The Lukaya billboard

I am fascinated by a billboard that stands close to the Lukaya Bridge, which spans the River Katonga on the main road between Kampala and Masaka – which is also the main trunk route from Uganda's capital to its south-western regions and to Rwanda, and, beyond that, to the Democratic Republic of Congo (Figure 1). The billboard, which was built in late 2007, is floodlit, stands more than six metres high, and displays two images of President Yoweri Museveni in conversation with the former Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. Below the pictures, a caption reads, in both English and Arabic: ‘Brother Leader Muammar Al Qaddaffi and president Yoweri Museveni of Uganda in Luwero Triangle, 150km north of [the] capital city Kampala. Around this triangle, Libyan Air Force[s] dropped – in 1985 – weaponry which proved in favour of the National Resistance Movement in Uganda.’ In these ways, then, the billboard is very clearly intended to be a public monument to what were, at the time of its construction, the intended deepening bilateral ties between Kampala and Tripoli.

Figure 1 The Lukaya billboard.

What interests me most about the Lukaya billboard are three features of its semiotics and of its social biography. The first is that, although the billboard's caption offers an unequivocally historical narrative, its images are in many ways oriented primarily towards the future. By casting Gaddafi as Museveni's superior – given that he is the dignitary here, the one being shown around by Museveni – both of the billboard's pictures reference the Libyan president's then active plan for Africa's future. This plan involved the African Union (AU), an institution that Gaddafi had helped to set up, becoming gradually transformed into a single, sovereign nation state, over which the Libyan leader would preside. The billboard was in fact put up just a few weeks after an AU summit in which Gaddafi had convinced a number of traditional leaders from across the continent to declare him Africa's ‘king of kings’ (de Waal Reference de Waal2013: 367). By casting both presidents as ‘forward looking’ – in the right-hand frieze in particular, both men's gazes are fixed firmly into the middle distance, while in both pictures Museveni points far away – the billboard also references a potential future role for Museveni himself, and for Uganda as a whole, within this wider project. By the time the billboard was put up, Museveni had expressed scepticism at Gaddafi's idea of full political unity across the continent, as a full ‘United States of Africa’. However, he was also making regular speeches about how Uganda would benefit developmentally from further economic and social integration across the continent (Baligidde Reference Baligidde2012), and it was being rumoured that he had even begun to position himself as a potential successor to Gaddafi at the head of a future Pan-African project. Yet it is not only the semiotics of this photographic monument that hint at the future; so too do elements of its social biography. Of particular note is the story of the billboard's unveiling – or, more accurately, its lack of unveiling – during a state visit Gaddafi made to Uganda in March 2008. During that visit, Gaddafi closed the first African-Arab Youth Summit and officially opened the incredible ‘Gaddafi National Mosque’ in Kampala. On the last day of his visit, he was due to officially unveil the Lukaya billboard (which until that point had been covered by a large tarpaulin). The visit had been a tense one, not least because the two presidents’ respective security contingents had clashed during the unveiling ceremony for the mosque.Footnote 1 However, in a portent of what was to become Gaddafi's ultimate fate, what finally forced the Libyan leader to cut short his stay to Uganda were the first stirrings of political unrest in Benghazi. It was because of this that the Lukaya billboard was never, in fact, officially unveiled.

The second feature of the billboard that interests me, and one that is connected to the first, is its use of post-photographic techniques, especially ‘photoshopping’, to achieve its projection of the future. The fact that both of these pictures are heavily photoshopped is already betrayed by their incorrect scale and inconsistent perspective, and by the heavy shadowing behind the figure of Museveni in the right-hand scene. In addition, Colonel Gaddafi's face has been ‘touched up’ to remove blemishes, while the images of Museveni are of the Ugandan president in his younger days (by my estimate, both pictures show the Museveni of the late 1990s). However, of particular relevance is the use of photoshopping to alter the landscapes that appear in the background of the two pictures. On the one hand, post-photographic techniques have resulted in these landscapes being a pastiche of the Ugandan countryside. Thus, although the billboard's caption refers to the Luwero Triangle, the landscape in the left-hand image instead shows the hills of Uganda's far south-west, while the background in the right-hand image displays the iron sheeting of Lukaya Bridge itself, but this is depicted in front of hills that are almost certainly neither Lukaya nor Luwero. On the other hand, and of greater relevance for my argument here, photoshopping is also used to project a vision of how a future development might transform the Ugandan countryside. This is particularly marked in the image on the right, in which a line of electricity pylons and four industrial fuel silos have been photoshopped onto the landscape (the latter of which also reference the then recent discovery of significant oil reserves in Uganda's Lake Albert region (Vokes Reference Vokes2012a)).

The third, and final, feature of the Lukaya billboard that is of interest to me here relates less to its semiotics than to its social biography as a photographic monument, and to the way in which this later became implicated in what, following Pype, I will call a public ‘politics of affect’ (Reference Pype and Vokes2012). It is important to recognize here the extraordinary levels of public excitement that Gaddafi's at one time frequent visits to Uganda used to generate. This excitement – which was partly a result of sensationalist media coverage and partly an outcome of Gaddafi's own pomp and performance during his visits – would often result in thousands of people lining the streets of Kampala and other urban centres to greet his convoy, often in a state of great anticipation. For example, I keenly recall witnessing one official visit by the Libyan leader to Uganda in July 2001, when, following extensive media coverage of the preparations that had gone into the visit – such as flying in an armoured Mercedes-Benz from Tripoli – and lurid reportage of Gaddafi's corps of female bodyguards who accompanied him on the trip, many thousands of Ugandans lined the main Entebbe–Kampala Road to witness the Libyan leader's reputedly mile-long convoy passing by. At one point, Gaddafi emerged through the sunroof of his car and began throwing bundles of cash, gold jewellery and other valuables into the crowds, in an action that not only generated an extraordinary collective excitement but very nearly caused a stampede. Moreover, it was not only those who witnessed the convoy in person who engaged in this collective outpouring of emotion. Even in the remotest rural areas, people excitedly engaged with the visit through media outlets and through the huge market in photographic prints of the Libyan leader that grew up around the visit (at one stage, this market became so large that photographs of Gaddafi became a common feature in all kinds of personal photograph albums throughout the country). Interestingly, when I later asked people what it was about Gaddafi's visits specifically that generated quite so much interest and engagement – the likes of which I have never witnessed during the visit of any other foreign dignitary to Uganda – my respondents invariably made sense of it through reference to the feelings of optimism that Gaddafi inspired for Africa's future. As one of my respondents succinctly put it: ‘What we like about Gaddafi is that he shows us what we Africans could become. He shows us that we too could become rich, and proud, just like the Europeans.’ In this context, there can be little doubt that at least part of Museveni's motivation for commissioning the Lukaya billboard – which stands beside the busiest intercity highway in Uganda – and for holding a major ceremony for its unveiling was to harness at least some of this wider public excitement and optimism for his own ends. In other words, there can be little doubt that the Ugandan president – whatever his misgivings about the Libyan leader's wider political project (and reportedly his growing personal antipathy towards the man)Footnote 2 – saw in Gaddafi's fame an opportunity to forward his own political project as well. All of this is totally in keeping with Museveni's political biography as an arch-populist and as a master in manipulating collective political affect.

However, if this was Museveni's intention in constructing the billboard, then, like all of the other visions for the future that I have described here – Gaddafi's United States of Africa, Museveni's emerging continental leadership, and so on – it never came to pass. Instead, following the overthrow of Gaddafi in 2011, all of these things became forever trapped in what, to borrow a linguistic metaphor, might be described as a ‘historical future tense’. Nevertheless, even after 2011, the Lukaya billboard did generate a significant public response – just not one that the Ugandan president would ever have intended.Footnote 3 Instead, from that time onwards, the Lukaya billboard became widely interpreted as a monument to Gaddafi's extraordinary political hubris, and, by a short extension, to Museveni's as well. As such, it never failed to generate animated discussion, and both anger and laughter in equal measure, among all those who drove past it. By early 2012, it had even become a common practice for passing motorists to stop at the site and, in acts of satire, to take selfies in front of it, in which people invariably pulled a funny face or struck a ludicrous pose. So concerned did the authorities become about these practices that for several years afterwards they located both an army post and a police station directly underneath the billboard, with orders to arrest anyone who even stopped at the site, let alone tried to take a photograph there.

An emergent public visual culture

This extended exposition of the Lukaya billboard serves as a good introduction to this article, which contributes to our understanding of a new public political visual culture that has emerged in Uganda – and across Africa, and beyond – over the past decade or so. This culture is characterized by an extensive use of post-photographic techniques (including both photoshopping and computer-generated imagery or CGI) to present visions of official developmental and political goals, and it appears to frequently draw a strong affective response from its citizen viewers. Billboards are an obvious starting point from which to explore this nascent visual culture, given that they are the medium through which it first emerged, and given that it is through billboards that a majority of Africans continue to see, and to engage with, its imagery; this is itself a reflection of the fact that, as with the Lukaya example, political billboards tend to be sited on major thoroughfares or in other significant public places. However, this new public political visual culture also now extends to many other kinds of visual media, as the pictures that may have first appeared on billboards have been reproduced – and/or have given rise to the use of other, similar images – within official policy and planning documents, government departments’ promotional posters and leaflets (which, in Uganda at least, are typically circulated as glossy newspaper inserts as part of the launch of any major policy document or large-scale development projects), and all kinds of official and ‘public–private’ websites, for all kinds of current and future projects.

To begin with billboards, in recent years a growing number of scholars have begun to examine the ways in which governments throughout Africa, and beyond, have recently made an increasing use of these public signs to project images of aspirational development projects. To date, much of this scholarship has focused especially on official billboards that are located in and around large cities, and which therefore project images of specifically urban redevelopment schemes – such as the aim to transform a section of the city through the construction of new tower blocks, parks and lawns, urban transport infrastructure, and so on. For example, Filip De Boeck and Katrien Pype have both described how Congolese president Joseph Kabila has sited billboards across Kinshasa as a means to display the future benefits of his proposed ‘Cinq Chantiers’ programme of public works – which comprise housing, roads, electricity infrastructure, educational facilities and hospitals (De Boeck Reference De Boeck2011; Pype Reference Pype and Vokes2012). Samuel Shearer has examined how the Rwandan government has placed billboards at strategic sites around Kigali in order to project images of the city's fifty-year ‘master plan’, which envisages major transformations of the Rwandan capital's residential, public and commercial built environment (Reference Shearer, Isenhour, McDonogh and Checker2015; see also Doherty Reference Doherty2013). And Vanessa Watson has described similar government-funded, or public–private, visual displays in Accra, Ghana; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Lagos, Nigeria; Luanda, Angola; and Nairobi, Kenya (Reference Watson2014). In all instances, the images that appear on these billboards are heavily photoshopped and/or make extensive use of CGI, and they are also reproduced in official documents, through news outlets and on the internet.

In all of these examples, the semiotics of these public displays are in fact remarkably consistent. As with the Lukaya billboard, they all focus on desired African futures, which are cast in terms of current imaginaries about transnationalism and globalization. In this way, not only do all of the billboards’ post-photographic future African cityscapes bear an obvious general resemblance to existing centres of global capital such as Dubai, Hong Kong or Shanghai – with their ‘Corbusian modern[ist]’ architecture of glass tower blocks, geometric roads and manicured gardens (to paraphrase Watson Reference Watson2014: 215) – but their photoshopped pictures may even incorporate buildings, architectural motifs or additional features from those other places. For example, Watson notes that one of the billboards for the Kigali master plan included a picture of London's iconic skyscraper the ‘Gherkin’ (ibid.: 217), while I have observed that one of the public signs associated with Uganda's current national development plan, ‘Vision 2040’, pictures a Dubai airport train travelling through central Kampala.Footnote 4 Another billboard, for the country's new Kampala–Entebbe highway, simply shows a UK motorway photoshopped onto an image of a Ugandan landscape. Indeed, the billboards’ images may on occasion become so saturated with the signs and symbols of an imaginary ‘global modernity’ that it is only through the incorporation of an iconic feature of the local landscape or built environment – such as the Congo River in Kinshasa (De Boeck Reference De Boeck2011), Mount Kigali (Shearer Reference Shearer, Isenhour, McDonogh and Checker2015), or Workers’ House in Kampala (in my examples) – that one is able to decipher to which city the picture is actually meant to refer. Yet, as with the Lukaya example, this peculiar combination of features may also lend the images an element of pastiche.

In addition, and like the Lukaya billboard, these projected futures can again be interpreted in terms of the ways in which they forward their creators’ current political ambitions. Thus, the Kinshasa billboards’ futuristic imagery serves to render visible President Kabila's political programme, which aims for nothing less than ‘Congo's reinsertion into the global oecumene’, and for the country to once again become a ‘mirror of modernity’ – although this time one that ‘no longer reflects the earlier versions of Belgian colonial modernity, but instead … the aura of Dubai and other hot spots of the Global South’ (De Boeck Reference De Boeck2011: 274). De Boeck notes that a presidential quote about the Congo becoming ‘the mirror of Africa’ is even used to caption a number of the images. Similarly, the billboards of Kigali, in their projection of the city as a future ‘Singapore of Africa’, reference President Kagame's overarching political project, which revolves around his forging of a ‘post-genocidal state’ in Rwanda – a project that has long been characterized by an erasure of the specificities of place and history in the country (Pottier Reference Pottier2002) and which has both fed into and fed off a ‘collective ambition to reinvent Kigali's future as somewhere else’ (Shearer Reference Shearer, Isenhour, McDonogh and Checker2015: 183). Since 2000, a key component of this project has been a macro-economic policy based on the ‘East Asian Tiger’ model of growth – which, by potentially generating financial ‘take-off’, offers the promise of an economic break with the past as well (ibid.). So, too, the billboards of urban Ghana, Tanzania and Nigeria can also be read as projections of those states’ development programmes – programmes that, although they vary in detail from country to country, are driven everywhere by an aspiration to vastly increase foreign direct investment (FDI), following the interventions especially of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In this reading, it is noteworthy that the billboards’ images were in many cases initially generated for African governments by international commercial property companies, firms that often retain an ongoing stake in the projects themselves (Figure 2). It is also relevant that the billboards’ fantasy landscapes may also invoke a global capitalist discourse about ‘Africa rising’ – which is best understood as a marketing ploy designed to attract global investors into what remain high-risk property markets (Watson Reference Watson2014: 215–16). Yet in all of these ways, and for all of these scholars, the billboards present visions of the future that are likely to be, ultimately, highly exclusionary. On the one hand, the anticipated benefits of vastly increased ‘globalist capitalist flows’, even if these ever occur, will likely only advantage a very narrow elite of urban residents. In other words, the images’ ‘luxury’ apartment blocks and other amenities, if built, will be unaffordable – even inaccessible – for the vast majority of people who currently live in Kinshasa, Kigali or Accra (i.e. for a vast majority of the billboards’ viewers). On the other hand, the billboards’ future projects will involve, and in some cases already have involved, the clearing of broad swathes of urban land – land on which large numbers of people currently live, work and socialize. For this reason, all of these visionary estates can also be understood as extending an existing ‘hard-handed politics of erasure’, which in many African cities, and for a wide range of political motivations, regularly involves ‘destroying “irregular”, “anarchic” and unruly housing constructions, bulldozing bars and terraces considered to be too close to the roadside, and banning containers, which [residents] commonly convert into little shops, from the street’ (De Boeck Reference De Boeck2011: 272).Footnote 5

Figure 2 An image of a future Kampalan cityscape at Nakawa-Naguru.

Yet, and again as in the Lukaya example, these other billboards’ political implications also extend beyond just the semiotics of their imagery to additionally include the effects – and affects – that they may produce as material objects. This point is developed most fully by Katrien Pype, for whom Kinshasa's billboards become nothing less than a key physical site through which ‘political power penetrates daily life’ (Reference Pype and Vokes2012: 189). Pype's argument begins from the recognition that these public visual displays, like all other kinds of photographic image objects, may elicit not just an optic but also a ‘haptic’, or tactile, response from viewers. In relation to President Kabila's billboards for the Cinq Chantiers specifically, this potential is then deliberately exploited by the designers in ways that result in displays not only encouraging ‘intellectual reflection’ but also ‘awaken[ing]’ and ‘transmitt[ing]’ political sentiments. In particular, the ubiquity of these billboards throughout the urban space, by establishing Kabila's ‘visibility’ (la visibilité), aims to inculcate general feelings of confidence that the president is in control (ibid.: 201). The billboard's utopian futuristic landscapes are thus designed to stimulate a specific sense of trust – in the leader's ability to guide the country into a successful future. If these are the designers’ intentions, then the success of their project is attested to by the manner in which political billboards may ‘influence the ways in which people move’ through Kinshasa, as they, for example, stop at a billboard to reflect on its vision, debate a billboard's meaning during a taxi ride, or go via a billboard to attend its unveiling ceremony (ibid.: 189). Their success is also demonstrated by the manner in which the billboards’ projections may be greeted with a general sense of enthusiasm and desire, sometimes even among people who are fully aware that they might be forcibly relocated if the projects were to go ahead (an apparently perverse response that is also noted in De Boeck Reference De Boeck2011). However, as with the Lukaya billboard, this kind of political affect remains inherently unstable. This much is evidenced by Pype's description of how Kabila's billboards went on to become a key focus for anti-government sentiment during Congo's (highly contested) presidential election campaigns of 2006. For example, she describes how during one opposition rally, the crowd systematically tore down or defaced as many Kabila posters as they could find – having been moved by them to a state of collective ‘fanaticism’ – (ibid.: 197–8, emphasis added; for another example, see Pype Reference Pype2013: 62–3).

In relation to this broader body of scholarship, the argument of this article is threefold. Firstly, it argues that in Uganda's case at least, although this new public political visual culture is in some respects innovative, in others it can be seen as an extension of two long-established modes of representing official aspirations in the country. One of these modes can be traced back to the advent of colonial rule in Uganda, and the other to the emergence of the country's contemporary ‘developmental state’ following the end of the civil war in 1986. Second, the article suggests that, although Uganda's new visual culture began with public billboards located in urban areas and on major intercity thoroughfares, the more recent reproduction of its imagery in an increasingly wide range of media – including state planning documents, official leaflets and government-sponsored newspaper inserts – is of greater significance for understanding its ongoing, and indeed growing, political force. This process of reproduction has made the imagery both more mobile and more easily mediated (including on social media and the internet), and, in so doing, it has given it a much broader reach and has enabled people to consume it in a wide range of new ways. Third, and linked to this, the article also argues that, in contrast to earlier readings of Africa's new public visual culture as inherently exclusionary, a study of these newer circulations reveals that much of its potency stems from the promise that the benefits of an emergent global capitalism will be available to all citizens of Uganda. The article will substantiate this latter point through an ethnographic study of the social biography of the ways in which this imagery worked in the run-up to the 2016 general elections.

Signs of development

In tracing the historical antecedents of Uganda's new public political visual culture, there are two key trends to be highlighted. The first relates to the ways in which, from the establishment of colonial rule onwards, successive administrations often used photography as a means for making visible their future goals for the country. Most notably, from the time when Europeans first arrived in the late nineteenth century, they frequently employed or commissioned photographers to extensively picture official opening ceremonies, new civic buildings and modern institutions (such as schools, hospitals and prisons), and other ‘examples of “progress”’ (Buckley Reference Buckley2010: 147; cf. Vokes Reference Vokes and Vokes2012b). As I have documented at length elsewhere, the colonial administration, throughout the first half of the twentieth century, also held regular public exhibitions to demonstrate its future plans for agriculture, health, housing and/or industry in which photography played a key part. Specifically, these exhibitions’ displays of ‘model’ futures would be almost always extensively photographed, and the resulting images converted into official albums that could be circulated to local government officials throughout the country as a means of increasing the exhibitions’ reach. Later, the British authorities, in 1947, set up a dedicated Photographic Section, whose job it was both to coordinate and to expand this kind of exhibition photography, and also to visually document the government's then rapidly growing industrial ‘modernization’ programmes (see especially Vokes Reference Vokes2010a; Reference Vokes2018). Uganda's first postcolonial administration, that of Milton Obote, continued to employ what remained of the section in similar ways, while the following regime, of Idi Amin, vastly expanded its operations as a way of documenting his administration's future goals (although under Amin's rule, the relationship between the state and imagery/media in general also became more complicated in various ways; see Peterson and Taylor Reference Peterson and Taylor2013).Footnote 6

However, after the overthrow of the Amin regime, and the period of political turmoil and state collapse that followed, by the time the National Resistance Movement (NRM) came to power in 1986, the ability of the government to use photography in this way had been severely curtailed. Simply put, although from the earliest days of the Bush War onwards the NRM had patronized a small cadre of photojournalists both to document the military campaign and to depict the ‘new society’ it planned to build once in power, the Museveni government no longer possessed the kind of institutional infrastructure necessary for systematically deploying photography as part of its wider state (re-)building programmes. However, this is not to say that the new government was not keen to find ways of ‘rendering visible’ its aspirations for its new – donor-led – ‘developmental state’, nor that it was unaware of the political potential for doing so. Rather, from the time the NRM took power, the authorities instead insisted that every new development programme or project begun in the country should first put up a public sign to announce its goals, and that at the outset of the programme/project an official ‘unveiling ceremony’ should be conducted for its sign. The result was that, within a short period of time, thousands of these signs had been put up all over the country, and although they were to some degree more concentrated in urban areas than rural ones, it was also the case that throughout the 1990s practically the entire landscape of Uganda came to be dotted with these visual artefacts – the vast majority of which were placed in roadside locations to maximize their public impact.

Although the precise dimensions and style of these signs varied from place to place, in most instances they followed a series of conventions that can ultimately be traced back to the period of post-World War Two ‘modernization’. The vast majority of the new NRM-era signs stood between ten and twelve feet high and followed a standard format, in which a series of horizontal text panels (between six and eight) were used not only to announce the planned development outcome but to do so in a way that presented it as an act of nation building and as a hierarchical intervention that ‘flowed downwards’ from the government, through a series of mediators, to ordinary citizens (Figure 3). These latter effects were achieved by the placement of Uganda's national coat of arms at the top of the sign – this was usually also the sign's only icon – and in the ordering of the panels, which generally started at the top with ‘The Republic of Uganda’ (and sometimes also a national ministry) and then moved downwards through ‘The Funding Agency’ (usually an international donor), ‘The Manager’, ‘The Project’, and finally ‘The Contractor’ (i.e. the organization or company that was actually delivering the work).

Figure 3 Example of a development sign.

However, in order to understand the role that these signs have played in furthering the NRM's nation-building project, it is necessary to examine not just their semiotics but also how they became implicated, as visual artefacts, in a future-oriented ‘politics of affect’. Take, for example, one particular sign that stands close to the small town of Buteraniro, which lies on the same highway as the Lukaya billboard (although some 200 kilometres to the west of it). Unlike the Lukaya billboard, this particular sign is visually nondescript, not least because it follows precisely the format outlined above in its announcement of a major state- and Ministry of Agriculture-led scheme for improving agricultural inputs (seedlings, fertilizers and machinery). The sign is old now, its paint weathered, its frame and boards rusted, and its text badly faded. Nevertheless, it has had a rich social biography, having long acted as a focus for political aspirationalism in this locality. For instance, when the sign was first put up, in early 2001, it became the subject of not just one but three ‘opening ceremonies’ during which a series of senior government figures presented it – in the context of the general election campaigns of that year – as material evidence of the kinds of transformations that NRM developmentalism was bringing. I especially recall one of these ceremonies, which was presided over by the local MP of the time, Eriya Kategaya;Footnote 7 held on the weekly market day in the town, it was attended by several thousand people. One aspect of the event that particularly struck me was the degree to which, during his main speech on the new project, Kategaya developed a markedly ‘embodied engagement’ with the sign, not only by pointing at it throughout and also by frequently touching it, but at one stage even by slapping it vigorously in order to emphasize a point. At the end of the ceremony, Kategaya and the other dignitaries posed in front of the sign – indeed, for more than an hour – while a cadre of local paparazzi took their photographs (for more on the activities of these paparazzi, see Vokes Reference Vokes and Vokes2012b). If all of this generated a general sense of excitement in relation to the future benefits of the proposed project among the gathered crowd, then this was further stoked by Katageya's final act of the day, in which he provided a lunch (kyamushana) of bananas, potatoes and beans for the entire audience – a huge, and obviously highly costly, undertaking. In so doing, it was almost as if the MP ‘made manifest’ the content of the speech he had just given on the future benefits of the agricultural project – a large part of which had focused on the way in which it would massively increase agricultural output.

However, as with the Lukaya billboard, so too did the Buteraniro sign's promised future never come to pass; as is so often the case with this kind of development signage across Uganda, the project to which it referred was never implemented (or at least not in any way that was evident to Buteraniro's residents). As a result, by the time of a later period of my fieldwork, in early 2004, many people in the area were expressing their disgruntlement not only with the prospects for this particular scheme, but with the wider developmentalism that it represented. These sentiments became manifest through people's embodied engagements with the physical artefact itself. Therefore, on this visit, I noted that people were frequently stopping at the sign to insult it as they walked past; on two occasions, I witnessed women casually kicking it, and one night I even watched as a group of inebriated young men, on their way home from a bar, pelted it with stones. Eventually, the local chief of police was forced to issue a warning against any further acts of vandalism. Yet even after such incidents had apparently ceased, the sign continued to act as a fulcrum for a kind of political aspirationalism that draws on affect. For example, during a further period of fieldwork, in mid-2015, I attended another rally at the sign, this time held by an aspiring MP (who ran in the parliamentary elections the following year). On this occasion, the main speech again focused on future development, although this time framed as a set of outcomes that only he, the candidate, could possibly deliver. Once again, though, I was particularly struck by the manner in which, throughout the talk, the candidate developed a markedly embodied engagement with the sign itself – by once again frequently pointing to it and touching it, and also by displaying what I can only describe as a kind of physical rage as he mused on what he described as the sign's ‘lies’ (bibeiha). Finally, at the end of his speech, he brought forward a European ‘consultant’, a young German man, who began a procession away from the sign – which the entire crowd, in a state of collective enthusiasm, joined – to begin ‘measuring up’ for the candidate's own alternative project. It was later widely rumoured that this so-called ‘consultant’ was in fact an imposter – simply a tourist whom the candidate had hired for the day in an act of political theatre. Nevertheless, the sense of general optimism that the candidate's rally generated lingered for some time afterwards.

Imaging the future

Against this background, Uganda's new political billboards, which proliferated from around the late 2000s onwards, could be interpreted as simply the coming together of these two long-standing trends. In other words, these more recent public visual artefacts could be seen as simply the latest attempt by the Ugandan state to use photographic imagery as a means to project its future goals, this time by incorporating such imagery within the medium of development signage. And, indeed, the earliest examples of these billboards – and some later ones as well – betrayed this dual heritage directly by positioning their images of the future on one side (usually the left-hand side), opposite blocks of text that directly reproduced the visual structure of the development signs (Figure 4). In this reading, then, the new billboards’ main innovation was their use of post-photographic techniques (photoshopping and CGI) to present increasingly fantastical images of the future. However, in trying to understand the political potency of this new public visual culture, I would argue that there is also more to it than that. Of equal importance in Uganda's case is the way in which, in recent years, in the context of the country's upsurge of spending on major infrastructure projects, the imagery of this new visual culture has increasingly been reproduced within other, more mobile media as well (described above), which quickly resulted in it having an even more direct impact on ordinary people's personal lives throughout the country.

Figure 4 A recent sign for the refurbishment of the Kabaka (King) of Buganda's palace in Mengo, Kampala.

In recent years, the pace of the Ugandan government's spending on new infrastructure projects has quickened considerably. Especially since 2013 – the year in which Museveni launched his latest, and by far his most ambitious, national development plan, ‘Vision 2040’ – the government has secured billions of US dollars’ worth of new external funding for investment in major upgrades to Uganda's water, energy, communications and transportation (road and rail) infrastructure. Much of this new money has come in the form of concessionary loans – so-called ‘soft loans’ – especially from China, and at least some of these loans have been guaranteed against Uganda's anticipated future oil wealth from the Lake Albert basin (see Vokes Reference Vokes2012a; Reference Vokes2016). It has also included new aid streams, especially from the World Bank and the European Union, and new private investment, much of which has been secured under new ‘public–private partnerships’ that are again linked to the nascent petrochemical industries. These huge volumes of new inward funding, and the infrastructural spending that they allow, are likely to continue for at least another decade, following the IMF's recent endorsement of a plan for the Ugandan government to raise an additional US$11 billion for infrastructure by 2025. As might be expected, the government's spending on new infrastructure projects has been highly uneven across the country, as a result of which different regions have benefited from the spending or have missed out to varying degrees. However, for those parts of the country that have seen major new investments, the emerging infrastructure projects have not only generated a renewed wave of popular optimism in President Museveni's nation-building project but have also begun to bring direct material benefits for a significant number of people – with the promise of more to follow. And my argument is that if all of this has generated a more general sense of optimism for the country's future, then this has also been greatly amplified by the futuristic photoshopped and CGI-rich imagery that has been circulated as part of the infrastructure projects themselves.

Take, for instance, a series of new infrastructural projects that have recently begun in the Rwampara Hills, which lie to the east of Buteraniro and which have been my main field site in Uganda since 2000.Footnote 8 In Rwampara's case, recent major public investments relate to a large rural electrification scheme, which was rolled out in 2014, and to a series of major upgrades to various roads – including to one major trunk route – from 2015 onwards. The Kampala–Kigali branch of the regional standard-gauge railway network is also planned to pass through Rwampara – although work on that line is still some years away (if it happens at all). The key point, though, is that unlike the projects undertaken earlier in the NRM era, which might have taken months or years to produce any significant visible outcomes (if they ever did),Footnote 9 with all of these newer infrastructure projects, their results became obvious more or less straight away. Moreover – and more importantly – these newer projects also brought direct, and concrete, benefits to ordinary people living alongside them from the outset – especially in the form of compensation payments (okurihirira). Indeed, not only were compensation payments routinely made as part of the planning process for all of these infrastructure projects, but these became a key means through which the state could pay (often sizeable) sums of money directly into households.

For example, in relation to Rwampara's recent rural electrification, part of this project involved the construction of a new power line along the rural roads running through the area, a line that was held up by wooden poles sited thirty metres apart, with transformer units placed at regular intervals. According to a range of testimonies that I gathered during fieldwork in the area in 2015, a few days before the line was due to be constructed, a small team of officials and engineers arrived in the village, unannounced, to map out where the poles and transformers were to be placed. Where these locations were sited on households’ private land, the team handed out, on the spot, cash compensation payments of 1,000,000 Ugandan shillings per pole and 3,000,000 per transformer unit. Significantly, because a majority of households here sit alongside the road (Vokes Reference Vokes2007), almost all of these fixtures were sited on private land, as a result of which virtually every household in the village ended up benefiting from the compensation. Indeed, some households became fabulously rich overnight. For instance, I recorded one case in which this compensation was paid to the households of three brothers who lived next to each other. Across their combined land were placed four poles and one transformer unit, as a result of which their extended family received, in one morning, 7,000,000 Ugandan shillings – roughly equivalent to five and a half years of wages for an average agricultural labourer. In relation to the larger road upgrades on a nearby trunk route, the range of compensation payments was much wider, and the sums involved far larger. In that case, and as I later recorded in relation to one trading centre that sits on that road, a few weeks before construction began, a survey team again arrived in the vicinity, this time to determine where the boundaries of the ‘road reserve’ lay (i.e. the boundaries of the works area). Wherever the road reserve encroached upon a private property by at least one metre, then the owner was entitled to receive compensation equal to the market value of their entire property. Once again, many of the properties here sat alongside the main road, as a result of which many would likely have received this compensation.Footnote 10

The key point here is that, shortly before the start of each of these projects – the rural electrification scheme and the nearby trunk road upgrade – development signs of the sort described (i.e. with a post-photographic image of the future project on one side and the standard blocks of text on the other) were first erected and became the focus for a series of elaborate opening ceremonies. However, unlike the Buteraniro project described above, with both of these schemes the projected future image depicted on the sign began almost immediately to become manifest in the surrounding landscape. This in turn helped generate collective emotions of what people described to me as both happiness (okushemererwa) and hope or optimism (kwesiga). However, the later compensation payments generated a much more marked response, of course. Given that these payments represented simply extraordinary sums of money apparently just ‘dropping out of the sky’ – in an example of what the Comaroffs have called ‘millennial capitalism’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001) – they were generally received with a mixture of astonishment and excitement, and invariably resulted in much revelry. As one of my respondents later described it to me (in English): ‘On the day the electricity people came and gave us the money, I just couldn't believe it. I fell down, I couldn't talk, I couldn't talk. That night, we all danced our heads off!’ And she clapped her hands together for added emphasis. With both of these projects – and with various others that I have documented – at the point when the cash was handed over, all of the households who received compensation were also given a copy of the NRM's manifesto, or another piece of NRM political literature – documentation that always had a large photograph of President Museveni himself on the front, and (more importantly here) numerous glossy post-photographic images of planned development projects printed throughout their pages. This, in turn, had two effects. On the one hand, the cover image of Museveni appears to have generated a general association between the gifts and the president himself. Indeed, in my later interviews of twenty-seven recipients of the compensation payments, in response to my question ‘Where did this money come from?’, all of them replied, without a moment's hesitation: ‘From Museveni.’Footnote 11 On the other hand, and of greater relevance for my argument here, the documents’ numerous CGI and photoshop-driven images of fantastical future national development projects appear to have further amplified the effects of these compensation payments by giving a sense that they were just the beginning, with ‘much more to come’. In other words, the general impression seems to have been that if these two initial – and relatively modest – infrastructure projects had already delivered such great fortunes, then one could only imagine the scale of the future compensation payments that would attach to these later, and much grander, schemes.

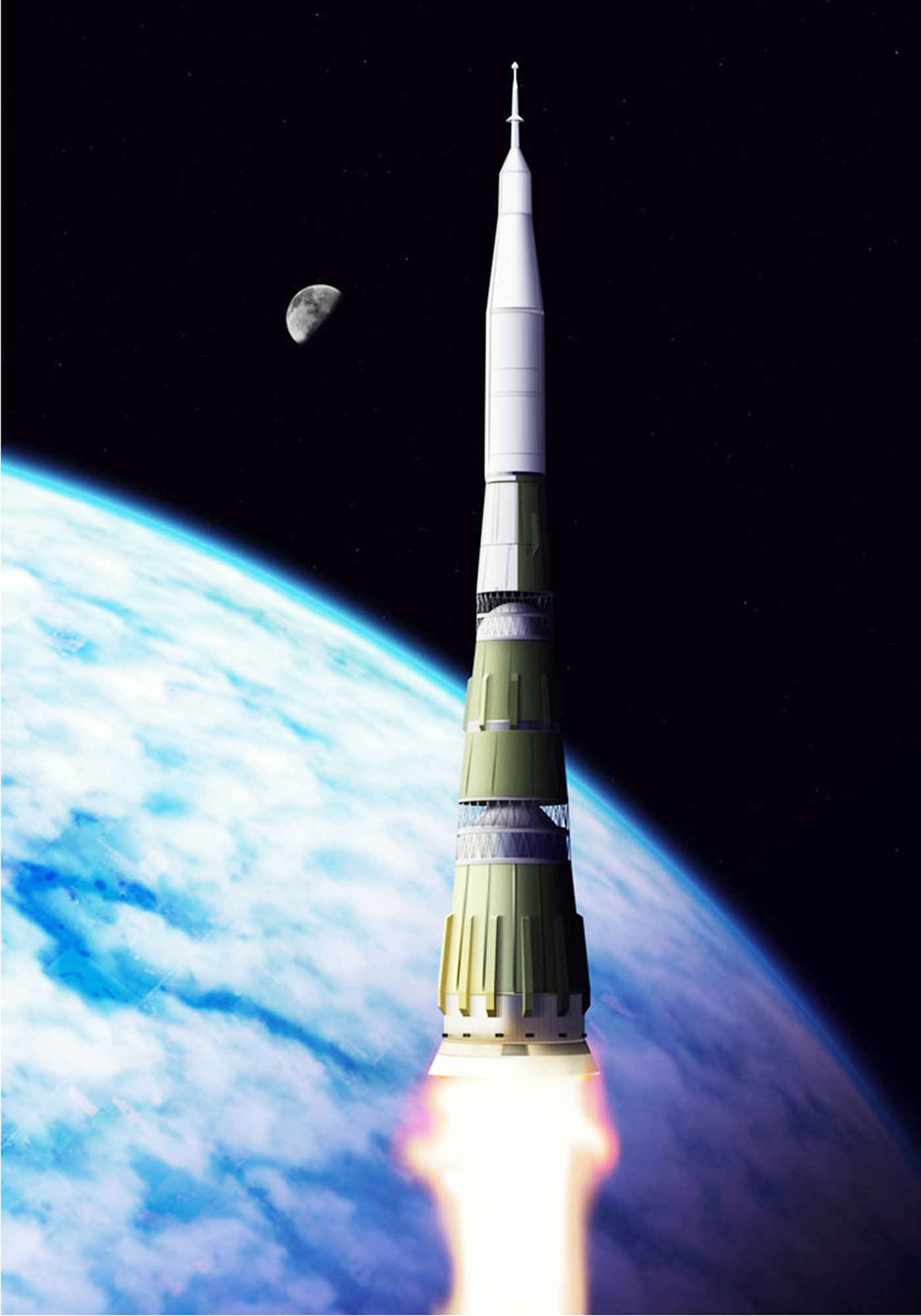

Once again, this logic produced a series of affective, embodied responses. Thus, by the time of my fieldwork in mid-2015, it had become common to see people sitting alone with these documents, in quiet contemplation, flicking through their pages to look at their images (in the manner of someone leafing through a consumer catalogue or a tourist brochure). On several occasions I observed people doing this, and noted how they might raise their eyebrows or shake their head in astonishment, or even gasp in awe, in response to some or other of the document's images. By mid-2015, it had also become usual for people to tear out these images from the documents and to stick them onto the walls of their living rooms (often alongside glossy government-sponsored newspaper inserts that carried the same sorts of pictures). Whereas it was once more usual for living rooms to be decorated with family photographs, random pages of newsprint, out-of-date political campaign posters or glossy posters of English Premier League football teams (Vokes Reference Vokes2010b), it is now just as likely that they will have become collages of fantastical futurism, constituted of glossy images of utopian education and training institutions, hi-tech agricultural schemes and industrial plants (including a car-making factory), and all sorts of public works projects (roads, bridges, airports, parks, government offices), to cite just a few of the examples I have recorded. One particular favourite among Rwampara's householders is a post-photographic image from the ‘Vision 2040’ document of a space rocket (which, in the document, illustrates Uganda's imagined future space programme; Figure 5).

Figure 5 Uganda is going to the moon!

Again, these wall-mounted images have become a site for embodied engagement, as people frequently stop to stare at them, often leaning in, pointing to certain features and touching them as they do so. However, it was in the context of the 2016 election campaigns that this physical engagement with these image objects became most marked. In the context of those campaigns – or at least during the NRM primary elections, which were taking place while I was in the field (Vokes Reference Vokes2016) – these wall-mounted images seemed to me to become particularly ‘active objects’ within political debate, as ardent government supporters might put their hands on them as they extolled the virtues of the NRM's achievements. On two occasions I witnessed, people started to bang them vigorously as they engaged in heated political debates, and – in another example of the instability of political affect – one opposition supporter began to tear down these pictures in another person's living room (before being physically restrained from doing so by those with whom he was arguing). My most lasting memory of people's engagement with these image objects relates to a focus group discussion that I was conducting as part of my broader research on the primaries. As the discussion turned to the NRM's record on development in the area, one young man stood up, marched across the room to the wall on which these images stood, placed both hands on the display, and explained to me in an excited way that Museveni had already achieved a lot here, but that there was all this to come, and that it would one day ‘make everybody rich!’

Conclusion

In recent years, African photographies, and visual cultures in general, have become digitalized, with often profound effects. There is little doubt that across the continent, and beyond, the main drivers of this process of digitalization have been smartphones and their associated technologies of social media and the internet – all of which have greatly altered the ways in which people produce, circulate and consume photographic images. Among their other effects, they have opened up what we might call particular kinds of ‘global image worlds’. However, it is also important to recognize that, over the past decade or so, Africa's digital image ‘revolution’ has involved not only smartphones and internet memes, but also other kinds of media and forms of digital imagery. In particular, recent years have seen the emergence across the continent of a new public political visual culture that began with billboards and subsequently spread to many other forms of media, and which is characterized by an extensive use of post-photographic techniques to present official visions of the future – visions that are increasingly influenced by fantasies of postcolonial modernity and late-capitalist development. In Uganda's case, there is nothing new about the state trying to use photography to represent its future visions, nor in its use of public visual artefacts as a means of generating an affective response to its development aspirations. Nevertheless, even in this context, there is something particularly potent about this new visual culture, with its ability to engender (or at least amplify) a sense of ‘fantastic possibilities’ that touches people within the most intimate arenas of their social lives. I would argue that there has been a subtle shift in President Museveni's own rhetoric in recent years, away from a focus on what his government has putatively already achieved, towards the ways in which he is going to lead Uganda into a bright new future.Footnote 12 In light of recent trends in the political science literature on the country, it is tempting to interpret this as just another example of the veteran Ugandan leader's increasing drift towards autocracy, and of his ongoing attempts to remain in power for life (see Vokes and Wilkins Reference Vokes and Wilkins2016). However, to read such rhetoric in only such instrumental terms would be to miss the ways in which Museveni's words also now play on the wonderful possibilities for the country's future that many Ugandans can now see – and feel – all around them.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the Annual Meeting of the African Studies Association (San Diego, November 2015), at the Pitt Rivers Museum (Oxford, May 2016) and at All Souls College (Oxford, May 2016). I would like to thank the audiences at all of these venues for their helpful comments. I would also like to thank Corinne Kratz, Katrien Pype, my wife Zheela Vokes, and two anonymous reviewers for the journal for their helpful suggestions. I would also like to thank Zheela for copyediting this article.