When I explained the premise of this article to a friend and colleague, she held my arm, looked into my eyes, and solemnly whispered: “I would not write about Monster Truck.” From the outside, Berlin’s theatre scene appears to have a boundless appetite for putting the obscene onstage; in my years as a critic, I witnessed simulated fellatio and live fornication, vomit, blood, and urine. Yet there is in fact still a real taboo in the contemporary German theatre: stepping away from viscera and meditating on surfaces.

Figure 1. John Lakutu of The Footprints of David youth dance company from Lagos, Nigeria, in the pose of Alan Kurdi, the drowned three-year-old Kurdish boy — an image that has been recreated and remediated ad infinitum. Sorry by Monster Truck and Footprints of David/Segun Adefila. Sophiensaele Berlin, 19 May 2016. (Photo by Florian Krauss; courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

In many ways, Monster Truck seems to be very similar to other Freie Szene (independent arts community) ensembles. Marcel Bugiel, Manuel Gerst, Sahar Rahimi, and Ina Vera met in 2005 while studying at the Institute for Applied Theatre Studies in Giessen; their dramaturgy smacks of both Homi Bhabha and Jean Baudrillard. Monster Truck’s artist statements and interview quotes are prime for academic analysis; no coincidence, given the focus on critical theory in Giessen’s curriculum. Such a combination of theory and practice is otherwise rare in Germany, with its strict division between Theaterwissenschaft (academic theatre studies) and conservatory training.

Like many other Freie Szene groups coming out of Giessen, the Monster Truckers play for young audiences or those “young in spirit” (Brauneck 2017:15). Like other independent scene groups, Monster Truck works collaboratively with other artists and ensembles project by project. They present their work in Freie Szene venues and tour European festivals. Monster Truck is interdisciplinary, working between theatre, dance, and visual art in a mix that cannot be described in German and is therefore simply, in English, “performance.”

But Monster Truck has one critical difference from similar groups: their body of work systematically undercuts the concept of the authentic, instead staging painful stereotypes through densely packed dramaturgies of double meaning. They perform inequalities of power: between disabled and abled people, between actor and director, between white audience members and black performers, between Europe and Africa. Indeed, looking at the work of Monster Truck reveals the extent to which the rest of the German independent scene, including the documentary and postmigrant theatre movements, relies on the concept of “authenticity,” its production and reproduction effectively obscuring the workings of power.

Monster Truck is a relatively heterogeneous group in terms of ethnicity, ability, nationality, and career interests. But it feels reductive to describe the members of Monster Truck in this way, because this is not how they describe themselves. Unlike other German independent scene artists who are not white, able-bodied Germans, the members of Monster Truck do not foreground their identities. By creating distance between their lived experiences and the work they put onstage, Monster Truck stands apart from an independent scene that is very much interested in collapsing identity and art into a unified “real.” Monster Truck leans into the fictional rather than the factual, staging what we already know — the stereotype — rather than introducing us to the stranger.

As a result, they are in many ways personae non gratae. Their performances have been protested, accompanied by panel discussions, and canceled (see Theater der Zeit 2015). Their work has also received little sustained critical attention compared with many of their Freie Szene peer groups. Which is a shame, because Monster Truck’s performances are doing complex cultural work not only within critical race discourse in Germany but also around issues of authenticity and theatricality more broadly. I turn to their 2016 performance Sorry, which premiered at Sophiensaele Berlin and was coproduced by The Footprints of David, Theater Rampe Stuttgart, Forum Freies Theater Düsseldorf, and the Goethe-Institut Nigeria.

What could I say in response to my colleague’s warning? I wasn’t sure. Am I jeopardizing my career by writing about Sorry? Or my reputation in solidarity with Germans of color? Isn’t Monster Truck’s director and often spokesperson Sahar Rahimi a woman of color? Am I not, myself, often racialized in Germany? Every question raised by Sorry multiplies so quickly into a handful of related questions that it’s hard to find a stable place from which to speak. Where should I begin? Let’s start with an apology. Friend, if you’re reading this: I’m sorry.

African Alan Kurdi

Monster Truck’s Sorry opens with a familiar image — a brown boy lying on the ground face down on a white stage floor. We are looking at a live embodiment of the famous photograph of Alan Kurdi, a drowned three-year-old Kurdish boy on the beach at Bodrum, Turkey. Taken by Nilüfer Demir in September 2015, the photo “forced Western nations to confront the consequences of a collective failure to help migrants fleeing the Middle East and Africa to Europe in search of hope, opportunity, and safety” (Barnard and Shoumali Reference Barnard and Shoumali2015). Kurdi’s clothing — his red shirt, blue shorts, and little sneakers — generate the affective power of the image; Footnote 1 onstage, we see instead a black boy, older and much larger than Kurdi, wearing only his white boxer briefs. He is John Lakutu, a member of the Nigerian children’s dance company from The Footprints of David, a Lagos-based arts academy and social enterprise for disadvantaged children led by Sorry’s codirector, choreographer Segun Adefila; they were invited to Berlin for the performance. Lakutu is not on the sands of Bodrum but at Sophiensaele, an independent dance and performance venue in Berlin. By 2016, the image of Kurdi had already been subject to countless “memetic remediations” (Durham Reference Durham2018:247), from internet memes to artistic interventions, such as Ai Weiwei’s provocative recreation of the photograph, in which he substituted himself as the subject of the image (India Today Reference Today2016).

In her article “Resignifying Alan Kurdi,” Meenakshi Gigi Durham demonstrates the ways in which the original photograph creates an ethics of care by showing Kurdi’s embodied vulnerability. The reproduction of this image as a meme multiplies the image’s semantic possibilities and social functions. Monster Truck’s remediation — staging this image live in front of an audience — is exponentially polysemic and politically opaque. On the one hand, choreographing a live child as a stand-in for a dead one is a return to the empathetic imperative generated by the original image. Nearly unclothed onstage, the body is all the more present, all the more vulnerable. Embodying the image shows the power of live performance to make transparent and urgent the ways in which colonial relations land on the body.

In other ways, switching the bodies of Alan Kurdi and Nigerian dancer John Lakutu brings our attention to the substitution itself, the technê of the meme: “An oppositional reading of this meme could perceive an ironic riff on the callousness of the West’s response to the tragedy” (Durham Reference Durham2018:253). Yes, there is in Monster Truck’s reproduction more than a little callousness. In Sorry, Kurdi is fungible. The Monster Truckers demonstrate that they can substitute a briefs-clad boy for a clothed one, an older child for a toddler, and, most tellingly, a Nigerian child for a Syrian one. A still image of this moment of the performance was for a long time splashed across the landing page of Monster Truck’s website: clearly, the tension between the callous, joking repetition of the meme and the “embodied vulnerability of the child” is key to the group’s brand.

Confronted with a parodic, or at least memetic, reproduction of the death of a child like this, the viewer of Sorry faces what is perhaps the singular question of recent years: Is it good — in the moral sense. Wesley Morris updates a classic question about the relationship between text and context in a long manifesto in the New York Times Magazine titled, “The Morality Wars.” Morris writes, “We’re talking less about whether a work is good art but simply whether it’s good — good for us, good for the culture, good for the world […]. The goal is to protect and condemn work, not for its quality, per se, but for its values” (2018). As Nicholas Ridout addressed the morality issue nearly a decade prior in Theatre & Ethics, “There is [among contemporary theatre artists and critics] an expectation that the aesthetic will be a pathway toward the fully ethical” (2009:65). Even as the audience files into the space in sight of this embodied meme, Sorry immediately confronts the viewer with the morality matrix that Morris and Ridout describe, by which art is judged to be “OK or not OK,” “woke or canceled.” I wondered, “Can they do this? Should they do this? Is this OK?”

Monster Truck Is Canceled

The images that Monster Truck put onstage are not OK. Their most controversial work, Dschingis Khan (Genghis Khan, 2012) cast Mongos as the Mongolians. In German, “Mongos” is a derogatory term for people with Down syndrome, based on the 19th-century scientist Langdon Down’s perception that people with Down syndrome shared racialized facial features with “Mongols” (Down [1866] 1966:697; see Tong Reference Tong2021). Sahar Rahimi explains,

Figure 2. Sabrina Braemer, Oliver Rincke, and Jonny Chambilla telling jokes and generally fooling around in an improvised scene in Genghis Khan by Monster Truck. Forum, Freies Theater, Düsseldorf, 19 September 2012. (Photo by Ramona Zühlke; courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

We thought about doing a piece about different autocrats, Caesar, Napoleon, and we came to Genghis Khan, the leader of the Mongolians. And someone said, if we do Genghis Khan, we have to cast Mongos. We all laughed terribly: it was very late at night. And then we thought, why should we laugh? What’s behind this? (Rahimi Reference Rahimi2013) Footnote 2

I understand my friend’s warning against laughing along with such a cruel joke. Genghis Khan is staged as a human zoo — more politely, ethnological exposition, the German Völkerschau. These expositions of nonwhite people in Germany presented as colonial objects continued well into the 20th century. The production suggests that although European society has (recently) moved beyond crass ethnological exhibits of live people, the commodifying and exoticizing modes of looking typified in the Völkerschau live on. And yet this theatrical technique of restaging subjugation to open a topic to critique risks doing more harm than good.

Does it matter that the dramaturg, Marcel Bugiel, has a long-standing relationship with the three performers with Down syndrome? Does it matter that the company members are themselves minoritized? Does it matter that Sabrina Braemer, Jonny Chambilla, and Oliver Rincke are all professional, trained actors working in the repertory company Theater Thikwa? To ask these questions is to participate in the mode of contemporary art criticism that Morris describes: a calculation of the piece’s values, weighing potential empowerment against potential hurt and offense.

Someone formally defending the work might stress its raw theatricality, drawing into question the mechanics of theatre-making itself. Monster Truck demonstrates the power difference between those with Down syndrome and those without through the metaphor of theatre, putting the directing process itself onstage. Footnote 3 Not only in Genghis Khan but in all of Monster Truck’s productions, power dynamics onstage raise broader questions about power dynamics behind the scenes and more broadly. As the artists explain in an interview, the central questions for Monster Truck are: “Who tells whom, what he must do? And why?” (Gerst, Schröppel, and Sobottka Reference Gerst, Schröppel and Sobottka2018:3). But I don’t want to make the argument that Genghis Khan is OK. It’s not.

Figure 3. Sabrina Braemer in Dschingis Khan by Monster Truck, trying to “kill” herself, instructed by voiceover from Sahar Rahimi. Forum, Freies Theater, Düsseldorf, 19 September 2012. (Photo by Ramona Zühlke; courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

But mostly, I fear that this mode of criticism (woke or canceled) arrives only at an impasse. The hall-of-mirrors effect created in Monster Truck’s ever-backwards search for and parody of “authenticity” is a more generative site for analysis. In Genghis Khan, Rahimi played a condescending director who bosses around the actors playing Mongolians, which led to a series of questions in print as well as in panel discussions about whether the actors with Down syndrome were “really” being subjugated. Some audience members proposed that inclusivity in theatrical leadership would neutralize this jarring inequality between neurotypical director and neuroatypical performer.

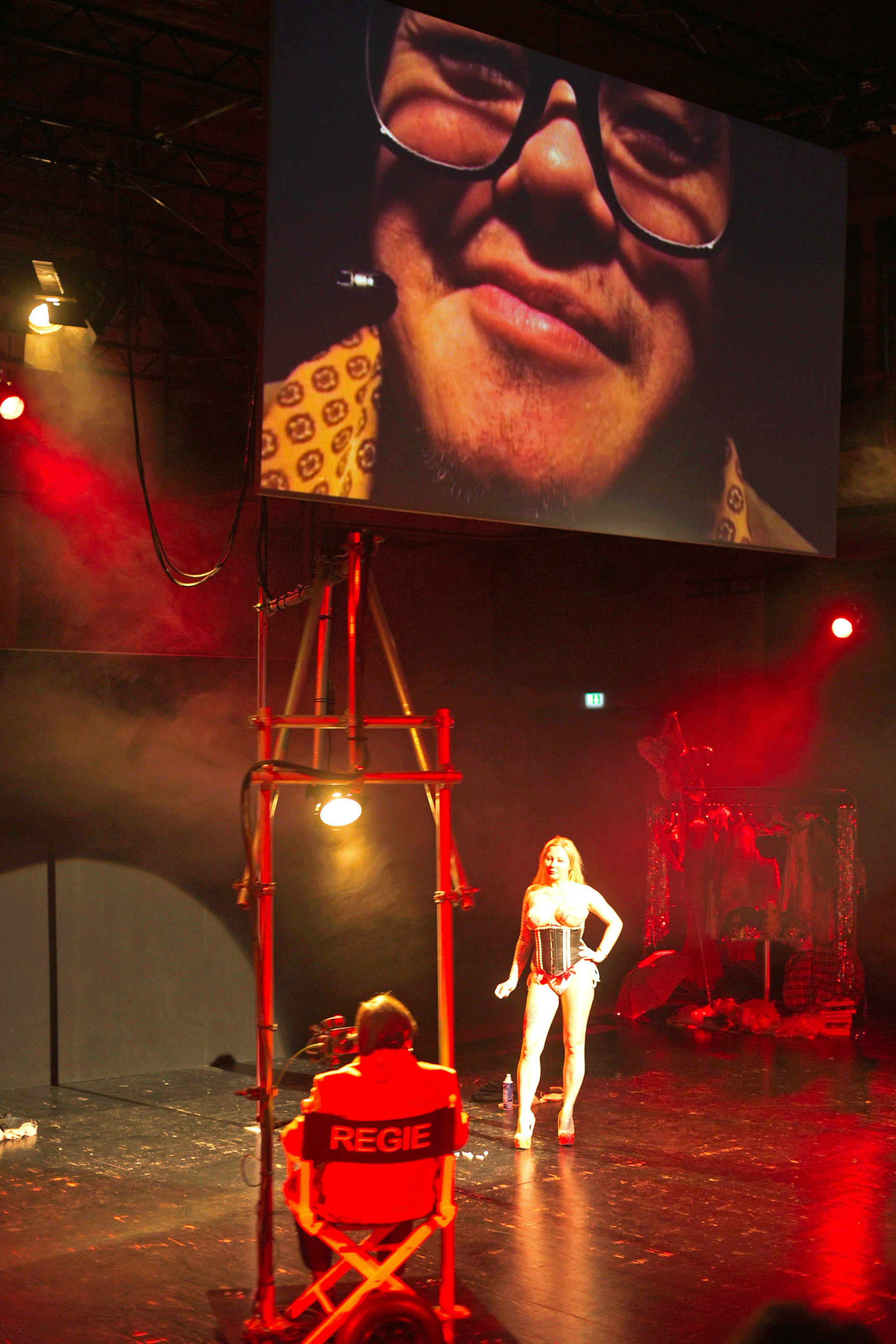

However, rather than neutralize this inequality, Monster Truck further showcased the problems of consent and control onstage. They created another performance, Regie (Director, 2014), in which the Genghis Khan actors with Down syndrome devised the performance and are credited as the directors. Sabrina Braemer dresses up audience members for a selfie, then directs the entire audience in a collective dance. Jonny Chambilla directs a striptease, his face superimposed on a big screen above a stripper pole and a porn actress with tattoos and huge breasts. When she takes her bra off, a wide smile spreads across Chambilla’s face. He licks his lips. When her striptease has ended, Chambilla murmers, “Sehr gut, danke, sehr gut. Affen machen.” (Very good, thank you, very good. Now humiliate yourself; Affen machen translates directly as “play the monkey”) (Monster Truck Reference Truck2014). But the actress (Elysia Sky) crosses her arms over her naked chest and shakes her head: no. Actors are not objects but agents, Monster Truck suggests, spoofing the audience’s paternalism toward theatre-makers with cognitive disabilities. But also, the group seems to add with an ironic wink, even directors are beholden to the audience, to the institution, to their funders. Who is really in control here? The question has no answer.

An anonymous commenter on the German theatre blog Unruhe im Oberrang called Regie “a betrayal of the theatre” (in Gmeiner Reference Gmeiner2014). I assume he meant this as an insult to the work’s crassness, but the phrase is apt. Regie indeed does betray the central conceit of the German Regietheater: that a solution to the problems of Genghis Khan would be to promote the disabled actors to the more powerful position of director. Regie demonstrates that simply putting more marginalized people in positions of power did not alter but instead amplified the problem of power relations immanent in theatre-making — that someone is always telling someone else what to do, that someone is always displaying someone else, pretending that it’s real.

Figure 4. Jonny Chambilla “directing” Elisia Sky in Regie by Monster Truck. Sophiensaele, Berlin, 16 April 2014. (Photo by Ramona Zühlke; courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

In 2015, Monster Truck created a follow-up to the follow-up, Regie 2 (Director 2), in which titles flashed across the scrim: “We don’t want to talk about directing any more. We’d like to take you to a different performance, with a different director.” I had just begun working as a theatre critic at the time of the premiere and was excited to weigh in on these issues with my coverage of the No Limits theatre festival. My notebook was still blank as we were instructed to gather our coats and bags and board a chartered bus. We went to an ice hockey match. In the collective’s own words, Regie 2 “takes this concept of transference of artistic responsibility to the extreme” (Monster Truck Reference Truck2015). Other nights, I later learned, Monster Truck delivered the bus to an opera, and a conservative German-language family drama. I was disappointed.

Looking beyond Genghis Khan to these performances in sequence, one sees not the explosive deployment of crude stereotypes for shock effect but rather a systematic examination of power relationships in the theatre and beyond. Rahimi clarifies the principle of Monster Truck’s reflexive dramaturgy in a video interview: “Yes, we are exhibiting [the actors with Down syndrome], and we are also exhibiting ourselves exhibiting them” (Weigel Reference Weigel2012). Moreover, Monster Truck suggests that there is no way to refuse this recursive, metatheatrical process: their “attempt” to transfer responsibility in Regie 2 seemed designed to fail. Implicit in this body of work is a critique, I think, of other performances that do not draw the politics and ethics of the representational process into question as Monster Truck so insistently does. It strikes me that Monster Truck is fundamentally antitheatrical — in the sense of distrusting and disrupting the very concepts of “acting” and “directing” — and deeply invested in the transformative power of spectacle.

Even the ensemble’s name is bitterly ironic, both referencing and refusing the over-the-top, populist theatricality of a monster truck rally.

Our name stands for the desire for spectacle and at the same time the critical scrutiny of this desire. Isn’t the promise of some sensation always greater than its realization? We found the difference between an advertised bombastic [monster truck rally] and the sad reality of a dirty, rained-on parking lot so cool, in a melancholy way, that we gave our group this name. (in Gerst, Schröppel, and Sobottka Reference Gerst, Schröppel and Sobottka2018:3)

If the ironic doubleness of Monster Truck’s name, dramaturgy, and scenography is dizzying, it is also a form of critique. Monster Truck poses an aesthetic argument for multiplicity over the singularity and self-sameness implied by authenticity.

Figure 5. Sabrina Braemer “directing” audience members in Regie by Monster Truck. Sophiensaele, Berlin, 18 April 2014. (Photo by Ramona Zühlke; courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

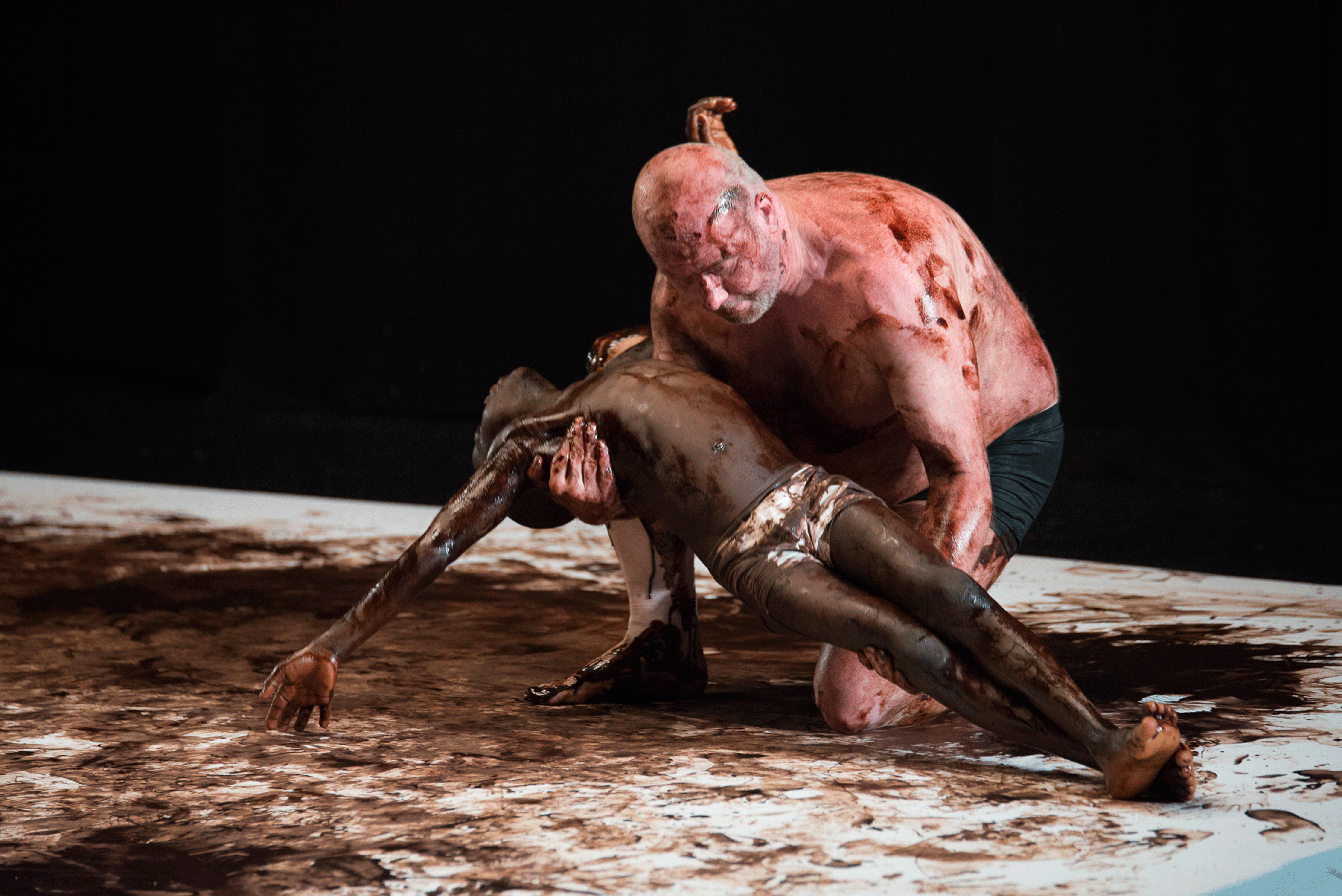

In Sorry, the static image of Alan Kurdi multiplies into more complicated, slipperier configurations. Andreas Klinger enters: a larger, white German in a white dress shirt, black dress pants, and, somewhat surprisingly, a yellow scarf. He sits facing the Kurdi figure and eats a whole chocolate bar (Ritter Sport mit Cornflakes!), licking his fingers with satisfaction. He kneels down to pick up the boy and holds his limp and nearly naked body in his arms. It’s a kind of pietà, and scenically beautiful; the full weight of this symbolic gesture immediately resonates. But this image, too, embodies its own critique: the European cradles the dead African, but we also understand the irony — that this is a trope we expect. It is embarrassing to be confronted with a series of images confirming our prejudices about this black body, this white body, and how they relate to each other.

The moment that follows again turns the tables. After a moment in this pose, the boy springs to life as though possessed, twitching, going for the jugular. Or is it an embrace? Their faces are close together — it is happening so fast, it’s hard to see. Klinger falls to the ground and Lakutu crouches over his neck, as if sucking the life out of him, until Klinger is lying flat on the ground, dead. Lakutu comes to the front of the stage and smiles, exposing a cheap plastic set of costume vampire fangs. “Who depends on whom?” the artist statement reads, “Who is sucking the other dry?” (Monster Truck Reference Truck2016).

As with the Kurdi reenactment, this singular moment is dense with associations: Marx’s critique of vampirical capitalism (“dead labor which lives by sucking living labor” [1887:163]), the reanimism of the zombie, the zombieism of the mindless, repetitive production and consumption under late capitalism, Footnote 4 but also the Haitian vodou zombie as imagined resistance to chattel slavery; the disconcerting, insect-like, unhuman movements of the undead body; the image of the vampire as parasite; the vampire as a racial other, from Dracula to The Vampire Diaries; the vampire as site for cultural anxieties of miscegenation. I think of the language of parasitism used by far-right protestors against asylum seekers in Germany. It also strikes me that Klinger lying where Lakutu/Kurdi once lay is an act of surrogation, a substitution that reveals the impossibility of a substitution, revealing gaps and tears in the fabric of transatlantic culture (see, for example, Roach Reference Roach1996). The moment compacts capitalism, colonialism, and its discontents into a single gesture.

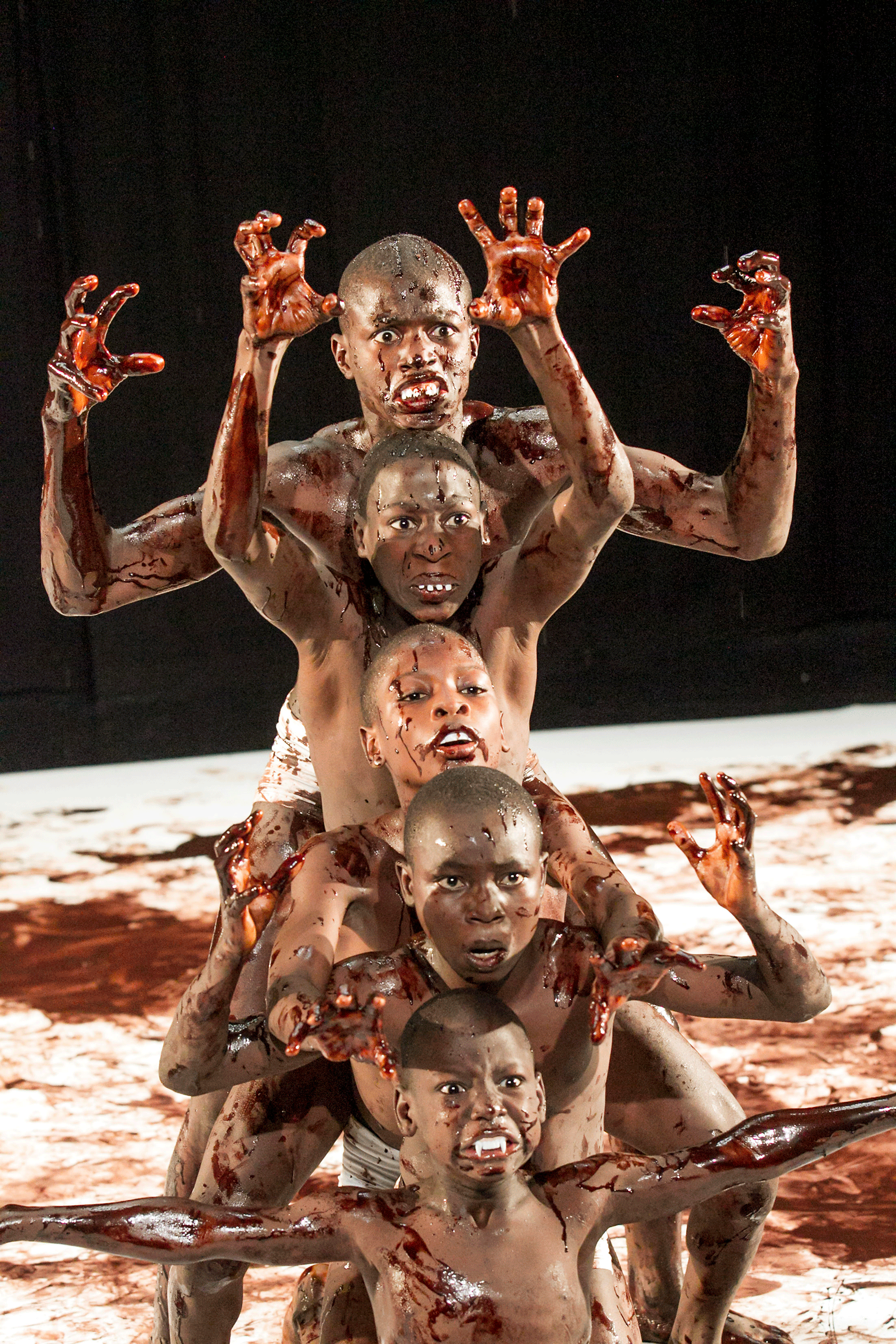

The parade of at once intensely familiar and inscrutable images continues. Klinger gets up and leaves. Four incrementally larger Black boys enter, wearing white briefs, and line up in height order next to John Lakutu, the smallest of the group. Klinger eats a banana. The five boys eat bananas, too. Chocolate sauce rains from the ceiling and the boys dance in it, lifting their faces to the ceiling to catch the syrup in their mouths, licking it off their hands. Their white briefs are soiled; it looks like shit. Their chocolate-covered bodies take on the high-gloss of US American minstrels. Their movements — coordinated, angular, energetic — are either Nigerian dance or a parody of Nigerian dance performed with a wink for audiences who don’t know the difference. Footnote 5 They somersault, they make a human pyramid, they line up one behind the other and wave their arms like showgirls. The boys are having fun, or they are not. They are being exploited, or they are not. Who is to know? Everyone is smiling. Tracy Chapman’s “Baby Can I Hold You” plays on repeat endlessly. “Sorry/is all that you can’t say/Years go by and still/Words don’t come easily/Like ‘Sorry, I’m sorry.’” The better part of an hour passes in choreography like this. “Years go by and still/Words don’t come easily/Like forgive me/Forgive me” (Chapman Reference Chapman1988).

Figure 6. Sorry by Monster Truck and Footprints of David/Segun Adefila. Ridwan Rasheed, John Lakutu, Moses Akintunde, Muiz Adebayo, and Waris Rasheed, dancing to “Baby Can I Hold You” by Tracy Chapman. Sophiensaele Berlin, 19 May 2016. (Photo courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

“Cliché, Appropriation, Presumptuousness”

German critics use the word “cliché” to describe Monster Truck’s métier. On the German theatre criticism website Nachtkritik, Michael Wolf describes the action of Sorry under the subheading: “Cliché, Appropriation, Presumptuousness” (2016). But even these terms seem too gentle. The “African dance”! The association of black bodies with culinary consumables! The chocolate rain! Footnote 6 The crass display of those starving African children we’ve heard so much about! The primitivizing and animalizing of these African performers eating bananas! These are crude, tired, and offensive images. Dorothea Marcus, in Theater heute, notes that Monster Truck “plays confidently on the keyboard of our inner stereotypes.” Her review of Sorry continues: “they are, although consciously displayed as jungle artifacts, terrific to watch” (Marcus Reference Marcus2017). Such images are tasteless. They are hurtful. They are not OK. Why, then, does Monster Truck keep putting them onstage?

For a generation of theatre-goers and scholars in the US, these questions may be too familiar, even dated. American playwrights like Suzan-Lori Parks and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins manipulate Jim Crow stereotypes in order to highlight ongoing white supremacy in the United States. Richard Pryor, Eddie Murphy, and Spike Lee have parodied these stereotypes in clubs and in major motion pictures. So too has this provocative dramaturgy been theorized since the 1990s. In “Return of the Repressed” (2002), Shawn-Marie Garrett compared Lee’s Bamboozled and plays by Parks to ongoing blackfacing by white actors. Rebecca Schneider, in The Explicit Body in Performance (1997), wrote about Spiderwoman Theatre: “they make explicit the ways their bodies have been staged, framed by colonial representational practices, and delimited. Here, they turn upon that historical representation of the native, upon colonial mimicry of native identity, with what might be called counter-mimicry” (1997:169).

Figure 7. Sorry by Monster Truck and Footprints of David/Segun Adefila, Ridwan Rasheed, John Lakutu, Moses Akintunde, Muiz Adebayo, and Waris Rasheed of Footprints of David, covered in chocolate, dancing to “Baby Can I Hold You” by Tracy Chapman. Sophiensaele Berlin, 19 May 2016. (Photo courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

But plays like those by Parks draw from a long and familiar repertoire of African American impersonation by white and black performers alike, as well as widespread public conversation in the US around blackness and culture more broadly. In a German performance context dominated by white artists, parodic displays of blackness have different connotations and social functions. After WWII, any conversation about racial difference was seen in Germany as a symptom of racism, and the continued absence of Germans of color on the stage reflects this basic principle of postwar racial thought. As David Theo Goldberg writes, “For Europeans, race is not, or really is no longer. [The erasure of race is a] desire at once frustrated and displaced, racist implications always lingering and diffuse, silenced but assumed, always already returning and haunting, buried but alive” (2006:334). In 2012, the so-called blackfacing debates erupted around a Berlin production of the naturalist drama I’m Not Rappaport, in which a white actor in blackface was cast as an African American on the grounds that no suitable black actor could be found for the role. In interviews, Schlosspark Theater artistic director Thomas Schendel painted himself as the victim of online trolling, stressing that previous productions of the play have used white actors in blackface without facing such backlash. “In Germany blackface is part of a theatre tradition that was never intended to be racist,” Schendel noted (in Ware Reference Ware2012). This is exactly the problem.

Katrin Sieg traces the history and politics of German blackfacing through another 2012 production in which black characters were played by white actors in blackface, Innocence: a major, state-funded, Michael Thalheimer–directed production of a new play by well-known playwright Dea Loher at the Deutsches Theater, in Berlin. Sieg notes that in Innocence, the black characters become white over the course of the production as their blackface makeup rubs off, foregrounding white guilt. Racial stereotype in Innocence, then, does not have a parodic but rather an assimilative function. Sieg summarizes, “Within the liberal terms set by the text, racial difference can only be expressed as primitive spectacle” (2015:139).

As bell hooks cautions, “If the many non-black people who produce images or critical narratives about blackness and black people do not interrogate their perspective, then they may simply recreate the imperial gaze — the look that seeks to dominate, subjugate, and colonize” (1992:7). In a theatre landscape where blackfacing by white actors was publicly defended in major media as recently as 2012 (e.g., Khuon Reference Khuon2012), beginning a more reflexive conversation about self-exploitation or counter-mimicry onstage is ambitious. Many spectators at Sorry — even at an independent venue like Sophiensaele — might believe that blackfacing is acceptable. Indeed, much of the work of scholars and activists in the blackfacing debates was intended to create discussion of this topic for the first time, encouraging white theatre-makers and audiences to “interrogate their perspectives” about images of blackness. Joy Kristin Kalu, for example, wrote essays explaining the history of US American minstrelsy, critiquing the lack of opportunities for German actors of color from conservatory training through to casting (2012, 2014).

In this context, is counter-mimicry possible? How can we calculate the cost of redeploying minstrel stereotypes when those stereotypes still circulate uninterrogated? Especially when, in the case of Sorry, those doing the self-exploitation are disempowered in Germany: underprivileged minors from Lagos, presumably unaware of the German “blackfacing debates” being held in dramaturgical roundtables, the Nachtkritik comment section, and academic fora. Like Innocence, Sorry presents a “primitive spectacle,” but unlike Innocence, Sorry refines, maximizes, and reflexively frames the spectacle as the dramaturgy of the piece. Monster Truck’s insistent pairing of exploitative clichés with metatheatrical critique in each of their performances — “we are exhibiting ourselves exhibiting them” — responds directly to German blackface productions and debates. The group flips hooks’s exhortation backwards: they recreate the imperial gaze in order to expose the ways in which other nonblack theatre-makers and audience members must interrogate their perspectives. It is certainly noteworthy that one of the few public arguments for the transformative critical potential of stereotype in performance came, remarkably, from a performance itself. Still, as many spectators asked at the panel discussions of the racial politics of Sorry, did the boys consent?

“Products but Also Wounds”

The Footprints dancers’ winking self-exotification in Sorry is further complicated by the work’s implicit references to Germany’s colonial relationship with Africa. While Germany has been celebrated for its Errinerungskultur (culture of remembrance), the nation’s early-20th-century involvement in present-day Namibia remains a blind spot. It was in Namibia that Germany executed its first genocide of the 20th century, the extermination of the Nama and Herero peoples from 1904 to 1908. This crime has been erased from German discourse (see Sieg Reference Sieg2015). As such, putting colonial stereotypes onstage produces a nascent public discourse about Germany’s colonial history and deep-seated antiblackness rather than simply re-producing long-standing existing discourse around blackness and performance as in the US American context.

Goldberg cautions that race in Europe is buried, but buried alive (2006:334). Images of animalized and primitivized Africans do not disappear when the history of colonialism is ignored in education, art, and politics. The images multiply. Swedish scholar-artist Temi Odumosu writes about colonial hangovers in advertising in Northern Europe:

Paradoxically, the silence around this past is foiled by the omnipresence of all these widely used and circulated images, which preserve in their historicism a palpable sense of colonial values (the black/brown body as commodity) and prejudices (the black/brown body as site of abuse). In this way they are products and also wounds, continuous reminders of unequal human relations. (2015)

Like the racist reproductions of a generically African girl still displayed on Swedish coffee packaging and napkins, Sorry is a “continuous reminder of unequal human relations” — this time, an intentional reproduction of colonial values, prejudices, and the racist images that accompany them. This intentionality gives the piece its power, but also its ability to inflict psychic harm on black Europeans, like Odumosu, who live with the consequences of these images (see Sharifi Reference Sharifi2018).

Watching Sorry, I thought of the schoolbooks, staged portraits, and ivory carvings sitting in gallery cases in the SAVVY Contemporary gallery across town. This motley collection comprises another artistic intervention into German colonial history — the Colonial Neighbors project. I wondered whether anyone was looking at those very pieces at the same moment I was at the performance. SAVVY stands “at the threshold of notions and constructs of the West and non-West, primarily to understand and negotiate between, and obviously to deconstruct the ideologies and connotations eminent to such constructs” (Ndikung Reference Ndikung2017); Colonial Neighbors is one of the gallery’s “pillar programs,” running for over five years. Jonas Tinius notes, “It is not just a passive reconstruction of historical objects and their epistemic contexts during German colonialism, but an ‘information space’ as the SAVVY project conveners describe it, that is aimed at examining ‘the post/colonial here and now’” (2018:143). The curators Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock, Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju, Cornelia Knoll, Marleen Schröder, and Jorinde Splettstösser have created an open-source archive of German colonial imagery: from cigarette packaging to family photo albums. Actual representations of the German colonial presence in Namibia mingle with — are inextricable from — piles of commercial racist kitsch. The curators stress the openness of this archive in their call for submissions. “The item can be a part of a family archive, a commercial product that catches your attention, a book that you find at a flea market, or a song that you hear” (SAVVY Contemporary n.d.).

Sorry and Colonial Neighbors share the same desire to make visible the “open wound” of the colonial and its afterlives. I saw Colonial Neighbors in its early days, when the project was beginning to outgrow a few stacked wood shipping crates of racist memorabilia. Excerpts from a family album of a German soldier living in a colony in Cameroon were projected on a blank wall opposite: animals, fruits, local people. SAVVY founder Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung was given the album by a relative, who was given it by a neighbor, who found it in his attic, the curators explained. This album provided the seed for the open archive, an archive that apparently already existed; someone just needed to collect it. In this sense, neither Colonial Neighbors nor Sorry is telling us something we don’t already know. These representations of Africa are Europe’s legacy, yet they remain in the present; they are coming out of the attic and into the art world.

The curators themselves call the archival objects Schrott — rubbish. It is hard to look at a package of “N — küsse” (N — kisses), the personified chocolate treats smiling with thick red lips. But we know what happens when we look away. “We see ourselves as working on an archive that is not ours, but an archive of those that contribute to it, or those who try to engage with colonial histories of oppression,” notes Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock (in Tinius Reference Tinius2018:130). This crowdsourcing not only plays into antielite curatorial strategies but also shifts the ownership of rubbish racism from the individual to the social: “These are commercial commodities that may not have caused concern for the people that used them” (131). The exhibit is not a passive display of objects but an active field in which German colonialism can be discussed, contested, and, though this seems unlikely in the logic of Sorry, repaired or apologized for.

In Berlin, 2016 was a big moment for bringing the German colonial era into the light. For the first time, the German Historical Museum devoted an exhibit to Germany’s colonial history. A group of activists called Berlin Postkolonial held their third “Street Renaming Festival” for Mohrenstrasse (Moor Street) Footnote 7 and led performative “city tours” explaining the presence of Togostrasse and Ugandastrasse to Berliners ignorant about the Berlin Conference, site of the 1844–45 so-called scramble for Africa: the divvying up of Africa into European colonies. Footnote 8 Activists and artists have helped make the legacy of the Berlin Conference more visible in Berlin. In early 2017, Coco Fusco created a performance at Sophiensaele in collaboration with KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Words May Not Be Found. The performance consisted simply of excerpts from “The Blue Book” read aloud: 47 sworn testimonies from survivors of the Nama and Herero genocide assembled to demonstrate Germany’s unfitness to control the colony and make a case for the transition of the colony from German to British control, after British South African forces defeated German occupying troops. The politics of these artistic and activist recovery projects are as clear as their aesthetics. They are an attempt to name and heal.

This kind of reparative process is not the project of Sorry. Monster Truck denies the political clarity of documentation and stages instead, as a spectacular grotesque, the ongoing unequal power relations between Europe and Africa.

In Sorry, the impossibility of apology, given the economic and geopolitical inequality between Nigeria and Germany, is exactly the point of the production. Into this situation, where fault, guilt, and redress seem inaccessible, steps Andreas Klinger, eating a banana while looking at five Nigerian boys lined up from smallest to tallest in their white boxer briefs, eyeing them like colonial objects on display. “Sorry/is all that you can’t say.”

Klinger, reentering now also in his underwear, begins a smashing, wailing drum solo: a futile paroxysm of white male dominance. After about 40 minutes of dancing to “Baby Can I Hold You,” the boys leave the stage and Lakutu is alone again, kneeling over puddles of chocolate and slurping them, licking his palms. And then it’s back to the opening scene. Lakutu lies face down on the stage, Klinger picks him up and cradles him in his arms, Lakutu awakes from the dead and sucks from Klinger’s neck until Klinger lies flat on the ground. Then: again. Lakutu lies next to Klinger, Klinger gets up, picks up Lakutu, a chocolatey Madonna and child. The staccato screeching of violins, the horror movie cliché, underscores Lakutu’s transformation into a vampire, Klinger falls to the ground and Lakutu crouches over his neck, focused, as if thirsty. Then: again. Again. Again. In his essay, “The Other Question,” Homi Bhabha argues that compulsive, “anxious” repetition combines with what is “always in place and already known,” to create the stereotype; this doubling in turn creates colonial discourse (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1983). It is as if Sorry’s choreography is taken straight from Bhabha’s playbook — repeating worn tropes ad nauseam in order to construct a theory of colonial discourse, one that allows Germany’s colonial relationship to Africa, that unspoken wound, to be made visible. So that Monster Truck can stick a finger right in it.

The Archive and the Art Market

Then the Footprints dancers come back, this time dressed up in white button-downs and black pants. Speaking Yoruba, they address the audience. Projected subtitles pose a critique of European desire for “exotic African art” that sounds decidedly like it was written by someone who went to Giessen: the boys compare European and African modernisms, praise Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, critique Leni Riefenstahl’s Nuba photographs, and name-drop Bruno Latour. I assume we are meant to acknowledge the irony. “Have you heard the band Vampire Weekend?” the subtitles begin. “They are a white, Ivy League band from the US with African influences. They even use African languages, something like Kwassa Kwassa” (Monster Truck Reference Truck2016). The boys laugh. The boys gesture broadly and repeat phrases, and the subtitles scroll: “Everybody seems enthusiastic about exotic African art these days. Is this mainly happening because people are looking for the last white spaces on the map? This is the new primitive art as a talisman for the moneyed class.” As I read the subtitles, I’m listening for the proper nouns: Latour, Vampire Weekend. But I don’t notice them, so I’m wondering: what are these performers really saying?

Figure 8. Andreas Klinger (right) as he dances “rescuing” John Lakutu in Sorry by Monster Truck and Footprints of David/Segun Adefila. Sophiensaele Berlin, 19 May 2016. (Photo by Florian Krauss; courtesy of Sahar Rahimi)

Then the punch line. Lakutu takes a microphone while the other four begin to cut into squares the white stage floor now smeared abstractly brown with chocolate. “We have some postmodern artworks for you. Guess how much they cost?” Lakutu asks the audience. “Five dollars?” “A million?” “Nothing?” John mumbles, “No” to each response from the audience. “It is postmodern African art,” he reminds the audience. “If you buy them, we use the money to pay my school fees, my school bag, school boots, toys, and bicycle. Please buy them. Thank you.” The subtitles flash: “Each painting 10 euro.” The other four dancers are inserting the cut stage into square frames and selling these framed pieces to the audience. The subtitles continue to flash: “Buy now!” “The show is over, but the sale goes on!”

These “gotcha” moments implicating the audience in a political critique posed by the performance are not uncommon in European Freie Szene theatre. What Monster Truck does differently is critique something we in the audience have already done: bought a ticket and sat through this production. Other political works in the independent scene may assume a kind of complicity between the audience and dominant cultural perspectives — such as, for example, andcompany&Co.’s 2013 Black Bismarck, which presupposes that the audience is unaware of the Berlin Conference and must be informed and chastised about the colonial history of German hero Otto von Bismarck. That is, Black Bismarck and many other performances render the presumed whiteness of the audience “critical” and therefore nonneutral (in the process constituting the normative theatre audience as white). Monster Truck is not invested so much in racializing whiteness as showing the mechanics of one instance of racialization — the commodification of “authentic” African art by Europeans — the very situation at hand.

Monster Truck in the Documentary Turn

Wolf’s Nachtkritik review of the performance praised John Lakutu’s imploring us to buy art to pay his school fees: “It’s not clear whether this is true or simply good marketing. Somehow or other, the cleverest moment of the evening” (Wolf Reference Wolf2016). The first commenter under the review rants, “Do you really think that John needs the money for his schooling, or that he uses this sentence as a marketing strategy? Did you not think for a moment that this might be a cliché being presented to you?” (Wolf Reference Wolf2016). Perhaps what makes Monster Truck controversial — and difficult to write about — is that this moment is clearly three things at once. I, like the commenter, find it hard to believe that one of the most public reviewers of Sorry could watch this plea for charitable donations at the end of such an evening and think it could be sorted into “truth” or “clever fiction” when the whole evening is an explicit, metatheatrical meditation on the twinning of authenticity and exploitation.

Even when Monster Truck names a problem explicitly (“This [the very performance you are currently attending] is the new primitive art as a talisman for the moneyed class”), it’s clear that they are also messing with us. My spiral of self-doubt writing this article — and critic Michael Wolf’s repeated acknowledgment of his own ignorance (“I could be wrong, because of course I have no idea about African dance”) — seems to be precisely calculated effects of the dramaturgy of the piece. When Sahar Rahimi, responding to my question, corrects me, saying that the subtitled text was written not by Monster Truck, but late Nigerian curator and critic Okwui Enwezor, famous champion of African contemporary art, I laugh aloud (Rahimi Reference Rahimi2019; see Bessing Reference Bessing2008). I fell for it, too.

It’s not necessarily wrong to say that Monster Truckers are significant members of a growing cadre of artists and curators bringing to light the colonial relationship between Germany and Africa. But such a statement misses their irony, their polyvalence, their blackest humor. Uniquely, Monster Truck creates a theatrical language for “all of the above” within a cultural rubric that strictly divides “true” from “false.” Lakutu’s plea may be true, and it may be good marketing, but it is certainly a self-aware cliché.

A small black child coming to the front of the stage to engage with the audience “as himself” might indeed be familiar to those who attend performances of the German independent scene. But within a dramaturgy of exaggeration, objectification, and stereotype, Lakutu’s request for money suggests multiple truths, which, in composite, suggest the impossibility of a single answer as to whether Lakutu “really” needs the money for his school fees. They suggest, moreover, the failure of the documentary mode.

It bears repeating the extent to which most independent scene German theatre depends upon, in some sense or another, an “irruption of the real” (Lehmann 2006:99). What may have originated with former Hebbel am Ufer (HAU) Intendant Matthias Lilienthal’s “hysterical longing for reality” (see for example Behrendt Reference Behrendt2004; see Balme Reference Balme2023) has become axiomatic across the independent scene, moving from the three HAU spaces to the Munich Kammerspiele and beyond. “No art shit! Only reality shit!” was and continues to be the independent scene’s credo (Emcke Reference Emcke2012:7). One of Lilienthal’s first hires at HAU was Rimini Protokoll (Helgard Haug, Stefan Kaegi, and Daniel Wetzel). Rimini Protokoll’s varied and dynamic performances take place over headphones and in buses, in stranger’s apartments and in virtual reality. All of Rimini Protokoll’s work has one thing in common: an interest in getting closer to the truth through performance. They write, “We do not believe in the authenticity of the first moment, the spontaneous appearance, but rather in the process of the theatre as one of authentication” (Haug and Wetzel Reference Haug and Wetzel2011:50). Ulrike Garde and Meg Mumford expanded this statement into a book-length project, Theatre of Real People, explaining how Rimini Protokoll uses “experts of the everyday” (Alltagsexperten) to create “authenticity effects” in performance (Mumford and Garde Reference Mumford and Garde2015:83). Footnote 9

This is where Monster Truck’s crass clichés, “amateurish” aesthetics, and layering of self-aware ironies make such an important intervention — dissociating the imperative toward authenticity from its political effects. Monster Truck demonstrates the limits of the real — the ontological gap between Schein and Sein, appearances and reality (Meierhenrich Reference Meierhenrich2012). In a review of Genghis Khan, Doris Meierhenrich writes,

Are [the actors with Down syndrome] allowed to “play” — can they? — or should they only “be themselves” and in this case give credence to that bugbear, the so-called real? That this reality is already at least as false as the human zoo re-enactment makes for a good parody. (2012)

Meierhenrich points straight at documentary theatre’s problem of combatting a culture of antitruth with newer, better, more theatrical truths: reality is already false.

So perhaps this turn toward reality cannot adequately explain what we see when we watch a white European mourning a dead African; nonactors or personal testimony cannot, really, unearth a buried history, or vivify the haunting specter of race in Germany. The colonial wound is vast: Hans-Thies Lehmann suggests that theatre’s only response might be “a politics of perception […] an aesthetics of responsibility (or response-ability)” (2006:185). In other words, we might begin to ask more searching questions about artists like Rimini Protokoll or their peers, such as Milo Rau and Hans-Werner Kroesinger. Can the documentary impulse reorient our politics of perception? Documentary dramaturgies centered around “the strange” demand a steady supply of strangers (following Mumford Reference Mumford2013:154). In a political landscape in which Germans of color are in a kind of existential double bind, seen as either German or Vietnamese (for example), a theatre reliant on authenticity effects recreates the idea that someone who is nonwhite must also be non-German. Such a theatre places reality somewhere “out there.” In a 2012 interview, Sieglinde Geisel and Barbara Villiger Heilig asked Matthias Lilienthal whether one needs to go to the theatre to find reality — isn’t it all around us already? “Not if, like me, you go through the city with blinders on,” Lilienthal replied. “Berlin discovered the Dong Xuan Center in the theatre!” (Geisel and Heilig 2012). The Dong Xuan Center is a Vietnamese wholesale market in Lichtenberg, an eastern exurb of Berlin. Did Lilienthal really assume that no Vietnamese German has entered HAU?

Monster Truck reproduces and explicitly parodies the “joy of discovery” (Entdeckerfreude; Mumford Reference Mumford2013:155) that forms the base of contemporary documentary theatre in the Freie Szene. Sorry, with its real-time reenactment of white Europeans’ hunger for African art within the piece, puts the act of discovery in scare quotes. Monster Truck shows the artificiality of these authenticating strategies by presenting patently inauthentic scenarios, like John Lakutu’s plea for money, that also have a kind of “probabilistic truth and predictability, in excess of what can be empirically proved” (Bhabha Reference Bhabha1983:18). Bhabha is writing here, as before, about the stereotype. By staging the representational process of dehumanizing black bodies, Monster Truck applies a unique strategy: shining a bright light into dark discourses, selling the audience’s own willing consumption of neocolonial power relationships back to them as art. Literally. Doing so, the ensemble members must risk reproducing these neocolonial power relations wholesale, as critiques that call their work racist suggest (see Sharifi Reference Sharifi2018). Perhaps Monster Truck is indeed not so much risking as inciting such responses.

Still, I argue that Monster Truck theatricalizes something like Sara Ahmed’s critique of the discovery discourse: “I suggest that we can only avoid stranger fetishism — that is, avoid welcoming or expelling the stranger as a figure which has linguistic and bodily integrity — by examining the social relationships that are concealed by this very fetishism” (2006:6). These are the social relationships that are staged in Sorry: uncomfortable, exoticizing, commodifying, parasitic, parodic, disturbingly racialized, and always and explicitly structured by power.

Refugees and the Burden of the Real

Despite a widespread, almost feverish interest in representing reality across the German independent scene — and in the state theatres that now hire these ensembles and directors — there seems to be little critical analysis of the effects of Lilienthal’s “hysterical longing for reality” on contemporary German theatre. A hunger for the authentic, especially when that “authentic” is in the form of racialized strangers assumed not to belong to the same community as the independent theatre scene audience, can reproduce colonialist or orientalist visual regimes alongside the democratic and egalitarian politics associated with documentary theatre.

The postmigrant theatre movement especially illustrates the dangers of longing for reality. Though postmigrant artists have made great strides to move Germans of color from “them” to “us,” they still mostly rely on the same authenticity imperative that structures the independent scene. For example, Schwarze Jungfrauen (Black Virgins) by Feridun Zaimoglu and Günter Senkel was a foundational performance for the postmigrant theatre movement, first directed by Neco Çelik at the 2006 Beyond Belonging Festival at HAU curated by Shermin Langhoff. The concerns of this festival — the experience of immigrants and especially their second-generation insider-outsider children — became the hallmark of Langhoff’s artistic directorships at Ballhaus Naunynstrasse and later the Maxim Gorki Theater. Schwarze Jungfrauen consists of fictionalized monologues from the perspective of “neo-Muslims” (Behrendt Reference Behrendt2006), religious Turkish women living in Germany; one such monologue concludes: “Everything is true. Almost everything is true.” Yet despite clear dramaturgical, directorial, and marketing decisions to leave the “truth value” of these monologues ambiguous, the work was largely received as documentary or “semidocumentary” theatre (Stewart Reference Stewart2014). Many postmigrant theatre-makers, like Zaimoglu, explicitly toe the line between testimony and fiction, yet are understood as representing a singular, authentic reality.

Yael Ronen, house director at the Gorki, also works in this ensemble-based, semifictionalized mode to stage experiences of communities not represented on other German stages. In one such performance, The Situation (2015), about Middle Easterners in Berlin, Ayham Majid Agha as Hamoudi deadpans to his roommate that he has contacts in ISIS. And then a broad smile spreads across his face. Kidding! He’s just a run-of-the-mill smuggler. In an interview, Agha sighed wearily: “There are a lot of people who ask me seriously if what I say on the stage is true, that I was Al Qaeda and then became a member of IS[IS].” (Agha Reference Agha2017). Indeed, the representational burden placed upon refugee actors working in Germany to play themselves, “to be real,” is immense.

And despite these theatre-makers insisting that they are artists first and refugees second (Agha Reference Agha2017), much “refugee theatre” in Germany does tend to rely on personal testimony in the form of border-crossing narratives. Almost every German production centering refugee artists also centers their “authentic” experiences: the Gorki’s Exil Ensemble’s 2017 collectively created Winterreise (Winter’s Journey); the now-disbanded Refugee Impulse Club’s Letters Home (2015); Anis Hamdoun’s The Trip (2016); the “Asylum Monologues” (2012) and “Asylum Dialogues” (2015) by the group Actors for Human Rights (see Sieg Reference Sieg2016).

On the one hand, such insistence on accuracy and authenticity in representing refugee or postmigrant perspectives onstage is a critical corrective to a theatre system with few opportunities for actors of color. Funding artists in exile to tell their own stories is a way to more ethically center the very real stories and experiences of migrants (Sieg Reference Sieg2016). But taken to its grimmest conclusion, these authenticity effects lead not to the kind of democratic inclusion documentary theatre-makers espouse, but to the use of refugees’ bodies as silent props, as in Nicolaus Stemann’s controversial production of Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Schutzbefohlenen (Charges), which premiered at the Thalia Theater in Hamburg (2014) (see Felber Reference Felber2016).

Richard Schechner writes in “Towards a Poetics of Performance” about performance art that foregrounds “actuality” and minimizes the theatrical frame:

People who want to make “everything real” […] are deceiving themselves if they think they are approaching a deeper or more essential reality. All of these actions — like the Roman gladiatorial games or Aztec human sacrifices — are as symbolic and make-believe as anything else onstage. What happens is that living beings are reified into symbolic agents. Such reification is monstrous, I condemn it without exception. ([1977] 1988:123)

And so Monster Truck follows the cultural logic of postracialism and colonial forgetting to its horrifying end-point: by ironically over-identifying with the concept of the authentic and selling it back to the audience. Using the tools of the theatre — metatheatricality, music, movement, and text — they create dense images that undercut themselves. They show how naive it is to think that a group of Europeans might sit in a dark room in a former trade union hall, watching a group of invited dancers from Nigeria, and experience a spectacle free from the history of German colonialism and the ongoing legacies of racial inequality. There is no authentic encounter, no healing, and there are no reparations to be had here. Monster Truck uses strategic, ironic doubling as a form of critique: they “show us exhibiting them” (Weigel Reference Weigel2012). Gerst, Rahimi, and Vera expose and exploit their partner performers to bring to light the ways in which other Freie Szene performances rely on the same logic of exposure and exploitation, only perhaps more politely. In their fun-house dramaturgy, Monster Truck reveals authenticity effects to be a distorting mirror. Thus, Monster Truck’s stereotypes in Sorry are perfectly accurate — not of Africans, but of Africa in the supposedly postracial, postenlightenment German imagination. Given the work’s antagonistic relationship toward “that bugbear, the so-called real” (Meierhenrich Reference Meierhenrich2012), I was surprised to see Sorry included in a 2019 documentary theatre festival. The festival’s title was “It’s the Real Thing.” And, in a sense, it is.