The belief that smoking alleviates anxiety, or stress as it is commonly known in the general population (i.e. is anxiolytic), is highly pervasive. Almost half the smokers in England cite stress relief as one of the main reasons for smoking. Reference Fidler and West1 This stands in contrast to the evidence from numerous laboratory studies that fail to detect mood enhancing effects of nicotine. 2 Smoking appears not to reduce stress in smokers who are not nicotine deprived; instead, levels of stress in smokers after smoking are similar to those of non-smokers. Reference Parrott3 It has been suggested, therefore, that the perceived beneficial effects of smoking upon stress are actually a misattribution of withdrawal relief. Reference DiFranza and Wellman4,Reference Parrott5 There is further research to suggest that smoking may actually be a risk factor for the development of anxiety-related disorders. Reference Kassel, Stroud and Paronis6 Findings such as these suggest that smoking may actually cause stress, but fosters the impression in smokers that it alleviates stress, due to nicotine's ability to quickly reverse the symptoms of withdrawal. Reference Hajek, Taylor and McRobbie7 The belief that smoking relieves stress serves as a major barrier for smokers to quit, 8 and for health professionals to recommend quitting. Health professionals also believe that smoking is anxiolytic and that smoking cessation worsens mood. Reference Dickens, Stubbs and Haw9,Reference Praveen, Kudlur, Hanabe and Egbewunmi10 This belief is particularly detrimental to those with psychiatric disorders, who are less likely than other smokers to be offered cessation advice and support Reference Campion, Checinski, Nurse and McNeill11 despite having a life expectancy around 20 years lower than people without such a disorder. Much of this loss is attributed to cigarette smoking, Reference Brown, Barraclough and Inskip12 which is more prevalent in this group. Reference Lawrence, Mitrou and Zubrick13

Although it is well documented that anxiety tends to increase in the first few days of a quit attempt due to withdrawal from nicotine, Reference Hughes14 it remains unclear what happens in the longer term once the initial withdrawal phase has ended (normally after 2–4 weeks). Reference Hughes14 Two studies report associations between prolonged abstinence and reduced stress. Reference Hajek, Taylor and McRobbie7,Reference Cohen and Lichtenstein15 These are limited, however, by small sample sizes, lack of sample representativeness and lack of validated measures of anxiety. Evidence in populations with psychiatric disorders is even more limited, although indirect evidence refutes assertions of a negative impact. A systematic review of enforced smoking bans in in-patient psychiatric settings found no evidence of increased aggression, use of seclusion, discharge against medical advice or increased use of as-needed medication following the ban, Reference Lawn and Pols16 although the review did not record whether in-patients actually stopped smoking or not.

The current paper aims to build on these findings using more rigorous methods. The sample for the current study is drawn from smokers from the general population and uses validated measures of key outcomes (anxiety and smoking status) and hypothesised moderators (current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and motivation to smoke for coping as opposed to pleasure). Furthermore, the study represents, to our knowledge, the first assessment of the effect of quitting smoking on anxiety among those with a current mental disorder and the first investigation into the long-term consequences of failing to quit smoking on mental health. This is important because most people who try to quit smoking fail to achieve abstinence on any single quit attempt and require multiple attempts. If failed attempts were harmful to mental well-being, there would be even more imperative to ensure that the chances of success were maximised with available effective interventions. A recent study of people with a history of clinical depression reported that both depression and anxiety scores deteriorated in a quit attempt following relapse to smoking. Reference Berlin, Chen and Lirio17 This may suggest a concern, but the follow-up was less than 3 months and most results were not statistically significant. The data are therefore inconclusive. The primary aim of this study was to assess changes in smokers' anxiety following a quit attempt in those who succeeded in remaining abstinent and those who relapsed. We also examine whether the changes associated with abstinence are modified by the presence of a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and by whether smoking for stress relief was a prime motive for smoking.

Method

Study design

This was a prospective cohort study involving secondary analysis of data from a smoking cessation trial (ISRCTN14352545, details of the trial are published elsewhere). Reference Marteau, Munafò, Aveyard, Hill, Whitwell and Willis18,Reference Marteau, Aveyard, Munafò, Prevost, Hollands and Armstrong19 Ethical approval for the trial was sought and obtained (Hertfordshire 1 Research Ethics Committee, reference 06/Q0201/21; Medicine and Healthcare Products Regulatory Authority, reference: 24570/0002/001-0001).

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from the practices of 29 primary care physicians in two English cities to participate in an open-label, parallel group, randomised controlled trial conducted in primary care. Participants smoking at least 10 cigarettes a day, who wanted to quit and were 18 years or older were eligible for inclusion. Potentially eligible participants were identified from practice registers and mailed a letter from their primary care physician expressing concern about their smoking and offering assistance to quit, with an invitation to participate in the trial. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. A total of 633 agreed to participate in the trial and were randomised, of whom 491 provided data at both baseline and 6 months for the measure of state anxiety. Recruitment began in June 2007 and all data collection was completed by September 2009.

Interventions

The trial took place in UK National Health Service (NHS) smoking cessation clinics based in primary care. These provide a combination of behavioural support, education and pharmacotherapy to assist smokers to quit. All participants were prescribed a nicotine patch with the dose based on heaviness of smoking. Those who smoked 15 or more cigarettes a day were prescribed 21 mg patches and those smoking 10–14 cigarettes a day were prescribed 14 mg patches. In addition, participants were randomised to receive an additional oral nicotine replacement therapy dose, based either on their genotype (genotype arm) or nicotine dependence (phenotype arm), either of 6 mg or 12 mg a day.

Procedure

Participants attended a total of 8 weekly clinic appointments with a research nurse. In the first clinic session participants completed baseline measures – including anxiety. Participants started their quit attempts either immediately following the third clinic visit or the following morning. At this appointment the rationale for participants' additional oral nicotine replacement therapy doses, based on the group to which they had been randomised, was given. All participants were contacted 6 months following their quit dates, either by telephone or by post. Follow-up questionnaires were completed and, in those indicating continued abstinence, a salivary sample was requested by post and subsequently analysed for cotinine.

Measures

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the six-item short form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-6). Reference Marteau and Bekker20 This measure has high internal reliability (α = 0.89 and 0.75 for baseline and 6 months respectively) and is a validated short form of the original 20-item state scale of the STAI. Reference Court, Greenland and Margrain21,Reference Tluczek, Henriques and Brown22 Scores range from 20 to 80 with a population norm of 35.

Smoking status

Prolonged abstinence from smoking at 6 months, defined as sustained abstinence after an initial 2-week grace period, was assessed using self-reported behaviour with biochemical validation as recommended for clinical trials. Reference Hughes, Keely, Niaura, Ossip-Klein, Richmond and Swan23 Participants were considered to be prolonged abstinent if they reported that they had smoked no more than five cigarettes since the start of the abstinence period, and had a salivary cotinine level of less than 15 ng/ml. Initial abstinence from smoking at 4 weeks was assessed as per usual clinic practice after quit date with self-reports of abstinence validated by expired-breath carbon monoxide reading assessed using a Bedfont Smokerlyzer (Rochester, UK). Participants were considered to be abstinent if they reported not smoking a single puff during the previous week and had a carbon monoxide reading of ⩽9 parts-per-million; all others were considered as having relapsed. In each case, non-responders or invalidated self-reports of behaviour were counted as smoking.

Motives for smoking

Motives for smoking were assessed at baseline by responses to a single item ‘Do you smoke mainly for pleasure or because it helps you to cope?’ Participants were asked for one of three possible responses ‘mainly for pleasure’, ‘mainly to cope’ or ‘about equal’. Those reporting smoking primarily for pleasure have been found to be significantly more likely to achieve abstinence than those reporting smoking primarily to cope. Reference Ferguson, Bauld, Chesterman and Judge24

Current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder

At baseline, participants were asked to report their current medical history and use of medication, including psychiatric history. All those who reported being on medication were asked to bring in the repeat medication ordering slip generated by their general practitioner for verification. In the case of someone who brought in a slip and gave a clear and consistent account of their current and past history, no further checking was done. If a participant was unclear about their medical history, or forgot to bring their repeat medication ordering slip, we consulted their primary care record. Records were not checked for those who denied being on repeat medication. Reported diagnoses of psychiatric disorder (n = 106) were primarily mood (53%, 56/106) and anxiety (13%, 14/106) disorders. A further 24% (25/106) reported multiple disorders. In total, 83% (88/106) of those reporting a current psychiatric disorder were on psychiatric medication.

In addition, baseline data were collected on demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (assessed using educational qualifications) and nicotine dependence (assessed using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) Reference Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker and Fagerstrom25 ).

Statistical analyses

We used linear regression to examine anxiety at follow-up in relation to smoking status, classified as relapsed or abstained. Baseline STAI-6 (anxiety) score was mean-centred. For ease of interpretation, the anxiety score at follow-up was centred on the baseline mean so that regression coefficients represented the change in anxiety score. All other continuous variables were mean-centred and all categorical variables entered as dummy-coded variables. We conducted complete-case analyses, as rates of missing data were low (Table 1).

In the initial model, only abstinence status and baseline anxiety score were entered. Thereafter, potential confounders were added; age, gender, ethnic group. In addition, variables that appeared unbalanced between those who had abstained or relapsed were also included; namely cigarettes per day, nicotine dependence score, trial arm and dose of nicotine replacement therapy used. We compared anxiety change score in those who had relapsed or abstained (adjusted only for baseline rating) with the fully adjusted estimates by calculating the latter using the mean of the various other covariates.

We examined whether a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder or motive for smoking modified the association between abstinence and change in anxiety score. To do so, we added both a term representing a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder (for example) and its multiplicative interaction with abstinence and reported the F-test for this step. Each term tests whether the change in anxiety differs from all other individuals who have relapsed or abstained.

People with a clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorder typically have a score of 50 or higher on the original 20-item state scale of the STAI. Reference Spielberger26 In order to create scores comparable with the larger scale, participants' raw scores on the STAI-6 (range 6–24) were divided by 6 and multiplied by 20. Participants with scores ⩾50 were classified as having high anxiety and the likelihood of being in the high-anxiety group at follow-up, conditional upon baseline group status, was computed using conditional logistic regression.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics, smoking-related variables, current psychiatric disorders, and motives for smoking

| Abstinent participants (n = 68) | Relapsed participants (n = 423) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 35 (51.5) | 186 (44.0) |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | ||

| White | 64 (94.1) | 380 (89.8) |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | ||

| No qualifications | 23 (33.8) | 119 (28.1) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 15 (22.1) | 103 (24.3) |

| A-levels or equivalent | 8 (11.8) | 47 (11.1) |

| Further education | 7 (10.3) | 55 (13.0) |

| Degree or other higher education | 7 (10.3) | 73 (17.3) |

| Other | 8 (11.8) | 26 (6.1) |

| Trial arm, n (%) | ||

| Genotype | 43 (63.2) | 211 (49.9) |

| Nicotine replacement therapy dose, n (%) | ||

| 21 mg patches | 51 (75) | 339 (80.1) |

| 12 mg equivalent daily doseFootnote a | 6 (8.8) | 96 (22.7) |

| Cigarettes per day, mean (s.d.) | 18.7 (7.8) | 21.0 (8.9) |

| Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence, mean (s.d.) | 4.8 (2.0) | 5.7 (2.2) |

| Diagnosis of psychiatric disorder at baseline, n (%) | 10 (14.7) | 96 (22.7) |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||

| Mood disorders | 5 (7.4) | 51 (12.1) |

| Anxiety disorders | 3 (4.4) | 11 (2.6) |

| Other | 2 (2.9) | 34 (8.0) |

| Motives for smoking,Footnote b n (%) | ||

| Mainly for pleasure | 19 (27.9) | 85 (20.2) |

| Both | 39 (57.4) | 257 (61.2) |

| Mainly to cope | 10 (14.7) | 78 (18.6) |

a. Equivalent daily dose is absorbed nicotine dose, for example 12×2 mg gum gives about 12 mg absorbed dose

b. Data missing for three participants who relapsed.

Results

Participant characteristics

We followed up 491/633 trial participants (77.6%) at 6 months. There was no difference in baseline anxiety between those who were and those who were not followed up at 6 months (responders mean 38.0 (s.d. = 12.5); non-responders mean 39.4 (s.d. = 13.5), t(612) = 1.09, P = 0.28).

The participants were typical of smokers attending smoking cessation clinics (Table 1). A total of 14% (n = 68/491) were verified as prolonged abstinent at 6 months. We found that 15% of those who abstained (n = 10/68) and 23% of continuing smokers (n = 96/423) had a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder (Table 1). Mean baseline anxiety was within the normal range for individuals who subsequently abstained or continued smoking, respectively.

Association between change in anxiety and abstinence status

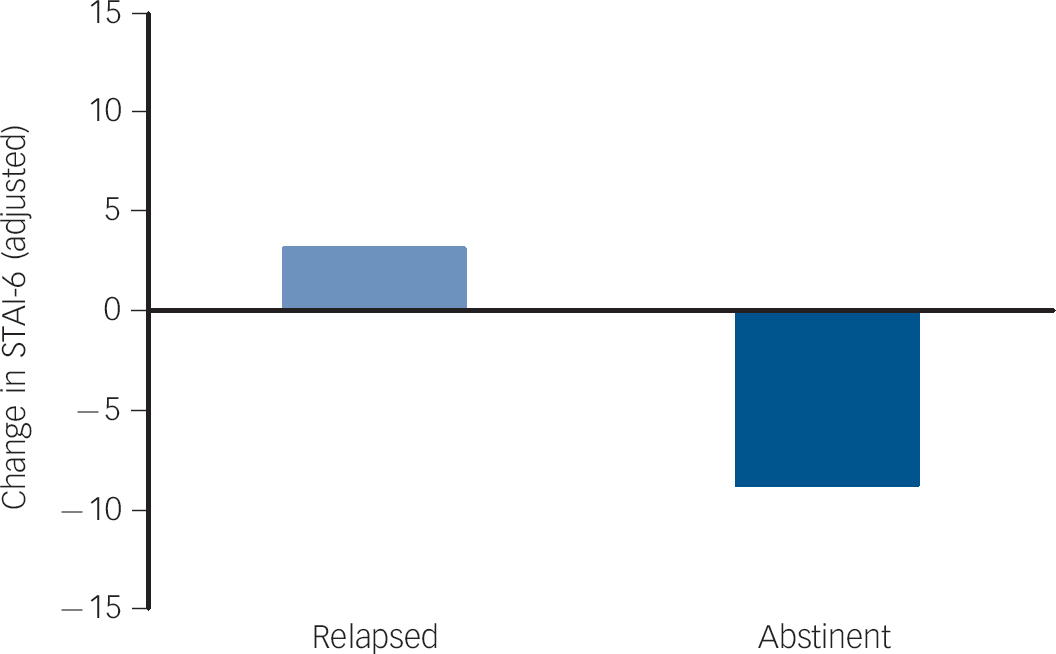

Adjusted for baseline STAI score, there was a significant difference of 12.3 (95% CI 8.2–16.5) points in the STAI score between people who relapsed to smoking and those achieving prolonged abstinence. On further adjustment for age, dependence, cigarette consumption and trial arm this difference was similar at 11.8 (95% CI 7.7–16.0) points. This equated to an increase of about three points for those who did not achieve abstinence and a decrease of nine points for those who did (both coefficients were individually statistically significant) (Fig. 1).

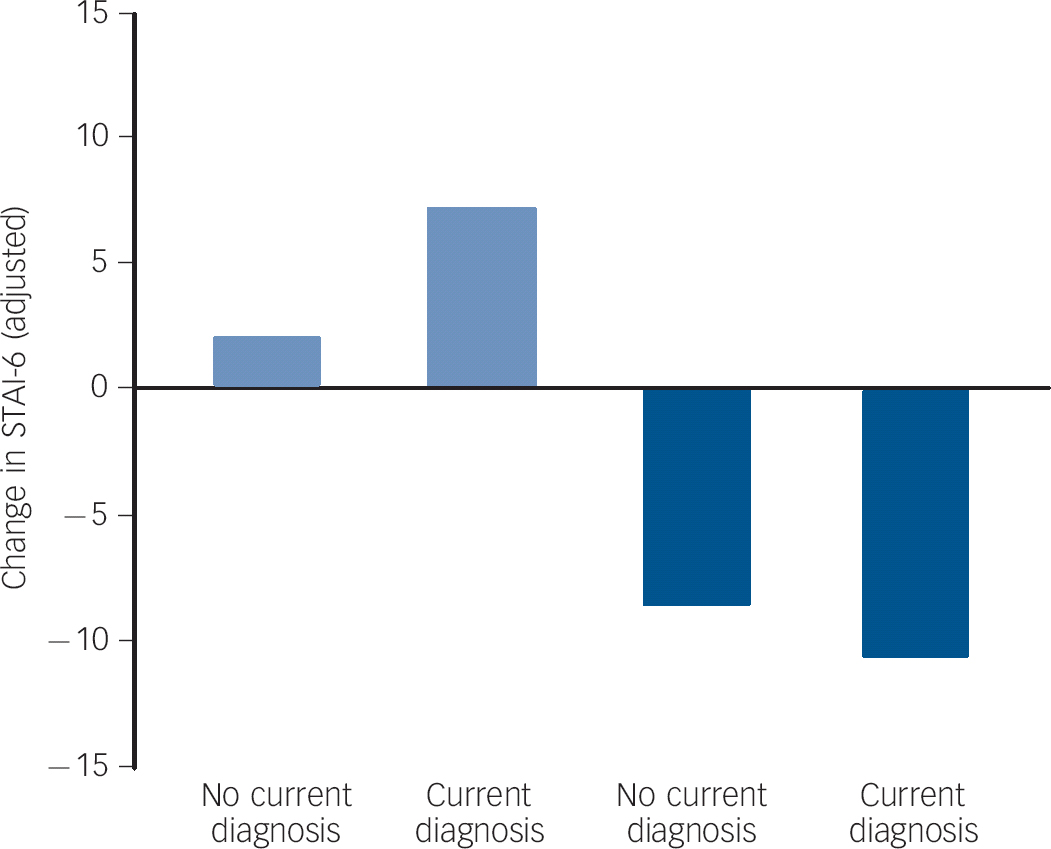

There was reasonably strong evidence that adding terms that allowed the change in anxiety to depend upon the presence or absence of a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder significantly improved the fit of the model (Table 2). The increase in anxiety in those without a current diagnosis was small (two points, Fig. 2) but greater among those with a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder (seven points). The difference between these two groups was statistically significant (Table 2). Although the improvement in anxiety was greater among those with a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder at baseline, this was not significant (P = 0.19).

Fig. 1 Adjusted change in anxiety from baseline to 6 months in relapsed smokers and abstinent smokers overall.

Adjusted for baseline anxiety score, smoking status, age, gender, ethnic group, educational status, trial arm and dose of nicotine replacement therapy, all coefficients set to their means. STAI-6, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

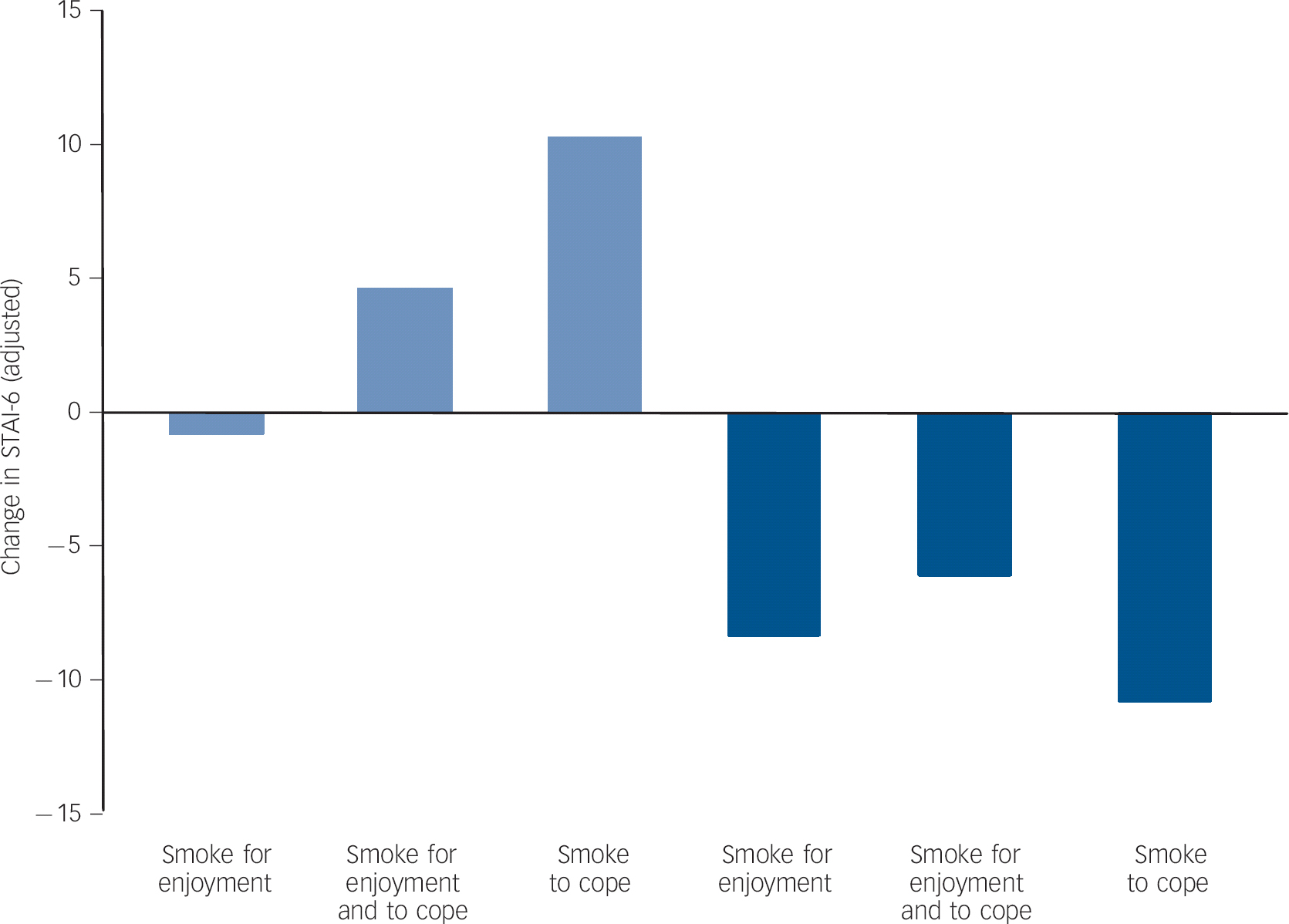

Change in anxiety was modified by motives for smoking, with the model fit improving significantly (Table 2). In people who relapsed, those smoking for enjoyment had no change in anxiety. Those who relapsed who smoked either partly or mainly to cope had increases in anxiety (Fig. 3). Likewise, in those who abstained the decrease in anxiety in those smoking to cope was larger than for the other two groups.

Sensitivity analysis

The increase in anxiety upon relapse was somewhat unexpected, so we checked whether it might be as a result of the participant having to declare relapse to researchers who had provided clinical treatment to assist cessation. We split those who had relapsed into those who relapsed during clinical treatment and therefore had already reported this to the research team, and those who returned to smoking after the end of treatment and were reporting relapse for the first time at 6-month follow-up. In those who relapsed late there was a small, non-significantly lower rise in anxiety at 1.6 (95% CI −4.7 to 1.5) points.

Table 2 Improvement in model fit and coefficients for difference in change in anxiety score between those with and without a psychiatric disorder, or who smoke for enjoyment

| F-test or improvement in model fitFootnote a | Partially adjustedFootnote b | Fully adjustedFootnote c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (d.f.) | P | Adjusted coefficient |

P | Adjusted coefficient |

P | |

| Current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder | 4.77 (2) | 0.009 | ||||

| Relapsed | 5.9 | 0.002 | 5.2 | 0.007 | ||

| Abstinent | –6.7 | 0.24 | –7.4 | 0.19 | ||

| Smoking motives | 5.85 (4) | <0.001 | ||||

| Smoke for enjoyment and to cope, relapsed | 5.1 | 0.009 | 5.4 | 0.006 | ||

| Smoke for enjoyment and to cope, abstinent | –3.6 | 0.46 | –3.2 | 0.50 | ||

| Smoke to cope, relapsed | 12.1 | <0.001 | 11.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Smoke to cope, abstinent | –13.1 | 0.047 | –13.6 | 0.037 | ||

a. For addition of terms representing the presence of the characteristic and its interaction with smoking abstinence.

b. Adjusted for baseline anxiety score and smoking status.

c. Adjusted for baseline anxiety score, smoking status, age, gender, ethnic group, educational status, trial arm and dose of nicotine replacement therapy.

Association between abstinence and case of anxiety disorder

At baseline 22.4% of participants were in the high-anxiety group and at 6-months follow-up this had risen to 28.2%. People who would achieve prolonged abstinence were less likely to be in the high-anxiety group at baseline, with only 14.7% meeting the definition, whereas 23.7% of people who would fail to quit were in the group. At follow-up, the proportion of those in the high-anxiety group among abstinent participants had fallen from 14.7 to 10.3%, whereas among continuing smokers it had risen from 23.7 to 31.0%. Considering the pairing, the odds ratio (OR) for being in the high-anxiety group at 6 months among abstinent smokers was 0.63 (95% CI 0.20–1.91), whereas for relapsed smokers it was 1.58 (95% CI 1.12–2.24). The P-value for the interaction between time and abstinence was 0.009. Three-way interactions between time, abstinence, and the presence of a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder or smoking to cope failed to converge on a solution because of sparse data.

Discussion

Main findings

Quitting smoking was associated with a moderate reduction in anxiety, whereas relapse was associated with a small increase. The decrease in anxiety on abstinence was somewhat larger for people with a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder at baseline and also for people who smoked primarily to cope with stress, although it was significant only for the latter. The increase in anxiety was also larger for these groups, especially for the group that smoked primarily to cope.

Strengths and limitations

This study had some strengths and limitations. Overall, the study was a relatively large smoking cessation study and recruited a representative sample of smokers seeking help to stop, without excluding people with comorbid disorders. The frequent testing of abstinence in the first weeks after quit day and biochemical confirmation at each contact imply our key measure of exposure was accurate and the outcome was measured with a clinically relevant and validated scale. However, relatively few people abstained from smoking, meaning that sample sizes in some subgroups were low, limiting precision and ability to detect associations. Another limitation is that we relied on physician diagnosed disorder and it is possible that general practitioners or psychiatrists may not have followed a coding system in diagnosing these disorders. It is possible that some of those diagnosed with psychiatric disorders did not in fact have a disorder and it is likely that some of those who had no diagnosis did have an undiagnosed psychiatric disorder. In our study, this would have made the groups reporting and not reporting psychiatric disorders more similar and undermined our ability to detect differences between them. The most important limitation is that, like all observational studies, we cannot be sure that the associations we observed were caused by the change in smoking status. It would be practically difficult, and ethically unacceptable, to randomise people to abstain or continue smoking for 6 months. We therefore have to rely on data obtained from non-experimental studies to establish causality.

Fig. 2 Adjusted change in anxiety from baseline to 6 months in relapsed (light blue bars) and abstinent smokers (dark blue bars) by subgroups defined by current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder.

Adjusted for baseline anxiety score, smoking status, age, gender, ethnic group, educational status, trial arm and dose of nicotine replacement therapy, all coefficients set to their means. STAI-6, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Fig. 3 Adjusted change in anxiety from baseline to 6 months in relapsed (light blue bars) and abstinent smokers (dark blue bars) by subgroups defined by motives for smoking.

Adjusted for baseline anxiety score, smoking status, age, gender, ethnic group, educational status, trial arm and dose of nicotine replacement therapy, all coefficients set to their means. STAI-6, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Comparison with other findings

There is good evidence that stopping smoking is associated with reduced anxiety from both the current study and elsewhere. Reference Hajek, Taylor and McRobbie7,Reference Cohen and Lichtenstein15 In the current study the biggest predictor of anxiety at follow-up was baseline anxiety, but the effect size for abstinence was similar (betas 0.27 and 0.26 respectively). Furthermore, baseline anxiety scores were similar between participants who abstained and those who did not. Adjustment for a range of other potential confounders did not materially alter the strength of the associations. Although there are many reasons why anxiety might change over 6 months and which were not measured and therefore not controlled for, there is no reason to imagine that these would be differentially associated with abstinence status. Another explanation is reverse causation, namely that rising anxiety undermined the success of the quit attempt. We measured anxiety 1 week after quit day and neither anxiety measured then nor the change in anxiety at 6 months from baseline was associated with the likelihood of achieving abstinence. We also found that reporting relapse did not influence change in anxiety from baseline. The evidence for causality also comes from the consistency of these results with those from other studies Reference Hajek, Taylor and McRobbie7,Reference Cohen and Lichtenstein15,Reference Berlin, Chen and Lirio17 with no studies to our knowledge producing contrary results. Furthermore, there is a psychologically plausible mechanism – the misattribution hypothesis. There were data in this study that support this mechanism. Those experiencing the largest decrease in anxiety on cessation were the participants with a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder and those who reported smoking to cope. Both these groups were more likely to report smoking within 5 min of waking (50% v. 39% and 50% v. 38% respectively). This is a behavioural marker of being driven to smoke to stave off withdrawal symptoms, which includes anxiety. By stopping smoking and removing these repeated episodes of anxiety, we might expect an overall reduction in reporting of anxiety, as observed.

In contrast, there is less strong evidence that the increase in anxiety on failure to quit smoking is caused by the change in smoking status. There is only one other report of this to our knowledge. Reference Berlin, Chen and Lirio17 There is no obvious causal mechanism other than those who relapse feeling concern arising from the continuing health risks of their smoking. However, we might expect this concern to return to baseline levels relatively soon after relapse, but there was no difference in 6-month increase in anxiety in those who relapsed early and those who relapsed late. Furthermore, almost all participants had tried to quit previously, so failure to attain abstinence was not a new experience. Nevertheless, there is no other obvious reason for the increase in anxiety, and the increase seen in people who smoked to cope was clinically significant. This finding therefore warrants further attention given many smokers make repeated attempts to quit.

Implications

These findings have implications for public health messages about smoking. The belief that smoking is stress relieving is pervasive, but almost certainly wrong. The reverse is true: smoking is probably anxiogenic and smokers deserve to know this and understand how their own experience may be misleading. The finding on the rise in anxiety in smokers who fail to quit has less clear relevance for public health. It may be important for clinicians helping patients to stop smoking, particularly those with a current diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, who were more likely to report smoking primarily to cope than people without such a diagnosis.

In summary, stopping smoking probably reduces anxiety and the effect is probably larger in those who have a psychiatric disorder and who smoke to cope with stress. A failed quit attempt may well increase anxiety to a modest degree, but perhaps to a clinically relevant degree in people with a psychiatric disorder and those who report smoking to cope. Clinicians should reassure patients that stopping smoking is beneficial for their mental health, but they may need to monitor for clinically relevant increases in anxiety among people who fail to attain abstinence.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.