Introduction

Many commentators have highlighted the negative consequences of the introduction of indigenous languages to Kenyan media in the wake of pre- and post-independence political realities; however, the positive consequences far outweigh the negative ones. Africa is profoundly multilingual, with rich linguistic resources, yet many African countries have yet to overcome the negative effects of colonial language legacies and policies. Kenya is no exception. Following the colonial experience in Kenya and other African countries, the languages of Africa were subordinated to the languages of the colonial masters. Kenya was a British colony from 1920 to 1963; during this period, English gained status as the official language while the over fifty indigenous languages of Kenya became marginalized. Kenya gained its independence in 1963, and subsequent language policies recognized English as the official language while Kiswahili, a Bantu language spoken widely in African nations and largely considered a regional lingua franca, was declared the national language. To this end, the rest of the local languages in Kenya were not granted any special status, and they largely remained languages used for informal interactions within the home and in society. Fridah Kanana Erastus summarizes the role of indigenous languages in the continent by stating that “indigenous languages in Africa have been restricted to a few domains of use and the less formal ones such as intra-community communication, interpretational roles in local courts, use by politicians in local political rallies to name a few” (Reference Erastus2013:41). The Kenyan constitution of 2010 elevated Kiswahili to an official language; however, the language is yet to serve all the functionalities of English within the country.

One natural consequence is that English (as well as other languages of the colonial masters) has been assigned priority over indigenous languages, both in Kenya and elsewhere in Africa. English being considered more prestigious, its mastery has erroneously been used to judge speakers’ intellectual abilities or lack thereof. This situation extends to the media industry, with serious implications for mass communication and development. Erastus also notes that “the use of African languages in education was not always appreciated because the knowledge of a Western language always resulted in access to better jobs” (Reference Erastus2013:43). In South Africa, for example, similar attitudes contributed to resistance to the Bantu Education policy, which aimed at the introduction of African languages as a medium of instruction in schools (Roy-Campbell Reference Roy-Campbell, Arasanyin and Pemberton2006). In Kenya, some parents have, especially in recent years, made conscious choices not to teach their children their native languages, in order to give them a linguistic advantage, in the belief that mastery of English has more practical and strategic significance. This situation continues to grow, especially among middle- and upper-class families living in urban and semi-urban areas.

In this article, we look at the ramifications of this linguistic trajectory for communication in the mass media, with specific reference to the broadcast media in Kenya as a representative African country. In particular, we consider what happened when indigenous-language radio and television stations were introduced in the country due to specific pre- and post-independence realities, and the overall effect of this development on the polity. We first establish an overview of the language situation in Kenya and the actual position of the indigenous languages. The neglected potential of indigenous languages to serve as a catalyst for indigenous knowledge production and for polity development is the main focus here. Next, we trace the trajectory of mass media in Kenya and the developments that led to the introduction of indigenous languages to the media. We then consider the extant literature on the subject, highlighting views regarding the advantages and disadvantages of this linguistic development. As our contribution, we extract and crystallize these views, while offering our own perspectives on what we consider to be the main consequences of the development. Finally, we summarize these developments and offer conclusive thoughts regarding what we consider to be the solutions to some of the negative consequences highlighted in the literature.

The Language Trajectory in Kenya: Indigenous Languages vis-à-vis English

Language is a powerful tool for survival in any society, and some languages have more operational significance than others; thus, the elevation of English and Kiswahili over other languages, as highlighted in the introductory section above, has over the years locked out large sections of the populace from participating in national discourses relevant to their daily lives. Many individuals who have received low or sometimes no education can only express themselves in their native languages, and they therefore distance themselves from activities and processes that require any other language (Orao Reference Orao2009:78). This means that these people are excluded from public discourse and/or affairs that are conducted in languages other than their own. At the same time, they do not have access to any communication sent out in these other languages. This is despite the fact that African languages are more widely spoken than European ones throughout African countries, and some of them serve as cross-border languages in several African countries, such as Kiswahili in East Africa and Hausa in West Africa. Erastus observes that “development in Africa slows down because important communication relies on foreign languages and the parties involved in the process of development cannot interact effectively” (Reference Erastus2013:41). It is therefore a documented fact that access to relevant information is crucial to the economic, political, and social wellbeing of any society. The 1998/1999 World Development Report (World Bank 1999) notes that knowledge, not capital, is the key to sustainable economic and social development.

According to Zaline M. Roy-Campbell:

African languages are also vehicles for producing knowledge—for creating, encoding, sustaining and ultimately transmitting indigenous knowledge, the cultural knowledge and patterns of behavior of the society. Through lack of use of African languages in the educational domain, a wealth of indigenous knowledge is being locked away in these languages, and is gradually being lost as the custodians of this knowledge pass on. (Reference Roy-Campbell, Arasanyin and Pemberton2006:2)

Over the years, significant indigenous knowledge has been lost or eroded through formal education in many African countries, and in what Kwesi Prah calls “collective amnesia” (Reference Prah, Brock-Utne, Desai and Qorro2003).Footnote 1 The Europeans, in the process of translating and coining vocabulary and grammar in African languages, ended up using vocabulary that reflected their own settler and missionary ideologies (Makoni Reference Makoni and Prah1998). Consequently, they came up with words and expressions that talked about Africans without engaging them. “They sought to understand African cosmology on their own terms, and any conceptions that clashed with their own perceptions were marginalized and devalued.” (Roy-Campbell Reference Roy-Campbell, Arasanyin and Pemberton2006:3). One obvious consequence of this is that Africans were reduced to consumers rather than creators of knowledge. While addressing this issue, Prah points out that:

knowledge and education have to be constructed in the native languages of the people … new knowledge must build on the old and deal specifically with the material and social conditions in which the people live and eke out a livelihood. (Reference Prah1995:56)

Prah (Reference Prah, Brock-Utne, Desai and Qorro2003) opines that African realities should be brought to the fore through the continent’s rich languages, cultures, and history. This is the only way African countries can make meaningful contributions to the universal culture and body of knowledge (see also Mwaura Reference Mwaura2008).

The recent growth in the use of indigenous language in the mass media has not only provided an avenue for public participation and inclusiveness in national affairs for previously ignored populations, but it has also opened up new uses and expressional spaces for the indigenous languages in Kenya. The purpose of this article, therefore, is to examine these new interactional spaces and to document the positive and negative results of this development.

The Trajectory of Mass Media in Kenya

The state of Kenyan media has taken varying shapes over the years, from the inception of colonialism to the present. According to Tom Mshindi and Peter Mbeke (Reference Mshindi and Mbeke2008), the white settler-owned press was used solely as a vehicle for disseminating government information to the white settler communities. In 1930, the colonial government enacted a penal code which barred the publication of anti-colonial material and criminalized possession of the same as well as any form of defamation. This was driven by the fear that a free press would topple the government, as Kenyans united to push for independence (Makali Reference Makali2004). In 1952, the government banned all indigenous publications in response to the Mau Mau uprising and also intensified propaganda against nationalist movements through a declaration of emergency (Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011:8). The colonial government also controlled wireless and broadcasting—radio programs were controlled and censored and used as pro-colonial anti-nationalism propaganda tools (Mshindi & Mbeke Reference Mbeke2008). It became apparent in 1960 that Kenyan independence was inevitable, and the fear of the power of the mass media in the hands of an African government caused the colonialists to hurriedly form the Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) to take over broadcasting from the government-controlled system (Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011:8). The immediate consequence of this act was that KBC monopolized not only the radio sector but also television (Ogola Reference Ogola2011). Freedom of the press was therefore curtailed from the very beginning.

When Jomo Kenyatta, the first president of Kenya, came to power in 1964, he used state machinery, the police and the judiciary, to alienate those he considered political rivals. To achieve this, the media was targeted, manipulated, and sometimes threatened (Atieno-Odhiambo Reference Atieno-Odhiambo and Schatzberg1987). Immediately following independence, the media was heavily controlled and used for propaganda by the government. “The factors that shaped the development of media during the Kenyatta era were largely driven by the ideology of order, the push for development, political contention, and ideological issues surrounding media ownership” (Mbeke Reference Mbeke2008:8).

President Daniel Arap Moi succeeded Kenyatta in 1978 and went on to rule the country for twenty-four years in what was largely a dictatorial reign. During Moi’s presidency, the government restricted and limited political freedom, especially freedom of the press and freedom of expression and open criticism of the government. Any form of dissent toward the government was criminalized, and open reprisal toward critical media was intensified. Independent and critical publications were banned outright (Ogola Reference Ogola2011). The foreign press was not spared either – the government deported foreign correspondents and also ordered local media to stop publishing news by foreign wire services (Mshindi & Mbeke Reference Mbeke2008). However, agitation for political freedom from a single party rule to a multi-party state led to the introduction of multi-party politics in 1992. This tremendously improved the scope of political and press freedom. Moreover, there was also an increased flow of aid and improved donor conditions on the aid during the 1990s. The consequent economic liberalization led to the proliferation of independent newspapers and magazines, among them Economic Review and Finance (Mshindi & Mbeke Reference Mbeke2008). The ownership base of the media expanded, and the content covered also became bolder and more diversified. However, as Katharine Allen & Iginio Gagliardone note:

Many obstacles to media freedom remained, in particular, criminal libel laws and the Official Secrets Act. Also troubling was the Kenyan media’s proclivity to lobby on behalf of political parties, becoming a mouthpiece for government and rival parties rather than a purveyor of the Fourth Estate.Footnote 2 (Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011:9)

The politics of the day fully recognized the political power of the media and tried to maintain indirect control over it. President Moi bought controlling shares in The Standard Newspaper through proxies and used his business relationship with the principal shareholder to assert his influence over The Daily Nation (Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011). Media ownership continued to influence the content that was disseminated to the public.

In 2010, President Mwai Kibaki, who took over power from Moi, promulgated a new constitution that guaranteed more press freedoms. This entailed the “highest degree of independence and autonomy from state interference to date—at least in the arena of policy and citizens were granted the right of free access to public sector information” (Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011:10), leading to media exposure of government malpractices and activation of public discussions on political corruption and accountability. Later (in Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011), the government of Kenya, through the Digital Kenya Secretariat, initiated the analogue-to digital migration. This shift engendered positive development in the media industry in Kenya, leading to an increase in the number of radio stations, newspapers, and television stations. At the same time, the number of online platforms offering news expanded as a result of technological advancement and the availability of affordable internet. Digitization was expected to increase the number of platforms offering enriched local content, and also to increase the number of frequencies available to meet local demand (see Nyabuga & Booker Reference Nyabuga and Booker2013:87 for details).

However, there is one major shortcoming of the Kenyan media:

[its] moving towards monopoly, concentrating ownership in a few hands and producing duplicative and biased content. … Though Kenya has more than seven daily newspapers, 140 radio stations, 17 television stations and 13 weekly and monthly papers, the market is dominated by four groups (the Nation Media Group, the Standard Media Group, the Royal Media Group and Radio Africa). (Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011:13)

Furthermore, the mainstream media houses tend to stick to formal and official language in their broadcasts and talk shows, thereby alienating all those users who may feel constrained by this practice. Some of the main media outlets in Kenya will be spotlighted in this article, along with comments on their role in shaping the indigenous language media trajectory.

Theoretical Framework and Methodology

Discourse on community media has been approached largely from three perspectives: democratization and globalization, social responsibility, and multilingualism. The world over, community radio is seen as promoting public involvement in democratic processes and seeking to improve the livelihoods of those excluded from mainstream participation, especially women and children (UNESCO 2008). They do this by ensuring accountability by service providers, chiefly through partnering with civil society and other stakeholders to create awareness of public needs and pressuring the relevant government agencies to deliver (James Reference James2014). In a review of twenty-five empirical studies on radio in developing countries, Doreen Busolo and Jaime Manalo note that “community radio is developing communities through information dissemination, community participation/inclusion, and community access through programing” (Reference Busolo and Manalo2022:1). It is considered an important agent of promoting citizen participation in public affairs and sensitizing for timely interventions. It has been evidenced that beyond empowering communities, community radio can serve the socialization role of influencing behavior change and impacting positively on wider development outcomes (Da Costa Reference Da Costa2012). In this way, the masses also become part of the global economy, since globalized networking is enhanced through broadcast news, advertisement, and global entertainment.

Similarly, community radio is seen as it relates to social responsibility, which can in turn be viewed from two perspectives—the responsibility of the governing classes to the governed, and the responsibility of the owners and managers of the media establishments to complement and amplify this responsibility, and to refrain from employing the media for destructive or divisive politicking. This is more so because the use of indigenous languages on radio has often been criticized as a catalyst for tribal conflict. This situation places a huge burden of responsibility on the managers of the media, especially the radio stations. In this regard, Linje Manyozo (Reference Manyozo2009:1) notes that one aspect of social responsibility theory demands that “media organizations should operate with some level of concern for the public good.”

The multilingual dimension of this trajectory is also important. Kenya, like other African states, is a multilingual society, with so many languages “duelling” in different ways (Myers-Scotton Reference Myers-Scotton1993; Oloruntoba-Oju Reference Oloruntoba-Oju, Hurst-Harosh and Erastus2018, Reference Oloruntoba-Oju, Oloruntoba-Oju, van Pinxteren and Schmied2022).Footnote 3 The multilingual setting makes the imposition of a colonial language on entire ethnic populations problematic or conflict-prone in the first place, both from the point of view of communication and of identity and pride. Memory Mabika and Abiodun Salawu keenly observed that “the prevailing radio broadcasting landscape is limiting the use of minority languages in a multilingual nation” (Reference Mabika and Salawu2014:2391). This also links back to the issue of social responsibility, since “vernacular radio as a journalism practice presents unique implications for development and continued democratization, as well as for the media to fulfill its social responsibility” (Manyozo Reference Manyozo2009:1). Use of language in these radio stations is casual and relaxed and meant to enable maximum engagement with the listeners. Ghetto Radio online, for example, which is very popular with the youth, touts itself as “the voice of the streets” and broadcasts in “Lugha ya Mtaa” (Kiswahili for “street language” or “language of the hood”).

How does this theoretical trajectory as summarized above relate to the actual situation on the ground with the radio stations in Kenya? We turn our attention to this important question in the next section. Employing secondary research methodologies—relevant literature and secondary sources (media surveys and reports)—we examine the indigenous media trajectory in Kenya in line with the theoretical triad established above, namely, democratization and globalization, social responsibility, and multilingualism. We argue that the establishment of indigenous language radio stations is a mark of social responsibility in two distinct ways, and that the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages highlighted in the literature.

Notable Media Outlets and Their Role in Shaping the Indigenous Language Media Trajectory

Kenya has more than eleven radio corporations, which are owned and operated by various communities across the country. As indicated in the brief survey below, these are dispersed among numerous other radio stations that use the dominant colonial language.

State Run Kenyan Radio Stations

The Media Council of Kenya (2011) reports radio as the most popular and accessible medium of information dissemination. In the report, 95 percent of Kenyans are said to listen to the radio regularly as a source of news and information rather than entertainment. Most Kenyans listen to radio broadcasts through FM or AM stations. Other alternative methods include shortwave or mobile phone, which receive FM frequencies. With the shift to digital broadcast in Kenya and the increased affordability of the internet, more and more Kenyans also receive news through the internet and satellite radio. However, radio still remains the most popular source of news.

The first vernacular radio station, Kameme, was established in Kenya in 2000. Since then, the number of radio stations broadcasting in indigenous languages has risen to over thirty. In addition, “there is a large variety of commercial, state-run and community based local language stations on air” (Media Council of Kenya 2011:3). Community radio stations in this report are described as those that provide local, non-profit, participatory broadcasting with a development agenda. There are more than eleven community-owned radio stations, which are mostly funded by development agencies. They aim to provide rural communities with reliable news and information and also to create a space for public participation. They mostly serve the interest of the targeted community; they are community-driven, but there are concerns as to whether they are indeed community-owned (see Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011 for details). Radio is therefore the most competitive segment in the media industry, with various stations categorized as English, Swahili, and indigenous language, with further division into religious, sports, Sheng, and so on.

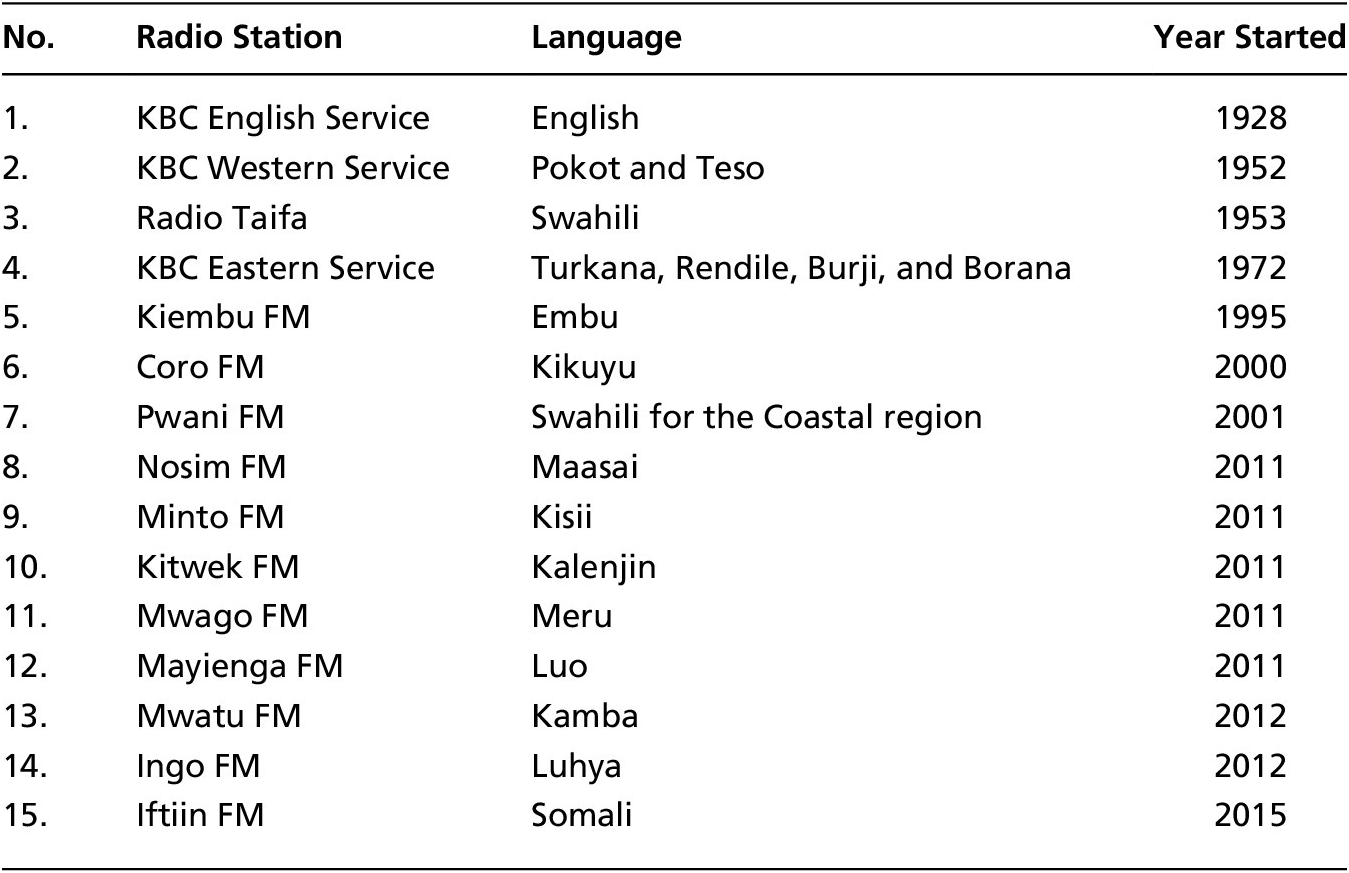

A more recent report, Kenya – Media Landscape Report by the BBC Media Action, indicates that the “radio sector is thriving—with over 100 radio stations many broadcasting in a variety of local languages” (BBC 2018:2). The report points out that many tribal language stations are very influential in rural areas where indigenous languages are spoken as the mother tongue. Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC), a government-owned parastatal entity established in 1928 when Kenya was still a British colony, runs the widest radio and television network in the country, with more than one hundred frequencies. It broadcasts in English and Swahili, as well as in select local languages of Kenya.Footnote 4 It owns seventeen regional radio stations, three commercial radio stations, and three television broadcast services (Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011:15). Radio Taifa, which is received throughout the nation, broadcasts in Swahili, while there is a national counterpart that broadcasts in English, the KBC English service. Table 1 presents a list of the state-run radio stations.

Table 1. State-run radio stations, their languages, and their chronology

(For more details see BBC 2018 and Allen & Gagliardone Reference Allen and Gagliardone2011)

A brief commentary on the key media stations in Table 1 will indicate that they try to operate in terms of the principles highlighted above, that is, democratization and globalization, social responsibility, and multilingualism. This display also enables us to see a glimpse of the range of indigenous languages that were left out of media coverage prior to the initiatives described above.

Royal Media Services (RMS)

Royal Media Services (RMS), one of the largest privately owned media houses in Kenya, also leads in the number of FM stations that broadcast in indigenous Kenyan languages. It owns thirteen radio stations and Citizen TV, which is one of the most popular television channels in Kenya. Out of the thirteen radio stations, eleven broadcast in indigenous languages (see Table 2). This makes the RMS the largest privately owned vernacular network in Kenya (BBC 2018).

Table 2. Privately run radio stations of the Royal Media Services (RMS)

The other two radio stations in the Royal Media stable are Radio Citizen, which broadcasts in Kiswahili and has a wide audience throughout the country, and Hot 96, which broadcasts in English with the youth and middle-aged listeners as the target.

Again, we see a glimpse of the indigenous radios covered by the social responsibility, democratization/globalization, and multilingualism path. Besides community radio, there are also other local, regional, and ethnically based radio stations that broadcast in indigenous Kenyan languages. The indigenous language stations are commercial enterprises whose broadcasts target a specific ethnic community in their own language for profit. They, too, have experienced growth, just like community radio. However, the indigenous language stations that broadcast in a regional ethnic language have been criticized for inciting ethnic hatred (especially during the post-election violence experienced in Kenya in 2007–2008), unlike the community radio stations, which called for calmness and peaceful co-existence. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights summarized the role of the indigenous language media in the post-election violence as follows: “The media, and particularly local language media, influenced or facilitated the influencing of communities to hate or to be violent against other communities” (Ngugi & Kinyua Reference Ngugi and Kinyua2014:10).

Kenyan Television

While radio remains the most popular and accessible form of media in Kenya, the Media Council of Kenya (2011:2) reports that television is also popular. Kenyans have had access to free television since the 1960s. However, in 2015 the government, through the Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology, directed all media channels to switch to digital broadcasting. Kenya was signatory to the ITU Geneva 2006 binding agreement and was expected to comply. To continue enjoying broadcasts, viewers were expected to switch to a television fitted with a digital tuner or a decoder connected to the existing analog television. Digital television offered more in terms of picture quality and signal reception.

The Kenyan television network has also grown in recent years, but at a much slower pace than the FM radio stations. The BBC Media Action report shows that in 2015, about 81 percent of Kenyans had access to television. In the 2018 survey, 67 percent of the urban respondents and 40 percent of rural respondents had access to television. There are more than twenty local television stations in Kenya. KBC, NTV, KTN, Citizen TV, and K24 are the biggest television stations in terms of coverage and viewership. The GeoPoll Media Measurement Service (Kenya Q3 2017 Radio & TV Audience Ratings Report) notes that Citizen TV has the highest number of viewers at 28 percent, followed by KTN at 14 percent, NTV at 11 percent, K24 at 6 percent, and KBC at 4 percent (BBC 2018). Their emphasis is on the dissemination of news and information. In recent years Kiss TV, a 24-hour music TV, and Classic TV, which airs African entertainment content, have pioneered entertainment-only local media. Besides these, there are international channels that, together with the local channels, make up the over fifty television channels available for Kenyan viewership and which the viewers depend on for news and information (Infoasaid 2010). Although the main television stations present their broadcasts and talk shows in both standard English and Kiswahili, it is not unusual to hear Sheng forms in their entertainment programs meant to appeal to young viewership. Again, digital migration has meant growth in television channels broadcasting in local languages. Examples of vernacular channels include Lake Victoria TV (LVTV) which broadcasts in Luo and Baite TV broadcasting in Meru and Swahili, among others.

The Programs

The programs on community and indigenous language radio stations cover the main broadcast divisions of news, programs, and entertainment. In his survey of the stations in Kenya, Enock Ochieng Mac’Ouma observes that the various programs cover thematic areas such as “education, business, investment, economy, family stewardship, news, spiritual nourishment, peace and security, politics and entertainment” (Reference Mac’Ouma2021:49). It should be noted that these programs are innocuous in themselves and cannot be tied exclusively to a specific (positive or negative) consequence. Every one of them has the potential to be used or misused one way or the other. It is presenters or listeners/callers on specific occasions who will determine the specific orientation of the message by their approach and their tone. In the next sections, we examine the positive and negative consequences that may potentially attach to the various programs.

Positive Consequences of Indigenous Language Stations in the Community

The introduction of indigenous language stations promoted values such as cultural preservation, information flow, increased development, and broad-based political participation (Manyozo Reference Manyozo2009). While these values may be threatened by some negative consequences, it is important to first highlight the positive ones.

Public Participation in Development

Effective communication is important in the mobilization of citizens to embrace the development agenda geared towards social, educational, economic, or even political change. Communication is not just mere transmission of information, but rather a process of creating and stimulating understanding as the basis for development (Waisbord Reference Waisbord, Gudykunst and Mody2001). Participatory development theorists recognize that it is exactly this lack of participation, inclusion of local knowledge, and sensitivity to cultural diversity and contexts which causes the failure of many development processes. This mobilization needs to be accomplished in a language that includes large sections of the populace in order to encourage nationalism, which is necessary for economic development (Batibo Reference Batibo2005).

In many African countries, large sections of the population are excluded from participating in democratic processes as the governments communicate information relevant to these processes in languages the populace is not competent in. This has been remedied in part by the emergence of indigenous language radio and television stations. Vernacular stations play an important role in reaching the masses while addressing issues that are important to the communities. Through the vernacular stations people speak out, and so there is the need to sensitize the people, through them, to be involved in development issues that arise in their communities. This idea resonates with the BBC Media report, which states:

Broadcasts in tribal languages may be more effective at targeting people of the same ethnic group in defined rural areas. Rural populations are generally less well educated than their urban counterparts and are less fluent in Kiswahili and English. Key messages also resonate more deeply when communicated in the audience’s mother tongue. (2018:9)

Indigenous radio stations usually capitalize on local news that the people in the immediate community can relate to, though they might also report a few news items of national or international significance. During call-in talk shows, listeners offer their opinions regarding development projects in their regions or their immediate needs, which ordinarily would not find expression on national platforms. Examples include replacing a bridge that has just been swept away, or low-level theft cases. They also comment on the viability or lack thereof of proposed projects at both community and national levels. Opinion polls conducted on call-in talk shows often allow listeners to vote on the priority levels of certain proposed development projects. As Ayo Bamgbose (Reference Bamgbose and Oloruntimehin2008) observes, democracy should go beyond the commonly held right of citizens to vote to elect, to include the right to question, influence, and evaluate their leaders and the policies they make.

Education and Sensitization

Access to information empowers citizens to participate in democratic processes that are relevant to them. It is therefore important that information regarding relevant issues be communicated in a language the citizens fully understand (Bamgbose Reference Bamgbose and Oloruntimehin2008). Because of high levels of illiteracy in Africa, there is a pressing need to use indigenous languages in order to reach large sections of the population. One of the most transformative activities of indigenous language television and radio stations is educating listeners on any number of important life topics. By inviting experts and specialists from different fields such as agriculture, markets and industry, citizen’s rights, justice processes, and matters of health, indigenous language stations are able to provide hitherto denied access to sometimes complex knowledge since it is broken down to listeners in their own tongues. Through regular programing, listeners are given the opportunity to interact with specialists and ask them questions on technical issues.

Sensitization of the public on popular action is also more effective through indigenous language television and radio stations, as has been evidenced in Kenya in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and HIV sensitization in the 1980s. Throughout the pandemic period, the government, through the Ministry of Health, held a daily press briefing to supply updates on the trends of the pandemic as well as to issue directives regarding expected public conduct. This was invariably done in English (and Kiswahili to a lesser degree). While both English and Kiswahili are official languages (Kiswahili doubles up as the national language), formal communications are offered mainly in English, with code-switches to Kiswahili for elaborations for the benefit of those who may be excluded by the use of English. Months into the pandemic there was a general complaint to the effect that the briefings were meant for the elite, otherwise they would not be made in English. Owing to the importance and the immediacy of the statements and directives in these briefs, the indigenous language stations played a significant role in taking up this information for translation and conveyance to the larger population. Earlier, this same role was evident in sensitization toward vaccination drives, voter registration initiatives, and even in urging citizens to turn out in large numbers to vote, to cite but a few examples.

Socialization and Social Cohesion

Socialization is the process through which members of a community are schooled into the norms and ideals of that society; they learn the values and norms of their society and how to peaceably live within it. Socialization makes people aware of the expectations of the group or society they live in (Arnett Reference Arnett1995). Owing to its strategic advantage of having a ready audience, the media has the potential to play a key role in socialization and the cultivation of worldview and values, such as political views, gender stereotypes, and body images (Genner & Suss Reference Genner and Suss2017). Indigenous language stations have upheld this role by including in their broadcasts programs aimed at inculcating certain social, religious, and political values and educating their audiences on community values—sociocultural, religious, and even political. By talking about common, everyday issues that all listeners can identify with, the stations promote social cohesion and integration (Maina Reference Maina2013). Invited experts extol certain behaviors and castigate others in line with their cultures. Regarding Simli radio, a listener says:

… it brings peace to the family. Most women who were misbehaving have changed from bad to good as result of listening to Simli Radio. The programme gives us advice and how to live a happy life together at home and in the community. As married men we have a responsibility and Simli Radio keeps telling us the adults, our roles. (Al-Hassan et al. Reference Al-hassan, Andani and Abdul-Malik2011:4)

A constant feature of programing in indigenous language radio is running commentaries on actual social events and happenings within and outside of the community and what these events portend for the future of the society as a whole. Indigenous language stations are popular mostly because they give dedicated attention to local issues that would never otherwise enjoy national coverage (Okoth Reference Okoth2015). The stations enjoy a more relaxed programing schedule because their audience is smaller, immediate, and more localized. Consequently, they are able to afford extended airtime to cover whole worship services, marriage or initiation ceremonies, or even a political rally, whereas the cost of only exceptional events can be afforded on national radio or television. This has a significant influence on the socialization aspect, which is further enhanced by making it possible to incorporate mundane community practices in the broadcast schedules, with times allotted for sending greetings, good mornings and goodnights, announcements of deaths and funeral dates, and occupational engagements (usually this has a cultural bearing, such as farming, fishing, and markets, besides white-collar jobs).

Virtual families and friendships have actually been created and nurtured through call-in interactions on such talk shows. Also, unlike on national radio and television, where guests invited to shows are most likely strangers, on indigenous language television and radio, the guests are often local figures who are probably frequently seen, or even known personally, by the listeners. Research indicates that we are more receptive to information when we feel bonded to the disseminator (Robb Reference Robb2009). Sometimes it is a simple thing such as interviewees who would otherwise never have met having the opportunity to interact in the studios of the indigenous stations that makes the stations so popular. The local stations have also promoted social cohesion through organizing sports fairs. Besides creatively occupying the youths, these fairs serve to unify communities, as there must be heightened interaction in the formation of teams, practice, and actual competitions.

Economic Empowerment and Livelihood Improvement

A World Development Report states that if it is put to good use, community media is very effective in promoting development in rural areas (World Bank 2001). As noted earlier, indigenous stations sensitize populations on issues of importance such as best agricultural practices, health matters, trading opportunities, climate matters, and contemporary social issues. Indigenous language radio stations have played an important role in promoting effective agricultural practices in Ghana (Chapman et al. Reference Chapman, Blench, Kranjac-Berisavljevic’ and Zakariah2003). Farmers are able to receive useful technical information presented in a language they understand. This is also true of the Kenyan indigenous language stations which broadcast shows that are meant to promote the mainstream economic activities of the localities of their target audiences. The previous failure to allow local media stations to operate for a long time denied Kenyans who cannot effectively interact in English or Kiswahili access to information that is crucial and helpful in the improvement of their livelihoods (Okoth Reference Okoth2015). In a 2019 Radio for Agriculture report based on five radio stations in Kenya, namely Rware FM (Nyeri), Syokimau FM (Kitui), Thĩĩrĩ FM (Meru County), Bus Radio (Kajiado), and Radio Jangwani (Marsabit), it is noted that Thĩĩrĩ FM ran a program which covered agriculture topics on macadamia and Irish potato production, dairy, and fish farming. Through a program called “Purgi Pith,” which literally means “farming and livestock rearing,” Ramogi FM, which broadcasts in Dholuo, educates listeners on how to apply modern farming methods in order to maximize production (Okoth Reference Okoth2015). This approach is replicated by other indigenous language radio stations as well.

The role of uplifting the livelihoods of listeners extends to include opportunities for entertainers and other creative artists who would have remained obscure on the national stage, especially artists who create and perform their music in indigenous languages. The national radio stations usually do not play their music, and when they do, they only use the music of artists who are already established in the industry, whose songs have already gained a level of popularity nationally. This gap has been bridged by indigenous language stations, which have created access even for beginners in the industry. One artist stated: “The vernacular radio stations in Dholuo have made work so easy; we simply present a CD to the presenters and with a few airplays, we get so many invites to perform where there is more revenue to make” (Okoth Reference Okoth2015).

Church choirs and other performance groups have also become more resourceful and innovative in their productions because they are assured of exposure for their music. This has in part been made possible by the Communications Authority of Kenya (CAK) Programming Code that, among other things, requires stations to dedicate 40 percent of their airtime to local content. Because the entertainment programs of Simli radio in Ghana, for example, are indigenous in design and broadcast, they are able to include modern forms of art that youths can identify with, to replace the traditional storytelling and community entertainments (Al-Hassan et al. Reference Al-hassan, Andani and Abdul-Malik2011).

Business advertising is also an important aspect of the role of indigenous language radio among communities. By offering advertising that is much more affordable than the prices on national radio, indigenous language stations create advertisement platforms even for single-shop retail outlets and service providers. Advertisements about boarding schools, colleges, and centers for boys’ initiation into manhood, which fill the airwaves from November to January, for example, provide the information required for immediate needs, as parents have to make time-bound choices guided by the fees and facilities advertised.

Margo Robb summarizes the role of community radio:

When radio fosters the participation of citizens and defends their interests, and makes good humour and hope its main purpose; when it truly informs; when it helps resolve the thousand and one problems of daily life; when all ideas are debated on its programs and all opinions respected; when cultural diversity is stimulated over commercial homogeneity; when women are main players in communication and not simply a pretty voice or a publicity gimmick; when no type of dictatorship is tolerated …; when everyone’s words fly without discrimination or censorship, that is community radio. (Reference Robb2009:114)

Development of Indigenous Languages

Scholars have proposed many ways to promote the indigenous languages of Africa. One way is by enshrining them in national policies and giving legal teeth to the policy (Bamgbose Reference Bamgbose and Bokamba2011); other ways include promoting a positive attitude by elevating the languages to official status and their use as languages of instruction within their immediate environments (Oloruntoba-Oju Reference Oloruntoba-Oju, Oloruntoba-Oju, van Pinxteren and Schmied2022; van Pinxteren Reference van Pinxteren, Oloruntoba-Oju, van Pinxteren and Schmied2022), production of creative works in indigenous languages (UNESCO 2001), and of course, use of indigenous languages in the media. However, the obvious positive consequence of the latter for the development of the languages themselves is often overlooked.

The use of indigenous African languages in the media not only counters the “cultural imperialism” represented by colonial languages but also promotes the learning and use of the indigenous languages. In empirical research, Ola Isola Ogunyemi found that the majority of listeners did not have any or sufficient competence in English to access media information in the language. In other words, the citizens were not getting “balanced information about the political and socio-economic situation in the country” (Reference Ogunyemi1995:8). On the other hand, some of the linguistic benefits of the indigenous language media include enhancing “competence in officialese” (Reference Ogunyemi1995:14). More recently, Methaetsile Leepile, former editor of a Botswanan newspaper, Mmegi, observed that, since “language encapsulates a people’s culture, social mores, values, and knowledge, more people can be brought into public and productive life by wider and more productive use of languages like Setswana” (Cultural Survival n.d.).

However, there are two main advantages afforded by the use of indigenous languages in the media. The first is that it expands the functionality of the languages beyond traditional (domestic and interpersonal) domains into the realm of literacy and mass communication. This means that the language is used, heard, and perceived more and more over a wider space and across a wider spectrum of participants. Second, it creates a trajectory of inductive learning of the language through vocabulary acquisition and pragmatic application by its users. In this case, the users learn more of the language by the sheer force of exposure to it due to its functioning within different domains. They simply pick up the nuances of the language without the intricacies of formal learning. Our argument here is that these advantages outweigh some of the negative consequences highlighted in the literature, which we discuss below.

Negative Consequences of Indigenous Language Radio Stations

There are a number of possible negative consequences or effects of the entry of local language media in the general media space in Kenya. These drawbacks fall under the general rubric of “misuse” of the media or the appropriation of the media to achieve inglorious ends.

Hateful Incitement

In the run-up to the Kenyan elections of 2007, the Kenyan media promoted civic education and encouraged the citizens to scrutinize the leaders they elected. However, following the breakout of violence in the wake of the contested election, the media is commonly held to have played a key role in misinforming and even inciting listeners to side with particular political divides. This was facilitated to a large degree by the indigenous language radio stations.

Howard (Reference Howard2009) documents incidents of incitement to violence by journalists who invited guests who spoke in a particular language and used coded language that was meant to be understood only by certain sections of the population. This situation was made worse by the polarization of the radio stations themselves along ethnic and political lines; they allowed themselves to be misused by politicians and influential people to broadcast incitements against their opponents. In 2011, one of the “Ocampo Six” (a popular name given to the six persons indicted at the International Criminal Court [ICC], having been accused of fanning 2007 post-election violence in Kenya), was Joshua Sang, a radio presenter with KASS FM, which broadcasts in Kalenjin. The station was seen to support William Ruto, then a member of the opposition and the running mate of the opposition presidential candidate. In their report on the 2007 post-election violence the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights said:

The media, and particularly local language media, influenced or facilitated the influencing of communities to hate or to be violent against other communities. Radio stations broadcasting in Kalenjin languages as well as in the Kikuyu language were culpable in this respect. Live phone-in programmes were particularly notorious for disseminating negative ethnic stereotypes, cultural chauvinism and the peddling of sheer untruths about the political situation or individual politicians. (KNCHR 2008)

The Commission of Inquiry on Post-Election Violence (CIPEV), also called the Waki Commission, further said:

Many recalled with horror, fear, and disgust the negative and inflammatory role of indigenous language radio stations in their testimony and statements to the Commission. In particular, they singled out KASS FM as having contributed to a climate of hate, negative ethnicity, and having incited violence in the Rift Valley. (CIPEV 2008:295)

Even in the absence of the heated tribal animosities that are heightened in every election period, indigenous language radio stations continue to activate tribal divisions by inviting popular community leaders to their talk shows. Many of these leaders have long been seen as opinion shapers in their communities, so the audience may find it difficult to reject their sometimes inflammatory messages. In recent years in Kenya, many politicians have been called out by the National Cohesion and Integration Commission over statements they have made on local radio and television stations.

Balkanization along Language Boundaries

While it has already been noted that indigenous language radio and television stations serve a major role in promoting social integration, the converse may sometimes be true, as the broadcasts tend to lock out citizens who cannot speak or understand messages in that language. In a multilingual country such as Kenya, which is already struggling with the problem of toxic ethnic rivalries, this may only serve to emphasize perceived boundaries and divisions, which are sometimes communicated in subtle and probably inadvertent ways in the station’s name, motto, or often-repeated slogans. Many of the radio stations run by the Royal Media Services are named in reflection of the common folk greeting of the broadcast area, Muuga (Meru), Chamgei (Kalenjin), Wimwaro (Embu), and Mulembe (Luyha). For example, the motto of Meru FM is “Meru FM, Ngwatanĩro ya Amĩĩru” (Meru FM, Unity of the Ameru), followed by a declaration of the physical boundaries of the said area, “Kuuma Ntonyĩrĩ mwanka Thũchi” (From Ntonyĩrĩ to Thũchi). Radio Ramogi, which targets Dholuo speakers, has “Kar Chuny Jaluo” (the desires of the luo) as its slogan, while Chamgei FM, with Kalenjin speakers as the target audience, uses the slogan “Chamgei FM, Muguleldab Kalenjin” (The heart of Kalenjin).

These often-repeated phrases inculcate ethnic loyalties and a sense of belonging. Although they may, to some extent, help to eliminate minority divisions within sub-tribes or even clans within the larger mother community (by urging the listeners to have a sense of belonging to a larger ethnic grouping), they might end up alienating other citizens who do not speak that particular indigenous language. This fear of balkanizing the country is one of the motivations for the refusal by post-independence Kenyan governments to allow indigenous radio stations to operate, given the stereotyped negative labeling of anything that is associated with a particular tribe. The government wanted to bring to an end any such perceptions (Okoth Reference Okoth2015).

Unhealthy Rivalries

Related to the above, the use of some indigenous languages rather than others also leads to unhealthy rivalries between the various ethnicities. This may generate non-cooperative or other negative attitudes on the part of some individuals or groups. This heterogeneity of languages and the inability of groups to agree is often cited as justification for continuing the use of colonial languages. “The trigger for warfare amongst the indigenous languages is the bureaucratic recognition of just a few of them for purposes of national integration and officialdom” (Oloruntoba-Oju Reference Oloruntoba-Oju, Oloruntoba-Oju, van Pinxteren and Schmied2022:106).

However, the answer to this criticism, and the related ones, is that language cannot be used in isolation or independently of other core causes to incite ethnic division or violence. The Hutu and Tutsi of Rwanda share “the same foods, the same songs and dances, and the same religions, in short, the same culture,” including language (Tirrell Reference Tirrell2015). Yet, the ruling Hutu government managed to incite the Hutu against the minority Tutsi, building on ancient tribal animosities. This means that speaking different languages is not reason enough to create divisions—language is just a tool that can be manipulated to incite divisions. Furthermore, censorship and effective regulation can be employed as a control mechanism to curb the balkanization effect (Aufderheide Reference Aufderheide1999). Equitable distribution of radio infrastructures, based on population and obvious viabilities, as well as social inclusion of alienated groups through satellite mini-stations, would take care of unhealthy rivalries.

Summary and Conclusion

The licensing of indigenous language radio and television stations in Kenya heralded a new dawn in the news and general communications sector, especially for semi-literate populations in the rural areas of Kenya. Prior to this development, these segments of the population were locked out of national news, communications, discourse, and development, as such announcements and discussions always took place in languages that they were not competent in. Indigenous language radio and television stations have bridged this gap by enabling citizens to be active participants in matters pertaining to their own development agenda. This has further been promoted by the ubiquitous and non-expensive mobile phones equipped with a radio application, which has made access to the radio broadcasts easier and more practical.

We have examined this indigenous language media trajectory in terms of its positive and negative consequences. Some of the positive consequences include public participation in development, education and sensitization, socialization and social cohesion, economic empowerment and livelihood improvement, and development of indigenous languages. On the other hand, disadvantages such as hateful incitement, balkanization along language boundaries, and unhealthy rivalries also occur. On the whole, much individual and community good has come out of these indigenous language radio and TV stations, and indications are that this is a growing sector of the economy with more benefits than the few negative outcomes that may arise.

We have analyzed the indigenous radio trajectory in Kenya through a theoretical triad of democratization/globalization, social responsibility, and multilingualism. It is clear that the situation in practice agrees with this triadic trajectory. Based on our examination of the situation, we conclude, most importantly, that the deployment of indigenous languages in media is a mark of social responsibility, and again that the advantages far outweigh the disadvantages. Each part of this conclusion is important. This is because social responsibility in media has often been seen more in terms of the media houses avoiding biased reporting and stemming inflammatory usage and ethnic jingoism on their respective fora. However, social responsibility is also reflected in the government’s policy decision to rescue indigenous languages from relegation in the first place, and then to deploy them usefully as a means of reaching the masses.

The twin advantage here bears repeating. First is the obvious advantage of conveying information to the farthest reaches of the country, especially the rural areas that had hitherto been cut off from the general information flow to the populace, due to a segregated use of language. An extension of this advantage is the tendency for the masses to become more involved in political and developmental programs. Second, however, and less discussed, is the advantage of developing the indigenous languages themselves. This also happens in two ways—first by expanding the functionality of the languages beyond traditional (domestic and interpersonal) domains, beyond the domain of strict, traditional orality and locality, to that of transmissive (technological) orality, media literacy, and globalization; and second by creating a trajectory of inductive learning of the language, through vocabulary acquisition and pragmatic application by its users. These advantages far outweigh the consideration of possible abuse of the indigenous language facility in the media. Measures can be put in place, as explained in the foregoing, to counter such abuses. More purposeful and proactive regulation and monitoring by the Media Council of Kenya, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission, and other regulatory bodies in the country, as well as responsible journalism and professionalism, would pre-empt many of the potentially negative outcomes of indigenous language radio and television. Furthermore, since even English or Swahili could be put to abusive use in the media, the solution is not to avoid or cancel out the indigenous languages and their proven advantages, but to find ways of stemming any tendency toward abusive usage through policy controls.