The majority of structural neuroimaging studies in schizophrenia have found progressive changes such as grey matter loss in subcortical regions. Reference DeLisi1 There has been considerable controversy about what causes the progressive changes. Possible explanations include the effects of medication, Reference McClure, Phillips, Jazayerli, Barnett, Coppola and Weinberger2 reduced neuropil Reference Selemon and Goldman-Rakic3 and excitotoxicity induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor dysfunction. Reference Olney and Farber4 One of the proposed methods to investigate the relative contribution of these factors is to combine volumetric analyses with functional and neurochemical studies. Reference DeLisi1 Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) at high field strengths allows examination of some aspects of excitotoxic processes by the quantification of both glutamate and its precursor glutamine in a small volume of interest. Very few studies have correlated longitudinal volumetric and neurochemical measurements in schizophrenia.

We previously reported elevated glutamine levels in the left anterior cingulate and left thalamus in never-treated first-episode schizophrenia Reference Théberge, Bartha, Drost, Menon, Malla and Takhar5 and decreased levels of glutamate and glutamine in the left anterior cingulate of chronically ill patients, Reference Théberge, Al-Semaan, Williamson, Menon, Neufeld and Schaefer6,Reference Tayoshi, Sumitani, Taniguchi, Shibuya-Tayoshi, Numata and Iga7 which supports the possibility of an excitotoxic process. However, these illness phase-related changes may be confounded by age and medication effects. More recently, our group examined longitudinal changes in glutamatergic metabolites and grey matter in first-episode schizophrenia over 30 months. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 Within the patient group, decreased thalamic glutamine was found at 30 months compared with baseline. Furthermore, a striking loss of grey matter in widespread cortical regions such as dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and temporal regions was found over 30 months in these patients. Grey matter loss in the superior temporal gyrus was significantly correlated with the loss of thalamic glutamine. The correlation between grey matter and glutamine loss could indicate a degenerative process but the study was limited by a relatively short follow-up period. If there is a degenerative process in schizophrenia, it likely persists for several years.

The purpose of this study was to extend our glutamatergic and volumetric assessments to 7 years in patients with first-episode schizophrenia studied before treatment and after stabilisation with antipsychotics. We hypothesised that if there is a degenerative process in these individuals, we would see a loss in not only glutamine but also glutamate and N-acetylaspartate (NAA), a marker of neuronal integrity Reference Clark9 in the anterior cingulate and the thalamus. The glutamate–glutamine cycle accounts for 80–100% of total glutamate trafficking in the brain. Reference Rothman, Behar, Hyder and Shulman10 Thus glutamine may be an indicator of glutamatergic signalling, Reference Rowland, Bustillo, Mullins, Jung, Lenroot and Landgraf11 while loss of glutamate, glutamine and NAA may suggest loss of synaptic neuropil. We further hypothesised that the changes in these metabolites would correlate with loss of grey matter, particularly in regions which might be expected to be involved in schizophrenia such as the frontal and the temporal regions. If these changes in glutamatergic metabolites reflect meaningful functional brain changes, we hypothesised that we would see a correlation between changes in these metabolites and measurements of social functioning despite treatment with medication.

Method

Participants

Seventeen patients diagnosed with schizophrenia participated in this study (schizophrenia group). The diagnosis was established with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams12 by a psychiatrist (P.C.W.). Ten of the patients were classified as having paranoid type schizophrenia and seven patients were classified as having an undifferentiated subtype. Patients were scanned three times: at their first assessment in a never-treated state, at 10 months and at 80 months after their initial examination. The MRS data for the never-treated state and at 10 months from 14 patients with schizophrenia have been reported in our previous study. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 Demographic information on participants is shown inTable 1. Education levels, handedness and length of illness were rated as in our previous study. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 Symptoms were evaluated with the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) Reference Andreasen13 and the Scale for the Assessment of the Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Reference Andreasen14 Social functioning was evaluated with the Life Skills Profile Rating Scale (LSPRS), Reference Rosen, Hadzi-Pavlovic and Parker15 composed of 39 items with a four-point response scale. This questionnaire was completed either by a family member living with the patient or by a caseworker via telephone interview within a few weeks after the patient's latest assessment.

Table 1 Participants’ demographic information and data availability

| Schizophrenia group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT (n = 17) | 10 months (n = 17) | 80 months (n = 17) | Con1 (n = 17) | Con2 (n = 17) | |

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 25 (7) | 25 (8) | 32 (9) | 29 (10) | 32 (10) |

| Gender, male/female | 14/3 | 14/3 | 14/3 | 13/4 | 13/4 |

| Handedness, right/left/ambidextrous | 12/3/2 | 12/3/2 | 12/3/2 | 13/4/0 | 13/4/0 |

| Educational level,a mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Participants | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Parents | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Schizophrenia subtype, paranoid/undifferentiated | 10/7 | 10/7 | 10/7 | ||

| Illness duration, months: mean (s.d.) | 22 (24) | 33 (27) | 106 (43) | ||

| SANS, mean (s.d.) | 44 (12) | 33 (11) | 33 (12) | ||

| SAPS, mean (s.d.) | 35 (13) | 8 (8) | 7 (9) | ||

| LSPRS, mean (s.d.) | 128 (18) | ||||

| Scan period, months: mean (s.d.) | 9 (4) | 84 (31) | 43 (14) | ||

| Anterior cingulate, MRS: available/excluded/missing | 15/2/0 | 14/1/2 | 16/1/0 | 17/0/0 | 17/0/0 |

| Thalamus, MRS: available/excluded/missing | 16/1/0 | 12/3/2 | 17/0/0 | 17/0/0 | 16/1/0 |

| Voxel-based morphometry, available/excluded/missing | 17/0/0 | 15/0/2 | 17/0/0 | 17/0/0 | 17/0/0 |

Seventeen matched healthy volunteers (control group) were recruited by an advertisement distributed in London, Ontario, Canada. The control group was of comparable age, gender, handedness, education level and parental education level. Healthy volunteers were scanned twice (Con1, Con2); the mean interval between two assessments was approximately 43 months. Unfortunately, scanner replacement precluded longer follow-up in the control group. Participants having a history of alcohol misuse and/or drug misuse in the 2 years before the scan or head injuries were excluded. Nine healthy volunteers participated in our previous study. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 Thedemographic data aredisplayed inTable 1. All participants provided written informed consent according to the guidelines of the Review Board for the Health Sciences Research Involving Human Subjects at the University of Western Ontario.

Medication information is shown inTable 2. Five patients with schizophrenia had received antidepressants and/or benzodiazepines 1–10 days prior to their initial assessment but had not taken any antipsychotic medication. Twelve of the patients had not received any medication prior to their initial scan. All except one patient had been treated with atypical antipsychotics at the 10-month assessment. At the 80-month scan, four of the patients were not taking any medication. Two patients had been treated with typical antipsychotics and the remainder had been treated with atypical antipsychotics. For patients on antipsychotic treatment, chlorpromazine equivalent doses were calculated in our previous study. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 In addition to the medication listed inTable 2, three patients had been prescribed the following treatment: metaformin in one tablet for diabetes, salbutamol for asthma or paracetamol for pain relief. None of the healthy volunteers, except one participant who had taken multivitamins daily, took any medication or supplements 24 h prior to the date of the scan.

Table 2 Medication: daily dosage (schizophrenia group)

| Never-treated (n = 17) | 10-month assessment (n = 17) | 80-month assessment (n = 17) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (s.d.) dose, mg | n | Mean (s.d.) dose, mg | n | Mean (s.d.) dose, mg | |

| No medication | 12 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Antipsychotic | ||||||

| Haloperidol | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.3 (0.4) | ||

| Zuclopenthixol | 1 | 6.4 | ||||

| Risperidone | 5 | 3.7 (2.1) | 3 | 3.3 (2.1) | ||

| Olanzapine | 3 | 7.5 (2.5) | 3 | 26.7 (5.8) | ||

| Quetiapine | 3 | 300 (100) | 3 | 317 (275) | ||

| Ziprasidone | 2 | 100 (84.9) | ||||

| Clozapine | 2 | 300 (141) | ||||

| Antidepressant | ||||||

| Paroxetine | 1 | 30b | ||||

| Citalopram | 2 | 20 (0)b | ||||

| Sertraline | 1 | 50 | ||||

| Bupropion | 1 | 100 | ||||

| Benzodiazepine | ||||||

| Clonazepam | 1 | 4a | 3 | 0.8 (0.3) | 1 | 0.5 |

| Lorazepam | 3 | 2 (1.7)a | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| Zopiclone | 1 | 7.5a | ||||

| Benztropine | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1.5 (0.7) | ||

| CPZ eq,a mg/day | 196 (146) | 282 (285) | ||||

Imaging and spectroscopy

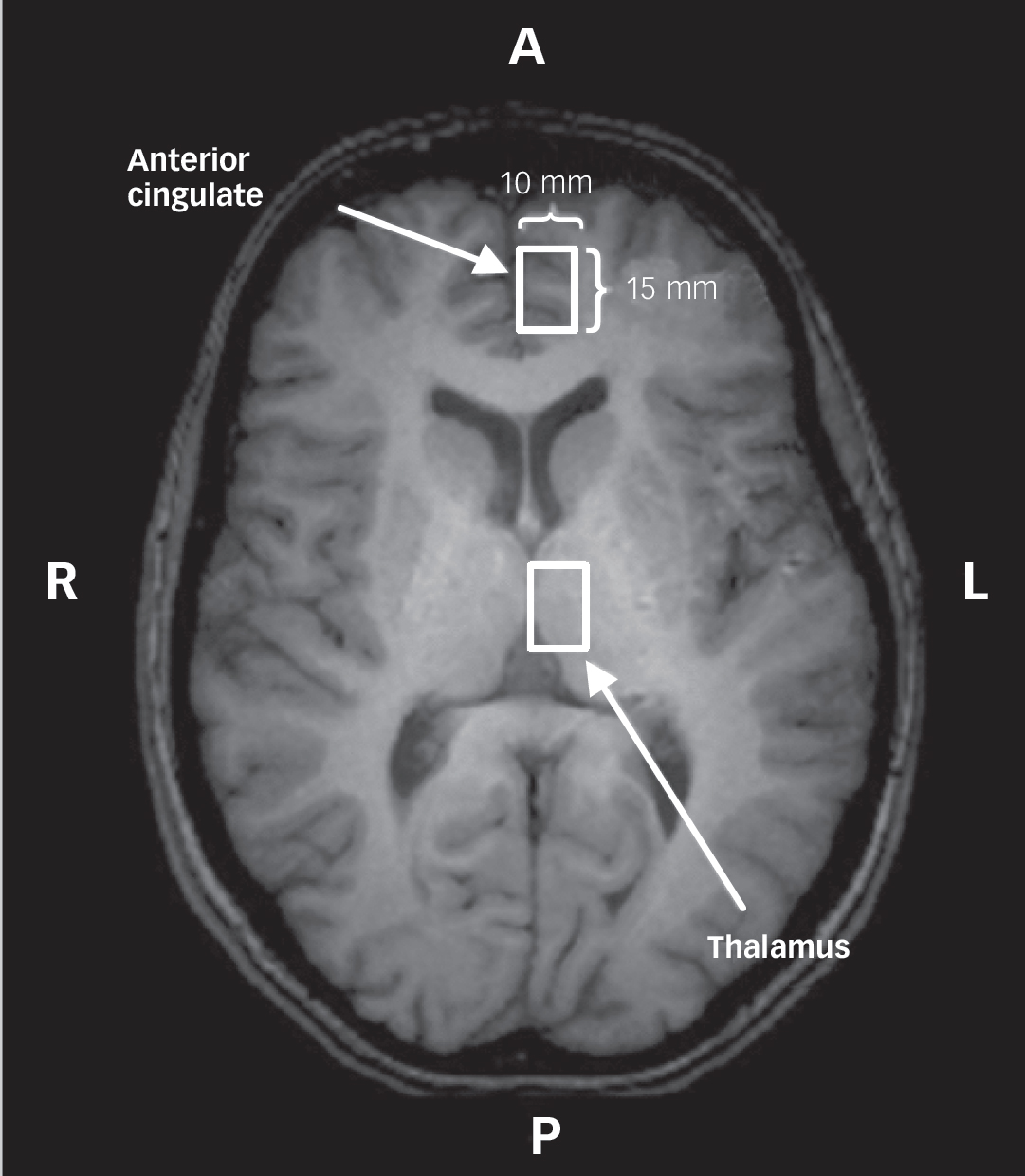

Data were acquired with a 4.0 T whole body magnetic resonance scanner located at the Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping of the Robarts Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada. A circularly polarised transmit/receive head coil was used. The magnetic resonance system was monitored by a technician, who performed weekly quality control using the same phantom and with the echo planner imaging sequence. All data acquisition and quantification procedures were performed as described in our previous study: Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 imaging, voxel positioning (left anterior cingulate and left thalamus;Fig. 1), voxel size (1.5 cm3), shimming, spectroscopy (STEAM sequence, echo time (TE) 20 ms, mixing time 30 ms, repetition time (TR) 2000 ms, dwell time 500 μs), pre-processing, exclusion criteria of magnetic resonance spectrum, spectral fitting and metabolite quantification. Only metabolites with a group coefficient of variation ((group standard deviation/group mean)×100%) less than 75% are reported: NAA, glutamate, glutamine, choline, total creatine (tCr), myo-inositol in the anterior cingulate and the thalamus; taurine and scyllo-inositol in the thalamus only. The ‘total glutamatergic metabolites’ (tGL) refers to a sum of glutamate and glutamine levels quantified individually. Complete description of the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and MRS methods can be found in the online data supplement.

Fig. 1 A white-coloured rectangle represents a spectroscopy voxel in the left anterior cingulate and the left thalamus.

Localisation was performed using a transverse T 1-weighted image, in which the landmark of each region is seen. A, anterior; L, left; P, posterior; R, right.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 17.0 for Windows. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with 2×2 split-plot factorial (SPF) design was conducted to investigate the data composed of two repeated measurements in two independent groups (never-treated and 80 months v. Con1 and Con2). The threshold was set at two-tailed alpha of 0.05 for glutamate, glutamine, tGL and NAA, conservatively inasmuch as the a priori hypotheses of their decrease over 80 months were unidirectional. A similar approach was used with a separate analysis entailing the three repeated measures for the schizophrenia group; however, the SPF design was replaced with a three-level repeated measures (within-participant only, randomised blocks) analysis (i.e. never-treated v. 10 months v. 80 months). An alpha of 0.05 was retained when comparing never-treated v. 80 months, as used in our previous findings, while alpha of 0.05 / 2 = 0.025 (two-tailed throughout) was applied for the two remaining pair-wise comparisons (never-treated v. 10 months, 10 months v. 80 months). Huynh–Feldt epsilon was used to adjust error-term degrees of freedom for repeated measures sphericity violations.

Regarding the other metabolites for which we did not have a priori hypotheses, a region-wise multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) using a 2×2 SPF design was applied with an alpha of 0.05; a univariate ANOVA on each metabolite followed a significant result of the multivariate level of analysis. Commensurate with our previous procedures, Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 within-participant analyses for the schizophrenia group comprised pair-wise MANOVAs, alpha being set at 0.05 / 3 = 0.0167 (to accommodate non-orthogonality of these comparisons) at both the multivariate and univariate levels, the latter analyses being contingent on multivariate-level significance.

Correlation analyses were performed between the metabolite levels of the schizophrenia group and their demographic information, clinical scales (SANS/SAPS), social functioning scale (LSPRS, 80 months only), length of illness and chlorpromazine equivalent dose with Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient. Threshold alpha was set at 0.001, with the exception of the hypothesised relationship between metabolites and LSPRS.

Voxel-based morphometry

Grey matter volume changes were measured with voxel-based morphometry Reference Ashburner and Friston16,Reference Ashburner and Friston17 on the three-dimensional T 1-weighted anatomical images using SPM2 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, University College London, UK) after normalisation as described elsewhere. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 General linear model with t-statistics was applied for statistical comparisons; unpaired t-tests were used for between-participant comparisons (Con1 v. never-treated, Con2 v. 80 months), and paired t-tests were used for repeated measures, within-participant comparisons (never-treated v. 10 months v. 80 months, three-level; Con1 v. Con2). The threshold for each test within each set of tests was established according to a multiple-comparison false discovery rate (FDR) corrected alpha of 0.001 with the extent threshold (cluster size k = 5). Correlation analysis between grey matter changes and two of the metabolites, glutamine and NAA, was performed with a test-wise alpha of 0.001. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8

Results

No significant change in the signal-to-noise ratio was detected in the weekly quality control throughout this study. A total of 168 magnetic resonance spectra (2 regions×(17 patients×3 time points + 17 controls×2 time points) – 2 missing data at 10-month assessment) were collected for this study. Nine of these spectra were excluded because of voluntary or involuntary movement such as excessive movement or breathing-related movement during the data acquisition. Glutamate and glutamine levels in the anterior cingulate from one patient with schizophrenia were excluded because the raw data for this participant at 80 months did not fit a glutamate and glutamine peak in this instance. However, the other metabolites were well resolved. Because of the non-physical values for glutamate and glutamine for this case, it was decided to include the other metabolites in the statistical analysis. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy results are shown inFig. 2, with the error bar representing the standard deviation of each group. As indicated inFig. 2, we were not able to follow up all individuals owing to technical and/or clinical reasons. Voxel-based morphometry data were analysed from 83 anatomical images (17 patients×3 time points–2 missing time points + 17 controls×2 time points) as shown inTable 1.

Between-participant comparison

A2×2 univariate SPF ANOVA on anterior cingulate glutamine yielded a significant group effect only (F = 5.04, d.f. = 1,28, P = 0.033). Note that this analysis was applied to 30 data-sets (13 patients and 17 controls) for which glutamate and glutamine were available at two time points. Analyses of NAA, glutamate and tGL levels yielded no statistically significant results. Multivariate and univariate tests did not evince significant effects for any other metabolite. In the thalamus, the univariate 2×2 SPF analysis did not reveal any group effect for NAA, glutamate, glutamine and tGL. For comparisons at the individual time points, glutamine level of the never-treated group was significantly higher than that of the Con1 group (t = 2.72, d.f. = 1,31, P = 0.011) as presented inFig. 2. Neither multivariate nor univariate tests revealed significant group effects in the other metabolites.

No significant grey matter difference between groups was observed at each time point at the FDR alpha of 0.001. Grey matter differences were only seen at an uncorrected alpha of 0.001; Con1 grey matter volume was greater than in the never-treated group in the left thalamus (x = –20, y = –24, z = 10, pulvinar, t = 3.71, d.f. = 1,32), Con2 grey matter volume was greater than the 80-month group in the left sub-lobar (x = –16, y = 28, z = 0, caudate body, t = 4.02, d.f. = 1,32) and left superior temporal gyrus (x = –66, y = –8, z = 2, Brodmann Area (BA) 22, t = 3.87, d.f. = 1,32).

Within-participant comparison (three-level)

Region-wise univariate three-level repeated measures analyses yielded no significant findings for NAA, glutamate, glutamine and tGL. Multivariate repeated measures in the other metabolites did not yield statistical significance in either the anterior cingulate (P = 0.083) or the thalamus (P = 0.034 > 0.0167).

Among the schizophrenia group, grey matter in the left anterior cingulate (x = –1, y = 53, z = 2, BA 24 and 32, t = 6.08, d.f. = 1,28) and the left thalamus (x = –12, y =–2, z =–2, t = 4.52, d.f. = 1,28) significantly diminished between the never-treated and the 80-month assessments.Figure 3 represents grey matter loss over 80 months. Significant decrease occurred with respect to the cross-sectional images of the T 1-weighted template, centred at the left thalamus. Significant loss was also observed in the frontal (BA 4, 10, 45 and 46), temporal (BA 21), parietal (BA 7), occipital (BA 18 and 30), limbic lobe (BA 24 and 30) and sub-lobar (putamen) regions. Significant grey matter loss between the 10-month and 80-month assessments was seen in the frontal lobe (BA 4, 6 and 9). All coordinates are listed inTable 3. No grey matter loss was observed at 10 months compared with the never-treated state.

Table 3 Voxel-based morphometry: significant grey matter loss with the three-level repeated measures in the schizophrenia group

| x | y | z | R/L | Lobe | Gyrus | BA/substructure | Cluster k a | Voxel t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never-treated > 80-month assessment (k = 5,corrected P<0.001, d.f. = 1,28) | 58 | 26 | 24 | R | Frontal | Inferior frontal | 45 | 61942 | 10.86 |

| 54 | 30 | 32 | R | Frontal | Middle frontal | 46 | 61942 | 10.78 | |

| – 26 | 62 | 4 | L | Frontal | Superior frontal | 10 | 61 | 4.69 | |

| – 50 | – 14 | 60 | L | Frontal | Precentral | 4 | 61942 | 10.86 | |

| – 56 | – 4 | – 24 | L | Temporal | Middle temporal | 21 | 146 | 4.79 | |

| – 12 | – 62 | 36 | L | Parietal | Precuneus | 7 | 991 | 6.11 | |

| 18 | – 62 | 30 | R | Occipital | Precuneus | 30 | 873 | 5.65 | |

| – 12 | – 86 | 22 | L | Occipital | Cuneus | 18 | 32 | 4.74 | |

| 14 | – 2 | 34 | R | Limbic | Cingulate | 24 | 1281 | 6.14 | |

| 16 | 10 | 32 | R | Limbic | Cingulate | 24 | 1281 | 5.40 | |

| – 18 | – 60 | 16 | L | Limbic | Posterior cingulate | 30 | 991 | 5.43 | |

| 22 | – 56 | 14 | R | Limbic | Posterior cingulate | 30 | 873 | 5.35 | |

| – 1 | 53 | 2 | L | Limbic | Anterior cingulate | 24, 32 | 61492 | 6.08 | |

| 12 | 54 | 10 | R | Limbic | Anterior cingulate | 24, 32 | 64492 | 6.89 | |

| 18 | 6 | 2 | R | Sub-lobar | Lentiform | Putamen | 275 | 5.42 | |

| – 12 | – 2 | – 2 | L | Sub-lobar | Thalamus | Ventral anterior | 49 | 4.52 | |

| 10-month assessment > 80-month assessment (k = 5, corrected P < 0.001, d.f. = 1,28) | 28 | 50 | 40 | R | Frontal | Superior frontal | 9 | 17 | 6.27 |

| – 46 | 6 | 58 | L | Frontal | Middle frontal | 6 | 5 | 6.10 | |

| 50 | – 14 | 62 | R | Frontal | Precentral | 4 | 14 | 5.94 |

Fig. 2 Metabolite levels measured in the left anterior cingulate and the left thalamus from healthy volunteers (Con1, Con2) and patients with schizophrenia (never-treated, 10 months and 80 months).

a, NT and 80 month higher than Con1 and Con2, 2×2 split-plot factorial analysis in group effect; b, Significant reduction from Con1 to Con2 in two-tailed paired t-test; c, 2×2 SPF analysis in group×time interaction; d, significant reduction from 10 month to 80 month in two-tailed paired t-test; e, significantly higher level in NT than in Con1 in two-tailed unpaired t-test; f, Con2 and 80 month higher than Con1 and NT, 2×2 split-plot factorial analysis in time effect; g, significant reduction from 10 month to 80 month in two-tailed paired t-test. Cho, choline; Con1, healthy volunteers at the initial assessment; Con2, follow-up examination for the healthy volunteers; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; NAA, N-acetylaspartate; NT, never-treated; Myo, myo-inositol; Syl, scyllo-inositol; Tau, taurine; tCr, total creatine; tGL, sum of glutamate and glutamine; 10 mo, 10-month assessment; 80 mo, 80-month assessment.

Within-participant comparison (two-level)

Within the univariate 2×2 SPF layout, no significant time effect or group×time interaction was found in NAA, glutamate, glutamine and tGL in the anterior cingulate. In a paired comparison, a non-significant trend towards a decrease in NAA level from 10 months to 80 months was found (t = 2.44, d.f. = 1,12, P = 0.031). The MANOVA on the remaining metabolites yielded no statistically significant results. A significant univariate group×time interaction was found for myo-inositol (F = 5.01, d.f. = 1,29, P = 0.033), resulting from a significant decrease over time in the control group (t = 2.51, d.f. = 1,16, P = 0.023). In the absence of statistical significance at the multivariate level of analysis, like the non-significant univariate-analysis trend above, this local result should be considered with caution. It nevertheless is reported for possible future consideration.

Fig. 3 Grey matter loss from never-treated state to 80-month assessment in the schizophrenia group with three-level repeated measures (false discovery rate corrected P<0.001).

Significant reductions represented as colour region are superimposed onto the cross-sectional T 1-weighted template images. The colour bar represents the t-value. The light blue cursor in the images was placed in the left thalamus (x = –12, y = – 2, z = –2, Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates).

Thalamic NAA, glutamate, glutamine and tGL did not show significant effects with respect to either time or group×time sources in the univariate 2×2 SPF analysis. There was a trend towards a decreased glutamine level at 80 months compared with the never-treated measure (t = 1.82, d.f = 1,15, P = 0.089), while tGL significantly decreased between the never-treated and the 80-month assessments (t = 2.20, d.f. = 1,15, P = 0.044). An example of glutamate and glutamine components as well as the fit spectra are presented in online Fig. DS2. Thalamic NAA of the schizophrenia group at 80 months significantly decreased from measured levels at 10 months (t = 2.97, d.f. = 1,11, P = 0.013). The 2×2 SPF MANOVA revealed a significant time effect in the remaining metabolites (F = 2.84, d.f. = 5,26, P = 0.035). The significant multivariate effect was paralleled by a significant univariate time effect for choline (F = 4.19, d.f. = 1,30, P = 0.049). There was a trend to increasing choline level at 80 months compared with the never-treated measure (t = 1.87, d.f. = 1,15, P = 0.080) but no significant change was observed between Con1 and Con2. No significant grey matter loss was found in the control group between their two scans (Con1 v. Con2).

Correlations

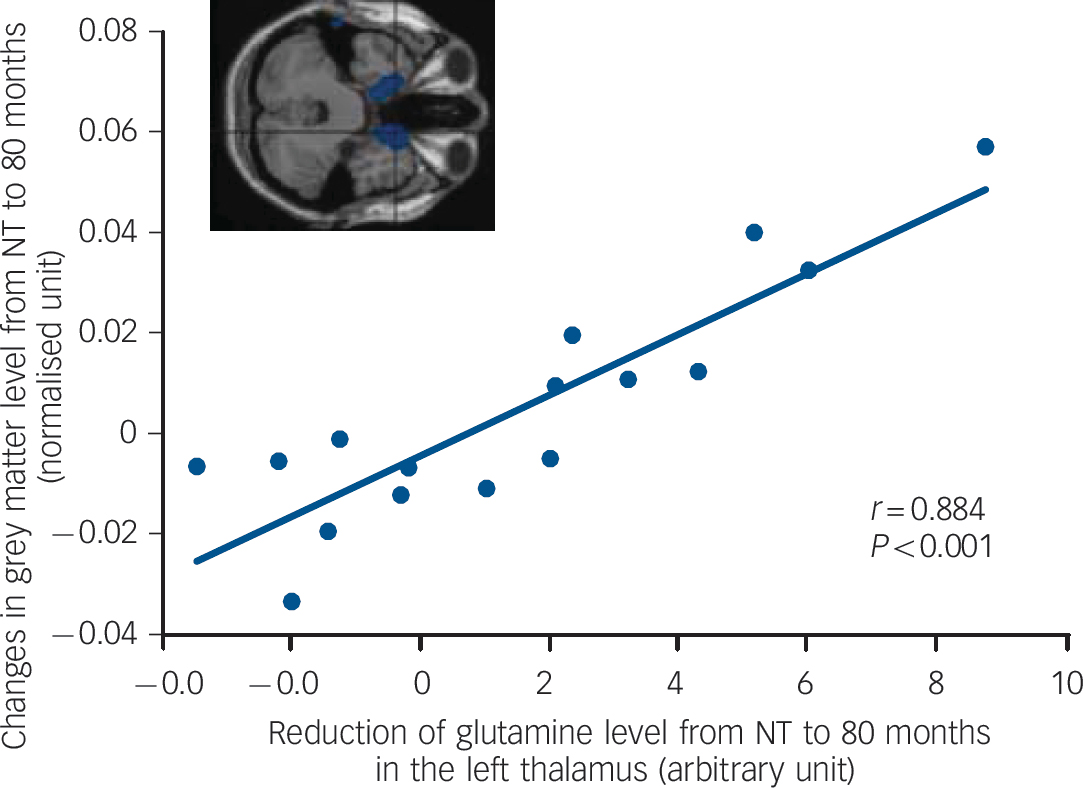

Correlation between grey matter reduction and loss of thalamic glutamine over 80 months was found in the ventral regions such as the right temporal pole (x = 16, y = 14, z =–34, BA 38, r = 0.884, P<0.001), presented inFig. 4. The detailed area is listed inTable 4. N-acetylaspartate reduction over 80 months in the left anterior cingulate correlated with the grey matter loss in the posterior regions, listed inTable 5. Reference Gardner and Neufeld18 Figure 5 represents the correlation between NAA loss and grey matter reduction in the right inferior parietal lobule (x = 62, y = 40, z = 28, BA 40, r = 0.841, P<0.001). The correlation between the losses of grey matter and either glutamine in the anterior cingulate, NAA in the thalamus, or tGL in both regions did not reach the P<0.001 level. Among the changes in metabolites, the losses in NAA and tGL levels between 10 months and 80 months tended to be positively correlated in the anterior cingulate (r = 0.625, P = 0.025, n = 13).

Table 4 Voxel-based morphometry: positive correlation between grey matter loss and glutamine loss in the left thalamus from never-treated to 80 months

| x | y | z | R/L | Lobe | Gyrus | BA/substructure | Voxel k a | Voxel t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – 10 | 66 | – 12 | L | Frontal | Superior frontal | 11 | 493 | 5.96 |

| 6 | 68 | – 14 | R | Frontal | Superior frontal | 11 | 493 | 5.11 |

| 42 | 34 | – 4 | R | Frontal | Middle frontal | 47 | 199 | 5.35 |

| – 44 | 34 | – 4 | L | Frontal | Middle frontal | 47 | 11 | 4.26 |

| 30 | 32 | 2 | R | Frontal | Inferior frontal | 47 | 199 | 5.06 |

| – 14 | 16 | – 14 | L | Frontal | Subcallosal | 47 | 51 | 4.62 |

| 16 | 14 | – 34 | R | Temporal | Superior temporal | 38 | 529 | 7.09 |

| – 70 | – 34 | – 18 | L | Temporal | Middle temporal | 21 | 676 | 4.97 |

| – 30 | – 64 | 34 | L | Parietal | Angular | 39 | 13 | 4.08 |

| – 12 | 6 | – 34 | L | Limbic | Uncus | 28 | 370 | 5.07 |

Table 5 Voxel-based morphometry: positive correlation between grey matter loss and NAA loss in the left anterior cingulate from never-treated to 80 months

| x | y | z | R/L | Lobe | Gyrus | BA/substructure | Voxel k a | Voxel t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – 32 | 22 | 58 | L | Frontal | Superior frontal | 8 | 7 | 4.52 |

| 56 | 8 | 34 | R | Frontal | Inferior frontal | 9 | 287 | 7.15 |

| 56 | 42 | 4 | R | Frontal | Inferior frontal | 46 | 148 | 6.14 |

| 62 | 52 | 2 | R | Frontal | Inferior frontal | 46 | 148 | 4.56 |

| 36 | 16 | 60 | R | Frontal | Middle frontal | 6 | 27 | 4.55 |

| 56 | – 8 | 46 | R | Frontal | Precentral | 4 | 287 | 5.58 |

| – 44 | – 64 | 54 | L | Parietal | Superior parietal | 7 | 1720 | 8.48 |

| – 30 | – 56 | 68 | L | Parietal | Superior parietal | 7 | 1720 | 7.87 |

| 16 | – 74 | 62 | R | Parietal | Superior parietal | 7 | 752 | 5.65 |

| 54 | – 40 | 52 | R | Parietal | Inferior parietal | 40 | 142 | 6.86 |

| 62 | – 40 | 28 | R | Parietal | Inferior parietal | 40 | 122 | 5.39 |

| 54 | – 48 | 50 | R | Parietal | Inferior parietal | 40 | 142 | 4.95 |

| 66 | – 36 | 38 | R | Parietal | Inferior parietal | 40 | 122 | 4.33 |

| 46 | – 68 | 46 | R | Parietal | Inferior parietal | 40 | 5 | 4.13 |

| – 50 | – 74 | – 34 | L | Parietal | Angular | 39 | 1720 | 7.24 |

| 16 | – 58 | 74 | R | Parietal | Postcentral | 7 | 752 | 7.47 |

| 56 | – 16 | 48 | R | Parietal | Postcentral | 3 | 287 | 5.09 |

| – 10 | – 68 | 40 | L | Parietal | Precuneus | 7 | 30 | 5.05 |

| – 18 | – 66 | 26 | L | Parietal | Precuneus | 7 | 30 | 4.57 |

| – 10 | – 74 | 48 | L | Parietal | Precuneus | 7 | 30 | 4.31 |

| – 12 | – 62 | 22 | L | Parietal | Precuneus | 31 | 30 | 3.96 |

| 22 | – 62 | 22 | R | Occipital | Precuneus | 31 | 285 | 6.55 |

| 12 | – 62 | 26 | R | Occipital | Precuneus | 31 | 285 | 4.95 |

| – 18 | 84 | – 2 | L | Occipital | Lingual | 17 | 230 | 6.04 |

| 28 | – 66 | 0 | R | Occipital | Lingual | 19 | 285 | 5.47 |

| 20 | – 96 | 14 | R | Occipital | Cuneus | 18 | 14 | 4.76 |

Fig. 4 Correlation between grey matter loss in the right temporal pole (x =16, y =14, z = –34, Brodmann Area 38) and reduction of thalamic glutamine from never-treated (NT) to 80-month assessment in schizophrenia.

Fig. 5 Correlation between grey matter loss in the right inferior parietal lobule (x =62, y =40, z = 28, Brodmann Area 40) and reduction of N-acetylaspartate (NAA) in the left anterior cingulate from never-treated (NT) to 80-month assessment in schizophrenia.

No correlation between loss of thalamic glutamine level and grey matter reduction was found between two measurements in the control group. The only significant correlation between anterior cingulate NAA reduction with grey matter loss in this group was found in a small cluster (voxel k = 5) in the middle frontal gyrus (x = 28, y =–14, z = 64, BA 6, r = 0.736, P<0.001).

Life Skills Profile Rating Scale scores at 80 months were negatively correlated with the loss of thalamic tGL between the never-treated and 80-month assessments (r = 0.694, P = 0.003) (Fig. 6). Significant correlation between chlorpromazine equivalent dose at 80-month assessment and grey matter loss between the never-treated and 80-month assessments was found in the bilateral temporal gyrus (x =–50, y =–44, z =–12, BA 37, r = 0.710; x = 48, y =–42, z =–8, BA 37, r = 0.704) at the P<0.001 level. No other correlations were found in the other metabolite levels with SANS/SAPS scores, length of illness, LSPRS scores or chlorpromazine equivalent dosage.

Discussion

Neurochemical alterations

Glutamine levels in never-treated patients were significantly higher than in controls in the left thalamus, in keeping with the previous reports, Reference Théberge, Bartha, Drost, Menon, Malla and Takhar5,Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 while levels in the anterior cingulate were not significantly different between groups, possibly because of higher standard deviations in the control samples. No differences were seen between never-treated patients and patients stabilised on medications, suggesting that antipsychotic medication did not affect glutamatergic metabolite levels.

Although we did not see a significant reduction in thalamic glutamine level over 80 months in schizophrenia, there was a significant decrease in the total glutamatergic metabolites (tGL), suggesting glutamatergic metabolism continues to decline with disease progression. This glutamatergic loss in the thalamus could also suggest a loss of neuropil in schizophrenia. This observation is consistent with the suggestion that excitotoxicity occurs primarily in the early stages of illness. Reference Jarskog, Glantz, Gilmore and Lieberman19 However, it is also possible that glutamatergic findings could be accounted for by alterations in the activity and density of glutamate dehydrogenase and glutamine synthetase, which have been reported to be anomalous in post-mortem schizophrenic brain extracts. Reference Burbaeva, Boksha, Turishcheva, Vorobyeva, Savushkina and Tereshkina20 The thalamic tGL reduction was inversely correlated with the LSPRS, suggesting a connection between glutamatergic neurophysiological changes and the impairment of social behaviour. It is of note that this correlation was found despite treatment with antipsychotic medications. Therefore, this finding indicates that the change in glutamatergic metabolites may be a potential indicator of the severity of schizophrenia in terms of social functioning.

Indeed, Tibbo et al Reference Tibbo, Hanstock, Valiakalayil and Allen21 reported a correlation between glutamate/glutamine ratio in the frontal cortex in adolescents at high risk for schizophrenia and Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores, suggesting that the glutamatergic changes are a candidate marker in the early stage of schizophrenia. Wood et al Reference Wood, Berger, Lambert, Conus, Velakoulis and Stuart22 reported a strong correlation between NAA/creatine ratio in the middle frontal gyrus in patients with psychosis and Social Functional Assessment Scale scores at 18-month follow-up. Although there are several differences such as the metabolite and its region compared with this study, they also suggest a connection between metabolites and functional outcome.

In addition to the glutamatergic findings, a reduction in the levels of NAA was found in both the left anterior cingulate (decreasing trend, P = 0.031) and the left thalamus (P = 0.013) between the 10-month and the 80-month assessments. These NAA deficits were not found to differ in a 30-month study. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 As NAA levels are generally thought to reflect neuronal integrity, this decline would be consistent with decreasing glutamatergic metabolite levels and possibly a loss of neuropil or limited apoptosis. Indeed, NAA and tGL reductions between the 10-month and 80-month assessments tended to be positively correlated in the anterior cingulate, suggesting that both metabolites may be related to neuropil loss. However, medication effects are also a possibility as NAA levels in never-treated patients were not statistically different from those in the same patients at 80-month follow-up.

No differences in glutamate, glutamine, tGL and NAA were seen in controls between baseline and follow-up scans. Those findings were consistent with the measurement at 30 months. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 However, controls in this study were not followed as long as patients because of decommissioning of the MRI system. This study had been running for over 12 years on the same MRI scanner. Compared at the latest assessment, glutamate and glutamine levels in the schizophrenia group were not significantly different from those in the control group. Decreased levels of both metabolites have been reported in the anterior cingulate in patients with chronic schizophrenia who had been ill in excess of 20 years. Reference Théberge, Al-Semaan, Williamson, Menon, Neufeld and Schaefer6 The lack of differences at 80 months between controls and patients implies that metabolite levels change more slowly over a considerable length of time.

Volumetric alterations

There was no significant difference between never-treated patients with schizophrenia and controls with the FDR corrected P<0.001 level, but some grey matter losses were observed with the uncorrected P<0.001 level in the thalamus, where a significantly higher glutamine level was found in schizophrenia. However, these differences were not to the extent expected if schizophrenic symptoms were due to a programmed loss of neuropil. Reference Selemon and Goldman-Rakic3

Fig. 6 Negative correlation between Life Skills Profile Rating Scale score at 80-month assessment and reduction of the total glutamatergic metabolites (tGL) in the thalamus from never-treated (NT) to 80-month assessment in schizophrenia.

Significant grey matter loss in patients with schizophrenia over 80 months was observed in many brain regions, including the anterior cingulate and the thalamus. This result suggests that it takes 7 years until grey matter losses are observable in many regions. Indeed, no reduction in the anterior cingulate and the thalamus was found during the 30 months of assessment in our previous report. Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 A grey matter reduction was also found in the frontal lobe in the schizophrenia group at 80 months compared with the never-treated assessment and the 10-month assessment, highlighting the importance of the frontal lobe in schizophrenia. There was no significant grey matter loss between the never-treated and 10-month assessments, suggesting that the acute effects of medication are minimal. Significant correlations between grey matter loss over 80 months and chlorpromazine equivalent dose were found only in the bilateral temporal gyrus, suggesting that medication is not likely the explanation for the widespread grey matter losses seen in these patients.

There was no significant grey matter loss in controls between the two assessments, implying aging effects are minimal. However, the mean scan period of controls was about 3.5 years, shorter than the patients’ scan period. No significant grey matter difference (FDR corrected P<0.001) was found in the comparison between CON2 and patients at 80 months. There were differences in the left superior temporal gyrus and caudate nucleus, albeit by more liberal criteria (uncorrected P<0.001), but which nevertheless are consistent with both our earlier study Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 and with another study. Reference Takahashi, Wood, Yung, Soulsby, McGorry and Suzuki23

Correlations between grey matter and metabolite losses at 80 months

The loss of thalamic glutamine in patients with schizophrenia was significantly correlated with grey matter loss in the middle and inferior frontal gyrus as well as in the temporal pole. A similar correlation between thalamic glutamate and grey matter loss in these regions was reported in individuals at risk of developing schizophrenia. Reference Stone, Day, Tsagaraki, Valli, McLean and Lythgoe24 Several prefrontal regions and the temporal pole are associated with social and emotional processing which may be deficient in patients with schizophrenia. Reference Bertrand, Sutton, Achim, Malla and LePage25,Reference Olson, Plotzker and Ezzyat26 As discussed in the previous section, social functioning on the LSPRS was negatively correlated with tGL loss in the thalamus in patients, suggesting that this correlation is mediated in part by these widespread structural changes. No correlations were found between losses of thalamic glutamine and grey matter in controls, suggesting that aging did not play a significant role.

The reduction of NAA in the anterior cingulate was significantly correlated with the grey matter loss over 80 months in posterior parietal areas. These areas are associated with attention, which many investigators have found to be altered in schizophrenia. Reference Cornblatt and Keilp27 These regions are also interconnected and form part of the default network associated with self-monitoring. Aberrant connectivity between the anterior portions of this network and other regions in patients with schizophrenia has been reported by our group and others. Reference Bluhm, Miller, Lanius, Osuch, Boksman and Neufeld28–Reference Neufeld, Boksman, Vollick, George and Carter30 Localised changes in these networks reflected by metabolic measures could lead to difficulties in self-monitoring which may underlie many symptoms of schizophrenia. Reference Williamson29 In contrast to multiple locations in schizophrenia, reduction in the anterior cingulate NAA levels in controls was only correlated with grey matter loss in the motor area. This cluster size was equal to the extent threshold, suggesting minimal correlation between neuronal integrity and neuropil in normal aging.

Excitotoxicity or plasticity

Although metabolite reductions, grey matter loss and their correlations over 80 months may suggest a neurodegenerative process in schizophrenia, there has been a debate about whether these anomalies are caused by excitotoxicity or plasticity. In contrast to our previous report, Reference Théberge, Williamson, Aoyama, Drost, Manchanda and Malla8 here, a loss of glutamatergic metabolites was observed in the thalamus concurrently with grey matter loss within the spectroscopic voxels (i.e. the anterior cingulate and the thalamus). If there is an excitotoxic process in schizophrenia, significant loss of grey matter in the thalamus might be expected in patients compared with controls at their initial assessment. However, there was no significant difference between these groups, suggesting that the changes in glutamatergic metabolites may be more sensitive to early changes not associated with grey matter loss.

Thalamic glutamatergic neurons are interconnected to all the cortical regions which were associated with grey matter loss in the schizophrenia group. They also form part of the basal ganglia–thalamocortical neuronal circuits implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Reference Alexander, Crutcher and DeLong31 Thus glutamatergic changes in the thalamus could be associated with glutamatergic changes throughout the cortex. Cortical grey matter losses could be accounted for by excitotoxicity into these regions. Increased membrane breakdown has been reported in patients with first-episode schizophrenia in a phosphorus MRS study. Reference Miller, Williamson, Jensen, Manchanda, Menon and Neufeld32 The decrease in NAA and decrease in grey matter over time in the anterior cingulate in this study would be compatible with this explanation. The trend to increased thalamic choline levels in patients at 80 months may also suggest excitotoxicity, as these levels reflect mostly membrane metabolites. A positive correlation between choline and the duration of untreated psychosis has been found in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Reference Théberge, Al-Semaan, Drost, Malla, Neufeld and Bartha33 However, it is possible that these circuits are simply being down-regulated, leading to plastic changes in grey matter and the metabolic changes.

Limitations

Although the absence of differences in metabolites and grey matter between the never-treated and 10-month assessments in patients argues against medication effects, the effects of exposure to medication can never be completely discounted, owing to the ethical unacceptability of conducting suitable trials. Another limitation may be the stability of the magnetic resonance scanner associated with the inevitable hardware replacements and/or upgrades that occur during such a long-term period, although the stability of our magnetic resonance system was carefully monitored through routine weekly quality control. We did not regularly calibrate the metabolite quantification. However, the metabolite levels were quantified with the internal water reference which minimises short- and long-term scanner drift. Owing to scanner replacement, we were unable to follow the control group for as long as the schizophrenia group. Consequently, we cannot exclude the possibility that controls may have had further NAA losses had we followed them longer. The lack of obvious changes in tGL between the two assessments in the control group suggests that aging alone would be unlikely to account for changes seen in patients at the 80-month assessment.

Funding

This work was supported by the Tanna Schulich Chair in Neuroscience and Mental Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant )

Acknowledgement

A part of this work was presented at the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Meeting in Toronto, Ontario, Canada (3–9 May 2008).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.