Introduction

In The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Michael Pollan pinpointed corn’s significance: “There are some forty-five thousand items in the average American supermarket and more than a quarter of them now contain corn. This goes for the nonfood items as well—everything from the toothpaste and cosmetics to the disposable diapers, trash bags, cleaners, charcoal briquettes, matches, and batteries.”Footnote 1 Corn Products Refining (CPR) processed the corn to supply many such markets, yet CPR might not have succeeded. In 1906, President E. T. Bedford, board directors, and stockholders weighed divvying up profits between dividends and plant investments. Large dividends might deprive funds for factories. Outdated plants compromised efficiency and long-term profitability and might endanger workers. While Bedford fought some stockholders over plant upgrades, he (intentionally or not) tackled the problem of factory fires that resulted in explosions.Footnote 2

In years when Bedford piloted CPR, David J. Price, an engineer at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), itemized several bases for dust explosions: wood, wheat, corn, coal, sugar, powdered milk, cocoa powder, and spices, as well as dust in plants processing cotton, paper, fertilizers, and other items. Price explained how such items caused accidents: “The rapid passage or spreading of fire through a very finely divided dust cloud builds up considerable pressure and produces what we call a dust explosion.”Footnote 3

As researcher and safety campaigner, Price called out factory explosions: “28,000 industrial plants in the United States,” he wrote in 1936, “normally employing more than 1,325,000 persons, may have a dust explosion any moment if the conditions are favorable.” He continued: “During the last 19 years there have been at least 385 dust explosions in connection with the handling, milling, and processing of products largely of agricultural origin. As the result of these explosions 311 persons lost their lives and more than 693 workmen [workers] were injured.” Recently, Zhi Yuan, Nima Khakzad, Faisal Khan, and Paul Amyotte collected data from 1785 to 2012 to show that the United States accounted for 1,611 out of 2,870 dust explosions across the globe.Footnote 4

Overall, workplace accidents swelled around 1900, but some categories receded by or before 1930. In Safety First, Mark Aldrich called attention to this pattern and tied accidents at the century’s start to such problems as the speed and features of machines, congested factory space, and the inadequate legal options predating workmen’s compensation laws (now called workers’ compensation).Footnote 5 Then, from 1913 to 1922, according to Aldrich, looking at United States Steel, injuries fell from 60.3 to 13.0 “per million manhours.” Du Pont registered a similar downward (safer) pattern.Footnote 6 Focusing on factory fires that prompted explosions, Price detected “a marked reduction in losses from dust explosions … during the five-year period from 1930 to 1934.” Yuan and coauthors identified complicating factors with data from country to country, yet seemed to show that U.S. rates fell around 1930, and further after about 1960. From a historical perspective, why did U.S. explosions begin to retreat roughly by 1930?Footnote 7

To understand factory fires that triggered explosions, I assess the proposition that safety rested in part on corporate governance. Reforms like workmen’s compensation laws pressed CPR and other firms to mitigate explosions.Footnote 8 In addition, varied governance regimes were key to producing results. At Du Pont, family managers—especially Pierre S. du Pont—held a tight grip on the firm’s governance and supported safety. At U.S. Steel, Judge Elbert H. Gary, by working closely with J. P. Morgan, could favor safety if it suited his purposes.Footnote 9 CPR illustrated a third governance structure—one in which owners clashed over allocating profits for dividends or investments.

The proposition that safety depended to a degree on corporate governance leads me—writing as a historian—to engage the historiography of capitalism. One strand finds CPR’s leaders were not alone in their disputes. From the Progressive Era to the present day, historians have pointed to conflict among owners at mergers. To be sure, at some combinations like Du Pont, an interest held majority stock and mostly avoided conflict. At other amalgamations in which ownership was fractured, stockholders disagreed over topics such as control, a company’s future, management, and dividends.Footnote 10 Scholars also have exposed and explored combinations’ injustices. Aside from a long-standing interest in mergers’ power, including anticompetitive activities and antitrust prosecutions, historians have pursued other major topics, including workers’ rights and environmental harms. Can the two strands be connected? Can owner disputes be tied to social ills? A promising case is CPR.Footnote 11

Its story begins with the “merger movement,” dating to five years on either side of 1900; and like several consolidations, CPR and its predecessor, Corn Products (1902–1906), stumbled at first.Footnote 12 In 1906, Corn Products almost failed; in 1913, CPR landed an antitrust suit. Even then, as scholars Arthur Dewing and Brian Peckham indicated, owners at the corn mergers differed over dividends. In 1914, Dewing commended Bedford but raised concerns that at Corn Products, large dividends jeopardized the merger’s survival. Writing about CPR in 1983, Peckham’s remarks supported Bedford, who testified in 1916 that his executive committee agreed: “We would rehabilitate the plants, extend the markets, and look for what prosperity we could get from an increased consumption.” Bedford’s statement gained traction insofar as he put off dividends, a point Peckham noted.Footnote 13 Because Dewing published his book before dividends and antitrust were fully settled, and Peckham cited dividends but focused primarily on CPR’s antitrust case, it has remained for future analysis how the tradeoff between dividends and investments affected safety.

To gauge dividends’ significance, consider the board of director’s job in setting payments as a fraction of profits. In 1906–1907, dividends absorbed 84 percent of CPR’s total income, according to the Commercial and Financial Chronicle, whereas in succeeding years, the board weighed large and moderate payments. In 1913, for instance, directors should have declared dividends of 7 percent (consuming 57 percent of total net income) but paid 5 percent (amounting to 41 percent). Smaller dividends might release sums vital for investments.Footnote 14

CPR began precariously because dividends vied with plant improvements but also investments for safety. As its engineers upgraded factories, they attempted to avert or blunt explosions. Citing other types of engineering advances, Aldrich wrote: “These examples supported the longstanding creed of the safety engineer that injuries were a symptom of inefficiency.” John Fabian Witt made a similar point, finding engineers interpreted injuries at the time as “waste.” CPR engineers may have applied these ideas about accidents to the problem of explosions. When they addressed costs, my reading suggests CPR engineers worked to curtail lives lost and injured in fires that too often resulted in explosions.Footnote 15 Could owners finance factory improvements? Although Bedford tried various strategies, success turned on challenges over dividends, as well as governance.

Initial Disputes at Corn Products

Bedford’s predicament in 1906 takes us back to Corn Products in 1902. Between 1902 and 1906, Corn Products nearly succumbed to a fight among owners and rivals. The issue entailed the fate of an employee, but dividends and degraded plants inflamed disputes.Footnote 16 The New York Glucose Company (NYGC), Corn Products’ most irritating competitor, was backed by Standard Oil people, including E. T. Bedford, who until 1911 divided his time between Standard and the corn refiners—initially NYGC.Footnote 17 Opposing Bedford, at Corn Products, C. H. Matthiessen served as president. In 1897, the family’s thriving Chicago business merged into the Glucose Sugar Refining Company (GSRC), which in 1902 joined the Corn Products combination. Dewing and Fortune praised Bedford, more so than those in charge of Corn Products. Given incomplete information, critics might be right; alternatively, Matthiessen might have braved a difficult situation. Because he did not hold complete authority over the individual firms making up Corn Products, he may have had less control over Corn Products than Bedford had over NYGC.Footnote 18

A dispute over an engineer’s job launched a power struggle between the president of American Glucose—a firm Glucose Sugar absorbed—and new leadership at GSRC. Dewing and Fortune made this clear.Footnote 19 When the employee was eliminated, complaints reached Standard Oil, where parties from American Glucose and Standard created NYGC.Footnote 20 The GSRC engineer became a director on NYGC’s board and, as the New York Times reported, “engaged as manager for the plant.”Footnote 21 Testifying in the antitrust case, J. B. Reichmann, who had worked for a prior merger, called NYGC “the best plant at that time [1902–1906].”Footnote 22 With assets of over $6 million and initial debt of $2.5 million, the firm earned profits of $0.49 million in its eight months of 1902, $0.87 million in 1903, $0.80 million in 1904, and $0.62 million in 1905.Footnote 23

In 1902, Matthiessen made a play for NYGC, but “was able to acquire,” Dewing related, “exactly 49% of the issued stock.”Footnote 24 Standard brass created a voting trust to closely manage the 51 percent of remaining shares. At least eight owners, being Standard Oil directors or high-ranking managers, effectively controlled NYGC. Peckham stressed family reasons for Bedford’s involvement in NYGC—a point Dewing and Fortune also cited. Reading Dewing, Fortune, and antitrust records, I find that family reasons, though certainly valid, did not preclude owner disputes as a cause of the ensuing battle.Footnote 25 Thus, through external competition and internal denial of dividends, NYGC attacked Corn Products—a firm made vulnerable by its deteriorating plants.Footnote 26

The Attack

Frederick T. Fisher, who testified in the antitrust case on accounting matters, explained how NYGC’s assault unfolded. Whereas in 1904 Bedford’s board declared a dividend, in 1905 earnings continued but dividends ceased. Pressed, Fisher answered these questions.

Q. Well, they were waging war against each other?

A. Competition was very keen, yes, sir.

Q. Well, there was a trade war on, was there not?

A. Yes, there was a trade war.

The government’s attorney turned to dividends:

Q. And you did not want to give Matthiessen [Corn Products] any dividends … to help him carry on that war?

A. It would not have been wise to declare any dividends.

Fisher added:

The New York Glucose Company only had cash of about $300,000, at that time, and it was shown that at all times the New York Glucose Company required over a million dollars working capital.

This point did not preclude NYGC denying dividends to starve Corn Products of cash.Footnote 27

Corn Products’ leaders might have staved off NYGC’s hostile actions. In its first year, the firm performed well enough—profits topped $4 million. However, profits fell the next year (1903–1904) to $1.49 million, rebounded slightly in 1904–1905 to $1.69 million, but slumped in 1905–1906 to $0.38 million ($150,278 into August). Dewing stressed inefficiency, competition, falling profits, and large dividends. Dividends competed with profits: $1.43 million in dividends the first year, but then $3.73 million in 1903–1904, and $1.92 million in 1904–1905. For a merger with assets ten times larger than NYGC at roughly $74 million, and debts initially at about $10 million, its performance might have been better. Looking back in 1913, an accounting firm contended that “had the Company appropriated as much for depreciation and repairs during the years ending February 28th 1905 and 1906 as was done in the first year under review [1903–1904] it is apparent that there would have been a deficit during each of the two latter years.” Dewing, the auditors, and other materials suggested that different interests failed to prevent factories from deteriorating.Footnote 28

Among outdated plants, National Starch (1900) entered the merger of Corn Products and stood out, as Dewing put it, for being upstaged by “newer independent mills.”Footnote 29 As early as March 1902, William F. Piel Jr. categorized as “inactive” eleven out of roughly twenty-one starch properties. In October 1904, then secretary of National Starch J. B. Reichmann identified four active plants, but their value was debatable. Peckham summarized problems at National Starch—thus adding force to concerns by Dewing, Piel, and Reichmann.Footnote 30

Another major problem took shape at the Chicago plant. NYGC’s denial of dividends, plus the faulty starch plants and other factors, may have prevented Corn Products’ leadership from adequately maintaining this facility. At the antitrust trial in 1916, George Moffett, CPR’s top manufacturing official, recounted the plant’s 1906 status when Corn Products nearly failed: “The Chicago plant was settling every day,” hampering the factory’s operation. “You could not repair it. The building was so enormously heavy that when … an oak column, for instance, would snap off down on the first or second floors, as they were doing all the time, when you put in a new one you put in a shorter one than was originally there, because it was impossible to jack the building up to the original floor levels.” He elaborated: “Here was a building that was twelve or thirteen stories high and loaded with heavy machinery … and each one of those columns carrying probably 300 or 400 tons of load.” Finding that “the building was twisting as well as the floors sinking and the walls bulging,” Moffett warned: “If it [the Chicago plant] had fallen down, it would have killed most of them [the 700 workers] that is what we were worried about.” Higher-ups shared his assessment and soon halted work.Footnote 31

Prior to 1906, inefficient conditions were apparent at other key plants. It was possible for some plants to be rated “safe” and yet be inefficient. Consider Davenport, Iowa. J. J. Merrill, a plant manager, testified for Davenport.: “It was not an efficient plant, on account of the old type of machinery and the poor arrangement.” For Waukegan, Illinois, he singled out the “mill construction,” and explained: “Some of them [the mills] simply [were] the joist construction; the walls were brick and the posts and girders were wood. The nature of our process is such that our work is particularly hard on buildings, the construction of which has any wood in it.” Merrill implied the building shook. Concerning its inefficiency, he noted: “The arrangement of the plant was such that a greater number of men were required to operate it than are required to-day to operate a modern plant.” “At the Pekin plant,” in Illinois, Merrill stated: “The arrangement of the apparatus was particularly bad from an efficient standpoint,” especially in terms of energy usage. As for some instances of wood, F. L. Jeffries, superintendent of a facility in Granite City, Illinois, answered: “The [Granite City plant’s] wooden construction had become rotten and would not hold the load.”Footnote 32

Factories’ inefficient records might endanger employees, such as when machinery (at Corn Products and CPR) damaged limbs or burned bodies. Moreover, Witt writes: “It was becoming apparent to many that an increasing number of the victims of personal injuries, especially victims of injuries suffered in the workplace, were themselves faultless.” Consider Oswego, New York: A lawsuit against National Starch centered on a factory’s missing fire escapes, and the court syllabus noted: “An explosion occurred and fire originated from some unexplained cause on the story below and spread to the floor where she [the injured employee] was at work.”Footnote 33

Between 1902 and 1905, a Chicago fire plus two at Oswego set back Corn Products.Footnote 34 For Chicago’s 1902 blaze, the Weekly Northwestern Miller reported “the loss being placed at $400,000” and advised readers: “Five employees lost their lives and others were more or less injured in trying to escape.”Footnote 35 At Oswego, in 1904 the Morning Astorian wrote that a “fire broke out … in the chemical department and spread rapidly to the several buildings which composed the plant … the intervening walls affording no protection.” The press noted “an estimated loss of $1,000,000.” In 1905, at the same starch plant, according to the Waterbury Evening Democrat, a second “fire was caused by the explosion of a boiler.” This article closed: “The loss is estimated at $250,000.” Although optimistic, Bedford told stockholders: “At the time of the organization of your Company in 1906, the Oswego factory of the National Starch Company, its chief profit earner, had been destroyed by fire and its working capital seriously impaired.”Footnote 36 Insurance may not have covered these accidents. The press doubted Chicago’s insurance, and although one article acknowledged some functioning equipment, it also informed readers: “The sprinkler experts say that … even sprinklers cannot stop a fire when it gets a good start in an unequipped portion of the same building.”Footnote 37

Deteriorating factories reverberated on Corn Products such that its sudden inability to meet dividend expectations caught stockholders off guard. (Payments skidded from $1.92 million in 1904–1905 to $0.27 million in 1905–1906.) In August 1905, the press took note of the finger pointing over who to blame. The New York Times even reported on a lawsuit. It stands to reason that Corn Products’ managers might have lacked funds to address safety. If so, then this point returns us to problems of competition, dividends, and outdated plants.Footnote 38

A loan led to Corn Products’ final hour. Behind the scenes, as Fisher reported, by early 1906, “there was a large bank loan of over $100,000, and the Corn Products Company had no funds.” This may have helped explain why organizers established CPR and subsumed the old Corn Products under it. Promoters added 51 percent of NYGC plus two other companies. After CPR began, Fisher testified: “The directors of the New York Glucose Company declared a dividend of a sufficient amount to allow forty-nine per cent of this dividend to be paid to the Corn Products Company, and with that money they paid off their indebtedness.”Footnote 39

Infighting and Governance

Like Corn Products, CPR owners chose between allotting profits for dividends or investments. In 1906, Chicago’s Economist reported: “Those who took stock in exchange for their plants are anxious for some kind of an immediate return on their investments.” They favored dividends. As Peckham observed, there was another side to what the press called a “friendly” conflict. Bedford wrote stockholders in 1910: “It is the policy of your Directors to depend for profits … upon low costs rendered possible by large production, the employment of the most improved mechanical facilities, the use of manufacturing locations best adapted to economical distribution and the maintenance of working capital adequate for all contingencies.” In the same missive, he stated: “The maintenance of adequate working capital renders a continuation of a conservative dividend policy absolutely necessary.”Footnote 40

Aware of varied views on dividends, Bedford sought a board majority. On January 6, 1906, one document indicated that “the organization of the new company is to be subject to the approval of counsel to be designated by E. T. Bedford.” On February 15, 1906, a document indicated that eight directors (himself included) suited Bedford. In addition, a document of February 23, 1906, stated: “A majority of the first Board of fifteen Directors … shall be persons nominated by E. T. Bedford.” C. H. Matthiessen held much stock and might have tried to upstage Bedford, but he departed from the board in 1907. Other changes also followed. By 1910, three directors (including Bedford) still had ties to Standard Oil; after a Standard colleague died in 1913, his son joined. Bedford’s son was also a director from 1906 until early 1914. A few holdovers from Corn Products served, yet others such as Fisher seemed to side with Bedford. Employee managers joined the board (by my count, five by 1910). There were also a few outside directors—two financiers and an attorney. It seems then that the board shifted from being dominated by Standard Oil types to being a mix of Standard colleagues, managers, and outsiders. Although some directors were likely unaligned, or their allegiance could not be determined, various configurations might produce a majority.Footnote 41

That said, as Peckham instructed, stockholders still differed over allocating funds for dividends. One contingent held $50 million common shares, the other $30 million preferred. Dewing noted that “after allowing for depreciation and payments to the sinking fund of its bonds, only 5% has been paid, -- the dividends in arrears accumulating at the rate of 2% each year.” He considered this policy “wise.” From 1907–1908 into 1915, this meant up to $0.6 million could be used annually over the course of eight or nine years, and as will be explained, deferred dividends helped fund most plants (Table 1). Fisher described one facility: “Pekin was entirely rebuilt with a modern fireproof construction.” He offered: “Total expenditures at Pekin were $1,371,845.39.” Some investors cared about the nearly 30 percent (two-sevenths) of dividends due them, others took a long-term view. The stakes involved were no piddling affair.Footnote 42

Table 1. Plant summary, 1906–1924

Notes: Expenditures for plant upgrades included years from 1906 to 1914. Fisher answered affirmatively when prompted: “Are these figures that have been given actual expenditures for improvements and new construction?” He also indicated that “the regular maintenance costs, or repairs, as we call them, were charged right to the operating expenses; they are not included in these figures at all.” Dewing cited an undated explosion (likely before 1902) at Davenport. It stemmed from a boiler, not dust.

Sources: Frederick T. Fisher, Testimony, Sep. 27, 1915, 4513–4522, 4523–4524, quotations at pp. 4514, 4517, vol. 9, CPR, Transcript, MML; “Casualties,” American Miller, October 1, 1914, 864, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/pst.000059887966; Odum v. Corn Products Refining Co., 173 Ill. App. 348 (1912); Price, “The Starch Dust Explosion at Pekin, Illinois,” 305–320; “Corn Products Refining Company,” Moody’s Analyses of Investments. Part II. Industrial Investments 1920, 694, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/osu.32435063607055; Dewing, Corporate Promotions, 86n2; see text on Chicago (notes 35, 37), Oswego (note 36), Argo and the $10,000,000 mortgage (note 62).

In 1909, the New York Times found that “the pursuit of this policy [of upgrades] at the expense of dividends has given rise to rumors periodically that dissatisfied stockholders would seek to gain control of the management.” Despite rumors, the Times summarized Bedford’s view saying that he won a tussle; the article may be read as suggesting Bedford overcame some dissension. Concerning opposition, various permutations were possible. Differing responses likely applied to the dividend rate—5 versus 7 percent—but also distinctions between preferred and common. What satisfied some may have displeased others. As will be discussed, stockholders also would split over the size of CPR’s capitalization.Footnote 43

Bedford’s Strategies

Because CPR’s return on assets did not promise a bright future initially, Bedford acted on other strategies (Figure 1). Dewing and Peckham together identified three plans, which are detailed here in relation to owners’ disputes and safety. They entailed first, to redefine CPR’s capitalization to squeeze down dividends paid; second, to upgrade plants while limiting dividends; and third, to deploy anticompetitive tactics. From Bedford’s perspective, one strategy needed to succeed.Footnote 44

Figure 1. Corn Products Refining: Financial Measures, 1906–1921.

Notes: Return on assets (ROA) is calculated as total net income to total assets; the second measure is the ratio of long-term debts to total assets. Moody’s reports net operating income plus other income as total net income. In calculating the ROA for 1917 to 1921, I subtracted federal taxes from net income, which lowers the ROA.

As best as I can tell, income is reported before taxes (prior to 1917), interest payments, depreciation, and in some years other expenses, were deducted. The fiscal year changed in 1912 to match the calendar year; because CPR reported income for only ten months, I do not include the data point. I lack a data point for debt for 1912. For debt, which sums CPR and its “constituent companies,” I rely on the Manual of Statistics through 1917, and then Moody’s through 1921. Where available in 1914 and 1916, data points for Moody’s are lower by perhaps $2 million and tend to push the trend in debt-to-assets lower. As recorded in editions of the Manual of Statistics, data for debt did not give years; I judge data by the year of the edition as well as the most recent year income was reported. To maintain the timeline, I rely on the 1908 edition for 1906–1907 data and the 1909 edition for 1907–1908 data. I am not fully confident of the data points for these two years. Please read the chart not for precise numbers but for general trends. The figure’s main point is the sluggish pattern followed by higher returns and lower debt ratios. For Corn Products’ finances, consult text and Dewing, Corporate Promotions, chap. 4, esp. 100n1.

Sources: For debts prior to 1918, “Corn Products Refining Co.” in editions of Manual of Statistics (various dates), such as “Corn Products Refining Co.,” Manual of Statistics, 1908, 482–483, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.hntzf6; “Corn Products Refining Co.,” Manual of Statistics, 1909, 485–486, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101068324522; “Corn Products Refining Co.,” Manual of Statistics, 1910, 481–482, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/osu.32435053143087; for debts from 1918 to 1921, “Corn Products Refining Company,” in issues of Moody’s Manual of Investments. Part II. Public Utilities and Industrials, such as for 1918 data, “Corn Products Refining Company,” Moody’s Manual of Investments. Part II. Public Utilities and Industrials, 1919, 954, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951002257552f; for assets and net income from 1916 through 1921, “Corn Products Refining Company,” Moody’s Manual of Investments: American and Foreign 1922. Part II, 645, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951002257563a; for assets and net income from 1911–1912 through 1915, “Corn Products Refining Company,” Moody’s Analyses of Investments. Part II. Public Utilities and Industrials 1917, 954, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.319510022575478; for 1909–1910 and 1910–1911, “Corn Products Refining Company,” Moody’s Analyses of Investments. Part II. Public Utilities and Industrials 1914, 685, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112089430109; for assets and income in 1907–1908 and 1908–1909, “Corn Products Refining,” Commercial and Financial Chronicle, May 29, 1909, 1370, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/pst.000057718781; for assets and income in 1906–1907, “Corn Products Refining,” Commercial and Financial Chronicle, July 6, 1907, 39, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015049861910.

Option One: The Issue of CPR’s Capitalization

As a technical solution, Bedford proposed paring and reimagining CPR’s capitalization. Dewing saw the value of Bedford’s approach.Footnote 45 The press cited conflicts, however. In late 1910, the Newark Evening Star told readers that CPR’s board understood “common stockholders are dissatisfied.” As regards drawing in the capitalization, the American Miller predicted in 1911: “Many of the common stockholders will not agree to have their controlling interests taken away by accepting a few shares of the new stock to many of the old, nor that preferred stockholders will all agree to receive only 5 per cent cumulative dividends in place of 7.”Footnote 46

Three years had passed when, in 1914, the New York Times reported: “Directors and stockholders are pretty well of one mind in believing that the company would be in a far stronger financial position if its capital were cut in half, but they haven’t been able to find a way to bring it about.” Preferred and common stockholders faced varied setbacks, shaped in part by the topic of dividends. Then, the Times presented another issue: “The law provides that a corporation may not issue preferred stock unless the proceeds of the sale is used to acquire additional property.” This legal factor settled the matter.Footnote 47

Option Two: Investments

Although Bedford tried but failed to contract CPR’s capitalization, he also aimed to remake five factories and add a sixth between 1906 and 1914 (Table 1). In addition to plant upgrades, which Dewing and Peckham noted, investments might also reduce fires that resulted in explosions.Footnote 48

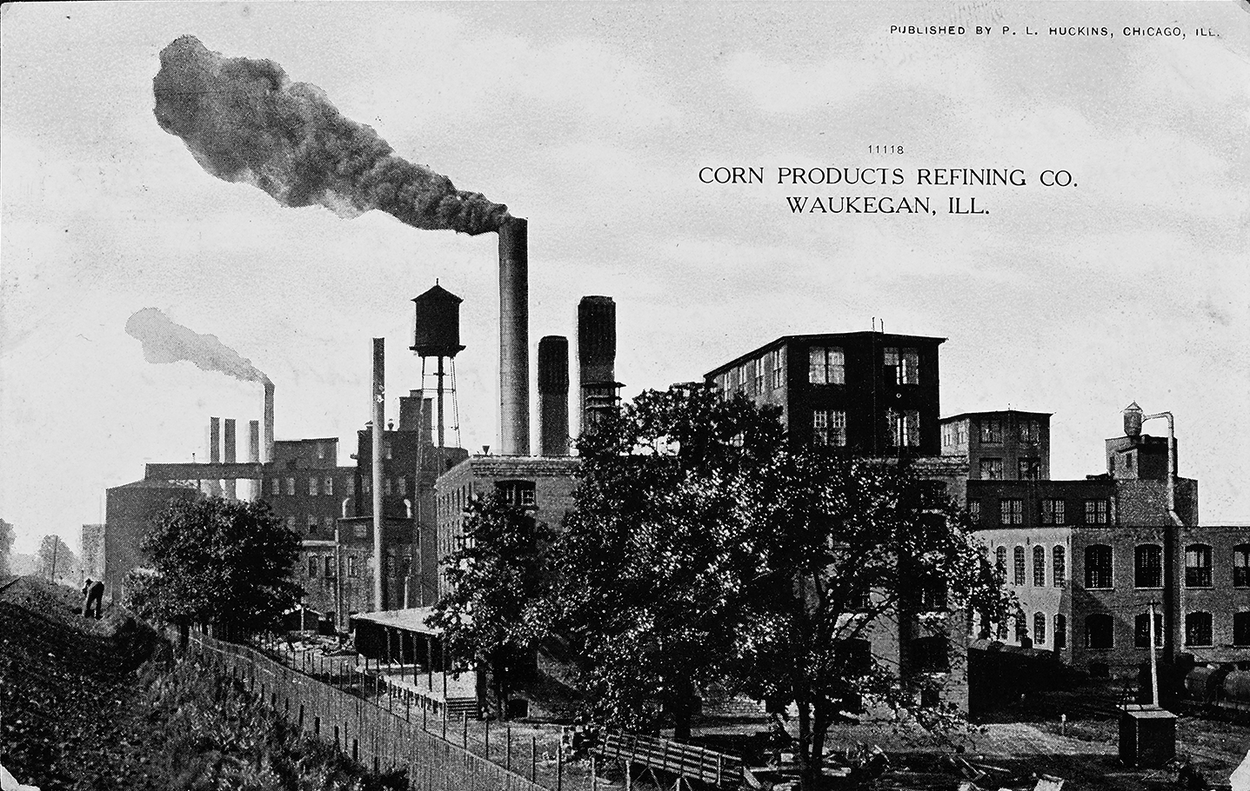

A decisive event came at Waukegan, whose buildings predated CPR’s organization. The Grain Dealers Journal related: “It was shipping day and the regular force had been doubled to hasten the filling of the box cars.” Then there was this change: “The roof went up, the walls went out and down, crumpling; … everything burst into flames.” Calling it a “starch dust explosion,” the American Miller reported: “This is the third similar disaster in the same plant within nine years.” It was a testament to rescuers that not more than fourteen died (Figures 2 and 3).Footnote 49

Figure 2. Waukegan, Ill., ca.1908. Author’s collection.

Figure 3. Explosion at Waukegan, 1912. The caption read: “Corn Products Refining Company fire at Waukegan, Illinois, November 24, in which fourteen employe[e]s were fatally burned.” Illinois State Fire Marshal, Second Annual Report of the State Fire Marshal of the State of Illinois for the Year 1912 in First-Sixth Annual Report 1911–1916, quotation at p. 32. Photograph is courtesy of The University Library, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

Shortly after the Waukegan explosion, the Weekly Underwriter wrote: “The [Illinois workmen’s compensation] law provides a benefit of at least $1,500 in cash for the death of an employee, and the sum may go as high as $3,500, dependent on the wages earned.” Workmen’s compensation laws focused on maimed individuals (assumed to be men), but a revised interpretation finds that the laws varied in their impact. Looking more broadly at safety, scholars recently pictured government agencies, manufacturers, and civil society organizations working to reduce hazards, yet their research opens new configurations insofar as the type of accident may suggest altered conceptualizations.Footnote 50 As for CPR’s factory explosions, safety outcomes hinged on both its engineers and its governance (Table 1).Footnote 51

Certainly, other entities played important roles. At the USDA “dust explosion testing station,” scientists studied “windows designed to release the dust explosion pressure in the plant before serious damage can be done.” As another example, the U.S. Geological Survey investigated numerous materials that found their way into cement.Footnote 52 In a radio address over the Farm and Home Hour (later an essay in Scientific American), USDA’s David J. Price dated efforts to a (non-CPR) factory explosion in 1913. Within nine years, these actors had formalized “the Dust Explosion Hazards Committee of the National Fire Protection Association [NFPA],” and by 1931, many had agreed on “safety codes” published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.Footnote 53

Even with this oversight, CPR was pivotal in reducing factory explosions. Some engineers may have felt personally threatened by fires or explosions and acutely aware of the need to make changes.Footnote 54 Evidence suggests they approximated or in a few instances anticipated codes written in 1931.Footnote 55 Perhaps most important, CPR engineers switched to reinforced concrete. For Pekin, Merrill testified: “We tore down very nearly all the buildings and built a new plant up in its place. The construction is concrete and steel throughout, absolutely fireproof.”Footnote 56 Referencing the new plant that replaced Chicago’s facility, its lead engineer George Chamberlain related: Argo was “strictly fireproof.”Footnote 57 These engineers had a point, as reinforced concrete promised important improvements in the early 1900s. In addition, by 1931 safety codes called for “daylight type of construction,” and Argo anticipated this requirement with its rows of large windows (Figure 4).Footnote 58

Figure 4. Argo plant construction, Argo, Ill., ca. 1909. Author’s collection.

Should a fire threaten to cause an explosion, engineers took another protective measure in detaching buildings. One CPR manager explained: “If we wanted to rebuild it [Waukegan] … [w]e would set the buildings farther apart, … and for that we would not have enough land” (Figure 2). Conversely, for Granite City, Jeffries described the value of distancing buildings: “The fire hazard was very much improved by the building of the new elevator building.” He elaborated: “The storage of any feed made from corn is liable to fires, and by putting this in a separate building the greatest hazard to the main plant was removed.”Footnote 59

CPR engineers also launched preventive strategies. Merrill noted information used to watch over plants, and Industrial Progress cited the example of Argo’s “daily power report,” which reviewed boilers, their fuel consumption, and cost measures. Perhaps more important, numerous details enhanced safety. Management turned to steel, not iron, as the metal of choice, and took steps to see oil filtered such that “foreign matter is entirely removed.” As for the ash from coal, “it is kept continuously moist to prevent dust flying about the plant.” By 1931, the NFPA made “housekeeping” a safety code given the need “to prevent miscellaneous dust clouds.”Footnote 60

A brief remark applies to asbestos used with Argo’s boilers. Difficult questions concern how extensively asbestos appeared in the complex and how exposure affected workers. Although examples of medical knowledge of industrial uses of asbestos may have dated ten years before Argo’s construction in 1909, CPR management likely was unaware of this literature. To better understand asbestos, readers can consult recent scholarship. I hesitate to assess asbestos’s impact at Argo given questions regarding its effects on workers.Footnote 61

Although safety required engineers upgrade plants, Bedford did not simply count on the firm’s return on assets for funds (Figure 1). In 1910, he laid out the mess of National Starch and hoped for a solution. At the same time, the president addressed CPR’s expenditures on key plants (Table 1). Asked about “the total for new construction or reconstruction of old plants and the building of new plants, the grand total,” Fisher said it equaled $13,933,024.76. One source of funds was a $10 million mortgage. A large part, Bedford explained in 1910, went to “the cost of the first unit of the Company’s Argo plant.” In addition, “the Directors are of the opinion,” he wrote stockholders in April 1909 “that … a sufficient amount should be authorized now to provide … for such additional requirements as are likely to arise.” The mortgage required one more step—being “authorized by vote of the holders of two-thirds of the capital stock of the Company present or represented at a special meeting … or at an annual meeting.” They agreed to the mortgage, in contrast to their disputes over dividends. Even while dividends were a source of ongoing tension, the years of deferring dividends proved important: Bedford raised sums for upgrades at five plants (not counting Chicago and Oswego). My conclusion is supported by Peckham’s analysis, which similarly cited the redirection of funds from dividends to investments. The mortgage and dividend money thus allowed for major plant improvements (Table 1).Footnote 62

Option Three: Anticompetitive Ploys

Bedford’s investments might have come to naught since his anticompetitive tactics landed a 1913 antitrust suit. Although Peckham recently reevaluated the case, the thrust of my assessment is that the court’s ruling indirectly helped shape the firm’s broader recovery. Improved efficiency, in turn, might better fund accident mitigation.Footnote 63

Writing in 1916, Judge Learned Hand rejected a few antitrust charges but still wrote that CPR’s hurtful practices included “selling the glucose secretly in competition only with the independents to injure their business.”Footnote 64 As a second example, the court cited noncompetition contracts: “In two instances … the defendants exacted contracts not to engage in the trade from the owners who sold their plants, and that this was done with the purpose of monopolizing the industry.”Footnote 65

Calling for dissolution, the opinion opened the way for developments that might generate cost savings.Footnote 66 As Simon N. Whitney noted: “In March 1919,… the defendant withdrew an appeal to the Supreme Court.” This was strategic. Moody’s told readers that, among properties, “the company must divest itself … of its plants at Davenport, Ia., and Granite City, Ill., the two Novelty Candy plants … and all its holdings in the National Starch Co” (Table 1). In 1920, securities reporter James Garrison anticipated Whitney in spotting uses for the divestiture money: “The company is constructing a new refinery in Illinois, and is building a great pier near its New Jersey property.”Footnote 67

As Garrison suggested, events broke in Bedford’s favor during World War I. CPR’s ratio of debt to assets declined while profitability rose (Figure 1). In 1918, the press reported that CPR’s lineup sold well, noting: “The only new use found for starch since the war started is in the making of high explosives.” Garrison held that “changes initiated from motives of patriotism were retained after the war in many households from motives of economy [frugality].” Fortune related CPR’s fabulous growth abroad.Footnote 68 Peckham also highlighted foreign expansion as well as innovation.Footnote 69 These developments saw CPR make the cut for the two hundred top U.S. enterprises in 1930.Footnote 70 Moreover, well before that date, investments soothed critics when, as a journalist reported, “Back dividends on the preferred … were largely paid off in 1916 and 1917.” Moody’s also noted payments. In 1919, after having been deprived so long, common stockholders received some dividends too.Footnote 71

Allowing gains in efficiency, the antitrust outcome brightened CPR’s future, yet in 1924, a plant explosion at Pekin far exceeded deaths and damage at Waukegan. USDA’s engineer Price related: “The men who lost their lives”—forty-two total—“were well known and had large circles of friends and relatives.… [T]heir loss was deeply felt.”Footnote 72 The accident demonstrated that CPR engineers were perhaps too eager in calling buildings “fireproof.” Price still stressed their contribution with respect to so-called daylight factories, which were built with huge windows. Both reinforced concrete, which CPR engineers described, and the windows, which Price highlighted, counted. Price compared two Pekin buildings: “Large window areas permitted the explosion to vent its force without damage to the structure while the solid walls of the adjoining building were demolished” (Figure 5).Footnote 73 Since these tragedies occurred, Price and CPR engineers noted the value of space. Citing “the manufacturers of powder and other explosives,” the USDA engineer advised “the precaution of dividing the plant into units.”Footnote 74

Figure 5. Explosion of January 3. Pekin, Ill., 1924. Author’s collection.

The antitrust case did not concern accidents, and although Judge Hand very briefly indicated his awareness of plant safety, it was conceivable but unlikely that safety figured directly in his decision. Instead, as events unfolded, new cost savings allowed CPR to enhance safety if owners acted. Although I do not know Pekin’s funding beyond Table 1, its accident occurred on the cusp of the downward shift in explosions by 1930. Moreover, whereas Price had called for more to be done, he also outlined how past investments had helped limit damage.Footnote 75

Conclusion

Explosions devastated workers and, unlike other types of accidents, impacted CPR finances along with the potential cost savings of factories. Price noted that Pekin’s “property loss has been estimated to be about $525,000.” He further stated, “The compensation claims amounted to approximately $175,000.” (Factory downtime also lowered efficiency.)Footnote 76

As noted, the pivotal factor was CPR. Its engineers initiated valuable improvements, but its governance was crucial. Engineers deserved credit for reinforced concrete, information checkups, design details, and better placement of buildings.Footnote 77 However, to put into effect safety ideas, they relied on Bedford to negotiate with his board and stockholders. Stockholders debated dividends versus investments, while Bedford pressed for investments. He could appreciate directors who paid 5 not 7 percent in dividends. In 1909, he could thank the board (and most stockholders) for backing the $10 million mortgage (Table 1). Then too, Bedford overcame unimpressive profits; redirected funds from dividends; altered bond instruments; and upgraded factories.Footnote 78

Testifying in 1916, Bedford stated: “I made a motto … ‘Quality, quantity, and then economy,’ putting in the plants what the railroads put on the side of their tracks, only instead of ‘Safety First’ we put ‘Quality First.’”Footnote 79 Although we do not know more about his views on safety, he might (or might not) have addressed accidents in pursuing efficiency.Footnote 80 Even if Bedford was a bit mysterious, CPR’s story still showed how governance debates among a company’s most powerful actors mattered to rank-and-file workers for their safety.