Introduction

Activation has become the de facto welfare strategy, where conditions for work are tied to receiving welfare. However, while the accumulating knowledge on activation has established the effectiveness of active labour market programmes (ALMPs) on employment and earnings, less is known on whether low-earning recipients gain financial independence. Many of today’s jobs do not pay life-sustaining wages, and former beneficiaries who work might return to welfare when they reach a point where they cannot go on without external help. In addition, less research has thrown light on what it takes to ‘activate’ more vulnerable welfare recipients. As McGann et al. (Reference McGann, Danneris and O’Sullivan2019) suggest, for ‘harder-to-employ’ recipients, supporting such clients requires alternative strategies and considerations than the standard train and place.

In this article, we answer the research question: what factors drive low-income families back to welfare? In particular, we discuss two important factors: debt accounts and young children. These two factors emerged from our survival analysis using longitudinal survey and administrative data of beneficiaries of a national Work Support Programme (WSP) in Singapore. That they trigger return to welfare after controlling for employment and earnings suggests the need to address them in activation policy. Yet it appears that research on activation has not sufficiently analysed these potential barriers to self-sufficiency.

The next section outlines what the activation literature has found, followed by a discussion of the literature assessing debt and young children in relation to activation. The section that follows then describes the Singapore policy context, focusing on the WSP and related policies. After this, the methodology of the study is described, and the findings are presented. A discussion explaining the findings and a conclusion with implications of the findings wrap up the article.

Activation, debt intervention and family policy

This section will summarize the key findings from the literature on ALMPs, followed by the literature on welfare return, before presenting the literature on the effects of debt and young children in the context of welfare programmes. Together, this review gives the backdrop of what we know about ALMPs thus far, and reveals the gaps in understanding the effects of debt and young children as factors to contend with.

In their meta-analysis, Card et al. (Reference Card, Kluve and Weber2018) found that ALMPs have been effective in improving employment and earnings. However, the effects vary by programme type and type of beneficiary. For disadvantaged workers, the group that our study is interested in, effect sizes were smaller than for the long-term unemployed, but larger than for general recipients of unemployment insurance (UI). Disadvantaged workers, who Card et al. defined as participants with low income or low labour market attachment, also benefitted more from job search assistance, whereas training and private sector employment subsidies had larger impacts on the long-term unemployed.

While the studies in the above meta-analysis looked at the impacts by programme and client types, some recent studies have begun considering the effects of case workers. These studies found positive effects of lower caseloads and higher intensity casework on employment (Van den Berg et al., Reference Van den Berg, Kjaersgaard and Rosholm2012; Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hofmann, Krug and Wolf2016; Maibom et al., Reference Maibom, Rosholm and Svarer2017; Ravn and Nielsen, Reference Ravn and Nielsen2019). They also found that employment outcomes were better when case workers had strong alliances with clients and were from the same social group (Behncke et al., Reference Behncke, Frölich and Lechner2010; Ravn and Bredgaard, Reference Ravn and Bredgaard2020), although one study also found better employment outcomes when case workers de-emphasized co-operative relationships (Behncke et al., Reference Behncke, Frölich and Lechner2007).

Overall, the evidence is clear that ALMPs have enabled participants to work and earn. However, the question remains whether the earnings are high enough to sustain financial independence. When low-income households become financially distressed, they might turn back to welfare. Yet, there have been few studies on welfare return since the flurry of articles published in the years after welfare reform in USA. Given that a main aim of welfare reform was to push people off welfare into employment, the main research interest then was whether people pushed off welfare stayed off welfare. The answer is probably to a limited extent. Return rates were estimated at between 20 to 36 per cent within three years (Born et al., Reference Born, Ovwigho and Cordero2002; Carrington et al., Reference Carrington, Mueser and Troske2002; Keng et al., Reference Keng, Garasky and Jensen2002; Loprest, Reference Loprest2002; Cheng, Reference Cheng2005). Kim (Reference Kim2010), which looked at a longer window of five years, found a return rate of 75 per cent.

The return rate appears to be lower outside of USA. Andrén and Gustafsson (Reference Andrén and Gustafsson2004: 67) found that in Sweden ‘half who exited return within a decade’, while van Berkel (Reference Van Berkel2007) estimated a return rate of 13 per cent within eighteen months in the Netherlands. However, this might be because of more generous UI in these other countries. Someone who becomes unemployed can turn to UI instead of social assistance unless they have poor job histories – for example, in the case of youths and immigrants (Bergmark and Bäckman, Reference Bergmark and Bäckman2004; van Berkel, Reference Van Berkel2007). The only study that had similar results to American studies is Ayala and Rodríguez (Reference Ayala and Rodríguez2010), where the long-term return rate was about 67 per cent in Madrid, Spain.

Some studies further assessed personal and programme factors of welfare return. In terms of personal characteristics, welfare recipients with low education (Loprest, Reference Loprest2002; Cheng, Reference Cheng2010), in economic insecurity (Keng, et al., Reference Keng, Garasky and Jensen2002; Kim, Reference Kim2010), who lack professional or craftsman skills (Cheng, Reference Cheng2010), who have limited work experience (Loprest, Reference Loprest2002), with poor physical and mental health (Loprest, Reference Loprest2002), and of minority ethnicity (Cheng, Reference Cheng2010) were more likely to return. Higher rates of return were also found among those who had a child or experienced job loss after exiting welfare, because many might have been in jobs that did not provide family leave or UI (Loprest, Reference Loprest2002). Finally, having young children and a longer lifetime history of welfare receipt increased the likelihood of return. However, having more children did not increase the likelihood of return (Born et al., Reference Born, Ovwigho and Cordero2002).

In terms of programme factors, Cheng (Reference Cheng2005) found that enrolment in Medicaid and food stamp programmes increased return to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which might suggest that, when in need, former beneficiaries turn to these in-kind programmes before returning to TANF. In addition, Loprest (Reference Loprest2002) found that receiving transitional services in the first three months after exiting welfare was important: families that made use of childcare services, health insurance and help with expenses were less likely to return.

All things considered, the research on ALMPs, while robust, is limited in explaining welfare dependency, especially when considering populations who might have high employment barriers and for which ALMPs might lead to poor jobs. As McGann et al. (Reference McGann, Danneris and O’Sullivan2019) suggest, for ‘harder-to-employ’ recipients, supporting such clients requires alternative strategies and considerations than the standard train and place. Dall and Danneris (Reference Dall and Danneris2019) further criticise the overemphasis of the activation literature on employment. It argues for the strengthening of research on spillover, unintended, and other effects not related to the labour market. It cited a few examples of studies which showed more nuanced effects of ALMPs such as unavailability of suitable employment, childcare and social support (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Thomson, Fenton and Gibson2016).

While our overall analysis included various possible predicates of welfare return, this article focuses on two factors which emerging research suggests might have important bearing on whether people return to welfare despite employment. The first factor is debt accumulation. Ng (Reference Ng2013) found that the top three reasons for application to the Work Support Programme – the government assistance programme that this article focuses on – are utilities arrears, mortgage or rent arrears, and other arrears. Unemployment was fourth. Thus, addressing arrears (debt that one is unable to pay) should arguably be an important component of ALMPs.

This position is supported by recent research suggesting that debt might have unique effects on cognitive and psychological function, independent of effects from poverty. What is intriguing is that several studies have found that it is the number of types of debts rather than debt amounts that significantly affects mental health or cognitive ability (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Bhugra, Bebbington, Brugha, Farrell, Coid, Fryers, Weich, Singleton and Meltzer2008; Meltzer et al., Reference Meltzer, Bebbington, Brugha, Farrell and Jenkins2013; Ong et al., Reference Ong, Theseira and Ng2019; Ng and Tan, Reference Ng and Tan2021). By extension, these cognitive and psychological effects could affect welfare dependence too.

Specifically, measuring the effects before and after a charity in Singapore provided debt relief to low-income households, Ong et al. (Reference Ong, Theseira and Ng2019: 7244) found that ‘having an additional debt account paid off improves cognitive functioning by about one quarter of a standard deviation (SD) and reduces the likelihood of exhibiting anxiety by 11 per cent and of present bias by 10 per cent’. The dollar value of debt relieved had a much smaller effect on cognitive function, and did not significantly change anxiety and present bias. The authors suggested that the results point to the effect of mental accounting rather than liquidity constraints. In essence, because people have mental categories of each type of debt, an additional debt ‘account’ leads to additional cognitive load and taxes the brain’s bandwidth. Such ‘debt account aversion’ was also found in another study where participants ‘consistently paid off small debts first’, although larger debts incurred higher interest rates (Amar et al., Reference Amar, Ariely, Ayal, Cryder and Rick2011). By extension, we might expect bandwidth tax from debt accounts to trigger welfare return too.

Yet, while there are some reports describing the inclusion of debt counselling or relief in ALMPs (e.g. Heidenreich and Aurich-Beerheide, Reference Heidenreich and Aurich-Beerheide2014; Sol, Reference Sol2016), there appears to be no study focused on the effects of debt or debt interventions in welfare or activation policy. Sol (Reference Sol2016) appears to be the most comprehensive in recording the extent that debt intervention is incorporated into activation. His survey of European countries found that the inclusion of debt intervention varies. Some, such as Cyprus and Italy, do not consider debt in their employment programmes. Others, such as Luxemburg and the Netherlands, offer debt relief facilities, but these are small and based on the volition of the job seeker. Still others, such as Belgium and Germany, integrate debt intervention as part of its employment services that also consider other potential barriers to employment. Given that struggling with debt is common among low-income households, and is a potential barrier to employment and self-reliance, we need more research to understand its effects.

A second factor that might need greater consideration in ALMP research is children. With more dual-earning families, and more women encouraged to participate in the labour force, family policy has changed from passive to active. From passively giving cash benefits in the past, today’s ‘activating family policy’ offers not only child benefits, but also childcare and parental leave (Ghysels and Van Lancker, Reference Ghysels and Van Lancker2011). These measures help parents, especially mothers, balance work and family obligations.

Thus, if care of children turns out to be a significant factor of welfare return, then ALMPs need to enhance supportive family services as part of activation. While work itself brings in income to feed the child, sustaining that work requires support from accessible and affordable childcare, and parental leave for parents to attend to exigencies without job or pay loss. Asserting that the ALMP literature has overlooked what activation means to the parent-worker, Kowalewska (Reference Kowalewska2017) found varied early child education and care (ECEC) practices among Western welfare states. On one extreme are countries such as Italy, Spain and USA, which Kowalewska classified as the general coercion model, featuring strict conditions but poor supports. On the other extreme are countries such as Belgium, Sweden and Finland, where childcare and leave supports are strong, but conditionalities ‘light’. In between are models such as the delayed coercion model in Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, and UK, where work exemptions are given to parents with young children.

Our study

The Singapore policy context

The focus of our study is a programme in Singapore that started as the Work Support Programme (WSP), and was expanded and renamed ComCare Short-to-Medium-Term Assistance (SMTA) in 2014. The SMTA is a national government assistance programme to individuals who are considered able to work, and includes work requirements similar to ALMPs in other countries. For example, one such requirement is meeting with a career officer to be placed in work or training. In addition, beneficiaries are referred to other assistance such as family, housing or work and training services as necessary. SMTA is means-tested with a household income eligibility criterion of below S$1,900 (US$1,405)Footnote 1 or S$650 (US$481) per capita. Applicants should also be looking for work or temporarily unable to work due to illness or caregiving of children, elderly or other dependants; or have little or no family support, savings or assets for daily needs (Ministry of Social and Family Development, 2017). By these criteria, WSP/SMTA assists beneficiaries who are unemployed as well as those who are employed but are in financial distress.

The study focused on a group of WSP/SMTA beneficiaries who can be considered among the lowest income of working households. Participants who were referred to our study were beneficiaries with children below the age of eighteen and who needed longer assistance, thus excluding from the study beneficiaries who only needed short employment assistance. When WSP first started, it also catered to a narrower group of the most needy households. SMTA has since expanded its eligibility criteria.

Debt management is included as part of WSP/SMTA. Case officers assess the extent of arrears, and work with beneficiaries on budgeting. They might liaise with creditors (such as the housing board and town councils) to restructure debt, and require that beneficiaries attend financial literacy workshops.

Childcare is also taken into account. Where a caregiver is asked to work, formal care arrangements for their young child(ren) are made. ECEC subsidies are higher for working mothers and negatively correlated with income (ECDA, 2019). More generally, public provision of leave in Singapore lies somewhere in the middle among industrialised economies. The Employment Act mandates a minimum of seven days of paid annual leave in the first year of employment, with an additional day thereafter. It also provides for other types of paid leave – for example, paid sick leave of at least fourteen days and paid maternity leave of sixteen weeks (Ministry of Manpower, 2019a). This is comparable to paid annual leave of at least twenty days, paid medical leave of at least two days, and paid parental leave of at least fourteen weeks in European countries (Ruhm, Reference Ruhm2011; Spasova et al., Reference Spasova, Bouget and Vanhercke2016; Eurofound, 2019). It is much higher than in USA, where legislation requires only twelve weeks of unpaid leave, for medical related purposes including: medical leave, care of newborn, and care of immediate family member with a health condition (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.).

The WSP/SMTA is also complemented by three other support measures. One is the Workfare Income Supplement (WIS), an earnings supplement for low wage workers. Another is the Progressive Wage Model (PWM), which, instead of a minimum wage, provides sector-specific progression pathways for workers to advance in their jobs and earn higher wages as they become more skilled, productive and take on higher job functions. Finally, the SkillsFuture movement and its accompanying programmes (to incentivise and subsidise lifelong learning, skills upgrading, and training to switch industries) aim to improve wages through education and training (SkillsFuture, 2019).

Overall, Singapore’s welfare context is one of a lean welfare system that emphasizes subsidizing social and human capital development over generous cash assistance (Ng, Reference Ng2015). Given its low unemployment rateFootnote 2 , its workfare system aims to assist low-income workers to retain their employment, to upskill, and to reduce their risk of unemployment – aside from compelling the unemployed to work. Further, its debt management and childcare supports are somewhere in the middle of ALMPs and family policies elsewhere. In light of public austerity yet rising economic hardship experienced by low-income households in many economies, Singapore’s lean welfare system and middle ground in terms of ALMPs and family policies offers a relevant case applicable to other welfare systems.

Data and period of study

Our dependent variable is return to the WSP/SMTA after exit from the WSP. This information is extracted from administrative data provided by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF). Our independent variables are from a longitudinal survey that the research team administered on WSP recipients from the time they entered WSP to three years after they exited. Most of the variables for this return analysis are taken from the third wave, which occurred one year after completion of the WSP, and gives the conditions of respondents closest to the time of return, if they did return. A few times, invariant characteristics were from the first wave when respondents started the WSP.

The period of analysis for return spans from 2010 (date of first exit from the WSP) to October 2017 (last date of entry from the administrative data). The explanatory variables from Wave Three spans from 2012-2014.

Survival analysis

We utilise the Kaplan-Meier survival function to report cumulative survival rates through time, and the Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate the relationship between our explanatory variables and expected odds to return.

The regression model is defined as follows:

Where

![]() ${t_i}$

is the duration to return to SMTA after graduation from WSP for an individual

${t_i}$

is the duration to return to SMTA after graduation from WSP for an individual

![]() $i$

,

$i$

,

![]() ${X_i}$

is a vector containing the values of the baseline variables for an individual

${X_i}$

is a vector containing the values of the baseline variables for an individual

![]() $i$

,

$i$

,

![]() $h\left( {{t_i}.{X_i}} \right)$

is the hazard generated by the value of

$h\left( {{t_i}.{X_i}} \right)$

is the hazard generated by the value of

![]() ${t_i}$

and

${t_i}$

and

![]() ${X_i}$

,

${X_i}$

,

![]() ${h_0}\left( {{t_i}} \right)$

is the baseline hazard function given

${h_0}\left( {{t_i}} \right)$

is the baseline hazard function given

![]() ${t_i}$

, and

${t_i}$

, and

![]() ${\rm{\beta }}$

is the vector of coefficients that the regression model estimates.

${\rm{\beta }}$

is the vector of coefficients that the regression model estimates.

Instead of reporting the raw estimated coefficients, we report the hazard ratios generated by these estimated coefficients. Computationally derived as the exponent of the coefficient estimate (

![]() ${\rm{exp}}\left( {\rm{\beta }} \right)$

), hazard ratios have the convenient interpretation as being the relative increase in risk generated by a marginal unit increase in the value of the variable.

${\rm{exp}}\left( {\rm{\beta }} \right)$

), hazard ratios have the convenient interpretation as being the relative increase in risk generated by a marginal unit increase in the value of the variable.

Variables

The following are the explanatory variables used in our analysis. First, we consider four economic variables as determinants of return. Monthly household income and employment status reflect the labour market performance of the respondents. The other two economic variables capture debt accumulation by the households, and include the total value of arrears owed and the number of types of arrears owed. Two separate debt variables enable the analysis of which matters more. The range of types of arrears includes mortgage, rental, utilities, conservancy charges, telecommunications, hire purchase instalments, medical etc.

Next, we also consider a total of eight sociodemographic characteristics. At the household level, we first include a dichotomous variable each for the presence of an infant aged zero to one, and a toddler aged above one to five. Next, we include the number of income earners and number of dependants, both variables excluding the individual himself or herself. At the level of the individual themselves, we look at education level (primary/elementary education and below=1), age, marital status (married=1), and gender (female=1).

Finally, we control for the following factors: (a) whether the respondent had ever experienced poverty in the past, which was self-reported in the first wave of data; (b) ethnicity; and (c) a dichotomous variable each for two interviewers who conducted many of the interviews, in order to remove any systematic biases from them.

Sample

The total sample size from Wave Three is 591, after dropping fifty cases because they had outlying values in arrears or family earnings, had died within the observation period, or were not the same respondent through the waves. Although small in size compared to other national studies, our sample represents less than 14 per cent attrition at each subsequent wave from 76 per cent of the WSP population in the first wave. Differences in baseline and programme characteristics between drop-outs and non-drop-outs were not statistically significant.

Limitations and robustness checks

While our survival analysis using Cox proportional hazards regression is more rigorous than simple linear or probabilistic regression, the reliability of the findings depends on assumptions within each model. For example, the assumption of proportionality required in the Cox model might not hold. For robustness checks, we also conducted parametric duration regressions in the family of multiplicative hazard models. In particular, we used the Exponential hazards model, the Weibull hazards model, and the Gompertz hazards model, and found that our estimated coefficients and their corresponding p-values are similar across all specifications.

Another limitation in our analysis is that, like other regression analyses, there could be omitted variables bias, and therefore our estimated effects might be over or under reported depending on the direction of correlation between our variables and the omitted unobserved characteristics. One set of unobserved variables include respondents’ personal characteristics such as personality, motivation or other family issues that are unavailable to the research. Still, the variables that our analysis focuses on represent the very concepts that we intend to measure, even if they absorb some of the effects of an unobserved characteristic.

We did extend the model to include other variables – namely, physical health, mental health, a child with poor grades, a child with health problems, and a difficult child, as employment barriers. The effects of the existing variables did not change with the addition of these variables, and these variables did not yield significant effects except for a difficult child.

Another set of omitted unobservables centres on selection into the programme, such that actual return depends not only on applicants’ backgrounds (the focus of the present study), but also institutional factors such as any eligibility or rejection criteria not apparent to the public or researchers, and case worker effects. For example, part of the results could be because welfare officers were more sympathetic to people with more debt accounts and younger children, and therefore more likely to approve applications with these presenting problems. Given the large and highly significant effects of debt accounts and presence of young children, this factor is likely to over-estimate but not negate our effects sizes.

The mechanisms posited in the discussion section could be tested if we had reliable data on expenses and cognitive ability. The latter was not collected, and reported expenses fluctuated greatly according to household income. This is unsurprising for our low-income sample of households, where expenses depended greatly on how much income one has, and where a majority of the households incurred arrears because expenses exceeded income from time to time. What we did do is explore various specifications of arrears, e.g., by types of arrears, besides the specification reported in this article. The possibility that a particular type of debt drives the results of debt accounts was ruled out.

Findings

Descriptive findings

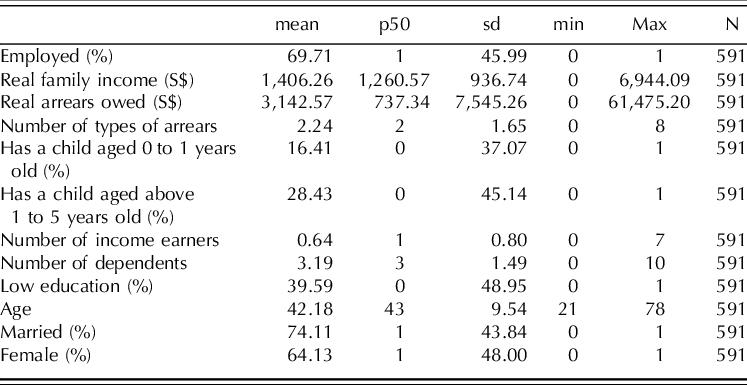

The participants in our study comprise a highly disadvantaged group, as shown in the socioeconomic conditions in Table 1. In terms of labour market performance, 69.71 per cent of our sample was employed and the mean monthly household income was S$1,406.26 (US$1,040). These levels are substantially lower than the national averages for employment and family income. Nationally, the citizen unemployment rate had averaged about 3 per cent from 2010-2014 (Ministry of Manpower, 2019b) and real median household earnings has been upwards of S$7,500 (US$5,547) since 2010. The mean real income level of households at about the fifth percentile was $1,738 (US$1,285) in 2013 (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2016).

Table 1 Summary statistics

Individuals in our sample also owed a substantial amount of arrears on average. The mean real total arrears amounted to $3,142.57 (US$2,324), which was 223.47 per cent of their household income on average. These arrears tended to originate from multiple sources, including housing-related necessities, such as rental and conservancy charges, and other non-housing related expenses, such as medical and telephone charges. On average, an individual who owed arrears had 2.24 types of arrears.

In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, 16.41 per cent of respondents had an infant child, and 28.43 per cent had a toddler aged above one to five. There were also few earners in our sampled households even though there were multiple dependants. Average households had 0.64 income earners and 3.19 dependants. As for individual characteristics, 39.59 per cent of the sample had a low education level of primary (elementary) school and below. Further, 74.11 per cent of the sample were married, and 64.13 per cent of the respondents are female.

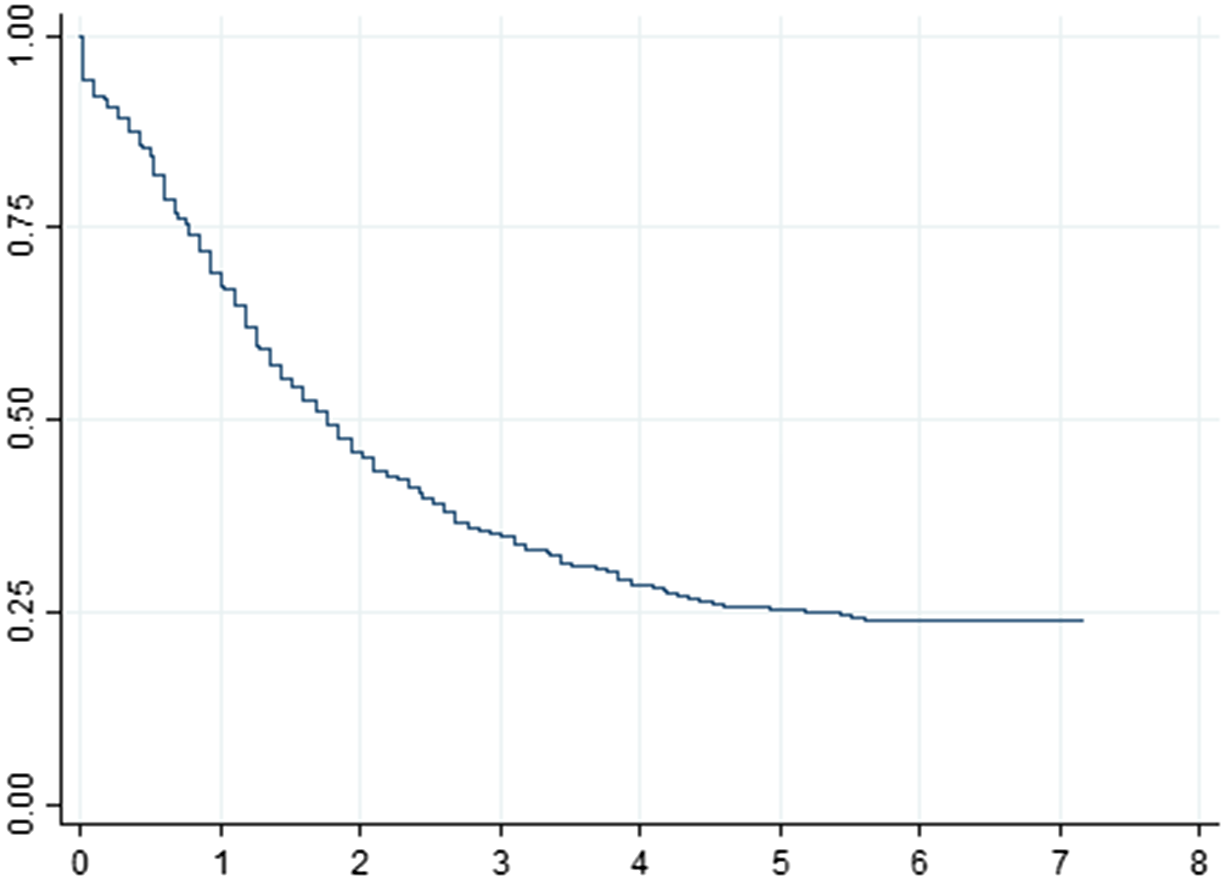

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival function of former WSP recipients – that is, the cumulative proportion of those who had not returned for assistance. Within a year of exit from WSP, 30.96 per cent of former WSP recipients had returned for SMTA, a rate similar to those found by other studies in the American context. By two years post-WSP, 54.15 per cent had returned and by Year 5, 75.80 per cent had returned for assistance. On average, among those who returned, mean duration to return was eighteen months and mean number of times they returned was 2.18.

Figure 1. Cumulative proportion of non-return to welfare over years.

The return rate is high, but judgement on whether it is too high needs to be made with the following considerations. First, the period of study is long. Second, this sample is at the bottom 5 per cent of households who are receiving assistance, and is therefore a highly disadvantaged group that might need repeated formal assistance. Third, some of the returnees might have received UI instead in other countries. Fourth, this return pattern to some extent reflects the goals of welfare policies in Singapore and the SMTA in particular. The Community Care Endowment Fund Annual Report 2016 states the aims of SMTA as such: ‘to develop and nurture responsible individuals and families; to assist clients who are work-capable but need assistance while they seek employment; and to assist those who are temporarily unable to work to tide over difficult periods’. Thus, the program, and the accompanying assistances, is designed to help people for a temporary period, after which beneficiaries are expected to take individual responsibility until a time when they need government assistance again.

Cox proportional hazards regression results

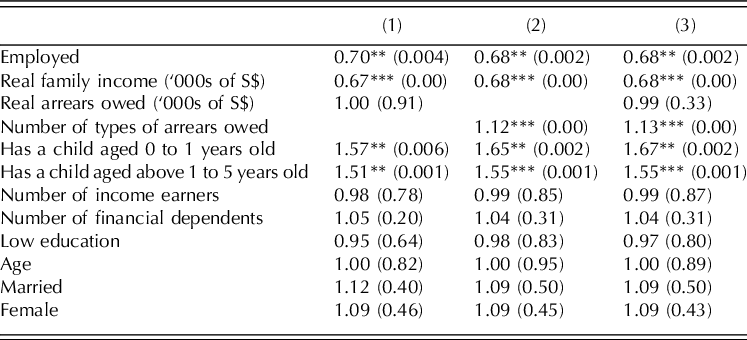

What factors push former recipients to return for assistance? The statistically significant results in the Cox regression suggest that return to SMTA was more likely if at one year after exit from WSP, respondents were unemployed, had lower household earnings, accumulated a higher number of arrears, and had an infant child or had a toddler child (Table 2). First, being employed decreases the expected odds of return by 32 per cent, a similar effect of earning S$1,000 (US$740) more. These two findings might be considered unsurprising or expected, but it is not a given that government policies meant to provide financial assistance are sensitive to real economic hardship. This finding suggests that SMTA is responsive to individuals’ economic situation, even if temporary.

Table 2 Cox regression hazard ratio of return to government assistance

Notes.

![]() $N = 591$

. P-values in parenthesis. Statistically significant at *.05, **.01, ***.001.

$N = 591$

. P-values in parenthesis. Statistically significant at *.05, **.01, ***.001.

Analysis controlled for prior experience of poverty, ethnicity and possible bias by two interviewers, who each conducted a significant share of the interviews.

Second, a common problem faced by low-income households is the inability to keep up with bills. In our sample, this triggers return to government assistance, but perhaps in a surprising manner. Table 2 evidences the contrasting effects of arrears amount and arrears types by including the two variables step-wise, with arrears amount only in Column 1, then number of types of arrears only in Column 2, and both variables in Column 3. While arrears amount yields no significant effect on welfare, an additional type of arrears owed increases the odds of return by 13 per centFootnote 3 . The finding that what matters is the number of debt accounts, rather than the dollar value of the debt, is a new finding in the welfare literature.

Third and finally, consistent with findings by Born et al. (Reference Born, Ovwigho and Cordero2002), the presence of young children in the household increases the likelihood of return, but not the number of children in the household. In our results, the presence of an infant increases the odds of return by 67 per cent and the presence of a toddler increases the odds of return by 55 per cent. These two effects are the largest by far among all the effects.

Discussion

Our study found that welfare return is related to unemployment, low household earnings, more types of arrears and presence of young children. Why might these factors matter, but not others, e.g., arrears values and number of children? The combination of significant variables suggests that beyond a simple explanation of insufficient earnings, how insufficient earnings result in welfare return might be through expense burdens and bandwidth tax. The latter has been evidenced and popularised by Mullainathan, Shafir and colleagues, that poverty impedes cognitive function because it taxes one’s mental bandwidth, leaving one’s brain with less resources for other tasks (Mani et al., Reference Mani, Mullainathan, Shafir and Zhao2013; Mullainathan and Shafir, Reference Mullainathan and Shafir2014). In the case of welfare return, bandwidth tax might exhaust respondent’s mental limit to continue coping on their own.

The mechanism is more straightforward for the first two significant variables: unemployment and low earnings. As household expenses still need to be met, the earnings shortfall drives one to look for alternative income sources, including returning to welfare. The earnings shortfall also consumes respondents’ mental bandwidth to keep on without formal assistance.

The mechanisms for debt accounts and presence of young children are less straightforward. For debt, what triggers welfare return is the number of types of arrears rather than the amount of arrears. This finding adds to the current evidence on the effects of debt accounts on mental health, cognitive function and decision making (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Bhugra, Bebbington, Brugha, Farrell, Coid, Fryers, Weich, Singleton and Meltzer2008; Meltzer et al., Reference Meltzer, Bebbington, Brugha, Farrell and Jenkins2013; Ong et al., Reference Ong, Theseira and Ng2019). The same mechanism appears to be at play in our findings, where the cognitive load and stress of accumulating debt accounts drive former recipients to turn back for government assistance. Furthermore, this effect is independent of employment and earnings, suggesting that the root cause of the debt effect through bandwidth tax is not unemployment or lack of income. Debt accounts itself triggers welfare return.

A similar mechanism might be at play in households with young children. On the expense front, expenditure in households with young children becomes elevated (Brandrup and Mance, Reference Brandrup and Mance2011), and this could explain why parents with young children are more likely to turn to welfare. For example, many social organisations in Singapore stock up milk powder and diapers because these baby essentials have become very expensive, and inability to afford them has triggered families to seek formal help (Charles, Reference Charles2017; Tay, Reference Tay2017). Compounding the effects of the higher expenses are greater vulnerability and dependence of young children, such that the worrying over basic necessities for a young child’s development is likely to impose additional mental burden on their parents.

Since the effects of young children on welfare return are independent of employment status and earnings level, parents of young children not being able to work and earn is not the reason why young children leads to welfare return in our findings. In fact, working might impose additional bandwidth tax on parents, who have to juggle childcare timings with work timings, childcare expenses, availability of childcare and parental leave for reasons such as a sick child or doctor’s visits (Morris and Coley, Reference Morris and Coley2004; Breitkreuz et al., Reference Breitkreuz, Williamson and Raine2010). Thus, if there are two mothers who are both employed and have the same earnings, the mother with a young child is more likely to return to welfare than the mother without a young child.

In summary, our findings converge on the explanation that bandwidth tax and expense burdens beyond one’s income ability could be the tipping point to welfare return. When the number of arrears pile up, and caring for young children becomes overwhelming, these tip low-income households to apply for welfare. Our finding adds to the literature on the effects of poverty and debt by showing a policy effect in terms of welfare return. It closes the loop that psychological and cognitive overload arising from poverty and debt accounts can lead to concrete consequences: in particular, welfare return.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to the current welfare policy literature by showing the importance of two factors on which ALMP with disadvantaged participants might need greater attention. First, our findings add to the nascent literature on the detrimental effects of debt, and of debt accounts rather than debt amounts. With our findings, we show a policy effect of debt accounts, besides psychological and cognitive effects.

One policy implication of this finding is that debt interventions should become more central in ALMPs, and implemented in ways that reduce cognitive load and bandwidth tax. Some may oppose debt intervention as part of government policy, seeing debt accumulation as due to personal fault. However, from our study as well as those of others (e.g., Bricker et al., Reference Bricker, Kennickell, Moore and Sabelhaus2012), we know that the debts incurred by low-income households are mainly in necessities such as housing, utilities, healthcare and telecommunications. They are due to low income that cannot keep up with expenses, something that ALMPs for disadvantaged participants must address.

Currently, debt restructuring and alleviation is under-explored in welfare work. Most debt interventions in ALMPs appear to be outsourced or follow mainly an education approach to help low-income families manage finances and debt better (Sol, Reference Sol2016). This is despite evidence that has shown the limited effectiveness of financial education (e.g., Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Lynch and Netemeyer2014). Thus, financial education should not be used as the default easy solution to preventing debt accumulation. Instead, policy attention on the nature and structure of debt faced by low-income households might go farther than financial education in enabling self-sufficiency and preventing welfare return. For example, employment offices could work with creditors to restructure the debt and bills in ways that reduce the overloading of mental bandwidth. Requirements that substantial debt reduction targets be achieved before graduating beneficiaries from ALMPs could also be set as key performance indicators (KPIs).

Second, our study also contributes to the developments in family policy research. Our finding that the presence of young children increases welfare return suggests the need to look at gaps in family-friendly work supports for low-income parents with young children. This involves addressing households’ ability to meet expenses such as diapers and milk powder. It also involves the intersections of maternity/paternity leave, affordable and accessible childcare, and hours of work relative to the hours of operations of childcare centres to enable work. The finding also suggests the importance of transition services, services that Loprest (Reference Loprest2002) also found prevented welfare return. For example, welfare case workers’ help to find accessible ECEC, apply for subsidies for the ECEC, and negotiate for jobs with matching hours could make a big difference.

Where low-income targets of ALMPs have limited access to parental leave and ECEC, social assistance with exemptions from work requirements might be necessary to prevent economic deprivation that compromises child well-being. Exemptions could still be important even if national provisions are in place, because workers from low-income families are often ineligible for them due to the higher prevalence of contract, daily-waged or informal jobs. Among the family policy models in Kowalewska (Reference Kowalewska2017), this would minimally require a delayed coercion model with work exemptions for parents with young children. The larger point is in rethinking the range of supportive policies to address the economic hardship of low-income households with young children.

Ultimately, our findings also point to the necessity of labour market interventions. At the root of our four significant factors of welfare return is the fact that these households do not earn family sustaining wages. Welfare does not address the labour market causes of why these families return for assistance, causes that relate to wage depression, leave policies and medical benefits. Thus, policies addressing these factors to ‘make work pay’ are vital. The findings also speak to the design of the next generation of ALMPs, which could focus on specific issues such as mental accounts and caregiving supports. The larger question is whether and how ALMPs continue to be relevant and effective for the most disadvantaged households.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daphne Lim, Joyce Lim, Lim Jia Liang, Joanna Tan and Arthur Soh for research assistance, and the Ministry of Social and Family Development for support and views. Any errors and opinions are however our own.