Introduction

The international framework

Historically, community participation in health has occurred in nearly all communities (Rifkin, 1996) but increased in popularity after the Alma-Ata Declaration (World Health Organization, 1978). Subsequently, participation was viewed as a central part of the Primary Health Care (PHC)Footnote 1 approach, along with a focus on prevention and an intersectoral approach. The Alma-Ata Declaration emphasizes participation in ‘planning, organisation, operation and control of primary health care, making the fullest use of local, national, and other available resources; and to this end develops through appropriate education the ability of communities to participate’ (World Health Organization, 1978:2).

Community participation received renewed commitment with the signing of the Astana Declaration (World Health Organization, 2018) to mark the 40th anniversary of the Alma-Ata Declaration. Member states confirmed their commitments to the principles of the Alma-Ata Declaration, including participation in the ‘development and implementation of policies and plans that have an impact on health’ (World Health Organization, 2018: s VI).

Community participation has also become part of WHO’s discussions on creating people-centered health systems. It is an essential feature in WHO’s Framework on Integrated, People-Centered Health Services (World Health Organization, 2016), which frames social participation as a way of strengthening health governance. It states that ‘strengthening governance requires a participatory approach to policy formulation, decision-making and performance evaluation at all levels of the health system’ (ibid: 6). Participation is furthermore a cornerstone in a human rights framework.

The Right to Health is a central socioeconomic right stipulated in the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (UN General Assembly, 1976). The Right to HealthFootnote 2 is interpreted in General Comment 14 (UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, 2000), which positions participation as a central component to achieving this right. It defines participation as ‘decision-making’ that should occur at local, national, and international level (ibid: 14:3). Further, General Comment 14 specifies that participation entails being part of political decisions related to health (ibid: 14:5). General Comment 14, which South Africa ratified in 2015 and submitted its first report on in 2017 (UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, 2017), also outlines the importance of participation in the formulation of a national public health strategy and plan of action. Moreover, it emphasizes that member states have an obligation to put in place mechanisms for participation.

The Alma-Ata and the Astana Declarations, General Comment 14, and WHO’s Framework for Integrated, People-Centred Health Services (hereafter referred to as the international PHC and human rights framework or, in short, the international framework) thus defines participation as involvement in decision-making with regard to priority-setting, planning, implementation, and evaluation at local, national, and global levels. In other words, participation in health is about participation in health governance. Further, these documents highlight that participation should include input in policies. This paper conceptualizes meaningful participation in line with the international human rights framework as ‘a process where community members are part of the decision-making processes related to health governance. They are part of setting the agenda, identifying problems, planning, implementing solutions and have an oversight and accountability role. Their participation also entails influence on policy issues.’

Community participation as part of a PHC approach in South Africa

In South Africa, community participation became part of a wider ongoing health system reform post-apartheid, which aimed to move away from a centralized, mainly curative health system to establish a decentralized district health system. The notion of participation features prominently in the critical health policy of the post-apartheid government, the White Paper on Transformation of the Health System (hereafter the White Paper) (Department of Health, 1997), which describes active participation as essential to the PHC approach. The White Paper conceives participation as entailing community involvement in ‘various aspects of the planning and provision of health services’ (Department of Health, 1997: ss2.5.2 (a)). It also emphasizes the importance of establishing mechanisms to improve accountability and promote dialogue and feedback between the public and health care providers. Like General Comment 14, the White Paper emphasizes peoples’ participation in national policy and proposes national health, provincial, and district summits as mechanisms for public participation (ss2.5.3). In that sense, the White Paper presents participation consistent with General Comment 14 and the PHC framework. Finally, the White Paper views health committees as structures that are elected.

National legislation

Community participation in South Africa was subsequently formalized in the National Health Act 61 of 2003 (NHA) (Department of Health, 2004), with provisions for establishing health committees, hospital boards, and district health councils. The NHA stipulates that each clinic or community health center or a cluster of these should have a health committee. Health committees should be composed of one or more local government councillor(s), the head(s) of the health facility/facilities, and one or more community members in the area served by the health facility/facilities. Furthermore, the Act requires that the country’s nine provincial governments develop legislation that stipulates the role and functioning of health committees in their province. South Africa is one of three countries in South and East Africa with legislation on health committees (Loewenson, Rusike and Zulu, 2014).

Besides the NHA, there are several policy documents at national level relevant to community participation and health committees, reflecting different ways of conceptualizing health committee participation. In 2013, the National Department of Health issued a Draft Policy on Health Governance Structures (henceforth, the National Draft Policy) (Department of Health, 2013), which articulates a view of health committees consistent with the White Paper and the international frameworks. The National Draft Policy views health committees as governance structures concerned with planning, oversight, and accountability. The policy’s intention for community participation structures is a substantive one a) to involve communities in the various aspects of planning and provision of the health service within their local catchment areas; b) to establish mechanisms to improve public accountability and promote dialogue and feedback between the public and health providers, i.e., public hospitals, clinics and community health centres. To achieve these substantive intentions, the policy includes roles such as 1) assisting in policy and strategy; 2) advising; 3) assisting in monitoring performance; 4) right to receive necessary information; 5) receive reports on progress; 6) conduct regular structured visits to monitor progress; 7) review of financial reports; and 8) assist in the appointment of staff and monitor investigation and resolution of complaints. These roles bear out an approach to participation similar to General Comment 14 and the Alma-Ata Declaration.

The National Department of Health has also developed an Ideal Clinic programme, a quality improvement strategy for primary care services (Department of Health, 2018). The Ideal Clinic includes a health committee linked to a facility as a prerequisite for an ‘ideal clinic’. In the 2018 version of the Ideal Clinic document, a checklist for health committees includes a standard to which all health committees are expected to function. According to this checklist, committees should address complaints, discuss human resources and community needs, and engage in how operational plans should meet these requirements (Department of Health, 2018). However, in the 2020 version, this checklist is not part of the manual.

South Africa is currently restructuring its health system by introducing Universal Health Coverage with a National Health Insurance Bill (NHI) (Department of Health, 2019). Though early versions of the NHI Paper included references to health committees, the NHI Bill of 2019 has omitted all references to these statutory bodies. The NHI Bill of 2019 makes no mention of health committees or what role they would play in the policies shaping Universal Health Coverage.

Provincial legislation

Though the National Health Department provides framework legislation for health committees, it is the provinces’ prerogative to create legislation for these committees. All South Africa’s nine provinces have some form of guideline or legislation on health committees. However, there is no standardization of roles or how committees are constituted across provincial policies or guidelines (Haricharan, Reference Haricharan2015).

The Western Cape Province was the first South African province to draft a policy for community participation structures in 2008 with the Draft Policy Framework for Community Participation/Governance Structures in Health (henceforth the Western Cape Draft Policy) (Western Cape Health Department, 2008). Four clear roles were outlined suggesting that health committees were: a) To provide governance; b) to take steps to ensure that the needs, concerns, and complaints of patients and communities were addressed by the facility; c) to foster community support for the facility and its programmes; and d) to monitor the performance, effectiveness, and efficiency of the facility. The Western Cape Draft Policy envisioned a tiered structure for community participation and viewed health committees as structures that patients and communities should elect. Thus, this policy resonates strongly with human rights and PHC approaches in considering health committees as governance structures.

However, this policy was never formally adopted or implemented, leaving health committees in a policy vacuum (Meier, Pardue and London, 2012). After a protracted period of engagement between the Provincial Health Department and community structures, the Western Cape Health Department passed the Western Cape Health Facility Boards and Committees Act (2016) (hereafter the Act or the Western Cape Act). This Act amended the existing Western Cape Health Facility Boards Act (2001) to include health committees within its ambit. Health Facility Boards are linked to hospitals, whereas health committees are linked to PHC facilities.

Formalized community participation

There is increasing evidence that community participation can have a positive impact on health systems (McCoy, Hall and Ridge, Reference McCoy, Hall and Ridge2012), including ensuring better services (Loewenson et al., Reference Loewenson, Rusike and Zulu2004; Baez and Barron, Reference Baez and Baron2006; Glattstein-Young, Reference Glattstein-Young2010) and better health outcomes (Gryboski et al., Reference Gryboski, Yinger, Dios, Worley and Fikree2006). In South Africa, Padarath and Friedman (Reference Padarath and Friedman2008) concluded that community participation provides community members and health care workers with an opportunity to become active partners in addressing local health needs.

Despite these examples of the positive impact of participation, many studies also point out that participation often offers limited influence. For instance, in their review paper, George and colleagues (Reference George, Mehra, Scott and Sriram2015) found that communities were primarily involved in health promotion interventions and less in governance. Community members were mostly engaged in the implementation of programmes (95%). A Kenyan study similarly highlights health committees’ limited participation in governance (Kessy, 2014).

In many low- and middle-income countries, health committeesFootnote 3 are the predominant form of community participation. Often these committees are linked to a specific facility. In contrast with the facility-based health committees, Brazil has structured community participation around municipal health councils and health conferences. Brazilian health councils have extensive powers and spending oversight. For instance, federal funding depends on municipal health council approval of health plans (Cornwall and Shankland, Reference Cornwall and Shankland2008). Brazil’s system also differs in involving participation in policy processes, which occurs through health conferences at various health system levels, from local to national (Coelho, Reference Coelho, Cornwall and Coelho2007; Cornwall and Shankland, Reference Cornwall and Shankland2008).

Methods

This paper aims to assess whether the Western Cape Health Facility and Boards Act (2016) Act is likely to result in effective and meaningful participation in line with a PHC and human rights approach to participation and whether it addresses barriers identified in practice. It uses the findings from a mixed-methods study conducted in the Cape Town Metropole in the analysis. The research on practised participation – consisting of a survey, observations, focus groups, and interviews – have been presented in a linked paper. It found that practised participation was both limited and ineffective. Health committees existed at only 55 % of Cape Town’s clinics, and many of the existing health committees struggled with sustainability and functionality. Additionally, health committees played limited roles compared to the PHC and human rights framework, as they mainly assisted the clinic with operational tasks. Health committee participation was also limited in the sense that they had no involvement in policy processes. Also, their degree of influence in decision-making was low. In other words: they had little effect on health governance. They also had limited access to upstream influence in the health system as there were no links to other structures or the political level. The study identified several factors impacting health committees: lack of clarity on their role, facility managers and ward councillors’ limited attendance at meetings, health committee members’ limited skills, lack of resources, and support. Further, unclear formation processes resulted in many health committee members being aligned with the facility rather than representing communities. Based on this conclusion, this paper asks whether the Western Cape Act is likely to result in more effective and meaningful forms of participation.

We first provide an analysis of key aspects of the Western Cape Health Facility Boards and Committees Act (2016), identified as critical aspects in the research on practised participation: 1) formation process and composition; 2) roles and degree of influence; 3) upstream influence; and 3) support. This analysis is then used to compare the content of the Act in these four areas to practised participation and to the PHC and human rights framework for participation to determine whether the Act is in accordance with the international framework and addresses challenges experienced in practice.

Based on these comparisons, we discuss how health committee participation could be strengthened in the NHI and the Western Cape legislation. We make recommendations on how to provide a legislative framework for effective and meaningful community participation in line with a PHC and human rights framework.

Findings

Formation process and composition

In contrast with the NHA, the Western Cape Act makes it clear how health committees are established. The Act embraces a model of ministerial appointments (Western Cape Health Facility Boards and Committees Act, 2016: ss6(1)), where the provincial minister, also referred to as the MEC (Member of Executive Council) or a representative of the MEC, appoints 12 members to each health committee. Appointments will be based on nominations from a body that, in the opinion of the MEC, is sufficiently representative of the interests of the community or communities concerned (ibid: 6(3)(a)). The Act follows the NHA in its composition of health committees as constituted by the head of the primary health care facility, one or more councillors of the municipal council in the area and community members. The head of the primary health care services is often referred to as the facility manager. Furthermore, the Act (ibid: ss6(7)) prescribes that the MEC should pay attention to age, gender, race, and disability issues.

Roles and degree of influence

An equally important part of the legislation is the prescription of health committees’ roles.

In the Act, roles are split into duties defined as roles that health committees must perform, and powers defined as roles that a committee may perform. All roles are related to a primary health care facility. Table 1 outlines duties and powers, respectively.

Table 1. Duties and powers of health committees in the Western Cape health facility boards and committees act 2016

A vital clause concerning health committees’ roles appears in section 14 of the Act, which gives the MEC the power to revoke or extend roles. The clause states that changes to the prescribed roles should be in the public’s interest. Changes are supposed to happen in consultation with the health committee in question and be based on an assessment of the health committee’s capacity to perform a particular duty.

Support and linkages to other structures

Notably, there are some provisions for support in the Western Cape Act. The facility manager must ‘take measures to assist the Board or Committee concerned to perform its duties and exercise its power’ (2016: ss16(3)(a)). Some concrete provisions for support are also mentioned. First, the facility is obliged to provide a venue, and ‘in so far as is possible, secretarial, administrative and financial accounting support required by the Committee’ (ibid: ss18(4)). Second, the Department must provide induction and training for newly appointed members and additional training if considered necessary and appropriate (ibid: ss18(8)). Third, a provision related to offering transport reimbursement is included in the Act (ibid: ss25(3)(b)).

A section worth attention is the linkages to other structures. On this point, the Act states that the facility manager may take measures to ensure a collaborative working relationship between health facility boards, committees, and district health councils (ibid: ss16(1)).

Analysis and discussion

Appointed participation

The appointment model, where health committees are formed through a ministerial appointment process, is similar to practices in those committees where the facility managers initiated their formation in the sense that it is the health services that control membership. Appointed participation is in contrast with community-led formation, which was practised in some communities. The linked paper showed that when facility managers appoint health committees, committees may align themselves with the facility rather than represent community interest. This raises the question of how community representatives appointed by the MEC and the Minister’s representatives, such as facility managers, will represent communities.

According to the Act, communities can nominate people. The nomination process is an opportunity to ensure community input. However, the fact that appointments will be based on nominations from a body that, in the opinion of the MEC, is sufficiently representative of the community’s interests means that the minister has the ultimate say in who can represent communities. Depending on how the word ‘body’ is understood, the process may exclude groups, sections, and individuals who are not part of community structures and unorganized social movements. The minister, in other words, has the discretion to decide who are representative of communities.

The appointment model is not only practised in the Western Cape Province. In seven out of South Africa’s nine provinces, health committees are appointed (Haricharan, Reference Haricharan2015). In the remaining two, community organizations elect committees. In the international literature, there are only a few examples of elected committees. Often there is a lack of clarity on who elects the committees. Elections are said to be practised in Kenya (Sohani, 2009), while participatory structures in Peru have some elected members (Iwami and Petchey, 2002). However, there is limited information on the election process – in particular, who constitutes the electorate. Similarly, when Coelho, Pozzoni and Cifuentes (2005) write about elected health council members in Brazil, they refer to members elected to represent specific sectors (mostly civil society organizations). It is these sectors that elect their representatives. There is a shortage of information on the processes leading to electing these members, note the authors. Of importance is that when the literature talks about elected structures, this does not necessarily imply that the electorate consists of all people residing in a specific area.

Sector representation, where sectors within the community elect their representative to the health committee, is practised in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province and some areas in Cape Town. While the model seems to allow for more community representation, it is important to consider the rationale behind giving preference to certain categories. For instance, in both the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape, traditional healers are represented, as are local businesses. One might ask why groups such as migrants and the LGBT community – groups known to face barriers when accessing health care – are not considered (Human Rights Watch, 2009; Muller, 2017).

Neither the Alma-Ata Declaration nor the General Comment 14 deal with how participatory structures are formed. The issue is also not addressed in most South African national legislation. The White Paper (1997) is an exception, as it explicitly talks about communities electing health committees. The Western Cape Draft Policy also viewed community representatives as people elected by patients and communities.

The appointment model should also be viewed in relation to participatory theory, human rights, and PHC approaches to participation, which agree that one of the purposes of participation is to give a voice to marginalized citizens (Potts, 2008; Hilmer, 2010). To what extent structures appointed by the MEC will represent community interest, particularly marginalized voices, is a contentious issue.

Hence, there is a conceptual gap with regard to representation. There has been a lack of attention to how formation models can ensure that community participation structures represent communities.

Overall, there is a need to rethink how community participation structures are formed and the ramifications of different formation processes in research, international frameworks, national, and provincial policies. Two models are emerging: the appointment model, where health services choose community representatives, and the community-based model, where community structures choose or elect community representatives. Elections can be either by sectors or by patients and people residing in the community.

Limited roles and influence

The roles in the Act are inconsistent with a PHC and human rights approach, where participation is about decision-making influence in health governance. In relation to health committees’ duties (roles), it is evident that health committees do not have roles in health governance – in priority setting, planning, implementation, and accountability. It is equally apparent that their influence in decision-making is limited. Consider the language used to outline their duties. They can assist communities in communicating their needs but have no power in ensuring that the facility addresses those needs and no input in how they should be addressed. They can provide constructive feedback, but the facility has no obligation to respond to the feedback or address issues raised.

Concerning health committees’ powers (roles), similar issues are evident. Again, the language used is illustrative. They can request feedback on progress reports and obtain information, but they have no right to expect they get the information since health services are not obliged to provide this. Importantly, it is unclear under which conditions they may perform these powers and who makes decisions in this regard. This makes these powers weak and contingent. Health committees, hence, have no real influence or power to enforce any of these roles. Furthermore, the provision for the MEC to extend and limit the functions of committees gives the MEC absolute power to determine health committees’ roles and define the terms of participation. Finally, both a PHC and a human rights approach envision policy involvement as an essential part of community participation, but this role is absent in the Act.

The roles prescribed in the Western Cape Act are similar to the roles that health committees played in practice. The analysis of practised participation showed that 70% of health committee activities were limited forms of participation with little influence and decision-making. Instead, committees assisted clinics in day-to-day operational tasks and health promotion campaigns and provided assistance to patients with health and social needs. Roles in the Act stipulating that committees should encourage volunteers to offer their services, raise funds for the clinic and foster community support reflect a similar view – that health committees should assist clinics and be an extra pair of hands.

The current Act, then, is likely to provide for a continuation of health committees playing narrow roles incongruent with how participation is conceptualized in PHC and rights-based frameworks, namely as decision-making in health governance. Neither does the Act involve influence in policy development and implementation. In doing so, it falls short of the transformative potential of community participation in health systems.

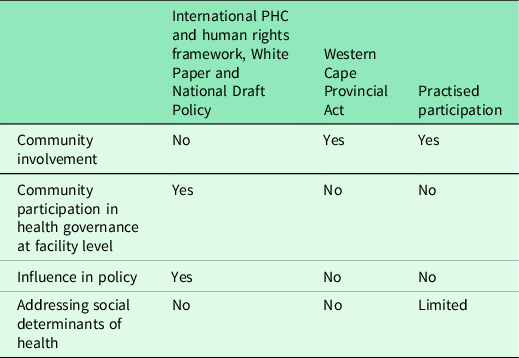

In the linked paper, we outlined four domains for health committee participation, including a distinction between involvement and participation, with involvement being the way health committees practised their role as practical support. In contrast, participation was defined as influence in health governance. Besides these first two domains, we argued that health committees’ access to influence in policy and addressing social determinants of health should be considered. Table 2 provides an overview of these four domains mentioned in different policies and frameworks and as practised by health committees in the linked study. This overview shows how roles in the Western Cape Act are similar to how health committees practised participation but in contrast with international frameworks, the White Paper, and the National Draft Policy.

Table 2. Roles of health committees in policies and as practised by health committees

Considering how community participation should be conceptualized along these domains could be the first step in creating meaningful structures. These should build on the PHC and human rights framework but address gaps, such as whether participatory structures should also be concerned with social determinants of health. Furthermore, the issue of how to ensure that community participation structures sufficiently represent communities needs careful deliberation.

Upstream influence

An important aspect in both a rights-based and a PHC approach is that participation should occur at local, national, and global level. As the description of roles has demonstrated, health committees are considered localized participatory structures focusing on local health facilities. There are no roles that suggest influence at other levels. While focusing on the local level may be important, health committees are likely to encounter issues that need to be addressed higher up in the health system and at a policy level. This was evident in the paper on practised participation, where health committee members complained about their lack of access to the wider health system and the political system. They asserted that without access upstream, they could not address issues encountered sufficiently.

Upstream influence could occur through linkages to other structures. An essential feature in the Act is the limited articulation of collaborative, participatory structures horizontally and vertically. Although the facility manager may take measures to ensure collaborative working relationships between health facility boards, committees, and district health councils (2016: ss16(1)), there is no obligation to ensure that this occurs. Like with many other provisions in the Act, this is framed as an option. Further, there are no structural linkages for upstream influence in the health system to district, provincial, and national level. In fact, the Act does away with coordinating structures that have existed at subdistrict and district level. Tiered structures for community participation – from local to sub-district and district level – had existed in Cape Town since 1992 when the Cape Metro Healthcare Forum, an umbrella body for health committees in the Cape Town Metropole, began to organize health committees. They are also envisioned in the Western Cape Draft Policy. Along a similar line, the White Paper talks about health conferences at local, provincial, and national level. Again, the Act represents a departure from the White Paper and the Western Cape Draft Policy’s attempts to ensure coordination and upstream influence.

Enabling environment

The analysis of practised participation in the linked paper identified sustainability and functionality as two critical challenges for effective and meaningful participation. The paper also outlined several issues that impacted these challenges. Foremost among these was a lack of resources. The research demonstrated that resources such as funds for transport reimbursement, running costs, and activities were necessary for committees to functions effectively. Health committee members come from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds and cannot – and should not – be expected to carry the cost of participation.

Health committee members’ lack of capacity, which was linked to their background and limited education, was another critical factor. The data on practised participation showed that there was are a correlation between health committee roles and members’ skills. The fact that they were not capacitated impacted negatively on which roles they were able to fulfil. The data indicated that health committee members would like to take up more expansive roles if they had the skills. Finally, the data suggested that the attitude of facility managers and ward councillors toward health committee participation was critical to how the committees functioned. Support from facility managers and ward councillors was raised numerous times, as was the importance of taking health committee members’ educational, social, and economic context into consideration.

The Act does address some of the challenges identified to impact negatively on health committees. The existence of health committee legislation means that health committees become statutory structures with a legal mandate. Notwithstanding the issues raised around appointed participation, having the MEC and the Health Department appoint committees may result in more committees being established and committees becoming more sustainable and functional, which may also result in facility managers being more responsive and supportive.

The Act makes provisions for support, which may result in more effective participation. There is a provision that the facility manager must take measures to ensure that the health committee performs its duties (2016: ss.16(3)(a)). Here, the minister’s role is framed as an obligation, though there is little detail on what this obligation entails. The paper on practised participation showed that facility managers did not always attend health committee meetings despite a legal requirement in the NHA. We argued that making it part of the facility managers’ key performance areas might improve their participation. Such a condition is likely to result in facility managers ensuring measures to support health committees. It is also worth noting that having a health committee is a requirement for the Ideal Clinic checklist. This vital provision may impact facility managers’ investment in health committees.

An important provision is that the facility is obliged to provide a venue. This is an essential step, addressing a problem identified in the research on health committee practice. The other forms of support, such as secretarial, administrative, and financial accounting support (2016: ss18(4)), are made conditional, depending on whether they are deemed possible. Hence, while there is a commitment to support, some provisions are expressed as optional, where framing them as an obligation would be preferable. There is a danger that framing support as optional will undermine some committees. It is also worth considering whether it would not be a better option to provide health committees with training to function without this support. Capacitating health committees would ensure both their functionality and independence.

The Act also make provision for induction and training for newly appointed members and additional training if considered necessary and appropriate (2016: ss18(8)). This is an essential provision that, like the Alma-Ata, recognizes the importance of education and training. The research on practised participation highlighted the importance of training and showed a correlation between health committee members’ skills and roles.

The final provision relates to providing reimbursement for transport expenses (2016: ss25(3)(b)). This is a necessary provision, as the research on practised participation demonstrated that the cost related to participation sometimes resulted in health committees becoming ineffective or folding altogether.

While the Western Cape Act has some provisions for support, it is imperative to note what is absent in the Act. Consider, for instance, that there is provision made only for transport costs but no other expenses such as for phones and stationery. Again, the research on practised participation made it clear that running costs for the committees were a necessity. It also showed that health committees needed funding for running health projects.

Overall, the Act makes some provision for support that may result in more effective committees, and it addresses some of the challenges experienced by health committees in practice. Still, without sufficient funding for running costs and adequate training, health committees are likely to continue struggling with sustainability and functionality.

In summary, the Act may result in more health committees being established in the Western Cape. These committees may be more effective and functional due to their status as legislated structures with a mandate and some support. On the other hand, health committees are unlikely to have much influence due to the limited roles prescribed in the Act. They are unlikely to practise a meaningful form of participation in line with a PHC and human rights approach.

Recommendations

The research points out that there are two distinct conceptualizations of community participation. In the first, community participatory structures such as health committees have narrow roles and limited influence. This conceptualization is reflected in the Western Cape Act and practised participation. In the second conceptualization, participation is viewed as influence in decision-making in health governance. This view is reflected in the PHC and human rights framework. The South African White Paper, National Draft Policy, and the Western Cape Draft Policy all are in concordance with the international framework, while the NHI is silent on participation.

We propose that the Western Cape Act be amended to address the shortcomings. At the same time, we suggest that South Africa’s National Health Insurance Bill should contain provisions for health committees. We recommend that the National Department of Health take a stewardship role in ensuring that provincial and national policies on health committees are aligned rather than the present disjuncture between national policies and those at the provincial level, such as the Western Cape.

For the Western Cape Act and the NHI Bill, we suggest the following:

-

1. Legislation should provide an explicit conceptualization of participation, which should institutionalize more meaningful forms of participation for communities and describe a vision for community participation aligned with the international PHC and human rights framework.

-

2. We propose that the State draws on the international framework, the White Paper and the National Draft Policy to conceptualize health committees as structures primarily involved in health governance, including accountability, at facility level. They should ensure that health services meet the needs of communities and are accountable. Additionally, these structures should be concerned with social determinants of health and have input at policy level.

-

3. To facilitate upstream influence and influence on policy level, we suggest a tiered structure for community participation with health committees functioning at the local level.

-

4. We also propose that the NHI Bill contains sections on how health committees are supported to become more meaningful and effective structures.

-

5. We suggest that the Western Cape Act includes more supportive measures.

-

6. Finally, we suggest that careful consideration be given to the formation process and the composition of health committees. This should ensure that they adequately represent communities.

Conclusion

This study found that the Western Cape Health Facility Boards and Committees Act (2016) is likely to result in a form of limited participation that is inconsistent with a PHC and human rights approach to participation, which define participation as influence in health governance. The Act’s description of roles is in line with how health committees practised participation. It is, therefore, likely that health committee participation will continue to take a limited form.

The National Health Insurance Bill (2019) presents an opportunity to rethink community participation and stipulate substantive roles for health committees in the South African health system. A PHC and human rights-based approach to participation echoed in the South African White Paper on Transformation of the Health System (1997) and the National Draft Policy on Health Governance Structures (2013) could be used to define health committee roles and develop structures for meaningful participation.

A meaningful form for participation could entail that health committees are defined as governance structures at the facility level. Health committees could also have substantial roles in addressing social determinants of health. They should have access to address issues at policy level either directly or through a tiered community participation system.

The Act embraces an appointment model, where the Provincial Minister or Health appoints health committees. Research has shown that this formation process may result in committees that do not sufficiently represent communities. The study draws attention to a need to consider how to ensure that health committees adequately represent communities. It argues that community-led models may represent communities better.

Finally, the Act contains some provisions of support for health committees, which may result in more effective participation. However, most of the support is contingent and needs to be expanded to address challenges impacting health committees’ sustainability and functionality.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the health committee members who participated in this research.

Financial support

Africa Netherlands Program for Alternative Development (SANPAD) (L.L. project number 07/35); National Research Foundation, South Africa (NRF) (L.L. grant No: 73 658); International Development Research Centre (IDRC) (L.L. grant number: 106972-002); the European Union (L.L. Grant number: DCI-AFS/2012/302-996); and the Wellcome Trust (H.J.H. grant number: 108 645/Z/15/Z).

Conflicts of interest

None.