Introduction

The arrival of the Troika (comprising the International Monetary Fund, the European CommissionFootnote 1 and the European Central Bank [ECB]) in the capitals of Greece, and then Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus, provided some of the most dramatic moments of the Eurozone crisis. With financial markets demanding prohibitive rates to purchase their bonds, and following pressure from the European Central Bank to accept a bailout, these nations were forced to accept external assistance in order to finance their budget deficits, which had in most cases arisen following the financial crisis of 2007/8. Ireland's bailout, which ran for a three-year period from December 2010, was dependent on undertaking fiscal consolidation and structural reforms as outlined in the Memorandum of Understanding agreed with the Troika.

While the European Union had, in the pre-crisis period, focused on crisis prevention, in the form of the Stability and Growth Pact which set limits on debt and deficits, it had not set up a similar architecture to deal with crisis management (Pisani-Ferry, Reference Pisani-Ferry2013). The Troika was a child of circumstance, borne of the need of European politicians to deal with the crisis that engulfed Greece in early 2010 (Pisani-Ferry, Reference Pisani-Ferry2013). It was the arrival of the IMF, in particular, that was most feared, and not only in Ireland. But did the three organisations operate in concert, or did they have different priorities?

The extent and nature of conditionality imposed by the Troika (see, for example, Featherstone, Reference Featherstone2015) have been key themes in emerging literature on the Eurozone crisis. Petmesidou and Glatzer (Reference Petmesidou and Glatzer2015: 165) point to the ‘strict and binding conditions for the bailed-out countries’, while Theodoropoulou (2015) notes the very high degree of specificity of fiscal and structural reforms itemised in the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by Greece and Portugal. An initial question for this paper, then, is the extent to which the cuts that were implemented in Ireland arose from the MoU that was agreed with the Troika in 2010.

A second key theme that emerges from this literature concerns the room for manoeuvre of national governments during the crisis. Dukelow and Considine (Reference Dukelow and Considine2014: 58) associate the initial decision to impose austerity in Ireland with the historically weak position of the left's power resources. Hardiman and MacCarthaigh (Reference Hardiman and MacCarthaigh2013: 3) claim that ‘governments have some discretion over how and where they make’ changes to reduce budget deficits when experiencing bailouts, albeit within a heavily constrained fiscal environment. For Armingeon and Baccaro (Reference Armingeon and Baccaro2012), on the other hand, the arrival of the Troika substantially eroded national autonomy, reducing the ability of domestic actors to implement an autonomous policy platform. In reviewing social policy reforms across the bailout nations, they conclude that ‘Governments of different political orientations and of different parliamentary strength found themselves implementing essentially the same structural adjustment programme’ (2012: 267).

Moreover, while the period of the bailout was arguably one of policy ‘intrusion’ by the Troika (de la Porte and Heins, Reference De la Porte and Heins2015: 13), how, exactly, did intrusion operate? The IMF's insistence on conditionality as part of its loan agreements is well documented and Ireland's experience offers a potential example of policy ‘coercion’ (Obinger et al., Reference Obinger, Schmitt and Starke2013). However, the presence of the Troika arguably presented the Irish government with tremendous scope for ‘blame avoidance’ in imposing austerity (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994). Since the Asian financial crisis, the IMF has sought to move away from detailed policy conditionality towards outcomes-based conditionality, where specified deficit reduction targets are agreed and national governments are given ‘greater flexibility in choosing how to achieve the agreed results, reducing the degree of detail with which the Fund monitors programme implementation’ (IMF, 2002: 3; see also Khan and Sharma, Reference Khan and Sharma2003). This implies some degree of freedom to manoeuvre in terms of specific cuts made, and warrants further examination.

Even when the Irish government did implement the reforms that were advocated by the Troika, one cannot rule out the possibility that this arose from ‘persuasion’, even if we expect that the dominant motif was one of ‘powering’. As Weyland (Reference Weyland2005) argues, international organisations may not only influence national reforms through ‘foreign pressures’; nations may implement reforms due to a ‘quest for legitimacy’, out of perceived self-interest (‘rational learning’), or by following cognitive heuristics (rules of thumb) (Weyland, Reference Weyland2005).

The purpose of this paper is to examine the role played by the Troika in the politics of social security during Ireland's bailout between December 2010 and November 2013. During this period, the Troika visited Ireland on a quarterly basis. These missions typically lasted for 10 days, and included meetings with the Irish government and senior civil servants, unions, employers, civil society organisations and others. While these missions were the subject of much speculation in the national media, they were held in private. Following each visit, a quarterly monitoring report reviewing Ireland's progress was prepared separately by the IMF and the European Commission.Footnote 2 Each report included an appendix containing the updated Memorandum, detailing the policy conditionality associated with the disbursement of funds.

This paper makes an important contribution to the literature on the Eurozone crisis as it is one of the few studies (see also Pisani-Ferry et al., Reference Pisani-Ferry, Sapir and Wolff2013) that relies on in-depth interviews with participants involved in meetings with the Troika. These interviews provide first-hand accounts of the nature of interactions with the Troika, and provide a valuable supplement to analysis of material in the public domain. Previous research on the Eurozone crisis, in contrast, has largely focused on the nature of policies enacted in the bailout nations (see, for example, Hermann, 2014), or on the content of these quarterly review documents and/or MoUs (see, for example, Featherstone, Reference Featherstone2015).

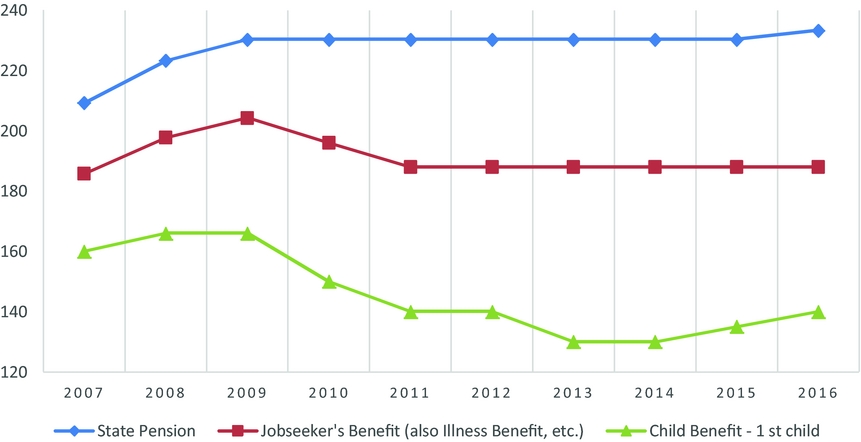

This paper does not document economic developments in Ireland in the lead-up to the crisis (see, for example, Donovan and Murphy, Reference Donovan and Murphy2013). However, before examining the influence of the Troika, in terms of social security reforms in Ireland during the period of the bailout, it is necessary to provide an outline of the nature of social security change in Ireland during the crisis. Changes in the value of the State Pension, Jobseeker's Allowance and Child Benefit post-2007 are presented in Appendix 1. A table containing details on changes in the rules of selected schemes is outlined in Appendix 2.

The initial crisis response by the Fianna Fáil/Green Party government comprised cuts to working age payments and Child Benefit, with the State Pension frozen in nominal terms. This government was replaced by a Fine Gael/Labour Party government in March 2011, shortly after the bailout was signed, and this latter administration imposed a freeze on the State Pension and working-age payments, but implemented further cuts to Child Benefit (see Appendix 1). Younger adults – initially those under 20, but incrementally extended by both governments to those aged 24 and under – have been segregated within the main working-age category and receive a payment of just over half of the main rate.Footnote 3 In addition to these changes to the value of some of the key payments, there have been numerous changes to scheme rules in order to reduce entitlements to social security, as well as the abolition of some smaller schemes (see Appendix 2).

In addition, there has been a greater emphasis on activating working-age claimants and a substantial re-organisation of employment supports, including the amalgamation of employment and welfare services into a new one-stop-shop, Intreo, and a new private, payment-by-results welfare-to-work scheme, JobPath, which will seek to activate the long-term unemployed and other claimants identified as being at risk of long-term unemployment. On the tax side, a series of new taxes and levies were introduced to broaden the tax base and increase revenue. The purpose of this brief outline is to ‘set the scene’, to provide context to the discussion that follows.

The paper comprises four sections. In the next section, the methodology of the study is outlined. The second section discusses some of the main themes that emerged from the interviews: crisis management in Ireland before the Troika arrived; the nature of Troika governance; and the extent of policy manoeuvre during the bailout. The conclusion summaries the key findings.

Method

The fieldwork conducted as part of this study comprised in-depth interviews with eight individuals who were involved in meetings with the Troika. Five respondents were working at civil society organisations (CSOs), and met with the Troika during (some of) their quarterly missions to Ireland. Three respondents were staff at the Department of Social Protection, who also met with Troika officials during these visits. The initial sampling frame intended politicians from the main political parties to be represented; however, these requests for interviews were rejected. Given the widespread speculation and political discussion about the nature and content of interactions with the Troika, a key criterion for inclusion in the sample was that respondents had themselves been involved in these meetings. The interviews were conducted in Dublin between March and August 2015.

The CSOs in questionFootnote 4 were invited to meetings with the Troika at government buildings; some also received field visits from the Troika members to inspect their work. The CSOs were invited to make representations at these meetings and their proposals were scrutinised by Troika officials. The interviews with CSOs discussed the number and nature of meetings with the Troika, the representations made to the Troika by the CSOs, and how these representations were received by the Troika and by the Irish government.

Departmental officials were asked about the nature of advice coming from the Troika, whether this was unanimous or varied by institution, how receptive the Troika were to government responses (especially when of a critical or ambivalent nature); the distinctive approaches taken by the two governments, and so forth. While these themes were guided by the extant literature, the open-ended nature of the interviews allowed for the exploration of issues that the respondents considered of importance. This is of particular significance given the relatively ‘closed’ nature of these interactions and, indeed, key findings presented below emerge from these ‘bottom up’ themes rather than questions that were asked by the interviewer.

The interviews were, in all cases bar one, conducted face-to-face and were recorded and transcribed verbatim (again, in all cases bar one). The transcripts were subsequently analysed by examining a number of pre-defined themes that emerged from the existing literature (see above), and a number of additional themes that emerged from the interviews themselves. In addition, I conducted a documentary analysis of the Troika's quarterly monitoring reports (Hick, Reference Hick2017). I have drawn on this material here at points where the documentary evidence helps to corroborate or call into question claims made during the interviews that were conducted.

Enter the Troika

Crisis management in Ireland & the ‘need’ for reform

To distinguish between the impact of Troika governance and Ireland's response to the crisis more generally, it is worth beginning by considering the measures that were proposed or implemented prior to the Troika's arrival. By the time Ireland signed its Memorandum of Understanding with the Troika in November 2010, two years had passed since the government was forced to issue a bank guarantee to prevent the collapse of one or more domestic banks. The intervening period had witnessed a collapse in property prices, the announcement of substantial losses in Ireland's banking system, the emergence of apparently fraudulent practices at some institutions, and the wider economy had slid into a recession.

This led to a belief or acceptance that there was a ‘need for reform’ and both Ministry officials and civil society staff described some of the subsequent cuts that have been implemented as being inevitable.

‘The increase in Universal Social Charge. The [income and health levies] which pre-dated the Universal Social Charge. Increases in income taxes. They started under the previous regime. They were continued under the current regime. They were inevitable because of the abject short-fall in revenue’ (CSO Interview 2).

-

Q: And where did that push for cuts to social security come from?

-

A: ‘The push was inevitable – they had to be’ [introduced] (Ministry Interview 1).

This official claimed that it was the ‘explosion of unemployment’ when the crisis hit that changed the policy direction in Ireland (Ministry Interview 1). This dramatically increased the functional pressure on Ireland's social security system, and exposed inadequacies which had been overlooked during the boom years. Speaking in relation to the activation reforms that were advocated by the Troika, one respondent noted:

‘Some of it I think was both the political and official system reacted to the crisis and previous criticisms, particularly of our social welfare system being too passive, which would have come from the OECD ad nauseam for many a long time . . . years of OECD and others saying, “the system is too passive, the system is too passive”. I think a number of senior officials went: “yes, the system is too passive” (CSO Interview 1).

Indeed, some respondents suggested that reforms enacted in response to the crisis should have been implemented many years previously. Reflecting on some of the revenue-raising measures which were introduced post-bailout such as a property tax and water charges, one official noted ‘I would argue we should always have had these things. Most countries have some sort of water charges’ (Ministry Interview 1).

The domestic origin of the cuts

It is perhaps not surprising, therefore, that the Irish government had started to implement fiscal consolidation and had imposed cuts and reforms to social security prior to the Troika's arrival at the end of 2010. The government officials I interviewed (Ministry interviews 1 & 2) stressed the domestic origins of the social security changes that were introduced, pointing to the timing of the cuts which were made. One outlined a summary of social security change during the crisis, before concluding: ‘I would include all of them, up to and including the pre-[Budget] 2011 as being effectively pre-Troika. . .and that's the vast bulk of the changes’ (Ministry interview 2). An examination of the timing of social security cuts can indeed be used to show that many were implemented before the Memorandum was signed. For example, the rate cuts for working-age adults and for Child Benefit, the substantial cut in Jobseeker's Allowance for younger jobseekers (initially for claimants under 20 years) were all implemented a full year before the Troika arrived in Ireland (Appendix 1 & 2).

In terms of providing a framework for fiscal consolidation, a key document was The Special Group on Public Service Numbers and Expenditure Programmes, led by Colm McCarthy. Published in July 2009, it recommended expenditure reductions of €5.3 billion, most of which was intended to be deliverable in 2010, including €1.8 billion of cuts from the budget of the Department of Social and Family Affairs (now Department of Social Protection). These included proposals for an across-the-board social security rate reduction of 5 per cent (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, McLoughlin, O'Connell, Slattery and Walsh2009: 187), as well as specific cuts, such as reductions in the value of Child Benefit (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, McLoughlin, O'Connell, Slattery and Walsh2009: 188), and an extension of the reduced rates of JobSeeker's Allowance for young people between 20 and 24 (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, McLoughlin, O'Connell, Slattery and Walsh2009: 190). These latter proposals were implemented in subsequent budgets, both pre- and post-Troika, and support claims that significant cuts were domestically chosen.

Similarly, the National Recovery Plan, published in November 2010 just before the bailout was signed, proposed a €15 billion four-year budgetary adjustment, of which one-third would come from tax rises and two-thirds from spending reductions (Government of Ireland, 2010: 9). This Plan subsequently formed the basis for the Memorandum with the Troika (European Commission, 2013: 30) and one community and voluntary sector respondent was certainly of the view that:

‘Quite a bit of what was in the Memorandum of Understanding . . . very much came from a number of Irish government officials . . . in terms of how they saw the cloth needing to be cut and how the system needed to change’ (CSO Interview 1).

Even for those reforms implemented after the Troika arrived, officials were keen to identify the origins of these reforms in policy documents published before the crisis. For example, a shift towards greater activation of the unemployed has been a dominant theme of policy in recent years, and was one of the primary themes of the Troika's quarterly monitoring reports. One official emphasised that the shift towards greater activation was proposed in Towards 2016, the final social partnership agreement agreed in Ireland (see Government of Ireland, 2006: 51).

What changed during the crisis was the impetus to translate these policy aspirations into concrete policy reforms. This meant that the Irish government was largely ‘on the same page’ as the Troika by the time the Memorandum was signed. As one CSO respondent noted:

‘I know at a European level, there are different views. Let's say in Greece, where the government and the Troika aren't on the same page in terms of the reforms that are going to be implemented, whereas here there was a sense that there was no great conflict’ (CSO Interview 3).

The nature of Troika governance in Ireland

Differences between the Troika institutions

While the Troika is comprised of three quite different institutions, it was the reputation of the IMF that was most discussed amongst commentators at the start of the bailout. This view was shared by the participants interviewed here:

‘When they came in first we were like [gasps] IMF and nobody when the ECB and the European Commission are here, but [gasps] the IMF is here, you know?’ (CSO Interview 3).

Despite this, and while differences between the IMF and the European institutions formed a consistent theme throughout the interviews, the specific position adopted by the institutions surprised many respondents. Most commented that they found the IMF more open to ‘social’ concerns than they had anticipated, and the European side less so. In an interview with two government officials, one noted that ‘the IMF had more of a social awareness’ than the European institutions, to which another official commented, ‘they had more of a social and political awareness’ (Ministry Interview 1), advocating the need for a social impact assessment of policy changes, and also more mindful of the political and thus practical difficulties involved in implementing of the Memorandum of Understanding. One community and voluntary sector respondent noted that:

‘In some ways the IMF, because it probably had a bloody nose in terms of previous experiences of structural adjustment in Latin America and other countries, em, had learned the hard way that you can't . . . that the social can't be the handmaiden of the economic entirely. Now, I think they're better at messaging that than necessarily practicing it, but they certainly, towards the latter half of their time here, were saying “we are as interested in the social sustainability of your society as we are about the macro-economy. That said, we have lent you money and we want the money paid back”’ (CSO Interview 2).

In contrast, the European institutions were perceived to be less open to such concerns:

‘. . .there's times I would have felt that the IMF were not quite in the space I expected, but the Commission were in that space’ (CSO Interview 1).

Theodoropoulou (2014: 22) and Pisani-Ferry et al. (Reference Pisani-Ferry, Sapir and Wolff2013: 22) have noted that the conditionality imposed by the European Commission was more detailed and prescriptive than that of the IMF.Footnote 5 Moving beyond the number of conditions imposed, we can ask whether the different institutions championed qualitatively different reforms in the area of social security policy. In a documentary and content analysis of the quarterly review documents, Hick (Reference Hick2017) shows that the primary emphasis of the IMF in terms of social security policy was in terms of advocating the greater targeting of universal income supports, while the Commission's focus was, to a much greater extent, on introducing labour market activation reforms. This distinction was emphasised by respondents, too:

‘. . .to a certain extent the tougher line on conditionality came as much or more from the Commission than it did from the IMF’ (CSO Interview 1).

Understanding the role of the ECB is rather more difficult because they did not publish separate quarterly review reports, and respondents indicated they engaged less than the other institutions in the discussion of proposals regarding social reform (CSO interview 2). In general, then, there was a widespread view that the IMF representatives were more open to arguments about the social impact of cuts than respondents had expected, but that the European institutions, and the ECB in particular, were less sympathetic to these concerns (Ministry Interview 2).

A focus on the resource ‘envelope’ or specific cuts?

The official position of the IMF is that they agree only the ‘resource envelope’ within which national governments must operate, in terms of agreeing deficit reduction targets with national governments; specific proposals may be raised, but these are not (in the main) imposed as long as the fiscal consolidation targets are met. If the measures identified by the Irish government to reduce spending failed to achieve the agreed budget deficit targets, additional action would be required, ‘if necessary through fallback options in relation to public sector wages and primary social welfare rates’ (IMF, 2011: 16). It is only where progress on agreed fiscal consolidation begins to falter that more punitive measures are to be implemented. This relates directly to the question of how intrusion under the Troika manifested itself.

The relative absence of detailed conditionality was discussed by respondents, with one Department official noting that, ‘in terms of absolute commitments, there are very few [contained in the Memorandum]’ (Ministry Interview 1) at least in terms of social security. In meetings:

‘Some of the mantras were “well, look, we're less concerned about how the adjustments are made, we just want overall, from a macro picture, for the Irish government to make those adjustments. However, we do have a number of recommendations, for example. . . ”’(CSO Interview 2).

This led to something of a tension between an official stance which emphasised only the resource envelope within which governments could operate and, at the same time, a desire for more specific reforms. This respondent continued:

‘So, it kind of went from “we're agnostic to [specific] cuts, as long as you make the macro” through to “well, actually, if you're really pushing us, we do have an opinion and it's more, cut the expenditure, so you cut certainly income supports, em, and you rationalise”, and that kind of thing.’ (CSO Interview 2)

The Troika argued that softening the proposed spending cuts would lead to a slower recovery and ultimately a more prolonged period of austerity. Given the fiscal consolidation that was planned, some social security cuts were inevitable given that this area accounts for a substantial proportion of public spending. However, one official noted that the Troika would have been open to a changing contribution to be made by social security – they would not have minded if €600m of social security savings were to become €500m, or €650m, as long as the budget deficit targets were met (Ministry interview 1).

This meant that, as Ireland had largely outlined the savings it was going to make in the National Recovery Plan, rather than insisting on specific policies, there was:

‘A consistent just querying, “do you not think replacement rates are still too high?”, and so on . . . that was there all the time, throughout.’ (Ministry Interview 2).

The focus on implementation

Given that the Irish government and the Troika were largely ‘on the same page’ as regards the need for fiscal consolidation (and thus spending cuts), one question is therefore what was of significance in terms of Troika governance. The over-riding focus of Troika governance was in terms of implementation, and the extent to which the agreed programme was being enacted:

‘What might have changed a little bit [in absence of the Troika] was the urgency with which it was implemented. That they, the fact that they, Troika were coming back every quarter, looking for updates and meeting with us and others and so on would have kept them [the Irish government] to programme’ (CSO Interview 3).

Both the civil servants and the civil society organisations noted that, in the absence of very detailed policy conditionality, the disbursements of funds was based on a holistic judgement about whether proposed measures would deliver the savings necessary to achieve the agreed budget deficit targets.

‘In a sense implementation was the Government's side; the Commission and the Troika are there to say “Well, you're doing well enough in order for us to give you more money”’ (CSO Interview 3).

One official, too, noted that the focus of talks was on the extent to which Ireland had implemented the measures announced in order to reduce the budget deficit sufficiently:

‘When they come in you know they asked all these questions about structural reform . . .umm. . . and, by and large, subject to speed and quality of implementation they didn't have all that much to add’ (Ministry Interview 2).

It was felt that there was a clear role played by the Troika in terms of ensuring the implementation of the Memorandum. Thus, one respondent noted that: ‘a lot of the decisions and the direction things were going in were already there . . . and you had someone coming in from outside to supervise it’ (CSO interview 3).

Nonetheless there was recognition that, without the Troika, implementing some of the measures that were subsequently enacted would have proved to be extremely difficult (Ministry interview 1), as Dukelow (Reference Dukelow2015: 107) has previously argued. Thus, a crucially important aspect of Troika governance, especially in the case of Ireland where acceptance of a ‘need for reform’ existed, was the degree of supervision and the emphasis on implementation through the quarterly review process.

The extent of policy manoeuvre

Finally, we focus on three moments of interaction between the Irish government, CSOs and the Troika that help to shed light on the degree of policy manoeuvre available to the Irish government during the bailout period.

Election of a new government

In March 2011, just months after the Memorandum was signed, a Fine Gael/Labour Party government replaced the incumbent Fianna Fáil/Green Party administration. One question is whether this new government was able to influence domestic social security policy or whether, during a bailout, domestic politics cease to matter. Hardiman and MacCarthaigh (Reference Hardiman and MacCarthaigh2013: 31) note that fiscal consolidation, and the greater reliance on spending cuts rather than tax rises, did not fundamentally change with the election of a new government in February 2011. As the IMF's Seventh Review noted (IMF, 2012: 20), ‘political commitment to [fiscal] consolidation has been a welcome constant, as reflected in the affirmation by the new government of the medium-term fiscal targets in the EU-IMF supported program agreed in December 2010’.

In terms of social security policy, one important difference between the Fianna Fáil/Green Party administration and the Fine Gael/Labour government that succeeded it was that while the former made outright cuts to the rates of social security payments (with the exception of pensioners, for whom rates were frozen), the Fine Gael/Labour government pledged to maintain the ‘primary social welfare’ rates – understood as being the main weekly payments.Footnote 6 In order to maintain this pledge but meet expenditure reduction targets this necessitated a great number of amendments to social security scheme rules (reductions in periods of entitlement, reductions in the value of pro-rata social insurance entitlements, and so forth), as well as the abolition of a number of smaller schemes, a continuation and extension of the policy of paying reduced rates of social assistance for young jobseekers, and reductions in Child Benefit, which were not considered to be included in this definition of the ‘primary social welfare’ rates (see Appendix 1 and 2). In this way, the new government changed the specifics of social security policy, but not the resource envelope set out in the Memorandum.

Another example of the exercise of internal autonomy can be seen in the decision of the Fine Gael/Labour government to reverse the €1 per hour cut in the minimum wage that was implemented by the Fianna Fáil/Green Party coalition. This change is significant because the initial cut in the minimum wage was itemised in the Memorandum agreed with the Troika and thus comprised one of the conditions for accessing bailout funds. Nonetheless, the new government was able to reverse this cut by making an equivalent and agreed change elsewhere – a temporary reduction in employers’ social security contributions (see European Commission, 2011: 14).

Attempts to change the balance of deficit reduction between tax rises and spending cuts

Nowhere was this ambiguity as regards the government's room for manoeuvre more apparent than in relation to the balance between tax rises and spending cuts to achieve the deficit reduction targets. For one CSO respondent, this apparent flexibility as regards policy specifics formed part of a two-sided narrative, in which the government boasted of successes won over the Troika while at the same time emphasising the limits of their own power:

One is that we were successful in renegotiating certain elements of it like the minimum wage and certain other areas, whereas on the other side they were saying “we're trapped in this programme. . . and we have to do what we're supposed to do”’ (CSO Interview 3).

As noted, the National Recovery Plan proposed that one-third of the fiscal consolidation would come from tax rises and two-thirds from spending reductions. Each of the CSOs I spoke to were advocating for a greater contribution to be made by tax rises, arguing that the policies implemented under the Troika undermined Ireland's efforts towards meeting the Europe 2020 poverty targets (especially, CSO interviews 4 and 5). The Troika insisted, however, that such decisions were domestic and that representations should therefore be made to the Irish government. Discussion on this issue also shed light on the relative balance between internal autonomy and external control, and the ambiguous boundaries between the two:

‘What was very clear constantly was that they were always saying to us “It's the government who makes the decisions, you elected the government you have to influence them”, and yeah [you] actually go to your government minister and they'd say “Well we have to do this because the Troika told us they have to do this”’ (CSO Interview 4).

‘Who was lying? I don't know. But both were saying that it was the other side’. (CSO Interview 3).

The ambiguity about who held ultimate responsibility over deciding the balance between tax rises and spending cuts, served, in practice, to deflect demands for changes to the balance announced in the National Recovery Plan. This could be seen to be one instance where the presence of the Troika provided scope for ‘blame avoidance’ in pursuing unpopular reforms (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994; Armingeon, Reference Armingeon2012).

Defending social security against pushes for further change

Both government officials and CSO staff were able to identify areas where Troika recommendations were at least partially resisted by the Irish government. In this section, we focus on three policy areas: the tapering of social security payments, sanctions for jobseekers and greater targeting of social security.

One concern raised by the Troika was that the levels of social security payment rates were too generous and provided a disincentive to work, particularly for low-paid workers:

‘. . .but the Government defended the basic social . . . they were cutting obviously all over the place, but they defended the line that they weren't going to cut the basic social welfare rate’ (CSO Interview 3).

Relatedly, an official noted that, at one point, the members of the Troika became ‘quite obsessive’ about the idea of tapering unemployment compensation, noting that the value of jobseekers' payments did not reduce over time, as is the case in many European countries (see also IMF, 2012: 70). Government officials responded that while payments were not tapered over time, the rates were not generous by European standards, other than when compared with those in the UK. Evidence to this effect from the Economic and Social Research Institute (Callan et al., 2012) was drawn on to justify the decision not to implement a policy change. A report was commissioned on the possibility of tapering unemployment compensation but it was decided not to implement this policy, with an official noting that ‘any government was unlikely to’ implement such a change (Ministry interview 1).

A second example is the Troika's recommendation to monitor and increase the use of sanctions for jobseekers who are deemed to make insufficient efforts to look for work. Prior to the bailout, the Social Welfare Act 2010 legislated for a reduction in social welfare rates of 25 per cent (‘penalty rates’) for persons who refuse to take-up an offer of training that is recommended to them. In a number of their review documents, the Troika argued that sanctions should be applied more frequently. In response to a question about how this recommendation was received by the Irish government, an official noted:

‘There wasn't an appetite in Ireland, and I think that's both official, political and in the population, for simply cutting people off, so what was decided, and I think this was planned before they came in as well, was to introduce penalty rates. [. . .] So, they [the Troika] would be asking the scale of them. And they were told. And the scale of them hasn't changed all that much’ (Ministry Interview 2).

Certainly, the Commission bemoaned the limited number of sanctions applied in 2012, noting that the ‘deterrent effect [of penalty rates] may yet not be fully operational’ (European Commission, 2012: 31). A strengthened system of sanctions was introduced in 2013, with provision for disqualification of up to nine months for those who continued, after receiving the penalty rate, to fail to engage with activation measures.Footnote 7 These stronger sanctions were welcomed by the IMF, who noted nonetheless that ‘the number of penalties applied overall remained small and [they] encouraged more effective steps to maximize jobseekers engagement’ (IMF, 2013: 23).

Official figures provided in response to a question in the Dáil (the Irish lower house) reveal that the number of claimants receiving a sanction increased from 1,519 to 3,395 between 2012 and 2013 (the final year of the bailout) but had increased to 6,743 by 2015.Footnote 8 Thus, penalty rates have evidently increased and claims that the government resisted the Troika's advice in this area can be questioned. Here was an instance where policy moved in the direction that the Troika favoured, if not to the extent that they wanted, and has continued in this direction in the period since the bailout ended.

Third, we can look to the end of the bailout and, indeed, to the post-bailout period to consider the extent to which the Troika's primary recommendations in relation to social security were adopted or not. We have noted above that the activation of working-age claimants was a particular concern for the Commission. While the quarterly review process criticised the pace and, at times, the ambition of activation reform in Ireland, the Commission did eventually welcome the activation reforms that were made, noting in the Second Post-Programme Review that ‘The establishment of the JobPath initiative was slow to begin with but is now proceeding according to plan’ (European Commission, 2015: 44).

In contrast, the IMF's calls for a more targeted approach to social security payments were only very partially heeded. In their final review document, they lamented that ‘measures to better target costly universal supports and subsidies (such as the child benefit, medical cards, and subsidies on college fees) were not part of the budget [2014] package’ (IMF, 2013: 16). In the post-bailout period, the IMF has continued to argue that ‘better targeting [of social security] could help protect the most vulnerable in society at lower cost and produce superior social outcomes’ (IMF, 2016: 9). But, as Ireland was achieving its deficit reduction targets (‘making the macro’), it was not forced into making these less palatable choices, demonstrating again the significance of Troika governance in terms of its primary emphasis on deficit reduction targets.

In the initial post-programme period, the IMF argued that ‘nominal public sector wages and social benefits must be held flat for as long as feasible and the authorities will need to continue to seek savings across the budget’ (IMF, 2014: 14). Yet, in the two budgets which have been held since exiting the bailout (Budgets 2015 & 2016), Child Benefit has been increased by €10 per month, and the State Pensions by €3 per week (see Appendix 1). While these are modest changes, they nonetheless are at variance with the IMF's recommendations, and were described by one official as an instance where ‘national policy triumphed over Troika policy’ (Ministry Interview 1).

Lastly, the policies pledged in advance of the 2016 general election can help to shed light on the longer-term influence of the Troika, despite not yet being implemented. Perhaps most surprising of all is that, having resisted the tapering of social security payments (downwards) during the bailout, Fine Gael went into the 2016 election pledging to taper Jobseeker's Benefit by increasing short-term payments in nominal termsFootnote 9 – pledging to increase this to €215/week for the first 3 months of unemployment, before a phased reduction to the current level of €188/week after six months (Fine Gael, Reference Gael2016). Thus, the idea of tapering has seemingly been adopted by the Irish government, even if the reason for this (social security rate restraint) has been resisted to a greater degree.

Thus, there was some scope for policy manoeuvre within the constraints of a framework for deficit reduction. A new government made changes to social security policy on coming to office in 2011, and some attempts to fend off additional cuts were successful. For CSOs, the very ambiguity in terms of who decided the balance between tax increases and spending cuts served to choke off their attempts to lobby for a different balance. In practice, while the Irish government ignored some Troika proposals (e.g. around targeting or rate restraint), there were no movements away from the deficit reduction plan agreed with the Troika in late 2010.

Conclusion

The arrival of the Troika in the capitals of Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus has led many commentators to point towards the politics of ‘powering’ through which the Troika enforced their will by imposing ‘strict and binding conditions for the bailed-out countries’ (Petmesidou and Glatzer, Reference Petmesidou and Glatzer2015: 165). In this paper we have examined the politics of social security during Ireland's bailout, considering the extent to which the cuts that were imposed align with the period of the bailout, the extent of domestic room for manoeuvre during the bailout period, the significance of Troika governance, and evidence of ‘persuasion’ as well as ‘powering’ during this period (Weyland, Reference Weyland2005).

By the time the Troika arrived in Ireland in late 2010, a view had crystallised that major policy errors had been committed during the Celtic Tiger years, and that the budget deficit that emerged after the collapse of the property market required fiscal consolidation to be enacted. The yields demanded on sovereign bonds, when combined with the pressure from the European Central Bank on Ireland to accept a bailout, meant that there was little choice but to undertake fiscal consolidation, unless Ireland was to exit the Eurozone. A Keynesian-style stimulus could not have been financed, however desirable it might have been for the macro-economy. Such consolidation, which included severe cuts to social security, was well under way before the Troika arrived in Ireland, and the government's proposals for further consolidation, as outlined in the National Recovery Plan, formed the basis for the Memorandum of Understanding between the Irish government and the Troika.

While fiscal consolidation was inevitable, however, there remained space for non-trivial policy choices within what was an extremely restrictive fiscal climate. Ireland could have chosen a different balance between tax rises and spending cuts in order to achieve the deficit targets agreed with the Troika (by contrast, Iceland chose a 50:50 balance between tax rises and spending cuts during its bailout from the IMF). Some changes were made by the new government in 2011 in terms of cutting entitlements via the scheme rules rather than cutting primary weekly payments further (see also Hick, Reference Hick2014). The prioritisation of pensioners over children, a common theme in many nations during the crisis, was an inherently political choice. Thus, the losses could have been distributed in different ways, with those on lower incomes and/or children protected to a greater extent.

The distinctive, and sometimes surprising, positions adopted by the IMF and European Commission featured in many of the interviews I conducted, and emerged as a theme at the very outset of the fieldwork. These differences were both in terms of their sensitivity to social concerns, as well as their emphasis on different reforms. The Troika's focus on the deficit reduction targets and not (in the main) specific reforms meant that the normal politics of welfare was not over-ridden entirely, and there remained scope to discuss the specific policies that would contribute to deficit reduction. Moreover, the government was able to successfully resist proposals by the Troika (and especially the IMF) to retrench social security further, demonstrating that national autonomy was not entirely lost. Defending social security sometimes involved commissioning research in order to justify the absence of further change. It was also fundamentally dependent on the deficit reduction targets being met – there was a recognition that, had progress against deficit reduction targets began to falter, the government would have been forced to impose additional cuts to headline rates of social security, including to the State Pension (CSO interview 1).

Thus, ‘powering’ came in the form of enforcing deficit reduction rather than demanding specific changes to social security. Moreover, since the Irish government was largely ‘on the same page’ as the Troika in terms of the need for cuts, ‘coercion’ in terms of implementing such reforms was not necessary. But the choice not to implement deficit reduction or cut spending did not exist, at least as long as Ireland wished to remain in the Eurozone.

Moreover, there is evidence that the Troika's influence was not only constraining, or ‘powering’, but that it also encompassed ‘persuasion’. This is most notable in terms of the proposal to taper social security rates, which was resisted successfully during the bailout period but later became a manifesto commitment for the main governing party. In terms of sanctions, too, developments did not move as far or as fast as the Troika would have wished, but the number of sanctions has increased nonetheless, including during the post-bailout period.

Ireland's exit from its bailout does not mark an end to fiscal discipline as it is now subject to surveillance and enhanced fiscal governance under the European Semester, which significantly constrains domestic policy choice (Laffan, Reference Laffan2014). Moreover, the Eurozone remains a far-from-ideal currency union, and the ECB interest rate is likely to prove inappropriate for Ireland again at some point in the future. Since any loss of competitiveness relative to core countries cannot be dealt with through currency depreciation (or, external devaluation), resorting periodically to austerity (or, internal devaluation) seems likely. The crisis has required economists to re-think the significance and desirability of monetary union in Europe (see, for example, Pisani-Ferry, Reference Pisani-Ferry2013). For academic Social Policy, too, there is a challenge to understand to a greater extent the economic and thus public spending implications of monetary union; the new, strengthened fiscal rules within the Eurozone; and the risks to people's living standards posed by both private and public debt. While the Troika have now exited the stage, the politics of fiscal discipline has not.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges funding from the British Academy (Award SG141878). Thanks are also due to participants at the 2015 Social Policy Association conference in Belfast and the 2015 ESPAnet conference in Odense, for their comments and suggestions and, most importantly, to the respondents who took the time to speak with me about this important period. Any errors of fact or interpretation are mine alone.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Nominal value of three social security payments, 2007–2016 Note: Amounts are in € per week for State Pension and Jobseeker's Benefit), per month for Child Benefit.

Appendix 2. Selected changes in scheme rules post-crisis