To paraphrase Krouwel’s (Reference Lijphart2012, 288) closing sentence in a book that proposes a meta-typology of existing typologies of political parties, how silly would it be to suggest a new party classification?Footnote 1 And yet, a new classification is just what is needed in the age of personalized politics, brought about by the process of political personalization (Cross, Katz, and Pruysers Reference Cross and Pilet2018; Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018). A slew of new parties have been established as mere platforms for politicians: sometimes for their leader and at other times for their politicians, in the plural. Older parties have either resisted and clung to their collegial habits or adapted and created a new equilibrium between the personal and the collegial. These developments touch on the essence of politics: power and the collective action problem.

This article proposes a new party classification that is suited to personalized politics. In addressing the essence of politics (power) and party organization (collective action), this is a timely research tool that stands strong in comparison to existing typologies in terms of simplicity and parsimony, universalism, usefulness, and time resistance. It is not intended to replace useful existing typologies but rather to join, on its own merits, that club. A collection of typologies is needed because “there is no one universally valid scheme.… The utility of a schema depends in part on what we want to know,” and “a classification useful for one purpose may not be useful for another” (Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002, 149).

The article’s first part reviews the comprehensive and abstractive descriptive value of party classifications and typologies and shows how the proposed new classification addresses their inherent limitations. The second part explains the need for this new classification: it addresses the rise of the personalization of politics in general and of parties in particular, as well as theoretical concerns that pertain to politics and party politics. It also demonstrates that existing classifications and typologies are not sensitive enough to personalized politics: although some types that touch on personalized politics have been added, there has been no systematic attempt to fully contrast them with the collegial option. The third part outlines the new classification and its five ideal types of political parties: two personalized-decentralized types—collections of separated autonomous activists (movement) or separated autonomous individual politicians (network); a collegial type, focusing on the centrality of the team and collective authorities and decision making; and two personalized-centralized types, which are about either an individual politician in her capacity as the party leader (leader) or the centrality of a specific individual (personal). The next part offers an operationalization of the classification, listing five indicators that differentiate these party types and enable us to identify where power lies. It then uses the operationalization to demonstrate the value of the classification by looking at real-world examples. Finally, the article assesses the advantages and limitations of the proposed classification.

Why We Need Typologies and Classifications, and the Proposed New Classification

A key reason for creating a classification or typology of parties with Weberian ideal types is its comprehensive and abstractive descriptive value.Footnote 2 Katz and Mair (Reference Kenig, Cross, Pruysers and Rahat2018, 128) call a typology a “theoretical primitive, used to theorize about relationships and processes in the absence of the messy complications of the real world.” As such, ideal types provide “easily understandable labels that will help the reader more easily comprehend otherwise complex, multidimensional concepts” (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003, 172). Typologies facilitate the development of a common standardized research language, enabling research to advance, without the need to start every new study from point zero.

Ideal party types play a role in the diachronic analysis of party evolution (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995; Reference Kenig, Cross, Pruysers and Rahat2018) and in synchronic comparisons (Duverger Reference Duverger1965; Kirchheimer Reference Kitschelt, Crotty and Katz1966), and even do so simultaneously (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003). Because they summarize characteristics that are spread among many parties in various countries, scholars also use them to develop methodological tools (Krouwel Reference Lijphart2012) and diagnose problems of contemporary party democracy (Ignazi Reference Karvonen2017; Katz and Mair Reference Kenig, Cross, Pruysers and Rahat2018).

The inherent limitation of this tool is that “one should not expect that real-world political parties fully conform to all of the criteria that define each party model; similarly, some parties may include elements of more than one ideal type” (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003, 172). The classification proposed here includes ideal types, which could serve as milestones in mapping the evolution of parties (especially, but not solely, in the context of political personalization) and as yardsticks in mapping parties at a specific point in time (especially, but not solely, in the context of personalized politics). It does not delineate strictly nominal categories. Most, if not all, real-world cases are expected to fall in between these ideal types. Here, for simplicity’s sake, they are presented along a continuum, extending from decentralized personalism, a situation in which individuals have greater importance relative to the political group; to collegialism, whereby the political group is more important relative to individual politicians; and on to centralized personalism, where a single individual politician is more important relative to political groups.Footnote 3 Following this logic, the model can be adapted to develop diverse types of operationalizations for large-n analysis on an ordinal scale and may even be utilized to fit interval and ratio scales. These differentiations may also be perceived as axes on a two-dimensional map (collegialism as a zero-point, y axis for centralized personalism, and x axis for decentralized personalism) or a triangular-shaped space (with collegialism, centralized personalism, and decentralized personalism at each vertex).

Why a New Classification? Political Personalization and Beyond

Before explaining why the proposed classification is needed, it is necessary to briefly clarify its main guiding logic. Put simply, it differentiates among parties—perceived according to their minimalist definition as organizations that present candidates for public positions—and determining whether they are collegial or personalized: Are they mainly teams or mainly platforms for an individual leader (personalized-centralized parties) or politicians (personalized-decentralized parties)?

An Empirical Look: The Personalization of Politics and Political Parties

Returning to Krouwel (Reference Lijphart2012, 288), I am going to be silly and suggest a new party classification; the phenomenon of political personalization warrants it. Krouwel identified personalization as an important factor in the development of parties but he underestimated its magnitude. This made sense at the time he was writing, when the two major cross-national comparative attempts to map and measure personalization (which he quoted) announced skeptical and mixed findings (Adam and Maier Reference Adam, Maier and Salmon2010; Karvonen Reference Katz, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2010).

A decade passed, and skepticism has been replaced by a solid understanding that political personalization occurs in democracies and influences numerous arenas. New evidence has been added to existing data on the presidentialization of parliamentary regimes (Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke, Webb, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2005a) and on personalization in the media coverage of politics (Adam and Maier Reference Adam, Maier and Salmon2010; Karvonen Reference Katz, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2010).Footnote 4 It includes research on the personalization of electoral systems (Renwick and Pilet Reference Samuels2016), the growing presidentialization of parliamentary regimes (Poguntke and Webb 2018), the personalization of electoral behavior in terms of the personal vote (Renwick and Pilet Reference Samuels and Shugart2018), and the impact of leaders’ evaluation on voters’ behavior (Ferreira da Silva and Costa Reference Ferreira da Silva and Costa2019; Ferreira da Silva, Garzia, and De Angelis Reference Freidenberg, Levitsky, Helmke and Levitsky2021; Garzia, Ferreira da Silva, and De Angelis Reference Gauja2022; but see Bittner Reference Blondel and Thiébault2018). It is now apparent that political personalization occurs in many established democracies and is expressed in institutional changes, the media, and in the behavior of both politicians and voters (Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018).

Scholars also identified the personalization of political parties (Blondel and Thiébault Reference Bolleyer2010; Katz Reference Katz and Mair2019; Passarelli Reference Pedersen and Rahat2015; Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018; Schumacher and Giger Reference Shapiro2017; Webb, Poguntke, and Kolodny Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2012): that is, a decrease in the “partyness of government” in favor of a more personalized approach (Katz Reference Katz and Mair2018); personalization in leader selection (Cross and Pilet Reference Duverger2015; Musella 2015) and candidate selection (Hazan and Rahat Reference Hopkin and Paolucci2010); and a process of internal disintermediation, in which collegial party institutions dwindled while the rights and roles of party leaders expanded (Pizzimenti, Calossi, and Cicchi Reference Poguntke, Scarrow and Webb2022). This personalization occurred not only in new parties but also in veteran ones (Musella 2015). This process might be interpreted as an adaptation to new institutional, media, and cultural realities; as the flip side of party decline (Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018); or as the presidentialization of what Poguntke and Webb (Reference Rahat and Kenig2005b, 9) call “the party face,” which implies “a shift in intra-party power to the benefit of the leader.”

New parties were established as personalized-centralized entities (Musella 2015). These include the radical and populist parties of the Right that were founded with an emphasis on their leader. In contrast, most Green parties, with their individualized perceptions, were established as personalized-decentralized entities, seeing each supporter as an autonomous unit. In some countries, like Italy and Israel, even new parties that do not fit these relatively young and successful party families—like the Italian Five Star Movement and the Israeli centrist Yesh Atid—adopted personalized features (Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018). The trend was seen not only in Western Europe and established democracies but also in Central and Eastern Europe (Hloušek Reference Hloušek2015) and Latin America (Kostadinova and Levitt Reference Levitt and Kostadinova2014; Levitt and Kostadinova Reference Luna, Rodrıguez, Rosenblatt and Vommaro2014). Indeed, it characterized many Latin American parties long before personalization emerged elsewhere in the world. Those parties competed within a culture with strong personalismo (linked to centralized personalism) and clientelismo (linked to decentralized personalism) and in the framework of presidential regimes (Samuels and Shugart Reference Schumacher and Giger2010; Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002). The personalized characteristics of parties in some parts of the world, together with the personalization of existing parties and the addition of new personalized parties, implies that today personalized parties cannot and should not be seen as anecdotal, temporary, or marginal party types.

Although a process of political personalization is evident within and beyond parties, its strength varies greatly among countries and parties (Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018). In some cases, parties are still largely collegial entities; others are all or mostly all about their leaders (personalized-centralized); still others are just loose set of connections of individuals (personalized-decentralized). In most cases, parties fall somewhere in between these types.

A Theoretical Look at Partisan and Personalized Politics

Political scientists usually view politics as if parties, as collegial entities, are the main actors. Indeed, parties do run as such in elections and win all or most of the seats in legislatures. They are not only formal and legal entities but are also important in allocating public finances or, following elections, parliamentary and government positions. But internally, the balance of power in parties substantially differs between their leader, the party as a group, and the individuals who compose them.

Political parties exist because politicians find them to be useful to promote their individual goals in terms of policy, office, and votes (Strøm Reference van Haute and Gauja1990). Parties succeed to the extent that they fulfill two basic rationales: (1) as mechanisms for the coordination of the behavior of politicians and (2) as shortcuts for voters (Aldrich Reference Aldrich2011). Yet, dominant leaders (personalized-centralized politics) have the ability to rally their troops just as well as can collegial party institutions. Personalized-decentralized politics will likely lead to problems of coordination (Kölln Reference Krouwel2015); still, these issues may be manageable, if sometimes inefficiently handled, as the US experience tells us or as Carty’s (Reference Cohen, Karol, Noel and Zaller2004) stratarchical model suggests. Party leaders (centralized-personalized politics) and candidates (decentralized-personalized politics) can also serve as shortcuts for voters (Katz Reference Katz and Mair2018; Garzia, da Silva, and De Angelis, Reference Garzia, da Silva and De Angelis2022).

Political parties can also be understood in terms of their functions: the provision of political identity, political communication, policy formulation, the structuring of government, political mobilization, and political recruitment. However, politicians can and do fulfill these functions as individuals too: leaders, for instance, are crucial to voting and turnout (Ferreira da Silva, Garzia, and De Angelis Reference Freidenberg, Levitsky, Helmke and Levitsky2021). Politicians are now able to communicate directly with voters through social media. Governments may be structured more in line with the wishes of the leader (Poguntke and Webb Reference Poguntke, Webb, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2005a and b) or as a collection of individuals who are “bought” in return for government posts (Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018). Policy may be formulated by a dominant strong leader (personalized-centralized politics) or by individuals in office (personalized-decentralized politics). Finally, political recruitment may be a matter of self-selection and self-promotion from diverse dimensions of public life (the media, the business elite, nonpartisan, or opportunistic political backgrounds), without the need to spend time in the party ranks waiting patiently for one’s “turn.” Thus, all these functions can be handled by individuals, even if less efficiently (Kölln Reference Krouwel2015).

Whether we are assessing party decline or party adaptation, the collegial component has clearly weakened, and thus a new classification is needed that includes the personalized element. A developing research literature is exploring personalized politics in the institutional arena (Pedersen and Rahat Reference Pilet and Cross2021), specifically in nongovernmental institutions such as parties (Rahat and Kenig Reference Renwick and Pilet2018).

Existing Typologies and Personalized Parties

Although several party scholars have identified personalized elements within political parties, they either gave the matter insufficient attention in their classifications and typologies, did not relate to personalization at all, or developed a model to depict it but kept it separate from their main scheme.

As early as the 1950s, the heyday of the mass party, Duverger (Reference Duverger1965, 168) observed that parties had experienced an “increase in the authority of the leaders and the tendency towards personal forms of authority” since the early twentieth century. He even used the term “personalization,” though he largely ignored it in his well-known typology (or rather typologies). For Katz and Mair (Reference Katz and Mair1995, Reference Kefford and McDonnell2009), the burgeoning prominence of the leader (or party leadership, which may be singular or plural) was just one element in the evolution of parties that focused on the changing relationships between party, society, and the state and on the “three faces” of the party. Although Webb, Poguntke and Kolodny (Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2012, 77) identified a “very definite tendency of more recent models to emphasize leadership autonomy,” scholars did not see this as a main feature of their models.

Panebianco (Reference Pasquino1988, 264) noted (while spelling out five differences in two-party models) that the mass-bureaucratic party (prominent in the 1950s–60s) was characterized by the “pre‐eminence of internal leaders, collegial leadership,” whereas the electoral-professional party that emerged later was marked by the “pre‐eminence of the public representatives, personalized leadership.” But this distinction was not presented as the salient theme that differentiated these parties from others. He even proposed a separate ideal type of a personalized party, the charismatic party (similar to the “personal party” described here), but this was a “stepson” of his typology and was not directly compared with the other ideal types. Interestingly, Panebianco (171–73) came close to the logic of the proposed classification in describing party organization as reflecting “three types of dominant coalitions” that differ in vertical terms of power centralization and decentralization. In other words, although all the ingredients for a new typology were there, Panebianco did not integrate them into a cohesive scheme.

Building on previous classifications, Gunther and Diamond (Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003) devised a comprehensive typology comprising 15 party types. The personalized aspect, however, was marginal; only one type referenced a personal party. Indeed, they presented “the internal dynamics of party decision making, particularly the nature and degree of prominence of the party’s leader, ranging from a dominant charismatic figure, at one extreme, to more collective forms of party leadership, at the other” as one of two additions to their two main dimensions for differentiating between parties (171–72). In my proposed classification, by contrast, the personal aspect is key—and not exclusively in reference to the leader but also to politicians, in the plural.

Other recent typologies do not have the personalized element as a core theme. Wolinetz (Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002), for example, suggested a classification based on party goals: it differentiates among parties whose main goals are vote seeking, office seeking, and policy seeking. Bolleyer (Reference Bolleyer2011) focused on territorial centralization and decentralization of the party organization. Were we to pit her classification against mine, it would be hard to determine which points to a more important facet of power dispersion and concentration. Both classifications have historical roots in an era that was more parochial and also more personal. Both are once again highly relevant, because of globalization and personalization. This suggests these typologies might be better seen not as competitors but as capturing two different dimensions: vertical and horizontal. They may serve two different research goals but can be integrated, like Lijphart’s (Reference MacDonnell, Vampa, Heinisch and Mazzoleni2012) political-parties-executive dimension and federal and unitary dimension. Such integration is beyond the scope of this article but seems to be the more constructive path.

This low level of attention to the personalized element is understandable, and it is not surprising that Krouwel (Reference Lijphart2012), who tried to integrate existing typologies, did not leave much room for it. When parties were built following the blueprint of the mass party, they were mostly collegial institutions: “a distinctive feature of political parties has been its corporate character; that is, the fact that its existence depended on the collective nature of its organization” (Calise Reference Carty2015, 303). But as of 2015, “after sharing, through its various steps of evolution, the form and status of a corporate body, the party organization is falling prey to the virus of personalization, that is invading so many realms of contemporary life” (304). And yet “personal parties are not alone on the scene of democratic politics, with traditional parties still playing an important and often decisive role” (312–13). This underscores the need for a classification that will include not only the new personalized types but also the older collegial type.

The marginalization of personalized elements is even more understandable when one looks at the literature on party institutionalization. Some scholars perceive personalization as antithetical to institutionalization or as creating an obstacle to it. Others suggest that personalized parties may be institutionalized under specific conditions; yet such a development is usually interpreted to imply the depersonalization of the party (Bolleyer Reference Calise2013; Harmel and Svåsand Reference Hazan and Rahat1993; Mainwaring and Zoco Reference Michels2007; Panebianco Reference Pasquino1988; Pedahzur and Brichta Reference Petrova2002). Thus, until recently, creating a classification with the personalized element as a major theme, with the same weight as the collegial one, could have been seen as a waste of time, as investing in characterizing parties that may have short lives, or, worse, as emphasizing an aspect that is nonpartisan or antipartisan by its very nature.

Proposed Personalized Party Types

Some attempts have been made recently to respond to the new personalized reality. Most have not offered a comprehensive classification or typology but have suggested adding a new model or models to meet this need.

In the 1990s, Hopkin and Paolucci (Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone, Heinisch and Mazzoleni1999) identified a new party type, the business firm model. Although they did not spotlight its personalized nature, they did recognize the centrality of a specific individual for its establishment and survival. But the model was too detailed to cover the universe of personal parties, and they did not locate it within established typologies. It was too early then, it seems, to see the full implications of political personalization. Personalized parties still looked like an anomaly, unlikely to have a central role on the political stage; on the contrary, it was expected they would fizzle out. Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, the inspiration for the business firm model, still looked idiosyncratic. Only later would the Italian party system become personalized across the spectrum (Pasquino Reference Pedahzur and Brichta2014). Calise (Reference Carty2015) did propose a typology of personalized parties, but it was neatly tailored to developments in Italian politics and could not be applied elsewhere; moreover, it only dealt with the personalized-centralized type and did not include parties with collegial features. Kefford and McDonnell (Reference Kirchheimer, LaPalombara and Werner2018) took a broader approach when they compared the two personal parties of Berlusconi in Italy and Clive Palmer in Australia. They issued certain useful propositions but did not integrate their model within a full-fledged typology.

Kostadinova and Levitt (Reference Levitt and Kostadinova2014) did offer a more comprehensive typology incorporating both personalized and nonpersonalized party types. It assessed two elements: the party’s organizational capacity and its identification with the leader. This classification was developed around the status of the leader (centralized personalism) and included nonpersonalized parties (which they labeled “institutionalized parties”) but did not address the possibility of a personalized-decentralized intraparty order.

The Need for a New Classification: Personalization and Beyond

Katz (Reference Katz and Mair2018) claimed that personalization poses serious challenges to party democracy (see also Cross, Katz, and Pruysers Reference Cross and Pilet2018). Years earlier, when pondering a research agenda, he and Mair (Katz and Mair Reference Kefford and McDonnell2009, 761) asked, “If nothing much remains to mediate relations between the voter and the voted, should we continue to think of the party as an organization at all?” Luna and coauthors (Reference Mainwaring and Zoco2021) suggest differentiating between parties and mere electoral vehicles. Here I stick to the good old minimalist definition of a political party—an organization that presents candidates for public positions—and differentiate parties in terms of the power balance within them, between their leader, their politicians, and the party as a team.

Integrating personalized elements into a classification of parties seems to counteract the raison d’être of political parties, which is to be an organization for collective action (Aldrich Reference Aldrich2011). Yet, when answering the question, “what is a political party?” party scholars explicitly, in most cases, related to two types of actors, the individual and the collective.

All answers included the collective element, using various words to describe it: “a body of men united” (Burke in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6), “a group of persons” (Duverger, Reference Ferreira da Silva and Costa2020), “a coalition of men” (Downs in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6), “a ‘group’” (V. O. Key in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6), “a relatively durable social formation” (Chambers in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6), “group” (Epstein and Schlesinger in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6; Sartori Reference Schumacher, de Vries and Vis1976, 63), “coalitions of elites” (Aldrich in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6), and “a free association of individuals” (Venice Commission Reference Ware, Katz and Crotty2020, 21). Thus, the party, which is a part of a whole (Sartori Reference Schumacher, de Vries and Vis1976), is also an aggregate of individuals.

The answers differ, however, when it comes to the nature of the aggregated unit, whether it is simply an aggregate of generic individuals (of “men” according to Burke and Downs in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6, or “persons” according to Duverger Reference Ferreira da Silva and Costa2020), individuals with specific characteristics (“persons who regard themselves as party members” or a “group of more or less professional workers,” according to V. O. Key in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6) or of groupings (“coalitions of elites,” as per Aldrich in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6). Others do not say who the members of the groupings are but mention individuals who are either leaders (Chambers in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6) or who seek to win public office (Epstein and Schlesinger in White Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006, 6; Sartori Reference Schumacher, de Vries and Vis1976, 63). In a fuller definition, the Venice Commission (Reference Ware, Katz and Crotty2020, 21) suggests that the aim of these individuals is “to express the political will of the people” and that their means are “the presentation of candidates in elections.”

The classification presented here asks the question, “An aggregate of what?” A party may be an aggregate of a single prominent individual and a group of her adherents (centralized personalism); or of a group that, as such, is greater than the sum of its individual components (collegial); or of autonomous individuals in plural (decentralized personalism). In taking this approach, it touches on a neglected element in the definition of political parties and allows for answers that reflect variance in the basic rationale of the organization of parties.

Two decades ago, Gunther and Diamond (Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003, 168) introduced a new typology because “many of the parties that first emerged in the late twentieth century have prominent features that cannot be captured using classic party typologies developed a century earlier.” As demonstrated, none of the existing typologies gives sufficient consideration to the impact of personalization on new and old parties. But even if the immediate motivation is to answer the needs of party scholarship in the age of political personalization, the classification proposed here is more than an update. It offers an approach that will be more resistant to changes over time and differences in location because it directly touches the core issue of political power and the meaning of the political party.

The Classification: Personalized-Centralized, Collegial, and Personalized-Decentralized Parties

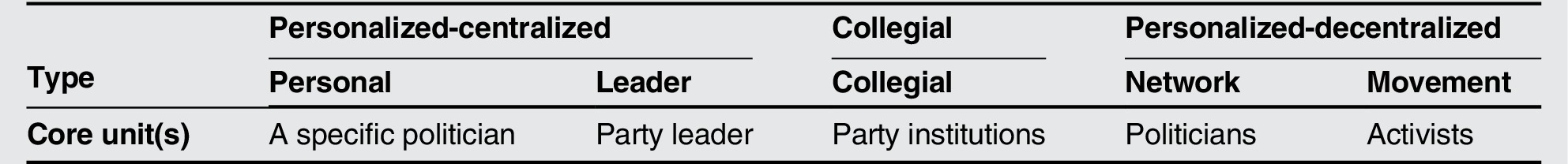

The proposed types have three organizational patterns: (1) personalized-centralized parties that are all or largely about their leaders, (2) collegial parties that are based mainly on collective decision making and authority, and (3) personalized-decentralized parties that are mostly a collection of autonomous individuals (table 1, first row).Footnote 5 I locate these party types on a continuum with five milestones or yardsticks (second row). First, note that some of these labels were used by other scholars, but they do not necessarily share the same characteristics. Second, the classification is presented as a continuum for the sake of simplicity. If parties possess only characteristics of one of the proposed types or a combination of neighboring types, then the continuum holds up. However, if a party has a combination of all three characteristics, a triangular-shaped perception or a factorial approach might be more useful.Footnote 6

Table 1 Party Types: Core Unit(S)

One end of the spectrum, where power is diffused, represents a party in which many individuals have more or less equal power. But this is not about all individuals. Even in a very open and participatory party, people need to act to influence others, and most people at most times—even party members—will be passive (van Haute and Gauja Reference Vittori2015). I thus label those who are active as “party activists” (Schumacher, de Vries, and Vis Reference Strøm2013). At the other end of the spectrum, where power is concentrated, the party is absolutely dominated by a single individual: the party leader. In the middle we find the collegial party; there, major decisions are made by party institutions (e.g., conventions, central committees, executive committees). Because such group decision making is about building and rebuilding majorities or consensus, not about the power of many individuals or of one, this type is in the middle. Two party types are located between each pole and the middle (leader and network), on each side of the spectrum, giving room for intermediate options.

Personalized-Centralized Parties

Leaders dominate personalized-centralized parties. They hold more roles, authority, and powers than all other intraparty actors, be they party collegial institutions or other politicians. The classification proposes two types: (1) the extremely personalized personal party, whose leader is its creator and “owns” it, and (2) a less personalized party type, in which the leader is dominant due to the virtue of her position; the party she leads is the creator of her dominance.Footnote 7

The Personal Party: Le parti, c’est moi

The personal party “belongs” to one person. It is not an impersonal subsystem run by people in their capacity as holders of specific positions. Instead it is a party whose “only rationale is to provide a vehicle for the leader to win an election and exercise power” (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003, 187; emphasis in original). In Weberian terms, it is based solely on charismatic authority (though charisma is reflected less in transcendental terms and is based more on the leader being the sole source of popular support for the party). The leader dominates everything, from candidate selection to policy decisions, from deciding if and when to join—or leave—a governing coalition to who will serve and in what role. Berlusconi’s Forza Italia is a well-known exemplar here. Such parties rarely outlive their leaders unless they change their type. As with Panebianco’s (Reference Pasquino1988) charismatic party, the organizational glue is loyalty to the leader. Because it is “weakly institutionalized by design” (Kostadinova and Levitt Reference Levitt and Kostadinova2014, 500; see also Kefford and McDonnell Reference Kirchheimer, LaPalombara and Werner2018; Panebianco Reference Pasquino1988), its institutions cannot counterweigh the leader.

The Leader Party: Personalized, but Legal-Rational

In this case, one individual holds the dominant status simply by winning the party leadership. The position gives her extensive roles, authority, and powers. She influences candidate selection, the nomination of ministers and parliamentary positions, policy formation, intraparty agenda setting, and more. In Weberian terms, her main source of authority is legal-rational (unlike the personal party). The party constitution and regulations are the foundation of her authority and a potential source of constraint on it. Once she leaves the position, someone else will assume all her roles, powers, and authority.

The Collegial Party: We, Us, Them

Intraparty institutions run the collegial party. They may be small and exclusive institutions (management, national executive committee, bureau) or large and more inclusive (central committee, convention, assembly). In Weberian terms, the main source of their authority is legal-rational (or, as Blondel and Thiébault Reference Bolleyer2010 call it, bureaucratic-legalistic). Unlike the leader party, the collegial party belongs to an impersonal collective. The leader is first among equals.

Kostadinova and Levitt (Reference Levitt and Kostadinova2014) developed an ideal type against which their personalized-centralized party types were compared and called it the “institutionalized political party.” They characterized this type in a way that perfectly matches the status of the leader in what I call the collegial party: “Alternation of power at the helm of the party is genuinely possible at periodic intervals. Even if parties, particularly in parliamentary systems, choose to keep or change leaders for strategic reasons, the leaders nonetheless serve the party and not vice versa (503).”

Although the collegial element seems to have long been a generic feature of parties (Calise Reference Carty2015), the traditional mass parties, with their multiple institutions at various levels (national, regional, and local), are the most fitting real-world expressions of this type. But many others that were transformed from being mass parties or were established as different types (catch-all, cartel parties, etc.) may exhibit at least some elements that characterize collegial parties.

Personalized-Decentralized Parties

The personalization of parties involves not only their leaders but also party politicians (decentralized personalization). As Ignazi (Reference Karvonen2017, 162) puts it, “Personalization does not concern the top leadership only. It flows throughout the party.… Whoever holds a position in the party or in the elected assemblies, at whichever level, points to himself or herself as apart from the party structure.” With the internet and especially social media now an everyday part of politics, this type of party has greater opportunities to develop and thrive.

This category contains two subtypes that differ in their organizational patterns: the network party and the movement party. Both are based on webs of relationships between individuals, rather than on a hierarchal organization with defined functions and boundaries for each of its levels and parts; both have “loose networks of grassroots support with little formal structure, hierarchy and central control” (Kitschelt Reference Kölln1989, 66). The most important difference between them is that the personalized core unit of the network party is the politician, whereas for the movement party it is any individual who is active in party life (table 1).

The Network Party: We Are All Politicians

The network party is based on a web of linkages between individual politicians. In Weberian terms, the main sources (plural) of authority are charismatic (in the broad sense). Each politician has her own power base and personal organization (the campaign machine, clientelistic network, and, in the case of incumbents, support staff). The party is a loose confederacy of personalized organizations that work together under the same banner. Once the intraparty nomination process is complete, politicians do not usually compete with each other for the same position, and they use the same party label. Beyond this, each of them is quite autonomous.

Political parties were first formed when representatives (elected by exclusive electorates), whose identity was mostly local, met in parliament and realized that building permanent coalitions was an efficient and effective way to promote values and interests. It is thus no coincidence that the “elite party” of the nineteenth century (Katz and Mair Reference Katz and Mair1995, 18) had features of a network party. It was centered around its politicians, and its basic units were their local electoral machines. Aldrich’s (Reference Aldrich2011, 306) description of the contemporary American political party fits here: “a party designed around the ambitions of effectively autonomous politicians, responsible for their own electoral fates and therefore responsive to the concerns of their individual constituencies.” Indeed, the US Democratic and Republican Parties can be described as networks of thousands of candidates and politicians who compete for and hold public positions at the federal, state, county, and local levels.Footnote 8

The Movement Party: We Are All Individuals

The movement party is a postmaterialist entity that is very much about individualism.Footnote 9

It thus does not fit any of Weber’s sources of authority. The ideal definition of its core unit would have been any individual supporter of the party, but here it is adapted to “real life” by limiting it to activists. They, not any collegial intraparty body or the party leader, are the source of authority. The movement party resembles the model of “pluralist democracy” (Katz Reference Katz1987; Kölln Reference Krouwel2015), in which the individual rather than the party comprises the core unit and politics is conducted on the basis of building and rebuilding ad-hoc agreements. The rules concerning leadership, such as rotation and collective leadership, intend, together with empowering the grassroots level, to counter Michels’s (Reference Panebianco1962) iron law. The German Green Party, when established, was quite close to fulfilling this model (Poguntke Reference Poguntke and Webb1987). These ideals are still features of reforms that some parties adopt in the age of individualism and personalism (Gauja Reference Gunther and Diamond2018).

A Cross-Party Type Comparison: An Operationalization

A problem that is inherent in any move from a nominal classification to its operationalization—and is evident when considering party classifications and typologies—is the gap between the stated characteristics and what can actually be measured. This section proposes indicators to address this gap. They may be integrated in various ways (for example, by creating a combined index or several indices) and used for diverse purposes (synchronic or diachronic comparisons; single-country or cross-national studies). The proposed operationalization (and its implementation in the next section) should be seen as preliminary proof of the viability of this classification, as an example of a possible operationalization of it. In the real world, operationalizations strive to achieve an optimal balance between theory and empirical availability; scholars may select different paths to achieve this goal.

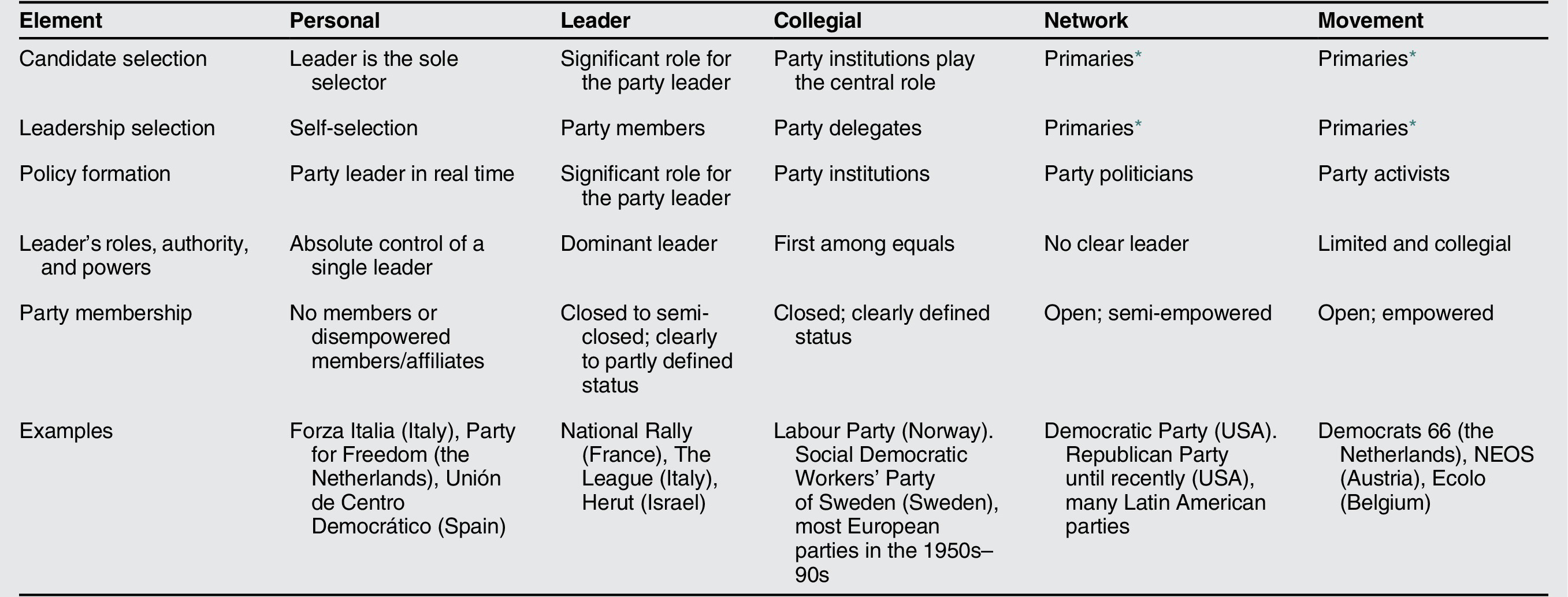

Table 2 presents elements of party organization that epitomize the logic of the classification and may thus serve as indicators for identifying party types in the real world. It relates, first, to three main events in intraparty life: leadership selection, candidate selection, and policy formation (Gauja Reference Gauja, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2017). Second, it focuses on the roles, authority, and powers of the leader. Finally, it looks at the nature of party membership and other types of party affiliations. The different party types share some characteristics, although each combination is unique, expressing a specific approach to party politics and creating differing incentives.

Table 2 Characteristics of the Five Ideal Types

* According to Kenig et al.’s (Reference Kitschelt2015, 152) definition: “Primaries are those selection methods in which the cumulative weight of influence of party members, supporters and/or voters is equal to or greater than all other more exclusive selectorate(s) combined.”

Candidate Selection

Parties almost always monopolize candidacies, and thus they play the role of gatekeepers to various elected positions. They differ, however, in the level of inclusiveness of their selectorates (Hazan and Rahat Reference Hopkin and Paolucci2010). In the personal party the leader is the sole selector; in the leader party the leader plays a role in candidate selection by screening candidates, directly nominating some of them, or by suggesting or vetoing candidacies. Delegates who make up party institutions are usually the selectors in collegial parties. Personalized-decentralized parties tend to use inclusive methods that enable any politician to be selected through the vote of her personal supporters (network party) or that give any member (and sometimes also affiliates) a say in the process (movement party).Footnote 10

Leadership Selection

The way the leader is selected dictates her relationship with the party. Parties again differ in the levels of inclusiveness of their selectorates (Pilet and Cross Reference Poguntke2014). The selection process for the personal party is clear-cut: the leader “selects” himself. The head of a leader party is selected through primaries, giving her an autonomous stance and a source of legitimacy vis-à-vis other intraparty actors. The leader of the collegial party, like its candidates, is selected at an assembly of party delegates who aim to keep him accountable to the party. In the network party, there is no clear party leader. In some cases, the one who is perceived as the leader may be selected for the most senior position. Like all other candidates, an inclusive selectorate (members, supporters) selects her. In a movement party, in the name of empowering the base, those at the grassroots are expected to influence leadership selection.Footnote 11

Policy Formation

In the personal party, there is no policy formation process beyond the reactions of the leader to specific issues in real time. In the leader party, the leader navigates and usually wins full support from his party, as long as he understands the limits of his relatively wide space for maneuver. With collegial parties, again, party institutions deliberate and decide. If, for candidate and leadership selection, the two personalized-decentralized types use similar mechanisms although for different reasons, in this case there is a big difference in their modus operandi. Politicians belong to the network party because they agree generally with its ideology; beyond that, each politician is a policy maker. They also serve, through trade-offs with other politicians, the interests of their constituency. The movement party sticks by its grassroots, which gets a say in policy formation.

The Leader’s Roles, Authority, and Powers

The party leader has absolute control of all roles, authority, and powers in the personal party and a high level of control in the leader party; moderate control in the collegial party, whose intraparty institutions try to keep her accountable; and limited control in both types of the personalized-decentralized party. The extent of control might be measured as the number (and significance) of potential roles and authority that the leader holds, such as convening and leading meetings of party institutions, deciding to enter a coalition, or controlling party resources (budget, staff).

In addition, in each party there are potentially several leadership roles that can be filled by several people or by just one.Footnote 12 In the personal party the leader alone holds all these positions, whereas in the leader party she holds most of them. The collegial party typically fills its leadership positions with different individuals. In the network party there is no clear leader but rather different people are perceived as fulfilling these roles. In the movement party, as an attempt to counter oligarchical trends, even a single role may be divided between different persons.

Party Membership (Including Other Types of Affiliation)

Party membership and other types of affiliation to parties differ substantially among party types.Footnote 13 The personal party has either no members, or it may have disempowered members or affiliates. Those involved are in the party because the leader wants them there; he recruits them, and he can also oust them. In the leader party the semi-empowered members are a separate source of legitimacy for the leader and enhance her autonomy vis-à-vis party institutions. The collegial party has a more definitive status of membership, with minimal obligations (paying dues, for example) and distinct but limited rights (selecting delegates for party institutions or candidate selection bodies). The network party will take anyone who can be bothered to get involved in selecting and electing but offers nothing beyond these functions. The movement party will take anyone who is willing to get involved in anything the party does and will try to empower them.

The New Classification in the “Real World”

To demonstrate the validity and usefulness of the proposed classification, this section identifies cases in several countries that are close in their features to the proposed pure types. It also picks some interesting in-between cases and demonstrates how the classification is useful in analyzing them. But before diving into the “real world” some caveats are needed.

In examining the real world, we encounter two stories about parties. One is the official, formal story that is told through parties’ constitutions and regulations. The other is the “real” story, which might resemble the official one, might be totally different, but mostly lies somewhere in between. Sometimes no official story is available. The informal and untold stories are not randomly spread among party types but for several reasons are biased toward the collegial version. First, in many cases party laws dictate a collegial infrastructure. Second, the collegial type was the norm for decades, and even when parties changed, they added personalized features rather than eliminating their collegial attributes, at least on paper. The collegial structure served as a default for newer parties too. Only those that really invested in their organizational structure and functions wrote a new story. Some just replicated established parties’ constitutions and regulations that they never intended to follow. Finally, in some cases common social norms prevent parties from telling the real story when it is about a powerful leader in a country with a democratic political culture or when its organization revolves around patronage and clientelism. Thus, our expedition into the real world is not based solely on documented, largely official stories (PPDB Reference Renwick, Pilet, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2021) but also on academic case studies that look beyond them.

Take Silvio Berlusconi. He is the founding, sole, and undisputed leader of Forza Italia (1994–2009; 2013–) and People of Freedom (2009–13). He selected their candidates, or rather, because there were thousands of candidacies, he selected many and could veto any of them. Although his parties had members and affiliates, they were never empowered (Kefford and McDonnell Reference Kirchheimer, LaPalombara and Werner2018). The French Front National had similar characteristics in 1972–2011 under Jean-Marie Le Pen (Ivaldi and Lanzone Reference Katz and Katz2016), as did Alberto Fujimori’s numerous personal parties in 1990s Peru (Levitt and Kostadinova Reference Luna, Rodrıguez, Rosenblatt and Vommaro2014). The leader of the Dutch Party for Freedom, Geert Wilders, enjoys total control in a party in which he is the sole member (Mazzoleni and Voerman Reference Musella2017). To these better-known examples we can add many short-lived parties like the Australian Clive Palmer’s United Party (Kefford and McDonnell Reference Kirchheimer, LaPalombara and Werner2018) and the Spanish Unión de Centro Democrático (Hopkin and Paolucci Reference Ivaldi, Lanzone, Heinisch and Mazzoleni1999). This phenomenon is more typical of the Right, especially the populist and extreme parties, although examples of personal Center and Center-Left parties can be found in Israel (PPDB Reference Renwick, Pilet, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2021), Italy (Calise Reference Carty2015; Pasquino Reference Pedahzur and Brichta2014), Bulgaria, and Peru (Levitt and Kostadinova Reference Luna, Rodrıguez, Rosenblatt and Vommaro2014).

As elaborated earlier, databases that focus on the official story, like PPDB (where such parties are characterized by a lot of “no data” and “not applicable” values), are not ideal sources to identify this party type. One way to create a list of parties that are likely to be personal is to consult the V-Dem (2021) database on political parties, specifically the two questions that ask about candidate selection and party personalization. Most probably, parties in which the leader is perceived by the coders as the sole selector and as emphasizing the personal will and priorities of one individual party leader also display the other characteristics that are proposed here (38 parties met these criteria).

Leader parties sometimes originate from a transformation of a personal party, as was the case with the French National Front, when Marine Le Pen replaced her father as party leader through primaries (Ivaldi and Lanzone Reference Katz and Katz2016). Although only time will tell whether this development was really about democratization of the party—that changed its name to National Rally—it was certainly a move toward its institutionalization. The Italian Lega Nord (later renamed the Lega) is another example of a party that was closer to the personalized type under its first leader (Umberto Bosi) but became a leader party with the new leaders, Roberto Marone and Matteo Salvini (MacDonnell and Vampa Reference Mazzoleni and Voerman2016). The Israeli Herut party (1949–88) and later Likud (1988–) are also examples of a leader party (Shapiro Reference Dem1991). Yet throughout their history there were times in which they displayed some characteristics of a collegial party and others (more recently) when they moved toward the personal party model. Some collegial parties morph into leader parties under the influence of charismatic leaders. The Hungarian Fidesz started out with a collegial platform but was transformed over the years into a leader party (Biezen Reference Bittner, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2005; Hloušek Reference Hloušek2015); in recent years, it has taken on more and more personalized features.

The personalization of politics has reduced the numbers of parties that are purely collegial. A survey of veteran European parties (PPDB Reference Renwick, Pilet, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2021) reveals that most have a collegial platform with some personalized features. Some, especially Conservative, Christian Democrat, and Liberal parties that compete with populist and Far Right rivals, added centralized-personalized features that enhanced the powers of their leaders; others, especially, Social Democratic parties, which compete with Green rivals, added decentralized-personalized features that empowered their members. The parties that almost totally preserved their collegial features (with some nuances) are the Norwegian and Swedish parties (PPDB Reference Renwick, Pilet, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2021). Their main functions—selection, policy formation, and additional decision making—are continuously performed by their collegial party institutions, involving members in party decisions only or predominantly through delegates.

Following Samuels and Shugart’s (Reference Schumacher and Giger2010) research on parties in presidential and parliamentary systems, the expectation is to find network parties in presidential democracies. Both US parties adhere to this subtype, although the Republicans “under” Trump seem to have adopted some features of a personalized party (for example, Trump’s explicit involvement in candidate selection and his dominance in policy formation). The same is true for many parties in Latin America, though the more relevant organizations are informal, based on personalized networks of patronage headed by local and regional bosses who themselves compete with or support “their” candidates (Freidenberg and Levitsky Reference Garzia, da Silva and De Angelis2006). As Petrova (Reference Pizzimenti, Calossi and Cicchi2020, 4) puts it, “Activity seems to lie on the shoulders of individual politicians able to mobilize voters and resources during electoral periods.” Thus, the proposed classification, with its focus on personalism versus collegialism, allows us to integrate both US political parties—which had been called exceptional because they did not fit existing typologies (Ware Reference White, Crotty and Katz2006)—and the loosely (or differently) organized Latin American parties in a universal cross-national classification.

The characteristics attributed to movement parties were not only found, as could be expected, in many Green parties but also in some liberal parties like the Dutch Democrats 66 and the Austrian NEOS. The Belgian Ecolo was the purist example. with collective leadership and empowered members who select their co-leaders and candidates and influence party policy through open congresses and referendums (PPDB Reference Renwick, Pilet, Cross, Katz and Pruysers2021).

Some party transformations that imply movement from one type to another were mentioned earlier. The characteristics seen in most parties put them somewhere in between the proposed pure types. There is one combination, however, that is relatively rare but fascinating: it combines centralized and decentralized personalized elements and avoids, as far as possible, collegial features. It is seen in a number of important parties that became ruling parties, like the Italian Five Star, the French En Marche, the Israeli Kadima, and seemingly also the Spanish Podemos. These parties had empowered leaders, relatively empowered members, and weak party institutions. This combination could be labeled “plebiscitarian” (Vittori Reference Webb, Poguntke, Kolodny and Helms2021) and may substantiate the claim that the classification is not about a continuum but a power triangle between individuals, the group, and the leader.

Advantages and Limitations of the Proposed Classification

Two justifications for the new classification, as discussed earlier, are the absence of a classification that can capture party types in the age of political personalization and that this proposed classification is more than just an update, because it covers the core issues of political power and the rationale for the very existence of political parties. The examination of the proposed classification below is based on several criteria: simplicity and parsimony, universalism, usefulness, and time resistance. This is not a call to abandon earlier typologies nor is it an attempt to claim this new one’s superiority, in all its aspects, but to humbly make the case for its inclusion in a respected family.

Simplicity and Parsimony

Party typologies and classifications vary in their simplicity. For example, Gunther and Diamond use 3 criteria and propose 15 party types, whereas Wolinetz (Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002) proposes a single criterion and 3 party types. Complex and broad typologies, for instance, may be claimed to reflect more variance and to allow more room for variables that affect the nature of a party (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003). But they may also be criticized because “a profusion of categories can confuse as well as clarify” (Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002, 137). Indeed, there is always a trade-off between simplicity and complexity, conciseness and richness.

My classification is relatively simple. It is based on a single comparable criterion and comprises five party types that can be identified using standard criteria. That single criterion is the power balance between the personal (with its two types) and the collegial. Yet it does not “fall victim to reductionist argumentation” because it presents “a careful assessment of relevant evidence” attesting to its “paramount importance” (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003, 170). By their very nature, typologies and classifications “privilege” criteria, whether one, two, or more; any typology or classification should come with a warning sign about that. The merit in offering a single criterion is that it enables later enrichment of the classification if there is a strong correlation between the proposed criterion and other criteria (for example, ideological tendency). In contrast, if the basic platform is rich in detail, it creates a non-inclusive and non-universal typology from the outset or because new innovations will develop sooner or later.

Although my classification is simple and parsimonious, it offers a complete, inclusive, yet not too demanding universe, with space for all parties—not just those that fit the specific categories. This space can be stretched to include combinations with different amounts of collegialism and personalism and can be easily turned into a continuum or even a two-dimensional space. Simplicity and parsimony boost the chances that the proposed classification will travel more easily through time and space and will be suitable for operationalization, as elaborated next.

Universalism

Gunther and Diamond (Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003, 190) argue that “for a typology of parties to be useful for broad, cross-regional comparative analysis it must allow for the emergence of distinct types in greatly different kinds of social contexts.” The ingredients of the proposed classification are universal: individuals and groups, power, and problems of collective actions. Moreover, the classification is about party organization, with no ideological flavor, no pro- or antidemocratic orientation, and no necessary linkage to a certain era or to external elements in the political, social, cultural, or technological environment in which the party operates.

Underscoring the universal distinction between the personalized and the collegial elements serves as a remedy for the West European bias of several existing typologies (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003; Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002). Many parties from other parts of the world, which operate within different political cultures and institutional contexts (on presidentialism, for example, see Passarelli Reference Pedersen and Rahat2015; Samuels Reference Sartori2002; Samuels and Shugart Reference Schumacher and Giger2010), never experienced the collegial blueprint of the mass party. This classification gives much more room than previous ones to the less collegial, more personalized party types that can be found in these countries.Footnote 14

Time Resistance

Party typologies sometimes do not hold up when substantial changes take place (Wolinetz Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002). The classification here is more resistant to changes over time because it is focused on the basics: on power and on the core rationale for the existence of parties (in terms of collective action). This eliminates the need to develop new party types each time a seemingly innovative type comes into the world, nor will there be a need for “concept stretching” (Gunther and Diamond Reference Harmel and Svåsand2003). This claim can be partly validated by looking at the evolution of political parties. We can tell the story of the creation and solidification of parties, showing how they became more collegial with time. New chapters have been added in recent decades, indicating a sharp turn of direction toward the personalization of existing parties and the emergence of new personalized parties.

Usefulness

Wolinetz (Reference Wolinetz, Gunther, Montero and Linz2002, 149) argued that a party typology or classification should “reflect questions we are interested in.… [T]here is no one universally valid scheme, but rather that the utility of a schema depends in part on what we want to know and … a classification useful for one purpose may not be useful for another.” Usefulness is an important criterion because typologies are created to be applied, and not to be locked away in a drawer. Wolinetz continued, “The utility of such a scheme depends on our ability to find indicators for key terms or orientations and the degree to which we can use these to pose and test hypotheses about what difference this makes” (153).

The proposed classification, unlike some other schemes, allows users to operationalize in-between cases and combinations because it has a clear continuous or spatial logic. Moreover, although it was constructed to be synchronic and respond to current developments, it can be used diachronically to map changes. Finally, the possibility of developing such measurements allows users to include party types as a variable in complex large-n analyses aimed at answering substantive questions on issues like political personalism and personalization in general, populism, and representation. Again, all these advantages are apparent within the limits of the questions asked and the potential answers that can be given.

Limitations

The focus on a single criterion is not only an advantage but also relates to a main limitation of the classification. To look beyond the decentralized-centralized, personalized-collegial divide, one has to add elements from other classifications (e.g., Bolleyer, Reference Bolleyer2011, as noted earlier). Another limitation pertains to its relationship with the real world. It was demonstrated that it is possible to find cases that fall within and between the proposed types. Yet only more dialogue with the real world, which is beyond the scope of this study, would enable the design of an optimal operationalization that is viable, reliable, and valid for use in a large-n study, facilitating the new databases that are available today.Footnote 15

Conclusion: The Future of Parties in the Age of Personalism

We have witnessed both political depersonalization and personalization in established democracies. The personalized polities of the nineteenth century (and within them personalized parties) were transformed into depersonalized polities with collegial parties. In recent decades, a reverse wave began, and personalized politics returned with personalized parties, though in a different form from the past. This implies that “collegial” is not a constant in the nature of the party but exists in balance, to varying degrees, with the personalized component. This realization could open fruitful paths of research. One path could focus on parties and further examine the linkage between party type and ideology, age, or size; another path might explore the consequences of party types: their influence on politicians (e.g., on party cohesion and unity) or voter behavior (e.g., the weight of the evaluations of the leader, the party, and the candidate on the vote, etc.), how they are covered by the media, and much more. Furthermore, future studies can use the proposed differentiation as one of several causes or consequences for the general phenomena of personalization, populism, or democratic backsliding.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the ISARELI SCIENCE FOUNDATION (Grant no. 1835/19). I would like to thank Noam Gidron, Reuven Hazan, Ofer Kenig, Helene Helboe Pedersen, and the four anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.