[T]he extent to which contemporary discourses, consciously or not, are affected by pre-modern paradigms is, at times, surprising.

In 1218, Jews in England were forced by law to wear badges on their chests, to set them apart from the rest of the English population. This is the earliest historical example of a country’s execution of the medieval Church’s demand, in Canon 68 of the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, that Jews and Muslims be set apart from Christians by a difference in dress. In 1222, 1253, and 1275, English rulings elaborated on this badge for the Jewish minority – who had to wear it (men and women at first, then children over the age of seven) – its size, its color, and how it was to be displayed on the chest in an adequately prominent fashion. In 1290, after a century of laws that eroded the economic, religious, occupational, social, and personal status of English Jews, Jewish communities were finally driven out of England en masse, marking the first permanent expulsion in Europe.1

Periodic extermination of Jews was also a repeating phenomenon in medieval Europe. In the so-called Popular and First Crusades, Jewish communities were massacred in the Rhineland, in Mainz, Cologne, Speyer, Worms, Regensburg, and several other cities. The Second Crusade saw more Jew-killing, and the so-called Shepherds’ Crusade of 1320 witnessed the genocidal decimation of Jewish communities in France. In England, a trail of blood followed the coronation of the famed hero of the Third Crusade, Richard Lionheart, in 1189, when Jews were slaughtered at Westminster, London, Lynn, Norwich, Stamford, Bury St. Edmunds, and York, as English chronicles attest.2

Scientific, medical, and theological treatises also argued that the bodies of Jews differed in nature from the bodies of Western Europeans who were Christian: Jewish bodies gave off a special fetid stench (the infamous foetor judaicus), and Jewish men bled uncontrollably from their nether parts, either annually, during Holy Week, or monthly, like menstruating women. Some authors held that Jewish bodies also came with horns and a tail, and for centuries popular belief circulated through the countries of the Latin West that Jews constitutionally needed to imbibe the blood of Christians, especially children, whom they periodically mutilated and tortured to death, especially little boys.3

Cultural practices across a range of registers also disclose historical thinking that pronounces decisively on the ethical, ontological, and moral value of black and white. The thirteenth-century encyclopedia of Bartholomeus Anglicus, De Proprietatibus Rerum (On the Properties of Things), offers a theory of climate in which cold lands produce white folk and hot lands produce black: white is, we are told, a visual marker of inner courage, while the men of Africa, possessing black faces, short bodies, and crisp hair, are “cowards of heart” and “guileful.”4

A carved tympanum on the north portal of the west façade of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Rouen (c. 1260) depicts the malevolent executioner of the sainted John the Baptist as an African phenotype (Figure 1), while an illustration in six scenes of Cantiga 186 of Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, commissioned by Alfonso X of Spain between 1252 and 1284, performs juridical vengeance on a black-faced Moor who is found in bed with his mistress; both are condemned to the flames, but the fair lady is miraculously saved by the Virgin Mary herself (Figure 2). Black is damned, white is saved. Black, of course, is the color of devils and demons, a color that sometimes extends to bodies demonically possessed, as demonstrated by an illustration from a Canterbury psalter, c. 1200 (Figure 3). In literature, malevolent black devilish Saracen enemies – sometimes of gigantic size – abound, especially in the chanson de geste and romance, genres that tap directly into the political imaginary, as some have argued.5

Figure 2. Illustration from Cantiga 186, Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, commissioned by Alfonso X of Spain. Escorial, Real Monasterio, Biblioteca, second half of the thirteenth century.

Figure 3. Healing of the Gadarene demoniacs. Psalter, folio 3v (detail), from Canterbury, c. 1200.

White is also the color of superior class and noble bloodlines. In the fourteenth-century Cursor Mundi, when four Saracens who are “blac and bla als led” (“black and blue-black as lead”) meet King David and are given three rods blessed by Moses to kiss, they transform from black to white upon kissing the rods, thus taking on, we are told, the hue of those of noble blood: “Als milk thair hide bicom sa quite/And o fre blode thai had the hew” (“Their skin became as white as milk/And they had the hue of noble blood” [Morris ll. 8072, 8120–1]). Elite human beings of the fourteenth century have a hue, and it is white. The few examples I cite here from medieval England, Germany, France, and Spain – examples from state and canon law, chronicles and historical documents, illuminations, encyclopedias, architecture, devotional texts, rumor and hearsay, and recreational literature – form only a miniscule cross-section of the cultural evidence across the countries of Western Europe.

Yet, in spite of all this – state experiments in tagging and herding people, and ruling on their bodies with the violence of law; exterminations of humans under repeating conditions, and disparagement of their bodies as repugnant, disabled, or monstrous; in spite of a system of knowledge and value that turns on a visual regime harvesting its truths from polarities of skin color, and moralizing on the superiority and inferiority of color and somatic difference – canonical race theory has found it difficult to see the European Middle Ages as the time of race, as racial time. Conditions such as these typically constitute race theory’s standard identifiers of race and racism, so it’s logical to ask: How is such obliviousness possible?

Canonical race theory understands “racial formation” (Omi and Winant 55) to occur only in modern time. Racial formation has been twinned with conditions of labor and capital in modernity such as plantation slavery and the slave trade, the rise of capitalism or bourgeois hegemony, or modern political formations such as the state and its apparatuses (we think of David Theo Goldberg’s magisterial The Racial State), nations and nationalisms (Étienne Balibar’s chapters in Race, Nation, Class), liberal politics (Uday Mehta), new discourses of class and social war (Foucault of the 1975–6 Collège de France lectures), colonialism and imperialism (the work of many of us in postcolonial studies), and globalism and transnational networks (Thomas Holt on race in the global economy).6

In the descriptions of modernity as racial time, a privileged status has been accorded to the Enlightenment and its spawn of racial technologies describing body and nature through pseudoscientific discourses pivoting on biology as the ground of essence, reference, and definition.7 So tenacious has been scientific racism’s account of race, with its entrenchment of high modernist racism as the template of all racisms, that it is still routinely understood, in everyday life and much of scholarship, that properly racial logic and behavior must invoke biology and the body as their referent, even if the immediate recourse is, say, to theories of climate or environment as the ground by which human difference is specified and evaluated.

In principle, race theory – whose brilliant practitioners are among the academy’s most formative and influential thinkers – understands, of course, that race has no singular or stable referent: that race is a structural relationship for the articulation and management of human differences, rather than a substantive content. Ann Stoler, a particularly incisive scholar of race, voices the common understanding of all when she affirms that “the concept of race is an ‘empty vacuum’ – an image both conveying [the] ‘chameleonic’ quality [of race] and [its] ability to ingest other ways of distinguishing social categories” (“Racial Histories” 191).

In principle, then, race studies after the mid-twentieth century, and particularly in the past three and a half decades, encourages a view of race as a blank that is contingently filled under an infinitely flexible range of historical pressures and occasions. The motility of race, as Stoler puts it, means that racial discourses are always both “new and renewed” through historical time (we think of the Jewish badge in premodernity and modernity), always “well-worn” and “innovative” (such as the type and scale of “final solutions” like expulsion and genocide), and “draw on the past” as they “harness themselves to new visions and projects.”8

The ability of racial logic to stalk and merge with other hierarchical systems – such as class, gender, or sexuality – also means that race can function as class (so that whiteness is the color of medieval nobility), as “ethnicity” and religion (Tutsis and Hutus in Rwanda, “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia), or as sexuality (seen in the suggestion raised at the height of AIDS hysteria in the 1980s that gay people should be rounded up and cordoned off, in the style of Japanese American internment camps in World War II). Indeed, the “transformational grammar” of race through time means that the current masks of race are now overwhelmingly cultural, as witnessed since September 11, 2001.9 Definitions of race in practice today at airport security checkpoints, in the news media, and in public political discourse flaunt ethnoracial categories decided on the basis of religious identity (“Muslims” being grouped as a de facto race), national or geopolitical origin (“Middle Easterners”), or membership in a linguistic community (Arabic-speakers standing in for Arabs).

But if our current moment of flexible definitions – a moment in which cultural race and racisms, and religious race, jostle alongside race-understood-as-somatic/biological determinations – uncannily renews key medieval instrumentalizations in the ordering of human relations, race theory’s examination of the past nonetheless stops at the door of modern time. A blind spot inhabits the otherwise extraordinary panorama of critical descriptions of race: a cognitive lag that makes theory unable to step back any further than the Renaissance, that makes it natural to consider the Middle Ages as somehow outside real time.

Like many a theoretical discourse, race theory is predicated on an unexamined narrative of temporality in the West: a grand récit that reifies modernity as telos and origin, and that, once installed, entrenches the delivery of a paradigmatic chronology of racial time through mechanisms of intellectual replication pervasive in the Western academy, and circulated globally. This global circulation project is not without its detractors, but the replication of its paradigmatic chronology is extraordinarily persistent, for reasons I outline below.

Race Theory and Its Fictions: Modernity as the Time of Race, an Old Story of Telos and Origin

In the grand récit of Western temporality, modernity is positioned simultaneously as a spectacular conclusion and a beginning: a teleological culmination that emerges from the ooze of a murkily long chronology by means of a temporal rupture – a big bang, if we like – that issues in a new historical instant. The material reality and expressive vocabulary of rupture is vouched for by symbolic phenomena of a highly dramatic kind – a Scientific Revolution, discoveries of race, the formation of nations, etc. – which signal the arrival of modern time. Medieval time, on the wrong side of rupture, is thus shunted aside as the detritus of a pre-Symbolic era falling outside the signifying systems issued by modernity, and reduced to the role of a historical trace undergirding the recitation of modernity’s arrival.

Thus fictionalized as a politically unintelligible time, because it lacks the signifying apparatus expressive of, and witnessing, modernity, medieval time is then absolved of the errors and atrocities of the modern, while its own errors and atrocities are shunted aside as essentially nonsignificative, without modern meaning, because occurring outside the conditions structuring intelligible discourse on, and participation in, modernity and its cultures. The replication of this template of temporality – one of the most durably stable intellectual replications in the West – is the basis for the replication of race theory’s exclusions.

For the West, modernity is an account of self-origin – how the West became the unique, vigorous, self-identical, and exceptional entity that it is, bearing a legacy – and burden – of superiority. Modernity is arrival: the Scientific Revolution, represented by a procession of founding fathers of conceptual and experimental science (Galileo, Descartes, Bacon, Locke, Newton) and the triumph of technology – the printing press ushering in mass culture, heavy artillery ushering in modern warfare.

Or arrival is attested by the Industrial Revolution, witnessing extraordinary per capita and total output economic growth of the Schumpeterian, over the Smithian, kind. Since origin is haunted in the post-Biblical West by the story of a fall from grace, modernity is also necessarily the time when new troubles arrive, the most enduring of which are race and racisms, colonization, and the rise of imperial powers. Regrettable as such phenomena are, their exclusive arrival in modern time (variously located) nonetheless sets off modern time as unique, special: confirming modernity as a time apart, newly minted, in human history.

The dominance of a linear model of temporality deeply invested in marking rupture and radical discontinuity thus eschews alternate views: a view of history, for instance, as a field of dynamic oscillations between ruptures and reinscriptions, or historical time as a matrix in which overlapping repetitions-with-change can occur, or an understanding that historical events may result from the action of multiple temporalities that are enfolded and coextant within a particular historical moment. The dominant model of a simple, linear temporality has geospatial and macrohistorical consequences. Since the prime movers and markers of modernity are exclusively or overwhelmingly discovered in the West, the non-West has long been saddled with the tag of being premodern: inserted within a developmental narrative whose trajectory positions the rest of the world as always catching up.

Some sociological historians and historians of science, working against the grain, have attempted to disrupt the narrative of scientific, economic, and demographic transformation separating modern from premodern time in the West, and the West from the rest.10 Revisiting the old repertoire of questions, they have argued for the legitimacy of complex, nonlinear temporalities: temporalities in which multiple modernities have recurred in different vectors of the world moving at different rates of speed within macrohistorical time. One position is articulated by Jack Goldstone’s thick description of human history as punctuated by scientific and technological “efflorescences” that, coupled with labor specialization and intensive market orientation, have driven both Schumpeterian and Smithian growth and change in various societies and various eras, thus muddying the monomythic simplicity of a radical break favoring the West in modernity’s singular arrival.

Against the putative uniqueness of the Industrial Revolution, we have Robert Hartwell’s data showing that the tonnage of coal burnt annually for iron production in eleventh-century northern China was already “roughly equivalent to 70% of the total amount of coal annually used by all metal workers in Great Britain at the beginning of the eighteenth century” (“Cycle” 122). Demographic patterns deemed characteristic of modernity have also appeared in premodernity. Goldstone observes that urban populations in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Europe – a period of extraordinary growth – amounted to 10 percent of the total population, a ratio not exceeded until the nineteenth century (347).

The work of Eric Jones and Robert Hartwell on the extensively developed water power, iron and steel industries, and shipping of Song China; that of Billy So on China’s mass-market industrial production of export ceramics; and that of Richard Britnell and Bruce Campbell, Joel Mokyr, D. S. L. Cardwell, Lynn White, and Goldstone himself on the economic and demographic growth, technology, urbanization, and commercialization of twelfth- and thirteenth-century Europe (Goldstone 380–9) furnish material for counternarratives contesting the fiction of sudden, unique arrival, and the discourse of Western exceptionalism.11 Some historians of science and sociology accordingly prefer to speak of scientific revolutions across time, rather than the Scientific Revolution – a single, unique instance, in a single unique modernity (Hart, Civilizations chapter 2; “Explanandum”) – and of industrial revolutions, rather than the Industrial Revolution.

Even were we to ignore the demographic, economic, and industrial materialities painstakingly tracked by these historians, the representation of medieval time as wholly foreign to, and unmarked by, modernity intuitively runs counter to the modes of understanding in contemporary theory undergirding the study of culture today. Studies of culture, literature, history, and art that have been open to late twentieth- and twenty-first-century developments in academic theory across the disciplines will not find unfamiliar the notion that the past is never completely past, but inhabits the present and haunts modernity and contemporary time in ways that estrange our present from itself.

Modernity and the present can thus be grasped as the habitat of multiple temporalities that braid together a complex and plural “now” that is internally self-divided and contaminated by premodern time. In public life, the evocation of Crusades and jihad by Jihadi and Salafi ideologues and by the Western political right after 9/11 is one example of the past in the present, marking an internal cleavage in modern time through which premodern time speaks itself as an active presence.12

Dipesh Chakrabarty’s meditation on how an earlier time reinscribes itself in later periods (always with difference, never in exactly the same way) is useful here:

humans from any other period … are always in some sense our contemporaries: that would have to be the condition under which we can even begin to treat them as intelligible to us … the writing of medieval history for Europe depends on this assumed contemporaneity of the medieval [with our present], or … the non-contemporaneity of the present with itself.

If we grant that the present can be nonidentical to itself in this way, we should also grant the corollary: that the past can also be nonidentical to itself, inhabited too by that which was out of its time – marked by modernities that estrange medieval time in ways that render medieval practices legible in modern terms.

If we allow our field of vision to hatch open these moments in premodernity that seem to signal the activity of varied modernities in deep time (Goldstone’s “efflorescences”), our expanded vision will yield windows on the past that allow for a reconfigured understanding of earlier time. Indeed, hatching open such moments in premodernity is what feminists and queer studies scholars have, in a sense, been doing for decades in staking out their European Middle Ages – identifying the instances in which a different consciousness and practice erupt and effloresce – even as their earliest archeologies suffered slings and arrows hurled in the name of anachronism and presentism. The “contemporaneity of the medieval” with our time, and the nonidentity of medieval time with itself, thus grants a pivot from which the recloning of old narratives can be resisted.

Nonetheless, at present the discussion of premodern race continues to be handicapped by the invocation of axioms that reproduce a familiar story in which mature forms of race and racisms, arriving in modern political time, are heralded by a shadowplay of inauthentic rehearsals characterizing the prepolitical, premodern past. For discussions of race, the terms and conditions set by this narrative of bifurcated polarities vested in modernity-as-origin have meant that the tenacity, duration, and malleability of race, racial practices, and racial institutions have failed to be adequately understood or recognized. With centuries elided, the long history of race-ing has been foreshortened, truncated to an abridged narrative.

But why would we want a long history of race? Like other theoretical-political endeavors that have addressed the past – feminism comes readily to mind as a predecessor moment; queer studies is another – the project of revising our understanding by inserting premodernity into conversations on race is closely dogged by accusations of presentism, anachronism, reification, and the like.13 Why call something race, when many old terms – “ethnocentrism,” “xenophobia,” “premodern discriminations,” “prejudice,” “chauvinism,” even “fear of otherness and difference” – have been used comfortably for so long to characterize the genocides, brutalizations, executions, and mass expulsions of the medieval period?

The short answer is that the use of the term race continues to bear witness to important strategic, epistemological, and political commitments not adequately served by the invocation of categories of greater generality (such as otherness or difference) or greater benignity in our understanding of human culture and society. Not to use the term race would be to sustain the reproduction of a certain kind of past, while keeping the door shut to tools, analyses, and resources that can name the past differently. Studies of “otherness” and “difference” in the Middle Ages – which are now increasingly frequent – must then continue to dance around words they dare not use; concepts, tools, and resources that are closed off; and meanings that only exist as lacunae.

Or, to put it another way: the refusal of race destigmatizes the impacts and consequences of certain laws, acts, practices, and institutions in the medieval period, so that we cannot name them for what they are, and makes it impossible to bear adequate witness to the full meaning of the manifestations and phenomena they install. The unavailability of race thus often colludes in relegating such manifestations to an epiphenomenal status, enabling omissions that have, among other things, facilitated the entrenchment and reproduction of a certain kind of foundational historiography in the academy and beyond.

To cite one example: How often do standard (“mainstream”) histories of England discuss as constitutive to the formation of English identity, or to the nation of England, the mass expulsion of Jews in 1290; the marking of the Jewish population with badges for three quarters of a century; decimations of Jewish communities by mob violence; statutory laws ruling over where Jews were allowed to live; monitory apparatuses like the Jewish Exchequer and the network of registries created by England to track the behavior and lives of Jews; or popular lies and rumors like the cultural fiction of ritual murder, which facilitated the legal execution of Jews by the state? That the lives of English Jews were constitutive, not incidental, to the formation of England’s history and collective identity – that the built landscape of England itself, with its cathedrals, abbeys, fortifications, homes, and cities, was dependent on English Jews – is not a story often heard in foundational historiography.14 Scholars who are invested in the archeology of a past in which alternate voices, lives, and histories are heard, beyond those canonically established as central by foundationalist studies, are thus not well served by evading the category of race and its trenchant vocabularies and tools of analysis.15

For race theorists, the study of racial emergence in the longue durée is also one means to understand if the configurations of power productive of race in modernity are, in fact, genuinely novel. Key propensities in history can be identified by examining premodernity: the modes of apparent necessity, configurations of power, and conditions of crisis that witness the harnessing of powerful dominant discourses – such as science or religion – to make fundamental distinctions among humans in processes to which we give the name of race.

A reissuing of the medieval past in ways that admit the ongoing interplay of that past with the present can therefore only recalibrate the urgencies of the present with greater precision. An important consideration in investigating the invention of race in medieval Europe (an invention that is always a reinvention) is also to grasp the ways in which homo europaeus – the European subject – emerges in part through racial grids produced from the twelfth through fifteenth centuries, and the significance of that emergence for understanding the unstable entity we call “the West” and its self-authorizing missions.16

Premodernists Write Back: Historicizing Alternate Pasts, Rethinking Race in Deep Time

Scholars who have considered race in premodernity have by and large understood race as arguments over nature – how human groups are identified through biological or somatic features deemed to be their durable or intrinsic characteristics, features which are then selectively moralized and interpreted to extrapolate continuities between the bodies, behaviors, and mentalities of the members of the group thus collectively identified. Premodernists subscribing to a view of race as contentions over nature have accordingly focused primary attention on bodies in examining the record of images, artifacts, and texts: investigating the meanings of skin color, phenotypes, blood purity and bloodlines, genealogy, physiognomy, heritability, and the impact of environment (including, in the medieval period, macrobian zones, astrology, and humoral theory) in shaping human bodies and human natures, with differential values being attached to groups thus differentially identified.

For antiquity, major studies by Frank Snowden, Benjamin Isaac, and David Goldenberg are among those that consider body-centered phenomena as indicators of race – and in particular, for Snowden and Goldenberg, blackness as a paramount marker of race.17 Among medievalists, noted studies by Robert Bartlett, Peter Biller, Steven Epstein, David Nirenberg, and contributors to a 2001 issue of the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies edited by Thomas Hahn also suggest that medievalists too have understood race as a body-centered phenomenon: defined by skin color, physiognomy, blood, genealogy, inheritance, etc.

Not all medievalists who have considered race believe the concept has purchase for the medieval period. Bartlett, for whom race pivots on biology, not culture, offers this caveat in his volume of 1993: “while the language of race – gens, natio, ‘blood,’ ‘stock,’ etc. – is biological, its medieval reality was almost entirely cultural” (Making of Europe 197). Bartlett’s subscription to the preeminence of biology in race matters wavers, however, when he grants that medieval practices which assume Jewish religious identity to be coterminous with ontological and essential nature can be considered racial (at least by other medievalists):

Many scholars see in the later Middle Ages a tendency for racial discrimination to become sharper and racial boundaries to be more shrilly asserted. The hardening of anti-Jewish feeling between the eleventh and the fifteenth centuries is recognized by all who work on the subject and they disagree only on their dating of the crucial change for the worse.

Bartlett’s later work (in 2001) continues his emphasis on biology, and attends to blood and descent groups in deciding race. For instance, because “environmental influence” is behind the thinking of Bartholomeus Anglicus and Albertus Magnus in their sorting of human kinds based on climatological determinism, Bartlett believes that their linking of skin color, physiognomy, and phenotype to dispositions of group character is not a racial dispensation, but an environmental one (“Medieval and Modern Concepts of Race and Ethnicity” 46–7). In his most recent work of 2009, “Illustrating Ethnicity in the Middle Ages,” Bartlett eschews race altogether in favor of “ethnicity.”

Peter Biller’s studies – among the most impressive and arresting work on medieval race today – focus on the evidence of medieval scientific texts, and on intellectual-pedagogical discourses circulating in medieval universities, in entrenching and diffusing theories of race. Steven Epstein, for whom “race/color” is a compound term (Purity Lost 9), scrutinizes the mixing of kinds in the eastern Mediterranean, and concludes that “back in the Middle Ages, color prejudice existed, at times even with few or no people of color to deprecate” (Purity Lost 13). In fact, the “literal valuing of people crossed beyond simple color symbolism or even prejudice into a way of thinking that closely resembled modern forms of racism, in a vocabulary suited to the times” (Purity Lost 201).

David Nirenberg’s interest in body-centered medieval race, based on evidence in Spain, has shifted in recent years: from earlier attention (in 2002) to Spanish historical events at the close of the Middle Ages that feature an obsession with blood purity, genealogical descent, and body-centered essential natures (“Mass Conversion and Genealogical Mentalities,” “Conversion, Sex, and Segregation”) to his more recent (2009) agnostic stance on medieval race, whether named explicitly as race or not (“Race and the Middle Ages,” “Was There Race Before Modernity?”).

Observing that “All racisms are attempts to ground discriminations, whether social, economic, or religious, in biology and reproduction. All claim a congruence of ‘cultural’ categories with ‘natural’ ones” (“Race” 74; “Before Modernity?” 235), Nirenberg concludes, “I am not making … claim[s] that race did exist in the Middle Ages, or that medieval people were racist. Such statements would be reductive and misleading, obscuring more than they reveal” (“Race” 74), and adds: “Nor do I aspire to anything so provincial as a proof that late medieval discriminations were racial” (“Before Modernity?” 239).

Nirenberg’s ambivalence (he simultaneously resists the notion that modernity is the sole context of race and inveighs against modernists who claim that race and racism are exclusively modern phenomena) may owe something to his conviction that “any history of race will be at best provocative and limited; at worst a reproduction of racial logic itself, in the form of a genealogy of ideas” (“Before Modernity?” 262).

Most contributors to Hahn’s issue – in particular Verkerk, J. J. Cohen, Lomperis, and Hahn himself (Kinoshita prefers “alterity” as her category of choice) – perform supple readings of literature and visual images within paradigms of body-centered race, focusing primarily on blackness and color as well as the exotic-foreign. In the same issue, William Jordan’s response (“Why Race?”) expresses a number of reservations, recommends attention to Jews rather than to color in medieval race, and offers the view that race paradigms may not be useful for the medieval period, especially when imaginative literature is mined for examples (much of the issue consists of literary readings).

Some premodernists have insisted that there must be prior linguistic evidence of the word “race” in European vocabularies before racial phenomena and racializing practices can exist, advocating priority for whether medieval peoples themselves saw themselves as belonging to races and practicing racisms. Insistence of this kind may underpin classicist Denise Buell’s scrupulous attentiveness to the meaning of the word genos in the early centuries of the Common Era, when strategies of Christian universalism rhetorically posit Christians as a new people, a kind of race (Why This New Race, “Early Christian Universalism”).18 As a reminder that a gap can exist between a practice and the linguistic utterance that names it, Steven Epstein’s discovery of “a way of thinking that closely resembled modern forms of racism, in a vocabulary suited to the times” (Purity Lost 201) suggests that “unfamiliar vocabularies and languages” (Purity Lost 13) do not in themselves indicate the absence of a phenomenon.

A few premodernists, following examples in critical race theory, have chosen to emphasize cultural and social determinants in racing – including a political hermeneutics of religion – while not eschewing overlapping multiple discourses in racial formation. Unlike many who stress nature-based determinants in racing, and race as body-centered phenomena, premodernists emphasizing sociocultural determinants do not assume that race or racism require human distinctions to be posited as permanent, stable, innate, fixed, or immutable.19

Critical race theory itself, of course, has for decades attentively scrutinized culturalist forms of racing – in which culture functions, we might say, as a kind of superstructure that is relatively disarticulated from its base, nature – without assuming that racial distinctions must be grasped as permanent or stable for racial categorizations to occur. Ann Stoler’s 1997 study of the colonial Dutch East Indies is a salient and oft-quoted example:

Race could never be a matter of physiology alone. Cultural competency in Dutch customs, a sense of ‘belonging’ in a Dutch cultural milieu … disaffiliation with things Javanese … domestic arrangements, parenting styles, and moral environment … were crucial to defining … who was to be considered European.

With the appearance of studies (like Gauri Viswanathan’s influential Outside the Fold) which point suggestively to how racial and religious identities might form interlocking and mutually constitutive categories,20 the examination of religion-based race has gained increased legitimacy among premodernists (see, especially, Buell; Heng [Empire of Magic, chapters 2 and 4; “Invention … 1” and “Invention … 2”; “Reinventing Race”]; Lampert, “Race”; Ziegler 198).

In the attempt to suggest how we might rethink the past, I should therefore begin with a modest, stripped-down working hypothesis: that “race” is one of the primary names we have – a name we retain for the strategic, epistemological, and political commitments it recognizes – attached to a repeating tendency, of the gravest import, to demarcate human beings through differences among humans that are selectively essentialized as absolute and fundamental, in order to distribute positions and powers differentially to human groups. Race-making thus operates as specific historical occasions in which strategic essentialisms are posited and assigned through a variety of practices and pressures, so as to construct a hierarchy of peoples for differential treatment. My understanding, thus, is that race is a structural relationship for the articulation and management of human differences, rather than a substantive content.

Since the differences selected for essentialism will vary in the longue durée – perhaps battening on bodies, physiognomy, and somatic attributes in one location; perhaps on social practices, religion, and culture in another; and perhaps on a multiplicity of interlocking discourses elsewhere – I will devote the rest of this introductory chapter to outlining architectures that support the instantiation of race in the medieval period, and to specifying key particularities – distinctive features – of medieval race, working where possible through actual examples. The use of concrete, particularized examples – a small spectrum which is not intended to be exhaustive, nor to duplicate the chapters that follow – will help to indicate how we might identify the varied locations and concretions of race in the Middle Ages, and sketch ways to consider medieval race without recourse to totalizing suppositions.

In addressing the nested discourses formative of race, it is important to note that religion – the paramount source of authority in the Middle Ages – can function both socioculturally and biopolitically: subjecting peoples of a detested faith, for instance, to a political theology that can biologize, define, and essentialize an entire community as fundamentally and absolutely different in an interknotted cluster of ways. Nature and the sociocultural should not thus be seen as bifurcated spheres in medieval race-formation: they often crisscross in the practices, institutions, fictions, and laws of a political – and a biopolitical – theology operationalized on the bodies and lives of individuals and groups.

Religious Race, Medieval Race: Jews as a Benchmark Example

Medievalists who study Jews will be familiar with my first example of how race emerges as an outcome of clustered forces and technologies. The infamous occasion described in this section issues from thirteenth-century England and is recorded and discussed in three contemporaneous Latin chronicles and an Anglo-Norman ballad, and has a tenacious afterlife for six-and-a-half centuries afterward. It is cited, elaborated, and transformed in drama and ballads, statuary and shrines, preaching and pilgrimage, books of private devotional prayer, miracle tales, etc., until the twentieth century, when a tourist pamphlet of 1911 invites (paid) viewing of the site at which the original atrocity allegedly occurred. The most influential historical account is by the thirteenth-century chronicler of St. Alban’s, Matthew Paris, and the finest aesthetic treatment in the Middle Ages is afforded by Chaucer, in the Prioress’s Tale of The Canterbury Tales.21

On July 31, 1255, in the city of Lincoln, an eight-year-old boy named Hugh, the son of a widow, Beatrice, fell into a cesspool attached to the house of a member of the Jewish community. There, “the body putrefied for some twenty-six days and rose to the surface to dismay Jews who had assembled from all over England to celebrate a marriage in an important family. They surreptitiously dropped the body in a well away from their houses where it was discovered on 29 August” (Langmuir, “Knight’s Tale” 461).22

The panicked behavior of the Jews who were gathered in Lincoln for the marriage of Belaset, daughter of Benedict fil’ Moses, poignantly expresses the sense of danger and fragility that characterized the quotidian existence of a minority community used to periodic violence from the majority population among which the minority community lived, and by which it was surrounded. Here, Jewish panic also issued from a frightened recognition of threat from a medieval technology of power against Jews, a techne that scholarship today calls the “ritual murder libel.”

In the standard plot of the libel, Jews were said to seize Christian boys of tender years, on the cusp of childhood, in order to torture, mutilate, and slaughter them in deliberate reenactments of the killing of Christ, for whose deicide Jews were held responsible. By 1255, ritual murder stories were well sedimented in English culture as a popular fantasy of Christian child martyrdom, a fantasy which had proliferating material results, since they installed a series of shrines for the Christian martyred that became public devotional sites around which feelings of Christian community could gather, pool, and intensify, bringing fame and pilgrims to the towns and cities in which the shrines were located.23

First invoked at Norwich in 1144, then Gloucester in 1168; Bury St. Edmunds in 1181; Bristol in 1183 or 1260; Winchester in 1192, 1225, 1232, and 1244; London in the 1260s and 1276; and Northampton in 1279, ritual murder libel – to be distinguished from its near-relative in anti-Semitic fiction, the blood libel, and its first cousin, host desecration libel – was the technology of power exercised against the hapless Jews of Lincoln in 1255.24 Consequently, on October 4, 1255, by order of Henry III of England, ninety-one Jews were imprisoned and one person executed for the “martyrdom” of Hugh. On November 22, eighteen more Jews were executed, “drawn through the streets of London before daybreak and hung on specially constructed gallows” (Langmuir, “Knight’s Tale” 477–8).25 Nineteen Jews were officially executed – murdered – by the state through acts of juridical rationality wielding a discourse of power compiled by communal consent over the generations against a minority target.

When state executions of group victims – unfortunates who were condemned by community fictions allowed to exercise juridical violence through law – occurred in the modern period, such official practices have been understood by race studies to constitute de facto acts of race: institutional crimes of a sanctioned, legal kind committed by the state against members of an internal population identified by their recognized membership within a targeted group. In the twentieth century, the phenomenon of legalized state violence occurred most notoriously, of course, under the regime of apartheid in South Africa. Today, Turkey’s systematic targeting of its minority Kurdish population for persecution and abuse offers an example of twenty-first-century-style apartheid and state racism.

In the United States, an example of state violence against a minority race might be Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, an order that created ten internment camps across seven states on the North American continent for the incarceration of 111,000 Japanese Americans during World War II, on the presumption that Japanese Americans constituted a community of internal aliens who would betray their country, the United States of America, to the enemy nation of Japan in wartime by virtue of their race.26

Were we to consider thirteenth-century enforcements of state power, which recognized Jews as an undifferentiated population collectively personifying difference and threat, alongside other state enforcements of homologous kinds that occurred in modern time, our aggregated perspective would likely yield an understanding that the legal murder of nineteen Jews in 1255 in England, on the basis of a community belief in Jewish guilt and malignity, constituted a racial act committed by the state against an internal minority population that had, over time, become racialized in the European West.

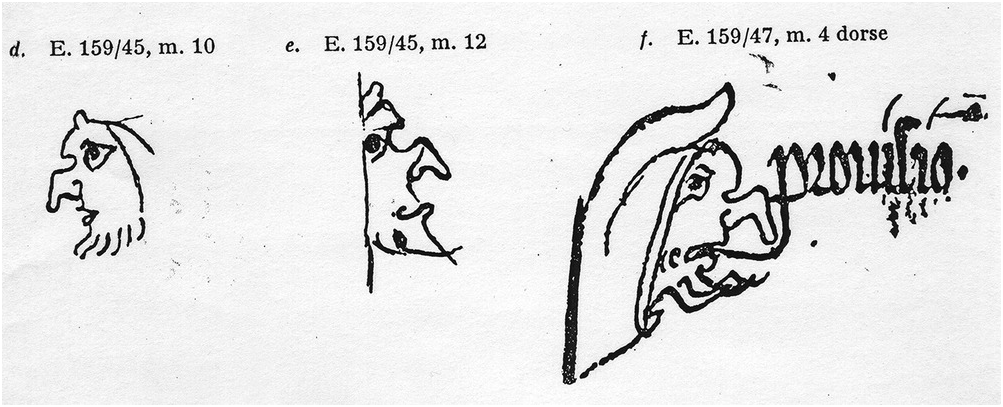

Jews were pivotal to England’s commercializing economy of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and constituted an immigrant community identifiable by virtue of religious and sociocultural practices, language, dress, and, occasionally, physical appearance (caricatures of Jewish phenotypes and biomarkers survive in English manuscript marginalia and visual art: see, for example, Figure 4).

Figure 4. The “Jewish face.” The King’s Remembrancer Memoranda Rolls, E.159, membranes 10, 12, 4 dorse. Public Record Office, thirteenth century.

Monitored by the state through an array of administrative apparatuses, and ruled upon by statutes, ordinances, and decrees, they were required to document their economic activity at special registries that tracked Jewish assets across a network of cities. No business could be lawfully transacted except at these registries, which came to determine where Jews could live and practice a livelihood. Jews needed official permission and licenses to establish or to change residence, and by 1275, the Statutum de Judeismo (Statute of Jewry) dictated that they could not live in any city without a registry by which they could be scrutinized, and they could not have Christians living in their midst – a thirteenth-century experiment in de facto segregation.

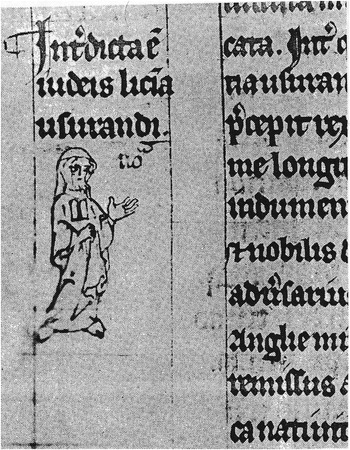

Subjected to a range of fiscal extortions and special, extraordinary taxations (tallages) which milked them to the edge of penury, Jews were barred from marriage with Christians, from holding public office, from eating with Christians or lingering in Christian homes, and even from praying too loudly in synagogues. They were required to wear large, identifying badges on their outer garments (Figure 5) and denied the freedoms of walking publicly in city streets during Holy Week and of emigration, as a community, without permission.

Figure 5. English Jew wearing the Jewish badge on his chest in the form of the tablets of the Old Testament. BL Cotton MS Nero, D2, fol.180, thirteenth century.

A special subset of government known as the Exchequer of the Jews was created to monitor and regulate their lives, residences, activities, and livelihoods. The constraints on their lives are too numerous to list; some would resonate eerily with the treatment of minority populations in other countries, and other eras, linking into relationship moments of medieval and modern time.

Robert Stacey observes that England’s example was “archetypical” of how Jews were treated throughout the countries of medieval Western Europe (“Twelfth Century” 340), differing mainly by virtue of the earliness, inventiveness, and intensity of English actions (Skinner 2).27 But the vast scholarship on Jews in medieval Europe specifies in excruciating detail more than state actions. Across a miscellany of archives, scholarship has tracked how Jews were systematically defined and set apart via biomarkers such as the possession of horns, a male menstrual flux or the generationally inherited New Testament curse of visceral-hemorrhoidal bleeding, an identifying stink (the infamous foetor judaicus), facial and somatic phenotypes (the facies judaica, “Jewish face”), and charges of bestiality, blasphemy, diabolism, deicide, vampirism, and cannibalism laid at their door through a hermeneutics of theology exercised by religious and laity alike across a wide range of learned and popular contexts.28

Instructive as legal, formal instruments of state control are as examples of ethnoracial practices, it is the extralegal and informal rehearsals of power that grant special traction and insight into medieval modalities of racial formation. For instance: The popular enthusiasm for community fictions of Jewish violence – stories of ritual murder and host desecration, blood libels; fictions that are designed to authorize and arrange for community violence to Jews – guides us to an important understanding that, for medieval Jews, it is equally the ritualized iteration of group practices that triumphantly enacts racial formation in the medieval period. Community fictions and community consent, periodically refreshed, augur performances that are ritually productive of race.

In England, then, the Jewish badge, expulsion order, legislative enforcements, surveillance and segregation, ritualized iterations of homicidal fables, and the legal execution of Jews are constitutive acts in the consolidation of a community of Christian English – otherwise internally fragmented and ranged along numerous divides – against a minority population that has, on these historical occasions and through these institutions and practices, entered into race.

Architectures of Racial Formation: Church and State, Law, Learning, Governmentality, Thirteenth to Fifteenth Centuries

I argued in my earlier book, Empire of Magic, that the medieval period of the long thirteenth century witnessed a motility in which seemingly opposed forces – universalizing measures set in motion by the Latin Church, in tandem with a partitioning, fractionalizing drive that powered nascent territorial nationalisms – furnished an array of instrumentalities for intensified collective identity-formation (68–73). In the drive for universality, the Church expanded modes of governmentality through exponential elaborations of canon law, circulating new orders of mendicant friars and inquisitions to root out heterodoxy, and systemically sought unity across internal divisions in the Latin West through uniform practices, institutions, sacraments, codes, rituals, and doctrines.29

Concomitantly, the West’s romance with empire that, from the end of the eleventh century, had seen overseas colonies (“Outremer”) established in the Near East for 200 years through the mass military incursions known as the Crusades, saw extraterritorial ambitions ramify from military expansionism to para- and extramilitary endeavors.30 Long before the territorial loss of the last crusader colony, Acre, in 1291, Dominicans and Franciscans had begun to diffuse worldwide a “soft power” vision of Latin Christianity from Maghrebi Africa to Mongol Eurasia, India to China, insinuating Christendom’s reach through missions, conversionary preaching, chapter houses, churches, and foreign-language schools for proselytes.31

Universalist ambitions are articulated in letters and embassies from popes and monarchs, ethnographic accounts and field reports, reconnaissance and diplomatic missions, offers of military and political alliances, and conversionary enterprises, the surviving evidence of which has become the miscellaneous records of Europe’s presence in the world.32 One (extreme) strain of universalist ambition is given voice by the English historian Matthew Paris, who conveys a high-ranking English churchman’s vision for Christian world domination when he vivaciously reports the Bishop of Winchester as saying, on the question of Mongols and Muslims, that England should leave the dogs to devour one another, so that they may all be consumed and perish; when Christians proceed against those who remain, they will slay the enemies of Christ and cleanse the face of the earth, so that the entire world will be subject to one Catholic church (Luard, Mathaei Parisiensis III: 489).

Scholars also point to congruent ambitions in this time such as the reordering of knowledge/power, as universities and scholasticism systematized learning and the reproduction of knowledge, encyclopedias retaxonomized the world, and compilations of summae sought to aggregate and systematize the totality of human understanding. More recently, scholars such as Peter Biller and Joseph Ziegler have emphasized how Greek and Arabic texts of science, medicine, and natural history – interpreted, modified, and circulated through university lectures and curricula after the energetic translation movements of the twelfth century – assembled a crucible of knowledge through which scientific, environmental, humoral, and physiognomic theories of race were delivered from antiquity to the Middle Ages.33

The Church’s bid for overarching authority and uniformity importantly furnished medieval societies with an array of models on how to consolidate unity, power, and collective identity across internal differences. A church with universalist ambitions in effect sought to function like a state, a state without borders: exercising control through a spectrum of supervisory apparatuses, laws, institutions, and symbols; homogenizing belief and coalescing communities of affect around uniform ritual practices; deploying mobile agents-at-large to police conformity within the Latin West and to gather information, extend diplomacy, and propagate doctrine without; and calling forth crusading armies from the countries of Europe at intervals for deployment in the ongoing competition with Islam for territorial, political, and cultural supremacy in the international arena.34

Functioning like a state without borders, a Church with universalist ambitions paradoxically also saw a swirl of contrapuntal forces in motion in the historical moment: a concomitant fractionalizing of collective identity in the form of emergent medieval-style nations characterized by intensive state formation and imagined local unities, as territorial nationalisms coalesced within Christendom.35

Nascent nationalisms also harnessed, and were powered by, expanded formal mechanisms such as law and informal mechanisms such as rituals, symbols, rumors, pilgrimage shrines, and affective communities mobilized by telling and retelling key stories of cultural power. In their mutual resort to overlapping resources, we can see how the interests of church and nation interlocked in logical relationship. Canon laws established by the Church to extend governmentality across territorial boundaries, such as Fourth Lateran’s Canon 68 requiring Jews to be publicly marked, also enabled the legal manipulation of Jewish populations within territorial boundaries: so that, in England, a distinctively English communal character was able to emerge through its posited difference from, and opposition to, the Jewish minority within England’s borders.36

Canon 68 thus in effect instantiates racial regime, and racial governance, in the Latin West through the force of law. It also bears witness to the rise of a political Christianity in the West that installs what Balibar calls “an interior frontier” within national borders, reinforced by affective cultures of fear and hate mobilized through stories of race like the ritual murder lie (“Racism and Nationalism” 42). The coalescence of England’s identity as a national body united across disparate (but always Christian and European) peoples thus pivoted on the politico-legal emergence of a visible and undifferentiated Jewish minority into race, under forms of racial governance supported by political Christianity, and sustained through the mobilization of affective communities enlisted by stories of race.

This is not to claim, of course – absurdly – that race-making throughout the medieval period is in any way uniform, homogenous, constant, stable, or free of contradiction or local differences across the countries of Europe in all localities, regions, and contexts through some three or four centuries of historical time. Neither is it to concede, in reverse, that local differences – variation in local practices and contexts – must always render it impossible to think translocally in the medieval period. The effort to think across the translocal does not require any supposition of the universal, static, unitary, or unvarying character of medieval race.

Indeed, in Invention of Race I point to particular moments and instances of how race is made, to indicate the exemplary, dynamic, and resourceful character of race-making under conditions of possibility, not to extract repetitions without difference. In this chapter, I point to homogenizing drives that universalize Christendom, and to fractionalizing drives that fragment Christendom into territorial nationalisms – such drives always manifesting themselves nonidentically and unevenly, in different places and at different times – to sketch the dynamic field of forces within which miscellaneous particularized instances of race-making can occur under varied local conditions. The remaining chapters of this book then take up skeins in the warp and weave of this matrix to outline some possibilities for further scholarly investigation.

The field of forces within which race-making occurs is also one of the operative grids through which homo europeaus cumulatively emerges over time.37 A modular feature disclosed by medieval elaborations is that race is a response to ambiguity, especially the ambiguity of identity: for among the “new visions and projects” to which the utility of race answers in this time are the specification of an authorized range of meanings for Latin Christian, European identity; the careful disarticulation of that identity-in-flux from its founding genealogies such as Judaism; and the securing of new moorings – including imperial moorings, launched by crusade and war, diplomacy, missions, and propagandizing – that answer to the ambitions and exigencies of the historical moment.

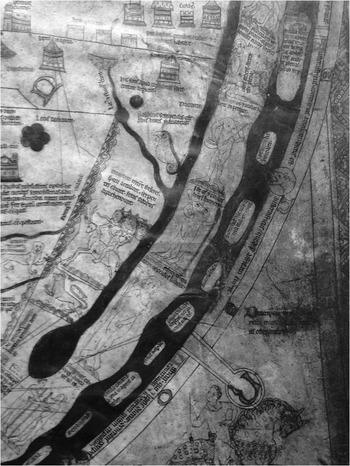

Cartographic Race: The Freakish, Deformed, and Disabled, or a Racial Map of the World in the Middle Ages

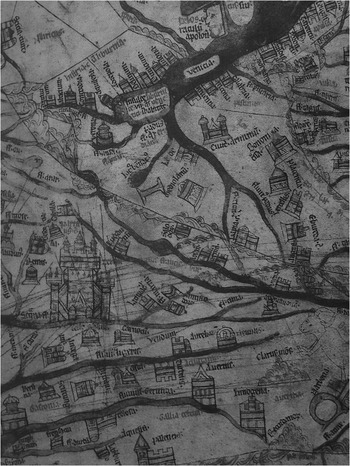

In the project of European identity, one of the most spectacular cultural creations of the medieval period – the mappamundi, or world map – hits its stride in the thirteenth century and after as a medium that visually unfolds an imagined universe of space-time which pictures the world in extraordinary ways that reflect on, and concretize, locations of race. A thirteenth-century mappamundi such as the richly detailed Hereford map, with its more than 500 pictures, 420 towns, 15 Biblical events, 5 scenes from classical mythology, 33 plants and animals, and 32 peoples of the earth puts on display the “cosmological, ethnographic, geographical, historical, theological and zoological state of the world” (Westrem, Hereford Map xv; Edson 142) by marking differences of place through the insertion of distinctive objects, narratives, and peoples that it locates into place as stakeholders for the meaning of a site.

For the territories of Europe, place is visualized on the Hereford by architectural features such as fortifications and cathedrals – the built environment of civilized urban centers – and bordered by natural features such as rivers (Figure 6). Outside Europe, however, geography is often dissected as ethnography, with places being identified as the habitat of human groups made distinct by the attribution of traits to them that are notable by virtue of their difference from normativity in the Latin West. Race is what the rest of the world has: Made visible and projected on a map through a human landscape, it indexes each vector of the world according to its relative distance from Europe in human, as well as spatial, terms. Rendered cartographically, the project of European identity, in surveying the world, sees Europe as the civilized territory of urban life – a web of cities – while global races swarm in other vectors of the world.

Figure 6. Western Europe with its cathedrals and fortifications, Hereford world map, Hereford Cathedral, thirteenth century.

In its most grotesque and spectacular forms, cartographic race equates with the monstrous races of semihumans located by the Hereford and other mappaemundi in Asia and Africa, and especially the coastline of southern Africa, which in the Hereford arrestingly teems with human monsters of many kinds (Figure 7).38 The depiction of pygmies, giants, hermaphrodites, troglodytes, cynocephali, sciapods, and other part-human, misshapen, deformed, and disabled peoples inherited from classical tradition harnesses the inheritance of the past to a medieval survey and anatomization of the world that reflects on the meaning and borders of European self-identity and civilization.

Scholars such as Scott Westrem (“Against Gog and Magog”) and Andrew Gow have found a close association between one particular monstrous race in mappaemundi – the unclean race of cannibals that was supposedly enclosed by Alexander the Great behind a barrier of mountains – and medieval Jews, also defined as unclean and monstrous by virtue of the blood libel. The eschatological tradition that the enclosed unclean descendants of Cain would break forth in the last days of the world to war on Christendom – supported by the tangible presence of those enclosed creatures visibly marked on mappaemundi – is thus doubly overwritten as a racial script that congeals the same external and internal racial target of accusation and fear.

Therefore, though much has been written about a uniquely different, medieval – which is to say, authentically unmodern – sense of the marvelous that celebrated “wondrous diversity” through prolific depictions of freaks and monsters in literature, art, and cartography, the insistence that medieval absorption with freakery and monstrosity is exuberantly different from modern absorption should not suggest to us that medieval pleasure should be seen as pleasure of a simply and wholly innocent kind.

Cartographic and imaginary race issued a grid through which European culture perceived and understood the global races and alien nations of the world. The “Monstrous Races tradition,” as Debra Strickland puts it, “provided the ideological infrastructure” for ruminating on and understanding “other types of ‘monsters,’ namely Ethiopians, Jews, Muslims, and Mongols” (42).

Gregory Guzman details how a race of Mongols, issuing from Central Asia, was understood by authors in the Latin West, including Matthew Paris, through a conceptual grid of the monstrous cannibal races of the world and their geographic locations. Equated with cannibalistic monsters cartographically found in northwest Asia are in fact a variety of historical races: Jews (in Mandeville’s Travels), Mongols (in the Chronica Majora of Matthew Paris), and Turks (in the Hereford mappamundi [Westrem, Hereford Map 137, Map section 4).

Finally, if there is a symbolic evocation on the Hereford of the relationship between race and chaos, it would be located in the largest single edifice on the map: an imposing Tower of Babel, key image in the Biblical narrative of the fabulous origin of proliferating human diversity, and a menacing reminder of incommensurate and unassimilable human difference – an edifice in the East that looms in immensity above the castles and cathedrals of Western Europe.

Politics of the Neighbor: Race, Conquest, and Colonization within Europe

But what of humans within Europe who share the most fundamental basis of identity in the Latin West: the European peoples of the Latin rite who are not monstrous aliens, nor Jews, Muslims, Mongols, Africans, pagans, heretics, schismatics, nor Greek or Eastern Christians, but neighbors living in proximity and bound by a common Latin Christian faith?

Studies of conquest and colonization in the countries of the “Celtic fringe” – a term ironized by medievalists, and which witnesses the unequal periphery-center relations that bound Wales, Scotland, and Ireland to the metropolitan hub of England – have pointed to English depictions of Celtic barbarity and subhumanness that were standard ideological tropes in England’s self-justification for its enterprise of occupying its neighbors.

Reflecting on Wales, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen sums up England’s colonial strategy: “An indigenous people are represented as primitive, subhuman, incomprehensible in order to render the taking of their lands unproblematic” (“Hybrids” 87). Though scholars differ on the legacy and intentions of English conquest, few disagree, given the documentary record, that the indigenous colonized were indeed portrayed by England as primitive and even subhuman.

Do such portrayals constitute race-making? A microhistorical example offered by Michael Goodich suggests that in the context of lived relations on the ground, a shared faith can sometimes bridge large enmities. Goodich shows how, in 1290, “when Wales was experiencing the baleful effects of forced colonization and Anglicization” by neighboring England, the attempted execution of a Welsh rebel named William Cragh, who miraculously survived death by hanging – a miracle he and others attributed to St. Thomas of Hereford (d. 1282) – resulted in conciliation between Welsh colonized and English colonizers. Pilgrimage to the English saint’s shrine by the subsequently pardoned Welsh ex-rebel, in the company of the local English lord and the lord’s wife and household, sealed “public recognition of a shared religious faith which could overcome political differences” (21).

“The religious cult,” Goodich concludes, “transcended … ethnic loyalties” (12), evincing “the power of the faith … to bring warring groups together …. Despite the destruction inflicted on Swansea and South Wales shortly before” by the English (21). Such Christian amity did not extend to those who were not coreligionists: St. Thomas himself, while bishop of Hereford, had supported the expulsion of Jews from England and confiscation of Jewish property “because they are ‘enemies of God and rebels against the faith’” (Goodich 21).39

If microhistory suggests that enmity between colonized and colonizers can sometimes be disengaged by a common religion and a shared religious ritual such as pilgrimage, microliterary example also attests to divisions not bridged by a common profession of the Latin Rite. Studies point to how Blind Hary’s nationalistic work of the 1470s, The Wallace, ferociously insists that essential differences of blood fundamentally separate English colonizers from native Scots resisters despite commonality of faith. R. James Goldstein stresses The Wallace’s use of “blood as an indicator of both class and race” (237), while Richard J. Moll shows how blood functions less as a genetic or genealogical category in The Wallace than as the binding glue of “true Scots” – defined as those who are loyal to the nationalist cause of Scotland’s independence, whatever their socioeconomic, personal, or group status (whether highlanders or lowlanders, etc.).40

Among neighbors in Latin Christendom, Ireland presents a resonant example of how even commonalities of faith can be adroitly manipulated to subserve colonial interests. English invasion and occupation of Ireland required a theological hermeneutic that insinuated difference of a fundamental kind between the Christianity of the colonized (rendered as inferior, defective, and deviant) and the Christianity of their Anglo-Norman colonizers (assumed as superior and normative).

No less than the magisterial Bernard of Clairvaux in his Vita Sancti Malachiae declared the Irish to be “uncivilized in their ways, godless in religion, barbarous in their law, obstinate as regards instruction, foul in their lives: Christians in name, pagans in fact” (qtd. in Bartlett, Gerald of Wales 169, emphasis added). Given that the Irish members of Latin Christendom were pagans in fact, Pope Adrian IV, writing to Henry II of England in 1155, could authorize the English monarch to occupy Ireland – a land that had converted to Christianity a century and a half before England itself – “with a view to enlarging the boundaries of the church … and for the increase of the Christian religion” (Muldoon, Identity 73).41

Exposition of a fundamental Irish difference in Christianity is accompanied by the elaboration of Irish socioeconomic difference and Irish cultural differences: Layer upon layer of negative judgments are nested in such a way as to discover a vast civilizational gulf between Ireland and England on a vertical axis of evolutionary development.

Ireland’s economic practices of transhumance signified backwardness, evidence that the Irish “have not progressed at all from the primitive habits of pastoral living,” as Gerald of Wales, the gifted chronicler and ethnographer who accompanied his Anglo-Norman masters from England to Ireland derisively put it in his Topographia Hiberniae (O’Meara 101; Brewer 5: 151).42 Labor in Ireland is transformed into a condition of lack – moralized as willful laziness and self-indulgence – and assigned to the character of an entire people: “[T]he soil of Ireland would be fertile if it did not lack the industry of the dedicated farmer; but the country has an uncivilized and barbarous people … lacking in laws and discipline, lazy in agriculture” (William of Newburgh, qtd. by R. R. Davies 124).43

The Irish people are … a people getting their living from animals alone and living like animals; a people who have not abandoned the first mode of living – the pastoral life. For when the order of mankind progressed from the woods to the fields and from the fields to towns and gatherings of citizens, this people spurned the labors of farming.

Even in the Middle Ages, we notice, modernity – symbolized by England as a poster child of agricultural cultivation; trade and commerce; urbanization; enlightened laws, usage, and custom; centralized state authority; and even the circulation of coin – is posited against a premodernity located in Ireland and rendered as a prior moment of human development that England had long since left behind.

Caricatured as a primitive land – an undeveloped global south lying to the west of England – Ireland was accordingly positioned as a project in need of evolutionary improvement and instruction, in order to force the “savage Irish” (“irrois savages” [Lydon, Lordship 283]) to emerge one day from their barbaric cocoon into a state of enlightened civilization – an agenda, Robert Bartlett observes, that “would not be out of place in nineteenth-century anthropological thought” (Gerald 176).45

The logic of evolutionary progress by which colonizers justify their extraterritoriality and craft their right to colonial rule – so much in evidence in later centuries in Africa, India, Southeast Asia, the West and East Indies, the Americas, and elsewhere – is pronouncedly a racial logic, and exercises “the language of colonial racism” (Bhabha 86). Racial logic of the evolutionary kind seems to promise (or even mandate) progress, yet racial logic’s ostensible goal of a subject population’s achievement of a civilizational maturity which will guarantee their equality with their colonial masters is never attained, but merely floats as a vaunted possibility on an ever-receding horizon.

The not-yet of racial evolutionary logic then becomes perpetual deferment, a “not yet forever” (Ghosh and Chakrabarty 148, 152). Thus we find four centuries later that England’s authors – Spenser’s A View of the Present State of Ireland is especially eloquent – are still derisively lamenting the premodern, backward, savage, uncivilized Irish.46

“So,” R. R. Davies wonders, “what was it … about the Irish which persuaded Edmund Spenser that they would never be able to reach that happy state [of English civility]?” (128). The clustering of virulent discourses on the Irish brings into focus processes of racialization that have little to do with skin color, physiognomy, phenotype, genealogy, blood lineage, macrobian zones, or climatology, but point instead to how flexible and resourceful strategies of race-making could be.

The Irish, after all, were Europeans and had converted to Latin Christianity much earlier than their colonizers, and Irish monasticism had famously helped to preserve the cultural record of the Latin West after the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire. Yet “[t]o be merus Hibernicus (‘pure Irish’) meant that one could never be the equal of an Englishman, whether one born in England or in Ireland” (Lydon, Lordship 288). Indeed, the Remonstrance of the Irish Princes, written in 1317 and addressed to Pope John XXII, describes how English laity and clergy alike “assert … that it is no more sin to kill an Irishman than a dog or any other brute” (qtd. by Lydon, Lordship 289, “Nation and Race” 109).47

The absence of physiognomic distinction that could enable Christian European groups to be visually distinguished from one another dictated a reliance on other regimes of visual inspection. Pointing to cultural cues to supply visual proofs of deep differences between Irish and English, Gerald of Wales, for one, makes much of the “flowing hair and beards” of the Irish, whose clothing is “made up in a barbarous fashion,” and whose warriors “go naked and unarmed into battle” (O’Meara 102, 101; Brewer 5: 153, 5: 151).

But the treacherous slipperiness of cultural markers, which can easily go astray and cue incorrectly, must be arrested, finally, by the force of law. Prohibitions of the infamous 1366 Statutes of Kilkenny – focusing on both Irish and English populations resident in Ireland – specially target those who, in their outward appearance, their manners, and their mores, enact the uneasy mixing of kinds: Anglo-Irish colonial settlers who have gone native and resemble the native population of Ireland.

Miscegenation – cultural, linguistic, sexual, and marital – is explicitly named in the opening statement of the 1366 legislation as the urgent animating imperative for issuing the Statutes. Enumerating the kinds of mixing that must not occur, the Statutes exhibit a particular distress at nativizing colonials who personify the unnerving difficulty of telling apart colonizers from colonized. The Statutes demand that every Anglo-Irish colonial settler “use the English custom, fashion, mode of riding and apparel” (Berry 434–5, emphasis added) because “many English … forsaking the English language, fashion, mode of riding, laws and usages, live and govern themselves according to the manners, fashion, and language of the Irish enemies; and also have made divers marriages and alliances between themselves and the Irish enemies” (Berry 430–1).

The Statutes of Kilkenny are rightly identified by scholars as racial law – legislating “a racial moment,” as Kathy Biddick puts it (“Cut” 453), in “the language of racism,” as James Lydon puts it (“Nation and Race” 106). Yet, issuing centuries after initial colonization, this edict merely ratifies rather than enacts race-making ab origo: “[t]he famously discriminatory 1366 Statutes of Kilkenny … merely codify a policy long pursued” (Hoffman 7).

Equally haunting is a story told by Gerald of Wales in his Topographia Hibernia, an anecdote that drives home both the horrors of miscegenation and the fate of the benighted Irish. Couched as a vignette about an old couple, a man and a woman of Ossory who are outwardly wolves but inwardly human, the story catches the eye of many because of its capacity for poignancy and shock, and for its evocation of the touching devotion of the aged couple and the pathos of their plight. An abbot’s curse has caused a human pair to live seven years as wolves; if they survive, the couple is released and replaced by another pair of humans who assume the burden of the curse for the next seven years, and so on, pair by pair, forever.

Narrated in detail and at far greater length than Gerald’s cursory accounts of Irish women copulating with goats or Irish men inseminating cows, this allegory of species miscegenation unfolds vividly in our mind’s eye as the old male wolf pleads with a priest to bless the female wolf – who is very ill and near death – with last rites and the Host. When the priest performs the rites but withholds communion, the old wolf, to prove that she is human and thus deserving of the Host, uses his paw to peel off the top half of her wolf form, from head down to the navel, shockingly disclosing an old woman beneath.48

A woman’s body thus proves the humanity of the wolf-couple – sexual difference emerging in the instant of confirming humanity, and issuing as the very ground of confirmation. The human voice alone, emerging from the jaws of a male wolf, has not been adequate to confirm humanness. A woman’s face, breasts, and navel are necessary – her navel also presenting proof of human predecessors before her. After she has “devoutly received the sacrament,” the skin is folded back again over the woman’s humanness, and the two wolves, sharing the priest’s fire all night long, depart in the morning, merely the latest pair to endure an unendurable destiny (O’Meara 75, 74, 70–2; Brewer 5: 101–3).

Like the people of Ireland who must bear the burden of imposed subhumanity in perpetuity while striving for admission to full humanity and civilization, the Irish werewolves of Gerald’s story are subhuman in perpetuity and live on the margins of the civilized world, as they ask for the most fundamental gifts of Christian humanity: sacraments and rites. Even if this individual pair survive their seven years of submergence into animalkind, these humans-who-are-wolves continue to be collectively cursed, doomed to subhumanity and outcast status forever. The story’s haunting ambience is delivered with wonderful little touches, like the lively presentation of the priest’s terrified incredulity, the human speech that startlingly emanates from the male wolf’s maw, and the old wolf’s desperation as he makes his plea for the dying female.

Finally, though the narrative concludes that “the wolf showed himself … to be a man rather than a beast” (72), we are left not with an image of the reassuringly human, nor one of the palpably animal, but with an impression of a profoundly tragic intermixture, and a relentless continuity without end. Through this strange presentation of a story that appeals at the level of affect and intuition, we absorb an allegory of colonial logic rendered as the fearful intermixing of kinds.

Irish appear like savage beasts on the outside, but may really be human under the skin. Their humanity, however, cannot be extricated from their animal nature, and even if some appear Christian, as witnessed by a touching faith in the highest of sacramental rites, the taking of the Host (a faith that confirms the power of those rites over all creation, universally), the Irish – as represented by these unfortunates of Ossory – are in the end tragic beings, mixing dual natures, at best doomed to pity, and forever denied access to full human and civilized status.49

The compassion elicited from us by this story and the poignancy that hovers over its narrative arc suggest alternative ways to read even colonial documents, if we attend to the queer residues that exceed the requirements of plot and trajectory. Like the Irish werewolves, Gerald’s text also appears at times to possess dual natures – evincing glimpses, here and there, of a tentative sympathy or wonder that abuts queerly against the more usual vitriol which the text aims at the Irish.

This story of tragic wolf-humans is not the only moment when the empire seems to write back in the interstices of the text or from the textual unconscious. In the annals of colonial documents where anticolonial discourse, oddly secreted in fissures, unexpectedly speaks, Gerald’s pithy report of the brief exchange between himself and the Irish Archbishop of Cashel (“a learned and discreet man,” says the text) can scarcely be bettered. To Gerald the narrator’s complacently superior remark deprecating Irish Christianity for lacking martyrs, given that “no one had ever in that kingdom won the crown of martyrdom in defence of the church of God” before, the Archbishop wryly responds:

“It is true” he said, “that although our people are very barbarous, uncivilized, and savage, nevertheless they have always paid great honor and reverence to churchmen, and they have never put out their hands against the saints of God. But now a people has come to the kingdom which knows how, and is accustomed, to make martyrs. From now on Ireland will have its martyrs, just as other countries.”

The sly civility of this Irish ecclesiastic – adverting to English atrocity to come, and a brave response by Irish resisters, all in the dulcet tones of the colonized but slippery and undefeated subject – belies the very barbarity the Archbishop so readily concedes as the identifying characteristic of his people. Gerald the narrator and Anglo-Norman enthusiast – so often described by scholars as obtuse, humorless, and tone-deaf – deadpans: “the archbishop gave a reply which cleverly got home – although it did not rebut my point” (O’Meara 115; Brewer 5: 178).50

In recent years, scholars have increasingly argued that “the experience of the English in Ireland … shaped the initial response of the English to the inhabitants of North America” (Muldoon, Identity 92):