Introduction

The Near East is the cradle of sheep domestication. Since the ninth millennium BC, sheep have played a major role in societal development, and have been an important element in many different spheres of human activity (Vigne et al. Reference Vigne, Peters and Helmer2005, Reference Vigne, Gourichon, Helmer, Martin, Peters, Enzel and Bar-Yosef2017). Despite numerous studies on the domestication of a variety of plants and animals using a range of bioarchaeological methods, few have investigated the development of breeding and zootechnical practices by the first herders (e.g. Zeder et al. Reference Zeder, Bradley, Emshwiller and Smith2006; Colledge et al. Reference Colledge, Conolly, Dobney, Manning and Shennan2013; Cucchi et al. Reference Cucchi, Dai, Balasse, Zhao, Gao, Hu, Yuan and Vigne2016; Pöllath et al. Reference Pöllath, Schafberg and Peters2019; Balasse et al. Reference Balasse, Tresset, Obein, Fiorillo and Gandois2019). This is partly due to the difficulty in obtaining evidence of such activities using traditional zooarchaeological methods, for example, in the identification of phenotypical or physiological features transmitted from one generation to the next, and related to a particular domesticated population.

The domestication process resulted in behavioural, functional and anatomical changes in sheep. Due to the ethological and eco-physiological characteristics of this species, it can tolerate a broad range of geo-climatic conditions (Ryder Reference Ryder1983). Both natural and artificial selection have played important roles in producing adaptive traits, resulting in breeds that have been selected for specific climates, available vegetation and resistance to local diseases and parasites (Pilling & Rischkowsky Reference Pilling, Rischkowsky, Rischkowsky and Pilling2007).

Sheep provide diverse food products (meat, fat and milk) and craft materials (hide, fleece, tendons, horn and bone), as well as manure fertiliser. Some products (called secondary products) can be obtained repeatedly throughout the animal's life, such as milk, which has high nutritional value, and wool, a raw material with exceptional properties (Sherratt Reference Sherratt1983).

The origins of sheep breeds: the zooarchaeological and textual clues

Approximately 1000 ovine breeds are present today throughout the world, resulting from a complex history of natural and human selection that has enriched the phenotypic diversity in sheep (Scherf & Pilling Reference Scherf and Pilling2015). The process of breed emergence is still poorly understood, however, particularly regarding the diversity of domestic phenotypes, the role of environmental conditions and zootechnical innovations responsible for the emergence of breeds, as well as the role of secondary products. To address these issues, the EVOSHEEP project—funded by the French National Research Agency—launched in autumn 2018.

Mortality profiles provide the earliest indirect evidence of sheep-milk production, which can be dated to the eighth millennium BC, and fleece production dating to the seventh millennium BC (Helmer et al. Reference Helmer, Gourichon and Vila2007). By the sixth millennium BC in the Near East, an increase in artefacts related to fleece handling, such as spindle whorls, is indicative of textile fibre-processing of both animal and vegetal origin (Rooijakkers Reference Rooijakkers2012).

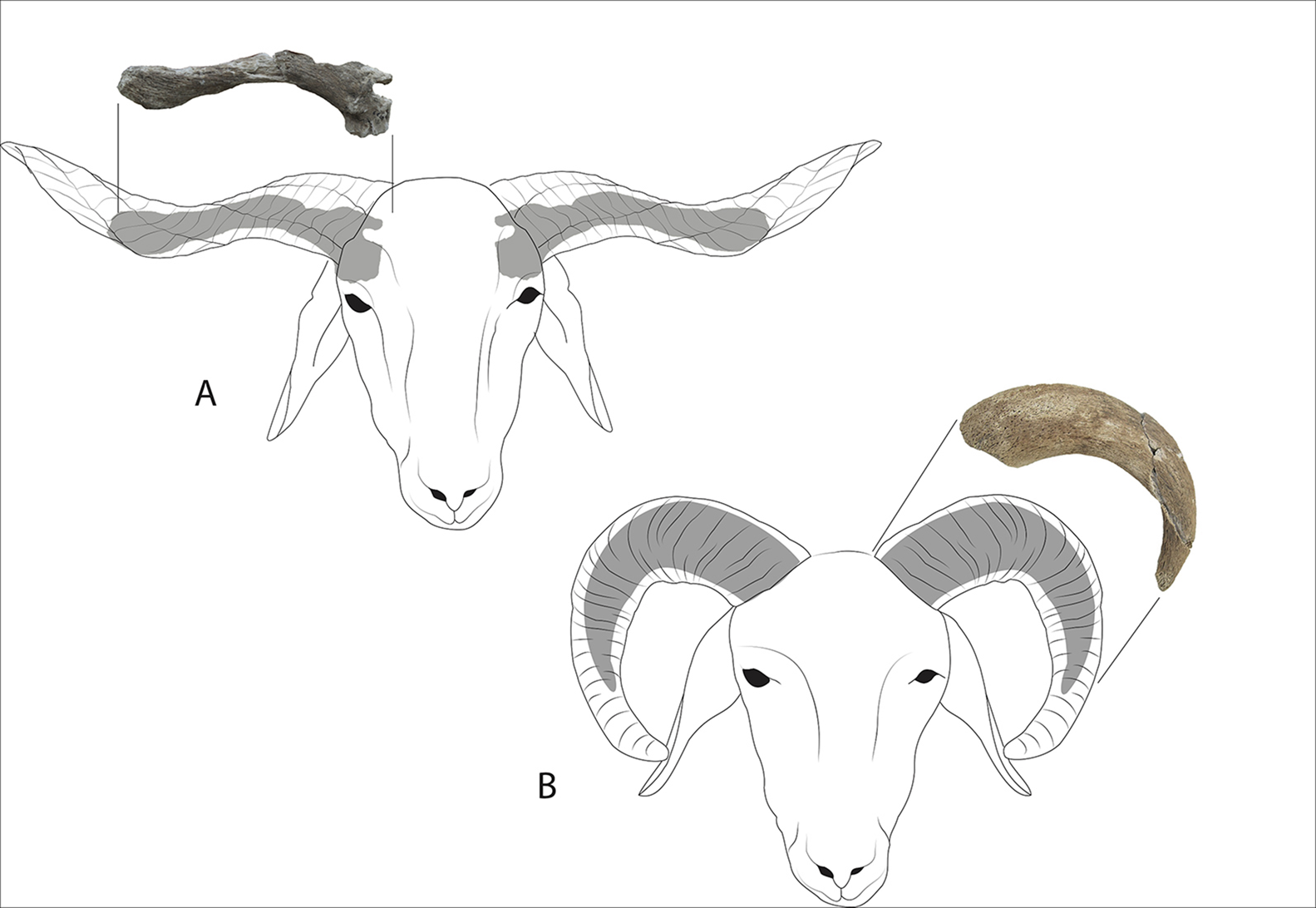

In northern Mesopotamia, an important increase in sheep husbandry during the fourth millennium BC (Uruk period) can be identified (Vila & Chahoud Reference Vila, Chahoud, Gourichon, Daujeard and Brugal2019). Zooarchaeological studies have shown that these animals are larger than earlier sheep (Vila & Helmer Reference Vila, Helmer, Breniquet and Michel2014). Their horns form horizontal spirals, which are similar in shape to those of contemporaneous Levantine and Egyptian sheep (Figure 1a & Figure 2). At the beginning of the third millennium BC (Early Bronze Age), the average sheep size was smaller, and the horns were coiled (Figure 1(b)). Iconographic depictions from this period often show a well-developed woolly coat (Figure 3) (Vila & Helmer Reference Vila, Helmer, Breniquet and Michel2014). Mesopotamian texts mention a diversity of sheep types of various origins as early as the third millennium BC (Figure 4), and later textual descriptions of wool quality and colour in the Near East and Aegean regions also confirm this diversity (Breniquet & Michel Reference Breniquet and Michel2014). One hypothesis, therefore, is that woolly sheep breeds were favoured by urban development and the associated increasing demand for textile production.

Figure 1. A) Horizontal spiral horn core of a Late Chalcolithic sheep (Tell Sheikh Hassan, Syria, Uruk period); B) coiled horn core of an Early Bronze Age sheep (Kharab Sayyar, Syria, third millennium BC) (photographs by E. Vila; drawings by F. Truxa).

Figure 2. Uruk-Warka (Iraq), Uruk period. Lower register: row of sheep; rams with horizontal spiral horns and a mane (detail of Warka Vase, Iraq Museum); available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78821078 (accessed 4 December 2020); CC BY-SA 4.0).

Figure 3. Detail of a seal from Mozan (Syria), third millennium BC: ram with coiled horns and woolly coat (taken from Buccellati & Kelly-Buccellati Reference Buccellati and Kelly-Buccellati1995–1996: fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Tablet in Sumerian (Ur III) that mentions a fat-tailed sheep. Anonymous collection (CDLI P313095; photograph courtesy of B. Englund).

Research questions

EVOSHEEP is a multidisciplinary project combining archaeozoology, geometric morphometrics and genetics to study archaeological sheep assemblages that date from the sixth to the first millennia BC in eastern Africa, the Levant, the Anatolian South Caucasus, the Iranian Plateau and Mesopotamia. In addition, the project incorporates a historical approach based on Sumerian-Akkadian texts and ancient Near Eastern iconography.

The following research topics will be investigated:

1) How did environmental factors and husbandry practices play a role in the biological and physical modifications of sheep compared with their wild ancestors?

2) When and where did major phenotypic characteristics, such as a fat tail, woolly fleece, pigmentation and lack of moulting, appear?

3) Did the herders’ interest in secondary products (e.g. fleece, milk) contribute to the selection of new phenotypic traits?

4) Is there a relationship between regional variation in sheep size and horn-core morphology and the emergence of different varieties or breeds?

5) How did the development of the textile industry during the third millennium BC affect sheep herding and urban development in South-west Asia?

6) Were fleece quality and pigmentation critical factors in the development of the textile industry and dyeing techniques?

To address these issues, EVOSHEEP will perform three-dimensional geometric morphometric analysis of selected bones with discriminating morphological markers (the humerus, astragalus, calcaneus and petrous bone). The genetic approach, based on the study of present-day genetic variation in a large range of breeds and populations, will be used to identify key genomic regions associated with important phenotypic traits (e.g. tail, coat, horns and colour), followed by palaeogenetic analyses of archaeological bones. EVOSHEEP also aims to create an osteological reference collection of present-day sheep breeds from the Middle East (Iran, Lebanon) and Africa (Ethiopia) (Figure 5). An online, open-access database is currently under development on a dedicated website.

Figure 5. Washera breed, Ethiopia (photograph by E. Vila).

Acknowledgements

The project is coordinated by a consortium of five partner laboratories: Laboratoire Archéorient—Environnements et Sociétés de l'Orient Ancien (coordinated by E. Vila); Archéozoologie, Archéobotanique: Sociétés, Pratiques et Environnements (coordinated by M. Mashkour); Anthropobiologie Moléculaire et d'Imagerie de Synthèse (coordinated by L. Orlando); Laboratoire d'Écologie Alpine (coordinated by F. Pompanon); and the Smurfit Institute of Genetics (coordinated by D. Bradley). It also benefits from collaborations with French archaeological missions of the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, other European archaeological expeditions, the General Directorates of Antiquities, as well as academic institutions in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Ethiopia, Lebanon, Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Syria and Turkey.

Funding statement

The EVOSHEEP project is funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR PRC Project: ANR-17-CE27-0004).