On June 12, 2016, the United States was confronted with another horrific gun massacre, this time at a nightclub in Orlando, Florida, resulting in the deaths of 49 people. Meanwhile, in Congress, efforts to advance gun control legislation had been long stymied by recalcitrant gun rights advocates with the backing of Republican leadership. On Wednesday, June 22, this standstill erupted in confrontation when Democratic members of Congress staged a nearly 26-hour sit-in on the floor of the House of Representatives, grinding proceedings to a halt, breaching formal rules, and demanding action on gun control bills before Congress entered the July 4 recess.

The sit-in occurred in response to recent failures by House Democrats to force the Republican majority to take up gun legislation and after several days of planning supported by Democratic House leadership. Shortly after the House convened that Wednesday morning, Georgia Congressman John Lewis, the civil rights icon chosen as the figurehead for the sit-in (figure 1), offered a floor speech pleading for gun control legislation. More than 40 colleagues joined him, many sitting on the floor of the well. Amid chants of “No bill, no break!” they proclaimed they would not budge until the majority leadership allowed consideration of gun control legislation (Bade, Caygle, and Weyl Reference Bade, Caygle and Weyl2016). As Politico noted, “What began as an intricate behind-the-scenes plot with a handful of members grew to include almost the entire 188-person Democratic Caucus” (Bade and Caygle Reference Bade and Caygle2016).

Figure 1 Representatives React after the Gun Control Sit-In

Representative John Lewis of Georgia braces Representative Jim Clyburn of South Carolina as he addresses supporters and press on the East front of the Capitol following the Democratic gun control sit-in on the House floor, June 23, 2016. Photo credit: Brian Alexander.

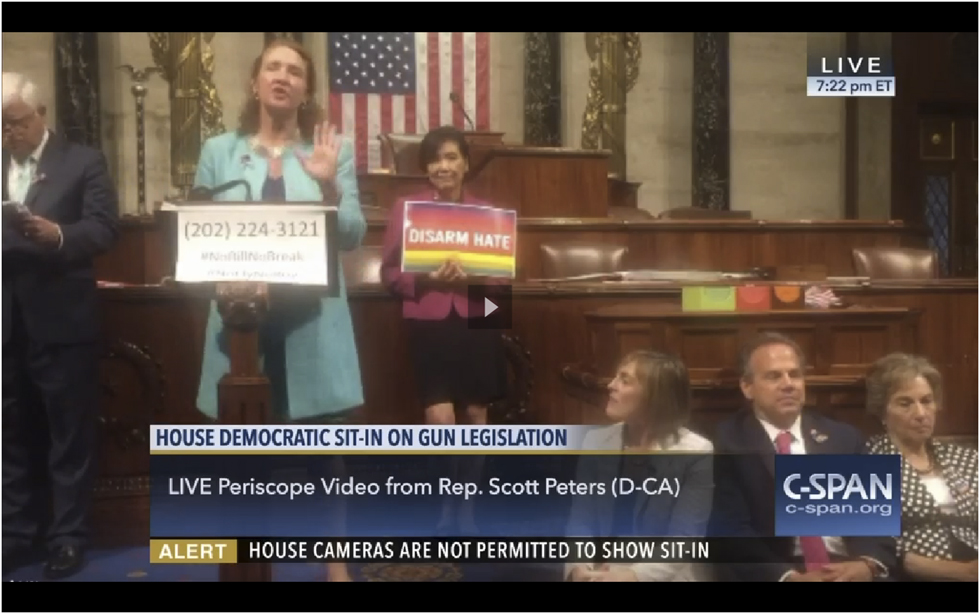

Republicans, who appeared caught off guard, quickly gaveled out and shut off House television cameras. The protest suspended almost all scheduled legislative business until 1 p.m. the next day and left Republican leadership with few options outside the extreme—and not chosen—act of using the Sergeant at Arms to forcibly restore order. In an even more extraordinary move, Democrats further violated House rules through the use of mobile phones to broadcast live video of the demonstration through social media. This streaming video was widely picked up by news outlets, shared on social media, and aired in its entirety by C-SPAN (Connors Reference Connors2016; figure 2).

Figure 2 The Democratic Sit-In on Gun Control, Broadcast Live by Members of Congress via Social Media and Carried by C-SPAN

Photo Credit: C-SPAN Screen Capture.

This protest was the most recent example of what I call “procedural disobedience”—when legislators willfully violate chamber rules and disrupt chamber business for a political purpose. Though acts of procedural disobedience can provide substantial benefits to participants and are rarely punished, they do not happen often. The infrequency of procedural disobedience is evidence for the enduring power of norms in how Congress operates. My argument, grounded in my observations as a congressional fellow, is that members often adhere to the rules out of respect for norms, rather than as a matter of a rational-choice calculation.

Republicans widely derided the sit-in. Many noted the unprecedented nature of such a breach of House rules and decorum. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan criticized the event as a “publicity stunt” and a “dangerous precedent” (McPherson Reference McPherson2017). Congressional observer David Hawkings called the sit-in one of the “truly memorable guerilla theater performances in the chamber of the House of Representatives” (Hawkings Reference Hawkings2016). Another long-serving Republican staff member offered this reaction, which aptly captured the outrage some observers felt: “There are rules, standards of conduct. Jesus Christ, they’re out there on cell phones, eating pizza, slouching all over the place. It’s like freakin’ Woodstock. It’s bullshit,” (personal interview with author, June 23, 2016). The formal response, however, was muted. No formal sanction was issued against the Democratic protestors and it was not until the opening of the 115th Congress that House rules were changed to deter such acts by imposing a financial penalty on members using recording devices within the chamber (Bordelon Reference Bordelon2017).

PROCEDURAL DISOBEDIENCE: THE POWER OF THE POWERLESS MINORITY

The 2016 gun sit-in suggests the potential for the tactics of civil disobedience as a source of minority power in the House of Representatives. The peaceful but disruptive tactic of the sit-in follows in the long tradition of civil disobedience, from Thoreau to Gandhi to the civil rights movement, the legacy of which was invoked with the selection of John Lewis as the symbolic leader of the demonstration (Helsel, Moe, and Russert Reference Helsel, Moe and Russert2016).

Procedural disobedience, in which members willfully violate formal chamber rules to assert influence over a majority that is unresponsive to their policy demands, is a distinct source of minority party power in the US House of Representatives.

Procedural disobedience, in which members willfully violate formal chamber rules to assert influence over a majority that is unresponsive to their policy demands, is a distinct source of minority party power in the US House of Representatives. Connelly and Pitney (Reference Connelly and Pitney1994), writing on minority party power at the end of the long period of Democratic control of the House, noted that Republicans frequently partnered with Democrats in their perennial minority status to advance their objectives. Gingrich’s ultimately successful stratagem of confrontation and “bombthrowing” (Connelly and Pitney Reference Connelly and Pitney1994) was unconventional by contemporary standards, but still within the rules of the institution. According to Green’s thorough analysis of minority party actions, refusal to leave the floor as an infrequently-used tactic (2015). However, common tactics of minority party power in the House remain consistent with the rules of the chamber to achieve goals that include electioneering, messaging, obstructing, and legislating.

The 2016 gun sit-in illustrates key aspects of procedural disobedience and its power: by willfully violating formal rules, a disruptive minority can convey its message to the public, rally its base, and at least temporarily obstruct the agenda of the majority including activity on unrelated legislative business. In addition, there was no formal punishment for this behavior: the majority’s immediate response, rather than sanctioning the protestors, was to suspend proceedings and gavel the chamber out of session. While the minority was not able to achieve its goal of votes on gun control legislation, it scored in these other ways.

Other cases show that, while rare, procedural disobedience is not unique to the Democratic sit-in of the 114th Congress and that it can be an effective tactic for political messaging and disrupting the majority agenda. Republicans, serving in the minority in the 110th Congress, staged a similar action in August 2008 with a rowdy takeover of the House chamber to oppose an offshore drilling ban (Bresnahan Reference Bresnahan2008). In contrast with the Democratic sit-in, however, the House had just gone into summer recess so formal business was not disrupted. Additionally, at that time, no social media platforms were available for Republicans to broadcast their protest live to the outside world. Formally there was little Democratic reprobation except to take extra steps the following August to restrict access to the House chamber during that summer’s recess (Pergram Reference Pergram2012). On the other hand, as CQ reported, “While the GOP spectacle didn’t bring the House back into session, it may have helped force Democrats to come up with legislation that would offer new offshore drilling” (Davenport Reference Davenport2008), even though the subsequent vote was largely symbolic. During the November 1995 partial government shutdown, minority Democrats occupied the chamber one Saturday while the House was in recess, carried posters, railed against then-Speaker Gingrich, and held the floor for several hours (US House of Representatives n.d.). This event was overshadowed by larger budget fights between House Republicans and the Clinton administration, and resulted in neither immediate legislative outcomes nor formal sanctions against Democratic protestors (Phillips Reference Phillips2016). Back in 1968, Republicans attempted to prevent a Democratic measure to force their presidential candidate, Richard Nixon, into televised debates by insisting on 33 quorum calls—an act that led then Democratic Speaker John McCormack to do “the opposite of what Ryan did [during the gun sit-in]—he used his authority under the rules to order the House chamber locked with the members inside until a compromise was struck” (Hawkings Reference Hawkings2016).

Unlike the Senate, where the minority has greater ability within the rules to disrupt proceedings—most notably the filibuster—the House offers its minority few options to halt the majority agenda. The few examples presented here suggest that procedural disobedience is an effective legislative tactic of the minority party of the House. With the possible exception of 1968, none of these instances of disruptive, rule-bending behavior were met with immediate formal consequences. Indeed, formal sanction for violations of decorum in the House is rare. For example, despite the “words taken down” process that allows a member to be penalized under Rule XVII for impugning the character of another, it is exceptionally uncommon for the Speaker to penalize a member being seated (Annenberg 2011; Alexander Reference Alexander2017). Even when Republican Congressman Joe Wilson of South Carolina shouted “You lie!” at President Obama during the 2009 State of the Union address, the formal rebuke to the surprising breach of decorum was only the softest penalty (Kane Reference Kane2009).

The politics of the gun debate may be unique in many ways. Despite this, the issue shares important traits with other issues that divide Republicans and Democrats, such as polarized public and legislator preferences, mobilization among partisan bases, and high issue salience (Pew Research Center 2014). Arguably, the strategic logic of congressional decision making supports such demonstrations when a weak minority party sees procedural, policy, and electoral benefits. The 2016 sit-in met all these conditions. The case of the gun sit-in, along with the other examples cited, suggests the power of a determined minority to upend standard legislative practice and score public relations victories—at least among its base (Gallup Reference Gallup2016)—on hotly contested polarized issues. In other words, in terms of achieving some narrowly defined objectives, procedural disobedience works.

DECORUM PREVAILS

The preceding evidence suggests that procedural disobedience is both effective and unlikely to be penalized. Moreover, Congress today is highly polarized. The intensity of ideological, strategic, and sometimes personal conflict between Republicans and Democrats is the greatest in recent history (Mann and Ornstein Reference Mann and Ornstein2008), while the minority party in the House is substantially disempowered (e.g., Binder Reference Binder2016). If procedural disobedience provides at least some political or strategic advantages, has historic precedent, and has a relatively minimal threat of sanction, it begs the question of why it is not used more often by a restive, weak minority on issues where polarization is highest.

If procedural disobedience provides at least some political or strategic advantages, has historic precedent, and has a relatively minimal threat of sanction, it begs the question of why it is not used more often by a restive, weak minority on issues where polarization is highest.

Why then do we not see it more often? On the one hand, strategically speaking, there are limited instances when a sufficient number of members would agree upon radically disruptive tactics. Such agreement occurs only where the minority party would find a combination of preference unity, mobilized constituencies, and high issue salience. Additionally, if the tactic were used more frequently, the likelihood of formal sanction by the majority would potentially increase—no more allowing the Democrats to “blow off steam,” as one interviewee described the Republican response to the gun sit-in (personal communication with the author, July 11, 2016). Moreover, it is plausible that public opinion could backfire against members who repeatedly do not allow the institution to function according to its own rules.

In addition to policy and strategic limitations surrounding the frequent use of procedural disobedience, there is evidence that part of the restraint stems from legislative norms pertaining to decorum. Despite all the antipathy toward Congress among its members—who run against it—and among their constituents who largely hold the institution in low regard (Roll Call Staff 2014), members of Congress continue to respect the rules of decorum and norms that formally and informally govern their conduct. As Matthews said in his seminal study of the Senate, there are “unwritten rules of the game, its norms of conduct, its approved manner behavior. Some things are just not done; others are met with widespread approval” (1960, 92). This also applies to the House.

The mechanism by which norms affect members of Congress in deciding to utilize procedural disobedience can be examined as both instrumental and non-instrumental. Much of the research on congressional norms is rooted in rational choice theories of Congress, in which norms act as constraints on strategic behavior. Norm adherence or rejection brings with it costs or benefits that a rational actor will weigh in determining whether to follow a norm. In this sense, norm adherence is instrumental based on what is strategically beneficial (Knight Reference Knight1992), a function of the capacity for sanctions (Sinclair Reference Sinclair1989), and because the expected payoff for doing so is greater than the benefits of not doing so (Weingast Reference Weingast1979). The expectation among members is that norm adherence will derive benefits to norm followers (Rohde, Ornstein, and Peabody Reference Rohde, Ornstein, Peabody and Parker1985). “These rules are enforced by sanctions, positive and negative, that affect status, project success, and other valued outcomes” (Azari and Smith Reference Azari and Smith2012, 40). In the instrumental sense, engaging in procedural disobedience will be based on a calculation of the likelihood of benefits and costs of being sanctioned for such action.

Beyond the strategic, cost-benefit component of norm adherence, it is possible that some aspect of the reluctance of members of the House minority to engage more frequently in procedural disobedience is simply because members respect the norms of the institution irrespective of purely instrumental or economic considerations. Norm adherence, in this sense, is rooted in a sense of what is appropriate—“fulfilling obligations in a role in a situation” (March and Olsen 1989, 160)—or what is agreed upon as proscribed or prescribed (Coleman Reference Coleman, Cook and Levi1990). For instance, adherence to the norm of courtesy, despite the unlikelihood of punishment for its violation, suggests non-instrumental norm adherence (Alexander Reference Alexander2017). Overby and Bell observe that “[as] norms become internalized over a long period they outlive the expiration of purely rational considerations and continue to exercise an influence on behavior even when individual utility concerns may dictate otherwise” (Overby and Bell Reference Overby and Bell2004, 921–922). Just as norms may constrain, they may guide behavior as well. Regarding minority party behavior, Green suggests, “[e]xisting norms and practices matter, too: some tactics gradually accrete until they develop a sort of ‘autonomous motivational dynamic,’ done simply because they always have been done and there is an unquestioned faith that they work” (Green Reference Green2015, 19).

While norms affect behavior, norms also change. Eric Uslaner’s (1993) classic study looked at the decline of comity in Congress during the 1980s and 1990s. Interviews on legislative norms I conducted with members and staff during my fellowship repeatedly spoke to an erosion of norms such as courtesy in favor of partisanship. One former member of Congress stated, “partisan patriotism has trumped institutional patriotism” (personal communication with author, July 11, 2016). A former senior staffer said, “norms to me are the manner in which people work with each other, especially across the aisle. And those norms have eroded terribly,” (personal communication with author, July 12, 2016). Another long-serving staff member suggested the number of members who want to “blow up the institution from the inside out” is growing (personal communication with author, August 8, 2016). If congressional norms are changing along these lines, support for procedural disobedience could increase.

Evidence presented here suggests that procedural disobedience is an effective tactic that goes relatively unpunished but is used only rarely. Further, it merits additional consideration if the reluctance to engage in procedural disobedience is driven by Congressional norms—whether because of strategic calculations of the costs of norm defection or the existence of norm adherence as a preference in its own right. If partisan conflict remains at an all-time high, informal norms may be what prevent procedural disobedience from more frequent use by a restive minority. Alternately, if norms are changing and the tactic is viewed as successful, we may have not seen our last sit-in.