Introduction

A prominent bimodal conceptualisation of aggression classifies it as either: (i) spontaneous (referred to as reactive or impulsive aggression), or (ii) planned (referred to as proactive, premediated or instrumental aggression) (Babcock et al., Reference Babcock, Tharp, Sharp, Heppner and Stanford2014; Wrangham, Reference Wrangham2018). Impulsive aggression has generally been found to be more characteristic of clinical samples and premeditated aggression more characteristic of delinquent or criminal populations (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Youngstrom, Steiner, Findling, Meyer, Malone, Carlson, Coccaro, Aman, Blair, Dougherty, Ferris, Flynn, Green, Hoagwood, Hutchinson, Laughren, Leve, Novins and Vitiello2007). The essential feature of intermittent explosive disorder (IED) as defined in both DSM-IV and DSM-5 is the occurrence of repeated episodes of impulsive aggression resulting in verbal or physical assaults or property destruction.

The first population studies on the epidemiology of DSM-IV IED in the USA were undertaken using the World Mental Health (WMH) surveys version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Coccaro, Fava, Jaeger, Jin and Walters2006; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Green, Hwang, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2012). In the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), IED prevalence among adults (18 years or older) based on a ‘broad’ definition of IED requiring three or more impulsive anger attacks in the lifetime was estimated to be 7.3%, decreasing to 5.4% based on a ‘narrow’ definition requiring three or more anger attacks in the same year (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Coccaro, Fava, Jaeger, Jin and Walters2006). In response to reviewer feedback, the WMH-CIDI diagnostic algorithm was subsequently modified to further require that anger attacks should cause at least some degree of interference with respondents' work, social life or relationships, thus bringing the diagnosis of IED into line with the other WMH-CIDI DSM-IV diagnoses. We refer to this revised algorithm as the ‘conservative’ definition of IED, and we applied it in our first cross-national report on IED which found lifetime prevalence ranging across countries from 0.1% to 2.7% with a weighted average of 0.8% (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Lim, Hwang, Adamowski, Al-Hamzawi, Bromet, Bunting, Ferrand, Florescu, Gureje, Hinkov, Karam, Lee, Posada-Villa, Stein, Tachimori H, Xavier and Kessler2016, Reference Scott, De Jonge, Stein and Kessler2018). The sociodemographic correlates of lifetime risk of IED were being male, young, unemployed, divorced or separated and having less education. The median age of onset of IED was 17 and prior traumatic experiences involving physical (non-combat) or sexual violence were associated with increased risk of IED onset (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Lim, Hwang, Adamowski, Al-Hamzawi, Bromet, Bunting, Ferrand, Florescu, Gureje, Hinkov, Karam, Lee, Posada-Villa, Stein, Tachimori H, Xavier and Kessler2016, Reference Scott, De Jonge, Stein and Kessler2018).

That earlier cross-national study focused on IED as a single diagnostic entity; the present study focuses on IED subtypes. It is a notable feature of IED as defined in DSM-IV and DSM-5 that the aggressive outbursts potentially classifiable as IED span a wide spectrum from non-destructive (verbal only) through destruction of property to hurting people. This gives rise to the possibility that IED could be characterised by distinct behavioural subtypes, and although few studies have investigated this, one study did find that comorbidity patterning varied by DSM-5 IED subtypes (verbal aggression only, physical aggression only, or both) (Look et al., Reference Look, McCloskey and Coccaro2015). In the WMH surveys, we have a sufficiently large number of respondents diagnosed with IED to be able to classify IED subtypes according to the type of aggressive behaviour. In this study, we use the same conservative definition of IED applied in our earlier cross-national report, and we have created five mutually exclusive behavioural subtypes. Our research questions were: (i) whether these behavioural subtypes would be predominantly associated with different types of comorbid mental disorder; and (ii) whether they would vary in associated suicidal behaviour and functional impairment.

Methods

Samples and procedures

This study uses data from all WMH surveys that measured IED (online Supplementary Table S1). A stratified multi-stage clustered area probability sampling strategy was used to select adult respondents (18 years+) in most WMH countries. In most countries, internal subsampling was used to reduce respondent burden and average interview time by dividing the interview into two parts. All respondents completed Part 1, which included the core diagnostic assessment of mood disorders, most anxiety disorders, substance use disorders and IED, and also assessed suicidality and sociodemographics. All Part 1 respondents who met lifetime criteria for any mental disorder and a probability sample of respondents without mental disorders were administered Part 2, which assessed post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, childhood impulse-control disorders, psychotic symptoms, physical health, functional impairment, psychological distress, childhood adversities and service use. Part 2 respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection for Part 2 of the interview to adjust for differential sampling. Additional weights were used to adjust for differential probabilities of selection within households, to adjust for non-response and to match the samples to population sociodemographic distributions. All respondents provided written informed consent and measures taken to ensure data accuracy, cross-national consistency and protection of respondents are described in detail elsewhere (Kessler and Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004, Reference Kessler and Ustun2008).

Measures

Intermittent explosive disorder

All surveys used the WMH survey version of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 3.0) (Kessler and Ustun, Reference Kessler and Ustun2004), a fully structured, lay-administered, face-to-face interview, to assess lifetime history of DSM-IV mental disorders. DSM-IV Criterion A for IED requires ‘several discrete episodes of failure to resist aggressive impulses that result in serious assaultive acts or destruction of property’. This was operationalised in the CIDI by requiring the respondent to report at least three attacks in the same year of at least one of three types of anger attacks: (i) ‘when all of a sudden you lost control and broke or smashed something worth more than a few dollars’; (ii) ‘when all of a sudden you lost control and hit or tried to hurt someone’; and (iii) ‘when all of a sudden you lost control and threatened to hit or hurt someone’. A 12-month diagnosis was assigned if those meeting lifetime criteria reported at least three attacks in the past 12 months.

DSM-IV criterion B for IED requires that the aggressiveness is ‘grossly out of proportion to any precipitating psychosocial stressor’. This criterion was operationalised in the CIDI by requiring the respondent to report either that they ‘got a lot more angry than most people would have been in the same situation’ or that the attacks occurred ‘without good reason’ or ‘in situations where most people would not have had an anger attack’.

DSM-IV criterion C for IED requires that the ‘aggressive episodes are not better accounted for by another mental disorder and are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition’. This was assessed through a series of questions (see (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Coccaro, Fava, Jaeger, Jin and Walters2006) for details) that ruled out IED diagnosis if anger attacks occurred exclusively when respondents had been drinking or using drugs, when they were in a depressive or manic episode, or as a consequence of an organic cause such as epilepsy, head injury or use of medications.

In this paper, we have applied the conservative definition of IED, requiring that respondents reported that their anger attacks caused at least some degree of interference with their work, social life or relationships. This is the same diagnostic algorithm used in our recent cross-national reports (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Lim, Hwang, Adamowski, Al-Hamzawi, Bromet, Bunting, Ferrand, Florescu, Gureje, Hinkov, Karam, Lee, Posada-Villa, Stein, Tachimori H, Xavier and Kessler2016, Reference Scott, De Jonge, Stein and Kessler2018).

DSM-IV v. DSM-5 criteria

DSM-5 criteria recognise two different patterns of the aggressive outburst: high frequency/low intensity (criterion A1: non-destructive verbal or physical aggression occurring at least twice weekly for at least three months) or low frequency/high intensity (criterion A2: at least three destructive outbursts within a year-long period) (Coccaro et al., Reference Coccaro, Lee and McCloskey2014). The diagnostic algorithm used in the present study requires three aggressive outbursts within 1 year, but as noted in our earlier paper (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Lim, Hwang, Adamowski, Al-Hamzawi, Bromet, Bunting, Ferrand, Florescu, Gureje, Hinkov, Karam, Lee, Posada-Villa, Stein, Tachimori H, Xavier and Kessler2016) there was insufficient information on the lifetime frequency of specific types of aggressive outburst to confirm whether those meeting the DSM-IV criteria operationalised in this study would also meet DSM-5 criteria.

IED subtypes

IED subtypes were mutually exclusive categories based on the type of behaviour during anger attacks. The CIDI screening questions for IED are based on the assumption that hurting other people is inherently threatening. Therefore, all respondents are asked whether they have ever in their life ‘had attacks of anger when all of a sudden [they] lost control and broke or smashed something worth more than a few dollars’ and whether they have ever ‘had attacks of anger when all of a sudden [they] lost control and hit or tried to hurt someone’. However, only respondents who answer ‘no’ to this second question are asked whether they have ever ‘had attacks of anger when all of a sudden [they] lost control and threatened to hit or hurt someone’. Given this skip logic in the CIDI, the number of possible subtypes is 5. Subtype 1 consisted of people whose anger attacks destroyed property only; subtype 2 consisted of people whose anger attacks threatened people only; subtype 3 consisted of people whose anger attacks hurt people but not property (with or without threatening); subtype 4 destroyed property and threatened people; subtype 5 destroyed property and hurt people.

Impairment and suicidality

The assessment of impairment included questions about lifetime impairment as well as impairment in the past 12 months. The lifetime questions were asked about the financial value of all the things the respondent ever broke or damaged during an anger attack and the number of times either the respondent or someone else had to seek medical attention because of an injury caused by one of the respondent's anger attacks. The 12-month questions asked respondents to rate the extent to which their symptoms interfered with their lives and activities in the worst month of the past year using the Sheehan Disability Scales (Leon et al., Reference Leon, Olfson, Portera, Farber and Sheehan1997). These are 0–10 visual analogue scales that ask how much a focal disorder interfered with home management, work, social life and personal relationships using the response options none (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–10). All respondents were asked whether in their lifetime they had ever seriously thought about committing suicide, and, if so, whether they had ever made a plan or attempted suicide.

Statistical analysis

Cross-tabulation was used to determine the prevalence of IED and its subtypes. We used logistic regression to examine the association between IED (subtypes) and lifetime comorbidity, lifetime suicidality and 12-month impairment due to IED. Logistic regression was also used to examine the association between the severity of IED-related violence and these outcomes. All analyses controlled for the country of origin of the participant, as well as participant's sex, age and educational attainment. Because the data were clustered and weighted, standard errors were estimated using the Taylor series linearisation method (SUDAAN 11.0.1).

Results

Prevalence of IED and its subtypes

Table 1 shows that the overall lifetime prevalence of IED in all countries was 0.8%. The table also shows the prevalence of the five behavioural subtypes. The most common subtype, with a prevalence of 0.4%, was the subtype with the most severe consequences, involving anger attacks that both destroy property and hurt people. The next most common subtype (‘hurt people only’: 0.2%) involves acts of aggression that result in people (but not property) being hurt. The other three subtypes are characterised by acts of aggression that do not result in harm to persons and these were the lowest prevalence, at around 0.1% each.

Table 1. Lifetime prevalence of narrow IED (with impairment) and its subtypes

Overall prevalence does not equal the sum of the prevalence of subtypes due to rounding.

Narrow IED is defined as hierarchical IED, with the added criteria that the respondent must have had three or more attacks in a single year at least once and that the respondent reports that the anger attacks interfere with work, social life, or personal relationships to at least some degree.

IED subtypes are based on behaviour during anger attacks. Respondents were asked whether they ever destroyed property or hurt people during an anger attack. If they reported never having hurt someone, they were asked whether they had ever threatened to hurt someone.

a Nominator N (number of participants reporting the outcome).

b Denominator N (number of participants asked the question).

c Percentages are based on weighted data.

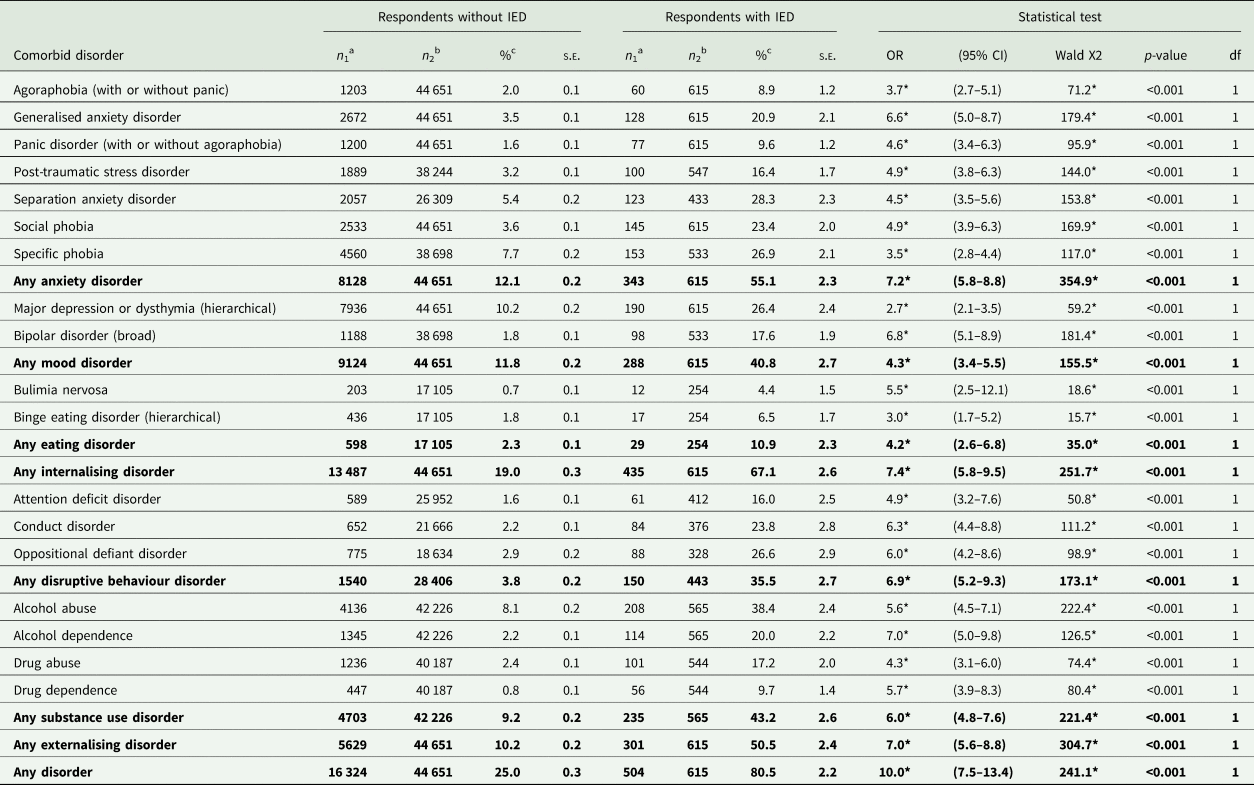

Lifetime comorbidity

The pattern of lifetime comorbidity among those with IED is shown in Table 2, with people without IED (including those without any disorder) as the reference group. Comorbidity rates were high, with 80.5% of those with IED having at least one comorbid disorder, with anxiety disorders being the largest disorder class (55.1%). The percentages reflect, in part, the base rate of the disorders; the odds ratios provide information about the relative likelihood of specific types of comorbidity disorders after taking the base rate into account. From the column of odds ratios we see that internalising disorders were highly comorbid with IED (OR: 7.4; 95% CI: 5.8–9.5); this reflects the high comorbidity with anxiety disorders as a class (OR: 7.2; 95% CI: 5.8–8.8) and with bipolar disorder (OR: 6.8; 95% CI: 5.1–8.9). But there was not high comorbidity with mood disorders as a class, and indeed depression was the specific disorder with the lowest odds of comorbidity with IED (OR: 2.7; 95% CI: 2.1–3.5).

Table 2. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in respondents with or without IED

Logistic regression was used to compare the prevalence of the comorbid disorder in respondents with IED to that in respondents without IED. All analyses control for participants' age, sex, education (in country-specific quartiles) and country of origin. Bold values highlight the results for disorder classes (i,e. groups of disorders).

a Nominator N (number of participants reporting the outcome).

b Denominator N (number of participants asked the question).

c Percentages are based on weighted data.

There was also high comorbidity with externalising disorders as a class (OR: 7.0; 95% CI: 5.6–8.8), due in particular to high comorbidity with the class of disruptive behaviour disorders (OR: 6.9; 95% CI: 5.2–9.3) and with alcohol dependence (OR: 7.0; 95% CI: 5.0–9.8).

In analyses that investigated the temporal ordering of IED and comorbid disorders we found that IED first developed following the onset of the comorbid disorder/s in 61% of cases; conversely, IED was the first disorder to occur in only 29% of cases and first developed concurrently with another disorder 10% of the time. (online Supplementary Table S2).

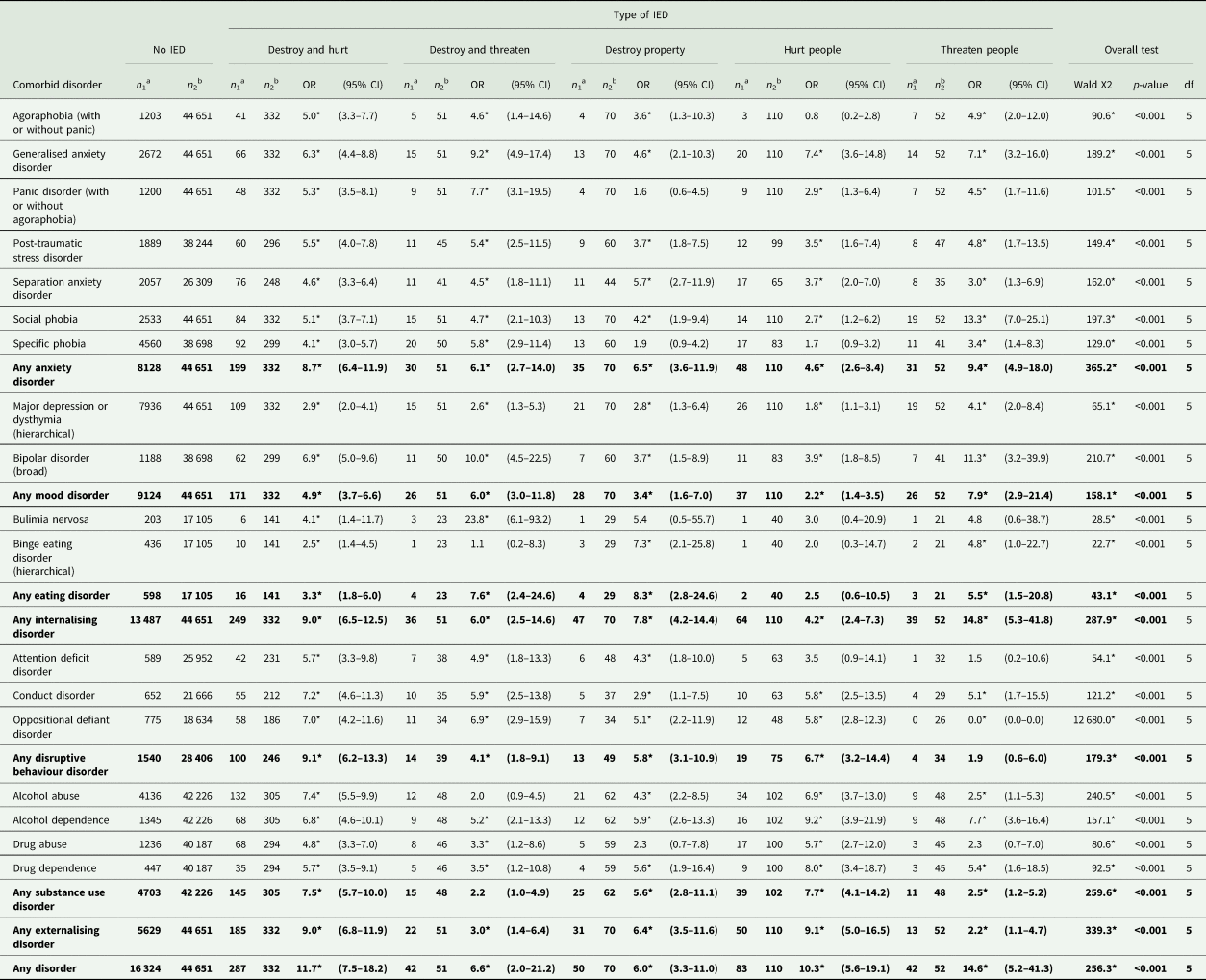

Lifetime comorbidity by IED subtype

Next, we analysed how comorbidity varied by the five IED subtypes, with ‘No IED’ as the reference group (Table 3). The likelihood of having any comorbid disorder (final row of the table) was highest amongst the subtype whose behaviour resulted in the least destruction ('threaten people only’: OR: 14.6; 95% CI: 5.2–41.3), followed by the subtype whose behaviour resulted in the most destruction (‘destroy property and hurt people’: OR: 11.7; 95% CI: 7.5–18.2). The two subtypes characterised by destruction of property but not harm to people had the least likelihood of a comorbid disorder (‘destroy property and threaten people’: OR: 6.6; 95% CI: 2.0–21.2; and ‘destroy property only’: OR: 6.0; 95% CI: 3.3–11.0).

Table 3. Lifetime prevalence of comorbid disorders in respondents with various IED subtypes, compared to those without IED

Logistic regression was used to compare the prevalence of the comorbid disorder in respondents with IED to that in respondents without IED. All analyses control for participants' age, sex, education (in country-specific quartiles) and country of origin. All tests have 1 df unless otherwise noted. Bold values highlight the results for disorder classes (i,e. groups of disorders).

a Nominator N (number of participants reporting the outcome).

b Denominator N (number of participants asked the question).

In terms of the pattern of comorbidity, the two subtypes that involved hurting people (‘destroy property and hurt people’ and ‘hurt people only’) had a substantially higher likelihood of an externalising comorbid disorder than the other three subtypes. The least severe subtype (‘threaten people’) was much more likely to have internalising than externalising comorbid disorders, with an especially high odds of social phobia (OR: 13.3; 95% CI: 7.0–25.1). It is also noteworthy that the two subtypes that involved threatening people (‘destroy and threaten’; ‘threaten people’) had the highest odds of bipolar disorder (OR: 10.0; 95% CI: 4.5–22.5 and OR: 11.3; 95% 3.2–39.9, respectively), although confidence intervals around these (and many of the other) estimates are wide.

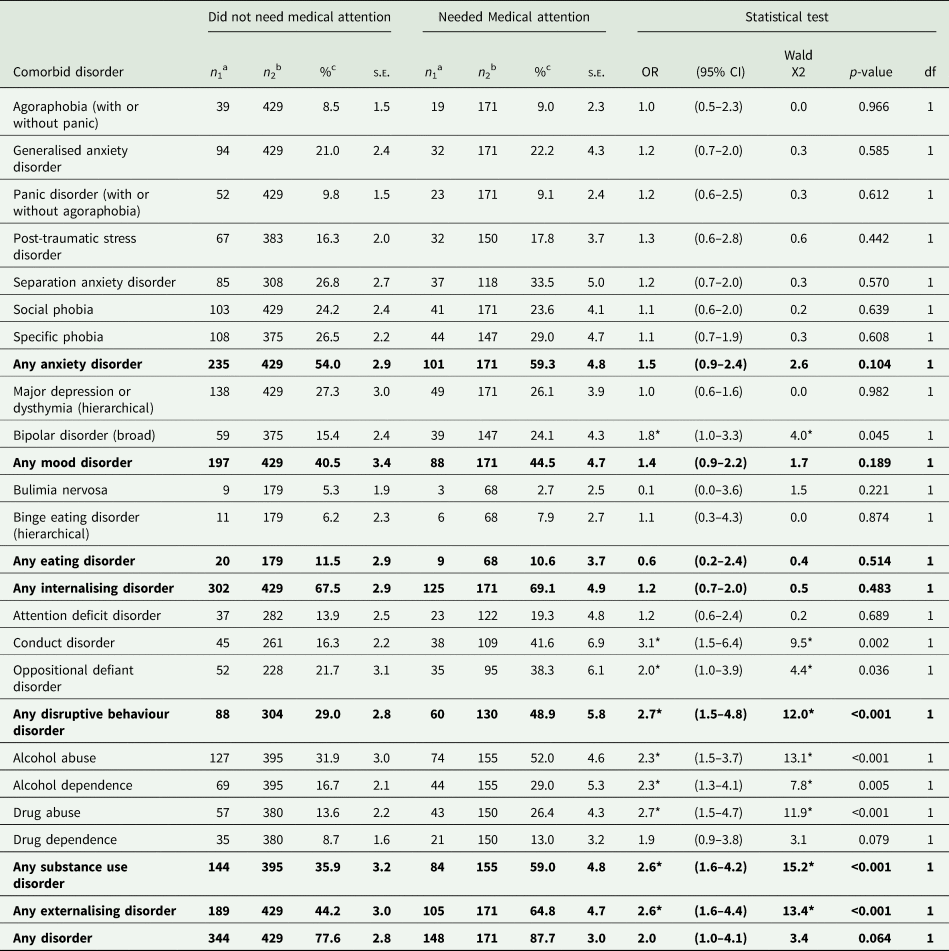

Lifetime comorbidity by severity of violence to others

The next analysis (Table 4) subdivided those with IED into two different groups according to the severity of their violence towards others: (i) those who reported that they had hurt someone so badly they needed medical attention and (ii) all the remaining respondents with IED (reference group). Those whose anger attacks resulted in others needing medical attention were both more likely to have disorder comorbidity overall (OR for any disorder: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.0–4.1) and substantially more likely to have disruptive behaviour disorder (OR: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.5–4.8) and substance use disorder (OR: 2.6; 95% CI: 1.6–4.2) comorbidity relative to the reference group whose violence was less severe. Rates of internalising disorders were fairly similar across the two groups.

Table 4. Lifetime prevalence of comorbid disorders in respondents who have or have never hurt someone so badly they needed medical attention

Logistic regression was used to compare the prevalence of the comorbid disorder. All analyses control for participants' age, sex, education (in country-specific quartiles) and country of origin. Bold values highlight the results for disorder classes (i,e. groups of disorders).

a Nominator N (number of participants reporting the outcome).

b Denominator N (number of participants asked the question).

c Percentages are based on weighted data.

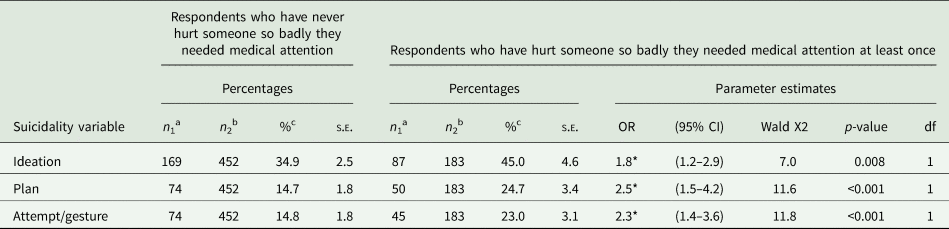

Suicidality

Lifetime suicidal behaviour amongst the total group with IED was 38.1% (s.e.: 2.0) for ideation, 17.6% (s.e.: 1.6) for plan and 17.4% (s.e.: 1.4) for an attempt (online Supplementary Table S3a). When subdividing total IED into those with and without lifetime comorbidity, suicidal behaviour was much lower among the group without comorbidity, with rates of 26.1% (s.e.: 6.3), 3.5% (s.e.: 1.7) and 6.6% (s.e.: 2.4) for ideation, plans and attempts, respectively, compared with corresponding percentages of 40.9% (s.e.: 2.5), 20.5% (s.e.: 1.9) and 19.4% (s.e.: 1.8) in the group with comorbidity (online Supplementary Table S3b).

There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of suicidal behaviour among the five behavioural subtypes (online Supplementary Table S4). When we compared suicidal behaviour between those who did, v. those who did not, hurt someone so badly they needed medical attention, the former group reported significantly more suicidal behaviour than the latter group, in all three suicidal behaviour categories (Table 5).

Table 5. Lifetime prevalence of suicidality in respondents with IED who have or have not ever hurt someone so badly they needed medical attention

Logistic regression was used to compare the prevalence of the suicidality variables. All analyses control for participants' age, sex, education (in country-specific quartiles), and country of origin.

a Nominator N (number of participants reporting the outcome).

b Denominator N (number of participants asked the question).

c Percentages are based on weighted data.

Impairment

The proportion of all those with 12-month IED who reported severe functional impairment in at least one domain (home management, work, close relationships or social life) was 39.8% (s.e.: 3.0); with 44.1% (s.e.: 3.7) among those with comorbidity and 17.1% (s.e.: 6.4) among those without comorbidity (data not shown, available on request). The proportion with severe impairment ranged from 30.9% to 44.5% across the five behavioural subtypes (online Supplementary Table S5); although these differences were not statistically significant.

Discussion

In our first cross-national paper on IED (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Lim, Hwang, Adamowski, Al-Hamzawi, Bromet, Bunting, Ferrand, Florescu, Gureje, Hinkov, Karam, Lee, Posada-Villa, Stein, Tachimori H, Xavier and Kessler2016), we examined lifetime prevalence of comorbid mental disorders among those with IED; the present study builds on that earlier report by examining associations (rather than prevalence) of IED with other lifetime disorders and by investigating whether comorbidity patterns vary by IED behavioural subtypes. The two IED subtypes characterised by acts of aggression resulting in harm to others (collectively comprising 73% of those meeting diagnostic criteria with IED) had a greater likelihood of externalising disorder comorbidity than the other three subtypes, although internalising disorder comorbidity was also prevalent. The least destructive subtype ('threaten only’) had a much higher odds of internalising (v. externalising) disorder comorbidity and high odds of social phobia in particular. After further subdividing those with IED into perpetrators of more v. less violent attacks, we found that the more violent group were more likely to have CD, ODD and substance use disorder comorbidity relative to the less violent group. This more violent group also reported higher rates of lifetime suicidal behaviour (ideation, plans and attempts). There were no significant patterns of variation in functional impairment across IED subtypes.

The major limitations of this study lie in its retrospective assessment of mental disorders. This is known to underestimate lifetime mental disorders (Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, Kokaua, Milne, Polanczyk and Poulton2010; Takayanagi et al., Reference Takayanagi, Spira, Roth, Gallo, Eaton and Mojtabai2014) and to lead to inaccuracies in the age of onset timing (Simon and Von Korff, Reference Simon and Von Korff1995). The retrospective method is likely to make it difficult for respondents to determine whether their anger attacks did or did not occur in the context of other disorders. This is a problem because IED is a diagnosis of exclusion, only made once other mental disorders and personality disorders that could better explain the aggressive behaviour have been ruled out. Of the five disorders found most likely to be comorbid with IED in this study (GAD, bipolar disorder, CD, ODD and alcohol dependence), the latter four are either defined by or strongly associated with aggressive behaviour (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Youngstrom, Steiner, Findling, Meyer, Malone, Carlson, Coccaro, Aman, Blair, Dougherty, Ferris, Flynn, Green, Hoagwood, Hutchinson, Laughren, Leve, Novins and Vitiello2007). This study did exclude from IED diagnosis those who reported that their anger attacks occurred exclusively in the context of depression, substance intoxication or mania, but those with concurrent CD or ODD were not similarly excluded. Moreover, personality disorders were not assessed in enough of the surveys that also assessed IED to assess overlap. As previously reported (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Lim, Hwang, Adamowski, Al-Hamzawi, Bromet, Bunting, Ferrand, Florescu, Gureje, Hinkov, Karam, Lee, Posada-Villa, Stein, Tachimori H, Xavier and Kessler2016), a small proportion of the IED sample admitted to purposely torturing or injuring an animal, or arson, within the prior 12 months, so it is possible that these individuals may be more appropriately classified as personality disordered (or CD) than IED.

Some researchers have chosen to deal with the difficulty of differentiating between IED and bipolar disorder by excluding people with a lifetime history of bipolar disorder from the IED sample (Kulper et al., Reference Kulper, Kleiman, McCloskey, Berman and Coccaro2015; Rynar and Coccaro, Reference Rynar and Coccaro2018; Fahlgren et al., Reference Fahlgren, Puhalla, Sorgi and McCloskey2019). It is unclear why the same theoretical concern does not apply to some of the other comorbid disorders, and if we were to remove all those with lifetime comorbidities associated with impulsive aggression from the group classified with IED we would end up with a much smaller group. It is interesting in this regard to consider the small subgroup of those diagnosed with IED in this study who reported no comorbid disorders. This is a ‘pure’ IED group therefore, whose impulsive anger cannot be attributed to another disorder. We found this group to have much less impairment and suicidality than the bigger group with comorbid disorders. This could suggest that the ramifications of IED for the individual and society are better captured by its comorbid disorders and that the diagnosis of IED per se offers little additional information. On the other hand, comorbidity has generally been found to be a marker for severity of psychopathology, and in the case of IED, it may signify that most sufferers experience such persistent tendencies towards irritable temperament and impulsive anger that these tendencies manifest across several diagnostic boundaries.

Our IED behavioural subtypes were defined on the basis of self-reported behaviour and limited to what was available in the CIDI assessment. The subtypes have not been clinically validated and nor was the diagnosis of IED included in the clinical reappraisal studies conducted as part of the World Mental Health surveys (Haro et al., Reference Haro, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, Brugha, de Girolamo, Guyer, Jin, Lepine, Mazzi, Reneses, Vilagut, Sampson and Kessler2006). The fact that we did not find variation in suicidal behaviour, or functional impairment, across the five behavioural subtypes suggests that they may not capture clinically useful distinctions. It is noteworthy that the two further approaches to subtyping we report herein did result in significant findings related to suicide. That is, we differentiated between those with and without any lifetime comorbidity, and between those engaging in more or less violent attacks, and we did find suicidality significantly higher among those with comorbidity, and among those engaging in more violent anger attacks that resulted in the victims requiring medical attention. From a clinical point of view therefore, these distinctions rather than the behavioural subtyping distinctions may prove more useful.

The findings of this study are inconsistent with prior clinical studies in several respects. Coccaro et al. who have led the clinical research on IED, have conducted a series of studies in which participants responding to advertisements seeking individuals with anger difficulties were diagnosed with DSM-5 IED, other mental disorders, or no disorders. In these studies, the IED group reported greater functional impairment than the ‘other mental disorder’ comparison group (Kulper et al., Reference Kulper, Kleiman, McCloskey, Berman and Coccaro2015; Rynar and Coccaro, Reference Rynar and Coccaro2018), whereas our finding of 39.8% of those with IED reporting severe impairment is lower than the corresponding proportion reported for other mental disorders (Scott et al., Reference Scott, De Jonge, Stein and Kessler2018). In these and in other clinical studies from the same group (Fahlgren et al., Reference Fahlgren, Puhalla, Sorgi and McCloskey2019; Fanning et al., Reference Fanning, Coleman, Lee and Coccaro2019), IED-associated comorbidity was dominated by internalising disorders, in contrast to our finding that comorbidity was at least equally if not more likely to be with externalising disorders. It is notable that in all of the clinical studies females comprised around half of the IED sample (in contrast to our male-dominated general population sample); this raises the possibility that the clinical findings are influenced by gender, help-seeking or other selection biases.

Our findings illustrate the heterogeneity within the diagnostic category captured by the WMH-CIDI for IED. Depending on how the impulsive anger manifested (in particular, whether it resulted in harm to others), type of comorbidity varied considerably. This variation in comorbidity patterning as a function of whether the anger attacks result in harm to others suggests that the present DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, which allow IED to be defined by either high frequency-less destructive acts or low frequency-more destructive acts, will similarly encompass a population that varies substantially in lifetime comorbidity. In this regard, our study findings are consistent with one study from Coccaro's group, which found that comorbidity patterning varied by DSM-5 IED subtypes (verbal aggression only, physical aggression only, or both) (Look et al., Reference Look, McCloskey and Coccaro2015). The implications of this heterogeneity in comorbidity for IED as a diagnostic entity are unclear. While it is the case that several mental disorders are characterised by phenotypic subtypes, the findings presented here suggest that these IED behavioural subtypes are characterised by very different patterns of psychopathology over the life course, such that the disorder becomes difficult to classify as internalising or externalising (de Jonge et al., Reference de Jonge, Wardenaar, Lim, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Andrade, Bunting, Chatterji, Ciutan, Gureje, Karam, Lee, Medina-Mora, Moskalewicz, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Torres, Kessler and Scott2018).

In conclusion, the findings of this study point to a disparity between the comorbidity patterning and impairment associated with IED in population v. clinical studies. This disparity, together with the marked heterogeneity that characterises the diagnostic entity of IED, suggests that it is a disorder that requires much greater research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000517.

Data

The data come from the cross-national World Mental Health Surveys dataset. Due to data-sharing restrictions contained in some individual country agreements with the World Mental Health Surveys Initiative, sharing of the cross-national dataset is not possible.

Acknowledgements

The WHO World Mental Health Survey collaborators are: Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, MD, PhD; Ali Al-Hamzawi, MD; Mohammed Salih Al-Kaisy, MD; Jordi Alonso, MD, PhD; Laura Helena Andrade, MD, PhD; Lukoye Atwoli, MD, PhD; Corina Benjet, PhD; Guilherme Borges, ScD; Evelyn J. Bromet, PhD; Ronny Bruffaerts, PhD; Brendan Bunting, PhD; Jose Miguel Caldas-de-Almeida, MD, PhD; Graça Cardoso, MD, PhD; Somnath Chatterji, MD; Alfredo H. Cia, MD; Louisa Degenhardt, PhD; Koen Demyttenaere, MD, PhD; Silvia Florescu, MD, PhD; Giovanni de Girolamo, MD; Oye Gureje, MD, DSc, FRCPsych; Josep Maria Haro, MD, PhD; Hristo Hinkov, MD, PhD; Chi-yi Hu, MD, PhD; Peter de Jonge, PhD; Aimee Nasser Karam, PhD; Elie G. Karam, MD; Norito Kawakami, MD, DMSc; Ronald C. Kessler, PhD; Andrzej Kiejna, MD, PhD; Viviane Kovess-Masfety, MD, PhD; Sing Lee, MB, BS; Jean-Pierre Lepine, MD; John McGrath, MD, PhD; Maria Elena Medina-Mora, PhD; Zeina Mneimneh, PhD; Jacek Moskalewicz, PhD; Fernando Navarro-Mateu, MD, PhD; Marina Piazza, MPH, ScD; Jose Posada-Villa, MD; Kate M. Scott, PhD; Tim Slade, PhD; Juan Carlos Stagnaro, MD, PhD; Dan J. Stein, FRCPC, PhD; Margreet ten Have, PhD; Yolanda Torres, MPH, Dra.HC; Maria Carmen Viana, MD, PhD; Harvey Whiteford, MBBS, PhD; David R. Williams, MPH, PhD; Bogdan Wojtyniak, ScD.

Financial support

The World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; R01 MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Centre (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc., GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. The Argentina survey – Estudio Argentino de Epidemiología en Salud Mental (EASM) – was supported by a grant from the Argentinian Ministry of Health (Ministerio de Salud de la Nación). The São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey is supported by the State of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) Thematic Project Grant 03/00204-3. The Bulgarian Epidemiological Study of common mental disorders EPIBUL is supported by the Ministry of Health and the National Centre for Public Health Protection. The Shenzhen Mental Health Survey is supported by the Shenzhen Bureau of Health and the Shenzhen Bureau of Science, Technology, and Information. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. Implementation of the Iraq Mental Health Survey (IMHS) and data entry were carried out by the staff of the Iraqi MOH and MOP with direct support from the Iraqi IMHS team with funding from both the Japanese and European Funds through United Nations Development Group Iraq Trust Fund (UNDG ITF). The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013, H25-SEISHIN-IPPAN-006) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs Of the Nation (L.E.B.A.N.O.N.) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), National Institute of Health / Fogarty International Centre (R03 TW006481-01), anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon and unrestricted grants from, Algorithm, AstraZeneca, Benta, Bella Pharma, Eli Lilly, Glaxo Smith Kline, Lundbeck, Novartis, OmniPharma, Pfizer, Phenicia, Servier, UPO. The Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHW) is supported by the WHO (Geneva), the WHO (Nigeria), and the Federal Ministry of Health, Abuja, Nigeria. The Northern Ireland Study of Mental Health was funded by the Health & Social Care Research & Development Division of the Public Health Agency. The Peruvian World Mental Health Study was funded by the National Institute of Health of the Ministry of Health of Peru. The Polish project Epidemiology of Mental Health and Access to Care –EZOP Project (PL 0256) was supported by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through funding from the EEA Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism. EZOP project was co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Health. The Portuguese Mental Health Study was carried out by the Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medical Sciences, NOVA University of Lisbon, with collaboration of the Portuguese Catholic University, and was funded by Champalimaud Foundation, Gulbenkian Foundation, Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) and Ministry of Health. The Romania WMH study projects ‘Policies in Mental Health Area’ and ‘National Study regarding Mental Health and Services Use’ were carried out by National School of Public Health & Health Services Management (former National Institute for Research & Development in Health), with technical support of Metro Media Transilvania, the National Institute of Statistics-National Centre for Training in Statistics, SC, Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands and were funded by Ministry of Public Health (former Ministry of Health) with supplemental support of Eli Lilly Romania SRL. The South Africa Stress and Health Study (SASH) is supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059575) and National Institute of Drug Abuse with supplemental funding from the South African Department of Health and the University of Michigan. Dr Stein is supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa (MRC). The Ukraine Comorbid Mental Disorders during Periods of Social Disruption (CMDPSD) study is funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (RO1-MH61905). The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708) and the John W. Alden Trust. None of the funders had any role in the design, analysis, interpretation of results, or preparation of this paper. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of the World Health Organization, other sponsoring organisations, agencies or governments.

Conflict of interest

Ron Kessler:

In the past 3 years, Dr Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis; was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, Sage Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Takeda; and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research.

Dan J. Stein:

In the past 3 years, Dr Stein has received research grants and/or consultancy honoraria from AMBRF, Biocodex, Cipla, Lundbeck, National Responsible Gambling Foundation, Novartis, Servier and Sun.

All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.