Entering the Ring

Historically, clowns have always been trained “on the job”: one was born or adopted into a circus dynasty or else ran away to join the circus, serving an apprenticeship. Breaking with the long tradition that performers learn on the job, after World War II, national circuses in the Communist bloc created their own academies; they were followed in 1974 by the École nationale de cirque founded in Paris by Annie Fratellini and Pierre Étaix, now the Académie Fratellini, and in 1982 by the Escola Nacional de Circo in Brazil. These examples led to the teaching of circus skills in universities, enabling breaches in the gender barriers between types of circus acts. For example, six years after Ringling Brothers founded a clown college in 1968, Peggy Williams was the first woman to graduate with a contract. At first she felt out of place. In an interview series for the Ringling Museum of Art, she stated that early in her training she had presumed that clowns were gender neutral: “I didn't know there weren't girl clowns. I thought being a clown was being a clown. You could be a man or woman. I had no idea what was heading my way because of gender.”Footnote 1 Although she learned under the auspices of great clowns such as Lou Jacobs, she was left to her own devices to craft a clown that reflected her allegedly female nature.

“All the clowns that were my mentors who played female roles . . . were men in drag.”Footnote 2 That led her to subsequent disputes about costuming when she refused to pad her breasts and buttocks as they had done. When she began touring, she was the only woman clown in her unit, and the managers rarely knew how to classify her. For example, she was not allowed to dress in the ladies’ wardrobe because the powder in her makeup threatened to ruin the many sequins adorning the other women's costumes, and the men's dressing room was off-limits; so she was segregated in her own private quarters. In this case, a “room of one's own” was not an advantage.

Williams commented that she did not fit neatly within the press's expectations either. One reporter in, predictably, Berkeley, California, asked her to have her picture taken in clown makeup burning a comically oversized bra in front of City Hall. Williams refused. “I'm a clown,” she said. “And we don't get political.”Footnote 3 As she had done throughout her career, Williams straddled multiple rings and, in this instance, refused to align her personal progress with prevailing social movements. Nevertheless, her statement raises the question: Given their historic scarcity in the ring, are women clowns not inherently political? And, if so, what are the politics specific to performing as a woman clown? These questions have been addressed by the movement known as the nouveau cirque, a reformation of circus aesthetics and practice that began in the late 1960s and moved away from the structure of a traditional circus show, taking instead a multimodal and narrative-driven approach more akin to “legitimate” theatre.Footnote 4 Our concern is to explore the earlier challenges, questions, and comments made when women first started to perform the clown in the ring beginning in the mid-nineteenth century.

Through a survey of writings and reports of the female clown from that period to the first half of the twentieth century, this essay inquires into the rhetoric surrounding the woman clown, and how her presence routinely challenged perceptions of the role and definition of the clown. If clowns “don't get political,” as Williams protests, neither do they evade the assumptions projected onto any performing body. Even when they did not actively perform femininity, the very presence of their bodies beneath the costume, wig, and red nose created mischief—behavior that teases, rattles, and annoys—by revealing the performative and discursive relationship between woman and clown. In essence, until the latter half of the twentieth century, to be both a woman and a clown was a paradox, one that reveals a host of attitudes related to the very nature of the clown archetype within the circus.

In her study of circus bodies, Peta Tait argues that the aerialist act resulted in a “double gendering,” one that attempted to reconcile the seemingly paradoxical requirements of the act: muscular power coupled with grace. Though the double gendering challenged preconceived notions of masculinity, it was even “harder to reconcile” with women. “At issue,” Tait asserts, “is the extent to which a spectator viscerally perceives the physicality of another body (or other bodies) in a process of oscillating identification and disidentification with its cultural identity.”Footnote 5 Although less concerned with physical qualities, the same double vision occurs with female clowns, influenced by prevalent attitudes regarding their aptitude for buffoonery, mockery, foolishness, and slapstick. The presentation of a different type of body in the clown formula introduced a new setup to a well-worn gag. Some took slaps, tumbled, and performed slapstick. Others caricatured masculine behavior, performing awkwardness, stupidity, and clumsiness. Though they may not have had this explicit goal in mind, each of the pioneering women we discuss subverted assumptions about the clown, especially that its gender is exclusively male. Nor is it gender neutral, however, because when a woman adopted its role, its schema shifted alongside her performance.

The None and Only

Our method is to review a collection of publicity, interviews, newspaper articles, human-interest pieces in trade publications, and comments from women clowns themselves. For purposes of definition, we take “circus clown” to mean a costumed and made-up persona, performing professionally within a circus ring or under the auspices of a circus management, and engaging in physical or verbal comedy. Because the circus is an international phenomenon, we refer to examples from the United States, England, France, Switzerland, and Brazil. We recognize that this wide-ranging view comes with its own limitations. A smooth, linear trajectory across continents is not easy to follow, and it is difficult to establish the influence of one clown on another (indeed, many women boasted they were without peer). Instead, our intent is to offer a motley of examples. We link the narratives and themes related to the early line of female circus clowns, one that is by no means exhaustive but revealing of patterns that supersede cultural and national boundaries.

To complicate matters further, the employment of the clown is multifaceted, sheltering under its tent a wide variety of genres and skill-sets. The women discussed in this paper performed various types of clown activities, from singing to knockabout. Some performed in male disguise, hiding their gender completely. Others played up their femininity as an aspect that heightened their comic charms. Those who first adopted the role had to counter prejudices, willing to perform slapstick and horseplay when it was considered indecorous for them to do so. They also ran up against circus tradition that relegated women to more graceful and choreographic functions. To clown, these women had to put aside normative standards of femininity (grace, beauty, modesty) and assume so-called masculine prerogatives of aggression, troublemaking and awkwardness. While this boundary crossing did not explicitly express a feminist program, it suggested that women were capable of exercising such qualities, at least in the ring.

Until very recently, even scholarship on clowning has overlooked the contributions of women. Print publications are largely mute on the subject. Earlier important works such as John Towsen's 1976 survey of clown history Clowns and George Speaight's The Book of Clowns (1980) make hardly any mention of women clowns in the circus.Footnote 6 Even when they are addressed the discussion is usually relegated to a few lines or pages. Information is scarce and easily distorted. For instance, the iconic clownesse invariably cited is Cha-U-Kao, her frizzy wig and black tights familiar because Toulouse-Lautrec immortalized her in paintings and lithographs. Yet she was not a clown. The name Cha-U-Kao is not a Chinese derivation, but a pun on Chahut-Chaos; a chahut is a high kick in the cancan. She was a contortionist who first appeared in 1895 at the Moulin Rouge in Paris; only then was she hired by the Nouveau Cirque, in whose ring Lautrec portrays her (Fig. 1).Footnote 7 Using the term “clown” broadly, Anna-Sophie Jürgens in her recent essay seeks to find historic examples in venues like the theatre, cabaret, vaudeville, and music hall. She posits that cross-dressing male clowns may have paved the way for female clowns. She also points to literary examples such as Félicien Champsaur's pantomime Lulu (1888).Footnote 8 But evidence shows that women had their own flesh-and-blood models in the circus as early as the 1850s.

Figure 1. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, “Entrée de Cha-U-Kao,” 1894, lithograph. Printed in Le Rire, no. 67, 15 February 1968. Collections Jacques Doucet, Bibliothèque de l'Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, Paris.

Documentation is problematic. Mistakes and misstatements abound in the journalism that often provides the only easily accessible testimony to a clown's existence. Josephine Evetta Matthews is called Miss Williams in one newspaper and Mademoiselle Adella in another.Footnote 9 Catherine Parkes is renamed Caroline Parkes.Footnote 10 Miss Del Fuego is Lulu in one publication and Myrtle in another.Footnote 11 “Our Dolly” may or may not be married to a Mr. St Leon (which member of this extensive circus family?). Others go unnamed. The popularity of the name Lulu or Loulou only confuses the matter.Footnote 12 Some of the women who called themselves clowns performed the role for only a brief time. Those who concealed their gender under male garb may never have been identified as female by audiences or the press.

These problems become compounded while archival challenges, circus conventions, and attitudes toward gender obscure the female clown from view. The first major historiographical inquiry comes from Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene in their book Women of the American Circus, 1880–1940 (2012). In an important section, they present evidence of many women clowns in the United States from the mid-nineteenth century. The earliest recorded by circus historians is Amelia Butler (1833–69), who appeared in James M. Nixon's Great American Circus in 1858. The advertisement for the 14–16 June events proclaims in large font, “Lady Clown to the Ring.”Footnote 13 Other pioneering figures Adams and Keene mention include Maude Burtoli, Miss del Fuego, Evetta Matthews, Agnes Adams, Laura Silver, and Loretta La Pearl. An early female clown in the United Kingdom was Mary Ann Maskell (1843–1913).Footnote 14 First sighted in 1867, she performed as “Ada Isaacs,” for the better part of a decade earning positive reviews and “outbursts of applause.” Evidently a “talking clown,” she was praised for her feminine touches: “her ‘lady’ diction is elegant, her wit refined and incisive, and her elocution superior.”Footnote 15

However, the presence of these women in the circus was frequently elided by the press and publicity agents in their quest for an eye-grabbing headline. Even before P. T. Barnum's use of humbug to exploit the audience, the circus was in the business of creating its own myths and disseminating them as widely as possible. Adams and Keene thus reveal that the circus has had many “first” and “only” female clowns in the world.Footnote 16 Their historic novelty was often a way to advertise these women to audiences from the mid-nineteenth century all the way through the mid-twentieth century, even when it was patently false. Fallacious statements from professionals have only muddied the waters.Footnote 17 For example, Roland Butler, Barnum & Bailey's chief press agent, announced Lulu Adams in 1939 as “First time we've ever had [a female clown]. . . . First time anybody's ever had one. . . . First time there's ever been one, in fact.”Footnote 18 This statement of course ignored Barnum & Bailey's own tradition of incorporating female clowns. Fifty years earlier, the management had advertised another female clown, Evetta Matthews, as the “the only lady clown on earth.”Footnote 19 According to Gillian Arrighi's often-cited article, the impulse derives from the deliberate intention of the larger circuses to turn their rings into centers of modernity. Always striving to be in the forefront of innovation, they sought to offer themselves as conduits of the newest and latest in every regard.Footnote 20 The result was the erasure of significant developments made by women. These advertisements boasted of a form of modernity, but one that, ironically, refused to evolve.

By displaying talented women, the circus sought to associate itself with the latest social movement. It dubbed a section of its show “The New Woman Supreme in the Arena,” featuring lady clowns, equestriennes, female ringmasters, and women in bloomers. Janet Davis has discussed the many ways the circus has attempted to exploit the women's movement at the turn of the twentieth century, even christening a giraffe as “Miss Suffrage” in 1912. These gimmicks aside, Davis argues that “the marriage of suffrage and circus was most effectively conveyed through the performers themselves who embodied a bracingly modern image of strong, independent womanhood.”Footnote 21 During its international tour in 1898, this feature of the show made a sharp impression in England. One eyewitness wrote that “the very sight” of a woman as a clown was “a wonderful experience.”Footnote 22 Another, reporting their success in being funny, renounces any attempt to figure out why this should be so.

Lady clowns, three of them, prove a decided novelty in the circus. To all intents and purposes they are just the same as other clowns, but the novelty of the feature consists in their being women. How a woman can act so comically as to provoke laughter from staid and stoical husbands is best answered by going and seeing these versatile women perform. That they do cause such to laugh is a fact beyond peradventure, going so far as to include the confirmed sceptic and making the latter hold his sides with laughter. Ladies and children, too, are seized with the epidemic of humour, when, at times, these clever ladies are seen in some antic or caper, dance or mad-cap frolic, or heard in some comic talk of their own devising.Footnote 23

One would think such a demonstration would be accounted a watershed moment; yet, throughout the twentieth century, the circus continued to neglect it. In the business of justifying its own novelty, Barnum & Bailey had little incentive to disclose that women had been and were continuing to be employed as clowns. It opted instead, through its own organs of publicity, to protect and promulgate the myth circulating about the absence of the female clown.

Even though there were several women performing as clowns in the past two centuries, they were still a distinct minority. Louise Peacock notes that “there were never enough female clowns in one place for long enough for them to be able to influence each other.”Footnote 24 Hence, when Peggy Williams was trained in the late 1960s, there was no available tradition. In Serious Play: Modern Clown Performance (2009), Peacock has attempted to account for the historic lack of women clowns in the business by suggesting that, in a patriarchal society, women have been reluctant to make themselves look ridiculous, act buffoonish, and give up what status and respect they commanded.Footnote 25 Clowning encourages the performer to embody a preexisting ideal. Delphine Cézard, both a feminist critic and a circus artist, has categorized the social and artistic archetypes of “clown” and “woman” as historically opposed. Attitudes toward gender, laughter, beauty, grace, and the body compel the clowness to confront (implicitly or explicitly) “a triple process of legitimization: as women, as clowns and as women who practice the art of clowning.”Footnote 26 She argues that when the production of comedy is associated with masculine qualities and women who produce it are judged by standards of femininity, “it is no surprise that women are automatically rather hesitant to enter clown territory.”Footnote 27 The tension between the categories creates disturbing barriers to this entry.

The dearth of female clowns was also due less to a lack of ability than to a lack of training. The traditional circus structure did not accommodate the formation of a female clown. Women in the circus were normally expected to be light and ethereal, not down-to-earth. Their primary functions were as riders, acrobats, ropewalkers, trapeze artists, and contortionists, their beauty and ostensible fragility enhancing their technique. Some who became clowns were first featured in equestrian acts, as was Amelia Butler early in her career.Footnote 28 The French clown Miss Loulou worked as a danseuse de corde (i.e., tightrope dancer).Footnote 29 Lulu Adams performed musical acts with her family in various circuses in England, playing the clarinet, saxophone, piano, cornet, drums, and even the bagpipes—a skill she would exploit in her clowning years later.Footnote 30

How the circus clown developed also contributed to male domination of the form. The earliest circuses were equestrian shows, and the clown began as a rider executing such feats of comic horsemanship as the “Taylor of Brentford” routine, which involved the mishaps of a bumbling rider matched with a stubborn steed. He eventually is thrown and chased around the ring by his horse. These acts involved levels of expertise often gained in the military. Eventually, the clown dismounted and began to banter with the ringmaster, and equestrian acts started to feature ethereal young women. Very soon the metonym for circus was a trio, seen in all sorts of images: the grotesque clown, the uniformed ringmaster, and the sylphlike equestrienne. In Freudian terms, they may be viewed as the Id, the Superego, and the Ego: the atavistic, uninhibited clown, the disciplinarian ringmaster, and the executrix of graceful stunts. The female figure, impassive in a gauzy ballet skirt and bare arms, stands for a kind of classical perfection, poles apart from the motley, disruptive mirth maker. Male gymnasts and equestrians often masqueraded as girls to increase the sense of danger and sexual allure (Omar Kingsley as the rider Ella Zoyara, Sam Wasgate as the trapezist Lulu Farini). Conversely, if a woman is needed for comic effect, the male clown often parodies her. With this configuration firmly established, a woman clown had to be careful not to imbalance the equation.

Once the clown withdrew from the equestrian act to excel at acrobatics or patter—a mid-nineteenth-century development—the invention of the grotesque auguste as a foil to the white-faced clown conspired further to exclude women from the ranks of clown. The white (i.e., white-faced) clown is the elegant, masterful straight man; the auguste the bumbling, childlike yet shrewd fall guy. According to Tristan Rémy, women have more ably adapted to the former role because its attributes encompass grace, buoyancy, and agility. Fewer women have, until recently, taken on the ragged mantle of the auguste.Footnote 31 His stupidity, clumsiness, and drunken behavior are at even greater odds with social constraints on women. The costume contributes to this as well. The white clown, despite the makeup, retains a human form and figure, often adorned with spangles and ruffles; a feminine physique is not necessarily camouflaged. Some women in this role have even resembled porcelain dolls. The auguste, on the other hand, evolved from a parody of the ringmaster's uniform and, later, evening dress, to a tramp, a zany, a ragamuffin. The ill-sorted, often tattered clothes, the red wig and nose, the floppy, oversized shoes make the human figure gawky, oafish, and unhousebroken, traditional characteristics of the uncouth male.

Once the white clown teamed up with the auguste the basic contours of the modern clown act came into view. The Parisian pairing of the English clown Foottit and the Afro-Cuban auguste Chocolat was among the first to crystallize the combination, building comedy around a pattern of abuse. Chocolat served as the cascadeur or stuntman, the one who gets slapped. This duo became the standard structure for clown acts in Europe (in North America the solo auguste became the star). The slapstick and knockabout of the harlequinade were incorporated into the gymnastics and backchat of the arena to form the modern clown entrée. Given these traditions, the female clown was challenged about her suitability to take on the business.

The Comic Body and Gender Prejudice

The sexist biases against female clowns were not only prominent at that time but persisted throughout the twentieth century, and linger even now. Many old prejudices relating to the female body conditioned the ways in which female clowns were admitted and judged. “Comedy is at loggerheads with the feminine virtues,” complains the Swiss clown Gardi Hutter, who began work in the 1980s. “A woman must be gentle, quiet, understanding, inconspicuous, subordinate to the man, protective . . . and motherly—the very opposites of comedy, which reveals, demotes, unmasks. . . . A woman must be introverted, and since tragedy is introverted, there are some great tragedians. But comedy is extroverted.”Footnote 32 By this logic, comedy must be loud, brash, and confrontational, and, therefore, exclusive of the feminine. Hutter's argument chimes in with many similar statements made at the beginning of the twentieth century. The notion that a woman has to surrender her femininity if she wants to engage with comedy has a deep-rooted history with the same points made again and again, without much additional nuance whatever the period. At the end of the twentieth century Joan Mankin of the Pickle Family Circus commented on the fact that a lot of her comedy “traded on the idea of women doing work which customarily was done by men.”Footnote 33

Social attitudes to such behavior excluded women from the role, a fact embedded in common responses when female clowns did appear within the circus ring. Arthur Munby wrote in his diary for 1862 that he saw Catherine Parkes perform a clown at the London Pavilion music hall, “with face bedaubed and broad grin, & thus dancing a clumsy dance.” Parkes clearly felt the need to distinguish her clowning from her male counterparts, apologizing to the audience “for not standing on her head or doing the other clown's tricks; saying ‘I, being a lady, turn my toes in instead.’”Footnote 34 No matter the disguise that the clown costume and makeup afforded, those like Parkes acknowledged that their gender made an impact on the kind of work they performed, and standing on their head was simply out of the question.

Although the audiences of popular entertainments are thrilled by novelty, they are also charmed by the familiar. Consequently, while the introduction of a female clown into traditional numbers might serve as an occasional lure, it was also disruptive to the conventions of the well-known gags and acts. The historic role of the woman in the circus to provide beauty, grace, skill, and elegance was at the antipodes to the clown universe. A couple of French essays sum up both the ignorance of precedents and the prevailing prejudices. An article of 1926 is entitled “Il n'y a pas de femme clown. Vous êtes-vous demandé pourquoi?” (“There is no female clown. Have you ever wondered why?”). Its author, André Suarès, begins by asserting, “So far no woman has ever been a clown.”Footnote 35 A mystical poet and colleague of André Gide and Paul Claudel, he may be excused for unfamiliarity with the field. (By the time he wrote the article, there had been, as we have seen, quite a few women clowns.) Suarès argued that the feminine gender was by nature inimical to clowning. “The art of the clown is founded on the power of being spectator of oneself and the ability to provoke or to have an honest laugh at oneself. Not with a complacency which mixes the laughter with three times as much incense. To be capable of making oneself a laughingstock, of making game of oneself, nothing is farther from womankind.” His reasoning depends on the notion that women are susceptible to flattery and vanity, too eager to be coveted, desired, and adored. If the tendency to mock exists in women, Suarès argues, then it is in her cruel disposition to taunt her rivals, that is, other women. “For a man to be a clown is to multiply himself, a hundred times, if need be. For woman to be a clown would be to betray herself,” he writes. “She adores herself so as to be adored, poor creature!”Footnote 36 For Suarès, women would have to renounce their very instincts to inhabit the clown. Such clichés about women's natures were supported by those about the female body that cast doubt on her viability as a comedian and a buffoon.

Engaging with such imbedded suppositions, pioneering women clowns introduced an element of gender mischief into the clown formulation. It resembles Judith Butler's familiar notion of performative gender identity. Depending on how femininity is performed and who performs it, woman is “an ongoing discursive practice, it is open to intervention and resignification.”Footnote 37 So is clown. As with commedia masks or other theatrical archetypes, there exists within the role what Michael Quinn refers to in formalist terms as “still movement.”Footnote 38 Although it retains many identifiable features over time, the clown perpetually evolves according to talents, styles, and personalities of those who play it. A performance of a “male” role, such as a clown, even when the woman in the role may or may not have been signaling her gender, rattles the historical preconceptions through an embodied alternative.

Touching on the novelty of the female clown, a reporter for the San Francisco Figaro in 1872 sarcastically connected her emergence to the progress made in the women's rights movement: “The cause is progressing. Woman is rapidly winning her way in the contest she has begun to emancipate herself from the tyranny of ruthless man. . . . The position of circus clown, which has been from time immemorial the birthright of proud man, is no longer his exclusively.”Footnote 39 No information is given as to the clown's name, the circus in which she works, or where and when he saw her, but the writer does describe the kind of clowning performed. Once again a strong contrast is made between ideals of graceful femininity and the brutality of clown acts.

A lovely being of the gentler sex has adopted the bismuth and rouge of that famous utterer of stale witticisms, and with the appropriate allowance of spangles on her dress has bounded head over heels into the tan and sawdust of the equine arena. She fondles the stuffed baby and sits down on it and explodes the concealed air bladder with rare effect. [She also] crams her capacious pockets with everything from a string of sausages to a leg of mutton, with irresistible grace[,] and executes “flip-flaps,” “ cart-wheels,” and “jim-jams” [full-body quaking] in the highest style of art. Here is a sphere of usefulness: thrown open to the oppressed and tender creatures, which, we trust, will not be neglected.Footnote 40

All of the qualities described here fall neatly within the realm of the “unruly woman,” a trope whose presence in the arts dates back to the Middle Ages. The unruly woman, according to Kathleen Rowe, revels in disorder, drawing attention to herself, speaking too loud, eating too much, dominating others, and making a spectacle of herself.Footnote 41 In this case, our clown crushes a baby, stuffs her pockets with meat, and bounces about the ring, the same type of maniacal actions that the progenitor of the clown, Joseph Grimaldi, performed in English pantomime.Footnote 42 Through her clowning, the “lovely” and “tender” individual, as the reporter describes her, acts in direct discordance with these characteristics. She exceeds the bounds set for femininity, behaving in a brash, violent, and chaotic way. Because her gender remains conspicuous, the contrast causes disruption and discomfort, which in turn leads to laughter. It is as a woman that the grotesque nature of her clowning takes on a special tinge.

Trailblazers

Jürgens claims, “[W]e have little insight into [the early clownesses’] conception of clowning, sense of female clown identity, and the importance of self-expression.”Footnote 43 Our archival findings offer cogent perspective on these points. We now look to several examples of successful women clowns, such as Evetta Matthews, Miss Loulou, Lulu Adams, Loretta La Pearl, and Annie Fratellini, who teased and subverted the preconceptions linked to the clown by being crass, buffoonish, violent, mischievous, aggravating, and, most of all, women. Some women showed an aptitude toward clowning because they were outspoken and displayed impressive strength. They were thus capable of causing the requisite ruckus.

Like many of the early female clowns who found their way into the craft either as children of clowns or married to a clown, Evetta Matthews (ca. 1870–?) was the daughter to an English clown who had been working for forty years, twenty with Barnum & Bailey. Evetta Matthews had an international career. She began in pantomime in England, where she also performed as a gymnast. She took a brief stint in Paris and then played America in 1895. Three of her brothers were also clowns and would often come to her for ideas. Eventually, she says, “I thought that I would become a clown myself and make use of the suggestions I used to furnish them.”Footnote 44 Not built for the traditionally lithe and limber roles of the female circus artist, Evetta Matthews was described as “short and plump and remarkably muscular.” One of her early feats was to lift six of her sisters onto her shoulders, “a sort of female Sampson [sic].”Footnote 45

In the late nineteenth century, the French had revived pantomime as a high-society diversion with a decadent erotic tinge. Its Colombine, who appeared in much popular imagery, was a winsome hoyden sporting a white topknot (not unlike that of a cancan dancer), frills, and tutu above black-stockinged ankles. Judging from posters and photographs one finds that Evetta Matthews, who had spent two years at the Paris Hippodrome, adopted that as her clown costume with a minimum of makeup and with baggy pantaloons in lieu of tutu (Fig. 2). Diminutive in size with a voice difficult to project, she relied chiefly on tumbling, cycling, and swinging Indian clubs. Her standard clown routine was to muffle herself in bonnet and cloak, sit next to an innocent young man in the audience, and then shout to the ringmaster for a job. They begin to haggle:

Figure 2. The Strobridge Lithographing Company, American, Barnum & Bailey: Evetta Lady Clown, 1895. Ink on paper, 1 sheet (V): 38¼ × 28¼ in. (97.2 × 72.4 cm), ht2000167. Collection of the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art Tibbals Collection.

Evetta: How much will you give me?”

Ringmaster: “Ten dollars a performance.”

Evetta: “Oh no! the young man here that I am engaged to will give me more than that to stop here with him.”

The young man in question is duly embarrassed until she throws off her disguise and leaps into the ring.Footnote 46

Provoking embarrassment in the male spectator by pretending to be his sweetheart, she is loud, intrusive, outspoken, and forward in her pretentions. In the act, her clown does not hide her gender but behaves as the traditional unruly woman to create mayhem by pressuring her two male targets: the ringmaster (who is in on the bit) and her beau in the audience (who is not). Evetta Matthews adopted a feminist guise for her clowning, explicitly presenting herself as a “New Woman” qua clown, disregarding the “stern judgment” and “prejudice that only the odd—feminist, difficult, ugly, unnatural—woman would take on such a role.”Footnote 47 Evetta Matthews's recorded remarks suggest a feminist cast of mind:

I believe that a woman can do anything for a living that a man can do, and do it just as well as a man. All my people laughed at me when I told them that I was going into the ring as a clown. But they do not laugh now, when they see that I can keep in an engagement all the time and earn as much or more money than they can in other branches of the business. I am paid for my ideas. Every day I try to think out something new, and the management usually gives me pretty wide latitude.Footnote 48

Her clever turn of phrase indicates an ironic shift in the reception of her work. It was when she successfully made a buffoon of herself that people took her seriously. Despite Evetta Matthews's insistence, the article undercuts her argument, issuing that “[t]he men in the clown business rather enjoy [her] antics, but they do not regard her as a serious competitor or believe that any other women are likely to follow her example.”Footnote 49

They were wrong, in fact. As Evetta Matthews was building her career in the early 1890s, performing for Rowley's Circus throughout the English countryside, she had a local competitor: a singing lady clown known as “Our Dolly.” Dolly performed in the provinces at Quinette's and Newman's Circuses, and, like Evetta Matthews, shuttled between the circus and pantomime. When she appeared in George Sanger's panto at London's National Amphitheatre, the columnist Peter Pickup believed that she would inspire many imitators:

“Our Dolly” is certainly a novelty, and a very pleasing one. A talking and singing lady clown is quite a new thing in the circus, and those who visit Sanger's—everybody, in fact—will declare they never heard “wheezes” more humorously “cracked,” or saw the pantomime tricks of the ring—the good old traditional “business”—more gracefully performed. Of course, there will be lots of “talking and singing lady clowns” now; but please remember the real, original, bona-fide one is only to be seen at “Sanger's.”Footnote 50

Our Dolly acted as a female jester, in the style of the self-styled Victorian “Queen's Jester” William Wallett, her comedy more verbal than physical.Footnote 51 Alleged to be wife of another clown and horizontal-bar performer, a Mr. St Leon, she seems to have had limited success, since she disappears from press notice thereafter.

In the United States, many women followed Evetta Matthews's example. Even though Barnum & Bailey had advertised her as the “the only lady clown on Earth,”Footnote 52 two years later, its route book emblazoned Jessie Villars, Lizzie Seabert, and Lonny Olschansky, “three queens of the mimic world” as “the Only Lady Clowns on Earth.”Footnote 53 Olschansky even affected a costume similar to Evetta Matthews's, which may contradict Peacock's claim that early women clowns had no influence on one another. Nonetheless, Barnum & Bailey's elision of female clowns both marketed their singularity and yet downplayed their viability.

Evetta Matthews professed no long-term plans to pursue a career in the circus, however, but hoped to be married someday and lay aside the clown makeup: “Every woman does. But I do not believe in women sticking to the business after they are married, though the rule in a circus seems to be just the reverse.”Footnote 54 To this point, Cézard posits that many early female clowns were in the otherwise inaccessible profession because marriage created an avenue of opportunity. Beyond family obligations, she suggests, it would have been unlikely for these women to have entered and stayed in the field.Footnote 55

Violence and Mischief

Skeptics like Suarès argued that few women engaged in clowning, not only because their feminine nature was at variance with its fundamentals, but also because the female body is equally inapt to execute its physical requirements. Not for a lack of strength, but because “the clown always ends by fighting and being beaten. And it is well known that one must not beat a woman, not even with a flower.”Footnote 56 However, Loretta La Pearl contradicts the axiom that a woman may not be struck: getting slapped by her husband was a routine part of the act. After studying the piano, La Pearl turned to clowning in the 1920s, ostensibly on account of her husband.Footnote 57 “Loretta La Pearl became a clown because she married one seven years ago. She wanted to be with her husband, but he told her there was absolutely no demand for women clowns. ‘Then let me make up as a man,’” La Pearl retorted, “‘and clown with you Joeys from Clown Alley.’”Footnote 58 The tactic worked, for she became a permanent feature. Similarly, in the 1920s Yvette Spiessert joined her husband, Marcel Léonard, and brother-in-law Eugène as a clown in the Léonard Trio at the Pinder Circus. According to Tristan Rémy, she added “a tinge of gentility” to the act, “which contrasted with the aggressive clowning of Eugène.” However, her audience would not have known she was a woman because she dressed in a male costume and makeup. “None of the spectators, apart from the initiated, could ever guess that beneath the character in the top hat and horn-rimmed spectacles was a female presence.”Footnote 59 One commentator used the word “camouflage,” suggesting this manager's daughter was deliberately concealing the fact that the laughingstock was a woman.Footnote 60

In the United States, La Pearl adopted the strategy to fit in among the motley, which may have also guided her approach to physical comedy. She spoke at length about her diligent training in the art of the slap, perfecting the technique over a period of many years:

[T]he clowning trade like any other trade is filled with tricks. The first trick I learned was how to save myself. You see me do some knockabout stuff and funny falls when I am working on the center stage. Well, when I began to study to be a clown and [my husband] Harry told me to fall, full length, upon the floor, I nearly broke my back, or thought I did. But by and by I learned the trick of making my rounded shoulders take most of the blow. Now I can fall or sprawl almost any way without suffering the least bruise.Footnote 61

She contends that a well-performed slap should cause no pain at all. The whole sequence is a sleight of hand whereby the victim of abuse turns the cheek at the right moment and makes the sound of the slap with hands positioned out of view of the audience. However, she also relates an anecdote about working with a novice clown in difficulties:

Now and then Harry joins out an amateur, a youth who is known in his first season as a “First of May.” Such a youth has confidence, but lacks judgment. We had such a one on our show last spring. He was supposed to slap me, and he did. My cheek stung for many an hour. Another First of May was instructed in slapstick exercise. The slapstick, whether it has a detonating cap or is merely made to give forth sound by flapping its two parts together, is not supposed to hit its victim hard. If you'll watch an old clown working in the ring, you'll see that this is so. But this particular First of May wanted so much to make good that he belabored Harry until we had to poultice him.Footnote 62

Despite precautions, clowns did hurt each other, particularly those without proper experience and training, and no matter the implicit attitudes concerning slapstick and the female body, La Pearl's testimony proves that some female clowns were not immune to the hard knocks and took the risks and the hits willingly for the sake of comedy. Still, given the prevalence of comic violence in the circus, part and parcel to the art of clowning, critics and audiences alike bristled at the seeming abuse of the female clown.

While some women like La Pearl hid their gender under greasepaint and silken clothes, Miss Loulou (1882–1975) used her femininity as part of the clown act. She played with a youthful, androgynous quality. Gender-bending was part of her mischief. She was born Héloïse Palmyre Bertin, illegitimate daughter of a bear trainer. Her first work in a circus was a dancer, known professionally as Mlle Permané, first in the ring, then on a rope; in 1905 she married the lanky acrobat Charles Auguste Deconsoli. While she was at the Cirque Despard-Piège, she found her husband employment as a rubber-limbed auguste, working with the stilt-walking clown Joé Caschmore. He took the stage name Atoff (i.e., a toff, a gent, a sign of both the Anglophilia of French society at the time and the type of dude or Gigerl clown popular in the German-speaking circus); later, when partnered with Jean-Marie Caïroli, he annexed that name as well. After World War I, Atoff-Cairoli worked as a between-films attraction in Italian cinemas with the white clown Ferruccio. When Ferruccio fell ill, Atoff needed to honor his contracts, and so Mme Deconsoli was rechristened Miss Loulou and joined the act.

They performed a simple and amusing musical number, “Am I Singing or Are You?” After touring Italy, in 1922 they were signed by the director of the Cirque Médrano in Paris to compete with the Fratellini and the new team of Chocolat Jr. and Porto. As Gustave Fréjaville enthused,

When the Médrano reopened in September 1922, we were surprised to see appear in the area an authentic clowness (I don't think I would have hesitated to write a clown) dressed in the spangled sacque and wearing the little white felt cone of circus clowns. . . . The program announces Loulou and Atoff, clowness and auguste. And here is a neat and nimble creature, both a classic clown and an elf from a fairy tale, who maintains with charming self-confidence the role of pattering clown. . . . Boyish and graceful, light, ironic, impertinent within bounds, in a bright and merry voice which carries almost to the farthest benches she flings with an unpretentious sprightliness very captivating comments on the deeds and gestures of Atoff; she is Ariel to his Caliban. This artiste of French origin has created a singularly new and vivid character, cousin to the immortal Gavroche and the Fantasio of Roubille, great-grand-nephew of Cherubino and the racy allure of a complete Déjazet.Footnote 63

Fréjaville's detailed report is worth comment itself. The aside regarding the term clowness acknowledges that Miss Loulou's work needs no gender marker, that she ranks as a clown, and yet her singularity as a woman calls for a distinction to be made. Miss Loulou is cast in the white clown role (Fig. 3), which traditionally controls the dialogue, like the leader in a dance. To this usually strict and aloof personage, she brought a buoyancy and charm which the critic associates with sprites and pubescent males.

Figure 3. Miss Loulou, printed in La Rampe, 15 March 1926. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

He suggests that Miss Loulou has leavened the white clown with the grace of the female acrobat. Fréjaville has recourse to a host of literary allusions to conjure up images of adolescent sexuality and impudence: the amorous hobbledehoy Chérubin/Cherubino of Beaumarchais's and Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro, Hugo's street-smart urchin in Les Misérables, and the pert grisettes of Roubille's covers for the humor magazine Fantasio. As to Mme Virginie Déjazet, for decades she played hormonal male teenagers on the French dramatic stage. In other words, Miss Loulou brought to the clown act as whiff of underage sensuality. Later Atoff added Chocolat Jr. to the team, which played all the leading circuses, including Hagenbeck's and Barnum's. Charlotte Blanqui, who regularly covered the circus for professional journals, wrote that “Loulou has no rivals. The only female clown in Paris at Medrano's, she reigns without competition and without jealousy. Why?” Blanqui uses the example of Loulou to maintain that “woman can excel there as anywhere else. It's indisputable. . . . But why, yes, why, has Miss Loulou no imitators?”Footnote 64

Matrimonial Grief

Marriage proved to be the door through which most female clowns could enter, since the white clown–auguste tandem offered a handy medium for a husband–wife team. A model already existed on the variety stage: it was not uncommon for married couples to appear in song-and-dance and magic acts. The benefits of clowning with one's spouse are numerous. The couples develop a deep sense of trust, chemistry, and rapport. It softens the edges of any criticism made on the inappropriateness of a lady clown. Gleaning from the clown–auguste pairing, many married couples built their acts around mutual (and matrimonial) agitation. One English couple, Albert Victor (1889–1948) and Louise (née Craston) Adams (1900–after 1978), appeared as Lulu and Albertino. Her mother had been a circus rider in the Belgian circus, who made political jokes and sang comic songs. Lulu, however, maintained that she was a “lady jester” and not a clown.Footnote 65 Her father, a clown, had formed her and her two siblings into a juvenile act called the Crastonians, which she left when she married. Her first “engagement as a clowness” was at the Paris Olympia in a troupe of twenty. When she and Albertino developed as a duo, at first they were a self-described “clown-and-the-lady-act.”Footnote 66 She performed alongside Albertino, playing a variety of instruments, including the bagpipes, and only eventually donned the clown's makeup alongside him.

They were transferred to the United States by Barnum & Bailey.Footnote 67 When the big show prepared to reopen at Madison Square Garden in 1939, the idea of a female clown was prominent in all the advance publicity. The New York Herald Tribune cited her as the first such performer in the world,Footnote 68 while the Hartford Courant began its article publicizing Adams's appearance with the question, “Ever hear of a lady clown? Lulu Albertino never did either.”Footnote 69 Ten years later, her uniqueness was still on display. In 1948, Judith Crist reported that “despite the plethora of clowns disguised as mammies, fat women, and ‘careening dowagers’ in the Ringling Brothers & Bailey Circus, there is only one real woman among the hundred funny men at Madison Square Garden.”Footnote 70 Crist was simply repeating Lulu's billing, prominent in the advertising for Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey's Circus that year.Footnote 71 The ratio, one hundred to one, seems to be applicable industrywide. Similar assertions were made in multiple publications.

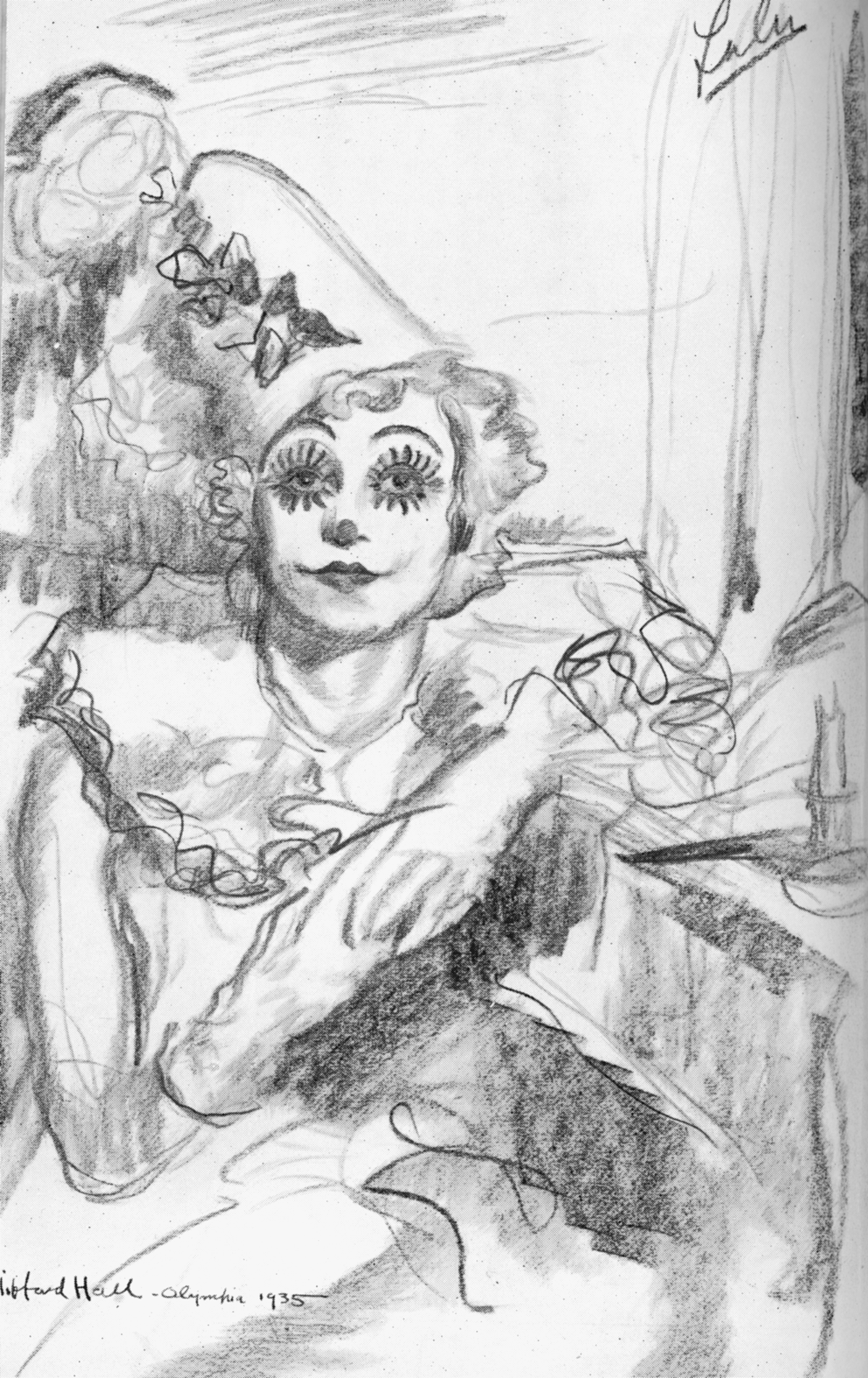

According to press agent Roland Butler, in Europe the rather plain, bespectacled Mrs. Adams performed with a showgirl look: a poodle cut, long eyelashes, and a Cupid's-bow mouth. This did not fit Ringling Brothers’ notion of the Joey, and so she received the white greasepaint, croquet-hoop eyebrows, and red heart for a nose, remodeling her as a “lady clown” of “beruffled femininity.”Footnote 72 Butler's claim was so much hoopla. Lulu Adams was, in fact, like all clowns, the inventor of her own “charmingly feminine clown makeup,” in a platinum blonde wig with tight curls and a red daub on the end of her nose and ears, black question-mark brows, and tear drops on her lower lids.Footnote 73 Her costume consisted of the standard conical hat, an organdy ruff, and a satin suit with Turkish trousers, liberally adorned with sequins, spangles, and rhinestones (Fig. 4).Footnote 74 This was very much in the tradition of the elegant white clown. Later, when she adopted the role of auguste, she transformed into the carroty-haired, red-nosed Bozo.Footnote 75

Figure 4. Lulu Adams by Clifford Hall, 1935. The Laurence Senelick Collection.

Equally spurious was Lulu's declaration that becoming a lady clown was all her husband's idea. “My husband felt that if women could be doctors and lawyers and dentists, there was no reason why they couldn't also be clowns.”Footnote 76 Besides its inaccuracy, for she had been clowning from girlhood, it tries to unite the pseudofeminist idea that all professions are proper for women with the antifeminist claim that her husband inspired her. Unlike La Pearl, Lulu Adams was conventional in insisting that to perform violence in her act would be inappropriate. “You know, one clown says to another, ‘You're a fool’ and smacks him on the head and the children roar, but you can't do that to a woman.”Footnote 77 Therefore, her clowning depended on props, musical instruments, and gags instead. She insisted that “a lady ought to be dignified . . . it's all to the good, because you don't want children to see violence and aggression, just good clean fun.”Footnote 78 In their usual routine, Albertino would pull an inexhaustible supply of whistles, horns, and other noisemakers out of his costume. As soon as Lulu would confiscate one device, Albertino would pull out another, and continue to make a ruckus. When Lulu would ask the children in the audience if Albertino had any more whistles, “sure enough, they'd be on Albertino's side—taking the rise out of me.”Footnote 79 She chewed a good deal of bubble gum in the act, wore gloves and a stocking that could stretch forty feet down the track, and rarely spoke.

The kind of double act represented by Loulou and Atoff could thrive in the one-ring, indoor circus found in European capitals. Anglo-American circuses, however, preferred the solo act with a preference for the talking clown (William Wallett, Dan Rice) and, later, the auguste (Lou Jacobs, Felix Adler, Emmett Kelly). With the metastasis of the North American circus into three rings, clowns proliferated into brigades, playing mass scenarios or serving as filler during scene changes. The clown dressing room was all-male, a stag atmosphere not unlike a locker room and unsympathetic to the kind of elfin whimsy practiced by Miss Loulou. In an English single ring, Lulu Adams and Albertino could patter, throw eggs around, play football (i.e., soccer) with the audience; but the massive size of the American circus kept their act at a distance.Footnote 80

Asked if she minded being made a laughingstock, Adams responded, “Not a bit. I think it's a very good idea, because, with this makeup, no one will ever know how old I am.”Footnote 81 The hoary libel of a woman's vanity is heard even here, but that was part of the joke. The clown is a role, and the real Lulu Adams is concealed by the makeup. Yet reporters and commentators failed to separate the performer (in this case, the woman) from the act. Furthermore, the subtext of her quip refers to frequent prejudices against female performers. She jests it is more humiliating to be an aging woman in show business than it is to be a clown. Being the butt of the joke, in an ironic sense, preserved her integrity.

In most of these marital duos, the husband predeceased the wife, and the breakup of the act forced a choice of carrying on or retiring. Albertino died of a heart attack in 1948 at the microphone in a radio studio; an hour later Lulu was at the dress rehearsal in Madison Square Garden.Footnote 82 She provides one example of a woman who felt wedded to her craft in the absence of her husband. Four years later she confided to a journalist that she and the practice were inseparable: “I was born into the circus. . . . I shall go on clowning till I die. That's the power of the circus, you can never leave it.”Footnote 83

Annie Fratellini (1932–97) was the most prominent clowness of her time. The sole female performer in one of the most famous clown dynasties of the twentieth century, for a while she resisted the family business, owing to her father who routinely told her he did not believe a woman could be a clown.Footnote 84 When she did enter she was then told she was too pretty to be a clown. She eventually paired with her husband, the comedian Pierre Étaix, and, unlike most of the women who came before her, went on as an auguste (he addressed her as “Fratellini,” and she called him “Monsieur”). Their act, lasting seven or eight minutes, began by building on earlier prop comedy, editing, and innovating. There were challenges to the arrangement, which Fratellini acknowledged. “If we have an argument before going into the ring,” she comments in an interview, “I don't feel at home in my skin. If he pretends to put my head on his shoulder when I know that he doesn't want to, it's awful. To be a wife and husband without playing a game and being in the ring is very difficult. And sometimes, Pierre doesn't understand this. He thinks I am different in life.”Footnote 85

Tristan Rémy's claim, made in the 1940s, that women were unsuited to play the auguste no longer holds up (if it ever did). Annie Fratellini incarnated that role quite successfully. Nevertheless, she felt it necessary to use her outfit to occlude her femininity and shield her clowning from such associations. The auguste's makeup and baggy clothes enabled her to conceal her gender more successfully than the white clown's getup might. Like La Pearl and Spiessert, she masked her femininity with a genderless costume: a red wig like her Uncle Albert's, a bowler hat, large shoes, and a few dots of black makeup. In her words, she had “to make the woman disappear while she summons up the clown.”Footnote 86 This did not mean that she had to conceal her female nature in order to play the traditionally masculine role. Her view was that the clown is fundamentally asexual, an abstract human being, not necessarily bound by the laws of the material world. Costume and makeup assist this metamorphosis. Any perception of the real individual underneath would, in her mind, disrupt the poetics of the clown.Footnote 87

In the act, her job as the auguste is to disrupt handsome, charming Étaix from whatever he is doing and aggravate him:

For instance, he is trying to do a sleight-of-hand trick: I show up, I do another one and mock him. He starts a second one: I show up again and I pour water into his hat; this disturbs him even more. My first three interventions are intended, each one, to demolish what he is trying to build. The clown actually does things, while I don't really do anything, but he puts up with me all the same.Footnote 88

As the act proceeds, the two comics gradually come together. In the musical episode, with two concertinas, they try to harmonize. The act ends with dialogue. “I weep because he makes me fall; he comforts me. I also try to get the spectators to comfort me . . . the character wants to be coddled some more.”Footnote 89 Lulu Adams's white clown had had a maternal quality, distributing candy to her juvenile audience. The childlike nature of Fratellini's auguste, mischievous but sensitive, acts as a surrogate for her conspicuous femininity. Fratellini admitted that her auguste was “the exteriorization” of herself; she had not learned from children, but claimed to enjoy a permanent childhood, a blend of mischief and naïveté. After Étaix's death, her daughter Valérie served as white clown to her mother's auguste. Such a clown duo, Fratellini claimed, had never before been seen in the circus.Footnote 90

Toward a Feminist Clown

The early pioneers may not have reinvented the clown, but they did revamp it (as many clowns do) with their own personality, physicality, style, and perspective. More important, they subverted assumptions regarding the comic body by infiltrating an archetype that was historically male. Even when they concealed their gender, and the audience did not recognize them as women, they still managed to supersede prevailing prejudices by proving they could clown in a way that matched their male colleagues. To be a woman clown now means finding aspects of female behavior that have been overlooked or neglected by their male precursors. Some have chosen to create innovation out of feminine experience and an explicit feminist agenda. For example, Gardi Hutter, often the only woman in a company of men, confutes traditional standards of femininity, sometimes as a witch or a malicious secretary. In her one-woman show, Joan of Arpo (2005), she plays the washerwoman Hanna, a stupid, ugly, toil-worn sort, with rude manners and crude mannerisms. Hanna battles an unwieldy pile of laundry as if she were Don Quixote trying to be Joan of Arc. Hutter notes that every clown, male or female, has to be original and tell his or her own stories.Footnote 91

Similarly, the contemporary Brazilian clown Karla Concá, known as Indiana, insists that there are feelings, ideas, and areas of comedy that men cannot readily invoke:

Women are different from men, and in humor too. Men's gags are completely different from women's gags. Women cry, scream . . . the male gagsters slap their asses, are more violent and not part of our universe. Women have a different logic about life, we give birth, we menstruate . . . and men have no idea what it is, only we feel it, so it is clear that our clowns will talk about this universe with much more ownership than the ones men [have].Footnote 92

Recently, such figures as Ana Luisa Cardoso, Rhena de Faria (Mlle Blanche), Adelvane Néia, Janie Follet, Silvia Leblon, Joan Mankin, Lilian Moraes (Currupita), Pepa Plana, the quartet “As Marias da Graça” (“The Marias of Grace”), and others too numerous (and too humorous) to mention have been mining this rich seam. They demonstrate that the funny, grotesque, silly, and maladroit are not at all at odds with being a woman. In some cases, they find new opportunities for comedy within the female body “without being masculine and also discovering and revealing its comicality without worrying about its cultural obligation of seduction and eroticism.”Footnote 93 Preexisting stereotypes and social rituals can be reinterpreted from a female viewpoint: Peggy Williams devised clown versions of Wagner's Brünnhilde (Fig. 5) and Mae West. The Brazilian theatre group Asfalto de Poesia organized a mock wedding ceremony in which women from the audience could “marry themselves.”Footnote 94 Ultimately, women continue to enlarge the idea of what a clown is. The adjectives “lady,” “woman,” and “girl” may be discarded along with the feminine endings. The clowness is now simply a clown.

Figure 5. Peggy Williams as Brünnhilde. The Laurence Senelick Collection.

Matthew McMahan is Assistant Director of the Center for Comedic Arts at Emerson College. He is the author of Border–Crossing and Comedy at the Théâtre Italien, 1716–1723 (Palgrave Macmillan) and has published research on vaudeville, clowning, jazz, and French farce in Nineteenth Century Theatre & Film, Theatre History Studies, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, New England Theatre Journal, Texas Theatre Journal, and HowlRound. His 2020 article on two Parisian clowns, Foottit and Chocolat, was awarded an honorable mention for the Robert A. Schanke Research Award at the Mid–America Theatre Conference..

Laurence Senelick is Fletcher Professor of Oratory Emeritus at Tufts University. He is the author or editor of more than twenty-five books, the most recent being Jacques Offenbach and the Making of Modern Culture (Cambridge University Press) and The Final Curtain: The Art of Dying on Stage (Anthem Press). Other publications include Soviet Theatre: A Documentary History; Stanislavsky: A Life in Letters; The American Stage: Writing on the American Theatre; A Historical Dictionary of Russian Theatre, The Chekhov Theatre: A Century of the Plays in Performance and The Changing Room: Sex, Drag, and Theatre, as well as more than a hundred articles in learned journals. Prof. Senelick was named Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2011) and a Distinguished Scholar by both the American Society of Theatre Research and the Faculty Research Awards Council of Tufts University.