Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, HIV is a major cause of adolescent morbidity and mortality. Of the 1.6 million adolescents living with HIV globally, around 1.1 million reside in Eastern and Southern Africa and another 430 000 in West and Central Africa (UNICEF, 2019). Approximately 35 000 adolescents died of HIV in both regions, and nearly 190 000, the majority of them adolescent girls, got newly infected in 2017 (UNICEF, 2018a; 2018b). HIV is associated with adolescent mental health problems in both, high- and low-income settings (Mellins and Malee, Reference Mellins and Malee2013; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, McCoy and Lee2017), with social exclusion and HIV-related stigma playing an important role (Boyes et al., Reference Boyes, Cluver, Meinck, Casale and Newnham2019). Mental health problems among HIV-positive adolescents have been linked to poor adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART) and a higher risk of substance abuse and sexual risk behaviors, leading to less favorable health outcomes and a higher risk of HIV transmission (Mellins and Malee, Reference Mellins and Malee2013; Dow et al., Reference Dow, Turner, Shayo, Mmbaga, Cunningham and O'Donnell2016; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, McCoy and Lee2017).

In the African context, data on adolescent mental health is scarce and capacities for mental health care are limited, as is the case in many low-income settings (Fisher and Cabral de Mello, Reference Fisher and Cabral de Mello2011; Erskine et al., Reference Erskine, Baxter, Patton, Moffitt, Patel, Whiteford and Scott2017; WHO, 2018; UNICEF, 2018c). Regarding the mental health of HIV-positive adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa, numerous studies have been published in recent years (Kamau et al., Reference Kamau, Kuria, Mathai, Atwoli and Kangethe2012; Louw et al., Reference Louw, Ipser, Phillips and Hoare2016; Lwidiko et al., Reference Lwidiko, Kibusi, Nyundo and Mpondo2018; Hoare et al., Reference Hoare, Phillips, Brittain, Myer, Zar and Stein2019; West et al., Reference West, Schwartz, Mudavanhu, Hanrahan, France, Nel, Mutunga, Bernhardt, Bassett and Van Rie2019). To our knowledge, there is no recent review which specifically summarizes epidemiological data from different sub-Saharan settings and reports on the quality of these studies. A recent review by Vreeman et al. (Reference Vreeman, McCoy and Lee2017) included studies from both high-income and low-income settings and included a broad age range (aged < 10 and up to 24). Another review on mental health problems of perinatally infected HIV-positive youth predominantly included studies from the United States (Mellins and Malee, Reference Mellins and Malee2013). With our review, we sought to close this gap by summarizing the existing evidence on the prevalence of mental health problems among HIV-positive adolescents (aged 10–19) in sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, we explored associated sociodemographic, health-related, and community factors, as documented in the included studies.

Methods

This study formed part of an overarching systematic review that explores the prevalence of mental health problems in general adolescent populations in sub-Saharan Africa as well as in risk groups (HIV/AIDS, poverty, or exposure to trauma). The systematic review aims at updating the findings from the review of Cortina et al. (Reference Cortina, Sodha, Fazel and Ramchandani2012) on child mental health in sub-Saharan Africa that included studies up to 2008. It was registered with the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews at the National Institute for Health Research (PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018112853) and will be published in separate subsections. Due to the number of retrieved studies, we decided to publish the results of the systematic review in subsections, with this section focusing on the prevalence of mental health problems specifically among HIV-positive adolescents, who constitute one of our a priori risk groups.

The systematic review was undertaken by the MEGA project team. MEGA is an international collaborative project for mental health promotion among adolescents in South Africa and Zambia (Lahti et al., Reference Lahti, Groen, Mwape, Korhonen, Breet, Chapima, Coetzee, Ellilä, Jansen, Jonker, Jörns-Presentati, Mbanga, Mukwato, Mundenda, Mutagubya, van Rensburg-Bonthuysen, Seedat, Stein, Suliman, Sukwa, Turunen, Valtins, van den Heuvel, Wahila and Grobler2020; MEGA 2020). The project aims to build capacity for adolescent mental health among health care workers in primary care settings by training the trainers in higher education institutions in both countries.

Search strategy

An extensive database search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and PsycINFO in June and November 2018, covering a 10-year period. Additional studies were retrieved from Google Scholar, from reference lists and citations of the included studies or through contact with other researchers. A second search was conducted in January 2020 to include articles that were published since our search in 2018. Only peer-reviewed studies reporting prevalence data and published in English were included.

The COCOPOP scheme was used to define inclusion and exclusion criteria for the database search (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017)

-

− Context: sub-Saharan Africa, defined according to the World Bank Country and Lending Groups (World Bank, n.d.).

-

− Condition: mental health problems or clinical diagnoses, as assessed by standardized questionnaires or diagnostic interviews.

-

− Population: adolescents aged 10–19, residing in sub-Saharan Africa.

Exclusion criteria were:

-

− publications on populations with a broader age range than 10–19 that do not report separate prevalence data for adolescents between 10 and 19;

-

− psychiatric clinical populations (publications on clinical populations from HIV care were included);

-

− lack of prevalence data;

-

− non-standardized or incomplete instruments, not regularly used in mental health research;

-

− reviews, validation studies, or qualitative studies.

The following search terms were used: child*, youth, adolesc*; sub-Saharan, Africa, South Africa, Zambia; prevalence, incidence, epidemiol*; psychiat*, mental, depress*, ADHD, anxiety (see supplementary material, Table 2). The database search revealed 1374 articles. In total, 65 additional articles were found through Google Scholar, further 22 through reference lists, citations, and contact with other researchers. After the removal of duplicates, 1070 records were left for the screening of title and abstract. After exclusion of articles on clinical psychiatric populations or youth beyond the age range of 10–19 and articles with a wrong publication type or date, 301 articles were eligible for full-text assessment.

The exclusion of articles was done according to the PICO-based taxonomy (Edinger and Cohen, Reference Edinger and Cohen2013). All articles were independently evaluated by two researchers. Fourteen articles focusing on the prevalence of mental health problems among HIV-positive adolescents were included in this sub-review (Fig. 1). Six articles regarding HIV-affected adolescents or adolescents from high-prevalence communities (antenatal HIV-prevalence >30%) were included in the second systematic review (to be published separately; see supplementary material, Table 3).

Fig. 1. PRISMA Flow-chart. *65 articles found from Google Scholar, 22 from reference lists, citations or author contact. **found from PubMed (1), PsycINFO (4), Scopus (3), Google Scholar (6), through reference lists (2), recommendation by other researchers (3); four articles were found in more than one source.

Data extraction and analysis

The following scheme was used for data extraction: publication year, land/region, study design, sample origin, sampling method, sample size, distribution males/females, age range, risk factors, instruments, informant, data collection process, prevalence of psychological symptoms or mental disorder, and additional findings. Due to the broad heterogeneity of instruments and cut-offs used to assess mental health problems across studies, a meta-analysis was not performed. Instead, data were analyzed and presented in a descriptive, narrative overview. Results from statistical analyses of associated factors were also included in the analysis. Only factors reaching a significance level of p = 0.05 or less were considered as being significantly associated.

Quality assessment of the studies was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (Munn et al., Reference Munn, Moola, Lisy, Riitano and Tufanaru2015). This was extended to cultural appropriateness (see supplementary material, Table 4).

Results

Fourteen studies from eight different countries were included. All of the studies except one were conducted in Eastern and Southern Africa, most of them in countries with a high burden of the HIV epidemic. Study designs were mainly cross-sectional, there were two case-control studies and one mixed-methods study of which only the quantitative findings are reported here (see supplementary material, Table 4). In eight of the studies, screening scales were used to assess mental health symptoms or behavior (Table 2). Four studies reported a disorder prevalence, assessed by either diagnostic interviews or symptom count score. Two studies (Musisi and Kinyanda, Reference Musisi and Kinyanda2009; Woollett et al., Reference Woollett, Cluver, Bandeira and Brahmbhatt2017) used both. Because Woollett et al., indicated that cut-offs were set to identify symptomatic adolescents and not used for diagnostic purposes, the results are reported in the section on symptom prevalence. Most of the studies assessed point prevalence. Exceptions are marked in Table 4, supplementary material.

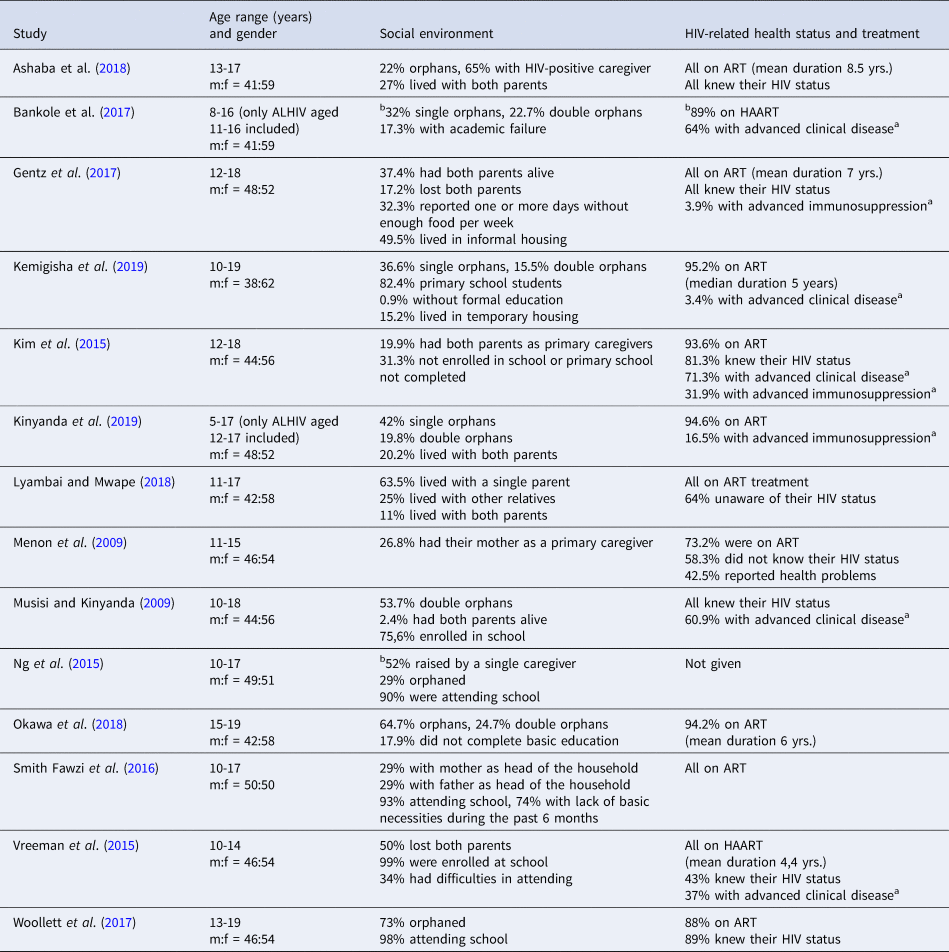

Sample sizes ranged between 82 and 1339 (Table 2). For four of the studies, only a subsample could be included in the review (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Kirk, Kanyanganzi, Fawzi, Sezibera, Shema, Bizimana, Cyamatare and Betancourt2015; Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Bakare, Edet, Igwe, Ewa, Bankole and Olose2017; Kinyanda et al., Reference Kinyanda, Salisbury, Levin, Nakasujja, Mpango, Abbo, Seedat, Araya, Musisi, Gadow and Patel2019). Most samples included older (15–19) and younger (10–14) adolescents. Exceptions were the study by Vreeman et al., and Menon et al., who focused on younger adolescents and Okawa et al., who focused on older adolescents (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, Scanlon, Marete, Mwangi, Inui, McAteer and Nyandiko2015; Okawa et al., Reference Okawa, Kabaghe, Mwiya, Kikuchi, Jimba, Kankasa and Ishikawa2018). Females and males were almost equally distributed, with females being slightly overrepresented (58–62%) in five of the studies. The characteristics of the study samples are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and health-related factors of the study participants

aadvanced immunosuppression = CD4 count < 350/mm3, advanced clinical disease = WHO stage 3 or 4

bapplies to the whole study group

Table 2. Overview of the studies included

ALHIV = adolescents living with HIV

a instrument previously used or validated in other African settings (Chipimo and Fylkesnes, Reference Chipimo and Fylkesnes2010; Chishinga et al., Reference Chishinga, Kinyanda, Weiss, Patel, Ayles and Seedat2011; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Scorza, Meyers-Ohki, Mushashi, Kayiteshonga, Binagwaho, Stulac and Beardslee2012; Boyes et al., Reference Boyes, Cluver and Gardner2012; Boyes and Cluver, Reference Boyes and Cluver2013; Cholera et al., Reference Cholera, Gaynes, Pence, Bassett, Qangule, Macphail, Bernhardt, Pettifor and Miller2014; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Mazenga, Devandra, Ahmed, Kazembe, Yu, Nguyen and Sharp2014),

b pilot study conducted or local validation of instruments (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Scorza, Meyers-Ohki, Mushashi, Kayiteshonga, Binagwaho, Stulac and Beardslee2012; Mpango et al., Reference Mpango, Kinyanda, Rukundo, Gadow and Patel2017)

Prevalence of psychological symptoms

Four studies reported emotional and behavioral difficulties, assessed by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, Scanlon, Marete, Mwangi, Inui, McAteer and Nyandiko2015; Gentz et al., Reference Gentz, Romano, Martínez-Arias and Ruiz-Casares2017; Lyambai and Mwape, Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018). The lowest prevalence was reported by Vreeman et al., from a sample of younger adolescents (n = 285; age 10–14) enrolled in a disclosure intervention trial in Kenya (Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, Scanlon, Marete, Mwangi, Inui, McAteer and Nyandiko2015): 9% scored in the borderline range and 5% in the clinical range. Two other studies, conducted in Zambia (n = 99; age 12–18) and Namibia (n = 127; age 11–15), reported a prevalence of 28.5% and 29.1% for emotional and behavioral problems (borderline and clinical range) (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009; Gentz et al., Reference Gentz, Romano, Martínez-Arias and Ruiz-Casares2017). Another study from Zambia (n = 103; age 11–17) reported on the percentage that scored in the clinical range (29.2%) (Lyambai and Mwape, Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018). Menon et al., compared a sample of HIV-positive adolescents (n = 127) to a sample of school children (n = 420) (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009) and found a comparable prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems (29.1 v. 27.8%). Three studies also reported results for the different subscales of the SDQ (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009; Gentz et al., Reference Gentz, Romano, Martínez-Arias and Ruiz-Casares2017; Lyambai and Mwape, Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018): In the sample from Namibia (Gentz et al., Reference Gentz, Romano, Martínez-Arias and Ruiz-Casares2017), emotional problems were more prevalent (22%) than conduct problems (12.2%), peer problems (10.9%) or hyperactivity/inattention (4%). The two other studies, both from Zambia, found a higher frequency of peer problems (46.9% and 41.8%, respectively), compared to emotional or conduct problems (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009; Lyambai and Mwape, Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018). Peer problems were also frequent in the sample of unaffected school children that was used as a control group (34.4%). Lyambai and Mwape compared self-rated results to parent-rated results and found that parents reported fewer problems in each of the categories (Lyambai and Mwape, Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018) and this was most prominent for peer problems.

Musisi and Kinyanda (Reference Musisi and Kinyanda2009) made use of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire 25 (SRQ-25) to assess significant psychological distress among a sample of HIV-positive adolescents (n = 82; age 10–18) from Uganda and reported a prevalence of 51%.

Symptoms of depression were assessed in five of the studies (Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, Scanlon, Marete, Mwangi, Inui, McAteer and Nyandiko2015; Smith Fawzi et al., Reference Smith Fawzi, Ng, Kanyanganzi, Kirk, Bizimana, Cyamatare, Mushashi, Kim, Kayiteshonga, Binagwaho and Betancourt2016; Woollett et al., Reference Woollett, Cluver, Bandeira and Brahmbhatt2017; Okawa et al., Reference Okawa, Kabaghe, Mwiya, Kikuchi, Jimba, Kankasa and Ishikawa2018; Kemigisha et al., Reference Kemigisha, Zanoni, Bruce, Menjivar, Kadengye, Atwine and Rukundo2019). In a sample from Zambia (n = 190; age 15–19), 25.3% of adolescents had high scores of depressive symptoms, according to the short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Okawa et al., Reference Okawa, Kabaghe, Mwiya, Kikuchi, Jimba, Kankasa and Ishikawa2018). Of the total, 69% of symptomatic adolescents were female and 31% were male. A similar prevalence (26%) was reported in a study from Rwanda (n = 193; age 10–17) that used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC) (Smith Fawzi et al., Reference Smith Fawzi, Ng, Kanyanganzi, Kirk, Bizimana, Cyamatare, Mushashi, Kim, Kayiteshonga, Binagwaho and Betancourt2016). In a younger sample from western Kenya (n = 285; age 10–14), 19% of adolescents scored positive for depression, according to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). However, 15% showed minimal, 3% minor, and 2% moderate or severe symptoms (Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, Scanlon, Marete, Mwangi, Inui, McAteer and Nyandiko2015). In a sample from deprived urban neighborhoods of Johannesburg, South Africa, 14% of adolescents (n = 343; median age 16) showed symptoms of depression, according to the Child Depression Inventory (CDI) (Woollett et al., Reference Woollett, Cluver, Bandeira and Brahmbhatt2017)

Anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were only reported from the South African sample (Woollett et al., Reference Woollett, Cluver, Bandeira and Brahmbhatt2017). Assessment with the Revised Children´s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) and the Child PTSD Checklist revealed that 25% of adolescents had symptoms of anxiety and 5% had symptoms of PTSD. Furthermore, 27% of participants were symptomatic for either depression, anxiety, or PTSD. Female adolescents had significantly higher scores of depression, anxiety, or PTSD, compared to male adolescents.

Three studies assessed suicidality: In the sample of Woollett et al., 24% reported suicidal ideation and 5% suicide attempts during the previous month. Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Kirk, Kanyanganzi, Fawzi, Sezibera, Shema, Bizimana, Cyamatare and Betancourt2015) reported on suicidal ideation and behavior from Rwanda, using the Youth Self-Report (YSR), internalizing subscale. In their matched case-control study (n = 683; age 10–17), 21% of HIV-positive adolescents reported suicidal behavior (including self-harm) during the previous 6 months, compared to 13% of unaffected adolescents. Kemigisha et al. (Reference Kemigisha, Zanoni, Bruce, Menjivar, Kadengye, Atwine and Rukundo2019) reported a lower prevalence of suicidal ideation (7.7%) from a sample in western Uganda (n = 336; age 10–19). In total, 69.2% of adolescents reporting suicidal ideation were female and 30.8% were male. Furthermore, 81% of adolescents reporting suicidality also scored positive for depression.

Prevalence of mental disorders

The prevalence of mental disorders was assessed by structured or semi-structured diagnostic interviews [MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Children´s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R)] in three studies (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Mazenga, Yu, Devandra, Nguyen, Ahmed, Kazembe and Sharp2015; Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Bakare, Edet, Igwe, Ewa, Bankole and Olose2017; Ashaba et al., Reference Ashaba, Cooper-Vince, Maling, Rukundo, Akena and Tsai2018). Another study used symptom count scores from the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory-5 (CASI-5) and the Youth´s Inventory-4R (YI-4R) (Kinyanda et al., Reference Kinyanda, Salisbury, Levin, Nakasujja, Mpango, Abbo, Seedat, Araya, Musisi, Gadow and Patel2019). Musisi and Kinyanda (Reference Musisi and Kinyanda2009) assessed mental disorders in an ICD-10-based, diagnostic psychiatric interview, not further specified.

An overall prevalence of any psychiatric disorder was reported from a sample of perinatally infected adolescents in Uganda (n = 479; age 12–17) (Kinyanda et al., Reference Kinyanda, Salisbury, Levin, Nakasujja, Mpango, Abbo, Seedat, Araya, Musisi, Gadow and Patel2019). Based on symptom count scores (either caregiver- or self-report), 23.8% of adolescents scored positive for a psychiatric disorder, with 18.2% scoring positive for any emotional disorder and 12.4% for any behavioral disorder. The level of comorbidity between emotional and behavioral disorders was 38.6% and 22.5%, respectively. ADHD was the most prevalent behavioral disorder (6.4%) and anxiety disorders were the most prevalent type of emotional disorders (14.7%). The prevalence of major depressive disorder was 5.2%. Prevalence according to self-report alone were much lower (ADHD 3.1%, anxiety 10.1%, major depressive disorder 0.2%).

The prevalence of depressive disorder was 18.9% in a large sample (n = 562; age 12–18) from Malawi (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Mazenga, Yu, Devandra, Nguyen, Ahmed, Kazembe and Sharp2015). A comparable prevalence (16%) was found in a sample from rural Uganda (n = 224; age 13–17) (Ashaba et al., Reference Ashaba, Cooper-Vince, Maling, Rukundo, Akena and Tsai2018) and 14% of the sample reported suicidality in the previous month, with 4% having a high suicide risk.

In a sample from Nigeria (n = 31; age 11–16), 41.9% were diagnosed with depression, with the highest prevalence (83.3%) found in the 14–16 years age group (Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Bakare, Edet, Igwe, Ewa, Bankole and Olose2017). For their whole study group (aged 6–16), Bankole et al., showed that depression and suicidality were more prevalent among ALHIV, compared to controls. An older study from Uganda (n = 82; age 10–18) found a depression prevalence of 40.8% (Musisi and Kinyanda, Reference Musisi and Kinyanda2009). In the same sample, 45.6% of adolescents were diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, 18% with somatization disorder, and 1.2% with bipolar disorder (mania). Furthermore, 19.5% reported ever having made a suicide attempt and 17.1% had attempted suicide within the past 12 months.

Associations with sociodemographic, health-related and community factors

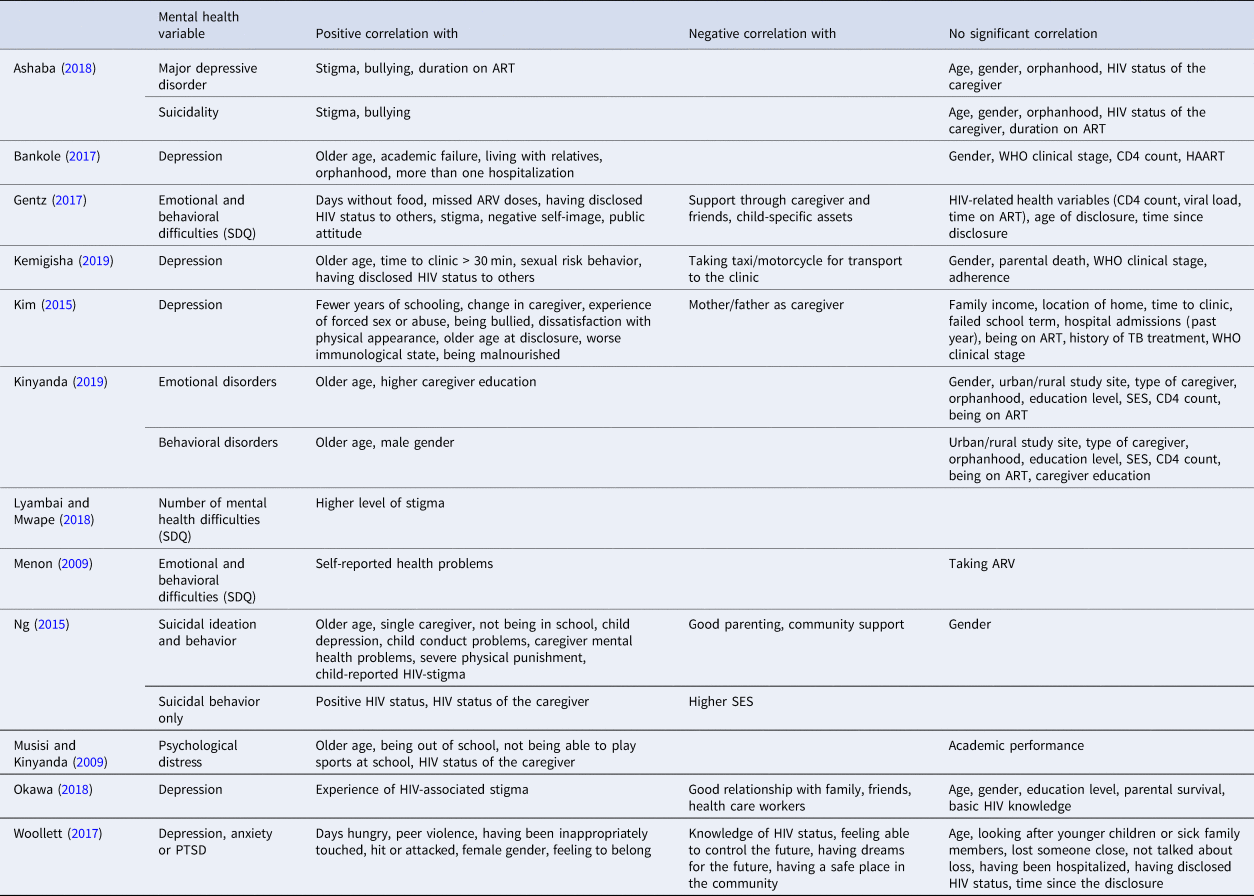

Twelve studies assessed correlations between mental health and explanatory factors, either by chi-square or t-test (Table 3) or by regression analysis (Table 4).

Table 3. Mental health outcomes and correlations found by bivariate analysis

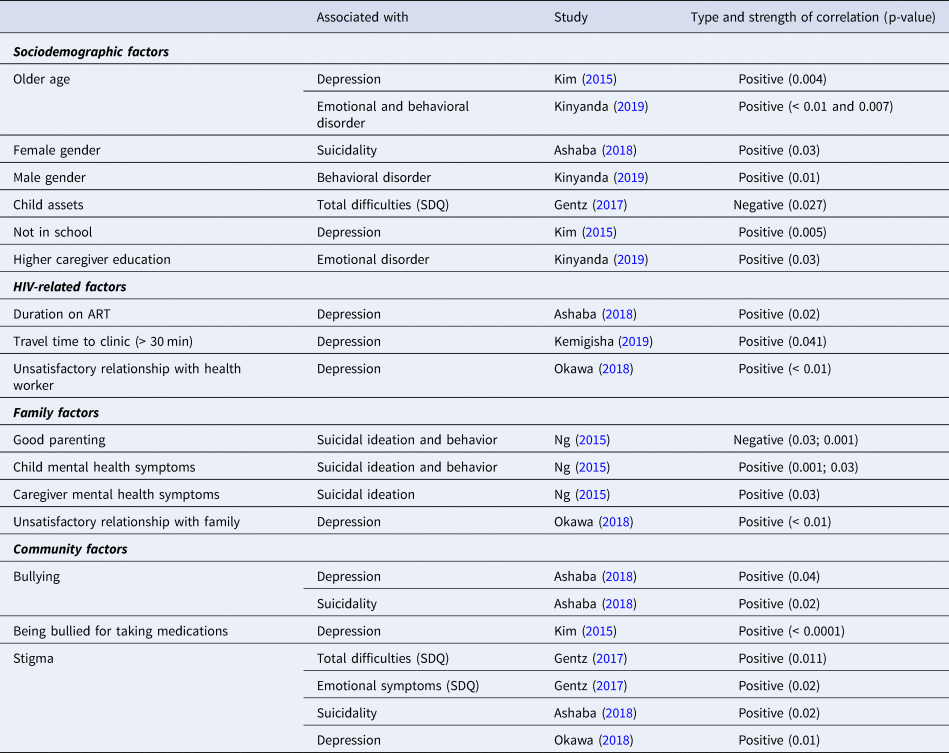

Table 4. Sociodemographic, family, and community factors associated with mental health found by multiple logistic or hierarchical regression

Findings on associated factors from bivariate analyses were often contradictory (Table 3). This applied to most of the sociodemographic variables (age, gender, socioeconomic status, education level/academic performance, orphanhood, HIV status of the caregiver). For health-related variables, WHO clinical stage, CD4 count, or being on ART were not associated with mental health problems in most studies, while self-reported health problems, being out of school, and not being able to play sports in school were. Disclosure of HIV or time since the disclosure was not associated with mental health problems, whereas two studies found an association between having disclosed HIV status to others and poor mental health. Findings on mental health and ART adherence were also contradictory.

Bullying and stigma were consistently associated with poor mental health outcomes. Poverty (days hungry or non-availability of child assets) and the experience of violence or abuse were associated with poor mental health. Social support through community, family, or friends, and good parenting were associated with better mental health outcomes in several studies. Individual-level factors such as feeling able to control the future and having dreams for the future were likewise associated with better mental health.

Factors identified by logistic regression are shown in Table 4. Apart from sociodemographic and HIV-related factors, family factors (good parenting, relationship with family, child and caregiver mental health) were identified as important predictors of mental health. With regard to community-level factors, bullying and stigma predicted poor mental health outcomes.

Two other studies explored the factors associated with non-adherence, using mental health as an independent variable in logistic regression (Smith Fawzi et al., Reference Smith Fawzi, Ng, Kanyanganzi, Kirk, Bizimana, Cyamatare, Mushashi, Kim, Kayiteshonga, Binagwaho and Betancourt2016; Okawa et al., Reference Okawa, Kabaghe, Mwiya, Kikuchi, Jimba, Kankasa and Ishikawa2018). Smith Fawzi et al., found a significant association between conduct problems and non-adherence and also, though weaker, between self-reported depression and non-adherence. Okawa et al., did not find a significant association between depressive symptoms and non-adherence.

Discussion

The vast majority of adolescents living with HIV reside in sub-Saharan Africa. To date, there has not been a specific review of the burden of mental health problems for this high-risk population in this region of the world. We summarized the relevant evidence for this high-risk group as part of a systematic review on mental health problems among sub-Saharan adolescents based on peer-reviewed studies published between 2008 and 2019. Collectively, the studies indicated a high prevalence of mental health problems, with 24–27% of adolescents scoring positive for any psychiatric disorder and 30–50% showing emotional or behavioral difficulties or significant psychological distress. Based on regression analyses, older age, not being in school, poverty, and bullying and stigma predicted mental health problems. Social support and parental competence were protective.

The high prevalence of mental health problems among HIV-positive adolescents found in this review aligns with previous research on HIV-positive adolescents in both, high- and low-income settings (Mellins and Malee, Reference Mellins and Malee2013; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, McCoy and Lee2017). The prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems, depression, and anxiety was in the same range as the prevalence reported by Mellins and Malee from the USA, while ADHD was much more common in the US studies. Case-control studies indicated a higher prevalence of suicidality and depression among HIV-positive adolescents, compared to controls (Ng et al., Reference Ng, Kirk, Kanyanganzi, Fawzi, Sezibera, Shema, Bizimana, Cyamatare and Betancourt2015; Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Bakare, Edet, Igwe, Ewa, Bankole and Olose2017), while the prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems did not differ between the two groups (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009).

Associations with sociodemographic, health-related, and community factors

Sociodemographic factors associated with mental health problems in regression analyses were older age, poverty, not being in school, and higher caregiver education. Unsatisfactory relationships with health workers, longer travel time to clinic, and duration on ART were health-related factors associated with poor mental health. Stigma and bullying were strong community-level predictors for mental health problems. Factors associated with better mental health outcomes included social support and good parenting.

The factors described above are not much different from the risk factors known for mental health problems in general adolescent populations (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Flisher, Hetrick and McGorry2007; Fisher and Cabral de Mello, Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Izutsu, Vijayakumar, Belfer and Omigbodun2011; Kieling et al., Reference Kieling, Baker-Henningham, Belfer, Conti, Ertem, Omigbodun, Rohde, Srinath, Ulkuer and Rahman2011; WHO, 2012; WHO, 2013a).This raises the question of whether it is the HIV infection itself or rather environmental and family factors that pose a risk to mental health (Mellins and Malee, Reference Mellins and Malee2013; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, McCoy and Lee2017). As the majority of HIV-positive adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa were perinatally infected, they also have to cope with the consequences of familial AIDS: bereavement, caring for ill family members with AIDS, stigma and discrimination, poverty, lack of social support and guidance and diminished educational opportunities (Lowenthal et al., Reference Lowenthal, Bakeera-Kitaka, Marukutira, Chapman, Goldrath and Ferrand2014). A study from Kenya on vertically infected and HIV-affected adolescents found similar depression scores in both groups, with orphanhood, poverty, and caregiver depression being associated factors (Abubakar et al., Reference Abubakar, Van de Vijver, Hassan, Fischer, Nyongesa, Kabunda, Berkley, Stein and Newton2017). Ng et al. (Reference Ng, Kirk, Kanyanganzi, Fawzi, Sezibera, Shema, Bizimana, Cyamatare and Betancourt2015) found similar rates of suicidality among HIV-positive and HIV-affected adolescents and correlations with caregiver´s mental health. The relevance of caregiver health and child-caregiver relationship for mental health outcomes in this population is known from previous research (Bhana et al., Reference Bhana, Mellins, Small, Nestadt, Leu, Petersen, Machanyangwa and McKay2016; Louw et al., Reference Louw, Ipser, Phillips and Hoare2016; Boyes et al., Reference Boyes, Cluver, Meinck, Casale and Newnham2019).

HIV disclosure and adherence to ART

The disclosure of HIV was not identified as a predictive factor for mental health in regression models. The bivariate analysis suggested no adverse effects of disclosure, but associations between mental health problems and disclosure of HIV status to others. WHO strongly recommends timely disclosure (WHO, 2013b). Studies from this review found that knowledge of HIV status was associated with better mental health (Woollett et al., Reference Woollett, Cluver, Bandeira and Brahmbhatt2017), while older age at disclosure was associated with mental health problems (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Mazenga, Yu, Devandra, Nguyen, Ahmed, Kazembe and Sharp2015). Ramos et al. showed that HIV-positive youth (aged 11–24) who had to figure out their HIV status on their own were more likely to show mental health symptoms and internal stigma, compared to youth who were disclosed to (Ramos et al., Reference Ramos, Mmbaga, Turner, Rugalabamu, Luhanga, Cunningham and Dow2018). Incomplete adherence to ART was also more likely among youth not disclosed to.

Findings on mental health as an independent factor for ART adherence were contradictory (Smith Fawzi et al., Reference Smith Fawzi, Ng, Kanyanganzi, Kirk, Bizimana, Cyamatare, Mushashi, Kim, Kayiteshonga, Binagwaho and Betancourt2016; Okawa et al., Reference Okawa, Kabaghe, Mwiya, Kikuchi, Jimba, Kankasa and Ishikawa2018). Other studies reported a positive association between poor mental health and non-adherence (Dow et al., Reference Dow, Turner, Shayo, Mmbaga, Cunningham and O'Donnell2016; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, McCoy and Lee2017) or virologic failure (Lowenthal et al., Reference Lowenthal, Lawler, Harari, Moamogwe, Masunge, Masedi, Matome, Seloilwe and Gross2012). A systematic review of the factors associated with adherence to ART in LMIC did not identify mental health as one of the most prominent factors for adherence (Hudelson and Cluver, Reference Hudelson and Cluver2015). A large study from the Eastern Cape, South Africa, found that perinatally infected adolescents were more likely to be adherent, compared to behaviorally infected adolescents (Sherr et al., Reference Sherr, Cluver, Toska and He2018). Simultaneously, behaviorally infected adolescents showed higher scores of depression, anxiety, and suicidality and were more likely to report internalized stigma and substance use. None of the studies included in this review explored the mode of infection as a predictive factor for mental health and/or adherence. The study of Sherr et al., suggests that the mode of infection might be an important factor for both mental health outcomes and retention in care and that it also has an influence on how adolescents are treated by health care workers.

Implications for HIV care

Given the high prevalence of mental health problems among HIV-positive adolescents, identifying and addressing these problems is crucial. Screening for mental health problems and integrating mental health care into regular HIV services is highly recommended (Musisi and Kinyanda, Reference Musisi and Kinyanda2009; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Mazenga, Yu, Devandra, Nguyen, Ahmed, Kazembe and Sharp2015; Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Bakare, Edet, Igwe, Ewa, Bankole and Olose2017; Gentz et al., Reference Gentz, Romano, Martínez-Arias and Ruiz-Casares2017; Woollett et al., Reference Woollett, Cluver, Bandeira and Brahmbhatt2017; Lyambai and Mwape, Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018; Okawa et al., Reference Okawa, Kabaghe, Mwiya, Kikuchi, Jimba, Kankasa and Ishikawa2018).

Lyambai and Mwape (Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018) conducted qualitative interviews among nurses working at an ART clinic. Mental health literacy among health care workers was low and there was no dedicated mental health service for HIV-positive adolescents available. HIV-positive adolescents face multiple challenges in the context of HIV: daily adherence to medications, coping with the diagnosis, coping with an AIDS-ill caregiver and/or bereavement, coping with stigma and discrimination from peers, disclosure to potential partners, and negotiating safer sex (Lowenthal et al., Reference Lowenthal, Bakeera-Kitaka, Marukutira, Chapman, Goldrath and Ferrand2014; Bryant and Beard, Reference Bryant and Beard2016). For many adolescents, the transition from pediatric services to adult HIV care is critical, with a high risk of discontinuation of treatment at this point (Lowenthal et al., Reference Lowenthal, Bakeera-Kitaka, Marukutira, Chapman, Goldrath and Ferrand2014; Bryant and Beard, Reference Bryant and Beard2016; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, McCoy and Lee2017). Addressing their psychosocial needs and well-being is crucial to keeping adolescents in care.

There are multiple approaches for improving the mental health of HIV-positive adolescents, e.g. enhancement of self-regulation skills and coping strategies (Bhana et al., Reference Bhana, Mellins, Small, Nestadt, Leu, Petersen, Machanyangwa and McKay2016; Mutumba et al., Reference Mutumba, Bauermeister, Harper, Musiime, Lepkowski, Resnicow and Snow2017), and strengthening resources for social support (Casale et al., Reference Casale, Boyes, Pantelic, Toska and Cluver2019). As HIV likely affects the whole family, there is a need for evidence-based family interventions, the VUKA family program being one promising example (Bhana et al., Reference Bhana, Mellins, Petersen, Alicea, Myeza, Holst, Abrams, John, Chhagan, Nestadt, Leu and McKay2014; Mellins et al., Reference Mellins, Nestadt, Bhana, Petersen, Abrams, Alicea, Holst, Myeza, John, Small and McKay2014). Addressing stigma is another important issue. To inform mental health promotion and program planning, it is crucial to understand the psychosocial challenges HIV-positive adolescents face (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Myeza, Alicea, John, Holst, McKay and Mellins2010; Ashaba et al., Reference Ashaba, Cooper-Vince, Vořechovská, Rukundo, Maling, Akena and Tsai2019a).

Differences in methodology and prevalence between the studies

As different samples are exposed to a different set of risk and protective factors, differences in prevalence are comprehensible (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Izutsu, Vijayakumar, Belfer and Omigbodun2011; Kieling et al., Reference Kieling, Baker-Henningham, Belfer, Conti, Ertem, Omigbodun, Rohde, Srinath, Ulkuer and Rahman2011). Apart from community and family factors, the percentage of adolescents receiving ART, differences in HIV-related physical health, and the quality of HIV care will have an impact on the prevalence of mental health problems (Okawa et al., Reference Okawa, Kabaghe, Mwiya, Kikuchi, Jimba, Kankasa and Ishikawa2018; Boyes et al., Reference Boyes, Cluver, Meinck, Casale and Newnham2019).

Two studies on younger adolescents reported a low prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems, almost comparable to the general adolescent population (Menon et al., Reference Menon, Glazebrook and Ngoma2009; Vreeman et al., Reference Vreeman, Scanlon, Marete, Mwangi, Inui, McAteer and Nyandiko2015). This may be due to the fact that the prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents rises with age (de Girolamo et al., Reference de Girolamo, Dagani, Purcell, Cocchi and McGorry2012; WHO, 2017).

Differences between self- and caregiver-report were described in two of the studies (Lyambai and Mwape, Reference Lyambai and Mwape2018; Kinyanda et al., Reference Kinyanda, Salisbury, Levin, Nakasujja, Mpango, Abbo, Seedat, Araya, Musisi, Gadow and Patel2019). van den Heuvel et al. (Reference van den Heuvel, Levin, Mpango, Gadow, Patel, Nachega, Seedat and Kinyanda2019) explored agreement and discrepancies between caregiver- and self-reported results from the sample of Kinyanda et al., and only found a modest correlation between the two. A low inter-informant agreement was also reported by Doku and Minnis (Reference Doku and Minnis2016) from a sample of HIV-affected children and their caregivers. Thus, the prevalence of mental health problems may vary according to the type of informant.

Reviews on child and adolescent mental health found that studies that used screening instruments reported higher rates of mental health problems, compared to studies that used diagnostic interviews (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Izutsu, Vijayakumar, Belfer and Omigbodun2011; Cortina et al., Reference Cortina, Sodha, Fazel and Ramchandani2012). This is also true for most of the studies in this review. Only two studies with very small sample sizes that employed diagnostic interviews reported exceptionally high rates of depressive disorder (Musisi and Kinyanda, Reference Musisi and Kinyanda2009; Bankole et al., Reference Bankole, Bakare, Edet, Igwe, Ewa, Bankole and Olose2017).

Limitations

Most of the studies used self-reporting screening instruments. As screening instruments can merely identify symptomatic people or people with a probable psychiatric disorder, results from screening instruments are not equivalent to disorder prevalence. Using screening instruments can result in an overestimation of disorder prevalence, as could be shown for depression screening among people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (Tsai, Reference Tsai2014). Particularly when used in settings with a low expected prevalence, there is a considerable risk of misclassification (Kagee et al., Reference Kagee, Tsai, Lund and Tomlinson2013; Stockings et al., Reference Stockings, Degenhardt, Lee, Mihalopoulos, Liu, Hobbs and Patton2015).

Self-reported results are prone to reporting bias and may be influenced by social desirability, so results have to be interpreted with caution. Where sensitive issues are concerned, there is a considerable risk of underreporting. Most studies used convenience sampling which has an impact on the representativeness of the data. As the vast majority of studies were cross-sectional, no causal relationships can be derived from the results. Most of the studies did not use control groups, which makes it difficult to differentiate between HIV-related mental health risks and risks that adolescents share with their peers from the same community.

The majority of standardized screening instruments and diagnostic interviews in use in the field of child and adolescent mental health today were developed in high-income settings. Questions developed and tested in high-income settings may be inappropriate when used in a low-resource setting, which can lead to an over- or underestimation of prevalence (Sweetland et al., Reference Sweetland, Belkin and Verdeli2014; Owen et al., Reference Owen, Baig, Abbo and Baheretibeb2016). For many of the standardized instruments used today, there are no clinical cut-offs validated for Africa (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Davids, Mathews and Aarø2018; Hoosen et al., Reference Hoosen, Davids, de Vries and Shung-King2018). Only a few screening instruments were either developed with HIV-positive or HIV-affected adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa or were validated and adapted for use within this population (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Rubin-Smith, Beardslee, Stulac, Fayida and Safren2011; Ng et al., Reference Ng, Kanyanganzi, Munyanah, Mushashi and Betancourt2014; Mutumba et al., Reference Mutumba, Resnicow, Bauermeister, Harper, Musiime, Snow and Lepkowski2015; Ashaba et al., Reference Ashaba, Cooper-Vince, Vořechovská, Maling, Rukundo, Akena and Tsai2019b). The majority of these instruments have not been used on a larger scale. The inclusion of studies that used locally developed instruments and also of qualitative studies could have led to a more precise understanding of the mental health issues in the HIV-positive adolescent population. To achieve better comparability of the data, we focused on prevalence rates that were determined using standardized measures only. By only including studies reporting point prevalence data, we cannot draw any conclusions on the trajectories of adolescents living with HIV. This is a crucial topic for future research. For children orphaned by AIDS, Cluver et al. (Reference Cluver, Orkin, Gardner and Boyes2012) have shown that mental health problems worsened over time. This may also be true for HIV-positive adolescents.

The number of databases that were searched was limited due to time and capacity restrictions, though the most important ones were included. Because we focused on peer-reviewed articles only, EMBASE and conference websites were not searched. The inclusion of studies in other languages than English may have led to additional findings. Because of our focus on adolescents aged 10–19, publications employing a broader age than 10–19, reporting prevalence data for children and adolescents or for adolescents and young people up to the age of 24 may have been missed. Due to publication bias, studies that found a high prevalence of mental health problems may be overrepresented. As the review was conducted within an adolescent mental health promotion project in South Africa and Zambia, both countries were included in the search terms which might have led to an overrepresentation of studies from these two countries. Furthermore, the results presented here are a subsection of a larger systematic review and the comparability of the findings to the general sub-Saharan adolescent population, as well as other high-risk groups, can only be commented on once the other sections of the review have been published. Lastly, the review was limited to the period 2008 and 2019 and so studies published before and after this period, which may be informative, were excluded.

Conclusion

This review updates and synthesizes evidence on the prevalence of mental health problems among HIV-positive adolescent populations in sub-Saharan Africa. Mental health problems are highly prevalent in this population and need to be addressed within regular HIV care settings. Poor mental health can be associated with non-adherence to ART and with other risk behaviors, leading to poorer physical outcomes and a higher risk of HIV transmission. Health care professionals working with HIV-positive adolescents should be enabled to recognize mental health problems and respond to them in an appropriate, non-discriminatory way to ensure the best possible outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2020.18.

Acknowledgements

This review is part of the MEGA project ‘Building capacity by implementing mhGAP mobile intervention in SADC countries’ which was supported by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union (Capacity Building 585827-EPP-1-2017-1-FI-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP).

The work by Leigh van den Heuvel reported herein was made possible through funding by the South African Medical Research Council through its Division of Research Capacity Development under the SAMRC Clinician Researcher M.D. PhD Scholarships Programme from funding received from the South African National Treasury. The content hereof is the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the SAMRC or the funders.

Sharain Suliman received post-doctoral support from the South African Research Chairs Initiative in PTSD funded by the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation and a SAMRC Self-Initiated Research Grant.

Conflict of interest

None.