Psychopathic traits in adults refer to a constellation of pathological affective (e.g. lack of empathy), interpersonal (e.g. manipulation) and behavioral/lifestyle (e.g. risk taking, antisociality) personality traits (Hare & Neumann, Reference Hare and Neumann2008). These traits have consistently been associated with severe and stable patterns of aggressive and violent behaviors (Leistico, Salekin, DeCoster, & Rogers, Reference Leistico, Salekin, DeCoster and Rogers2008; Skeem, Polaschek, Patrick, & Lilienfeld, Reference Skeem, Polaschek, Patrick and Lilienfeld2011). Over the past decades, researchers have extended this construct to children under the assumption that psychopathic traits are relatively stable and could therefore be identified in the earlier stages of development (Frick, O'Brien, Wootton, & McBurnett, Reference Frick, O'Brien, Wootton and McBurnett1994; Lynam, Reference Lynam1996). Since then, evidence has shown that psychopathic traits in childhood can be conceptualized as three dimensions capturing the child's affective [callous-unemotional (CU)], interpersonal (narcissism-grandiosity), and behavioral patterns (impulsivity-irresponsibility) (Andershed, Kerr, Stattin, & Levander, Reference Andershed, Kerr, Stattin, Levander, Blaauw and Sheridan2002; Frick & Hare, Reference Frick and Hare2001). Extensive research on the CU dimension led to the inclusion of these traits as a specifier to the diagnosis of conduct disorder in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013].

With regards to their stability, however, results from community-based longitudinal studies suggest that psychopathic traits can be expected to change among some children. In fact, studies conducted on the CU dimension showed that these traits gradually increase in roughly 10% of children from the community, and gradually decrease in around 15% of them (Fanti, Colins, Andershed, & Sikki, Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017; Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory, & Viding, Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010; Klingzell et al., Reference Klingzell, Fanti, Colins, Frogner, Andershed and Andershed2016). These children represent an opportunity to study and better understand factors specifically associated with these unstable developmental trajectories during childhood. Ultimately, such knowledge is likely to enhance clinicians’ ability to prevent the exacerbation and stability at high levels of psychopathic traits within a developmental time frame in which traits are particularly malleable (Caspi & Shiner, Reference Caspi, Shiner, Rutter, Bishop, Pine, Scott, Stevenson and Taylor2008; Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, Reference Roberts, Walton and Viechtbauer2006).

Previous research suggests that a wide range of child- and family-level factors are associated with specific trajectories of psychopathic traits in childhood. At the child-level, children following a high-stable trajectory of CU or psychopathic traits show higher levels of temperamental fearlessness when compared to those following a low-stable trajectory (Byrd, Hawes, Loeber, & Pardini, Reference Byrd, Hawes, Loeber and Pardini2018; Klingzell et al., Reference Klingzell, Fanti, Colins, Frogner, Andershed and Andershed2016). These children also manifest higher levels of conduct problems and hyperactivity symptoms during middle (Byrd et al., Reference Byrd, Hawes, Loeber and Pardini2018; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017; Fontaine, Hanscombe, Berg, McCrory, & Viding, Reference Fontaine, Hanscombe, Berg, McCrory and Viding2018) and early childhood (Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010). Levels of these temperamental and behavioral features also differ between children following a low-stable trajectory and those following an increasing trajectory, with the latter presenting higher levels of temperamental and behavioral risks (Byrd et al., Reference Byrd, Hawes, Loeber and Pardini2018; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017; Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010, Reference Fontaine, Hanscombe, Berg, McCrory and Viding2018; Klingzell et al., Reference Klingzell, Fanti, Colins, Frogner, Andershed and Andershed2016). These results suggest that factors at the child-level are not only associated with the initial levels of psychopathic traits, but also with their exacerbation during childhood.

A similar trend is observed with family-level factors. Parents of children following a high-stable trajectory of CU or psychopathic traits tend to report lower socioeconomic status (Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Hanscombe, Berg, McCrory and Viding2018) as well as higher levels of parental distress (Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017), negative parental feelings (Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010), harsh or negative parenting (Byrd et al., Reference Byrd, Hawes, Loeber and Pardini2018; Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010, Reference Fontaine, Hanscombe, Berg, McCrory and Viding2018), and chaos in the home (Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010). The association between parenting characteristics and CU or psychopathic traits were also reported in a number of other studies in which CU/psychopathic traits were assessed cross-sectionally (e.g. Barker, Oliver, Viding, Salekin, & Maughan, Reference Barker, Oliver, Viding, Salekin and Maughan2011; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Wang, Shou, Lai, Zeng and Gao2020; Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Waller, Trentacosta, Shaw, Neiderhiser, Ganiban and Leve2016; Meehan, Maughan, Cecil, & Barker, Reference Meehan, Maughan, Cecil and Barker2017). In one of these studies, observations of adoptive mothers’ positive reinforcement toward their children at 18 months were negatively associated with the levels of CU traits at 27 months controlling for perinatal complications; however, the specific associations between perinatal complications and CU traits were not reported (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Waller, Trentacosta, Shaw, Neiderhiser, Ganiban and Leve2016). In another study, different associations were reported between specific types of parenting at age 4 years and CU traits at age 13 years for each sex: higher warm parenting was associated with lower CU traits in girls and higher harsh parenting was associated with higher CU traits in boys (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Oliver, Viding, Salekin and Maughan2011). In this latter study, a cumulative index of prenatal risks (e.g. financial difficulties, maternal psychopathology) was also positively associated with CU traits at age 13 among boys and girls, thus highlighting the importance of these very early-life factors in understanding the developmental roots of psychopathic traits in children.

The current study

This body of research has limitations. First, most studies focused on the CU dimension, which is viewed as a core feature of psychopathic traits in childhood (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, Reference Frick, Ray, Thornton and Kahn2014). However, increasing evidence supports the view that the broader construct of psychopathic traits (i.e. CU, narcissism-grandiosity and impulsivity-irresponsibility traits) could be a stronger predictor of antisocial outcomes in childhood compared to the consideration of only one dimension (Andershed et al., Reference Andershed, Colins, Salekin, Lordos, Kyranides and Fanti2018; Bégin, Déry, & Le Corff, Reference Bégin, Déry and Le Corff2020; Salekin, Reference Salekin2017). More so, a multidimensional conceptualization of psychopathic traits in childhood is closer to the original construct among adults (Hare & Neumann, Reference Hare and Neumann2008) and has been validated in childhood (e.g. Bégin, Déry, & Le Corff, Reference Bégin, Déry and Le Corff2019; Dong, Wu, & Waldman, Reference Dong, Wu and Waldman2014; Gorin et al., Reference Gorin, Kosson, Miller, Fontaine, Vitaro, Séguin and Tremblay2019). The investigation of the very early-life factors associated with developmental trajectories of the broader construct therefore has important empirical and clinical implications. Second, the factors associated with psychopathic traits were mostly assessed either concurrently to the assessment of these traits or at some point during childhood. There are very few studies on the associations between perinatal factors and later psychopathic traits and, to our knowledge, none of them focused on a broad range of perinatal/early-life factors and trajectories of psychopathic traits in childhood. Hence, knowledge is lacking on the very early-life factors, assessed within the first months/years of life, that are associated with specific trajectories of psychopathic traits during childhood. Yet, factors occurring within this developmental period have been linked to later difficulties such as externalizing (e.g. conduct problems) and internalizing (e.g. suicide attempts) mental health problems (Mathewson et al., Reference Mathewson, Chow, Dobson, Pope, Schmidt and Van Lieshout2017; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Maughan, Menezes, Hickman, MacLeod, Matijasevich and Barros2015; Orri et al., Reference Orri, Russell, Mars, Turecki, Gunnell, Heron and Geoffroy2020b). This period has been shown to be important for understanding the origins of psychopathology across the life course (Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, Reference Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen2009) and for prevention efforts (Brennan & Shaw, Reference Brennan, Shaw, Krohn and Lane2015). Thus, identifying perinatal and early-life factors associated with developmental patterns of psychopathic traits is critical to enhance our ability to detect and prevent these traits as early as possible. The current study therefore aimed to address this gap by identifying perinatal and early-life factors associated with specific developmental trajectories of psychopathic traits during childhood. As a previous study reported sex differences in these associations (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Oliver, Viding, Salekin and Maughan2011), sex interactions were also explored.

Method

Participants and procedures

The Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD) is a representative sample of 2120 youths born in the province of Quebec (Canada) in 1997 and 1998 (Orri et al., Reference Orri, Boivin, Chen, Ahun, Geoffroy, Ouellet-Morin and Côté2020a). Participants were recruited through a stratified procedure accounting for the area of living and birth rate using the Quebec Birth Registry. Children were aged 5 months old at the first assessment and were assessed annually or biennially until they were aged 21 years old (study still ongoing). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for each assessment to which they agreed to participate. The study protocol was approved by the Quebec Institute of Statistics and the Sainte-Justine Hospital Research Centre ethics committees.

Data used in the current study were collected from the pregnancy and childbirth medical records and from mothers when children were aged 5 months, 1.5 years, and 2.5 years (perinatal and early-life factors), as well as from teachers when children were aged 6, 7, 8, 10, and 12 years (psychopathic traits). Due to longitudinal attrition and varying participation rates at the different assessment time points, 1631 children had available data on childhood psychopathic traits and were retained for the analyses of the current study (76.93% of the initial QLSCD sample). Comparing children with and without psychopathic traits data revealed significant differences in the proportion of girls [40.90% in the excluded children v. 51.50% in the included children, χ2(1) = 16.92, p < 0.001, Cramer's V = 0.09 (small effect size)]. Differences between children included and excluded from the current study are presented in the online Supplementary Table S1.

Measures

With the exception of the psychopathic traits scale, all scales used in the current study were those originally created by the QLSCD investigators. These scales are briefly described below. Following recommendations by Gaderman, Guhn, and Zumbo (Reference Gaderman, Guhn and Zumbo2012), ordinal αs are provided throughout the article for scales using items with 2–7 response options, and Cronbach's αs are provided for scales using items with more than seven response options.

Psychopathic traits

Psychopathic traits were assessed using 10 teacher-rated items answered on a three-point ordinal scale (0 = never or not true, 1 = sometimes or somewhat true, 2 = often or very true). These items were selected from the teacher-rated questionnaires of the QLSCD because of their concordance with items from the Antisocial Process Screening Device, a well-validated measure of psychopathic traits designed for children aged 6–13 years old (Frick & Hare, Reference Frick and Hare2001). Three items captured the CU dimension (e.g. ‘Was unconcerned about the feelings of others’), four captured the narcissism-grandiosity dimension (e.g. ‘Used or conned others’), and three captured the impulsivity-irresponsibility dimension (e.g. ‘Engaged in risky or dangerous activities’). The 10 items are provided in the online Supplementary Table S2. The internal consistency of the scale was satisfying, with αs ranging from 0.93 to 0.95 across assessment ages. Confirmatory factor analyses supported the unidimensional structure of the scale across assessment ages (online Supplementary Table S3), as well as its structural and metric invariance, both longitudinally and across sexes (online Supplementary Table S4). The scale also showed the expected pattern of associations with external criterion variables, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally (online Supplementary Tables S5–S6).

Perinatal factors

A total of 24 perinatal factors were aggregated into five composite variables (fetal growth adversities, pregnancy complications, birth/delivery adversities, psychotropic exposures during pregnancy, and socioeconomic adversities), and into a total cumulative index (see online Supplementary Table S7 for the operationalization of all perinatal factors).

Child-level early-life factors

Difficult temperament

Difficult temperament was assessed by mothers at age 1.5 years using seven items from the fussy-difficult scale of the Infant Characteristics Questionnaire (Bates, Freeland, & Lounsbury, Reference Bates, Freeland and Lounsbury1979; e.g. ‘How easily does he/she get upset?’). Each item was scored on a seven-point ordinal scale. The scale showed satisfying internal consistency (α = 0.84).

Hyperactivity, physical aggression, and opposition

The three variables were assessed by mothers at age 1.5 years. Hyperactivity was assessed by seven items (e.g. ‘Can't sit still, is restless or hyperactive’), physical aggression was assessed by nine items (e.g. ‘Physically attacks others’), and opposition was assessed by five items (e.g. ‘Had temper tantrums or hot temper’). All items were answered on a three-point ordinal scale ranging from 0 (never or not true) to 2 (often or very true). Items of the hyperactivity and physical aggression scales of the QLSCD protocols were drawn from the Ontario Child Health Survey (Offord, Boyle, Fleming, Blum, & Grant, Reference Offord, Boyle, Fleming, Blum and Grant1989) and from the Montreal Longitudinal and Experimental Study (Tremblay, Vitaro, Nagin, Pagani, & Séguin, Reference Tremblay, Vitaro, Nagin, Pagani, Séguin, Thornberry and Krohn2006). Items of the opposition scale of the QLSCD protocols were drawn from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001). The internal consistencies of the scales were satisfying, with αs of 0.81 (hyperactivity), 0.91 (physical aggression), and 0.72 (opposition).

Family-level early-life factors

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status was assessed using a composite measure based on the education levels of the two parents, the prestige levels of their occupations, and the total household income when children were aged 5 months. The method used to create the composite measure is further described in Willms and Shields (Reference Willms and Shields1996) and in the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) online documentation: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=4630.

Marital support

Mothers’ perception of the support provided by their partner was assessed when the children were aged 5 months using five items (e.g. ‘To what extent do you feel supported by your current spouse in the baby caretaking?’) answered on an 11-point continuous Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (totally). The scale showed satisfying internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.88).

Maternal efficacy

Mothers’ perception of self-efficacy in their parental role was assessed when the children were aged 5 months using four items (e.g. ‘I feel that I am very good at calming my child down when he/she is upset, fussy or crying’) based on the Maternal Self-Efficacy Scale (Teti & Gelfand, Reference Teti and Gelfand1991) and answered on an 11-point continuous Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all what I think) to 10 (exactly what I think). Internal consistency of the scale was satisfying (α = 0.74).

Maternal impact

Mothers’ perception of having an impact on their child's behaviors and development was assessed using five items (e.g. ‘My behavior has little effect on the development of emotions in my child’ reverse scored) reported by the mothers when their child was aged 5 months. The five items were answered on an 11-point continuous Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all what I think) to 10 (exactly what I think). The scale showed satisfying internal consistency (α = 0.73).

Mother's depressive symptoms

Mother's depressive symptoms during the past week were assessed by seven (5 months assessment; postpartum period) and six (1.5 years assessment) items (e.g. ‘I felt that everything I did was an effort’) answered on a four-point ordinal scale ranging from 1 (rarely or none of the time – less than one day) to 4 (most or all of the time – 5–7 days). The items were selected from the National Institute of Mental Health Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977), a commonly used self-report measure of depressive symptoms. The αs of the scale were of 0.88 at the two assessment ages.

Positive, hostile, and consistent parenting

The three types of parental practices were assessed by mothers’ reports at age 2.5 years using items from the NLSCY based on an adaptation of the Parent Practices Scale (Strayhorn & Weidman, Reference Strayhorn and Weidman1988). The positive parenting scale contains six items (e.g. ‘How often did you do something special with him/her that he/she enjoys?’), the hostile parenting scale contains eight items (e.g. ‘How often did you use physical punishment?’), and the consistent parenting scale contains seven items (e.g. ‘When you gave him/her a command or order to do something, what portion of the time did you make sure he/she did it?’). All items were answered on a five-point ordinal scale. The αs of the scales were acceptable (positive α = 0.68, hostile α = 0.74, consistent α = 0.66).

Data analysis

For all child- and family-level early-life factors with the exception of socioeconomic status, items scores were averaged, and total scores were converted on a 0–10 scale. Analyses were conducted using Mplus 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998) and IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corp, 2019). Developmental trajectories of psychopathic traits were identified with latent class growth analyses (LCGA) using all available psychopathic traits data (ages 6, 7, 8, 10, and 12 years). As the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) was higher in the quadratic v. linear a priori model, linear models were retained in subsequent analyses. Variances of the two growth parameters of the linear model (intercept and slope) were significant at the p < 0.001 level, which suggested significant heterogeneity in developmental trajectories of psychopathic traits in this sample and justified investigation of latent trajectory classes.

Models of LCGA with 2–5 classes were conducted and compared based on conventional indices used to assess model fit in LCGA: a lower BIC value indicates better fit, a non-significant Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood test (LMR-LRT) indicates better fit of a model with k–1 class, and entropy value ⩾0.70 suggests clear classification across classes (Nagin & Tremblay, Reference Nagin and Tremblay2005; Wang & Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2012). Parsimony as well as theoretical and clinical relevance were also considered in selecting the best-fitting model. Once the retained model was identified, groups were formed by assigning children to their most likely class membership.

The associations between perinatal/early-life factors and trajectories of psychopathic traits were examined using multinomial logistic regression models controlling for child sex. Interaction terms between child sex and perinatal/early-life factors were entered in a second set of analyses to explore moderation by child sex. All variables were standardized prior to analyses and positively worded scales were reversed (i.e. higher scores indicating higher levels of impairment for all variables). Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1 and frequencies of all perinatal factors are presented in online Supplementary Table S8.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of perinatal and early-life factors in total sample and across trajectory groups

Note. Descriptive statistics are reported using scales’ raw scores (unstandardized and unreversed). s.d., standard deviation; y., years; m., months.

Results

Developmental trajectories of psychopathic traits across childhood

Figure 1 depicts the retained LCGA model of psychopathic traits trajectories across childhood and shows fit indices of all tested models. The four-trajectory model was selected based on the previously mentioned conventional fit indices. This model also showed excellent consistency with results from previous longitudinal studies conducted on CU traits in similar community-based samples (e.g. Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017; Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010). Psychopathic traits trajectories were as follows: High-stable (4.48% of the sample, 17.81% girls, intercept = 2.17, p < 0.001, slope = 0.06, p = 0.339), Increasing (8.77% of the sample, 34.27% girls, intercept = 0.01, p = 0.941, slope = 0.29, p < 0.001), Decreasing (11.47% of the sample, 34.22% girls, intercept = 1.58, p < 0.001, slope = −0.22, p < 0.001), Low-stable (75.29% of the sample, 58.14% girls, intercept = −0.37, p < 0.001, slope = −0.01, p = 0.300). The proportions of girls were significantly different from one trajectory class to another, χ2(3) = 94.22, p < 0.001, with a moderate to large effect size (Cramer's V = 0.24), which justified the inclusion of sex as a covariate in all regression models.

Fig. 1. Developmental trajectories of psychopathic traits across childhood. Note. Fit indices of the two-trajectory model: Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) = 13946.01, Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood test (LMR-LRT): p < 0.000, entropy = 0.90. Fit indices of the three-trajectory model: BIC = 13690.72, LMR-LRT: p = 0.119, entropy = 0.85. Fit indices of the four-trajectory model: BIC = 13390.62, LMR-LRT: p = 0.013, entropy = 0.87. Fit indices of the five-trajectory model: BIC = 13285.59, LMR-LRT: p = 0.575, entropy = 0.85.

Associations between perinatal/early-life factors and trajectories of psychopathic traits

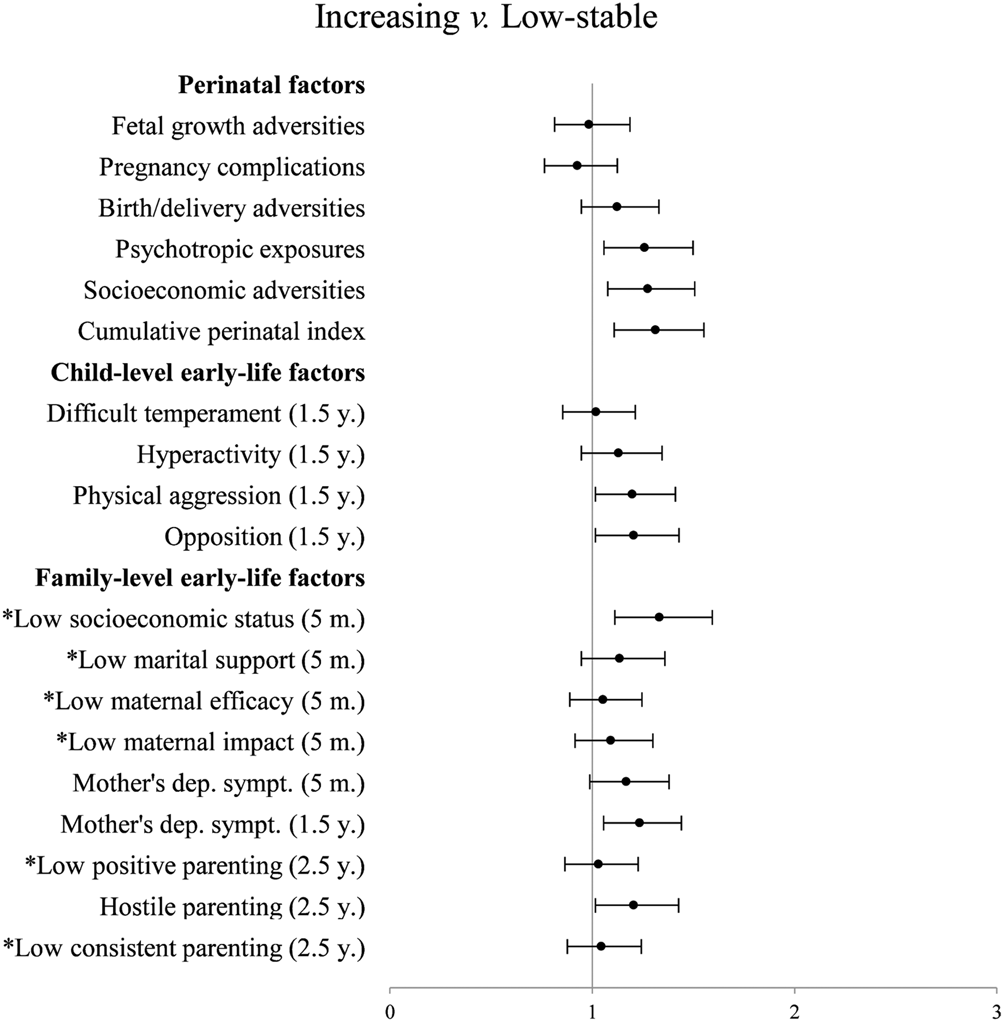

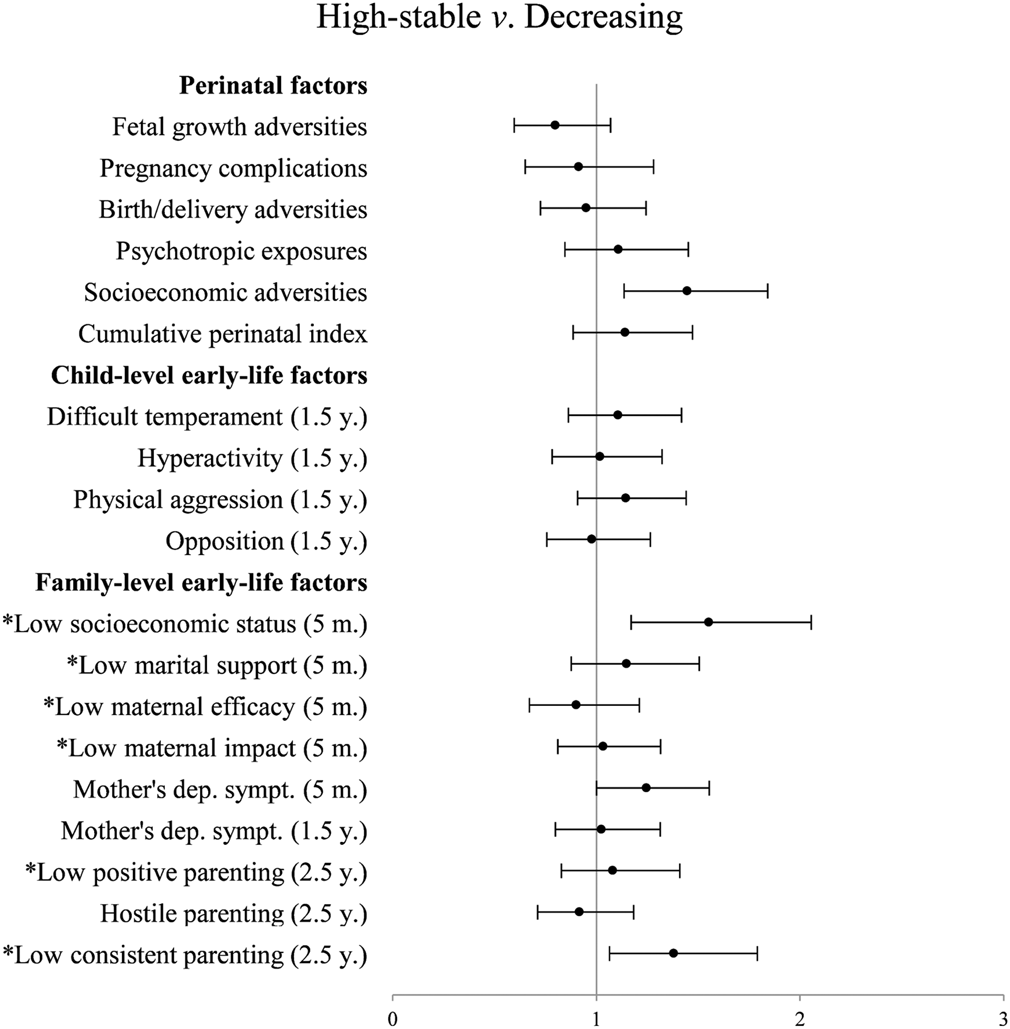

Results of the three main contrasts of interest from the regression models (i.e. High-stable v. Low-stable, Increasing v. Low-stable, and High-stable v. Decreasing) are depicted in Figs 2–4 (results of the three additional contrasts are presented in the online Supplementary Figs S9–S11). Three main findings emerged from these results.

Fig. 2. Perinatal and early-life factors associated with membership to the High-stable trajectory v. the Low-stable trajectory of psychopathic traits. Note. Dependent variable: membership to the High-stable v. the Low-stable trajectory as the reference group. Scales of variables identified with an asterisk were reversed for interpretation purposes: higher scores indicate greater levels of impairment for all variables. All variables are z standardized. Odds ratios are adjusted for child sex. y., years; m., months.

Fig. 3. Perinatal and early-life factors associated with membership to the Increasing trajectory v. the Low-stable trajectory of psychopathic traits. Note. Dependent variable: membership to the Increasing v. the Low-stable trajectory as the reference group. Scales of variables identified with an asterisk were reversed for interpretation purposes: higher scores indicate greater levels of impairment for all variables. All variables are z standardized. Odds ratios are adjusted for child sex. y., years; m., months.

Fig. 4. Perinatal and early-life factors associated with membership to the High-stable trajectory v. the Decreasing trajectory of psychopathic traits. Note. Dependent variable: membership to the High-stable v. the Decreasing trajectory as the reference group. Scales of variables identified with an asterisk were reversed for interpretation purposes: higher scores indicate greater levels of impairment for all variables. All variables are z standardized. Odds ratios are adjusted for child sex. y., years; m., months.

First, only a few perinatal factors but several early-life factors were associated with membership to the High-stable v. the Low-stable trajectory of psychopathic traits in childhood. For perinatal variables, higher levels of socioeconomic adversities and higher scores on the cumulative index increased the odds of following the High-stable trajectory. Additional fine-grain analyses of individual perinatal factors (online Supplementary Table S12) revealed that five out of 24 factors were associated with the High-stable v. the Low-stable trajectory: four referring to early socioeconomic adversities (low maternal education, low paternal education, non-intact family, and low maternal age at childbirth) and one referring to psychotropic exposures during pregnancy (maternal smoking). Regarding early-life factors, higher scores on all child-level factors (difficult temperament, hyperactivity, physical aggression, and opposition, all assessed at age 1.5 years) were associated with a higher probability of following the High-stable v. the Low-stable trajectory. Several family-level early-life factors were also associated with membership to this trajectory of psychopathic traits. Lower socioeconomic status, lower maternal impact, and higher levels of mothers’ depressive symptoms at age 5 months, as well as lower levels of positive and consistent parenting at age 2.5 years were associated with a higher probability of following the High-stable trajectory.

Second, the perinatal and early-life factors that were associated with the Increasing v. the Low-stable trajectory were different than those associated with the High-stable v. the Decreasing trajectory. Regarding perinatal factors, for example, while higher levels of psychotropic exposures during pregnancy, socioeconomic adversities, and the cumulative perinatal index were associated with the Increasing v. the Low-stable trajectory, only socioeconomic adversities were associated with the High-stable v. the Decreasing trajectory. At the child level, higher levels of physical aggression and opposition at age 1.5 years were associated with a higher probability of following the Increasing v. the Low-stable trajectory, but all child-level factors were unrelated to the odds of following the High-stable v. the Decreasing trajectory. At the family level, higher levels of mothers’ depressive symptoms at age 1.5 years and hostile parenting at age 2.5 years were associated with a higher probability of following the Increasing v. the Low-stable trajectory, while higher levels of earlier mothers’ depressive symptoms (at child age 5 months) as well as lower levels of consistent parenting at age 2.5 years were associated with increased odds of following the High-stable v. the Decreasing trajectory. Of note, socioeconomic status was associated with the three contrasts of interest, and levels of marital support and maternal efficacy at child age 5 months were not related to any of them.

Third, only a few associations were significantly moderated by child sex. Five significant interaction terms were identified among the main contrasts of interest. Simple slope analyses revealed that high birth order was associated with a higher probability of following the High-stable v. the Low-stable trajectory among girls only (girls: b = 1.82, s.e. = 0.68, p = 0.008; boys: b = −0.31, s.e. = 0.75, p = 0.683). Likewise, delivery acceleration usage at childbirth (girls: b = 0.91, s.e. = 0.34, p = 0.007; boys: b = −0.04, s.e. = 0.23, p = 0.849), low maternal education (girls: b = 1.50, s.e. = 0.31, p < 0.001; boys: b = 0.09, s.e. = 0.32, p = 0.781), and lower levels of socioeconomic status (girls: b = 0.63, s.e. = 0.15, p < 0.001; boys: b = 0.07, s.e. = 0.13, p = 0.606) were associated with an increase in the odds of following the Increasing v. the Low-stable trajectory among girls but not boys. Finally, high birth order was also associated with membership to the High-stable v. the Decreasing trajectory in girls only (girls: b = 2.23, s.e. = 0.97, p = 0.022; boys: b = −0.40, s.e. = 0.83, p = 0.633).

Discussion

Consistent with prior studies showing that all three dimensions of psychopathic traits tend to follow analogous developmental trajectories during childhood (Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017; Klingzell et al., Reference Klingzell, Fanti, Colins, Frogner, Andershed and Andershed2016), our results showed that the broader construct of these traits follows very similar developmental trajectories to those observed for the CU dimension in community-based samples. In addition, the proportions of boys and girls following each trajectory were comparable to those reported for trajectories of CU traits more specifically (e.g. Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010). These trajectories allowed us to identify perinatal/early-life factors associated with specific developmental pathways of psychopathic traits in childhood (e.g. with their exacerbation or stability at high levels).

This study revealed that a few perinatal but several child- and family-level early-life factors assessed very early in the child's life are already related, although with small effect sizes, to their psychopathic traits’ developmental trajectory between 6 and 12 years later. Consistent with prior studies conducted either specifically on CU traits (e.g. Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017; Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Hanscombe, Berg, McCrory and Viding2018) or on broader conceptualizations of psychopathic traits (Byrd et al., Reference Byrd, Hawes, Loeber and Pardini2018), many factors at the child- (temperamental and behavioral features) and family-level (mothers’ depressive symptoms, parenting) were associated with specific developmental trajectories of these traits during childhood. Global perinatal adversity was also associated with trajectories of the broader construct of psychopathic traits in this study, which is also consistent with the previous study that had reported significant associations between prenatal risks and CU traits in early adolescence (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Oliver, Viding, Salekin and Maughan2011). Our results extend previous findings by assessing all child- and family-level risk factors very early in children's development, as well as by revealing that the specific perinatal factors that appear to be most important for later development of psychopathic traits are those referring to early socioeconomic adversity and to psychotropic exposures during pregnancy. Although the analytical approach does not allow causal inferences, these factors can be interpreted as the early signs of a long-lasting developmental sequence taking root very early in the child's life. These results therefore highlight the relevance of early prevention efforts aimed at reducing the risks for the development or maintenance of elevated levels of psychopathic traits during childhood.

Further, our results showed that the early-life factors associated with the exacerbation of psychopathic traits (instead of low and stable levels) are different from those associated with their stability at high levels. For example, factors at the child level (physical aggression and opposition at age 1.5 years) were associated with increasing levels of psychopathic traits. These results are consistent with those of previous longitudinal studies on CU traits (e.g. Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010) and could be indicative of what has been referred to as a complication/scar association between personality and antisocial behavior, according to which engagement in antisocial behavior is posited to contribute to changes in personality traits (Morizot, Reference Morizot, Morizot and Kazemian2015). Inversely, child-level factors did not appear to be associated with the stability at high levels (v. attenuation) of psychopathic traits. Instead, mothers’ higher levels of depressive symptoms, as well as lower levels of early consistent parenting, were related to stable-high levels of psychopathic traits. These results are consistent with previous studies conducted on the importance of early parenting (e.g. Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Waller, Trentacosta, Shaw, Neiderhiser, Ganiban and Leve2016; Waller, Gardner, & Hyde, Reference Waller, Gardner and Hyde2013). They suggest that, while early child-level factors do not allow to distinguish those most at-risk of showing stable psychopathic traits among those with ‘initially’ high levels of these traits in childhood, parents can still reduce their risk of stability by adopting consistent parental practices as early as the toddlerhood period.

Our results also tend to show that the very early-life factors associated with different trajectories of psychopathic traits during childhood are similar among boys and girls. However, it is worth noting that all sex interaction effects observed in the three main contrasts of this study revealed greater risks for girls. Also, the fact that most factors that significantly interacted with child sex were related to children's environment is consistent with results from a previous study highlighting the role of environmental factors on girls’ CU traits (Fontaine et al., Reference Fontaine, Rijsdijk, McCrory and Viding2010). Potential sex differences should be further investigated with research aimed at clarifying early developmental pathways to psychopathic traits in children. In addition, as our results revealed significant associations between broader psychopathic traits and several early-life factors that had also been linked to CU traits, future research should investigate to what extent these two conceptualizations share the same early risk factors.

Strengths, limitations, and clinical implications

This study has important strengths such as its multi-informant and longitudinal design covering a 12-year time span and the use of official medical records for the assessment of most perinatal factors. Limitations must also be acknowledged. First, the non-significant interaction terms between most perinatal/early-life factors and sex could be partially explained by the relatively low number of girls in the High-stable and Increasing trajectories. Second, the internal consistencies of the positive and consistent parenting scales were lower and could have inflated the risk of a type II error. Third, a relatively large number of regression models were conducted, which could have inflated the risk of a type I error. However, we purposely did not apply a correction for multiple comparisons given the exploratory nature of our study and our aim to guide future research toward promising very early-life factors involved in developmental pathways of psychopathic traits.

Although most significant associations were of small effect sizes, which could be explained by the long time lapse between the assessments of early-life risk factors and psychopathic traits as well as by the relatively high amenability to change during the early childhood period, we found that the presence of early-life risk factors increased the probability of presenting psychopathic traits in childhood. These results reinforce the importance of early prevention efforts (e.g. parenting-focused interventions) aimed at preventing the stability at high levels or the exacerbation of psychopathic traits across childhood (Waller et al., Reference Waller, Gardner and Hyde2013). Early interventions targeting both child- (early temperamental and behavioral problems) and family-level components (mothers’ depressive symptoms and parenting characteristics) as early as the child's first months of life could reduce the risk of developing or maintaining childhood psychopathic tendencies. Interventions during pregnancy and early childhood, which provide support to parenting behavior and to parental mental health, could significantly prevent the development of children's psychopathic traits (Tremblay, Vitaro, & Côté, Reference Tremblay, Vitaro and Côté2018). For instance, promoting consistent parental practices for children with high initial levels of psychopathic traits could maximize their likelihood of attenuation and hence substantially reduce chronic behavior problems. Providing support to mothers with depressive symptomatology also appears particularly important (Olds et al., Reference Olds, Kitzman, Anson, Smith, Knudtson, Miller and Conti2019; Tremblay et al., Reference Tremblay, Vitaro and Côté2018).

Funding

This work, as part of the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD), was supported by the Québec Government's Ministry of Health and Ministry of Family Affaires, the Lucie and André Chagnon Foundation, the Quebec Research Funds – Society & Culture, the Quebec Research Funds – Health, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Vincent Bégin received a postdoctoral fellowship from the Quebec Research Funds – Society & Culture.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures that contributed to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001586