In September 1965, presenter Ernst Hilger raised a laugh when he suggested to a live radio audience in Linz that he would translate effortlessly what his cohost in České Budějovice (Budweis) had just said to audiences across the border in Czech. Despite Hilger's ironic dig at the incomprehensibility of the Czech language, his joke indicated a degree of fellow feeling across borders between Austrians and citizens of Czechoslovakia. It came as part of a broadcast of Alle Neune, a radio game show coproduced by Austrian public broadcaster ORF's regional subsidiary in Linz and Czechoslovak Radio's local station in České Budějovice. The program, which aired on both state broadcasters, featured live audiences in both locations showing how much they knew about each other's culture—in one round, the Austrian and Czech teams both had to guess which Strauss waltz and Smetana polka they had just heard. Additional rounds of the game show (on famous Europeans, or canonical dramatic texts) pointed out how much both constituencies had in common.

The program was a celebration of radio technology and infrastructure—through radio, the inhabitants of České Budějovice could answer questions posed by people in Linz, and their answers could be heard in Prague and Vienna, where stations relayed the program. Listeners from both countries were encouraged to participate by mailing in their answers to a question posed especially for them; those who wrote in were promised a book, whether they correctly guessed the answer or not. One round of the game show paid homage to the Linz-České Budějovice railway—the first horse-drawn railway in Europe built in 1825. Although the railway was invoked as proof of Linz and České Budějovice's historic connection, the program demonstrated how the technology had been superseded and radio could now transfer information between the two locations more quickly. At the end, hosts Jiří Stuchal and Ernst Hilger concluded that radio built bridges, and guests in both locations clapped their approval.

Coproductions such as Alle Neune have been examined for what they show of changing international politics at the elite level during the Cold War.Footnote 1 But in the article that follows, I argue that Alle Neune constituted Czechoslovak and Austrian state endorsement of “grassroots” listening practices that both parties already knew existed (and that were not particular to the liberal 1960s). Czechs and Slovaks listened to German-language radio from Austria and West Germany in their thousands during the postwar period. By acknowledging officially the ways Czechoslovaks engaged with Austrian radio—through practices of listening, correspondence, and other forms of participation—Czechoslovak Radio sought to claim, through Alle Neune, some of these practices' popularity for itself. Thus institutional, infrastructural projects such as Alle Neune should not always be understood to constitute dirigiste attempts at shaping citizens’ perceptions and solidarities; by embarking on such projects, state actors could also take advantage of and formalize networks already created by their citizens.

The scale of Austrian and West German radio listening is made apparent in surveys conducted by Radio Free Europe (RFE) about listening habits in the Eastern Bloc. RFE reception polls throughout the 1960s found that Radio Vienna was the most popular foreign station with Czechoslovak listeners. The American-sponsored broadcaster instigating such surveys was, perhaps to its own analysts’ chagrin, frequently the runner-up to German-language radio in the contest for audiences. Such conclusions find reinforcement in the Communist Party's own reports from the 1950s and 1960s, and in the first systematic Czechoslovak radio polls from the end of the 1960s.Footnote 2 German-language radio listening thus emerges as a constant of radio's second “golden age” in Czechoslovakia, which spanned from the immediate postwar period until 1969. During this period, radio served as the leading medium to which audiences turned when making social and political claims on authorities.

Cross-border, German-language listening during the Cold War mattered, then, not only between the Germanies, but also in central Europe, where listening habits were shaped by the multilingual heritage of the region. Focusing on this, rather than on the experience of listening to RFE as most scholarship on foreign radio in Czechoslovakia has done to date, additionally reveals the enduring significance of German as a language of regional communication, the continued importance of cross-border contacts (in particular in border regions), and the significance of light entertainment in central Europe during the Cold War.

While the “ability to receive radio and television from neighboring countries was not specific to the case of divided Germany,” Frank Bösch and Cristoph Classen have claimed, “it had particular significance within the context of the German-German rivalry because there were no language or cultural barriers that had to be overcome.”Footnote 3 But historians have wrongly assumed linguistic barriers between citizens of different central European states in the postwar era. Instead, language barriers had to be created between Czechs, Slovaks, and Germans—which led to generational divides emerging among media users at the onset of the Cold War. Exploring first who listened to German-language radio, how, and when, this article overturns the notion that Europeans held linguistically homogenous media preferences after the Second World War. Czechs and Slovaks may have lived in an increasingly ethnically homogenous state, but they did not forget the languages they had learned in school and had used (no matter how grudgingly) in daily encounters with the state and other citizens during earlier regimes. Following this sketch of listening techniques and venues, a short section on language politics in postwar Czechoslovakia maps in more detail the rise and fall and rise of German as a language of regional communication.

I then turn to the way that radio was used by listeners in Czechoslovakia to maintain and rework cross-border contacts, especially in border zones. Analyzing Czechs’ and Slovaks’ experiences of listening to Austrian stations in particular, I show how their actions at once retooled cultural practices established under the Habsburg monarchy and reflected broader contemporary media consumption trends. Next, I take the Austrian driving show Autofahrer unterwegs as a case study in how Czechoslovak listeners remediated contact with German speakers. Finally, I investigate the significance of such light entertainment during the Cold War, returning to the game show Alle Neune.

Devised by ORF to celebrate “all nine” of Austria's federative states and their historic international connections, Alle Neune shows the enduring infrastructural importance of regional interchanges long beyond the demise of the Habsburg empire and into the Cold War. That Linz and České Budějovice (and not Prague and Vienna) were chosen for this high-profile production shows how infrastructures tend to, as Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski point out, reutilize former connections, “depending” on previous networks for their routes while creating new cultural, economic, and societal configurations.Footnote 4 The Linz-Budějovice nexus of this radio link also attests to the significance of provincial, borderland radio interconnections, which are frequently overlooked, argue Carolyn Birdsall and Joanna Walewska-Choptiany, in transnational radio histories, which wrongly “privilege radio produced by national broadcasters in capital cities, located at the heart of ‘media capital,’ and invested in reproducing the image of ‘media centrality.’”Footnote 5

If media histories rarely focus on borderlands as key sites of media use, then central and eastern European historiography frequently takes them as its focus. Czechoslovakia's postwar borderlands have been researched both as sites of ethnic cleansing and as a ground zero for communist modernization.Footnote 6 Revealing how local populations used foreign media (and modern technologies) to renegotiate their relationships with native German speakers, I qualify the extent to which the “new” societies forged in the borderlands following the war completely broke with past practices of association. I also question the characterization of such spaces as “former contact zones.”Footnote 7 Instead, inhabitants reshaped contact with German native speakers to suit their own ends. Listening to Western radio did not constitute a failure to recognize the Czechoslovak state's sovereign borders. Rather, foreign radio listening diversified the ways in which Czech and Slovak citizens could position themselves within their own society. Their use of foreign media was ultimately appropriable by Czechoslovak state actors through initiatives such as Alle Neune, and in this way came to impact centralized media programming.

The majority of scholarship on light entertainment's importance during the Cold War focuses on television.Footnote 8 This exploration of German-language radio reveals how governments and media professionals, East and West, placed such hopes in radio too and, moreover, at an earlier period than TV-centered scholarship might suggest. The image that emerges is of a reactive and populist Czechoslovak communist regime seeking and only partially managing during Stalinism and post-Stalinism to cater to the radio preferences of its citizens. Where possible, I introduce the perspectives of listeners themselves into discussions of light entertainment, indicating how game shows, phone-ins and Austrian pop provided opportunities for audience interaction and the possibility of inclusion in Cold War listening communities that hinged more upon musical taste than one's stance toward the Communist Party. The inclusion of listeners’ opinions tempers Reinhold Wagnleitner's findings that Austrian radio helped establish American influence in postwar Europe: in interviews, Czechoslovak listeners repeatedly remarked upon the “Austrian flavor” of what they heard while remaining silent about the Americanizing elements of broadcasts such as advertisements and news.Footnote 9 Rather than separating listeners out primarily by citizenship or ethnicity, I ultimately show how the solidarities fostered by shows such as Autofahrer unterwegs and Alle Neune cut across national boundaries and divided people by generation, geography, class, and technical dexterity.

An analysis of German-language radio reframes discussions of radio listening in Cold War Czechoslovakia, which have largely been shaped by historiography on the American-sponsored broadcaster RFE. Authors have adopted one of four strategies to justify this focus, each with its own drawbacks. First, scholars have worked outward from RFE's articulated aims to understand the station's “success”—and indeed listeners’ behavior. According to Arch Puddington, RFE sought to topple communism through eliciting “acts of personal resistance” from listeners.Footnote 10 Did they or did they not do as the broadcaster hoped? The framing of this question necessarily leads to the conclusion that RFE enjoyed some measure of success (the debate becomes to what degree). But such analysis presumes a rather two-dimensional relationship between broadcasters and listeners, with the former telling the latter what to do, and the latter doing it (or not).

Second, historians have pointed to RFE's unique “popularity.”Footnote 11 But such claims are directly contradicted by Prokop Tomek who finds, in his comprehensive study of the broadcaster, that “the majority of the Czechoslovak population did not listen to Radio Free Europe, nor was it the most popular foreign radio station” in socialist Czechoslovakia.Footnote 12 Tomek belongs to the third school, which explores measures the regime took against RFE to reveal the station's importance.Footnote 13 By positing RFE's social significance as a corollary of regime repression, however, Tomek employs a heuristic framework established by a regime he criticizes for its overreaction and out-of-touch nature to comprehend the society it claimed to represent.Footnote 14 The fourth and final strategy is to cite dissidents from the region saying how important the station was to them.Footnote 15 No one experience of communism—dissident or otherwise—is, of course, more valid than another.Footnote 16 But there is a problem in taking the view of, say, Václav Havel, whose plight was regularly promoted by RFE precisely on account of his dissident status, to speak for Czechs and Slovaks in general (particularly in the face of data suggesting that, when it came to matters of the radio, he does not).

RFE analysts during the Cold War, and subsequent historians of the institution such as Puddington, Parta, and Johnson, equated listening to RFE—and indeed Western radio more generally—with “resistance to communism.”Footnote 17 Despite some fine scholarship nuancing this view, this interpretation has become more widespread in recent years on the part of listeners themselves, with memoirist Jan Šesták claiming, in one example, that listening to radio-relayed rock'n’roll constituted anti-communist “rebellion” in Czechoslovakia.Footnote 18 A recent Prague exhibit suggested that listening to Western radio during the socialist period contributed to Czechoslovakia's “freedom” from dictatorship.Footnote 19 Retroactively understanding foreign radio listening as innately anti-communist fits in to what oral historian Miroslav Vaněk has called a year-on-year growth in “the number of alleged resistors or ‘warriors against the regime’” to have opposed communism after its demise.Footnote 20 Claims such as Šesták's overstate the risks of listening to foreign radio and reduce the politics of this activity to a question of party politics. Ironically, the reconstruction of a communist/anti-communist listening binary revives the logic of communist functionaries during the Stalinist era, who sought to corral radio listening practices into narrow categories of political reliability and unreliability.Footnote 21 Such a party-political understanding overwrites the practical and personal reasons that people tuned into the West.

Here, I use RFE sources to tell another story. The interviews that RFE analysts gathered with emigrants and tourists in the West throughout the 1950s and 1960s provide unparalleled insight into Czechs’ and Slovaks’ listening techniques and attitudes toward radio. By taking their institutional biases into account when reading and rereading such sources, I reveal what they have to say about the enduring significance of the German-language, cross-border connections and light entertainment in communist Czechoslovakia instead.Footnote 22 Although RFE compiled “information items” to look for resistance to communism and find signs of socialism's imminent downfall (and the station's role in this), their findings shed much more light on the cohesive effects of Czechs’ and Slovaks’ wide-ranging and esoteric media tastes in the 1950s and 1960s.

Listening to German-Language Radio in Czechoslovakia

The practice of German-language radio listening in Czechoslovakia had precedents that predated the Cold War. Czech and Slovak listeners were used to hearing German on Czechoslovak frequencies both before and during the Second World War.Footnote 23 They were also used to actively seeking out German-language spoken films: Petr Szczepanik finds that German and Austrian “talkies” beat their Hollywood counterparts hands down in the box office in 1930s Czechoslovakia. He attributes this to the fact that, despite the state's changing geopolitical and technological circumstances, “audiences remained embedded in old cultural traditions of popular music and theatre” established under the Habsburg monarchy, when Vienna was the cultural center of the empire.Footnote 24

Official German-language broadcasting in Czechoslovakia came to an abrupt halt following the end of the Second World War. Banishing German from the corridors of public service broadcaster Czechoslovak Radio, however, did not erase the sound of German from the republic's radio receivers. In the immediate postwar years, the Czechoslovak Ministry of Information acknowledged that it was easier to tune into German-language stations in some western and southern regions of Czechoslovakia than it was to pick up Czechoslovak Radio.Footnote 25 The reception of German-language radio stations became a matter of international diplomacy when Ministry of Information officials urged their counterparts in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to include a clause on radio broadcasting in the postwar peace treaty they were negotiating with Germany; Prague sought to limit German broadcasting aimed at Czechoslovakia, which it understood as an enduring act of hostility on its neighbor's part.Footnote 26

The efforts of the authorities failed to curb the reception of German-language radio on Czechoslovak soil. When those deemed ethnically German (and not sufficiently antifascist) were being stripped of their citizenship between 1945 and 1947, disgruntled Czechoslovak nationalists complained to the Ministry of Information about the continued presence of the German language in Czechoslovakia over the airwaves. According to such activists, Czechoslovakia's aural environment should be purged of German just as its physical environment was being cleared of Germans.Footnote 27 To solve the “problem” of German-language radio, the government set to work building radio infrastructure in Czechoslovakia's border regions and attempting to roll out FM broadcasting (which suffered less interference from neighboring stations). Financial constraints, however, limited the speed of such infrastructural projects’ implementation. Despite the Ministry of Information's wish to achieve complete “radiofication” of Czechoslovakia in the years immediately following the war, this plan remained unfulfilled at the time of the communist takeover of the state in 1948 and indeed for years beyond.Footnote 28

Czechs and Slovaks made the Ministry of Information aware of their own German-language radio listening to gain concessions from officials. In one example, a listener lamented shortly after the communist takeover that “I am always somewhat ashamed when I catch a foreign station, for example Vienna or Budapest, and I hear lots of beautiful arias from our operas, while here amateur brass music prevails.”Footnote 29 In this complaint, the listener couched her habits in the necessary language of shame and regret in a bid to alter Czechoslovak Radio's music policy. She suggested that her foreign listening practices were, in fact, patriotic, as both Vienna and Budapest played “our” operas, while Czechoslovak Radio allegedly shunned them in favor of oompah hits. Other listeners wrote to the ministry outlining their foreign radio-listening habits in a bid to inspire an earlier start to Czechoslovak Radio's morning programming, and a more “natural” style of reporting, such as one heard “in the West.”Footnote 30

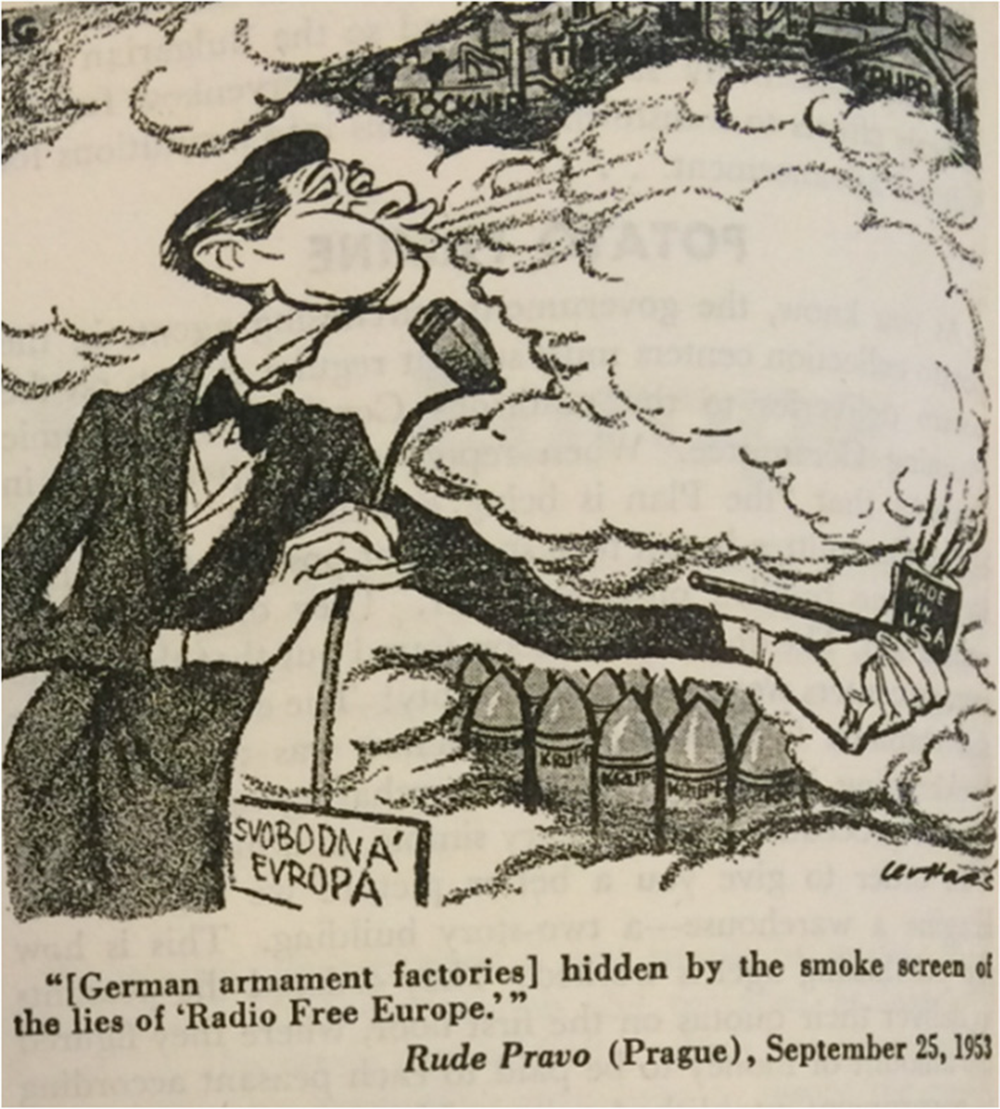

The Czechoslovak government considered outlawing foreign radio listening but decided against such an idea because prohibitive legislation had been highly unpopular under Nazi rule and had also proved almost impossible to implement.Footnote 31 Despite what might be argued from certain historical perspectives, the fledgling socialist regime was in no rush to have parallels drawn between itself and its Nazi forebears. Nor did it seek to expose its inability to monitor and control its citizens by imposing a law that would prove so easy to flout. Instead, the regime sought to nudge Czechoslovak citizens toward approved forms of domestic radio listening and to stigmatize unapproved forms of radio listening socially by dubbing them “German”—regardless of the language such stations broadcast in (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Cartoon from Rudé Právo (“Red Right,” the Communist Party's daily newspaper in Czechoslovakia) in which Radio Free Europe's links to West German rearmament were insinuated. The cleanly shaven, smoke-blowing reporter resembles RFE Czechoslovak service chief Ferdinand Peroutka. The caption was originally in Czech but has been translated into English by the Radio Free Europe analysts who reproduced it. Cartoon reproduced in News from Behind the Iron Curtain 2, no. 11 (November 1953): 48.

With RFE's first broadcasts in 1950, the grudging acceptance of Czechs’ and Slovaks’ foreign radio listening changed. To counter this station's Czech- and Slovak-language broadcasts, authorities placed their faith in the speedy development of new media; television broadcasts, Ministry of Information officials judged (in hindsight rather optimistically), “cannot be adopted from abroad, [and therefore] we want to focus listeners’ interest on television and thus distract their attention from listening to foreign [radio] propaganda.”Footnote 32 Again placing their faith in technology as a solution to the foreign radio predicament, the Czechoslovak authorities introduced jamming in 1952. Jamming was a means of interrupting foreign radio stations by broadcasting domestic programming, or simply a steady signal, on the same frequencies. This drowned out the sound of the stations targeted.Footnote 33 The phenomenon was known colloquially as “Stalin's bagpipes.”

People came up with their own ways around signal jamming, as RFE sources suggest. One Czech surgeon suggested that the practice sent people hunting for foreign stations that may not have been their first choice.Footnote 34 He explained that friends had devised a workaround, which relied upon their foreign language skills: with “transmissions of all the Western broadcasting stations … jammed for listeners in Prague,” the surgeon's acquaintances tuned in instead to “BBC transmissions in German [that] had clear reception.”Footnote 35 Another interviewee described himself habitually undertaking this very practice, calling himself “an enthusiastic listener to BBC programs, but mainly to those of the German service, from about 20:00 hrs onwards.”Footnote 36 This listener followed German-language radio “for two reasons: firstly, it was not jammed, and secondly, he did not want his nine-year-old son to know what he was listening to.”Footnote 37 This testimony shows how Czechs and Slovaks developed techniques to mitigate jamming's effects, relying upon their linguistic skills to produce a DIY solution to the problem jamming posed (with some generations more capable of this than others, to which the father of a nine-year-old fluent in Russian but not German could attest).

Czechoslovakia's Stalinist authorities, and the RFE analysts who quizzed central European listeners, may have wished to present radio listening as an either/or practice: either one listened to “seditious”/“freedom-bearing” foreign broadcasters or one listened to “truthful”/“propagandistic” domestic Czechoslovak Radio. But both constituencies understood very well that listeners in fact station hopped. In the early 1950s, indeed, a range of programs sought to cater to such inconsistent listeners. On RFE, Rub a líc (The Other Side of the Coin) set out to “overturn” the lies that listeners were assumed to have heard first on Czechoslovak Radio, while Czechoslovak Radio meanwhile broadcast numerous commentaries about why the claims made on Radio Free Europe were wrong.Footnote 38 Such mud-slinging over the radio mistook elites’ chief rivals for the foreign radio that actually mattered most to Czech and Slovak listeners.

In 1955, the CIA judged that “listening to Western stations is widespread, and even Party members admit that they have listened to some Western broadcasts.”Footnote 39 The report continued that “intellectuals” listened to “German broadcasts from Switzerland (Beromuenster), RIAS (Berlin), and Red-White-Red (Vienna), whose reception is clearer than [the] Czech and Slovak broadcasts of the Western stations.”Footnote 40 For the CIA, German-language radio listening in Czechoslovakia was a matter of class; professionals were apparently happy to listen to radio in a second language in a way that blue-collar workers were not. The report rejected the premise that foreign radio listening constituted “resistance” to communism, with listening habits cutting across party political affiliation. It also acknowledged that listening ease constituted an important reason why Czechs and Slovaks might tune into such broadcasts.

Jamming was expensive and, in the 1960s, cash-strapped Czechoslovak officials scaled it back. Despite registering a “shift in listenership from Czechoslovak Radio towards more entertaining and topical broadcasts by neutral states’ stations, particularly from Austria and Switzerland,” Politburo members redoubled their efforts to restrict RFE and RFE alone.Footnote 41 They singled it out as the sole foreign broadcaster for jamming, ultimately deploying the practice against only certain shows. Although officials fulminated against German-language media and the unflattering mirror they shone on their Czechoslovak counterparts, they clearly continued to deem such stations less of a personal existential threat. “Entertaining and topical broadcasts” from Austria and Switzerland were much less likely than RFE, after all, to report upon discord and malfeasance within the Czechoslovak Communist Party's ranks.Footnote 42

Meanwhile, RFE listener surveys found that Radio Vienna was the most popular foreign station with listeners in Czechoslovakia throughout the 1960s. The American-sponsored broadcaster instigating such polls was frequently the runner-up. In 1962, 35 percent of interviewees said they listened to Radio Vienna (as opposed to 33 percent who followed RFE). From 1963 to 1964, some 39 percent of Czechs and Slovaks said they tuned into Radio Vienna (as opposed to 37 percent who listened to RFE).Footnote 43 And in 1965, some 71 percent of those questioned said they listened to Radio Vienna (as opposed to 43 percent who listened to RFE).Footnote 44

German-language listening practices then informed how Czechs and Slovaks approached television. During the 1970s, described by Paulina Bren as the start of the television age in Czechoslovakia, German-language programming made its way onto the television sets proliferating in the border regions where German-language radio listening had long been widespread.Footnote 45 Informed by their experiences of radio jamming, Prague officials also decided not to jam these signals, reasoning that such a (costly) step may have interfered in domestic Austrian or West German broadcasting and therefore caused an international dispute.Footnote 46 With a now customary mix of anxiety and impotence, functionaries worried that satellite television would extend coverage to other parts of the country too, addressing citizens hitherto unaware of German-language media's attractions.Footnote 47 That those able to tune into Western television did so is indicated by the high sales of Austrian communist newspaper Volksstimme in Czechoslovakia. In addition to its ostensibly high-quality reporting, more importantly the publication included the daily Austrian television schedule. By the end of the 1980s, the Czechoslovak press resorted to publishing Austrian television listings themselves.Footnote 48

German in Postwar Czechoslovakia

Noting what he calls Radio Vienna's “surprising” popularity in RFE listener polls, which endured through the 1970s and 1980s, Prokop Tomek explains that “only a third of Czechoslovak adults, in particular those in older age groups, understood German.”Footnote 49 What Tomek refers to as “only” a sliver of the population amounted to, by this calculation, more than 3 million people. Older generations were used to German in the classroom, in the media, on street signs and in public institutions, and some may have even participated in a Kinderaustausch (child swap) with a German-speaking family during their childhood. Following the war, the public use of German was restricted, and the venues for speaking and hearing the language reduced. Before German-language television rose to prominence in the 1970s, even members of the state's remaining German minority struggled to “preserve” their German, according to Sandra Kreisslová and Niklas Perzi.Footnote 50

But even during Stalinism, when restrictions ushered in following the war remained strong, official attitudes toward the German language were ambivalent. German allegedly benefited from a shift away from English teaching in Czechoslovak schools in 1951.Footnote 51 Aufbau und Frieden, a German-language weekly newspaper, began publication in Prague that year, renaming itself Volkszeitung in 1966.Footnote 52 It appeared at Czechoslovak newsstands alongside the East German daily Neues Deutschland.Footnote 53 A “general relaxation in language practice” was discernable to an inhabitant of Dolní Poustevna on the border with East Germany by 1952, with German increasingly to be heard on the town's dance floors and in pubs.Footnote 54 German, after all, was a language spoken by citizens of one of Czechoslovakia's socialist allies just meters down the road. German-language training was furthermore required in order to collaborate with East German experts posted to key Czechoslovak industries such as textiles and metallurgy, and indeed on exchanges overseas.Footnote 55

Czechoslovak citizens might listen to the radio to learn German or, conversely, they might learn German to listen to the radio. Domestic broadcaster Czechoslovak Radio promoted the first of these two activities with German-language classes as part of its daytime Školský rozhlas (school radio).Footnote 56 Citizens taught themselves languages directly through listening to foreign stations too.Footnote 57 Others learned foreign languages to better enjoy radio content: the DJs of Radio Luxembourg were Jan Šesták's “secret teachers” of English, which he sought to learn to understand rock'n’roll.Footnote 58 If American and British music seem the only types capable of seducing Czechs and Slovaks into language learning, then the case of erstwhile king of Czechoslovak pop (and Austrian Eurovision star) Karel Gott is revealing. He claimed that West German music provided him with the initial impulse to learn German.Footnote 59

In a state that dedicated limited resources to the instruction of foreign languages, radio could provide a readily available learning aid. Czechs and Slovaks used the medium to improve their German, English and, less well remembered, to gain practice in the mostly widely taught foreign language of all: Russian.Footnote 60 That radio listeners such as Šesták used the medium to work on a language they were being taught in school qualifies the extent to which we should understand such radio usage to constitute “linguistic disobedience.” But decoding what a beloved singer was saying or using radio to heighten one's chances of acing a class test both certainly subsumed the mass media available in Cold War Czechoslovakia to one's personal interests and ambitions.

Radio in the Provinces

Although many of the sources evaluated so far bear a pragocentric bias, Ministry of Information files and Czechs’ and Slovaks’ own testimony of Cold War radio listening (not to mention the experience of driving about the Czech and Slovak Republics today) show that borderlands were the key sites of foreign radio “spillover,” where foreign radio listening was the most commonplace.Footnote 61 Focusing on how local inhabitants actively remediated earlier connections they had had with their neighbors qualifies the extent to which we should view Czechoslovakia's “cleansed” border regions as “former contact zones,” now “hobbled by decaying infrastructure.”Footnote 62 It was in these “peripheral” locations, at times overlooked by elites in Prague's ministries and media historians more generally, that radio listeners used the infrastructures available to them to renegotiate contact with their German-speaking neighbors in ways that benefited them practically and in ways that came to inflect centralized Czechoslovak media content.

The Ministry of Defense's jamming maps for RFE reveal that the state's jamming power concentrated on areas of the country with the highest population density, leaving the state's periphery (where foreign signals were the strongest and the population frequently the most dispersed) relatively untouched (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Map displaying the reach of RFE jamming in Czechoslovakia, September 1952. The red areas are described as being “fully covered, enemy broadcasting does not penetrate at all.” The green areas (which include vast swaths of Czechoslovakia's border regions) are deemed to be “partially covered, sibilants or some words are audible, but impossible to understand the sense of a sentence.” Finally, the blue zones are “uncovered, out of the reach of jamming, everything comprehensible.” It is worth stressing that this map shows only the locations in which RFE was jammed, whereas the picture looked different (and less restrictive) for other Western stations. České Budějovice—later home to the broadcast of Alle Neune—is in a region in which RFE was successfully blocked. Here in South Bohemia, foreign stations transmitted from neighboring Austria were the easiest to catch. Map taken from Barta “Přestaňte okamžitě rušit modré,” 46.

For metropolitan visitors, the sonic experience of this map meant a holiday for the ears. Jan Šestak recalls how a trip to the North Bohemian mountains gave his hearing a break: upon return to Brno, his attempts to tune into Western radio were again marked by “music covered in static, music that would fade depending on the atmospherics.”Footnote 63 And just as one might come to associate a particular song with one's summer holiday today, RFE sources suggest that listening to foreign radio stations was seen by some city dwellers as part of, and subsequently synonymous with, the experience of vacations spent out of town.Footnote 64

For local border region inhabitants, Western media reception was widespread enough that it created its own social allegiances and social divides. A Sudeten German from North Bohemia suggested that the RIAS signal was so clear in Jablonec nad Nisou that local German and Czech speakers alike tuned in to the station. While he petitioned RIAS to schedule more programming specifically for ethnic Germans living as minorities in socialist states (as he believed Czechs and Slovaks already had their own station—RFE—for this purpose), he nevertheless identified the shared experience of listening to RIAS as something diminishing differences between Jablonec's linguistic groups.Footnote 65 Shows such as Schlager der Woche may have brought people together, in his opinion, but they were also capable of driving neighbors apart. In České Budějovice's school yards some years after the end of radio's second golden age, Martin Matiska recalled that Austrian radio continued to confer a social prestige on its teenage listeners, stigmatizing those who failed to listen. Matiska explained that the Austrian pop chart broadcast weekly throughout the 1980s on Ö3 on Sundays, and those who missed it were subsequently pilloried for their lack of street cred in school on Mondays.Footnote 66 His listening habits and those of his peers explain the popularity of stars like Falco and Sandra in 1980s Czechoslovakia, and their prominence on nostalgic radio stations playing classic hits in the Czech Republic today.Footnote 67

Czechoslovak functionaries acknowledged the state's periphery as a site where “listening to West German radio and in particular the American station RIAS was widespread” throughout the 1960s. They understood these sites as key venues of Austrian and Swiss radio listening too.Footnote 68 It was such official recognition that paved the way for state-sanctioned cross-border initiatives like Alle Neune in 1965.

If radio in the provinces is a geographic term denoting listening habits in the Czechoslovak territories with the strongest Western radio frequencies, then it is also a generic term referring to a particular type of radio broadcasting. Austrian radio directors, for example, distinguished between metropolitan and provincial audiences when they fashioned the country's radio network into the statewide ORF in the mid-1950s.Footnote 69 With the restructuring of Austrian radio following the signing of the State Treaty, Vienna became a statewide broadcaster tasked with burnishing the image of Austria as a “cultural superpower” domestically and to audiences abroad, while regional stations such as that based in Linz—producers of the aforementioned Alle Neune—were expected to broadcast more light entertainment, including game shows and popular music. Thus, less sophisticated regional offerings came to be broadcast on Ö2's frequencies, and Vienna was eventually rebranded as Ö1. Provincial radio was qualitatively and aesthetically different from that produced in the media capital, and letters to Czech officials about Vienna's arias aside, it appears to have been this light entertainment that proved a particular hit with Czechoslovak listeners. This point is made by and simultaneously obscured in the surveys used here, which bundled different Austrian stations together, asking their respondents to discuss their experiences of listening to “Vienna.”Footnote 70

Faced with the reality of large audiences at the peripheries of central and eastern European states, Western media programmers yearned above all to address metropolitan elites.Footnote 71 A well-remembered example of these attempts is provided by the Stadtgespräche (city talks)—a Czechoslovak Television and ORF coproduction spanning 1963–1964. This short-lived set of TV discussions derived their weight from the “media capital” of their broadcast locations, Prague and Vienna. Invited guests discussed human rights and cultural politics, among other topics. Their host, Helmut Zilk, subsequently became the mayor of Vienna and modestly suggested in hindsight that the programs had served as the catalyst for the Prague Spring.Footnote 72

Such debates about human rights and cultural politics were not, however, to everyone's taste. For television, Paulina Bren has claimed that the “majority of viewers who could turn to Western television did not do so for purely ideological reasons.” Instead, they switched when programs were “too strongly adapted to the demands of the Prague intellectual elite” (imagine their dismay on the nights of the Stadtgespräche!).Footnote 73 Rightly or wrongly, media professionals and pollsters East and West came to think along the lines of two audience camps whose entertainment preferences suggested they had more in common with audiences across borders than with fellow nationals. With some scholarly attention already paid to the metropolitan elites embodied by Zilk and the Stadtgespräche, I turn now to his colleagues at “Ö-Regional”—Walter Neisner and Rosemarie Isopp—and the mix of Austrian traffic news and music requests they presented in Autofahrer unterwegs.Footnote 74

Autofahrer Unterwegs

When trying to understand Austrian radio's “evident popularity” in the mid-1960s, RFE staff attributed it “first and foremost” to “the popular daily 50-minute program Autofahrer unterwegs.”Footnote 75 Explaining that “traditional ties between Austria and the populations of Southern Bohemia, Southern Moravia, and South-West Slovakia” played an important role in Austrian radio's approval ratings, RFE analysts dismissed their findings that more Czechs and Slovaks tuned into Austrian radio than their own reporting as a historical relic. Such behavior, in this view, had more in common with the world of the Linz-České Budějovice horse-drawn railway than it did with the new, Cold War world order in which these listeners found themselves.

But program format, evaluators conceded, was a crucial factor in attracting audiences at home and abroad. They concluded that Autofahrer unterwegs’ combination of “advice to the motorist,” “human interest items,” and “personal greetings and messages from drivers … sent to persons in Austria and other countries, including Czechoslovakia” proved singularly successful.Footnote 76

Hosted by Niesner and Isopp, Autofahrer unterwegs broadcast traffic updates and details of stolen cars alongside messages to drivers daily from 1957. The show served as a message board for matters not directly related to driving as well. It epitomized the “immense popularity of local classifieds” that Frank Bösch and Cristoph Classen suggest swept 1960s central Europe, creating an audio version of the free newspapers full of such advertisements that proliferated in the West at this time.Footnote 77 The tremendously popular show spurred its own eponymous polka and, in 1961, a film (Figure 3).Footnote 78 It ceased broadcasting after an impressive forty-two-year run in 1999.

Fig. 3. Autofahrer unterwegs film poster from 1961.

In 2017, Isopp recalled that “everything was possible with this program … When someone had an accident and needed a wheelchair, we had one by the next day. We brought children who had run away home. And we found an antidote for a child who had been bitten by a snake and saved his life.”Footnote 79 The sort of classified advertising service that Autofahrer unterwegs ran extended into Czechoslovakia, with Isopp recalling:

A woman from Bratislava called us crying during a broadcast. She begged for help, because she had had an eye operation and feared that she would go blind as she was running out of medicine. I announced this and a quarter of an hour later a pharmacist came along with medicine. But how to get this across the Iron Curtain? A member of the public stood up and said, “My name is Schnitzel, and I have a visa and can go there!” He left the recording studio to thunderous applause. Two days later the women called in crying again. Her sight had been saved.Footnote 80

Isopp's narration sounds dramatic, but Schnitzel's journey “across the Iron Curtain” was far from isolated during Autofahrer unterwegs’ heyday. Hundreds of Czechs, Slovaks, and Austrians traversed the border legally for work or family reasons already in the 1950s.Footnote 81 The following decade, tourism in both directions further increased, with Czechs and Slovaks now visiting Austria en masse to see the sights.Footnote 82 Sport was another long-running area of contact among Czechs, Slovaks, and their German-speaking neighbors.Footnote 83 By the 1960s, football matches between inhabitants of the Czech and Austrian side of the border were even becoming an annual fixture.Footnote 84 And material goods such as newspapers, books, and clothing made their way across the border alongside the eye medicine that Schnitzel transported—although the flow of “finished” goods was stronger in one direction than the other.Footnote 85

Isopp's recollections are inflected with a tinge of messianic Western humanitarianism, but she nevertheless places the story of the woman in Bratislava within a larger context of real personal connection and ad hoc aid fostered by the show. Although RFE dismissed Austrian radio listening as a historic relic, Isopp's statement in fact shows how Czechs and Slovaks used new media (such as FM broadcasting, telephones, and personal cars) in savvy ways to overwrite earlier historic connections between Austria and their state. Autofahrer unterwegs suggested a cross-border community of those ready to help and be helped, and a conversation that acknowledged Czechs’ and Slovaks’ material circumstances and difficulties (which is not to say that Czechs and Slovaks were “victims” of an underdeveloped consumer market, but rather that the very present grumblings about material shortages audible in Czechoslovakia at this time found international amplification through Autofahrer unterwegs).

Light Entertainment's Value during the Cold War

Alongside Autofahrer unterwegs, RFE cited the music played by Austrian radio and game shows like Alle Neune as key to Austrian radio's success.Footnote 86

Austrian broadcasters had sought to “position [their country] with light classical music” through international broadcasts as early as the interwar period, claims Suzanne Lommers.Footnote 87 They continued with this strategy throughout the 1950s in explicit distinction to purveyors of jazz, like American Forces Network, and alleged purveyors of “amateur brass music,” Czechoslovak Radio.Footnote 88 Vienna aired some two hundred hours of music a month by the 1950s, including “weekly concerts of the Vienna Philharmonic held in the Konzerthalle.”Footnote 89 In a subtle bid to normalize American-style radio advertising, such concerts were sponsored, claims Reinhold Wagnleitner.Footnote 90 Perhaps this was so, but in the ears of the US officials overseeing them, the Austrian radio journalists preparing them, and the Czech and Slovak listeners quizzed about them, the weekly recitals became associated with an “Austrian flavor”—much more so than their subtle capitalist framework.Footnote 91 This association was perhaps shaped by enduring ideas of what Austria sounded like cultivated by radio professionals of an earlier age.

Red-White-Red (RWR—ORF's predecessor broadcasting from the American zone of Austria until 1955) placed great importance upon the quantity and quality of music it broadcast to attract listeners to its news.Footnote 92 But it is not clear from listener testimony that it succeeded. Czech and Slovak interviewees singled out the music they had heard on Austrian frequencies to the exclusion of all else. An interviewee from South Moravia suggested, representatively, that RWR was “the most reliable station when one wanted to listen to good music.”Footnote 93 In fact, Czechoslovak Radio broadcast “good music” too, but not reliably so: a barber from nearby explained that listening to domestic radio required “planning … so one does not tune in by mistake to some speech or The Radio University. One reads magazines to find out when a symphony orchestra or chamber music will be on. It is the only agreeable and unobjectionable listening possible.…”Footnote 94 Listening to music constituted relaxation to the barber, who contrasted this with the experience of following political speeches or overtly edifying programming. Interviews with RFE pollsters suggest that RWR's Czech and Slovak listeners may have been just as discerning in their preferences for music over the spoken word, raising the question of whether some were happy not to understand the nuance—or even all that much—of what they heard. For all their talk of “good music” on RWR, interviewees make no mention of the news accompanying it.Footnote 95

Game shows were another radio format linked to the early days of RWR. They were introduced to Austrian radio on account of their popularity with American audiences and to present Austrians with an image of “good play” according to American rules.Footnote 96 But they also came to be wholeheartedly endorsed by socialist media from around the time of Alle Neune's broadcast in the mid-1960s, explains Christine Evans, as they “performed the state's responsiveness to its citizens” and suggested the importance of citizen participation on “predetermined fields of play.”Footnote 97

Teaming up with regional Austrian radio, Czechoslovak Radio sought, through Alle Neune, to “gatekeep the foreign,” presenting itself as, in fact, the best means to tune into foreign radio.Footnote 98 Alle Neune did little to “mobilize citizens towards the construction of socialism,” which is what socialist game shows, according to Evans, set out to do.Footnote 99 It was instigated by ORF and followed a format that the creators had devised for earlier, intra-Austrian broadcasts. But the cooperation was no trojan horse for Austrian-style social democracy—it had several important benefits for Czechoslovak Radio and Prague officials too. It presented Czechoslovakia and Austria as technological equals capable of such broadcasting feats on account of both states’ robust radio infrastructures. Furthermore, by introducing Austrian-style light entertainment into Czechoslovak radio schedules, Alle Neune facilitated the ongoing appropriation of radio genres familiar from the West onto Czechoslovak frequencies.Footnote 100

Thus, Alle Neune served the political purposes of Czechoslovak radio professionals and officials. But what about its listeners? Writing in to claim a free booklet, or to Autofahrer unterwegs for a shout-out, was certainly not party political, but it was political in the sense that Michel de Certeau would understand it—in that it saw nonelites use mass media to their own specific ends. Procuring eye medicine or swatting up on the pop charts in order to impress one's peers in the schoolyard on Monday are but two ways that consumers of mass media can “make use of the strong.”Footnote 101 To me, this represents the interesting ways that people actually go about incorporating mass media into their everyday lives, tailoring such media to their own ends.Footnote 102

Programs such as Alle Neune, Autofahrer unterwegs, and the Austrian pop chart reveal the different and varied roles that radio can play for its listeners. RFE sought to furnish its audiences primarily with news, whereas the Austrian radio shows examined here set out to provide entertainment.Footnote 103 Correspondingly, Czechs and Slovaks did not turn to Austrian radio just because they were unable to tune into RFE. Instead, game shows, phone-ins, and Austrian pop provided different opportunities for audience interaction and the possibility of participation in different listening communities. The same listener could and did, of course, seek out news and entertainment in turns, but it was RFE analysts’ nagging concern that the latter held more importance than their own offerings for Czechs and Slovaks (in terms of time spent listening, memorability, audience participation, and affection). This article has explored why, concretely, their concerns might have been justified.

Conclusion

The director of ORF, Gerd Bacher, ruminated in 1967 that “for those with whom we lived for centuries in the same state, we [meaning Austrians] are, quite simply, ‘the West.’”Footnote 104 It was a question of personal framing whether Czechs and Slovaks did indeed tune into German-language radio because they believed it represented “the West.” Beyond debate is that central Europeans entered the Cold War with their own radio traditions and understandings of media, which continued to develop over the decades that followed. Although RFE may have been the ultimate foreign radio reference point for communist politicians such as Information Minister Václav Kopecký, many Czech and Slovak citizens did not agree. This article has explored how, over the twentieth century, as Heidi Tworek argues, “many individuals, groups, and states challenged Anglo-American infrastructures, firms, and approaches to news”—and indeed their centrality to regional media environments.Footnote 105

This article has disputed the particularity of the two Germanies’ Cold War media history, arguing that cross-border German-language radio also mattered profoundly in central Europe, where listening habits were shaped by the region's multilingual heritage. Surprisingly perhaps (and the teenagers of České Budějovice notwithstanding), older generations might be said to have proved more ingenious in their use of available media. Just as Petr Szczepanik finds that cultural affinities with Austria survived geopolitical and technological shifts well into the 1930s, I have proposed that such affinities lasted even longer and that the “cultural barriers” evoked by Bösch and Classen were not yet thoroughly entrenched until deep into the Cold War—indeed the extent to which they are in place today is still open to question.Footnote 106 Analyzing German-language radio listening in Czechoslovakia has additionally shed light on the enduring importance of German as a language of regional communication, the continuing importance of cross-border connections, and the significance of light entertainment for central European audiences during the Cold War.

Alle Neune officialized practices of which the Czechoslovak and Austrian authorities had been long aware—cultivated by shows such as Autofahrer unterwegs. Rather than constituting the legacy of a bygone, Habsburg age, German-language radio listening saw Czechs and Slovaks use new technologies in sophisticated ways to overwrite and alter earlier connections between their state and their nearest neighbors. The Cold War certainly shaped the choices that Czech and Slovak listeners had available to them (in terms of what was jammed and which languages they knew), but it may not have shaped their approach to the German-language radio they heard. An altogether recognizable mix of self-improvement, longing for connection, peer pressure, habit, curiosity, a desire to vent one's grievances, and material aspiration appeared to inflect Czechoslovak listeners’ preference for Austrian and West German radio during the Cold War—and we should not collapse this into the easy catchall of “resistance to communism,” as some period RFE analysts and several recent memoirs and exhibits have done. Finally, I have indicated how the solidarities that German-language radio listening forged divided listeners not by citizenship or ethnicity, which is often how media consumption in twentieth-century central and eastern Europe is framed, but by age, technological know-how, class, and geography instead. In contradistinction to the well-studied divide between East and West Berlin, Yuliya Komska has called the West German–Czechoslovak border “the Cold War's quiet border.”Footnote 107 It turns out that it was anything but.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Jannis Panagiotidis, Philipp Ther, Dean Vuletic, and Stephanie Weismann at the University of Vienna's Research Center for the History of Transformations (RECET) for providing feedback on drafts of this text. Thank you also to participants of a 2019 German Studies Association panel on “Listening to Germany and Austria”—in particular discussant Kira Thurman—for their comments. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers whose constructive feedback proved a tremendous help when improving this article. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 847693.