In June 1540 Henry viii’s commissioners removed Lincoln’s treasures to the Tower of London. Besides the cathedral’s four main shrines, these included six chalices (one pure gold, five silver-gilt), twenty-one reliquaries of various forms and materials (including silver-gilt, crystal and ivory), twenty-four chests (including one of ivory containing relics), fourteen crosses (one of pure gold, the others of gold and silver), five candelabra (including the two huge gold candlesticks given to the cathedral by John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster), four gospel books (with covers of silver-gilt and precious stones), eight mitres (encrusted with gold thread, pearls, sapphires, diamonds and rubies) and 168 sets of chasubles and copes, including a purple set designed for annual use by Lincoln’s boy bishop. In all ‘there was taken out of the cathedral at that time, in gold, two thousand six hundred twenty-one ounces. In silver four thousand two hundred eighty-five ounces besides a great number of pearls and precious stones, which were of great value, as diamonds, sapphires, rubies, turkey carbuncles etc.’.Footnote 1 When these were removed from the cathedral, the treasurer flung away his keys of office, saying ‘now that the whole treasure of the church has been seized, the office of treasurer has come to an end’.Footnote 2

Lincoln, of course, was not an isolated case. Between 1536 and the death of Edward vi in 1553, all the monastic and secular foundations in England saw their treasure removed by the Crown Commissioners. With them went the need for a treasure house to conserve them. As a result, the treasure houses of English cathedrals have been largely forgotten, though Fergusson has reminded us how fruitful it can be to make a close examination of the documentary history and architectural features of one such building at Canterbury,Footnote 3 and recent studies by European historians have reawakened interest in treasure houses in France and Germany.Footnote 4

Sources testify to the determination of medieval Christians to recognise the spiritual value of church treasure over and above its worldly worth. In the Vie de Saint Ursmer de Lobbes, the word ‘treasure’ is used for the body of the saint, and in the Life of St Trond this ‘treasure’ is described as ‘precious’.Footnote 5 In his Miracula sancti Germani, Heiric d’Auxerre speaks of the body of S Germain as ‘a treasure to be adored’, and in the Translatio Sancti Valeriani (Tournus, 1120–40) the ‘treasure’ belonging to the monks of Noirmoutier is stated to be the body of S Philibert, as well as the precious objects associated with his cult.Footnote 6

Nevertheless, many other sources make it equally clear that the worldly value of these objects was of concern to medieval clerics. The accumulation of treasure certainly provided a safeguard against hard times. For example, in the twelfth century the cathedral of Ely placed the treasures of the church, including a large chalice and a silver tower-pyx, at pawn with London merchants, while obtaining loans from the Bishop of Lincoln against the surety of vestments, including the chasuble given to the monastery by King Edgar. In addition, the abbey’s great cross and a gospel book (both also donated by King Edgar) were placed with the Jews in Cambridge against a surety of 200 marks.Footnote 7 In Prague, a silver head of a statue of John the Baptist was pawned in 1374 and a silver head reliquary of St Stephen was pawned in 1380.Footnote 8 At Lincoln, a chapter act of 1392 records the pawning of an image of John the Baptist that was made of gold and silver and kept in the treasury.Footnote 9

LINCOLN CATHEDRAL TREASURE HOUSE

Medieval documents refer to a treasure house at Lincoln both directly and indirectly. The Consuetudines (the chapter’s record of its customs) of 1267 refer to the catalogue of books belonging to the chapter as being kept in thessauria [sic] – ‘in the treasury’.Footnote 10 An unpublished chapter act of 1306–7 records that a chest in the treasury was repaired at a cost of twelve shillings. Part of this expenditure was for a smith, suggesting deficiencies with the chest’s structure or lock.Footnote 11 The cathedral statutes forbade anyone except the chapter clerk to remove any records from the treasury, unless he executed a bond to return them within a short time. For instance, the dean was forced to go through such a procedure in order to take the charters of the church of Ashbourne to London for confirmation in 1311.Footnote 12 This indicates that the treasure house also served for storing legal documents, such as deeds and charters, as well as precious liturgical objects. A chapter act of 1309 records the decision to use a chalice of no great value ‘for the morrow mass’ because it took place before the treasury was unlocked, and the chalice would therefore have to be stored overnight in an altar cupboard.Footnote 13 Another unpublished act of 1392 records that an image of John the Baptist, made of gold and silver, was kept in the treasury.Footnote 14

Other documents record the existence of a revestiarium (‘vestry’) at Lincoln. The Consuetudines of 1267 direct that the bishop, when about to perform his office, should be led by the dean and one other dignitary from the revestiarium either to the high altar or to his throne (deducentes eum de revestiario ad altare vel ad sedem cathedralem).Footnote 15 This vestry is recorded as having an altar upon which were two large tabernacles, with figures of ivory, and a representation of the Passion; it was also the place where the silver-gilt socket for the processional cross was kept.Footnote 16 The fact that it was thus used to deposit some of the cathedral’s sacred treasure reinforces the theory that it was a chamber situated within the treasure house.

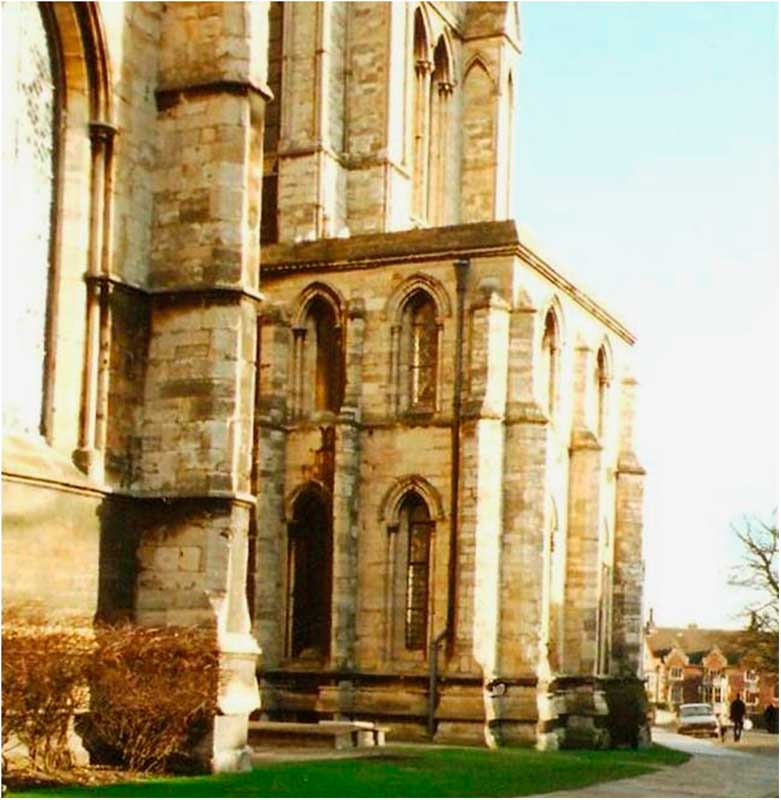

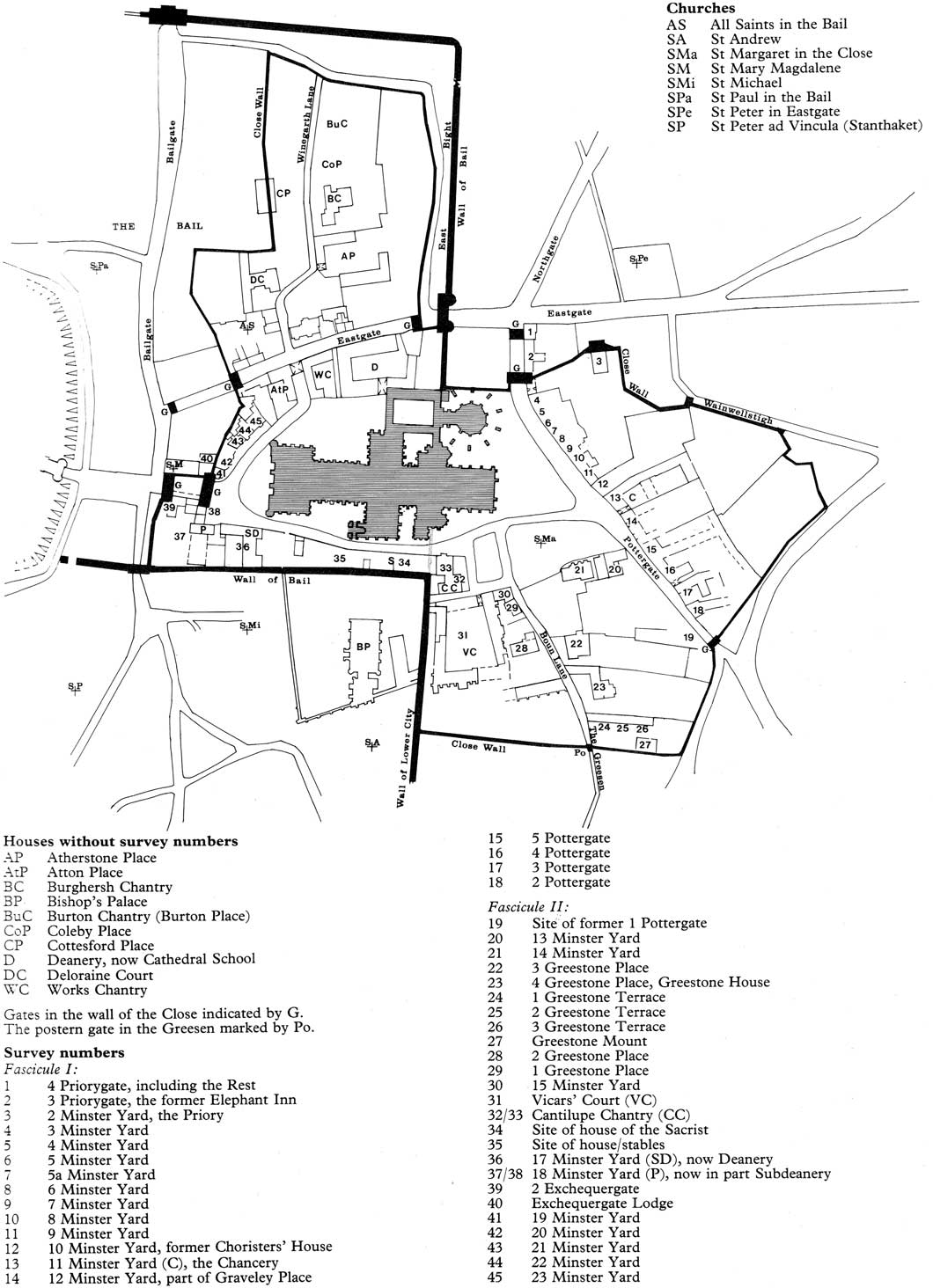

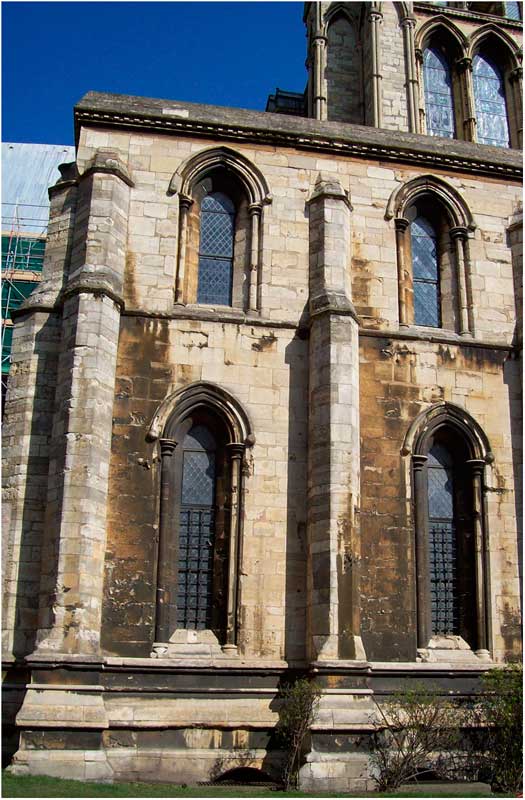

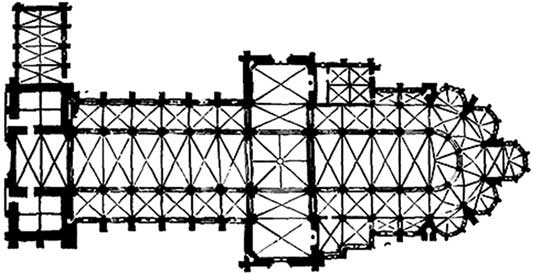

While these documents indicate the existence of a treasure house, they give no evidence of its location. However, in the archives of Lincoln Cathedral, manuscript A/2/23, fol 3v, dated 10 March 1324, refers to ‘a house belonging to the cathedral fabric, situated to the south of the cathedral’s treasury’ (domum fabrice ecclesie nostre ex australi parte thesaurarie ecclesie). The fortunate existence of this document allows for the precise identification of the location of the house, which in turn allows us to identify the thirteenth-century annex to the south-east transept of Lincoln Cathedral (figs 1 and 2) as the cathedral’s thesaurarium. The house to which the manuscript refers was assigned to the sacrist in the late thirteenth century.Footnote 17 The holder of this office was the deputy to the treasurer and it was therefore fitting that he should enjoy such proximity to the treasure house. At other cathedrals – for instance, Salisbury – the sacrist’s house was actually attached to the treasure house itself.Footnote 18

Fig 1 Lincoln Cathedral treasure house, viewed from the south west. Photograph: © author

Fig 2 Plan of Lincoln Cathedral and its Close, with the location of the sacrist’s house (34) ‘lying to the south of the cathedral’s treasury’. Source: Jones et al Reference Jones, Major and Varley1987, 74–5

Moreover, a later document records that this same house had a well in the garden, from which, in 1428, it was said that the water was carried by ‘divers channels’ for cleaning the church.Footnote 19 The treasurer was responsible for keeping the sacred treasures of the church clean, the duty of which he deputised to his subordinate, the sacrist, who was also responsible for washing and cleaning the cathedral’s vestments. The existence of the well within the sacrist’s garden and its proximity to the treasury cannot be accidental. Before 1288, according to a cathedral charter of that date, this house was occupied not by the sacrist but by the goldsmith of the shrine of St Hugh.Footnote 20 Therefore, the person responsible for an outstanding amount of gold lived within close range of a building expressly designed to protect such riches.

Unusually, the money left by pilgrims at the shrine of St Hugh was not used for the fabric.Footnote 21 Instead, the sum of 1,000 marks (£666 13s 4d) was raised every year for Lincoln Cathedral by a fraternity established in the early thirteenth century by Robert of Coggeshall, abbot of a small Cistercian monastery in Essex. Under the bishopric of William of Blois (1203–6), a special chantry – the ‘Works Chantry’ – was established to guarantee daily masses for the souls of benefactors to the Fabric Fund of the cathedral.Footnote 22 Indulgences (the remission of temporal punishments brought about by sin) also contributed to the Fabric Fund: before 1200, St Hugh himself instituted an indulgence of eighty days of enjoined penance for all who contributed towards the building of the cathedral;Footnote 23 an indulgence of forty days for the same cause was granted by Bishop William of Blois who, moreover, offered thirty-three masses weekly for everyone who gave alms to the building.Footnote 24 Indulgences continued through the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries: in 1266 the Bishop of Lichfield granted fifteen days to those ‘who shall contribute of Fabric (of Lincoln)’, while forty days were granted by the Bishop of London in 1303, an offer repeated in 1304 by the Bishop of Glasgow, in 1305 by the Bishop of Carlisle, in 1308 by the Bishop of Worcester and in 1314 by the Archbishop of Canterbury.Footnote 25 As a result of all these indulgences, funds flowed in, creating a pressing need for a secure place to deposit, count and distribute the money.

Some documents indicate the post-Reformation use of the treasure house. The first-floor chamber has been in continual use as the canons’ vestry since the Dissolution to the present day, suggesting that it continued a role already established before the Dissolution. In 1609 the Dean and Chapter took proceedings against a priest-vicar for using as a dovehouse ‘the place over the vestry where divers chests of evidences and writings of the church, the lord bishop, the dean and others do remain and by the doing of the said pigeons, the said chests, writings and evidences are spoiled and much hurt’.Footnote 26 The said ‘place over the vestry’ is the chamber on the first floor of the building, which has been used as the cathedral’s song school since 1801.

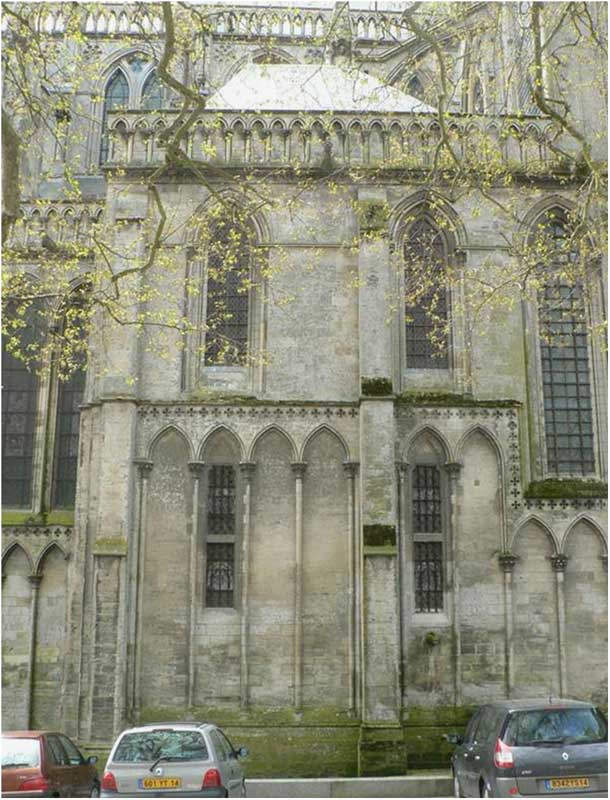

THE EXTERIOR

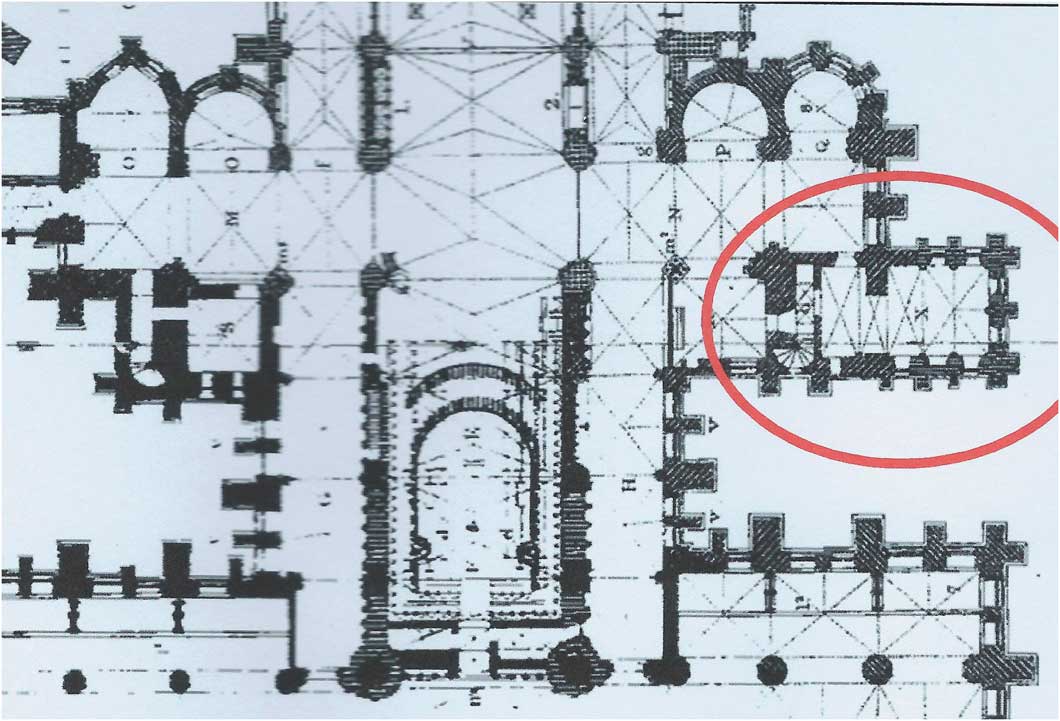

Lincoln Cathedral was a secular rather than a monastic foundation. Unlike the establishments of regular monks, the church and houses of secular canons were not, until the late thirteenth century, encompassed by a protective close wall.Footnote 27 Therefore, the treasure house would be more visible to the laity than was the case in a monastery. It was built onto the south-western angle of the south-eastern transept, and comprised three storeys, the lowest of which is a crypt (figs 3 and 4). The building measures 50ft (15.24m) in length (north–south) by 25ft (7.62m) in width (east–west), and thus stands on a double square. Its designers were able to take advantage of the idiosyncrasies of the plan of the south-east transept, for although each transept appears to have a western aisle, in fact this comprises only one bay, followed by a massive staircase.Footnote 28 The staircase blocks do not stretch to the end of the transept, however, but terminate 25ft (7.62m) short. This has resulted in an angle between the staircase blocks and the transept ends into which the semi-independent treasure house was installed. That the building is an addition to the transept can be seen, both on the exterior and the interior, from the way in which it is wrapped around the transept’s south-western buttresses.

Fig 3 Plan of Lincoln Cathedral choir and east transepts, showing the location of the treasure house. Source: The Builder 1892, 61, no. 2544

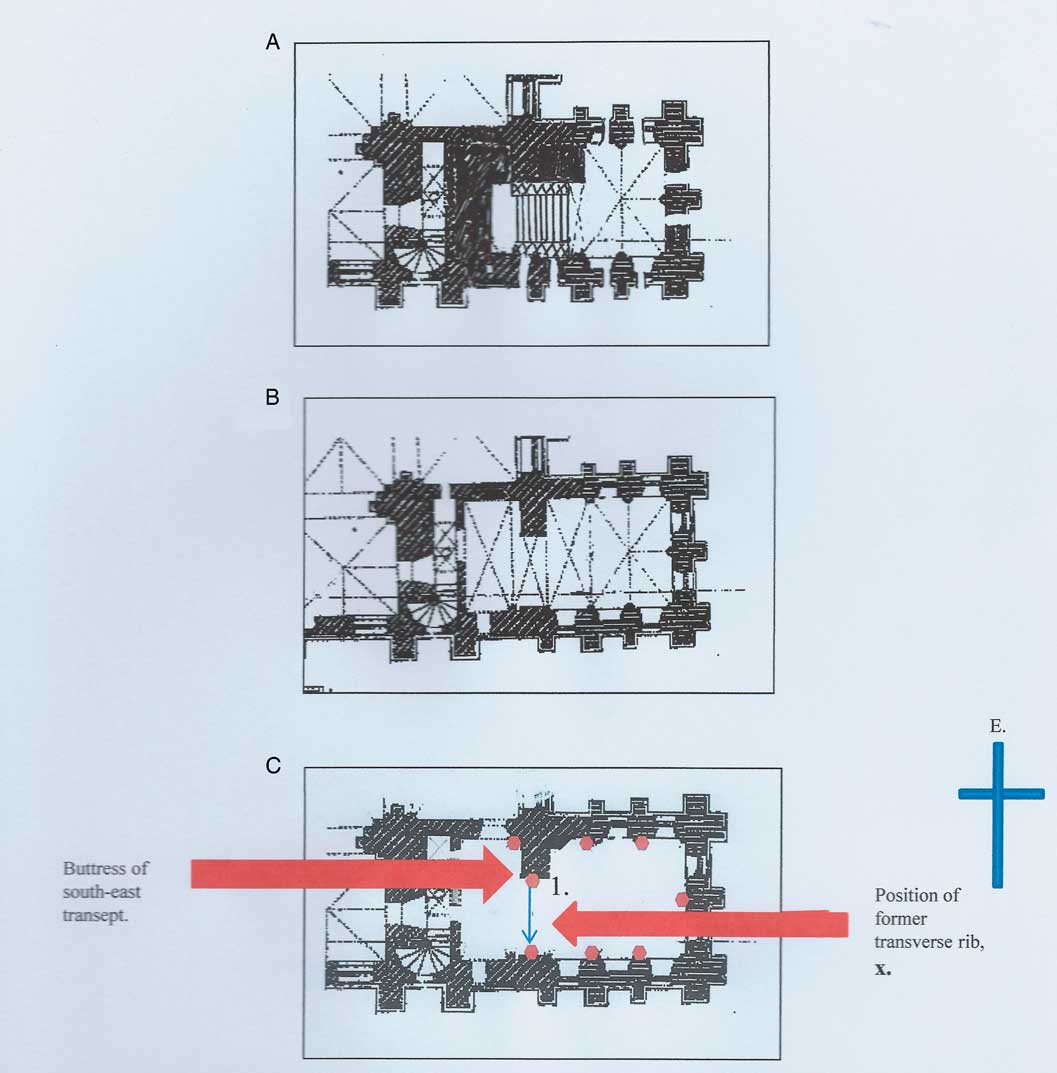

Fig 4 Lincoln Cathedral treasure house: (A) plan of the crypt; (B) the lower chamber; and (C) the upper chamber, showing the position of the corbel heads that formerly carried the vaulting ribs. Drawing: The Builder 1892, 61, no. 2544, adapted by the author

The exterior of the building reflects its role and function as a treasure house not through exuberance but by asserting its autonomy – it is set on an elaborately chamfered and moulded three-stage plinth, which does not conform in height or design with that of the transept – and through its proportions, which make no attempt to conform to those of the building to which it is attached.

The crypt is lit by windows whose tops pierce the plinth (fig 5). These windows are round-headed, unlike any of the other windows in the Gothic parts of the cathedral – that is, the parts belonging to the campaign that began with St Hugh’s choir in 1192 and continued through the thirteenth century. This choice of style might not be unexpected for an early thirteenth-century building, but, as will be shown, the treasure house dates from after the mid-thirteenth century, by which time such windows would have looked out of keeping and old-fashioned. Their style is even more noticeable within the crypt. In 1976 François Bucher drew attention to the retardataire nature of thirteenth-century metalwork reliquaries and liturgical artefacts. This insight was reinforced by Aachim Timmerman in 2015, who contended that ‘in the sphere of ars sacra … these architectural miniatures are often retrospective in character, copying, for instance, essential design features of late antique or early Christian buildings’. Bucher suggested that the style was chosen because it ‘gave the viewer the impression of greater antiquity, which reinforced the authenticity of the relic’.Footnote 29 This deliberate choice of an old-fashioned style is found in many treasure houses, both in Britain and in Europe and becomes even more noticeable in the later Middle Ages.Footnote 30 Perhaps Bucher’s suggestion is as valid for the depositories of treasure as for their contents. The use of seemingly old-fashioned features could have conveyed messages of continuity and stability in order to reassure medieval viewers about the validity of the buildings’ sacred treasures.

Fig 5 Lincoln Cathedral treasure house from the south, showing the round-headed windows of the crypt just peeping up above the ground. Photograph: © author

Chamfered buttresses divide the building into two bays on the south side and three narrower bays on the west side. On the opposite east side, the building is only two bays wide because it abuts the great angle buttress of the south-east transept. Above the plinth, the exterior elevation is divided into two by a string course. Each storey has lancet windows with keeled shafts in each bay, those on the first floor being taller than those on the second. The windows have continuous keeled roll mouldings and the capitals are moulded, with no stiff-leaf ornamentation. The parapet, decorated with billet moulding, was created in 1854. Writing in 1883, Venables recorded that battlements with merlons had originally crowned the building.Footnote 31 If such battlements were original, the treasure house would have given a message of unassailability that was consistent with its role of store house.

THE INTERIOR

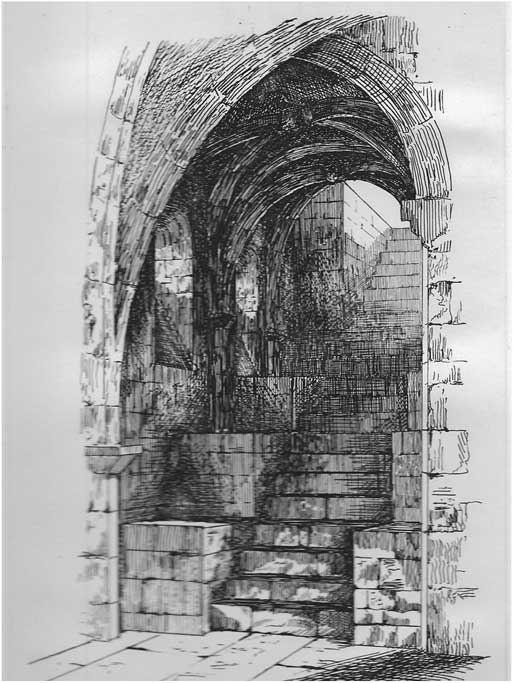

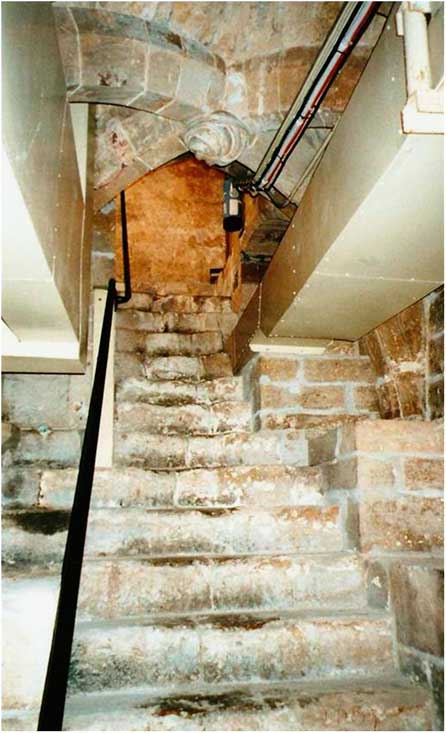

Within the interior of the cathedral, the treasure house is invisible (fig 6). Its former door (now walled up) was plain and straight-headed. The crypt is reached by a straight staircase of twenty-two steps (figs 7 and 8), now accessible only from the exterior of the treasure house via the door in the west wall created during the nineteenth century. However, in 1870 the crypt was said to be ‘approached through a trap-door in the pavement near the vestry’.Footnote 32 So far it has not been possible to find the original opening.

Fig 6 The south and west walls of the south-eastern transept of Lincoln Cathedral, behind which lies the treasure house. Photograph: © author

Fig 7 The crypt of Lincoln Cathedral treasure house: the view from the south. Source: Gibney Reference Gibney1870

Fig 8 The crypt of Lincoln Cathedral treasure house, the view from the south. Photograph: © author

Measuring 25 by 20ft (7.62m by 6.10m), the crypt is lit by deeply splayed, round-headed windows situated in the same bays as the fenestration of the first and second floors. At least one of the windows has bars, which appear to be original. The staircase and the crypt are rib-vaulted, with single-chamfer ribs. Figure 8 indicates the considerable difficulty of studying the crypt. Its floor has been raised and its internal spaces subdivided to accommodate the cathedral’s central-heating boiler. Its staircase is covered by quadripartite vaults, as is the northernmost bay of its main space. The crypt’s most impressive vault consists of an octopartite rib vault, of which one rib has been omitted to create a distinctive seven-part vault (fig 9). This has three distinctive bosses, the decoration of which comprises: (a) heavy, concentric rolls; (b) a series of fanning-out segments, rather like Victorian jelly-moulds; or (c) both these elements. These bosses will be returned to below as they are useful in dating the building.

Fig 9 The seven-ribbed vault over the main space of the crypt of the Lincoln Cathedral treasure house, slightly obscured by modern pipework. Photograph: © author

The difficulty of access, its barred windows and its thick walls ensure that the crypt is well suited to the function of treasury, a location matching the reference to ‘some secret place in the Minster’ where an Elizabeth Darcy in 1412 directed that her legacy of £200 (to be distributed to chaplains annually for masses) be kept.Footnote 33 With its seven-rib vaulting and elaborate bosses, this was a room of distinction and status, fit for storing treasures of the highest value, both in material and in spiritual terms.

The lower chamber of the treasure house (now divided by an east–west wall), was originally undivided and measured 50 by 25ft (15.24m by 7.62m) feet (see fig 4). It is easy to see that it has been built onto the south-east transept because the angle buttress of that earlier building intrudes into the room. In the north-east corner can be seen a corbel carved with stiff-leaf. This is the only example of this type of decoration within the treasure house, and it is possible that the capital is a reused element from St Hugh’s choir.

The room’s vaulting is splendid. Its ribs, unlike those of the crypt vault, are moulded and provided with impressive foliated bosses. First, from the north, are three bays of quadripartite vaults. The final (southern) bay of the chamber, is almost square and is covered by a seven-rib vault (like the chamber below it) (fig 10). This is the same choice of vault made for the vestiarium at Canterbury (fig 11). There, as here, is ‘a single, dramatic, high-rising, fully-vaulted space … composed of octopartite ribs’.Footnote 34 This vaulting serves to endow the southern bay with its own autonomy and authority. The chamber at Lincoln may not be centrally planned, as was the vestiarium at Canterbury, nor octagonal, as with the treasure houses at Salisbury Cathedral and the cathedral of Saint-Omer; nevertheless, the vaulting of Lincoln’s southern bay serves to create a space that recalls such interiors.

Fig 10 The vault over the main space in the lower chamber of the Lincoln Cathedral treasure house. Photograph: © author

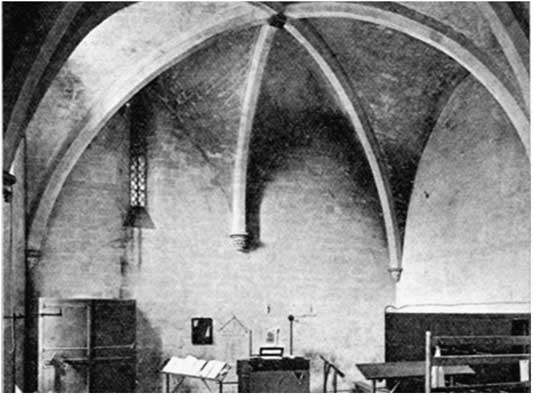

Fig 11 The octopartite rib vault in the vestiarium of Canterbury Cathedral. Photograph: © author

The lower chamber of the treasure house at Lincoln is lit by large lancet windows which have a continuous keeled roll-moulding. These, together with the richness of the moulded ribs and foliate bosses, contribute to the splendour of the room (fig 12). There is now no sign of an altar. In 1898 it was recorded that several recesses had been covered over with wainscot and plaster. These would have provided secure space for storing treasures. In fact, a walled-up cupboard can still be seen on the south wall of the vestry, its dimensions and characteristics being close to the cupboards with which the vestiarium at Canterbury was provided.

Fig 12 Lincoln Cathedral treasure house, lower chamber: the view to the south. Photograph: © author

What was this room originally? Was it the room referred to in cathedral documents that is the chapel on which sumptuous reliquaries were placed on the altar, and within which was stored the huge silver-gilt socket of the processional cross and the great baculus (‘staff’) ornamented with silver? Is this the place where, according to the Novum Registrum of c 1440, the sacrist must unlock the doors at ‘the first chime of matins in the morning, and again when the bell sounded for evensong’, and where those canons not well enough to go into the choir were permitted to say their offices?Footnote 35 Its splendour suggests that this was the case. On the other hand, it may well be that the chapel of St Peter – which was situated just beyond this lower chamber, in the transept on the other side of its wall – functioned as the sacristy and that this newer space was in fact a vestiarium created to provide much-needed extra space for the canons to store their vestments and enrobe for Mass. This is all the more likely because there is no sign that it contained a piscina or lavatorium for cleansing Eucharistic vessels, whereas there is one situated next to the altar of the chapel of St Peter.

However, the room does contain a fireplace at the north end of its west wall. This, invisible for many years, was revealed in a site-visit to Lincoln in the summer of 2011. Although still largely concealed, it is possible to discern its projecting hood and pronounced roll-moulding, characteristics which conform to thirteenth-century fireplace design (fig 13). Amongst many other examples, it finds a close match with the one in the bedroom of St Thomas’s Tower, a building created in the Tower of London for Edward i in the later thirteenth century. At Lincoln, it has already been shown that the treasurer had overall responsibility for the washing of the cathedral’s treasures, deputised to his subordinate, the sacrist. Two hitherto unnoticed references in the 1260 Lincoln Consuetudines make the role of the fireplace clear. In listing the duties of a treasurer, it is specified that he is responsible for providing firewood and, significantly, it is directed that, in preparation for the Maundy Thursday foot-washing ceremonies, the servants of the church must heat up water on the stove in the treasury.Footnote 36

Fig 13 The remains of a fireplace on the west wall of the lower chamber within Lincoln Cathedral treasure house. Photograph: © author

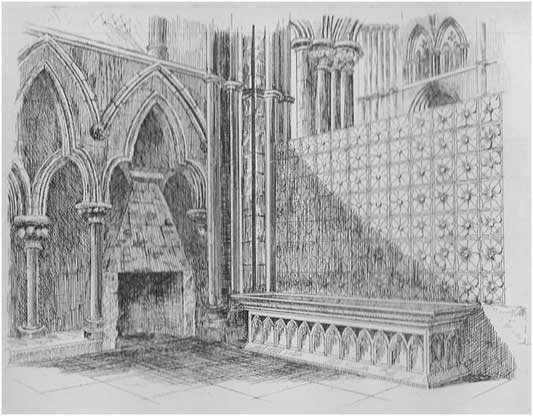

Clearly the position of the fireplace proved unsatisfactory. In the fourteenth century a new space devoted to liturgical ablution was created in the western aisle of the adjacent transept connected by a new doorway punched through the wall between it and the treasure house.Footnote 37 The room was provided with a splendidly decorated stone lavatorium and a fireplace with which to warm water (fig 14). The number of masses increased during the course of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, in line with the increase in the number of chantries, until forty masses a day were being said between 5am and 11am at the altars in the cathedral by the early sixteenth century.Footnote 38 This would explain why additional space for washing Eucharistic vessels was needed. It could also be that this room, provided as it was with a stone bench on its western and southern sides, was used on certain occasions for liturgical foot-washing. At Canterbury Cathedral it was within the vestry that a new archbishop’s feet were ceremonially washed.Footnote 39

Fig 14 Lincoln Cathedral: the west chapel of the south-eastern transept, showing the fireplace and lavatorium. Source: Gibney Reference Gibney1870

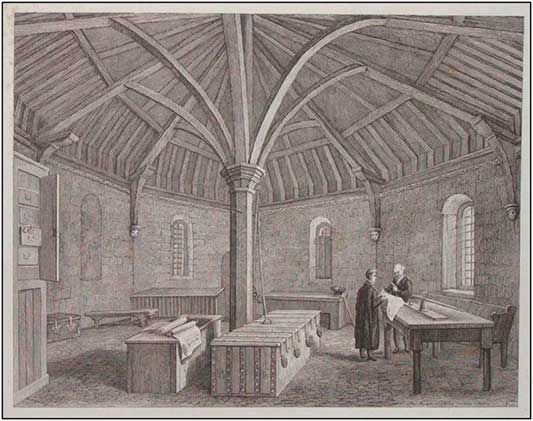

Access to the upper chamber of Lincoln Cathedral’s treasure house – the one in which the seventeenth-century priest-vicar kept pigeons, now a song school – is gained by the staircase originally built as part of the south-east transept. It is entered by a round-headed, unmoulded doorway and it mirrors the dimensions of the chamber below it (figs 4 and 15). The room is well lit by seven large lancets (one now blocked) with continuous keeled roll mouldings, two in each of the east and south walls and three in the west, again echoing the fenestration of the floor below.

Fig 15 Lincoln Cathedral treasure house: the upper chamber, looking east. Source: © Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, B68/2158

The post-Reformation wooden floor is higher than the original one and the room now has a flat ceiling. The position of eight fine large corbels, carved in the form of human heads, suggests that it originally had a stone vault that mirrored those of the crypt and the lower chamber. Seven of these are situated between the room’s windows, at a height of approximately 4ft (1.22m) above the present floor, which would have been about 5ft (1.52m) above the original floor (see fig 4). The seventh head occupies the northern end of the eastern wall, and it is set much higher, at a height of approximately 8ft (2.44m) from the floor. At present the corbels perform no structural function. However, a report by Essex claimed that the treasury building had become ruinous through ‘the insufficiency of the abutments to support the thrust of the vaulting’.Footnote 40 This in itself suggests that the upper chamber did indeed have stone vaults, which could have been taken down and replaced by a flat ceiling in 1854 when a new parapet replaced the battlements that originally crowned the building.Footnote 41 In fact, there is incontrovertible evidence that ribs covered the room, since the damage created by one of them is still visible. When the transverse rib x (shown on fig 4) was created, the stiff-leaf foliage of the capital of the pre-existing buttress to St Hugh’s choir had to be cut away to accommodate it, and the signs of this are still visible. The cornice above the capital was also damaged, but can be seen to have been replaced, probably at the same time that the 1854 work to the exterior parapet was being carried out. The position of the corbels is consistent with the pattern of vaulting of the chamber below, three quadripartite vaults and a seven-rib vault. The buttress of the south-east transept is responsible for the higher position of one corbel (see fig 4, A). The buttress obtrudes into the room. Therefore, the rib linking it to the vault’s keystone would reach this buttress at a higher level (this arrangement also happens in the chamber below). So these sculptures are indeed in situ and they were created specifically for the room.

There are no records of the original function of this upper chamber at Lincoln. It is possible that relics were stored here. Upper chambers of treasure houses elsewhere are recorded as performing such a role. For instance, it was within the upper chamber of the treasure house of Amiens c 1220 that the cathedral’s most prized relics, the head of St John and the bones of St Firmin, were located.Footnote 42 At Bayeux Cathedral a splendid cupboard for relics still exists within the upper chamber of the treasure house. The treasure house of the cathedral of Saint-Omer, Pas-de-Calais, was the depository for the head of St Omer.Footnote 43 It is likely that the upper room of the treasure house of Lichfield Cathedral was the depository of St Chad’s head. In addition to its major shrines, Lincoln Cathedral is known, from its inventories, to have possessed relics.Footnote 44 The cathedral statutes ruled that in processions the bearers of the cathedral’s relics should walk in between incense bearers and the subdean.Footnote 45 Lincoln Cathedral’s feast of its relics was held on 14 July.Footnote 46

However, there is an argument that at least some of the cathedral’s relics were stored, not in this chamber, but behind the high altar. A substantial stone screen divided the presbytery from the Angel Choir. It was approximately 49ft (14.94m) wide and 10ft (3.05m) deep. A door in the west side of the screen gave access to a passageway, or chamber within it, which ran north–south. A newel staircase in the north of this chamber gave access to an upper level. The screen was described by Bishop Sanderson in 1641: ‘in the east part stood an altar. A door into the room there at each end. Upon the room stood the tabernacle. Below many closets in the wall’.Footnote 47 A useful comparison can be made here with a similar screen carrying relics situated behind the high altar of Winchester Cathedral. Its dimensions were approximately 28ft (8.53m) wide (north–south) by 12ft (3.66m) deep (east–west). In the mid-thirteenth century a ‘long recess, fronted by a metal grill’ was inserted on the west side of the platform.Footnote 48 Worcester Cathedral also had a similar feretory platform built before 1224 and destroyed in 1822.Footnote 49

If the ‘closets in the wall’,Footnote 50 in the screen behind the high altar at Lincoln, held the cathedral’s relic collection, what then was the function of the upper chamber within the treasure house? A useful comparison can be made with the upper chamber of the treasure house at Salisbury Cathedral (fig 16). An 1834 view shows the great chests with which the room was filled, one of which remains chained to the wall to this day. As shown earlier, the upper chamber at Lincoln contained ‘chests of evidences and writings of the church’ after the Reformation, and it would not be unreasonable to believe that it had done so before. At Exeter Cathedral a late thirteenth-century chamber is documented as a scaccarium (‘exchequer’).Footnote 51 In the thirteenth century, ecclesiastical exchequers, created to account for the Church’s fabric money, came into being.Footnote 52 They emulated the Royal Exchequer. The twelfth-century Dialogus de Scaccario described the room where the formal process of drawing up accounts of money received and money spent took place.Footnote 53 Such a room necessarily had to be hidden, but also needed to be large enough for the table on which money was counted and recorded by clerks. Adequate light was needed for the work, necessitating a number of windows. The scaccarium at Exeter Cathedral is the upper chamber within the late thirteenth-century north annex of the choir (fig 17). Like the upper chamber in Lincoln, it is well lit. It retains its original rib vault supported by corbels carved with heads that bear a resemblance to the ones at Lincoln (figs 18 and 19). Although the function of the upper chamber of Lincoln Cathedral’s treasure house cannot be established with any certainty, the similarities between it and the example at Exeter suggest that it, too, may have been a scaccarium.

Fig 16 The upper chamber of Salisbury Cathedral treasure house. Source: Fisher Reference Fisher1834

Fig 17 The scaccarium (‘exchequer’) of Exeter Cathedral. Photograph: © author

Fig 18 An example of a corbel head which formerly supported rib vaulting in the chamber of Lincoln Cathedral treasure house. Source: © Conway Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, B68/2162

Fig 19 Exeter Cathedral: an example of a corbel supporting the vault ribs in the upper chamber of the northern treasure house. Photograph: © Exeter University

DATING

Now that the treasure house of Lincoln Cathedral has been examined, its date must be established. The type of decoration on the bosses of the vault of the crypt at Lincoln appears elsewhere in the cathedral (for example, on the arcades that decorate the screen separating the choir from the aisles in St Hugh’s choir). These date from after the collapse of the central tower of the cathedral at the end of the 1230s. The profiles of the ribs of the ground-floor chamber echo those of the vaulting of the south-east transept, which dates, according to dendrochronological evidence, to after 1247.Footnote 54 The rich decorative foliate bosses of the ground-floor chamber seem even later. They recall those of the high vault of the Angel Choir (after 1255). They are also close in style to those of the high vault of the transepts of Westminster Abbey, which cannot date before the 1250s. Such similarity with Westminster is not confined to boss decoration. The corbel heads in the upper chamber of the treasure house at Lincoln bear a resemblance to work in the south transept of the abbey (St Faith’s Chapel) that must also be after 1250. Could these features have been added to a building that was already complete, by a team of masons who were working on the Angel Choir? That would mean that they were carved in situ, which seems unlikely. It therefore seems reasonable to date Lincoln Cathedral’s treasure house to the 1250s.

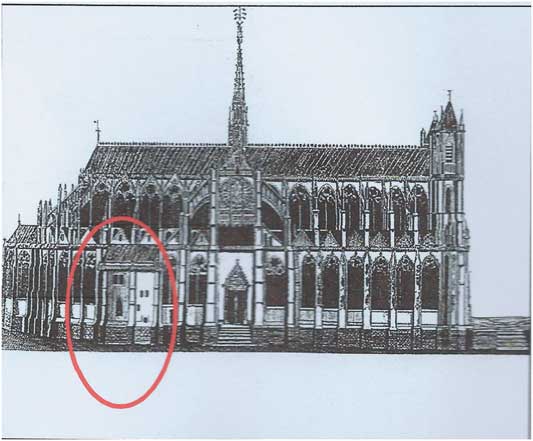

It now remains to examine the extent to which the treasure house at Lincoln conforms in style to the treasure houses favoured by secular canons elsewhere. In the first half of the thirteenth century, the cathedral of Amiens had a three-storey annex attached to the north side of its choir (fig 20), as did the cathedral of Beauvais (fig 21).Footnote 55 Later in the century a similar structure was provided for the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris. At Bayeux, also, there is a thirteenth-century treasure house of the same form (figs 22 and 23). In England, a rectangular two-storey treasure house was created at Chichester in the mid-thirteenth century (fig 24).Footnote 56

Fig 20 Amiens Cathedral, showing the treasure house originally attached to the north of the choir. Source: Murray Reference Murray1996, pl 78

Fig 21 The treasure house at Beauvais Cathedral. Source: Murray Reference Murray1989, pl 33

Fig 22 Bayeux Cathedral: the treasure house from the south. Source: Morelle Reference Morelle2007, fig 35

Fig 23 Plan of Bayeux Cathedral. Source: Vallery-Radot Reference Vallery-Radot1958

Fig 24 Chichester Cathedral, the treasure house: view to the west. Source: Corlette Reference Corlette1901, 87

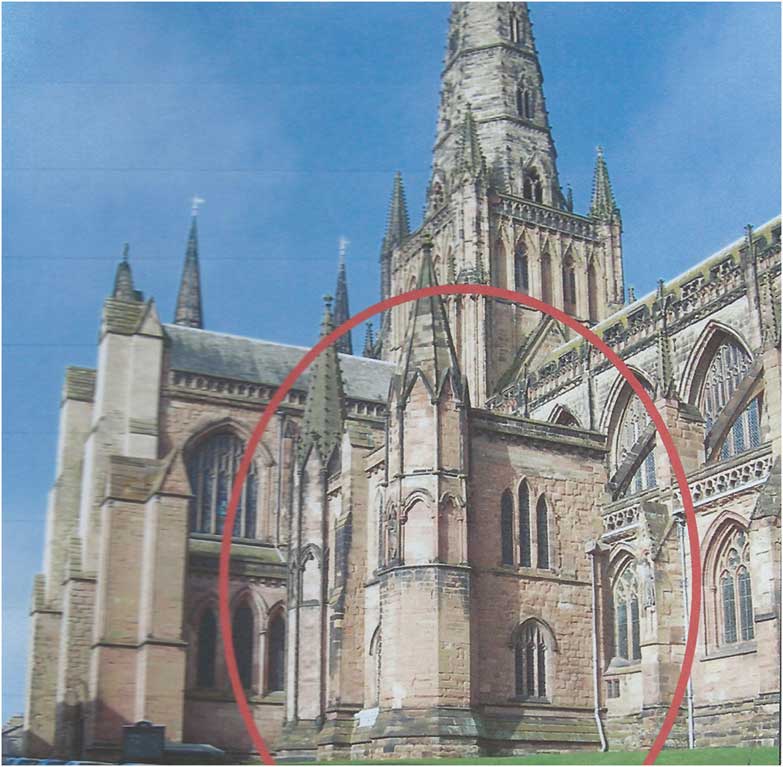

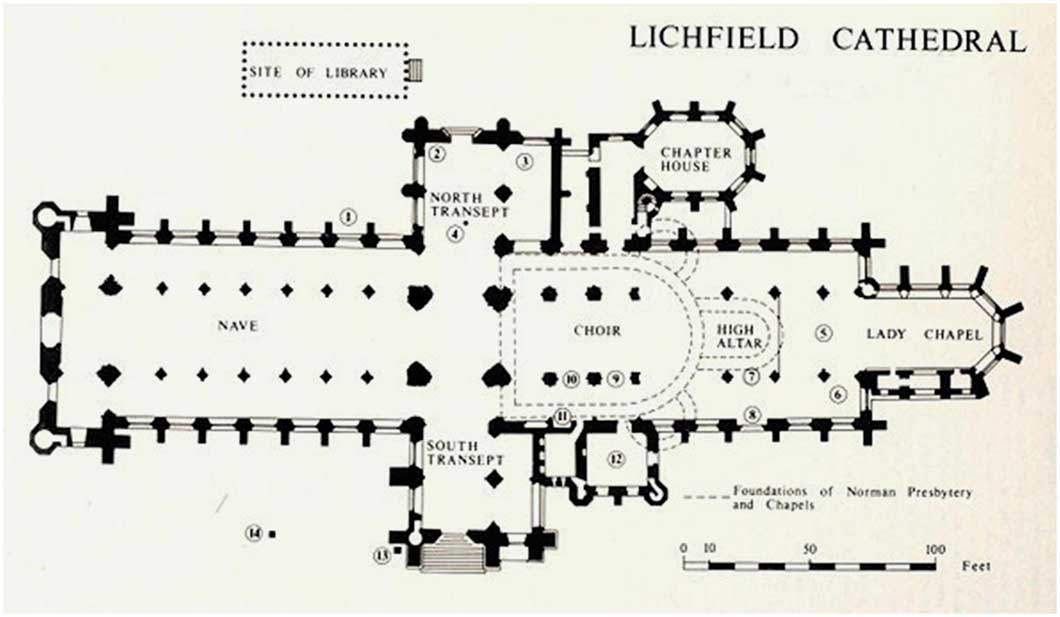

A close match to Lincoln Cathedral treasure house is a three-storey annex attached to the choir of Lichfield Cathedral, of which a detailed archaeological survey was undertaken by Warwick Rodwell in 1985–6 (figs 25 and 26).Footnote 57 Like Lincoln, it consists of three floors, including a vaulted crypt, and, again like Lincoln, it extends 25ft (7.62m) from the cathedral. Here again only two floors are clearly visible from outside the building. Similarly, to Lincoln, viewed from the exterior the building asserts its autonomy and status through its proportions and through the fineness of its architectural details, especially those applied to the turrets and to the fenestration. Within the building are the cupboards that are needed for a treasure house and, within the south-west turret, a well providing the water needed to wash the Eucharistic vessels and to allow their contents to return directly to the earth. This building can be dated to the mid-thirteenth century. Its turrets recall those of Lincoln Cathedral’s south-east transept, dated to c 1247.Footnote 58 A sacrist’s roll of 1345 records that the relic of the head of St Chad was kept in its upper chamber.Footnote 59 It seems likely that the upper chamber of the treasure house at Lichfield was intended from the start to house the head of St Chad, rather than function as a chamber devoted to the creation and conservation of documentary material. In this instance the upper chamber above the chapter house was evidently used for that purpose.Footnote 60 If the upper room of the treasure house at Lichfield was indeed the shrine for the head of St Chad, this might explain the embellishment on the exterior. In particular, the turrets, with their elaborate arcading, give the building the appearance of a scaled-up reliquary.

Fig 25 Lichfield Cathedral, the treasure house: view from the south east. Photograph: © author

Fig 26 Lichfield Cathedral: plan, showing the treasure house. Source: The Builder 1891, 60, no. 2505

CONCLUSION

Claire Labrecque has pointed out that ‘despite the fact that numerous French cathedrals possess, or have possessed, a treasure room worthy of interest, architectural historians and other historians have until now totally ignored this type of building’.Footnote 61 Her statement is no less valid in terms of treasure houses in Britain. This article has sought to redress that balance by bringing the treasure house of Lincoln Cathedral to the attention of scholars, a task which is all the more rewarding since its function during the Middle Ages is validated by reliable documentary evidence. Such a study is vital at a time when treasure chambers are being put to reuse. For instance, the upper chamber of the northern treasure house at Exeter Cathedral has recently lost its role as the choir practice room. A visit to the treasure house at Salisbury Cathedral reveals the kind of damage to the fabric that such rooms have recently suffered. English sacristies, vestries and treasure rooms were indispensable during the Middle Ages. The hope of this paper is to allow their return to the status that they were accorded by medieval Christians.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DEDICATION

Many people have assisted in the preparation of this paper. I owe particular thanks for advice and encouragement to the Journal’s anonymous reviewers and to Dr Michael Carter, FSA, Dr Laura Cleaver, Professor Paul Crossley, FSA, Professor Philip Dixon, FSA, Professor John Milner and Dr Mike Rogers.This paper is dedicated to the memory of Miss Kathleen Major, FSA, FBA.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- AMSO

-

Archives municipales de Saint-Omer

- Cal Pat Rolls

-

Calendar Patent Rolls of Henry III, 1232--47 (HMSO, London)

- LCA

-

Archives of the Dean and Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral

- RA

-

Registrum Antiquissimum of the Cathedral Church of Lincoln: see Foster 1973