Pleut (1914) [Figure 1], for example, does two things: it denotes the text's meaning (“it's raining”), and also depicts the text’s meaning (picturing raindrops falling). Concrete poems, then, convey the meaning of a text in part linguistically, by representing the text symbolically with script, and in part visually, by manipulating the script in a way to also show us the meaning of the text. They are poems that must be seen and not only heard.

Figure 1. Guillaume Apollinaire, IL Pleut (1914). Typewriter, ink and paper. First published in SIC: sons, idées, couleurs, formes, no. 12 (1916): np. Reprinted in Guillaume Apollinaire, Calligrammes – Poèmes de la Paix et de la Guerre (Paris: Mercure de France, 1918), 62.

At times, a concrete poem can be so intensely visual that it is hard to decide whether it is a script-based or an image-based artwork. Consider the concrete poem After Weeks and Weeks in the Intensive Care Unit (c.1988) by the Lebanese-Armenian-Canadian poet Shaunt Basmajian [Figure 2]. The poem documents Basmajian's near-fatal experience while working as a taxi driver in Toronto, when he was robbed and stabbed with a knife in his right lung. The script does two things: first, it gives us a text, notably the concluding “a gasp” that is the simple but exasperated act of breathing again, and second, it is used to depict hospital gauze and a punctured lung. Although the poem is highly visual, the centrality of script and typography in conveying the meaning of the poem distinguishes it as a concrete poem.

Figure 2. Shaunt Basmajian, After Weeks and Weeks in the Intensive Care Unit (c.1988), typewriter ink and paper. Reproduced in Shaunt Basmajian and Brian David Johnston, eds., Bfp(h)aGe: An Anthology of Visual Poetry and Collage (Toronto: Sober Minute Press, 1989), 59.

Script-based art, which includes concrete poetry, can be distinguished from word-based art, a near neighbor but not quite so fixated on exploiting the intrinsic features of script to convey poetic meaning. Consider here French artist Laurent Grasso's installation The Wider the Vision, the Narrower the Statement/Kullama Ittasa‘at al Ru’ya Dhaqat al Ibara (2009).Footnote 10 The phrase “the wider the vision, the narrower the statement,” attributed to the tenth-century Sufi writer Muhammad Ibn al-Niffarī, was rendered in blue neon, 3 meters high and 27 meters long, in Arabic, and was installed along a narrow corridor in a historic house as part of the 2009 Sharjah Biennial. Depending upon where the viewer is forced to stand in relation to the work the text appears wider or narrower, bringing about a heightened awareness of the very act of reading the text. The artwork, however, does not rely upon the intrinsic features of the script, its typography and the neon material, to convey this meaning. Instead, the work relies upon the relational features of the script, its placement and scale, to convey the work's meaning. There are three distinct elements in Grasso's work: the script (lettering) which visually represents the sounds used to speak the text; the text itself (“Kullama Ittasa‘at …”); and the work, which uses the text and its placement toward the end of making a comment on the act of reading. Whereas script-based art places emphasis on the script toward the end of creating a work, word-based art places the emphasis on the text. Script-based art, then, is distinguished by a love of script as such, not merely as a vehicle for representing a text, but for its intrinsic decorative and metaphoric value.

Abstraction and Revelation

Artists of the Islamic world were not only fascinated with script, but more expansively with the abstract, the non-figural, and with metaphor. Often artists would use script formally in the service of metaphor. For example, in an architectural roundel from the late sixteenth century, the words “Ya ’Aziz” (O Mighty) are mirrored and repeated within the roundel shape, both stating and showing the idea that God is a pattern reflected in all things [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Calligraphic Roundel. c. late sixteenth, early seventeenth centuries. Sandstone and pigment, 1 3/16 in. high x 18 1/2 in. diameter.

More abstract yet is the genre of pseudo-inscription, which uses Arabic script to decorate a surface, a common enough practice, but in this case the script is made-up, it does not represent a natural language or text. Still, while these inscriptions have no linguistic (semantic) meaning, they nevertheless have mimetic meaning as an image or depiction of written language. As Don Aanavi comments, these inscriptions “reflect a thoughtful and enormously sophisticated attitude toward the significance of writing. . . what we may not understand is not, by consequence, meaningless.”Footnote 11 It is possible to abstract further yet, from script altogether to sheer pattern in art. Like pseudo-inscriptions, pattern does not have semantic meaning but it nevertheless has metaphoric meaning in representing logos as abstract yet present in all things.Footnote 12

Pattern and light are potent aesthetic devices in Islamic art. Whereas pattern is a representation of logos, light in Islamic art is often used as a metaphor for revelation. In Islamic architecture, for example, direct and reflected light is not only used to reveal colour and form, but also as a metaphor for the removal of ignorance as the viewer gradually comprehends the architectural work.Footnote 13 An especially potent aesthetic device in Islamic art is the rendering of pattern in light. The work of the French architect Jean Nouvel, not himself an heir of the Islamic art world but who has created works for the contemporary Arab art world, exemplifies the entwining of pattern and light in architecture. In the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA), completed in 1987 in Paris, Nouvel used the mashrabiya, a lattice screen commonly used in Islamic architecture for shade and privacy, toward this end.Footnote 14 The south façade of the IMA is a lattice of automated apertures that open and close like the shutter of a camera or the pupil of an eye, to control the intensity and patterning of the light illuminating the interior of the building. Similarly, Nouvel's Louvre Abu Dhabi (2017) in the United Arab Emirates is capped with a dome of layered lattices that allow a soft rain of light to fall within the interior, at once revealing and protecting the artworks housed within.Footnote 15

Indeed, a recent exhibition at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, Abstraction and Calligraphy: Towards a Universal Language (2021), explored the entwining of script, pattern, and the abstract in art. The exhibition traced the resonances between calligraphic practices found in the Islamic and Far Eastern worlds and twentieth-century Western abstractionism.Footnote 16 Each in their way, these artistic traditions entailed experiment with “pictograms, signs, symbols, lines, and other traces of the hands of the artists” in the search for a “universal language.”Footnote 17 While script-based art is rooted in the concrete (visual) markings of script, it is nonetheless an abstract art inasmuch as it brings abstracta – mental objects such as literal and metaphoric meanings – into focus. As the exhibition curator Didier Ottinger comments, the abstractionists saw in calligraphy “a non-figurative art that was nonetheless anchored in meaning [which] could avert the danger of the purely decorative that has always threatened abstract painting.”Footnote 18 In other words, the abstractionists appreciated calligraphy as something like pseudo-inscription, concrete markings that are obliquely representative of meaning.

The exhibition was not only about abstractionists looking to the traditions of calligraphy, but also about contemporary artists in the Middle East looking to abstractionism, both East and West. For one thing, these contemporaries share with the artists of the Islamic world an interest in loosening art practices like calligraphy from their utilitarian ends, which, in the case of calligraphy, is to represent a text with precision and clarity, to expand their use for artistic ends. In Perception (2016), for example, the Tunisian-French artist eL Seed stencilled a calligraphic rondel across the façades of approximately fifty stacked houses in a marginalized Coptic neighbourhood of Cairo [Figure 4].

Figure 4. eL Seed, Perception (2016). Exterior house paint, housing complex, Manshiyat Naser, Cairo. View from Al Mokattam Mountain.

At street view the rondel is fragmented, and it can only be seen as a coherent design from Al Mokattam Mountain overlooking the neighborhood, at which point the fragments fall into place to read “anyone who wants to see the sunlight clearly needs to wipe his eye first,” an adage attributed to a third-century Coptic bishop. Even at the correct viewing point, the clarity of the text is purposefully disrupted by the irregular façades. This is both a script-based and word-based artwork, drawing upon the intrinsic features of the script, rondel and fragmented, as well as the relational, site-specific installation of the text, to make its point.

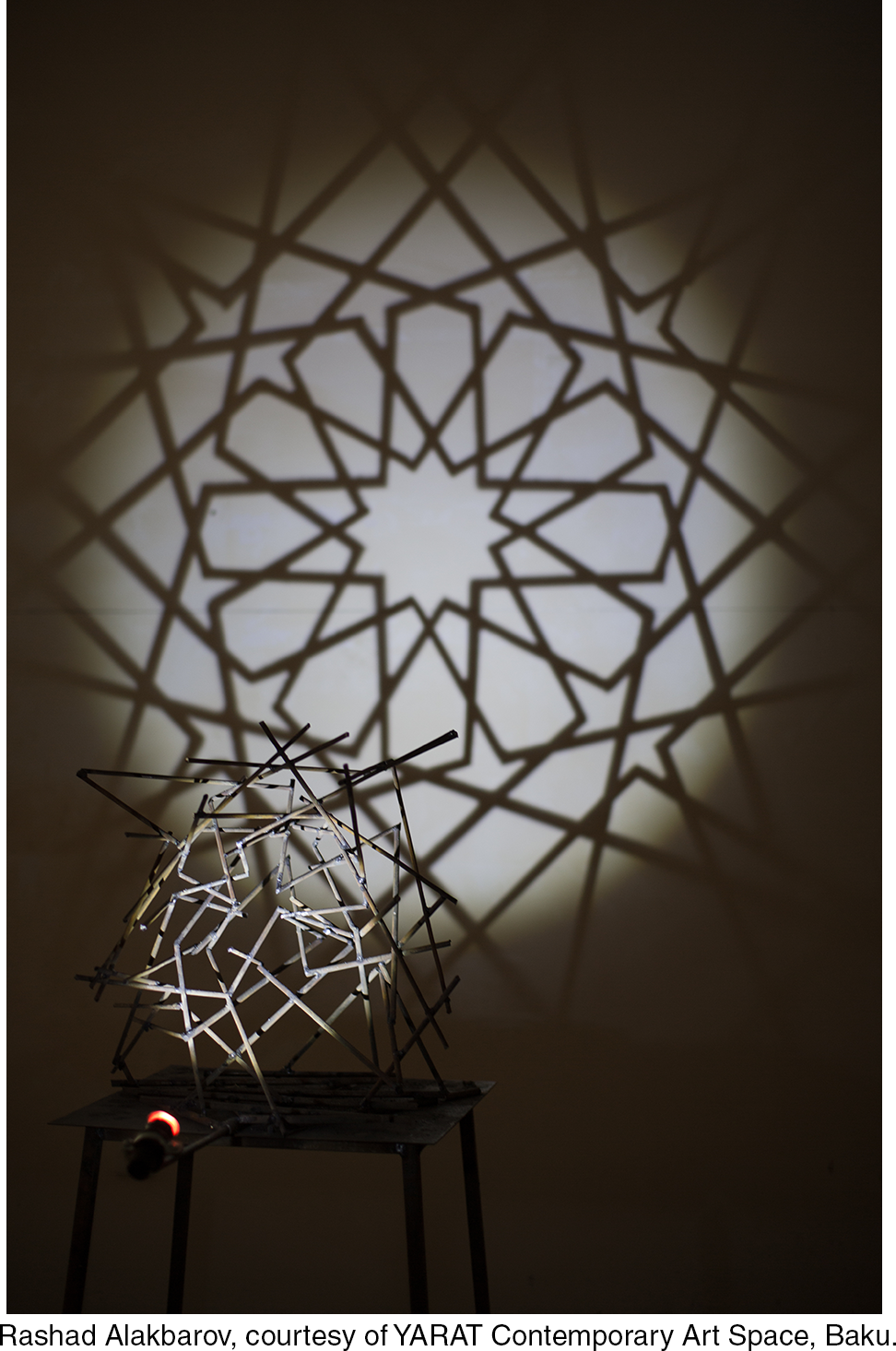

Artists in the region also draw upon the methods of abstraction in their reinterpretation of traditional art practices. In Shebeke (2017), for example, the Azerbaijani artist Rashad Alakbarov references the shebeke, a screen for privacy and light found in traditional Azerbaijani architecture [Figure 5]. (Not in the Louvre exhibition, earlier versions of Shebeke have been exhibited at the 2012 Sharjah Islamic Art Festival and at the 2013 55th Venice Biennale).

Figure 5. Rashad Alakbarov, Shebeke (2017). Welded iron and spotlight. Installation view at YAY Gallery, Baku.

Like the mashrabiya, the shebeke is a lattice structure, but the openings are filled with coloured glass. It is typically built into an exterior wall allowing colored, patterned light to fill an interior. Alakbarov's sculpture is not literally a shebeke, nor is it a reinterpretation or application of an architectural element along the lines of the Louvre's dome. Alakbarov’s work is not a utilitarian use of the shebeke at all. Rather, it is an abstraction, showing us the shadow or effects of the shebeke. It can be appreciated not only as an artful representation of an otherwise utilitarian object, but also as a metaphor for how light reveals form and thereby brings about perception and understanding. The patterned shadow is an abstract script, if you will, that conveys meaning metaphorically.

A Metaphor of Metaphors

Victor Stoichita traces the element of shadow in art to origin myths in Pliny and Plato.Footnote 19 Pliny tells an origin story of painting in his Natural History, when a maid traced the outline of her beloved's shadow on a wall. Plato tells a darker story of art in his Republic, as originating in deception, not love or truth. Like shadows cast onto the back wall of a cave, art is the mere shadow of reality, not reality itself, which can only be found outside the cave in the sunlight. Whether an act of love or deception, shadow art such as Nouvel's Louvre dome and Alakbarov's Shebeke are metaphors for art's origins in shadow and light.

As in the case of concrete poetry, metaphor contrives to do two things at once, in speaking of one thing in terms of another. For example, the expression “the dark night of the soul” speaks about self-doubt in terms of a dark night. In Western scholarship, up to about the nineteenth century, metaphor was thought of as a rhetorical embellishment found primarily in the literary arts. It was even discouraged as a distraction in otherwise sensible prose. However, metaphor is pervasive in everyday speech and prose, and it would be self-defeating to avoid all use of metaphor. By the twentieth century, metaphor came to be viewed as not merely an incidental literary flourish, but as central to how language, and perhaps thought itself, works. The rehabilitation of metaphor began with linguists attempting to state how a metaphor has semantic meaning. A speaker uses a literal meaning in a nonliteral, figurative sense, but it is difficult to say how words and phrases might have a nonliteral, deviant meaning in addition to their literal meaning. Donald Davidson suggested that we simply concede that a metaphor means, semantically, nothing more than its literal meaning.Footnote 20 There is no additional deviant meaning. What metaphors do, however, Davidson concluded, is generate novel ways of looking at and thinking about the world.

There is lingering debate within the field on how metaphors mean. Be that as it may, there is a growing recognition of the centrality of metaphor to language and thought. It pervades how we speak about and understand the world. George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue that to speak or hear a metaphor is fundamentally a thought process wherein we map concepts from one domain onto another, creating correspondences that help us make sense of the world.Footnote 21 Building on this, Eva Kittay points out that a metaphor does not create something entirely new, such as a deviant semantic meaning, but rather reconfigures what is “already available to us” to then “access” what is less available or obvious.Footnote 22 We reconfigure the known, the concrete, to access the abstract or even the unthinkable, like the concept of nothingness. Unsurprisingly, metaphor has always been central to religious and philosophical writing. One can also see how both script-based and shadow art, which entwine concrete and abstract features in a manner suited to the creation of metaphor, is appealing to artists drawn to religious and philosophical thought.

A work of art that exemplifies the nature of metaphor is Heech in a Cage (2005) by the Iranian-Canadian artist Parviz Tanavoli, featured in the exhibition Word into Art and found in the British Museum collection [Figure 6]. Over the years, Tanavoli created a series of sculptures based upon the script for the Farsi word heech, which means “nothingness” – the ultimate abstraction. The thirteenth-century Sufi poet Jalal al-Din Rumi wrote that the concept of heech, from which God created everything, is inherently divine. Tanavoli captures the abstract, divine concept of heech, casting it in an alloy metal symbol, and putting it in a bronze cage for good measure, to create a metaphor for creation, indeed for metaphor itself, as an arabesque of concrete and abstract features that, as Kittay would put it, invite us to cognitively reconfigure what is available to us to access the less obvious. All said, script qua aesthetic device in Islamic and contemporary Arab-Persian art is not merely decorative, though it is that too. It is moreover a cognitively faceted device, generative of art, and it continues to animate the aesthetic sensibilities of contemporary artists in the region.

Figure 6. Parviz Tanavoli, Heech in a Cage (2005). Cast bronze, 118 cm. high x 49 cm. wide x 42 cm. deep.