Introduction

A leg ulcer is defined as the loss of skin below the knee on the leg or foot, which takes more than two weeks to heal (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Reference Moola, Munn, Tufanaru, Aromataris, Sears, Sfetcu, Currie, Qureshi, Mattis, Lisy and Mu2013). There are two main types of leg ulceration: venous and arterial. Venous leg ulceration is due to sustained venous hypertension, resulting from chronic venous insufficiency, whereas arterial leg ulceration is due to reduced arterial blood flow to the lower limb (Pannier and Rabe, 2013). In the UK population, the prevalence of leg ulcers is 0.56% (Guest et al., Reference Guest, Ayoub, McIlwraith, Uchegbu, Gerrish, Weidlich, Vowden and Vowden2015). Venous leg ulcers are ~30 times more prevalent than arterial conditions (Guest et al., Reference Guest, Ayoub, McIlwraith, Uchegbu, Gerrish, Weidlich, Vowden and Vowden2015). Leg ulcers are more frequent in women and incidences in the populace increase with age (Moffatt et al., Reference Mew2004). Management of chronic wounds is estimated to cost the National Health Service (NHS) between £2.5 and £3.1 billion per annum, accounting for 3–4% of the healthcare budget (Posnett et al., Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Bartlett, O’Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2009). Recent statistics reported that leg ulceration treatment costs the NHS £1.94 billion annually in 2012/2013, with higher incurred costs attributed to venous leg ulcers (£941 million) (Guest et al., Reference Guest, Ayoub, McIlwraith, Uchegbu, Gerrish, Weidlich, Vowden and Vowden2017).

A systematic review of 23 studies illustrated that venous leg ulceration negatively impacts patients’ quality of life (QoL), impairs functioning and mobility and reduces social activities due to their symptoms (Green et al., Reference Green, Jester, McKinley and Pooler2014). Gold standard treatment for venous leg ulcer involves compression therapy to reduce venous hypertension (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Reference Moola, Munn, Tufanaru, Aromataris, Sears, Sfetcu, Currie, Qureshi, Mattis, Lisy and Mu2013). Dressings are also required to prevent the bandage or compression hosiery from adhering to the wound (Royal College of Nursing, Reference Renyi and Hampton2000; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Reference Ryan and Hill2010). A major problem among patients with both venous leg ulcers is the lack of compliance with their long-term treatment regimens (Jull et al., Reference Jull, Mitchell, Arroll, Jones, Waters, Latta, Walker and Arroll2004; Raju et al., Reference Posnett, Gottrup, Lundgren and Saal2007) and compliance with leg ulcer treatment is acknowledged as an important determinant in leg ulcer healing and recurrence (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Lanza, Karp, Edwards, Seabrook, Cambria, Freischlag and Towne1995). The weak rapport between patients and clinicians appeared to negatively influence patients’ adherence and concordance to treatment (Douglas, Reference Douglas2001). Limited knowledge, poor communication and increased nurses’ caseloads were some of the reasons that patients’ perceived to restrict their engagement with their carers (Douglas, Reference Douglas2001). Lack of compliance to long-term treatment regimens was reported to hinder healing and prompt ulcer recurrence in patients with venous and arterial leg ulcers (Erickson et al., Reference Erickson, Lanza, Karp, Edwards, Seabrook, Cambria, Freischlag and Towne1995; Jull et al., Reference Jull, Mitchell, Arroll, Jones, Waters, Latta, Walker and Arroll2004). Although there is a growing awareness of the problem of non-adherence to leg ulcer treatment, reasons for non-adherence are not fully understood (Van Hecke et al., Reference Van Hecke, Verhaeghe, Grypdonck, Beele and Defloor2011). Pain, treatment discomfort and poor lifestyle advice from practitioners were highlighted as key reasons for non-adherence to leg ulcer treatment according to patients (Van Hecke et al., Reference Van Hecke, Grypdonck and Defloor2009). Specifically for venous ulcers, beliefs that compression are unnecessary and uncomfortable had a significant detrimental effect on concordance. In contrast, beliefs that compression are worthwhile and prevented recurrence improved concordance (Van Hecke et al., Reference Van Hecke, Grypdonck and Defloor2009). Furthermore, compliance to treatment may vary according to treatment types, with studies showing that patient-reported compliance is higher in patients allocated to class three stockings compared with short-stretch compression bandages (Van Hecke et al., Reference Van Hecke, Grypdonck and Defloor2008). Defining effective ways to improve compliance to treatment for leg ulcers is therefore essential to enhance treatment outcomes (Van Hecke et al., Reference Van Hecke, Grypdonck and Defloor2008).

Publication of the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline (CG) 168 on leg ulcers showed twofold increase in leg ulcer referrals (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Popplewell, Bate, Kelly, Darvall and Bradbury2017). A Cochrane review of seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) illustrated that compression use increases healing rates, and care delivery by specialist leg ulcer community clinics were superior to standard services offered by general practitioners (GP) and district nurses (Cullum et al., Reference Cullum, Nelson, Fletcher and Sheldon2001). Hence, seeking specialised services in leg ulcer care is apparent to optimise patient clinical outcomes.

The Leg Club is a social model of care established to provide holistic treatment to people with lower-limb ulcerations. The Leg Club model offers treatment in an informal community setting by trained district or community nurses, allowing patients to socially engage with others during their visits and collectively receive treatment, sharing their experiences and offering peer support. Unlike primary care services, no appointments are required, allowing flexibility to access care and provides a fully integrated ‘well leg’ component in their treatment plan (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2004). There are currently 30 Leg Clubs operating in the United Kingdom, eight in Australia and one in Germany (The Lindsay Leg Club Foundation, Reference Stephen-Haynes2018). Although new UK Leg Clubs have been established over the past 10 years, others have dissolved with growth hampered by insufficient evidence to inform clinical commissioning decisions. The clinical effects of a social model of wound care have not been well understood to-date. Given the high costs associated with delayed leg ulcer healing, evidence on the impacts and costs of the Leg Club model of care is warranted. This systematic review aims to identify published evidence on the impacts and quality of care of Leg Clubs on ulcer healing, psychosocial outcomes, patient safety and costs.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidance (Moher et al., Reference Moffatt, Franks, Doherty, Martin, Blewett and Ross2009) (Appendix 1). The authors searched Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Cinahl, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. The last search was performed on 28 March 2017. The search utilised various terms to define ‘leg ulcers’ that was previously published in a Cochrane systematic review (Weller et al., Reference Weller, Buchbinder and Johnston2016) in combination with ‘leg club’ to identify articles that addressed parameters pertaining to the Leg Club, including clinical responses, treatment safety, patient-reported outcomes, members’ experiences and economic impacts. The search strategy for Medline is shown in Appendix 2. Additional publications were identified through free-text searches on PubMed and Google Scholar, and reviewing the reference list of retrieved articles.

Selection criteria

Quantitative and qualitative data examining ulcer healing, psychosocial outcomes, economic evaluations, treatment safety and/or experiences of members of the Leg Club were considered for inclusion. No restriction on year or study design was applied during the selection process and only English-written articles were included. Two researchers reviewed titles, abstracts or full-text publications to assess their eligibility and relevance.

Data synthesis

No meta-analysis was performed due to heterogeneity of included studies and outcomes assessed. Hence, a narrative synthesis was conducted.

Quality assessment

Included studies were evaluated for their methodological rigour and/or transparency in reporting their findings. Six tools were utilised to assess quality due to variances in study designs, including the Cochrane Collaboration tool for RCTs (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher, Oxman, Savovic, Schulz, Weeks and Sterne2011), the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies (Lockwood et al., 2015), the JBI critical appraisal checklist for economic evaluation (Gomersall et al., Reference Gomersall, Jadotte, Xue, Lockwood, Riddle and Preda2015), the JBI critical appraisal checklist for case reports (Moola et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group2017), the mixed-method appraisal tool (Pluye et al., Reference Pannier and Rabe2011) or the quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies devised by the National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Health, 2014). No validated tools were available to evaluate audit reports. The overall quality of the study designs was rated as either good, fair or poor in accordance to each of the different assessment tool criteria. One author appraised the quality of each included study and another assessed 50% of the papers for accuracy. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

In addition, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the certainty of the evidence for each quantitative outcome, evaluating risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias, magnitude of effect, dose response and other plausible confounders (Ryan and Hill, 2016). Based on the GRADE system, the quality of the evidence was rated as high, moderate, low or very low. For qualitative studies, the Confidence in the Evidence for Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) was applied assessing methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy and relevance (Lewin et al., Reference Lewin, Booth, Glenton, Munthe-Kaas, Rashidian, Wainwright, Bohren, Tuncalp, Colvin, Garside, Carlsen, Langlois and Noyes2018). The confidence of each review finding was judged as high, moderate, low or very low. Three review authors independently assessed the quality of the findings. Disagreements were resolved through consensus.

Results

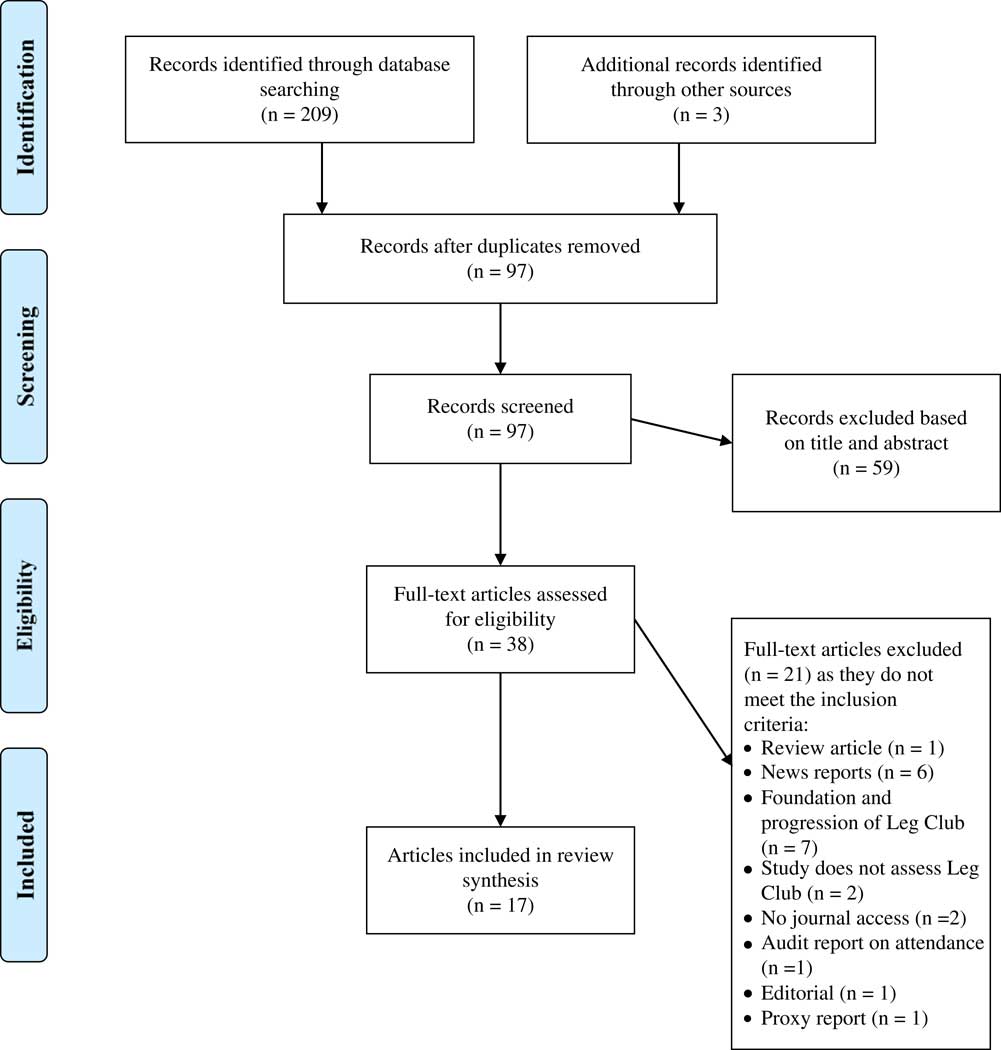

The literature search retrieved 212 citations, whereby 115 articles were identified as duplicates and remaining 97 publications were screened for relevance based on information in their titles and abstracts. Full-text manuscripts were assessed for their eligibility and 17 papers were deemed relevant. Four out of the 17 publications represent data from the same study. Most studies excluded discussed either the history and foundation of the Leg Club (n=7), or provided news update reports on the progression and achievements of the Leg Club (n=6) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Literature search using the PRISMA paradigm.

Overview of included studies

In this review, 17 publications representing 14 unique studies involving at least 532 participants were included, and the study characteristics are summarised in Table 1. In patients with leg ulcers, one RCT compared the effectiveness and assessed the health economics of standard care versus Leg Club (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lewis, Lindsay and Dumble2005a; Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lindsay, Lewis, Shuter and Chang2005b; Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2006), whereas most studies documented the experiences of Leg Club members using case reports (n=7) (Lindsay and Hawkins, Reference Lindsay and Hawkins2003; Hampton and Lindsay, Reference Hampton and Lindsay2005; Shuter et al., 2011; Mew, Reference Lockwood, Munn and Porritt2015; Renyi and Hampton, Reference Raju, Hollis and Neglen2015; Hampton, Reference Hampton2016; Wright, Reference Wright2016), mixed-method approaches (n=2) (Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013; Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton and Alexander2015), cross-sectional studies (n=2) (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2004; Clark, Reference Clark2012) or a qualitative method (Stephen-Haynes, Reference Shuter, Finlayson, Edwards, Courtney, Herbert and Lindsay2010). Moreover, two papers reported audit data on leg ulcer recurrence and healing rates, cost-savings and compliance to treatment (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2001; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013); 11 studies were conducted in the United Kingdom and three in Australia.

Table 1 Summary of included articles

RCT=randomised controlled trial; FU=follow-up; QoL=quality of life; ND=not determined; T1D=type 1 diabetes.

Quality appraisal of individual studies

The quality of included articles was evaluated using multiple tools due to heterogeneity of study designs. Information from RCTs and the health economics publication were deemed good quality with low risk of bias across most of the domains, including randomisation, reporting of outcomes and attrition. However, details on allocation concealment and blinding of assessors were ambiguous and blinding of participants was not possible. The qualitative study fulfilled all the assessment criteria, illustrating low risk of bias. Both cross-sectional studies were evaluated as poor quality due to inadequacy in methodological description, data analyses and lack of information on blinding of outcome assessors. One of the mixed-method studies was deemed fair and the other was evaluated as poor in quality, lacking information on sampling, attrition and study limitations. Moreover, both studies failed to address research bias in their methodology, affecting the credibility of their results. The results showed two out of eight case studies were judged as good quality, whereas four were evaluated as fair and one case report was appraised as poor quality. Case reports graded as fair or poor provided inadequate information on diagnostic tests and assessment methods. Nonetheless, all case studies provided clear details on medical history and clinical conditions of their participants. Given that this is an exploratory area of research, all relevant studies and audit reports, irrespective of study quality, were included and study limitations and potential sources of bias are highlighted in the discussion section.

Clinical impact of the Leg Club

Seven separate studies with a minimum of 209 participants assessed the clinical outcomes of leg ulcer patients attending the Leg Club, illustrating that treatment at the Leg Club may improve healing rates and may reduce ulcer recurrence (Lindsay and Hawkins, Reference Lindsay and Hawkins2003; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lewis, Lindsay and Dumble2005a; Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lindsay, Lewis, Shuter and Chang2005b; Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009; Hampton and Lindsay, Reference Hampton and Lindsay2005; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013; Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton and Alexander2015; Hampton, Reference Hampton2016; Wright, Reference Wright2016). A pilot and feasibility RCT conducted by the same group in Australia compared the effectiveness of the Leg Club to standard care demonstrating that the Leg Club model may be superior to home nursing visits with significant improvement in ulcer healing within 12 weeks, with 69–77% reduction in mean ulcer area versus 10–11% reduction, respectively (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lewis, Lindsay and Dumble2005a; Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lindsay, Lewis, Shuter and Chang2005b). Ulcer area was further significantly reduced at 24 weeks in both treatment groups (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009). Although, the healing rate was quicker in the intervention arm (0.267 cm2/week) than the control group (0.089 cm2/week) (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009). Ulcer healing at six months differed between Leg Club locations, whereby improvements were greater in Leg Clubs in Australia (60%) (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009) compared with United Kingdom (42%) (Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013). The overall quality of the evidence from the two RCTs is high, illustrating that the ulcer care at the Leg Clubs was associated with better health outcomes than usual care.

In one study, venous eczema and oedema were less prevalent in patients receiving treatment at the Leg Club than those offered standard care (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lewis, Lindsay and Dumble2005a), and an audit report from the Barnstaple Leg Club demonstrated that leg ulcer recurrence was low (Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013). Other variables evaluating ulcer care were gathered from testimonials from Leg Club members claiming that their ulcer wounds had improved or healed within 11–24 weeks (Lindsay and Hawkins, Reference Lindsay and Hawkins2003; Hampton and Lindsay, Reference Hampton and Lindsay2005; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013; Renyi and Hampton, Reference Raju, Hollis and Neglen2015; Hampton, Reference Hampton2016; Wright, Reference Wright2016). The small number of events in the analysis and the lack of a control group or comparator in these studies affect the credibility of the results, deeming the data insufficient to verify the impact of care from the Leg Club on ulcer recurrence.

Patient safety of Leg Club members

One RCT presented data on the incidence of a wound infection at 12 weeks in one leg ulcer patient receiving standard care; whilst one patient in the Leg Club intervention arm developed a new ulcer (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lewis, Lindsay and Dumble2005a). Audit data recorded over 11 months from two Leg Clubs in the United Kingdom (n=93) reported that none of their members presented any clinical infections (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2001). This was similarly noted in one case who attended a Leg Club in Australia for three years (Renyi and Hampton, Reference Raju, Hollis and Neglen2015). No other publications reported wound infections in their findings. Although the results are consistent across the three studies, the overall quality of the evidence from the RCT is low and very low for the non-RCTs, which is mainly due to the small number of participants investigated (n=127), increasing the probability of imprecision in the findings.

Patient-reported outcomes from Leg Club interventions

Evidence from four separate studies demonstrated that the Leg Club may enhance QoL, functional abilities, morale, mood and self-esteem (Lindsay and Hawkins, Reference Lindsay and Hawkins2003; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lindsay, Lewis, Shuter and Chang2005b; Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009; Shuter et al., 2011; Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton and Alexander2015). Decreased levels of pain were experienced by Leg Club patients, which may be directly associated with improved sleep, mood and normal working habits (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lindsay, Lewis, Shuter and Chang2005b). Social support and depression scores did not differ between the two arms at 24 weeks (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009). One questionnaire-based study reported that the Leg Club model may enhance patient understanding of their leg condition, which may help better manage their ulcer care (Clark, Reference Clark2012). Two studies illustrated that patients were compliant to treatment offered by the Leg Club (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2001; Hampton and Lindsay, Reference Hampton and Lindsay2005). However, no comparative control group was included in their study designs to determine whether different treatment modalities for leg ulcers influence patient compliance. Overall, the evidence is of low certainty due to the small number of total participants in the analysis.

In one study of 49 participants, more than 50% of members mentioned that attendance at the Leg Club improved their social situation and enhanced their well-being, which may have positively influenced treatment success (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton and Alexander2015). However, given that the evidence is very low quality, it is not certain whether there is a direct association between the social aspect of the Leg Club and ulcer healing.

Experience and perception of the Leg Club model: patients’ perspective

A total of 12 studies with at least 283 participants, mostly case reports (n=7), documented the experiences of Leg Club members assessing the impact of care delivery and model concept as a whole. Ten of these explored the views of UK patients (Lindsay and Hawkins, Reference Lindsay and Hawkins2003; Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2004; Hampton and Lindsay, Reference Hampton and Lindsay2005; Stephen-Haynes, Reference Shuter, Finlayson, Edwards, Courtney, Herbert and Lindsay2010; Shuter et al., 2011; Clark, Reference Clark2012; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013; Mew, Reference Lockwood, Munn and Porritt2015; Renyi and Hampton, Reference Raju, Hollis and Neglen2015; Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton and Alexander2015; Hampton, Reference Hampton2016; Wright, Reference Wright2016). Regardless of location, leg ulcer patients expressed positive views about the Leg Club, emphasising the advantage of peer support during the healing process (Hampton and Lindsay, Reference Hampton and Lindsay2005; Clark, Reference Clark2012; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013; Mew, Reference Lockwood, Munn and Porritt2015; Renyi and Hampton, Reference Raju, Hollis and Neglen2015; Hampton, Reference Hampton2016; Wright, Reference Wright2016). When compared with NHS facilities, more than 50% of members reported to attend the Leg Club because they enjoyed the social atmosphere and had more confidence in the advice and/or treatment received (Clark, Reference Clark2012). Moreover, 71 out of 86 current members rated that they were very satisfied with services received at the Leg Club (Clark, Reference Clark2012). Results from an interpretive phenomenological analyses of Leg Club attendees highlighted the importance of social interaction as well as the accessibility and continuity of care received at the Leg Club (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton and Alexander2015). These views were similarly echoed by participants from an explorative qualitative study with great emphasis on sociability and quality of care (Stephen-Haynes, Reference Shuter, Finlayson, Edwards, Courtney, Herbert and Lindsay2010). The Leg Club was described as friendly and welcoming, and attending patients appreciated the care and quality of services (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2004; Stephen-Haynes, Reference Shuter, Finlayson, Edwards, Courtney, Herbert and Lindsay2010; Shuter et al., 2011; Clark, Reference Clark2012; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013). Based on the CERQual assessment, the evidence on social interaction was considered moderate due to serious concerns regarding adequacy of data, whereas the confidence in the finding about the high quality of care in the Leg Clubs was considered low due to limited thin data from three studies, comprising qualitative components in their research, with moderate methodological limitations. Findings from five publications reported that patients regained their sense of purpose and had better control over their own lives, with greater ownership in their treatment plan (Lindsay and Hawkins, Reference Lindsay and Hawkins2003; Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2004; Shuter et al., 2011; Clark, Reference Clark2012; Wright, Reference Wright2016). Given that most of the evidence is derived from non-RCTs with a small number of participants, the overall quality of the observational studies is considered very low according to the GRADE framework.

Experience and perception of the Leg Club model: nurses’ perspective

There is very low quality evidence from one qualitative study exploring the views of healthcare providers (n=15) from two different Leg Clubs in the United Kingdom (Stephen-Haynes, Reference Shuter, Finlayson, Edwards, Courtney, Herbert and Lindsay2010). Overall, they described their jobs as ‘challenging’ and feeling ‘tired’. Nonetheless, they described the Leg Club as a hospitable environment for staff and clients. Common emerged themes derived from staff members included ‘education’, ‘camaraderie’ and ‘empowerment’, signifying a collaborative learning environment allowing both patients and staff to grow. Most importantly, nurses felt patients were empowered to take ownership in their treatment. The confidence in the evidence on the nurses’ perception was deemed moderate due to serious concerns of limited data derived from only one qualitative study.

Economic impact of the Leg Club

The moderate quality evidence from one RCT in Australia involving 67 participants demonstrated that the Leg Club probably incurs lower costs than home nurse visits by $1727 (approximately £1385) during a three-month period (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2006). Moreover, medical supply expenses were valued at 30% less for Leg Club compared with home nursing (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2006). Although total expenditure to the community for Leg Club was 20% higher than home nursing, the Leg Club leads to higher healing rates than standard care and had lower costs per healed ulcer during three ($1019 versus $1571) and six months ($1546 versus $2061). Overall, the Leg Club model appears to probably offer cost advantages over usual home nursing care (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2006). Only one UK audit report examining the total cost of wound management in patients attending the Leg Club during 11 months, and 73% of the population incurred £50, whereas 13% spent more than £200 to treat their condition (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2001).

Discussion

Quality of the evidence

This review considered the evidence from a wide range of study designs developed in two countries supporting the Leg Club model of care. The quality of findings ranged from moderate to very low across the different quantitative outcomes, and the confidence in qualitative findings was moderate to low primarily due to concerns in methodological design and data adequacy as assessed by CERQual. The main limiting factor that downgraded quality in most quantitative outcomes in accordance to the GRADE framework was the imprecision of results due to the small number of participants included in the analysis. Moreover, the lack of a comparator to evaluate the effectiveness of the Leg Club interventions is another limitation associated with most studies. Although, it can be argued that the evidence for clinical outcomes and patient-reported outcomes from the one RCT could be evaluated as moderate quality since a large magnitude effect and dose-response effect were illustrated. However, blinding of participants and outcome assessors were not possible in this RCT, and as such increases the probability of performance bias and detection bias. Moreover, inclusion of data from non-RCT studies exposes further risk of bias affecting the credibility of the overall results. Therefore, the evidence was assessed as low or very low quality for most outcomes.

Although the evidence is rich in diversity of outcomes, it is weak in providing robust scientific direction for healthcare commissioners who may wish to explore this model in community settings. The higher quality evidence showing improvements in ulcer healing and other patient-reported outcomes was from one underpowered RCT conducted in Australia. No experimental evidence exists for the majority of Leg Clubs operating in the United Kingdom. Australian findings may not be mirrored in the United Kingdom, such that healing rates in the United Kingdom were nearly two-thirds of that achieved in the Australian context (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013). However, no demographic information about the study population was described by Elster et al. (Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013), and as such it is not possible to compare patient characteristics from the two studies or draw any inferences on the factors that may influence the reported differences in healing rates between the Leg Clubs in the two countries. Whilst nurses reported positive working experiences and patient outcomes in the United Kingdom, differences between healthcare contexts in Australia and the United Kingdom require further investigation. Clinical practices, context and capacity of Leg Club location, nurse training and availability may influence the varied outcomes between the two countries.

Two studies found that treatment concordance improved during attendance at the Leg Club (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2001; Hampton and Lindsay, Reference Hampton and Lindsay2005). However, no correlative assessments were conducted to determine whether Leg Club attendance was positively associated with treatment concordance and what the mechanisms of increased concordance might be. NICE guidance recommends specialist community wound clinics over home-based GP/community nurse-led treatment (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Reference Moola, Munn, Tufanaru, Aromataris, Sears, Sfetcu, Currie, Qureshi, Mattis, Lisy and Mu2013). Future evaluations of the Leg Club in the United Kingdom need to be undertaken in this context where the comparator is one of current best practice such as a specialist community clinic. Treatment concordance has been found to improve in specialist multidisciplinary clinics compared to usual NHS care in other conditions (Van Groenendael et al., Reference Van Groenendael, Giacovazzi, Davison, Holtkemper, Huang, Wang, Parkinson, Barrett and Geberhiwot2015). The question of cost-effectiveness may be crucial in determining best practice for the management of chronic leg wounds in the community.

Strengths and limitations

Although our review identified relevant articles systematically, it was difficult to draw conclusive inferences due to variability in study designs and assessment tools. There were numerous limitations related to the studies, including minimal detail of sampling strategies, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and assessors, small sample sizes, and lack of clarity on study and analytic methods. Therefore, it was difficult to evaluate the validity and rigour of the findings. Furthermore, due to the nature of the methodology of surveys, audits and case reports, no comparators were included; thus rendering their data as inconclusive. In addition, the discrepancy in the different sample sizes reported from the same RCT could not be resolved despite attempts in contacting the authors. Consequently, we believe that the evidence published at different time points represent findings from preparatory work that includes single feasibility (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lewis, Lindsay and Dumble2005a) and pilot (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Lindsay, Lewis, Shuter and Chang2005b) testing stages, as well as data from the later full RCT (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Courtney, Finlayson, Shuter and Lindsay2009).

Implications for research

This review highlights the potential of the Leg Club social model of care to make contributions to reducing the burden for people with chronic leg wounds and the costs associated with these conditions. A few Leg Clubs are starting to be commissioned by NHS local commissioning groups who believe that the cost-savings and improvement in care demonstrated by local audits are convincing (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay2001; Elster et al., Reference Elster, Kingsley and Layton2013). NICE guidance relies on high-quality evidence, which is required of Leg Club care to enable commissioners and health professionals to make sound scientific and cost-effectiveness decisions on referral of patients presented with leg ulcers. The overall quality of the evidence is lacking and warrants future research using more robust RCT designs to determine the efficacy of Leg Club interventions on ulcer healing.

Conclusion

The Leg Club holds potential for providing cost-effective specialist community-based wound care. A fully powered UK RCT is needed with appropriate comparator groups to ascertain the value and contribution of Leg Clubs to the UK NHS.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

None.

Appendix 1: PRISMA checklist

Appendix 2: Search strategy in Medline

1. Exp Leg Ulcer/

2. varicose ulcer$.mp.

3. venous ulcer$.mp.

4. leg ulcer$.mp.

5. foot ulcer$.mp.

6. (feet adj ulcer$).mp.

7. stasis ulcer$.mp.

8. (lower extremit$ adj ulcer$).mp.

9. crural ulcer$.mp.

10. ulcus cruris.mp.

11. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 8 or 9 or 10

12. 12. ‘Leg Club’.mp.

13. 11. and 12.