Introduction

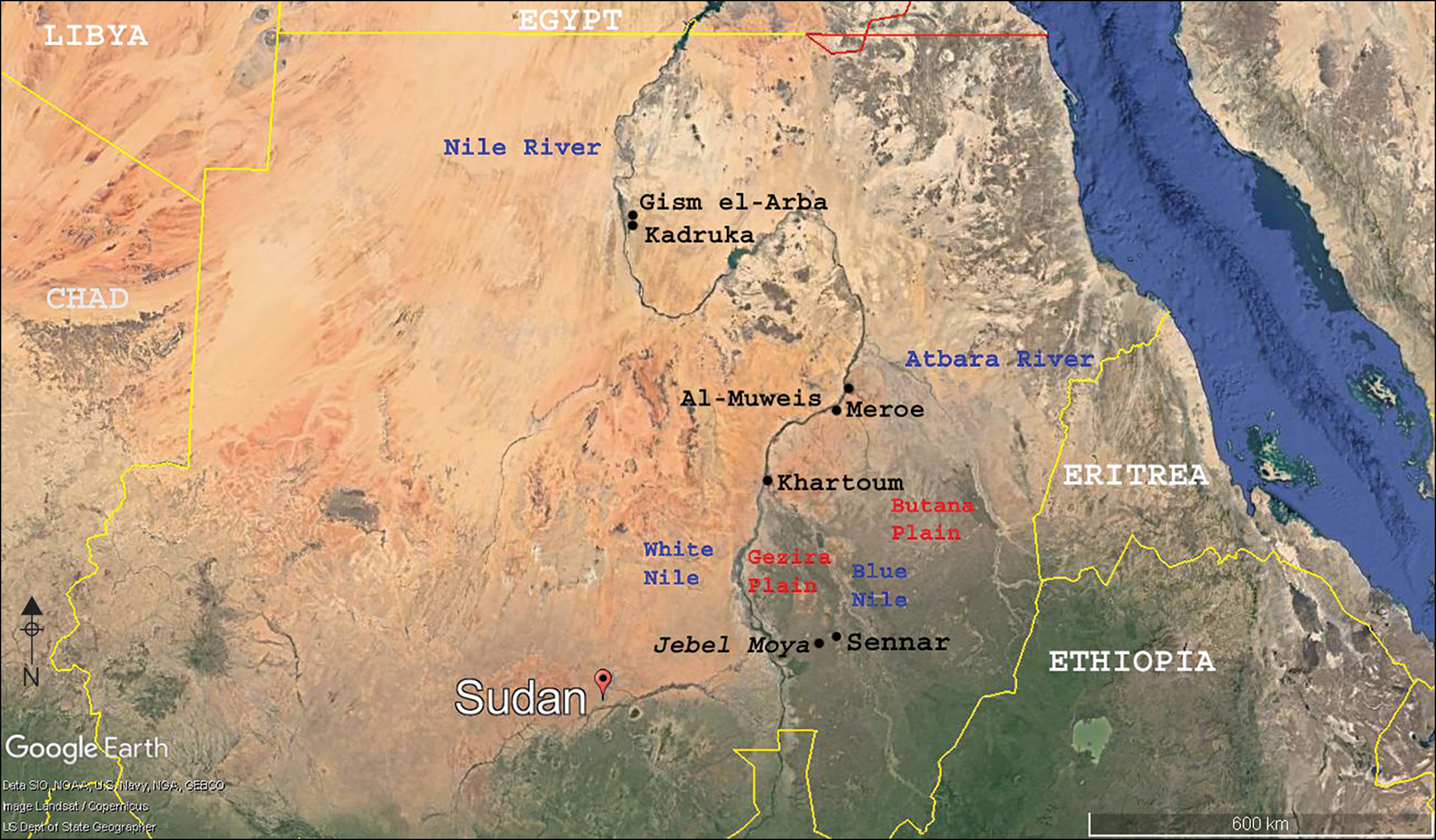

Jebel Moya is the largest known cemetery in the southern Gezira plain of south-central Sudan (Figure 1). Between 1911 and 1914, Henry Wellcome removed 3135 human burials in his search for the origins of an African civilisation. The area, however, remains under-explored. Current excavations are focused on the many biographies of people in and around Jebel Moya, paying particular attention to subsistence, climate change and population health (Brass et al. Reference Brass2019). It is clear that the site's biography dates from at least the late sixth millennium BC to the early first millennium AD. The latter is contemporaneous with the Meroitic state to the north, but it is increasingly clear that this part of Sudan functioned independently of the Meroitic state.

Figure 1. Location of Jebel Moya, Sudan (figure by the authors; map from Google maps).

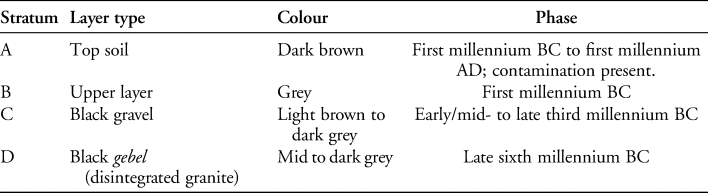

Continuing our dating programme, we report two new dates that show burial activity occurring from at least the second half of the third millennium BC to 2000 years ago. Excavations and analyses have shown an extended chronology and Late Mesolithic non-mortuary activity. This is particularly significant, since Wellcome's team removed a staggering number of burials and, while he mandated a laborious card-recording system, the removal and recording methods led to numerous problems, particulary in terms of chronology, stratigraphic distribution and the associated grave goods. These problems have puzzled a number of scholars, including Frank Addison, who was in charge of the final report, despite having never worked at Jebel Moya (see Addison Reference Addison1949; Gerharz Reference Gerharz1994; Brass Reference Brass2016). The situation is rendered more complex by the site's geology. There are four macro-geological strata, which broadly correspond to chronology (for more detail, see Brass et al. Reference Brass2020) (Table 1).

Table 1. Geological sequence at the Jebel Moya cemetery.

Revising chronologies and burial activity

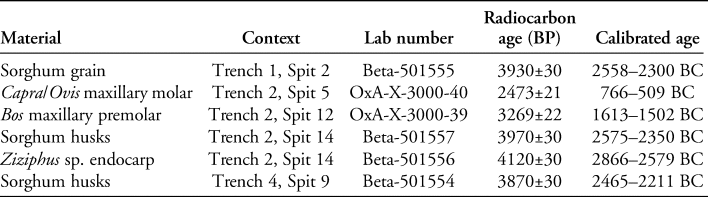

Addison (Reference Addison1949) initially assigned all burials to the Napatan State; he later revised his dates after criticism from Arkell and ultimately settled for the Meroitic (Addison Reference Addison1956). More recently, absolute dates (Table 2) were combined with a more thorough sequence based on detailed excavations and a re-assessment of pottery (Brass et al. Reference Brass2019; Brass & Vella Gregory Reference Brass and Gregory2021).

Table 2. AMS dates (Beta Analytic, and the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art at Oxford University). Calibration: OxCal 4.3.2, IntCal13 at 95.4% confidence (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2013).

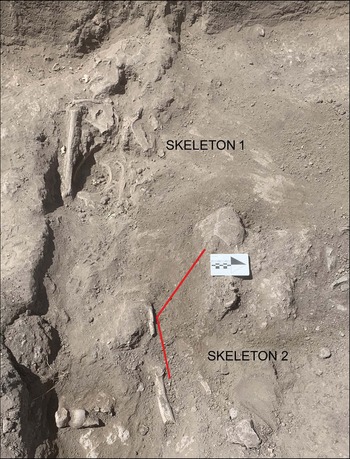

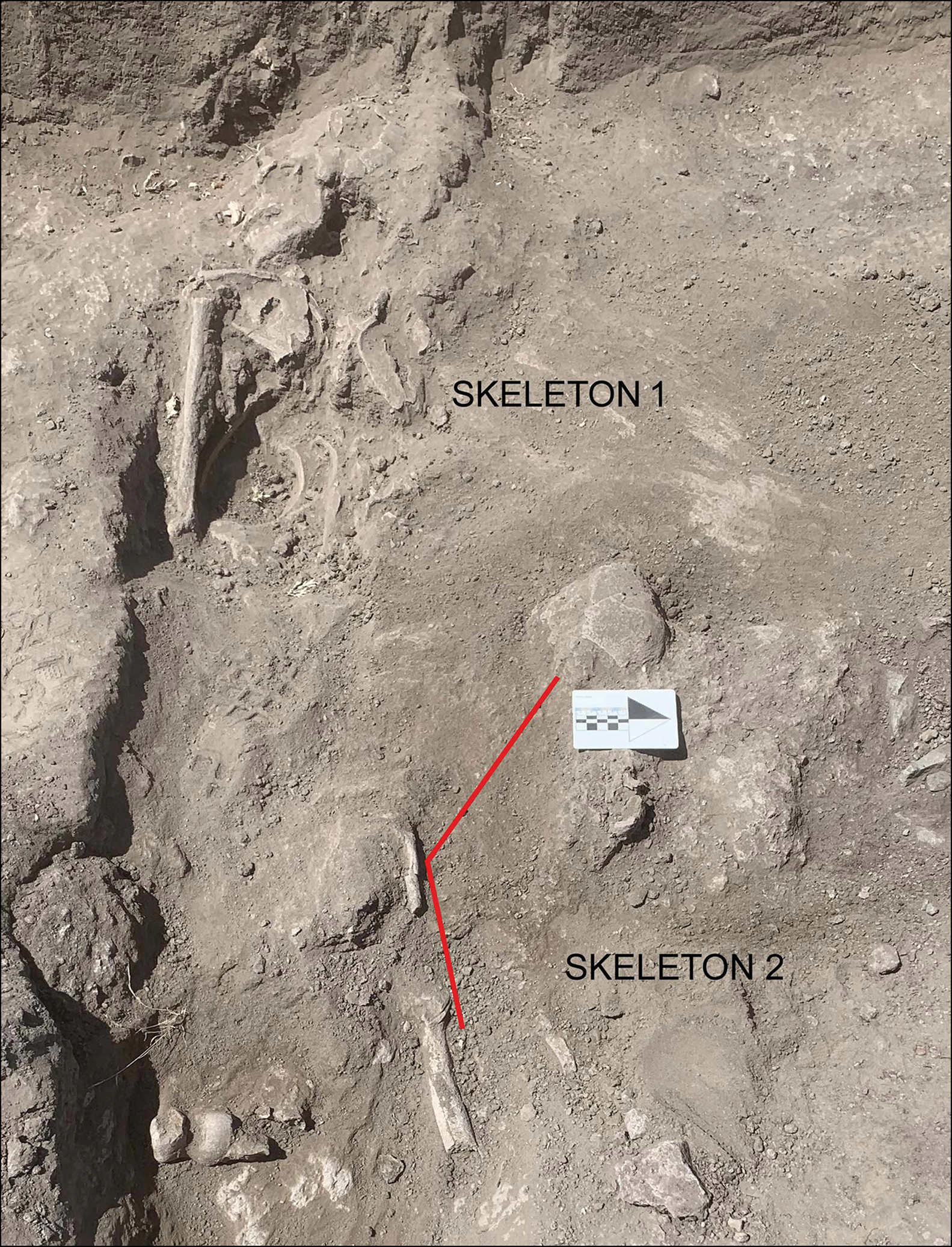

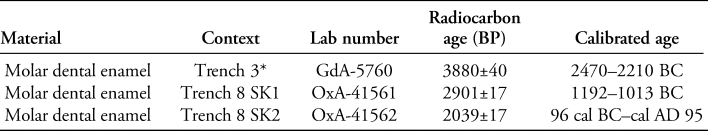

Here, we present two new AMS dates (Table 3). One sample (child, Trench 9) experienced issues during graphitisation resulting in insufficient carbon for a measurement. Two humans in Trench 8 were dated using tooth enamel (Figure 2). Both were deposited in Stratum C. Skeleton 1 is dated to 1192–1013 cal BC, whereas Skeleton 2 dates to between 96 cal BC and cal AD 95; the latter cut into the lower part of Skeleton 1. These results illustrate the complex issues relating to the site's depositional processes and in reconstructing burial activities.

Figure 2. Skeletons 1 and 2, in situ, in the Jebel Moya cemetery (photograph by I. Vella Gregory).

Table 3. AMS dates (Radiocarbon Laboratory, Institute of Physics–Centre for Science and Education at Silesian University of Technology, and the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art at Oxford University). Calibration: OxCal 4.3.2, IntCal13, at 95.4% confidence (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer2013).

* Sample previously reported (Brass et al. Reference Brass2019) and is included here for context.

Skeleton 1's cranium and its upper sternum were placed on the bedrock, which was approximately 390mm beneath the modern ground surface in Trench 8. The individual was laid prone, with their head to the west, facing south. The burial contained a small number of lithics, faunal remains and pottery sherds, as well as a small lip plug by the forehead. Cranial features were inconclusive for sex estimation, which is not unusual in Sudanese skeletal remains. The supraorbital ridges and glabellar profile were smooth and unpronounced, and the frontal slope appeared vertical—features typically associated with a female individual. The mandible, however, was robust and the pubic bone showed masculine morphology. Overall, this individual was probably a young male aged between 25 and 35 years (for methods used in sex and age estimation, see Brass et al. Reference Brass2019). The incisors show wear on the lingual aspect, which is typically observed in teeth used as a tool. A large, worn projectile was found embedded in the sediment, just inside the right elbow, which was tucked under the chest cavity.

Skeleton 2, while poorly preserved, was probably an adult female, approximately 30–40 years old. The mandibular molars displayed moderate to severe occlusal wear. Ante-mortem loss of the lower incisors is possibly related to deliberate removal of teeth (tooth ablation) to insert lip plugs. The AMS dates strongly indicate that this practice survived over many centuries, as is supported by other archaeological and anthropological data from across the Sudan (e.g. Seligman & Seligman Reference Seligman and Seligman1932; MacDonald Reference MacDonald1999; Burnett & Irish Reference Burnett and Irish2017; Lee Reference Lee2018; Simonetti et al. Reference Simonetti2021).

Future directions

These new dates have several implications. Firstly, the date from Skeleton 1 fills in the gap between the mid-second millennium BC and early first millennium BC dates from cattle and sheep/goat teeth (Table 2). Together with Skeleton 2, the burial offers strong indications that there was mortuary activity over a minimum of 2300 years—the first time that this has been confidently documented south of Khartoum. Furthermore, Skeleton 2 is the first directly dated burial at the site—and in south-central Sudan—that is contemporaneous with the more northerly Meroitic state, whose southern political boundary extended just below Khartoum.

Until excavations resumed in 2017, dating remains from Jebel Moya was very difficult. This was due to previous cavalier excavation methods, poor recording, and erosional processes. Our spit-excavation method, combined with field survey and environmental and AMS data, shows that the eastern and central areas of the site are most affected by these conditions. Archival research has also shown that these areas underwent extensive interventions in the early twentieth century, although the area where the skeletons were excavated was not disturbed by Wellcome. Additionally, the western area contains unexcavated, deep stratigraphic deposits. Environmental data clearly indicate that, while there were wetter conditions than present in the third millennium BC, the climate became progressively drier until it reached modern, semi-arid conditions around 2000 years ago. This would have reduced vegetation cover, compounded by erosion from seasonal summer rains. The variable processes and timings of deposition and erosion therefore mean that burials from different time periods can cut across or into each other. More radiocarbon dating of skeletons is vital. For now, this is the first time that continual burial activity has been established at this vital site in the eastern Sahel.

As we continue methodical excavation of this site, research questions need to be balanced by current environmental challenges. Furthermore, it is clear that we need a programme of micro-geological investigations across the site, sequences and samples for which are readily available (particularly from Trench 2 and the western half of the valley). This work will not only elucidate the geological processes but will also help further refine excavation methods in this type of environment. For further information and updates on the project, see: https://thejebelmoyaproject.wordpress.com.

Funding statement

The excavations were funded by the Society for Libyan Studies. AMS radiocarbon dates were sponsored by Pontus Skoglund at the Francis Crick Institute.