The steady increase of the role that the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) plays in Russian politics has been one of the most pronounced trends of Russian political development over the last several years. Scholars must understand whether this tendency can be explained by the situational changes in the political circumstances after Vladimir Putin’s reelection in 2012 or rather by fundamental shifts in Russian society. Polls show an increase in the percentage of Orthodox people in Russia: the majority of the population (68%) claims to belong to the ROC (FOM 2014).

Previous research reveals the interconnection between the ROC, regional political culture, and political behavior. For instance, Roman Lunkin (Reference Lunkin2008), measuring Orthodox religiosity as a share of Orthodox communities in all Christian communities in the predominantly Russian-populated regions, concludes that the most Orthodox regions (primarily those in the Chernozem region and Southern Russia) voted for United Russia and national patriots in the parliamentary elections of 2003. In a comparative study of Russian political culture, Nikolai Kozlov (Reference Kozlov2008) argues that Orthodox moralism, which emphasizes the issues of faith and moral principles, is one of the most influential factors.

In this article, we utilize the concept of desecularization (Berger Reference Berger1999) as the main theoretical basis, which points to a worldwide revival of religions. Also, the main models of church-state relations, which can range from the ‘state church’ model to the disestablishment model, are referred to (Stoeckl Reference Stoeckl2018).

Our research puzzle relates to the nature of the pro-Kremlin authoritarian coalition. Traditionally, the explanation of political support for the party of power is reduced to the context of political machines (e.g., Hale Reference Hale2003; Golosov Reference Golosov2014; Tkacheva and Golosov Reference Tkacheva and Golosov2019) or to the study of ethnic republics (e.g., Goodnow, Moser, and Smith Reference Goodnow and Moser2012; White Reference White2016; White, Saikkonen Reference White and Saikkonen2017) but not other Russian (Russkie) regions. Surprisingly, the contribution of these regions to electoral support for the party of power and President Putin is almost completely ignored in scholarship. These regions are conservative, religious, and no less loyal. If one explores the top-25 list of the most loyalist regions during the 2018 presidential elections, one finds that besides ethnic regions (such as the Republic of Dagestan with 90.76% of votes for Putin or the Republic of Mordovia with 85.35%), it also contains such regions as the Tambov (81.81% of votes for Putin), Bryansk (81.6%), Kursk (81.01%), Penza (79.98%), or Belgorod (79.71%) oblasts. As a result, our focus is concentrated on the regional cluster and capturing the differences that exist among them. We endeavor to put this religious, conservative, and traditionalist Orthodox Belt on Russia’s political map. By doing so, our study can contribute to better understanding the political geography of Putin’s authoritarian regime.

In this work we aim to explore both individual and regional levels, assuming that the ROC regional structures may moderate individual preferences. Usually, a religiosity-voting nexus is explained on the individual level as religiosity is an individual trait and can be measured on the individual level (Kellstedt and Green Reference Kellstedt, Green, Leege and Kellstedt1993; Manza and Brooks Reference Manza and Brooks1997; Layman Reference Layman1997, 2010). Standard models of a religiosity-voting relationship assume that believers’ voting decision is explained either by variation between denominations or by the degree of individual religiosity with religious voters being more likely to support more conservative parties and candidates. By analyzing the subnational level, we will demonstrate that religion influences electoral behavior at the regional level: the higher the factor of Orthodox religiosity, the higher the factor of electoral support. This can be referred to as “desecularization from above” (Lisovskaya and Karpov Reference Lisovskaya and Karpov2010): the ROC is using its regional structures, access to national media, and connections with authorities to lobby its initiatives. We assume that some regions’ political religiosity—due to cultural legacy, economic and demographic structures, and the ROC’s activity—becomes an important factor of electoral behavior. Such regions are defined as Orthodox Belt regions due to higher levels of Orthodox religiosity, social conservatism, and traditionalist attitudes.

Our main research question can be formulated as follows: do citizens of the Orthodox Belt regions in Russia provide more electoral support to Putin and the “party of power”? Other researchers have already revealed the relationship between religiosity and loyalty in Russia (Kul’kova Reference Kul’kova2015), but the spatial dimension is often ignored. As we can see, it manifests itself in the emergence of a cluster, where patterns of political participation work differently. Thus, we aim to reveal the existence of a religious belt in Russia, which, on the one hand, shows higher levels of Orthodox religiosity, conservatism, and traditionalism and, on the other hand, electoral support for the Kremlin in national elections from 2011–2018.

We are primarily interested in the regional level, but since religiosity is a characteristic of an individual, we also consider that level of analysis as well. Our model is as follows: (1) we presume that Orthodox religious individuals are more loyal; (2) the link between Orthodox religiosity and pro-Kremlin voting is manifested in more religious regions. This effect is not widely distributed across the country, but it does have strong regional variations.

Our empirical strategy is threefold. First, we use regional-level data from the Atlas of Religions and Nationalities of Russia (ARENA) survey that is a representative survey conducted in 2012 with the main focus on religion and religiosity. Using exploratory factor analysis, we develop the index of Orthodox religiosity that allows us to (1) rank regions and (2) outline the Orthodox Belt. Then, we include this index into the panel regression models and test hypotheses on the effect of Orthodox religiosity on pro-Kremlin voting. Surprisingly, the Orthodox Belt almost entirely coincides with the former Red Belt regions. Second, we use individual-level data from the recent regional survey (38 regions) that is based on the World Values Survey (WVS) questionnaire. Using logistic regression analysis, we test the hypotheses on (1) a higher level of Orthodox religiosity, (2) higher exposure to conservative, traditionalist values, and (3) higher support for United Russia in the previously outlined Orthodox Belt regions. Third, we explore the role of the ROC regional structures in administrative mobilization, conduct case studies, and explore two model regions of the Orthodox Belt: Tambov and Lipetsk.

The article proceeds as follows. In the first section, we provide a brief theoretical and historical overview of the relationship between religiosity and voting, focusing on the Russian case. In the second section, we present our empirical analysis of the ARENA survey on the regional level and outline the Orthodox Belt on Russia’s political map. In the third section, we use individual-level data from the recent WVS-style survey in 38 Russian regions and demonstrate that respondents from the Orthodox Belt regions tend to be more conservative, religious, traditionalist, and loyalist. The fourth section presents a case study of the two most Orthodox regions in Central Russia: Tambov and Lipetsk. The final section contains our conclusions.

Orthodox Religiosity and Voting in Russia: Theoretical and Historical Perspectives

In this section we formulate our theoretical framework that brings together Orthodox religiosity, church-state relations, electoral behavior, and authoritarianism in Russia. The concept of desecularization (Berger Reference Berger1999; Karpov Reference Karpov2012; Shishkov Reference Shishkov2012) is used: it focuses on fundamental changes in state-church relations in postcommunist societies. We adjust it to the Russian authoritarian context and put emphasis on the role of the church structures (top-down movement) and regional variation of Orthodox religiosity and relationship to voting. In our opinion, emergence of the religious, conservative, and loyalist regional cluster may contribute to better understanding the stability of Putin’s political support base.

The impact of religion on political preferences is a well-discussed topic in social sciences, especially in the US context. The relationship between denomination, religiosity, and patterns of electoral behavior is a key issue for American political studies (Manza and Brooks Reference Manza and Brooks1997; Guth et al. Reference Guth, Kellstedt, Smidt and Green2006; Layman Reference Layman1997). Two main models of interaction between religion and politics are suggested: the ethnoreligious model and the theological restructuring model (McTague and Layman Reference McTague, Layman, Guth, Kellstedt and Smidt2009). The former one adopts Émile Durkheim’s view on religion, which considers it as a social-group phenomenon. Religious denomination is connected to other group factors like ethnicity, race, and region. The role of religious doctrine and rituals is understood as the maintenance of religious traditions and support for unique cultural norms among followers. As a result, internal cohesion among in-groups and differences between out-groups makes the instrumental use of religion by politicians possible. The latter model argues that the new religious gap is explained not by religious denomination but rather by beliefs and behavior. The gap encourages individuals to support traditionalist religious norms and participate in traditional religious rituals, thus manifesting their opposition to modernist values. The Russian case seems to be closer to the ethnoreligious model, as religious denomination is often associated with ethnicity in Russia.

The model example of the religiosity-voting nexus is the Bible Belt in the USA. The most religious US states are located close together in the south. The European tradition strongly differs from the US experience. From a historical perspective, the religiosity-voting nexus is considered a religious cleavage, which is a legacy of the Reformation. The introduction of universal suffrage in countries under the strong influence of the Roman Catholic Church led to the emergence of Catholic parties, which could rely on the mass support of populations (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Stein1967). As some studies reveal, denominational cleavage is stronger in Catholic and mixed countries in continental Europe than in predominantly Protestant UK and Denmark (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2004).

The state-church relations in postcommunist countries, with a legacy of state-sponsored atheist propaganda, can be considered as a special case. Some studies show that in the aftermath of the collapse of the USSR, religion became one of the pillars of national identity in many Central and Eastern European countries, despite having an atheist legacy (Pew Research Center 2017). Russia seems to be an underexplored case, with very few empirical studies on the effect of religion on political behavior, especially those focusing on regional variation. This paper aims to fill this gap by using new data on Orthodox religiosity—both on a regional and individual level.

Applying the Desecularization Theory to Postcommunist Russia

Researchers of church-state relations, describing the metamorphoses that took place in the ROC after the collapse of the Soviet Union, usually use Peter Berger’s desecularization theory. One of the most important points in this concept is the countersecularization process (Berger Reference Berger1999; Karpov Reference Karpov2012; Shishkov Reference Shishkov2012). This process implies a rapprochement between previously secularized institutions and religious norms, the revival of religious beliefs and practices, “the return of religion to the public sphere” (Lisovskaya and Karpov Reference Lisovskaya and Karpov2010, 278). This condition can be found in Russia with its reaction to forced secularization during the Soviet era. Researchers define the Russian case as desecularization from above, since the level of religious participation is low. And grassroots activists and NGOs are rather weak, but religious elites are relatively strong and have good connections with the authorities (Lisovskaya and Karpov Reference Lisovskaya and Karpov2010). This approach prioritizes the role of top-down desecularization and thus formal church structures, which may use state resources for promoting their agenda. We use this concept to bring together the ROC, state authorities, and believers: the state needs loyal voters, the church structures are interested in state resources, and believers follow the instructions from the clergy. According to Kristina Stoeckl’s (Reference Stoeckl2018) classification of church-state relations, Russia is close to the selective cooperation model, which is between the state church and laïcité models. The hierarchs of the church demanded an increase in the political or even legal status of the ROC. It can be argued that at some point, the ROC was close to the actual status of a state religion.

How can ROC and the Orthodox denomination affect the electoral behavior of voters? Standard models of the religiosity-voting relationship assume that believers’ voting decision is explained either by variation between denominations or by the degree of individual religiosity, with religious voters being likely to support more conservative parties and candidates. In this article, we add the regional level to the model, arguing that the ROC regional structures may moderate individual preferences. As it was mentioned, the model of desecularization from above stresses the efforts made by church authorities and neglects initiatives from below (Lisovskaya and Karpov Reference Lisovskaya and Karpov2010). Therefore, we assume that regional church activities may shape individual preferences of believers in a desired way. One can argue that Orthodox believers may support the UR (United Russia) party either due to its conservative agenda or due to their political loyalism, as UR is the party of power that is strongly associated with government and President Putin. Although UR may be considered as a moderate right-wing party that is responsible for numerous conservative initiatives since 2012, we argue that the latter explanation may be more relevant.

The political market theory, where voters may choose parties and their programs based on their individual preferences, is unlikely to work in the Russian authoritarian context. In fact, believers cannot choose between an Orthodox conservative party and a secular right-wing party. The only option that is offered (or even imposed) to religious, conservative voters is to manifest their loyalty by voting for the Kremlin. The ROC structures seem to be directly or indirectly involved in administrative mobilization, and they do not sell the believers’ votes to the best buyer. The only possible buyer of believers’ votes is the Kremlin, and the ROC is happy to show its usefulness. However, we do not argue that UR’s conservative agenda does not matter for religious voters; we stress the assumption that manifestation of loyalty to the Kremlin plays a more important role in our explanation of the religiosity-voting relationship in Russia.

The authoritarian context of Russian elections does matter. The alliance between the ROC and government is manifested in multiple cases of church-state cooperation on regional and local levels—events, programs, initiatives, NGOs, media projects, and more. Becoming a part of the regional administrative system implies being a part of the regional political machine (Frye, Reuter, and Szakonyi Reference Frye, Reuter and Szakonyi2014; Gilev Reference Gilev2017). Desecularization from above has enabled various Orthodox and conservative groups in Russian society, especially since 2012. The traditionalist agenda became an important source of higher levels of political loyalism in predominantly Russian, Orthodox, and rural regions, thus making this another regional support base for the Kremlin. We argue that desecularization from above headed by the ROC empowered conservative Russian regions by increasing their role in Russian electoral politics. If this process continues further, it might lead to a moving away from the selective cooperation model and drawing closer to the state-church model (Stoeckl Reference Stoeckl2018), at least within this regional cluster.

The ROC in the Russian Electoral Context

How can one summarize the history of state-church relations and the role of the ROC in national electoral campaigns in post-Soviet Russia? Although the church-state cleavage in the 20th century, and then a revival of religion in the aftermath of the collapse of the USSR, has not led to the rise of religious parties, the ROC and the Kremlin have a strong relationship. Since 1991, the Russian elite has considered the ROC a powerful actor in the political sphere. For instance, Russian patriarch Alexy II was given priority to speak first during the inauguration ceremony of President Boris Yeltsin on July 10, 1991. After the 1993 constitutional crisis, the ROC accepted the friendship of the government, thus exchanging its autonomy (and right to criticize the Kremlin) for financial support and political patronage (Mitrokhin Reference Mitrokhin2003). The initial period of a cordial friendship between the ROC and the state peaked in 1997–1998 with the adoption of the new Law on Freedom of Conscience, which de jure claimed the special status of the ROC. As Nikolai Mitrokhin (Reference Mitrokhin2003) argues, the ROC’s initiatives enjoy financial support from the government at all levels: from local to the federal government. The church projects often receive funding from local businessmen, which consider it as an investment in lobbyism or at least an advertising campaign. After the death of Alexy II and the enthronization of Patriarch Kirill in 2009, a new period in state-church relations began. At the very beginning of his tenure, Patriarch Kirill announced a new policy of the Orthodox Church’s active intervention into the so-called secular agenda. To support new activities, the ROC established new institutions, adopted new strategies, and launched various social and political campaigns. This trend accelerated after Putin’s return to the Kremlin in 2012. When President Putin announced the conservative turn, the ROC became one of the largest beneficiaries of this political decision. In other words, desecularization from above complemented authoritarian backsliding in Russia; and one of the outcomes is the emergence of the contemporary Orthodox Belt on the political map. Previous studies have shown the authorities’ desire to include the Orthodox elite in the political process not only at the federal level but also at the regional level (Ukhvatova Reference Ukhvatova2018). For instance, Orthodox clergy are a frequent participant of the governor’s inauguration. The rhetoric they reproduce reflects the calls of the authorities to strengthen spiritual and moral values in society, justification of the irremovability of power, and even the divine nature of political power (the key slogan is “All power from God”). In addition, the ROC’s priests show a mutual expressed interest in exerting their influence on the authorities. Thus, we expect that the factor of Orthodox religiosity will be reflected in the electoral results, where individual religiosity is moderated by church institutions at the regional level.

As the church may affect political behavior of believers, Russian politicians make attempts to instrumentally use religion in their electoral campaigns. A study of political party platforms from 1995 to 2005 explored the effect of the enhanced authority of Orthodoxy on ideological change in Russian society and revealed that Russian politicians refer to Orthodoxy as a symbol of Russian culture, patriotism, and national unity (Papkova Reference Papkova2006). Russian scholars also have found evidence of political rhetoric being used by clergy during worship in Orthodox churches. A recent study revealed the magnitude of Orthodox priests’ impact on the electoral preferences of parishioners: up to 18% of believers witnessed political statements from priests during the sermon (Bogachev and Sorvin Reference Bogachev and Sorvin2019). Moreover, 14.5% of the respondents relied on the recommendations of the priest in their electoral choice, one way or another. Half of them (7.4%) received recommendations during the sermon, and the other half (7.1%) personally asked the clergy for advice. Thus, the authors conclude that religion has a tangible impact on the political preferences of voters.

Another researcher from Russia also found evidence that in Moscow Orthodox communities, politics are quite often discussed (Kul’kova Reference Kul’kova2015). The clergy respondents admitted that parishioners often ask questions about politics. In addition to this, politics can manifest itself in sermons. For instance, during the 1995 and 1999 State Duma elections, sermons openly touched upon the inadmissibility of voting for communists. Besides, a priest can, in a veiled form, call on parishioners to vote, emphasizing how important it is to act in the current situation. However, the author does not claim that there is a definitive attitude toward political participation in all Orthodox communities.

The role of social conservatism has been revealed in many previous studies, and it is especially important given the fact the church is often seen as a highly conservative institution. There is an ongoing debate on the relationship between various elements of the social conservatism value system. Some scholars argue that moral traditionalism and authoritarianism are two distinctive value scales (De Koster and Van der Waal Reference De Koster and Van der Waal2007). Others note that the link between moral traditionalism and authoritarianism is not universal but varies across countries: in secular countries it is rather strong and in religious and traditionalist is much weaker (Pless, Tromp, and Houtman Reference Pless, Tromp and Houtman2020). We contribute to this debate by arguing that the authoritarian context matters: moral traditionalism and loyalism to authority may be enforced from above. Some argue that religious voters in Russia support those parties, which claim their commitment to traditional values and norms. For example, Maxim Bogachev (Reference Bogachev2016) has examined the relationship between the church and the political preferences of Orthodox believers. He found a positive, although weak, correlation between frequency of church attendance and electoral results of federal elections in 2003, 2007, and 2011, but causality was not proved. The support of the UR party was increasing from “Don’t attend” to “Once a month,” but was declining with higher frequency, from “Once a month” to “Once a week”; therefore, it is a nonlinear relationship.

These findings are consistent with previous research on Orthodox religion, regional political culture, and political behavior. For example, Lunkin (Reference Lunkin2008) explored regional Orthodoxy, which was measured as a share of Orthodox communities from all Christian communities in Russian regions (no less than 80% of ethnic Russians) and determined that the most Orthodox regions, primarily Central and Southern Russia, were likely to vote for the UR party and national patriots in the 2003 Duma election. These findings are consistent with earlier reports. In the 1990s, the most Orthodox regions were committed both to a pro-statist orientation (e.g., support for the preservation of the USSR on the referendum in March 1991) and a procommunist one (Lunkin Reference Lunkin2008). In his comparative study of the political culture in Russia, Kozlov (Reference Kozlov2008) reveals Orthodox moralism, which stresses the importance of faith and moral principles, as one the strongest factors affecting voters’ preferences. Orthodox moralism prevails in the black soil regions—Lipetsk, Tambov, Kursk, Bryansk, and Belgorod—and in the Volga region, Penza and Ulyanovsk.

Russia’s Electoral Geography

According to studies of elections in the 1990s, the key features of electoral geography in Russia boiled down to the distribution of voters according to the major ideologies of “democrats,” “communists,” “nationalists,” and “centrists,” which are relatively stable and change little from election to election (Titkov Reference Titkov and Rimskii2008). In addition, researchers identified more compact areas with stable types of political preferences. One of the examples is the formation of the Red Belt, the population of which is more likely to vote for the Communist Party of the Russian Federation in elections. Researchers referred to this phenomenon as the “effect of the 55th parallel” (Slider, Gimpel’son, and Chugrov Reference Slider, Gimpel’son and Chugrov1994, 718)—the voting of the reformist North of Russia against the conservative South. The differences in these areas were associated with the level of urbanization—the northern regions are more urban, which means they are more modernized and innovative, while the southern regions are more agrarian and conservative.

Previous studies of various types of voting that are characteristic of certain regions have highlighted the following. In the 1990s, researchers identified various characteristics: (1) a conformist type for the ethnic periphery, periphery, and semiperiphery in the Russian North, as well as partly for areas of new development in the east; (2) a leftist type in the rural periphery, as well as small and medium industrial centers in the south of Central Russia, the South Urals, and Western Siberia; and (3) a liberal type, which is more developed in Moscow and St. Petersburg, in cities with a population of over one million, and in the administrative centers of the northern part of the European part of Russia (Turovskiy Reference Turovskiy, Gel’man, Golosov and Meleshkina1999). Other researchers explain the difference in voting in various regions by the difference in political behavior of residents of different regions, features of the socioeconomic structure, history and nature of the development of the territory, ethnic composition of the population and geographical location, and the relationship termed “center-periphery” (Petrov and Titkov Reference Petrov, Titkov, Treivish and Artobolevskii2001, 231). As it was mentioned earlier, ethnic republics are often identified as a separate cluster with loyalist political preferences (Goodnow and Moser Reference Goodnow and Moser2012; Goodnow, Moser, and Smith Reference Goodnow, Moser and Smith2014; Saikkonen Reference Saikkonen2017; White Reference White2016).

The case of the USA and Europe illustrates that the religiosity-voting nexus is not equally dispersed across the country, but it is likely to be concentrated in several adjacent regions. The model example is the abovementioned Bible Belt in the USA. In this article, we aim to test the existence of a similar Orthodox Belt in Russia. One may assume that the area with higher Orthodox religiosity may have some specific traits. First, these regions may differ by some social and economic indicators, such as the share of the rural population, income, unemployment, and the percentage of ethnic Russians. It should be noted that these traits are featured in the discussion on applying to Russia the concept of political machine (Hale Reference Hale2003, Reference Hale, Kitschelt and Wilkinson2007; Golosov Reference Golosov2014). Second, regions may differ by value orientations. We assume that higher religiosity might be an element of a broader value system that emphasizes conservative, traditionalist norms (e.g., reproductive behavior), loyalty to authorities, and political conformism (Middendorp Reference Middendorp1991; Houtman Reference Houtman, Clark, Nichols and Lipset2001; De Koster and Van der Waal Reference De Koster and Van der Waal2007). Although religiosity is considered as an element of the social conservatism value system, one may argue that in the Russian political context after 2012 it plays an even more significant role. The conservative turn made the ROC the key actor in promoting a traditionalist, authoritarian, and loyalist agenda, thus making Orthodox religiosity almost a synonym of conservatism. This notion is consistent with previous research, which stresses the role of Russian political culture in explaining the patterns of pro-government voting (Kozlov Reference Kozlov2008).

Our study contributes to better understanding new trends in Russia’s electoral geography. We endeavor to outline a new regional cluster, the Orthodox Belt, that is characterized by higher levels of Orthodox religiosity, social conservatism (including moral traditionalism), and electoral support for the Kremlin in national elections.

The following hypotheses can be formulated:

H1: A higher regional level of Orthodox religiosity is associated with higher regional electoral support of the Kremlin in national elections in 2011–2018.

H2: Higher individual Orthodox religiosity is associated with higher levels of social conservatism attitudes.

H3: Higher individual Orthodox religiosity is associated with higher levels of political loyalty.

If these hypotheses are substantiated, we will be able to show that Orthodox religiosity is associated with political loyalty not only on an individual level but also on a regional level. Therefore, the significance of the relationship on the regional level may be interpreted as existence of the Orthodox Belt. The role of church and religion in Russian politics is growing, thus supporting the concept of desecularization from above.

Our empirical strategy is threefold. First, we test the effect of Orthodox religiosity on pro-Kremlin voting. Next, using panel regressions, we find the association between Orthodox religiosity and pro-Kremlin voting in the 2011–2016 national elections. Second, we use data from the “LCSR Regional Survey” for 38 regions and confirm our hypotheses on the individual level. Third, we explore the activities of regional ROC structures in two model regions of the Orthodox Belt—Lipetsk and Tambov. We find evidence of close church-state cooperation in many spheres and reveal the institutionalization of ROC structures, implying the inclusion of the ROC in regional political machines. These case studies aim to illustrate potential mechanisms of church-state cooperation in the political sphere.

Voting for the Party of Power between 2011 and 2018: The Emergence of an Orthodox Belt

Measuring Orthodox Religiosity in Russia

Russian scholars Sergey Filatov and Roman Lunkin (Reference Filatov and Lunkin2005) define the concept and term religiosity level as the number of practicing believers, meaning those who follow a particular faith and comply with prescribed religious practices. They note that the most convenient way of measuring the level of religiosity frequently used in Western studies consists of an answer to the following question: “Did you go to church last Sunday?” In the USA, 50% of respondents are likely to provide a positive answer to this question. This question is not asked in Russia because it receives only a small number of positive responses. Today, people in Russia are asked if they go to church once a month or more often; however, this question also receives a small number of positive replies, between 5% and 10%) (Filatov and Lunkin Reference Filatov and Lunkin2005).

In this article, the approach of Charles Glock (Reference Glock1962) is partially used, namely, the following measurements: (1) experiential (subjective emotional religious experience reflecting personal religiosity); (2) ritual (which includes, but is not limited to, church attendance); (3) ideological (adherence to the main provisions of the creed); (4) intellectual (including religious knowledge, which is often measured through practices such as reading religious literature, striving for knowledge of the laws of faith, its history, etc.); (5) ideological (adherence to the main provisions of the creed); and (6) integrative (this indicator claims to measure the effect of individual religiosity in other manifestations of a person’s life). This approach is the closest to the present study, since it includes a scale that measures the effect of individual religiosity in other manifestations of a person’s life. It allows including indicators that demonstrate the respondent’s attitude to the law, traditional values, readiness to participate in civic engagement, and more.

Project ARENA: The Measurement of Religiosity in Russia

To test the effect of Orthodox religiosity on pro-Kremlin voting, we assess regional levels of Orthodox religiosity, using the ARENA survey data. To our knowledge, it is the most detailed, regionally representative survey on religion and religiosity that has been conducted in Russia. However, we obtained access only to aggregate-level data; in this section we conduct only regional-level analysis. Using exploratory factor analysis, we assign religiosity scores to regions and then rank them, which allows us to outline the Orthodox Belt in Russia.

Project ARENA (Atlas of Religions and Nationalities of Russia) is the only recent study of religiosity in Russia that examines nearly all regions of the country. This study was conducted in 2012 by the research service ‘Sreda’. It made use of data collected through a country-wide survey that was representative of Russia and its 79 regions. The project was not conducted in the Chechen Republic, the Republic of Ingushetia, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, and Nenets Autonomous Okrug (ARENA 2012).

The primary goal of the project was to provide an overview of religious denominations and nationalities by considering the population and its geographical and administrative distribution. The project consists of approximately 50 questions about religion, attitudes to the state, and traditional values. Further analysis requires information about the numbers of Russian citizens who identify with the Orthodox Church and the importance of religion for the population of the country. The results of the survey are available only at the regional level; unfortunately, we have no access to individual data.

According to the survey, 41% of the population, on average, agrees with the following statement: “I am Orthodox and belong to the Russian Orthodox Church.” The highest share of positive responses (79%) comes from two regions: Tambov and Lipetsk Oblast. Nizhnii Novgorod Oblast and the Republic of Mordovia occupy second place with 69% of respondents agreeing with the statement. The Republic of Tyva has the lowest share (1%) as most of the local population are Buddhists. Among regions with a predominantly ethnic Russian population, the lowest number of Orthodox believers (22%) is found in Sakhalin Oblast.

The average share of respondents who identify with Islam is 4.7%. The Republic of Dagestan has the largest share of the Muslim population (83%). Dagestan is followed by Kabardino-Balkaria (55%), the Republic of Bashkortostan (39%), and the Republic of Tatarstan (34%).

Buddhism, Old Believers, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Judaism have the smallest numbers of followers amounting to less than 0.5% of the population. The Republic of Tyva has the largest share of Buddhists (62%). Tyva is followed by the Republics of Kalmykia (38%) and Buryatia (20%). As for the other abovementioned religions, they have a share of less than 1% of the population in several regions of the Russian Federation.

Even though a significant portion of the population identifies with different religious denominations, religion itself is not that important in the daily life of Russian citizens. On average, only 15% of respondents agree with the following statement: “Religion is important in my life” (for people identifying with different religions). In the Republic of Dagestan, 56% of the population gave a positive response to this statement. Dagestan is followed by the Republic of Bashkortostan (23%), Tambov Oblast (24%), the Republic of Kalmykia (23%), and Orel Oblast (22%). Religion is least important for those living in Khabarovsk Krai (5%), the Republic of Yakutia (6%), Novosibirsk Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, and Kamchatka Krai (7% in the last three regions). The significance of religion is comparable with beliefs in omens and superstitions. Of the respondents, 13% agreed with the following statement: “I believe in omens, fortune-telling, and fate.” The population of Kaliningrad Oblast has the largest share of those who believe in omens (25%). Kaliningrad is followed by Amursk Oblast, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (both have 24%), and Bryansk Oblast (23%).

Identifying the Most Orthodox Regions: Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of questions on religion and religiosity was employed to identify issues that were of utmost importance for the study. As we use aggregated data, the analysis was conducted on the regional level. Unfortunately, we had no access to individual data. We selected the issues that were related to Orthodoxy, attitude to religion, religiosity, and traditional values. Our goal was to make a distinction between various dimensions of religiosity as they may play different roles in political mobilization.

Let us consider in more detail the issues that are included in factor analysis and correlate the chosen approach of Glock with them (the percentage in each region that agree with the statement):

-

1) Experiential (subjective emotional religious experience reflecting personal religiosity):

-

– I am Orthodox and belong to the Russian Orthodox Church

-

– Religion plays an important role in my life

-

– I believe in God (a higher power), but do not follow any particular religion

-

– I encountered miracles and / or unexplainable phenomena

-

2) Ritual (which includes, but is not limited to, church attendance):

-

– I pray every day using prayers or my own words

-

– If possible, I follow all religious laws prescribed by my religion

-

– I confess once a month or more often

-

3) Ideological (adherence to the main provisions of the creed):

-

– I am ready to sacrifice

-

– I support traditional family foundations when a man is the head of the family

-

– I would like to have many children

-

– I help other people without asking anything in return and do charity work

-

4) Intellectual (includes religious knowledge, which is often measured through practices such as reading religious literature, striving for knowledge of the laws of faith, its history, etc.):

-

– I have read the gospel

-

5) Integrative (this indicator claims to measure the effect of individual religiosity in other manifestations of a person’s life):

-

– I am ready to participate in civil, voluntary, social work.

Seven predominantly Muslim regions were excluded from the sample to avoid the mixing of Orthodox and Islamic religiosity. The sample contained only predominantly Orthodox regions.

The results of the factor analysis of the most important questions are presented below (Table 1). We extracted two factors. Coefficients that had values of approximately 0.500 and higher were considered significant. Factor scores were saved as regression coefficients, which then allowed us to rank regions by religiosity factors. Factor 1 varies from -1.956 to 3.086 (the top five regions are the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Kaluga Oblast, the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Oblast, Bryansk, and Novgorod Oblast), and Factor 2 varies from -1.448 to 2.607 (the top five regions are the Republic of North Ossetia, and Tambov, Lipetsk, Penza, and Nizhnii Novgorod Oblast). Both factors are standardized variables (the mean is 0 and the standard deviation is 1). In each case, low and high values indicate low and high levels of religiosity on the regional level. The factor analysis produces a slightly different result than just selecting regions by the share of Orthodox believers. In the latter case, the list would contain such regions as Tambov (78%), Lipetsk (71%), Kursk (69%), Nizhnii Novgorod (69%), and the Republic of Mordovia (69%); therefore, these lists overlap but do not match. However, self-reported religious identification cannot be interpreted as a marker of religiosity (Filatov and Lunkin Reference Filatov and Lunkin2005); only a more complex indicator may capture various elements of religious attitudes and practices. In our opinion, EFA allows us to account for nuanced aspects of religiosity, thus making extracted factors more precise instruments for further analysis.

Table 1. Exploratory Factor Analysis, ARENA Survey (Regional Level)

Source: ARENA (2012). Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

We describe the resulting factors, regional-level scales, in the following way.

Factor 1: Conservative activism characterizes regions where believers prioritize ideological, intellectual and integrative dimensions of religiosity (community service, charity, volunteer work, traditional values) over rituals and Orthodoxy. The latter has a smaller significance for them.

Factor 2: Ritual belief characterizes regions where believers are mostly interested in rites associated with the Orthodox faith (experiential and ritual dimensions of religiosity), namely, adhering to religious doctrine, confessing, and praying.

How do we interpret these factors? Factor 1 places the main emphasis on the conservative agenda and activism, while Factor 2 stresses the importance of rituals and belonging to the ROC. One may argue that regions with a higher score for conservative activism may support the Kremlin more consciously, due to its conservative agenda, and regions with a higher score for ritual belief consider voting for the Kremlin as an expression of political loyalty.

Orthodox Religiosity and Pro-Kremlin Voting: A Regional Perspective

For further analysis, we used the following variables:

Putin: regional share of votes for Vladimir Putin in the presidential elections of 2012 and 2018.

UR (United Russia): regional share of votes for the United Russia party in the parliamentary elections of 2011 and 2016.

Orthodox: regional share of respondents who agreed with the following statement: “I am Orthodox and belong to the Russian Orthodox Church.”

Factor 1: factor score for Factor 1 (conservative activism) at the regional level

Factor 2: factor score for Factor 2 (ritual belief) at the regional level

Next, we examined correlations between these factors and voting results (Table 2).

Table 2. Correlation between Voting and Religiosity, 2011–2018 (Regional Level)

Source: ARENA (2012); Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation.

* p < .05

** p < .01

+ p < .1

The table of correlations between key indicators of voting and Orthodox religiosity demonstrates that Factor 2 (ritual belief) is more significant. Factor 1 (conservative activism) is not significant at all. Notably, this factor is negatively related to Orthodox faith. Therefore, we conclude that it is Factor 2, ritual belief, which may cause pro-Kremlin voting. We find a strong and positive correlation between “Orthodox” and Factor 2 (-0.883 [N = 72, p = 0.00]), while it is negative and nonsignificant for Factor 1: -0.077 (N = 72, p = 0.520). Such a strong correlation between Factor 2 and Orthodoxy shows that the key question “I am Orthodox and belong to the Russian Orthodox Church” is the most informative indicator of political religiosity; in fact, it encompasses belonging, rituals, and loyalty. Factor 1 (conservative activism) is excluded from our further analysis.

Factor analysis allowed us to identify the Orthodox Belt on Russia’s political map. In the Orthodox Belt, we include 15 regions that fall into the upper quantile of the Factor 2 ranking: the Lipetsk, Tambov, Belgorod, Kursk, Kostroma, Tula, Nizhnii Novgorod, Penza, Bryansk, Ryazan, Volgograd, Voronezh, Ulyanovsk, and Astrakhan Oblasts, and the Republic of North Ossetia–Alania. Most of these regions are located in Central Russia, and a few are in the Volga region and South Russia (see figure 1). With Factor 2 scores ranging from 2.607 (the highest value of political religiosity) to -1.448 (the lowest value), our selection includes regions with scores no less than 0.728; they all fall into the highest quantile of distribution.

Figure 1 The Orthodox Belt in Russia

We also created the following variables (at the regional level):

Income: average per capita income in 2011and 2016 (in rubles; Rosstat [2020] data)

Rural: share of the rural population in 2011 and 2016 (Rosstat [2020] data)

Russians: share of the ethnic Russian population (2010 census data [Rosstat 2010])

Unemployment: share of the unemployed population in 2011 and 2016 (Rosstat [2020] data)

To test our hypotheses on the relationship between religiosity and pro-Kremlin voting, we conducted panel regression analysis. We pooled electoral data for UR in 2011 and 2016 and for President Putin in 2012 and 2018; these are our dependent variables. Since our independent and control variables were both time-varying variables (Rural, Unemployment, and Income) and time-invariant ones (the ritual belief factor, Orthodoxy, and “Russians”), the pooling model was used (using a different estimation procedure—random effects—the same results were obtained; see tables S1 and S2 in appendix). Other options were less appropriate: the between estimator would reduce our sample, and fixed effect would exclude time-invariant variables due to collinearity. Our key independent variable was the ritual belief factor (the alternative was Orthodoxy). The key control variable was the share of ethnic Russians in the region: as Orthodoxy is often viewed not as religion but as a Russian-specific cultural trait, we wanted to account for ethnic structure. Typical socioeconomic variables were added as control variables. The results are presented in table 3. All calculations were conducted in R software, using the plm package.

Table 3. Voting and Religiosity in the 2011–2016 Duma Elections and in the 2012–2018 Presidential Elections in Russia

The regression analysis for supporting United Russia in the 2011–2016 Duma elections shows that the ritual belief factor is the key variable (using Orthodoxy as alternative independent variable yielded similar results; see tables S1 and S2 in appendix). The variable Russians has a significant negative effect in all models, and we interpret this as UR having higher electoral support in ethnic regions (mostly republics). These findings are consistent with current literature (Goodnow and Moser Reference Goodnow and Moser2012; Goodnow, Moser, and Smith Reference Goodnow, Moser and Smith2014; Saikkonen Reference Saikkonen2017; White Reference White2016). Notably, nearly all socioeconomic variables are significant except for Unemployment.

The model for pro-Putin voting demonstrates similar results. Again, Income and Rural are significant, and Unemployment is an insignificant predictor. The share of Russians is insignificant, which means that Putin’s support is more equally dispersed among all regions.

The results of the study demonstrate that there is a significant correlation between Orthodox religiosity and voting outcomes in 2011, 2012, 2016, and 2018 on the regional level. Religiosity operationalized as the ritual belief factor correlates positively with regional electoral support for the party of power in 2011 and 2016 as well as for the president in 2012 and 2018. Notably, Orthodox religiosity is not the same as Russianness. Although Orthodoxy is often seen as an ethnic religion of Russians (Filatov and Lunkin Reference Filatov and Lunkin2005, 42), we do not find a significant relationship between Orthodox religiosity and the share of Russians in the region. There is a negative relationship between voting and the share of ethnic Russians on the regional level.

To conclude this section, our regional-level analysis reveals the relationship between Orthodox religiosity and electoral loyalty. Therefore, our hypothesis (H1) was confirmed.

Measuring Values in the Orthodox Belt

Our previous findings were based on religiosity survey data from 2012. In this section, we confirm the existence of the Orthodox Belt in Russia. We accessed the recent “LCSR Regional Survey, 2019–2020” on subjective well-being in 38 Russian regions (Almakaeva, Andreenkova, Klimova, Soboleva and Ponarin Reference Almakaeva, Andreenkova, Klimova, Soboleva and Ponarin2019). The questionnaire included batteries on religion and religiosity, on attitude to reproductive and sexual behavior, on trust in political institutions, evaluating governor and mayor performance, support of political parties, and more. By using T-tests, as well as logistic and multilevel logistic regression analysis, we find that Orthodox Belt regions are associated with higher levels of religiosity, social conservatism, and political loyalty. The sample included five predominantly Muslim regions; and seven regions belong to the Orthodox Belt (Voronezh, Belgorod, Tambov, Tula, Volgograd, Nizhnii Novgorod, and Penza Oblast). We assumed that the Orthodox Belt regions would differ from regular Russian regions (non-Muslim) in their value orientations and political preferences.

First, we created a binary variable “OBelt,” which codes Orthodox Belt regions as “1,” others as “0,” and Muslim regions as “Missing.” As an alternative, scores for the ritual belief factor were used.

The survey includes three questions on religion and religiosity:

Apart from the fact of whether you attend religious services, can you say that you are: (1) a religious person, (2) nonreligious person, or (3) an atheist. We recoded this scale in the reverse way: (1) an atheist, (2) a nonreligious person, or (3) a religious person. The next step was to recode it into the dummy variable “Religiosity” with “1” as “A religious person” and “0” as “else.”

Apart from weddings, funerals, and baptisms, how often do you currently attend religious services? (1) more than once a week, (2) once a week, (3) once a month, (4) on special holidays, (5) once a year, (6) less than once a year, or (7) never. We recoded this variable in a reverse way: (1) never, (2) less than once a year, etc.

Do you practice any religion? We recoded this into the new binary variable Ortho, which codes “1” for Orthodoxy and “0” for any other religion. The next step was the creation of the dummy variable “Ortho Religious”: this is an interaction between “Ortho” and “Religiosity,” with “1” as “Orthodox religious person” and “0” as “Other”.

As an additional robustness check, we ran T-tests to test if the level of religiosity differs between Orthodox Belt regions and regular ones. The results show that Orthodox Belt respondents are more religious than respondents from other regions (see appendix, table S3).

The next series of T-tests compares Orthodox Belt respondents with regular regions’ respondents on their attitudes toward reproductive behavior, trust to political institutions and politicians, national pride, interest to politics, charity, and willingness to volunteer.

The battery on attitudes toward reproductive behavior includes three questions:

To what extent is homosexuality justifiable?

To what extent is abortion justifiable?

To what extent is divorce justifiable?

The ten-item scale is used where “1” means “Never justifiable” and “10” means “Always justifiable.” We recoded this variable in a reverse way.

The battery on attitudes toward politicians and trust in political institutions includes the following questions:

How would you estimate your regional governor’s performance?

How would you estimate your local mayor’s performance?

The four-item scale is used, where “1” means “Very good” and “4” means “Very bad.” We recoded this variable in a reverse way.

Do you trust the federal government?

Do you trust political parties?

Do you trust the State Duma?

Do you trust the president of Russia?

The four-item scale is used, where “1” means “Full trust” and “4” means “Don’t trust at all.” We recoded this variable in a reverse way.

The question about political preferences is as follows:

Which political party is the closest to your preferences?

We recoded responses into a binary variable “UR support,” where “1” is support for United Russia and “0” is for all other parties.

The final battery included questions on attitudes toward charity donations and willingness to volunteer:

Are you ready to donate to charity?

Are you ready to work as a volunteer for a social problem or a charity event?

A binary scale was used, where “1” is “Yes, I’m ready” and “2” is “No, I am not ready.” We recoded these variables in the reverse way: “0” is “No, I am not ready” and “1” is “Yes, I’m ready.”

We ran a series of two T-tests to check if the social conservatism attitudes differ both on individual level—between “Orthodox believers” and “else” (table 4)—and on the regional level—between Orthodox Belt regions and regular ones (table 5).

Table 4. T-Tests on Conservatism, Loyalty, Political Trust, and Political Activism: Orthodox Believers versus Others (Individual Level)

Source: LCSR Regional Survey. In this survey, “Yes” indicates an Orthodox religious person and “No” indicates other.

* p < .05

** p < .01

Table 5. T-Tests on Conservatism, Loyalty, Political Trust, and Political Activism: Orthodox Belt versus Regular Regions.

Source: LCSR Regional Survey. “Yes” is “belongs to Orthodox belt,” and “No” is “Does not belong.”

* p < .05

** p < .01

The results reveal a significant difference for almost all attitudes between both Orthodox believers and nonreligious persons and as well the Orthodox Belt and regular regions. The Orthodox religious respondents are significantly more conservative, traditionalist, and loyalist, with the exception of evaluation of regional governor and local mayor performance. They trust in political institutions and are likely to support UR.

The Orthodox Belt respondents are likely to be more conservative in their attitudes toward reproductive behavior; they are more loyal to regional and local authorities. They also are likely to be more trusting in the State Duma and the president; the difference in trust in political parties is marginal, and the difference in trust in the government is insignificant. The level of UR support in the Orthodox Belt regions is slightly higher than in other regions. However, they are less likely to work as a volunteer; and there is no significant difference in willingness to donate to charity.

Orthodox Religiosity and the Support of the United Russia: An Individual-Level Analysis

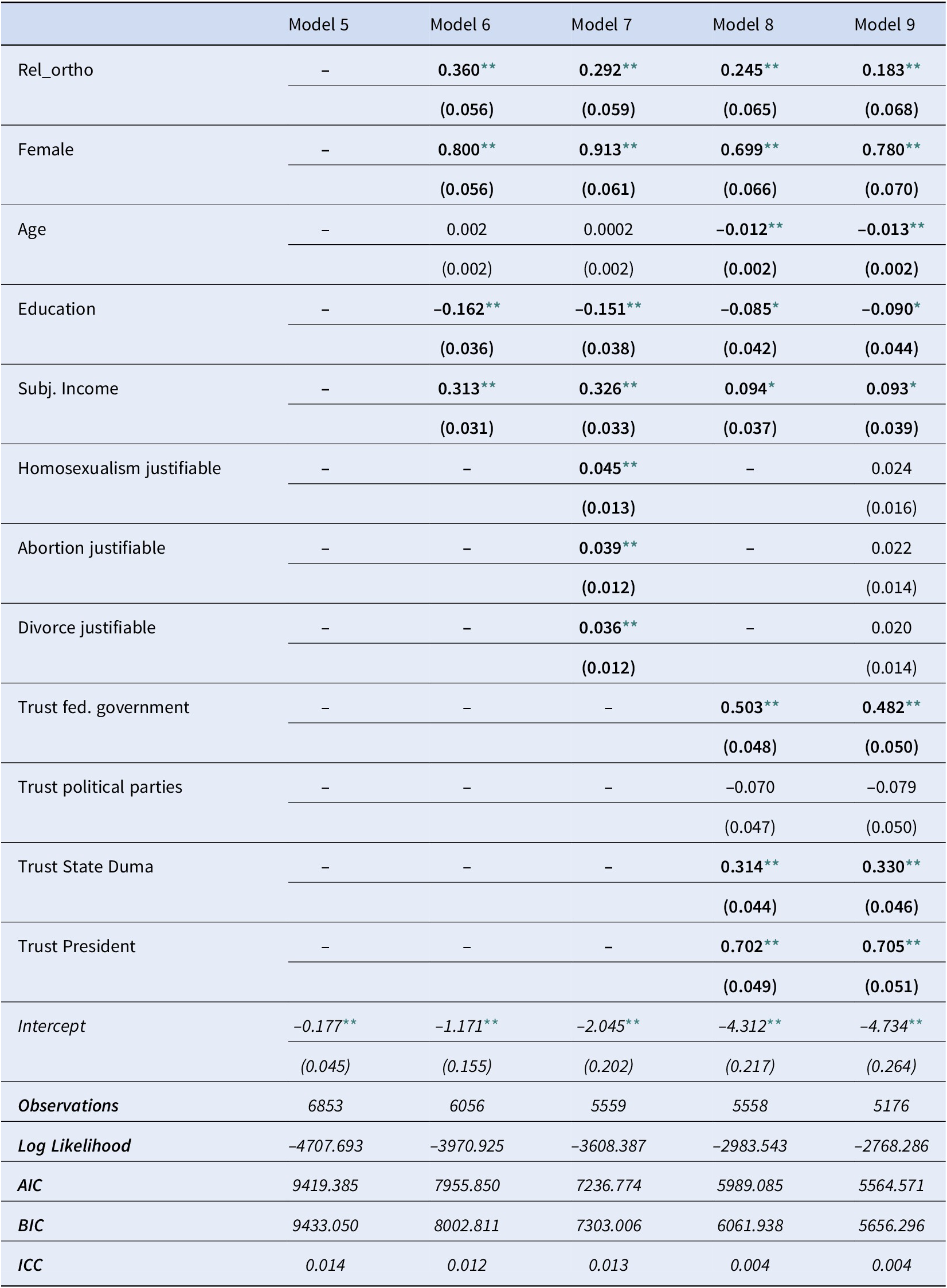

Our next step is testing the hypothesis on a higher level of support for the United Russia party in Orthodox Belt regions. We run logistic and multilevel logistic regressions using the binary variable “UR Support” as our dependent variable. The key independent variable is the “Orthodox religious” dummy. Our sociodemographic control variables are “Female” (recoded as “0” [male] and “1” [female]), Age (in years), “Education” (four-item scale: “1” is primary education or less and “4” is higher education or an academic degree), and “Subjective Income” (four-item scale and recoded: “1” is living in poor conditions, and “4” is no financial problems). We also include various social conservatism batteries to test if religious persons prefer United Russia due to traditionalism or loyalism: (1) justifiability of homosexuality, abortion, and divorce; (2) institutional trust in the federal government, political parties, the State Duma, and the president; and (3) both. First, we start with logistic regressions (table 6).

Table 6. Orthodox Belt and UR support in 2018: Logistic Regressions (Individual Level)

Note: Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors in parentheses.Source: LCSR Regional Survey. DV – UR support (dummy).

** p <.01

* p < .05

Our models show that Orthodox religiosity is positively associated with support of the United Russia party.

Among significant predictors, in all models we find Female (females have a higher chance to support UR), Subjective Income (the higher the income, the higher the chance to support UR), Education (the lower the education, the higher the chance to support UR), and (but only in Models 3 and 4) - Age (the lower the age, the higher the chance to support UR). The latter finding is counterintuitive as the support for United Russia is often associated with popularity of the party of power among older people, especially pensioners. Having no proper explanation, we may propose two potential mechanisms. First, it is socialization: the support of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) (perhaps due to Soviet nostalgia) among older respondents is still much higher than among young people. Second, it is more effective administrative mobilization of respondents of a younger age. They might have higher employment rates than older respondents, so they are more prone to administrative mobilization from their employers. In model 2, we add a battery on traditionalism and find that all variables remained significant. In model 3, we add a battery on institutional trust and find that all variables except trust in political parties are significant. Model 4 contains both batteries, traditionalism and loyalism. The results show a lower significance of traditionalist predictors, and it is the only one with insignificant Orthodox religiosity. To do robustness checks, we also ran some other models with additional predictors; they do not change our results (see table S4 in appendix).

Then we add the factor score for ritual belief that was created at the previous stage of our analysis as a second-level predictor and run a series of multilevel logistic regressions (table 7).

Table 7. Orthodox Belt and UR Support in 2018: Multilevel Logistic Regressions (Individual Level)

Note: Unstandardized coefficients and standard errors in parentheses. Grouping variable is the factor score “ritual believers.”

Source: LCSR Regional Survey 2019. DV – UR support (dummy).

** p < .01

* p < .05

Model 5 is an ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) model, with the ritual belief factor being included. Then we add sociodemographic predictors (model 6), a battery of traditionalist predictors (model 7), a battery of loyalist predictors (model 8), and both batteries together (model 9). All our models show that our key independent variable, Orthodox religiosity, is significant. Again, among significant predictors we find Female (females have a higher chance to support UR), Subjective Income (the higher the income, the higher the chance to support UR), Education (the lower the education, the higher the chance to support UR), and only in models 8 and 9 Age (the lower the age, the higher the chance to support UR). Models 7 and 8 show the significance of traditionalist and loyalist predictors, respectively; only trust to political parties is insignificant. But when batteries were included together in one model (model 9), all traditionalist predictors lose their significance, while nothing changes for the loyalist ones. We interpret this as a higher importance of loyalism for Orthodox religious respondents in explaining UR support. Interclass Coefficient Correlation (ICC) varies in our models from 1.4% in model 5 to 0.4% in 8 and 9. These finding reveal that not only individual but also aggregate Orthodox religiosity affects support for UR.

Therefore, hypotheses 2 and 3 were confirmed. The Orthodox Belt respondents are more religious, conservative, and loyal to authorities. Moreover, belonging to the Orthodox Belt increases the chance to support the United Russia party, with demographic controls.

How do contextual and individual religiosity complement each other in supporting electoral loyalty? Our next section presents two case studies that shed light on some potential mechanisms that may strengthen the association between the ROC and loyalty to authorities. Having demonstrated the importance of the regional level for explaining the relationship between religiosity and voting, we assume that this may be caused by certain institutional arrangements in church-state cooperation.

The Strongholds of Orthodox Loyalty: Lipetsk and Tambov

This section presents an overview of two regions belonging to the Orthodox Belt. The choice of regions was determined by their position at the top of the rankings in the Orthodox Belt regions; moreover, these regions have the highest shares of Orthodox believers according to the ARENA survey, and they have the highest ritual belief factor scores (other than the Republic of North Ossetia). As we assume that the emergence of the Orthodox Belt is at least partly the result of desecularization from above, we need to explore how the church-state alliance works on the ground. Our goal is to find similarities in the ROC regional structures’ strategies: how they build relations with regional authorities, promote a conservative agenda, and influence potential religious voters. First, we will demonstrate how regional electoral preferences were changing from support for communists to support for the party of power. Second, we will show how the political influence of the ROC in a particular region expanded. The ROC seeks to create institutional partnerships with local authorities and, consequently, increase the institutionalization of the church’s power, with healthcare, education, and mass media being among the core interests of the ROC (e.g., Kratochvil, and Shakhanova Reference Kratochvíl and Shakhanova2021). Some studies argue that Orthodox priests may influence believers’ electoral choice (Bogachev and Sorvin Reference Bogachev and Sorvin2019). Although our desk research analysis did not reveal smoking-gun evidence of the ROC priests’ involvement in the electoral campaign in these regions, we found enough facts showing the ROC structures being de facto elements of regional political machines. If the overall church-state cooperation model in Russia is usually defined as selective cooperation (Stoeckl Reference Stoeckl2018), the cases of Tambov and Lipetsk are much closer to the state religion model, where, on the one hand, the church enjoys multiple privileges and benefits, but on the other hand, as being de facto a part of the state it bears certain responsibilities, including participation in loyalist political mobilization.

Lipetsk

Lipetsk Oblast is a middle-income, agro-industrial region. The oblast is 22nd in the 2019 rating of the regional socioeconomic situation and 11th in the rating of the quality of life (RIA Rating Reference Rating2019). Between 1998 and 2018, Oleg Korolev served as the governor of the oblast. Korolev had been a part of the Lipetsk political elite since the beginning of the 1990s, as a deputy and chairman of the Local Council of People’s Deputies. Throughout the 1990s, he supported the Communist Party of Russia (CPR), and his support aided him in securing a victory in the 1998 gubernatorial election. Describing the regional political situation, Michael McFaul and Nikolai Petrov characterized the region as “a typical representative of the Black soil Center with the agro-industrial type of economy with a significant export of metal by the Novolipetsk Steel Mills enterprise; old party nomenclature elites that regained power in a year after 1991; and ‘red preferences’ of the electorate” (Reference McFaul and Petrov1998, 163). In the 1996 presidential election, Zyuganov overcame Yeltsin in both rounds of voting. In 2003, Korolev joined the United Russia party. In the 2003 Duma elections, the gap between United Russia and the CPR was not very wide (28.2% and 17.6%, respectively); however, the situation changed during the 2007 election. Voting for the party of power significantly increased: UR gained 62.30% of the vote, while Communists received only 13.03%. In 2011, electoral support somewhat decreased (40.3% for UR and 22.8% for the CPR), but in 2016 UR gained 56.19% votes and CPRF gained only 13.68%.

Korolev’s loyalty to the federal center was expressed not only through the achievement of impressive electoral outcomes but also through the strengthening of “spiritual staples” (duhovnye skrepy) in the region. Korolev received the order of Seraphim of Sarov and the medal “In Memory of the 100th Anniversary of Reinstatement of the Patriarchate in the Russian Orthodox Church” for his service to the church.

Lipetsk’s diocese has a vast influence in many areas of society. The diocese has signed partnership agreements with regional authorities, businesses, and NGOs. Agreements have been signed with the following organizations:

-

– Regional Department of Internal Affairs

-

– Regional Department of the Ministry of Justice

-

– Lipetsk State Institute for the Advancement of Teachers

-

– Regional Department of Penitentiary Service

-

– Department of Education and Science of Lipetsk Oblast

-

– Department of Healthcare of Lipetsk Oblast

-

– Department of Culture and Arts of Lipetsk Oblast

-

– Lipetsk Regional Union of Consumer Associations

-

– The regional newspaper Lipetsk Newspaper

-

– Regional Department of the Federal Service for State Registration

-

– The Council of Atamans of the Local Cossack Association in Lipetsk Oblast (Matvienko Reference Matvienko2015, 127–128)

The Diocese department of the Lipetsk archdiocese is highly involved in organizing various educational activities. Since 2000, there has been a partnership agreement between Lipetsk Oblast Department of Education and Science and the Diocese department. There are also agreements between several educational institutions and the ROC about the organization of optional classes for the course Foundations of Orthodox History. The Orthodox children’s center, called Revival, the main educational project realized by the Diocese department, became the winner of the national contest “Moral Feat of the Teacher” in 2007 (Pogorelova Reference Pogorelova2019). Among other projects, it is worth highlighting the following:

-

– “Week of orthodox culture in educational institutions” of the city of Lipetsk and the Lipetsk region. Of the region’s general educational institutions, 70% participate in this event every year.

-

– “Regional contest of literary and musical compositions ‘Hallowed Be Thy Name’” (since 2011). Around 40 creative teams from both secular and religious educational institutions of the city of Lipetsk and Lipetsk Oblast participate in this event on an annual basis.

-

– Regional theological youth readings of “Be as perfect as thy Heavenly Father” (since 2012).

-

– “Orthodox tent family settlement of John the Apostle” or “Patmos” in the village of Kon-Kolodez located in the Hlevensky District of Lipetsk Oblast (since 2009). This settlement is regularly attended by 200 children and adults (Pogorelova Reference Pogorelova2019).

The diocese also is expanding its influence in public healthcare. The Lipetsk Oblast Department of Healthcare has signed frequent partnership agreements with the Lipetsk Archdiocese of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate since 2003 (Health Information Portal of the Lipetsk Region 2018). According to the official website of the Healthcare Department, medical workers cooperate with priests when carrying out social and medical assistance. The Lipetsk diocese holds regular conferences and forums, with local and federal healthcare departments as co-organizers (e.g., Patriarchia.ru 2007). This partnership focuses on such issues as pregnancy termination, professional ethics of obstetrician-gynecologists (OB-GYN), and prevention of drug addiction and alcoholism, as well as the organization of psychological help for HIV patients. The oblast has established a society of Orthodox doctors chaired by Mikhail Korostin the chief medical officer of the Lipetsk Oblast Narcology Center.

The antiabortion movement is very active in Lipetsk Oblast. There are many pro-life rallies and flash mobs in the region (Gorod48.ru 2017). The local OB-GYN, Elena Ivakina, became the winner of the national contest “The Sanctity of Motherhood” (Gorod48.ru 2019a). She was praised for saving pregnancies of women who had applied for an abortion. For example, Boris Mikhailuk, the former physician of the district hospital who currently works as an editor-in-chief of the newspaper Orthodox Usman, visits medical organizations in the small city of Usman to talk with women who are planning an abortion (LipetskMedia.ru 2015). The oblast also has a regional office of the movement known as “Pro-life,” an NGO that focuses on increasing fertility rates.

The anti-alcohol movement is another visible and powerful movement in the region. In September of 2019, the march “For Sobriety!” was held in Lipetsk (Gorod48.ru 2019b). This event was organized by the Lipetsk Orthodox society Sobriety. The society has been active since 2014, and its leader works both as a psychiatrist-narcologist and a priest, simultaneously. Its activities include educational events in churches, schools, and vocational colleges. They talk about addiction and a sober lifestyle. Notably, five months after the “For Sobriety!” march, 39 bars in Lipetsk and 9 pubs in Yelets, the second biggest city in Lipetsk Oblast, were shut down.

Tambov

Tambov Oblast occupies the 52nd position in the 2019 rating of regional socioeconomic development and 43rd in the rating for the quality of life (RIA Rating Reference Rating2019). McFaul and Petrov described the political portrait of Tambov Oblast in the mid-1990s in the following way: “This is a full-fledged member of the black soil ‘red belt’ with communist preferences of the electorate, prevalence of communists in regional governments, and the local power of Soviets” (1998, 893). This region was characterized as a model example of an “undefeated red Vendée” that actively resisted democratic innovations coming from the federal center (897). Oleg Betin headed the administration of the region between 1999 and 2015. Later, he also became a member of United Russia. Similarly to Lipetsk Oblast, United Russia received a small advantage over the communist party in Tambov in the 2003 Duma election (28.9% vs. 20.5%). In the 2007 Duma election, the situation also changed. The electoral support for United Russia went up to 60%, while Communists gained only 19.7%. This trend continued in 2011 when UR received 66.7% and CPRF 16.5%. In 2016, United Russia gained 63.5% and CPRF 10.8%.

In 2001, the Russian Biographical Institute and the leadership of the ROC awarded Oleg Betin, a former supporter of the CPRF, with the title “The Best Governor of the Year” in the nomination for “Person of the Year.” Interestingly, his wife chairs the Tambov Oblast Public Fund for the Revival of Orthodox Shrines.

Oleg Betin is known for his conservative anti-homosexual statements. In a 2008 interview with the Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper, Betin claimed that homosexuality was “a perversion” that violates the “inviolability of the Orthodox principles” (Vorsobin Reference Vorsobin2008). After these comments were made, LGBT activists filed a complaint to the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation; however, it was rejected (Newsru.com 2008).

Just as the Tambov region was a model example of a Red Belt region, it also became a good model of restoring “spiritual staples.” The ROC is especially active in the public education sphere. Since 2012, new classes on religious culture have been introduced in all educational institutions of all Russian regions. In 2011, Tambov Oblast was used as a pilot region for this course.

The Tambov diocese is also actively involved in various educational activities. Since 1992, it issues Tambov Diocese News, a newspaper that later was transformed into a monthly magazine. Interestingly, the magazine published a series of articles on political and economic issues before the federal election campaign in the Church and Society section. These pieces include an article about the efficiency of an amoral economy published before the election of 2011 and an article titled “Patriotic heritage and some practical issues of human life, family, society, state,” published in February 2008 before the presidential election.

The diocese also signed several partnership agreements with regional authorities. A partnership agreement between the Tambov diocese and the Department of Healthcare in Tambov Oblast was signed in 2010. This partnership involves “organization of Orthodox summer camps, prayer rooms, identification of and care for street children in difficult life situations, social support of disabled people, families with many children, elderly, and low-income individuals, organization of joint informational and charitable events, seminars, and round tables” (SOVA 2011a).

The Tambov diocese is a key actor in the anti-abortion movement in the region. The diocese supported the #Pro-life campaign led by an organization with the same name. This organization suggested petitioning the president of Russia to ban abortions. To support this petition, the churches of Tambov Oblast started collecting signatures on their premises (Nazarova Reference Nazarova2017). Anti-abortion activism is not limited to the collection of signatures. In 2017, medical workers were proud that they saved 644 lives that year (Shurkhovetskaya Reference Shurkhovetskaya2017). According to local reports, the establishment of crisis centers in women’s clinics led to a 15% decrease in abortion rates.

In addition to the agreement with the Department of Healthcare, the diocese has an agreement with the Regional Department of Labor and Social Development (SOVA 2011b). In December 2019, the Tambov diocese of the ROC signed an agreement on cooperation and partnership with the regional branch of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Tambov Oblast (Upolnomochennyi 2019). This agreement implies cooperation with the purpose of protecting rights and freedoms, legitimate interests of a citizen and an individual, solving socially important and legal problems, and developing and strengthening spiritual and moral values that are traditionally Russian and common to humans. Additionally, the Tambov diocese has partnership agreements with the Commissioner for the Rights of Children, the regional branch of the Ministry of Emergency Situations, and the Department of National Guard of Russia in Tambov Oblast.

The Tambov diocese leadership announced several demands to the current governor, Alexander Nikitin. In 2017, Tambov’s metropolitan sent a letter to the governor containing a list (26 items) of buildings and other properties that the Russian Orthodox Church intended to reclaim (SOVA 2017). This list included three schools, lands of the Kazan Monastery, buildings of the Department of Finance of Tambov Oblast built on the territory of that monastery, four apartment blocks formerly owned by the Ascension Convent, a five-story building, and an unfinished restaurant located on the territory of the Transfiguration Cathedral (the metropolitan required that people living in the building be evicted). As a response to this letter, the administration of the region created a working group that was supposed to review the demands of the metropolitan. According to the governor’s deputy, Natalya Astafyeva, “cooperation between church and state” will help “make Tambov a better and more beautiful [place]” (Kalashnikov Reference Kalashnikov2017).

Tambov’s Orthodox clergy also introduced a creative approach to the organization of religious processions. On several occasions, the clergy carried out airplane processions using the Tupelov Tu-134 aircraft. The first airplane procession was organized in 2007 to celebrate the 325-year anniversary of the Tambov diocese and the 70-year anniversary of the Tambov Oblast (Tambovskaia metropolia, Reference metropolian.d.). In 2011, it was devoted to celebrating the victory in the Great Patriotic War.

These regional reviews demonstrate that regions of the Orthodox Belt are governed by conservative administrations that seek to impose new moral norms on local populations. The structure of the ROC plays an important role in the institutionalization of relations between local elites and the church. The main instruments include the signing of agreements between the ROC and regional authorities, the active involvement of the ROC in the decision-making process in healthcare, and education. Both cases show that desecularization occurs from above: regional administrations build partnerships with the ROC structures but not with church NGOs and activist groups. The promotion of a conservative, religious, and traditionalist agenda contributes to political support from authorities.

These findings assume that the population’s political loyalty—the religiosity-voting nexus—may be explained not only by individual religiosity but also by institutional changes. The institutionalization of the ROC structures may serve at least two purposes: facilitating conservative socialization and administrative mobilization of voters. In Russia’s authoritarian context, such a close cooperation with the state implies involvement in political mobilization (e.g., Bogachev and Sorvin Reference Bogachev and Sorvin2019). The ROC structures promote a conservative agenda, which includes not only traditionalism but political loyalty, which is to be manifested in pro-Kremlin voting.

Conclusion