Preventing youth suicide is an urgent public health need. Suicide is the second cause of death for young people aged 15–24, and reports of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) have risen in the past 10 years (Curtin & Heron, Reference Curtin and Heron2019; Kann et al., Reference Kann, McManus, Harris, Shanklin, Flint, Queen, Lowry, Chyen, Whittle, Thornton, Lim, Bradford, Yamakawa, Leon, Brener and Ethier2018). Data from both self-reported and clinical assessments suggest that maltreated youth are more likely to consider and attempt suicide (Angelakis et al., Reference Angelakis, Austin and Gooding2020; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012). A recent meta-analysis showed young people who experienced any type of child abuse or neglect were 2.91 times more likely to attempt suicide and 2.36 times more likely to have suicidal ideation compared to their non-maltreated counterparts, respectively (Angelakis et al., Reference Angelakis, Austin and Gooding2020). The prevalence of child maltreatment in the United States is substantial, making its impact on youth suicide alarming. There were over 3.4 million children involved in a child maltreatment investigation in the United States in 2019 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, 2021). Further, estimates show 37.4% of US youth are involved in a child maltreatment investigation by the time they reach age 18 (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Wildeman, Jonson-Reid and Drake2017). Globally, the World Health Organization (2020) estimates approximately one billion children aged 2–17 experience violence such as child maltreatment each year. Thus, suicide prevention for maltreated youth globally is an urgent public health problem.

A large body of research exists on the associations between child maltreatment and suicide risk (for a review, see Miller et al., Reference Miller, Esposito-Smythers, Weismoore and Renshaw2013), but scientists have yet to consolidate this body of knowledge into a conceptual model to guide research and prevention in this area. In the present paper, we argue that suicide prevention for maltreated youth will benefit from integrating theories of suicide with developmental perspectives, which give attention to age-specific mechanisms and antecedents of STBs in this vulnerable youth population. While current theoretical models of suicide (e.g., the interpersonal theory of suicide) specify the causal mechanisms that underlie STBs among adult samples, they have largely not integrated developmental perspectives on youth suicide.

A developmental lens is essential for understanding the etiology between child maltreatment and STBs during adolescence, specifically. Adolescence is a developmental period wherein young people undergo multiple changes at the biological, psychological, and interpersonal levels (e.g., puberty, the development of romantic relationships, and transitioning to spending more time with peers than family members). There is evidence that adolescence is a sensitive period in development with heightened brain plasticity (Fuhrmann et al., Reference Fuhrmann, Knoll and Blakemore2015). This makes adolescence both a time of vulnerability and opportunity. While adolescents are often at risk for the onset of mental health disorders (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005), heightened plasticity during this time confers a “window of opportunity” for preventive programs that build upon youth strengths to prevent suicide (Wyman, Reference Wyman2014).

Overall, a developmental model of the link between child maltreatment and youth suicide will contribute to this research area by offering (a) hypothesized mechanisms underlying the link between child maltreatment and youth suicide; (b) hypothesized risk and protective factors for youth STBs; and (c) implications for preventative efforts. Specifying the role of child maltreatment in the developmental processes leading to youth STBs, as opposed to the role of other childhood adversities (e.g., poverty, parental incarceration, divorce), is an important endeavor due to the unique nature of child maltreatment as a toxic interpersonal stressor and the salience of interpersonal stressors in the etiology of STBs (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010). Children exposed to maltreatment not only experience extreme and often chronic stress, but often do so at the hands of their primary or secondary attachment figures. Ultimately, an integrative developmental conceptual model of the link between child maltreatment and youth suicide will inform targeted prevention efforts to reduce the rates of STBs among youth with child maltreatment experiences.

Consequently, in this paper we will outline the current knowledge on child maltreatment and youth suicide and review the theoretical frameworks that guide our conceptual model, which are primarily the developmental psychopathology perspective and ideation-to-action theories of suicide. Next, based on the literature and our existing theoretical frameworks, we will propose a developmentally informed conceptual model for the association between child maltreatment and suicide risk. The purpose of this conceptual model is to propose developmental pathways from child maltreatment to youth suicide that are based on the existing literature and relevant theoretical models (McGregor, Reference McGregor2018). Note that we do not intend for this model to be exhaustive nor to present a formal causal theory, but instead to offer insight and future directions for research in this specific area. Last, we will discuss implications of this model for advancing efficacious suicide prevention efforts, with a focus on upstream prevention.

Youth suicidal thoughts and behaviors: definitions and overview

We define STBs as including cognitions or actions (non-fatal or fatal) that involve intent to die. Specifically, suicidal ideation is defined as “thinking about, considering, or planning for suicide” (Crosby et al., Reference Crosby, Ortega and Melanson2011, p. 21), suicide attempts are defined as “a non-fatal self-directed potentially injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior” (Crosby et al., Reference Crosby, Ortega and Melanson2011, p. 21), and suicide as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior” (Crosby et al., Reference Crosby, Ortega and Melanson2011, p. 21). Although suicidal ideation, attempts, and suicide are correlated, they differ significantly in etiology and prevalence, and therefore should be investigated separately. Suicidal ideation increases the likelihood of a suicide attempt, but most individuals who think about suicide do not ultimately attempt or die by suicide (Klonsky et al., Reference Klonsky, May and Saffer2016). For instance, an estimated 12.0 million adults in the United States exhibited suicidal ideation and 1.4 million attempted suicide in the year 2019 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). Thus, informed by recommendations in the suicide literature, we will be referring to suicidal thoughts and suicidal behaviors as separate but related phenomena.

Child maltreatment and suicide risk

Current state of the literature

Direct associations

There is consensus in the literature that child maltreatment experiences heighten the risk for future STBs (for a review, see Miller et al., Reference Miller, Esposito-Smythers, Weismoore and Renshaw2013). Investigators have found significant associations between childhood maltreatment and adolescent suicidal ideation (Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Woodward and Horwood2000) and attempts (Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Woodward and Horwood2000; Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Boyle, Bethell, Wekerle, Goodman, Tonmyr, Leslie, Lam and Manion2012) using both cross-sectional (Hoertel et al., Reference Hoertel, Franco, Wall, Oquendo, Wang, Limosin and Blanco2015) and prospective designs (Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Woodward and Horwood2000). These results extend to studies with young adults (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, McLaughlin, Slopen, Rosand and Smoller2013; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Cohen, Gould, Kasen, Brown and Brook2002; Puzia et al., Reference Puzia, Kraines, Liu and Kleiman2014) and adult samples (Dube et al., Reference Dube, Anda, Felitti, Chapman, Williamson and Giles2001). In a nationally representative sample of maltreated youth, researchers found that 23% of adolescents reported suicidal ideation (Coohey et al., Reference Coohey, Dirks-Bihun, Renner and Baller2014). Additionally, a study using a population-based Canadian sample found adolescents permanently removed from their homes due to maltreatment were five times more likely to present to the emergency department for STBs, compared to non-maltreated youth (Rhodes et al., Reference Rhodes, Boyle, Bethell, Wekerle, Goodman, Tonmyr, Leslie, Lam and Manion2012).

Mediators

Although the association between child maltreatment and youth STBs is well established, there is less research and subsequently less consensus on the mechanisms of this association. In other words, although we know that child maltreatment confers risk for STBs during adolescence and young adulthood, we have much to learn regarding the developmental processes that underlie this association. Thus, to inform our proposed conceptual model, we conducted a literature review on the mechanisms between child maltreatment and youth STBs (see Table 1 for a summary). This review highlights that the processes in the association between child maltreatment and youth suicide are multi-level in nature, spanning from interpersonal factors (e.g., mother-daughter relationship problems; Handley, Adams, et al., Reference Handley, Adams, Manly, Cicchetti and Toth2019) to psychological factors such as internalizing symptomology (Kwok & Gu, Reference Kwok and Gu2019; Paul & Ortin, Reference Paul and Ortin2019). In Table 1, we categorized the literature by type of mediator (i.e., biological, psychological, or interpersonal) and type of outcome (i.e., suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or a combination). It is clear from our findings that there are notable gaps in the literature. Most studies have focused on individual-level psychopathology or symptomology as mediators. Additionally, most studies use suicidal ideation as a primary outcome, and thus there is a need for more research on mediators linking child maltreatment to suicidal behavior. Additionally, there is a lack of research on biological mechanisms in the association between child maltreatment and youth suicide (as an exception, see Russell et al., Reference Russell, Heron, Gunnell, Ford, Hemani, Joinson, Moran, Relton, Suderman and Mars2019).

Table 1. Identified mediators in the association between child maltreatment and adolescent and young adult STBs

Note. Emotional abuse includes verbal abuse. Neglect includes physical and emotional neglect. Studies using ACE measures (broadly defined) not included in table.

*Studies using longitudinal or prospective designs.

a Finding was significant for boys only.

b Finding was significant for girls only.

Moderators

Similar to the literature on mediators of child maltreatment and youth suicide, moderators (e.g., risk or protective factorsFootnote 1 ) in the association between maltreatment and youth STBs range from biological to contextual factors (see Table 2). For example, individual traits such as empathy, problem-solving, and emotional competence have all been found to be protective factors in the association between child maltreatment and youth suicidal ideation in US-based and international samples (Esposito & Clum, Reference Esposito and Clum2002; Kwok et al., Reference Kwok, Yeung, Low, Lo and Tam2015; Low et al., Reference Low, Kwok, Tam, Yeung and Lo2017), while substance use problems were found to amplify this association (Miller & Esposito-Smythers, Reference Miller and Esposito-Smythers2013). At the interpersonal level, there is evidence for protective factors including social support (Esposito & Clum, Reference Esposito and Clum2002; Logan-Greene et al., Reference Logan-Greene, Tennyson, Nurius and Borja2017), school belonging (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu and Long2020), and participation in youth activities (Cero & Sifers, Reference Cero and Sifers2013). Researchers also note evidence for biological modifying factors, such as the oxytocin genotype (CD38), in the association between child maltreatment and youth STBs (Handley, Warmingham, et al., Reference Handley, Warmingham, Rogosch and Cicchetti2019). However, more research is needed to identify and replicate protective and moderating risk factors that modify the association between child maltreatment and youth STBs. Additionally, there are very few studies investigating protective factors between child maltreatment and suicidal behavior specifically.

Table 2. Identified moderators in the association between child maltreatment and adolescent and young adult STBs

Note. Emotional abuse includes verbal abuse. Neglect includes physical and emotional neglect. Studies using ACE measures (broadly defined) not included in table.

*Studies using longitudinal or prospective designs.

a This result was found among adolescents in Kenya but not in the other countries investigated (Haiti, Tanzania).

b Outcome measure was suicidal behavior, consisting of actual, attempted, and ambiguous suicide attempts and visits to the emergency room for severe suicidal ideation.

c Outcome measure was a composite of suicidal behavior, consisting of behavioral preparation for suicide attempts, efforts to avoid communication about suicide ideation, and lethality of attempt.

d The association between child maltreatment and suicide attempts was significant for females but not for males.

The literature suggests the link between child maltreatment and STBs have different etiological mechanisms for boys and girls (e.g., moderation by gender). For example, Ammerman et al. (Reference Ammerman, Serang, Jacobucci, Burke, Alloy and McCloskey2018) observed a significant association between child maltreatment and suicide attempts for girls but not boys. Similarly, Cromer et al. (Reference Cromer, Villodas and Chou2019) found that depressive symptoms mediated the association between cumulative child maltreatment exposure and suicidal ideation among girls only. Last, Barbot et al. (Reference Barbot, Eff, Weiss and McCarthy2020) found that psychosis mediated the association between emotional abuse and suicide attempts for girls only, while mood disorder symptoms mediated this association for boys only.

Current theoretical models of suicide

Research on child maltreatment and youth STBs must be guided by relevant theories in the field of suicidology. Our conceptual model of child maltreatment and youth STBs is specifically guided by the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010), due to the salience of interpersonal stressors for maltreated youth, as well as other ideation-to-action frameworks of suicide (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). The interpersonal theory of suicide proposes that individuals develop a desire for suicide through two interpersonal processes, thwarted belongingness (i.e., social isolation or lack of social connectedness) and perceived burdensomeness (i.e., the belief that one is a burden to close others, which includes aspects of self-hatred and the belief that one’s life is a liability; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010). Further, an acquired capability for suicide (i.e., learned fearlessness of death and tolerance for pain) is required for suicidal behaviors and suicide to occur. Other ideation-to-action frameworks of suicide similarly propose that the pathways leading to risk for suicidal ideation differ from those leading to suicidal behavior and suicide. For example, according to the three-step theory of suicide, psychological pain and hopelessness are critical explanatory factors for the development of suicidal ideation, while the progression from suicidal ideation to suicidal behavior is explained by one’s capacity to inflict self-injury (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). We draw from these current theories of suicide in our conceptual model by differentiating the processes leading to suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors.

In the field of suicidology, the preponderance of theoretical models are based on adult samples and lack a developmental perspective specific to youth suicide risk. Current theories in suicidology such as the ones above suggest the same set of risk and protective factors for suicide for all individuals despite their age and/or developmental stage. Some mechanisms towards suicide (e.g., depression) indeed are most likely the same for all individuals across development. However, other mechanisms and risk and protective factors are likely more salient for adolescents and young adults due to normative developmental changes and the stage-salient developmental tasks during this period. For instance, adolescent risk factors such as a lack of future orientation (i.e., having low or no expectations or goals for one’s future; Oshri, Duprey, et al., Reference Oshri, Duprey, Kogan, Carlson and Liu2018) and bullying may not be as relevant for older individuals. Adolescents are also particularly sensitive to acute stress due to normative developmental changes in biological stress response systems, and “failure” of these stress response systems have been proposed as a key risk factor for adolescent suicide (Miller & Prinstein, Reference Miller and Prinstein2019). These risk factors may be particularly salient for maltreated youth, and may moderate (i.e., exacerbate) the association between maltreatment and youth STBs. Additionally, theories in suicidology tend to be broad and do not specify the hypothesized developmental chain stemming from a triggering event, such as child maltreatment, towards youth STBs.

A developmentally informed model of child maltreatment and youth suicide will contribute to the literature by considering the unique aspects of the developmental period across multiple levels of analysis with the aim of identifying salient risk and protective factors and mechanisms. This will inform research in several ways, including but not limited to measurement (e.g., using appropriate measures for the specific developmental stage being tested), conceptualization (e.g., how concepts are operationalized and tested for adolescents compared to older adults), and study design (e.g., sampling and recruitment). Further, a developmentally informed model of suicide will contribute to applied research by providing developmentally appropriate mechanisms to target in interventions (e.g., targeting attachment processes for children or peer skills among high school students), and by emphasizing that mechanistic targets will be different and must be tuned to participants’ developmental stage. Importantly, the model we present in this paper focuses on child maltreatment as a specific precursor to suicide risk. Thus, our model is specific to maltreated youth and is intended to inform suicide prevention approaches among youth exposed to child abuse and neglect.

A developmental perspective on youth STBs

We utilize a developmental psychopathology perspective to understand and integrate the disparate literature on mechanisms and moderators in the link between child maltreatment and youth STBs, and to inform our conceptual model of the pathways from child maltreatment to youth STBs. Developmental psychopathology is an overarching framework for studying typical and atypical behavior (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1984). Several core principles of this framework shape our proposed conceptual model, including the principles of equifinality and multifinality. According to the concept of equifinality, the same outcome can be reached through multiple different developmental pathways (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch2002). For example, two adolescents who each exhibit suicidal ideation may have reached that outcome through various developmental risk processes: one may have experienced extreme early childhood neglect, resulting in an insecure attachment relationship that cascaded into mistrust of others, social isolation, and depression; the other may have experienced physical abuse that resulted in externalizing behaviors and impulsivity. These illustrative developmental pathways, although different, each may predict the emergence of STBs during adolescence. Alternatively, according to the concept of multifinality, the same or a similar set of risk factors may result in different processes and outcomes (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch2002). For example, two children who were sexually abused may show distinct outcomes by exhibiting either psychopathology or resilience in adolescence. Different risk factors (e.g., disordered neighborhoods, peer victimization) and protective factors (e.g., peer social support, emotion regulation) contribute to the process of multifinality by modifying (i.e., moderating) the outcomes stemming from child maltreatment, including the developmental processes that are implicated in the pathway from child maltreatment towards youth STBs. Additionally, risk and protective factors at different levels of the youths’ ecology may interact with one another to produce cascading transactional effects that lead to diverse outcomes.

The developmental systems perspective, which has over time been integrated into the developmental psychopathology approach, informs the concepts of multifinality and equifinality (Lerner & Castellino, Reference Lerner and Castellino2002). According to this perspective, developmental processes emerge from integrating multiple systems, both internal and external to the individual (Lerner & Castellino, Reference Lerner and Castellino2002). Here, systems are defined as “…a complex of interacting components together with the relationships among them that permit the identification of a boundary-maintaining entity or process” (Laszlo & Krippner, Reference Laszlo, Krippner and Jordan1998, p. 47). A growing child, in this perspective, is thought of as a developmental system that consists of the elements or subsystems within it (e.g., biological systems) that change over time due to the interactions among internal subsystems and with other outside systems (e.g., the family system). In our conceptual model, we draw from the transactional model of the developmental systems perspective, which posits that human development is the product of interdependent and bidirectional influences between the person and their environment (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2009). Transactions can also occur between different subsystems within the individual. For example, the development and functioning of the stress response system and the immune system may both influence one another bidirectionally over time (Oshri, Duprey, Liu & Ehrlich, Reference Oshri, Duprey, Liu and Ehrlich2020; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2009).

The proposed theoretical model was also informed by the organizational theory of development, a core tenet of the developmental psychopathology approach. According to the organizational theory, children must successfully master stage-salient developmental tasks, such as attaining secure attachment with a primary caregiver or gaining a positive self-concept and sense of mastery in early childhood (Cicchetti & Banny, Reference Cicchetti, Banny, Lewis and Rudolph2014). At each stage of development, the attainment of new developmental tasks requires reorganizing multiple systems within the individual (e.g., physiological, cognitive, and socioemotional). Successful reorganization is necessary to master subsequent tasks in the same developmental domain. Harsh, chaotic, or impoverished rearing environments can lead to failure in mastering critical developmental tasks (Cicchetti & Banny, Reference Cicchetti, Banny, Lewis and Rudolph2014). Accordingly, children who experience child maltreatment are at risk for STBs due in part to disruption in the attainment of stage-salient tasks.

The aforementioned tenets of the developmental psychopathology and developmental systems frameworks have been integrated into several existing models of youth STBs, including models on the development of borderline personality disorder and self-injurious behaviors (Crowell et al., Reference Crowell, Beauchaine, Lenzenweger, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2008; Derbridge & Beauchaine, Reference Derbridge, Beauchaine, Lewis and Rudolph2014), the developmental-transactional model of youth suicidal behavior (Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Goldstein and Brent2006), and the recent theory of adolescent suicide as a failure of physiological stress response systems (Miller & Prinstein, Reference Miller and Prinstein2019). Our model adds to this knowledge base by considering the developmental processes involved in the emergence of youth STBs specifically for maltreated youth. Additionally, our conceptual model integrates the developmental psychopathology and developmental systems frameworks with modern theories of suicide, including the interpersonal theory of suicide and other ideation-to-action frameworks of suicide, as detailed prior (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010).

A conceptual model of child maltreatment and youth suicide risk

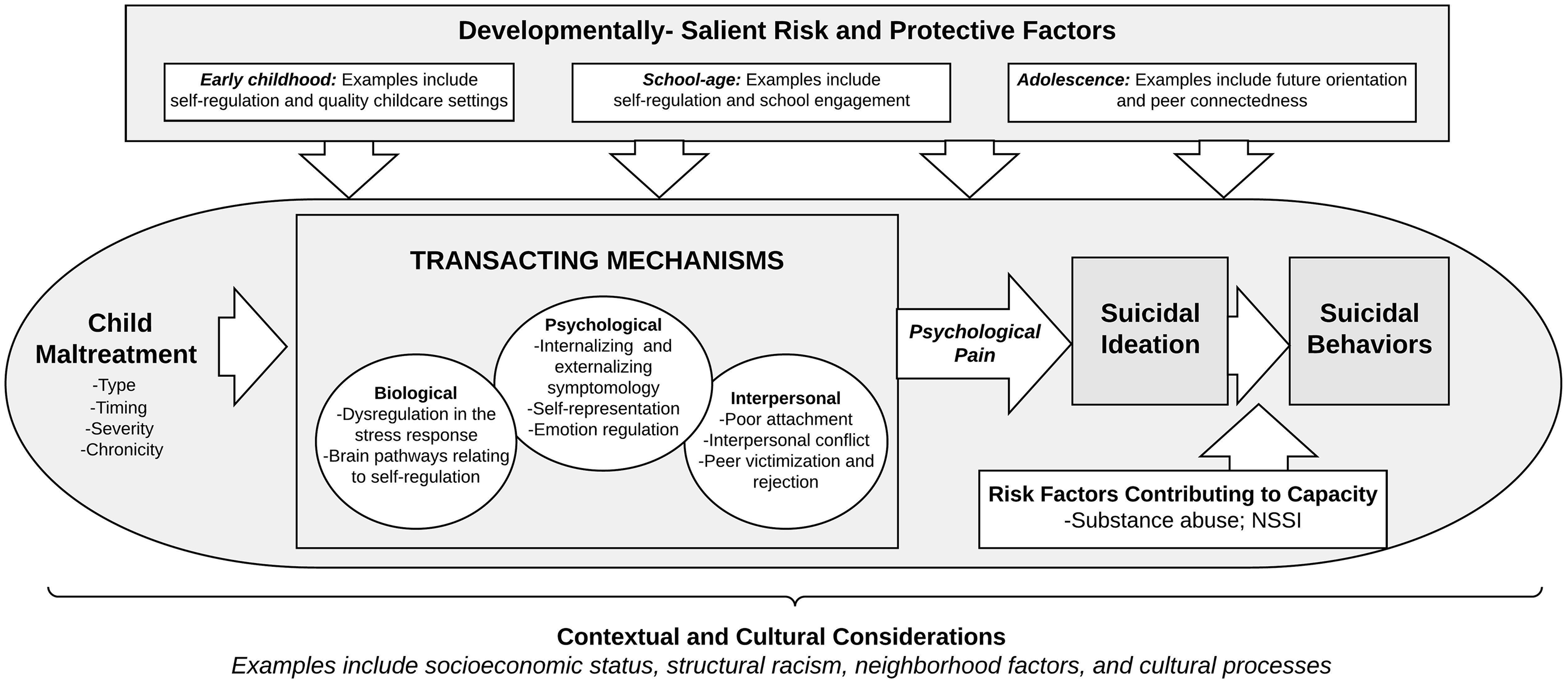

Based on the literature reviewed above, the developmental psychopathology framework, and ideation-to-action theories in suicidology, we propose a developmental model of the progression from child maltreatment to adolescent STBs (see Figure 1). There are three overarching propositions to this model. First, we suggest three primary, dynamic mechanisms at different levels of analysis (i.e., biological, psychological, and interpersonal) that link child maltreatment to the emergence of STBs in adolescence. These mechanisms are not separate processes, but instead interact with and influence one another over time. Together, in line with the three-step theory of suicide, these biological, psychological, and interpersonal processes may culminate in extreme psychological pain that can prompt youth to desire ending their lives (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015).

Figure 1. Developmental conceptual model of child maltreatment and youth suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Second, we propose developmentally salient risk factors for adolescent STBs, such as pubertal development, stressful life events, and peer problems, and protective factors such as school belonging and future orientation. Last, in line with ideation-to-action frameworks of suicide, we propose that for youth with maltreatment experiences, the progression from suicidal ideation to suicidal behaviors is exacerbated by individual vulnerabilities that may increase youths’ propensity for participating in suicidal behaviors. Such vulnerabilities include consequences of child maltreatment, such as dysregulation of the physiological stress response, substance use behaviors, and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). External factors associated with child maltreatment, such as recent stressful life events, may also exacerbate the pathway from suicidal ideation to suicidal behaviors. This third aspect of our model, which explains the transition from suicidal ideation to behaviors, differentiates our model from other etiological theories for related psychopathology outcomes.

Together, our model proposes a set of risk factors and a set of hypothesized relations between these risk factors. Consistent with the concept of multifinality, many of our proposed risk factors (e.g., child maltreatment exposure, interpersonal risk factors, and psychopathology) are general-risk factors that are associated not only with STBs but other adverse outcomes such as substance use disorders or NSSI. However, several aspects of our model are specific to STBs. For instance, psychological pain (i.e., psychache or mental pain) is a suicide-specific risk factor that we propose results from several multi-level transacting developmental mechanisms. A recent systematic review revealed that mental pain is a predictor of suicide risk both within clinical samples of adolescents and adults and within non-clinical samples (Verrocchio et al., Reference Verrocchio, Carrozzino, Marchetti, Andreasson, Fulcheri and Bech2016). Additionally, we propose several suicide-specific risk factors that are involved in the progression from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts. Thus, the following model of child maltreatment and youth STBs is specific to the goal of understanding the development of youth STBs, and can be used to guide suicide-specific prevention interventions.

Considering the dimensionality of child maltreatment

Our model considers the complex and multidimensional nature of child maltreatment experiences and how this influences developmental trajectories towards suicide risk. Child maltreatment can be measured along several dimensions including type, severity, developmental timing (i.e., the age or developmental stage at which maltreatment occurs), relationship with the perpetrator (i.e., familial versus non-familial), and chronicity (i.e., whether maltreatment occurs once or is a recurring event throughout childhood; English et al., Reference English, Upadhyaya, Litrownik, Marshall, Runyan, Graham and Dubowitz2005; Manly et al., Reference Manly, Kim, Rogosch and Cicchetti2001). Accounting for the dimensionality of child maltreatment is important not only for ecologically valid measurement, but also per the developmental psychopathology theoretical framework. Different dimensions of child maltreatment represent distinct experiences children may have in their rearing environment. Consequently, the complexity in child maltreatment experiences contributes to the multifinality in youth developmental outcomes. This complexity is particularly important to consider in our model of child maltreatment and youth STBs, as different dimensions of child maltreatment experiences can differentially impact the developmental mechanisms that are most salient in the pathway to youth STBs. Additionally, the dimensionality of child maltreatment has implications for the way maltreatment is operationalized and modeled. For instance, within samples of maltreated youth, dimensions of maltreatment such as severity or perpetrator type may moderate the association between maltreatment exposure and youth STBs.

Developmental timing and chronicity of maltreatment are critical to consider in the context of youth STBs. According to the organizational theory of development, maltreatment will impact the stage-salient developmental tasks that correspond to the developmental stage of the child when maltreatment occurs. Consequently, which developmental tasks are disrupted will impact children’s and adolescents’ developmental trajectories and the possible emergence of psychopathology. For instance, maltreatment during infancy may reasonably disrupt the attainment of a secure attachment relationship with a primary caregiver (Stronach et al., Reference Stronach, Toth, Rogosch, Oshri, Manly and Cicchetti2011). In contrast, maltreatment that occurs during adolescence may disrupt salient milestones such as identity development. Likewise, maltreatment is often chronic throughout childhood and adolescence (Warmingham et al., Reference Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch, Manly and Cicchetti2019), and this chronicity can influence the developmental pathways to youth suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Chronic childhood maltreatment that occurs in several developmental stages may upend the attainment of multiple stage-salient developmental tasks, compounding the risk for subsequent psychopathology outcomes, including STBs. Several studies have indeed investigated maltreatment timing and chronicity in relation to subsequent suicidal thoughts and behaviors during adolescence. In the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, adolescents who were first exposed to physical abuse in preschool (i.e., ages 3–5) or in adolescence (i.e., ages 11–17), and adolescents who were first exposed to sexual abuse in preschool, had a heightened risk for suicidal ideation (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, McLaughlin, Slopen, Rosand and Smoller2013). Further, emerging adults who first experienced maltreatment during infancy were more likely to exhibit suicidal ideation compared to those who first experienced maltreatment in later childhood (Handley, Warmingham, et al., Reference Handley, Warmingham, Rogosch and Cicchetti2019).

The developmental timing and chronicity of child maltreatment are also pertinent to the onset and timing of youth STBs. In a cross-national study, a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse increased the odds of a suicide attempt in childhood (i.e., ages 4–12) by 6–10-fold, respectively (Bruffaerts et al., Reference Bruffaerts, Demyttenaere, Borges, Haro, Chiu, Hwang, Karam, Kessler, Sampson, Alonso, Andrade, Angermeyer, Benjet, Bromet, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Florescu, Gureje, Horiguchi and Nock2010). The same study showed that childhood abuse had a smaller but still significant impact on the onset of suicidal behavior in young adulthood and adulthood (OR range: 2.5–3.1). However, child maltreatment was assessed retrospectively, and thus it is unclear whether timing of childhood sexual and physical abuse played a role in the onset and timing of suicidal behavior. Theoretically, the timing of child maltreatment may be related to both the onset of youth STBs and the mechanisms relevant to this onset. Childhood maltreatment that is chronic throughout both childhood and adolescence may reasonably be related to an earlier onset of STBs that occurs concurrently with the abuse. However, more research is needed to assess how timing and chronicity of child maltreatment is related with timing (e.g., onset and persistence) of youth STBs.

Different subtypes of maltreatment may also impact unique developmental processes that serve as mechanisms linking maltreatment to subsequent STBs. There is indeed evidence for the impact of maltreatment type on eventual STB outcomes. For example, a recent meta-analysis showed differential associations between child maltreatment type and risk for suicidal behavior among young people. Findings showed that sexual abuse contributed to a 3.41-fold increase in odds of suicidal behavior, while physical neglect contributed to a 1.79-fold increase in odds of suicidal behavior (Angelakis et al., Reference Angelakis, Austin and Gooding2020). Relatedly, recent perspectives on childhood adversity posit that threat (e.g., physical abuse) and deprivation (e.g., neglect) are unique aspects of adversity with specific mechanisms towards adverse outcomes (McLaughlin & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan2016). For instance, disruptions to emotional processing are hypothesized to be a primary mechanism linking experiences of threat to adverse psychopathology outcomes (McLaughlin & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan2016). Further research is needed that incorporates dimensional models of childhood maltreatment with respect to the development of STBs.

Recent studies have also demonstrated the complexity in child maltreatment experiences, and the common co-occurrence of types, by using person-centered approaches. For example, among a sample of child protective services (CPS) involved children, latent classes of child maltreatment experiences (e.g., type, chronicity) predicted different child functioning outcomes. The majority of children in this study were characterized as having chronic and multi-subtype maltreatment, and subsequently had the highest risk for emotional and behavioral problems (Warmingham et al., Reference Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch, Manly and Cicchetti2019). Future research is needed to uncover how the complexity in child maltreatment experiences relates to risk for youth STBs, and to better understand the developmental pathways in these associations.

Biological, psychological, and interpersonal mediating processes

Following a developmental psychopathology approach, our model of youth STBs proposes three critical developmental processes at three levels of analysis (biological, psychological, and interpersonal). These processes include physiological dysregulation, disruptions in emotion regulation, and risky interpersonal and family processes (see Figure 1). Importantly, informed by the developmental systems perspective, these three mediating processes are not discrete, but instead transact with one another over time to influence the emergence of STBs. For example, physiological dysregulation can underlie or exacerbate psychopathology while also contributing to stressful family contexts. There is also evidence that youth psychopathology and family stress transact with and exacerbate one another (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Doan and Tompson2014). A child’s disruptive or internalizing behavior can cause conflict within the family system, which may prolong or exacerbate the internalizing or externalizing behaviors of the child. Together, these risky processes may result in the psychological pain that theoretically precedes suicidal behavior (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). Below, we outline the specific developmental mechanisms we propose in the pathway from child maltreatment experiences to youth STBs.

Biological processes

Experiences of early life stress, including childhood maltreatment, are known to negatively impact the development of various bio-regulatory systems within the individual (Lovallo, Reference Lovallo2013; Obradović, Reference Obradović2012; Wismer Fries et al., Reference Wismer Fries, Shirtcliff and Pollak2008). Thus, at the biological level, we propose that child maltreatment impacts neurobiological and physiological systems of self-regulation, which in turn can transact with other proposed mechanisms (e.g., internalizing psychopathology and interpersonal problems), leading to the psychological pain that is the theoretical root cause for STBs (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). Specifically, we propose that child maltreatment impacts risk for youth STBs via (a) dysregulation of psychophysiological stress response systems, and relatedly, (b) neurobiological mechanisms associated with self-regulation.

Stress response systems

There is a consensus through psychophysiological, genetic, and neuropsychological (e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)) studies that childhood adversity such as child maltreatment can impact multiple biological systems involved in the stress response. This includes the two primary stress response systems, the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Gunnar & Quevedo, Reference Gunnar and Quevedo2007). The autonomic system consists of the sympathetic nervous system, which responds to external demands with immediate fight or flight reactions, and the parasympathetic nervous system, which works to regulate the individual and maintain homeostasis (Gunnar & Quevedo, Reference Gunnar and Quevedo2007). The autonomic nervous system transacts with the HPA axis, which mediates the individual response to stressors by facilitating the secretion and action of glucocorticoids (i.e., cortisol) throughout the body (Tarullo & Gunnar, Reference Tarullo and Gunnar2006). Glucocorticoids have a variety of actions in the body, including suppressing the immune and inflammatory response (Irwin & Cole, Reference Irwin and Cole2011), regulating energy via glucose metabolism, and inhibiting the short-term fight or flight response (Gunnar & Quevedo, Reference Gunnar and Quevedo2007).

According to the adaptive calibration model, an evolutionary-developmental theory, early life experiences shape the development of stress response systems (del Giudice et al., Reference del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011). Specifically, inputs from the physical environment modify physiological systems, including the autonomic nervous system and HPA axis, to facilitate adaptation to the current environment (Frankenhuis et al., Reference Frankenhuis, Young and Ellis2020). For example, it is possible that young children exposed to physical abuse will become hyper-responsive to stress to facilitate their survival in this type of threatening environment. However, adaptive strategies that include hyper- or hypo-stress-responsiveness can lead to maladaptation later in life when the individual is no longer in the threatening or adverse environment.

There is a robust research literature linking early life stress, and specifically child maltreatment, to physiological dysregulation in stress response systems (Obradović, Reference Obradović2012). For example, several research groups have investigated the impact of early life stress by utilizing samples of chronically deprived children from orphanages in Romania (Gunnar et al., Reference Gunnar, Morison, Chisholm and Schuder2001; Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Guyon-Harris, Tibu, Wade, Nelson, Fox and Zeanah2020). Children who spent most of their childhood in these institutions were found to have heightened salivary cortisol levels (a marker of dysregulated HPA axis function), as compared to children who were not raised in institutions and children who were adopted early in life (Gunnar et al., Reference Gunnar, Morison, Chisholm and Schuder2001). In US-based samples, experiences of childhood maltreatment have also been found to impact diurnal patterns of cortisol (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Butzin-Dozier, Rittenhouse and Dozier2010), as well as cortisol reactivity (Harkness et al., Reference Harkness, Stewart and Wynne-Edwards2011), although this literature is mixed. There is also literature documenting the associations between child maltreatment and activity in the autonomic nervous system (Huffman et al., Reference Huffman, Oshri and Caughy2020). For example, adolescents who reported experiences of childhood maltreatment were more likely to have a heightened sympathetic nervous system response to a common psychosocial stress task, as compared to non-maltreated adolescents (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Alves and Mendes2014). Early life adversities such as child maltreatment confer risk for methylation and other epigenetic changes in genes relating to HPA function (Cicchetti et al., Reference Cicchetti, Hetzel, Rogosch, Handley and Toth2016), suggesting that epigenetic modifications in genes relating to the stress response may serve as an underlying mechanism between child maltreatment and suicide. However, most epigenetic studies have used clinical adult samples, and thus additional research is needed on how child maltreatment influences youth STBs via epigenetic mechanisms, and how this relates to stress response reactivity.

Dysregulation in physiological stress response systems may serve as a critical and developmentally salient risk factor for suicide among adolescents (Miller & Prinstein, Reference Miller and Prinstein2019). Moreover, an abnormal response to stress in the HPA axis has been posited as a risk factor for suicidal behavior in part due to associated behaviors such as impaired decision making and aggression (Steinberg & Mann, Reference Steinberg and Mann2020). There is some empirical evidence to support these suggestions. For example, heightened reactivity in the HPA axis in response to a laboratory-administered psychosocial stress task was related to suicidal ideation three months later in a sample of adolescent girls at risk for suicidal behaviors (Giletta et al., Reference Giletta, Calhoun, Hastings, Rudolph, Nock and Prinstein2015). Alterations in the autonomic nervous system have also been observed in relation to STBs. Women with a history of suicide attempts had lower basal high-frequency heart rate variability, a measure of parasympathetic nervous system capacity, as compared to women without a history of suicide attempt (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Chesin, Fertuck, Keilp, Brodsky, Mann, Ceren, Benjamin-phillips and Stanley2016). This finding indicates that a lesser capacity of the parasympathetic nervous system, or a dampened ability to regulate oneself, may be linked with suicide-related behaviors.

It is important to note that early life stress such as child maltreatment can produce both dampened responsiveness (hypo-responsivity; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Cui, Duprey, Kogan and Oshri2020; Lovallo, Reference Lovallo2013) as well as heightened responsiveness (hyper-responsivity; e.g., Harkness et al., Reference Harkness, Stewart and Wynne-Edwards2011) in stress response systems. It is possible that the type and timing of stressor experienced, genetic and temperamental differences, and the developmental stage of the child impacts whether youth exhibit hypo- or hyper-reactivity to stress (Bosch et al., Reference Bosch, Riese, Reijneveld, Bakker, Verhulst, Ormel and Oldehinkel2012; Cicchetti et al., Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch, Gunnar and Toth2010; Obradović, Reference Obradović2012). Indeed, the stress response system exhibits marked plasticity and adapts dynamically to changing environmental circumstances such as stressful rearing contexts. For example, there is some evidence that the stress response system is initially hyper-active after a child experiences toxic stressors such as child maltreatment, and then eventually becomes suppressed due to habituation of the stress response (Trickett et al., Reference Trickett, Noll, Susman, Shenk and Putnam2010). Additionally, some research suggests that child psychopathology might moderate the association between child maltreatment and cortisol regulation (Cicchetti et al., Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch, Gunnar and Toth2010). However, more research is needed to investigate the complex relationships between early life stress experiences and dysregulation of physiological stress response systems. Thus, our proposed model suggests that dysregulation in stress response systems, including both dampened and heightened responsiveness, can serve as a mechanism between child maltreatment and youth STBs.

Neurobiological pathways relating to self-regulation

We also propose that neurobiological changes to brain pathways relating to self-regulation may underlie the association between child maltreatment experiences and youth STBs. Although we discuss these mechanisms here separately, these neurobiological mechanisms are related to the aforementioned psychophysiological stress response mechanisms. Below we discuss several findings relevant to a neurobiological pathway related to self-regulation; however, an exhaustive review of the brain mechanisms related to child maltreatment and youth suicide are outside the scope of the present article.

Experiences of early life stress, including child maltreatment, may impede normative and healthy brain development (Berens et al., Reference Berens, Jensen and Nelson2017; Twardosz & Lutzker, Reference Twardosz and Lutzker2010). The developing brain shows marked plasticity throughout childhood and adolescence, and consequently, traumatic environmental experiences such as maltreatment can influence both the structure and function of certain brain areas and networks (Twardosz & Lutzker, Reference Twardosz and Lutzker2010). Child maltreatment is known to impact brain areas that are implicated in heightened emotional reactivity and increased salience of threatening stimuli, both of which are common for individuals exposed to childhood trauma, and which have been suggested as behavioral mechanisms linking child maltreatment to future psychopathology (McLaughlin & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin and Lambert2017). Indeed, structural and functional differences have been found among maltreated children and adults in areas relating to emotion processing and emotion regulation (e.g., limbic and frontal brain regions; Hallowell et al., Reference Hallowell, Oshri, Liebel, Liu, Duda, Clark and Sweet2019; Oshri et al., Reference Oshri, Gray, Owens, Liu, Duprey, Sweet and MacKillop2019). For example, children and adults who have prior experiences of child maltreatment are more likely to exhibit increased activation in the amygdala in response to an fMRI task with emotional stimuli (Hein & Monk, Reference Hein and Monk2017; Tottenham et al., Reference Tottenham, Hare, Millner, Gilhooly, Zevin and Casey2011). Functional changes in relevant frontal cortex areas may also underlie emotion regulation difficulties among maltreated children and adolescents (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves and Sheridan2015; Pechtel & Pizzagalli, Reference Pechtel and Pizzagalli2011).

Neurobiological deficits in emotion regulation and reactivity have also been implicated in suicidal ideation and behaviors (Li et al., Reference Li, Chen, Gong and Jia2020; Pan et al., Reference Pan, Hassel, Segreti, Nau, Brent and Phillips2013). For instance, a meta-analysis comparing findings from task-based fMRI studies found that adult patients with major depressive disorder and history of a suicide attempt, compared to major depressive disorder patients without a history of attempt, showed functional changes in brain areas relevant to emotion regulation and processing, including the insula and fusiform gyrus (Li et al., Reference Li, Chen, Gong and Jia2020). In another study, adolescents with a history of suicide attempts evinced significantly different activation patterns of several brain areas in response to an emotion-processing paradigm, in comparison to a group of adolescents with depression but no history of suicide attempts and to a healthy control group (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Hassel, Segreti, Nau, Brent and Phillips2013). Specifically, adolescent suicide attempters presented a heightened response to angry faces in sensory cortical areas and areas associated with attention processing. Thus, although no studies to our knowledge have used formal mediation analysis to examine brain pathways as mechanisms between child maltreatment and youth STBs, it is evident that neurobiological pathways implicated in emotion regulation can influence the risk for STBs among youth with exposure to child maltreatment. Specifically, these neurobiological findings may reflect an individuals’ inability to adaptively cope with stressful or emotional experiences, which in turn can lead to excessive or prolonged negative mood states (i.e., psychological pain) and subsequent suicidal ideation (Van Heeringen & Mann, Reference Van Heeringen and Mann2014).

Psychological processes

The second proposed mechanism linking early life stress with adolescent suicide-related behaviors is through psychological processes, including emotion regulation, self-representation, and internalizing and externalizing symptomology. In accordance with the organizational perspective on development, a key tenet of the developmental psychopathology perspective, adverse rearing environments can disrupt stage-salient tasks relating to children’s socioemotional development, such as self-concept development and emotion regulation (Cicchetti & Banny, Reference Cicchetti, Banny, Lewis and Rudolph2014). For example, opinions and actions of caregivers toward the child contribute to the child’s own perceived worth (Harter, Reference Harter and Cicchetti2016). Consequently, a child in an insecure or abusive rearing environment may grow to make negative attributions about oneself which are associated with concurrent or subsequent internalizing symptoms such as anxiety and depression (Harter, Reference Harter and Cicchetti2016). Further, child maltreatment can disrupt the attainment of self-regulation abilities, including emotion regulation and self-system processes, cascading into externalizing behaviors such as disruptiveness and impulsiveness (Kim & Cicchetti, Reference Kim and Cicchetti2009). These disruptions in stage-salient developmental tasks prompted by maltreatment can subsequently lead to increased risk for STBs during adolescence and emerging adulthood.

Emotion regulation

Children and adolescents who have been exposed to child maltreatment are more likely than non-abused peers to have problems with emotion regulation, including having less access to emotion regulation strategies and greater emotion reactivity (Kim-Spoon et al., Reference Kim-Spoon, Cicchetti and Rogosch2013). For instance, children aged 6–12 who were exposed to child maltreatment, measured prospectively, were more likely to exhibit emotion regulation problems such as low emotional awareness and inappropriate emotional displays (Kim & Cicchetti, Reference Kim and Cicchetti2009). In a recent meta-analysis, child maltreatment was significantly associated with emotion dysregulation (Lavi et al., Reference Lavi, Katz, Ozer and Gross2019). The biological underpinnings of emotion regulation, including the neurological processes involved in emotion processing and the physiological processes relating to the acute stress response, have also been associated with child maltreatment (Koss & Gunnar, Reference Koss and Gunnar2018; Twardosz & Lutzker, Reference Twardosz and Lutzker2010).

Adolescents and young adults who have problems regulating and coping with difficult emotions may think about suicide and act upon self-injurious thoughts to escape from their psychological pain. Indeed, in a sample of adolescent inpatients, youth who had impulse control difficulties and who lacked sufficient access to emotion regulation strategies were more likely to have past-year suicidal ideation, even when controlling for mood, anxiety, and behavioral disorders (Hatkevich et al., Reference Hatkevich, Penner and Sharp2019). In another study using a sample of high school students in rural, low-income communities, teens who reported having limited access to emotion regulation strategies were more likely to also report a suicide attempt (Pisani et al., Reference Pisani, Wyman, Petrova, Schmeelk-Cone, Goldston, Xia and Gould2013). Relatedly, a recent cross-sectional study found evidence for emotion dysregulation as a mediator between child maltreatment and adolescent self-harm (Peh et al., Reference Peh, Shahwan, Fauziana, Mahesh, Sambasivam, Zhang, Ong, Chong and Subramaniam2017). Thus, sufficient evidence exists to encourage further investigations of emotion regulation (including emotion regulation strategies and emotion reactivity) as a mediator between child maltreatment and youth STBs.

Self-representation

The availability of sensitive and stable caregivers is crucial to the normative development of self-representation throughout childhood (Harter, Reference Harter, Damon and Lerner2006). Theoretically, having a secure attachment relationship gives children a solid foundation for healthy development, including the development of a positive self-concept. Experiences of abuse may trigger youth to incorporate negative feedback from caregivers (e.g., connotations of being “bad”) into their own self-concept. Studies show that youth who have been abused or neglected by their caregivers have lower self-esteem compared to their non-maltreated peers (Kim & Cicchetti, Reference Kim and Cicchetti2006; Shen, Reference Shen2009). In a story-telling task, the narratives of maltreated preschoolers were more likely to contain negative self-representations compared to the narratives of their non-maltreated counterparts (Toth et al., Reference Toth, Cicchetti, MacFie, Maughan and Vanmeenen2000).

Several studies provide support for the role of self-representation in the developmental pathway from child maltreatment to youth STBs. In a sample of adolescents living in rural China, those who had experienced neglect and emotional abuse were more likely to report suicidal ideation, and this was mediated by a lack of self-compassion (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu and Long2020). There is also evidence for the role of self-representation, including self-esteem and self-criticism, in the association between child maltreatment and suicidal behaviors (Cero & Sifers, Reference Cero and Sifers2013; Falgares et al., Reference Falgares, Marchetti, Manna, Musso, Oasi, Kopala-Sibley, de Santis and Verrocchio2018). For instance, in a sample of undergraduate students in Italy, self-criticism partially mediated the association between retrospectively reported experiences of child maltreatment and an index measuring the propensity for suicide (Falgares et al., Reference Falgares, Marchetti, Manna, Musso, Oasi, Kopala-Sibley, de Santis and Verrocchio2018). It is possible that these self-processes are underlying behavioral symptomology, including internalizing and externalizing symptoms, in the psychological developmental pathways from child maltreatment to youth STBs.

Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology

There is much empirical research that has linked child maltreatment with mental illness and symptoms of psychopathology during adolescence. Abuse or neglect during childhood predicts heightened internalizing symptoms in longitudinal studies (Bolger & Patterson, Reference Bolger and Patterson2001; Duprey et al., Reference Duprey, Oshri and Caughy2017; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Kotch, Wiley, Litrownik, English, Thompson, Zolotor, Block and Dubowitz2011). For example, findings from the longitudinal Isle of Wight study indicated that youth who were maltreated were 15.5 times more likely to experience minor depression and 8.11 times more likely to experience an anxiety disorder, compared to non-abused youth (Collishaw et al., Reference Collishaw, Pickles, Messer, Rutter, Shearer and Maughan2007). Internalizing symptomology, in turn, is a strong predictor of suicide-related behaviors during adolescence and emerging adulthood (Bridge et al., Reference Bridge, Goldstein and Brent2006).

It is also likely that, for some youth, externalizing psychopathology (e.g., disruptiveness and impulsivity) plays a role in the connection between child maltreatment and youth STBs. Child maltreatment is a robust predictor of externalizing disorders throughout childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood (Oshri et al., Reference Oshri, Rogosch, Burnette and Cicchetti2011; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, English and White2016). In turn, recent studies have shown that externalizing disorders are a direct risk factor for suicide-related behaviors. For example, in a clinical sample of psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents, 67.9% of those who had attempted suicide multiple times were diagnosed with an externalizing disorder (e.g., disruptive behavior disorders, substance use disorders; D’Eramo et al., Reference D’Eramo, Prinstein, Freeman, Grapentine and Spirito2004). In fact, scholars have recently posited that impulsivity may serve as a primary mechanism linking childhood maltreatment with suicide (Braquehais et al., Reference Braquehais, Oquendo, Baca-García and Sher2010).

Most investigations on mechanisms between child maltreatment and youth STBs have focused on individual symptomology, including internalizing and externalizing-related symptoms. Not surprisingly, internalizing problems (including depression and depressive symptoms) were found as a mediator between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation in numerous studies (Cromer et al., Reference Cromer, Villodas and Chou2019; Handley, Adams, et al., Reference Handley, Adams, Manly, Cicchetti and Toth2019; Sekowski et al., Reference Sekowski, Gambin, Cudo, Wozniak-Prus, Penner, Fonagy and Sharp2020; Wan & Leung, Reference Wan and Leung2010). There is also evidence for other related mediators, including psychache (i.e., psychological pain; Li et al., Reference Li, You, Ren, Zhou, Sun, Liu and Leung2019), negative emotionality (Cho & Glassner, Reference Cho and Glassner2020), and recent psychological distress (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Proctor, English, Dubowitz, Narasimhan and Everson2012). Similar mediating mechanisms have been found in the association between child maltreatment and suicide attempts. For instance, depressed mood was found as a mediator between both sexual abuse and family conflict and adolescent suicide attempts (Sigfusdottir et al., Reference Sigfusdottir, Asgeirsdottir, Gudjonsson and Sigurdsson2013). There are considerably fewer studies investigating externalizing behaviors in the pathway from child maltreatment to youth STBs, but some evidence exists. For instance, externalizing problems mediated the association between childhood physical abuse and youth suicidal ideation in a large sample of Chinese high school students (Wan & Leung, Reference Wan and Leung2010).

Taken together, there is strong evidence that various forms and symptoms of psychopathology play a role in the developmental pathway between child maltreatment and adolescent STBs. It is possible that more generalized forms of psychopathology, as opposed to specific diagnoses, are mechanisms in this link. Recent models suggest that a higher-order, p factor, of general psychopathology underlies traditional psychiatric diagnoses such as in the DSM and includes diagnoses on both the internalizing and externalizing spectrum (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014). This model on the structure of psychopathology can also explain the high rates of comorbidity that exist between internalizing and externalizing disorders (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014). To our knowledge, just one study has specifically investigated comorbidity between externalizing and internalizing symptomology as a mechanism between childhood maltreatment and adolescent STBs (Duprey et al., Reference Duprey, Oshri and Liu2019b). Theoretically, the combination of internally focused symptoms like depression and anxiety with externally focused symptoms like substance use, impulsivity, and deviance might exacerbate vulnerability for risk behaviors such as suicidal thoughts and behaviors during adolescence. Thus, given the high rates of comorbidity between symptoms and disorders on the internalizing and externalizing psychopathology spectrums, and newer models on the structure of psychopathology, future research should investigate psychopathology comorbidity as a mediator in the link between child maltreatment and youth STBs.

Interpersonal and family processes

The third broad transactional mechanism that we propose is risky family and interpersonal processes (Repetti et al., Reference Repetti, Taylor and Seeman2002), and more specifically, attachment processes, family conflict, and peer problems. As with other aspects of our model, these proposed mechanisms are informed by prior literature and developmental psychopathology theory. Additionally, the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010) guides the proposed interpersonal mechanisms linking child maltreatment to youth STBs. The interpersonal theory of suicide posits that interpersonal risk factors (particularly, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) lead to the emergence of STBs (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness may result from youth’s interpersonal interactions with their families and peers. In the family context, youth who grow up in abusive households may develop feelings of both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness due to a lack of connectedness to their family unit, and/or a self-hatred that might stem from emotional abuse or other forms of maltreatment. Indeed, experiences of childhood emotional abuse predicted both thwarted belongingness and perceive burdensomeness (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Monteith, Rozek and Meuret2018), and perceived burdensomeness was found to mediate the association between childhood experiences of emotional abuse and young adult suicidal ideation (Puzia et al., Reference Puzia, Kraines, Liu and Kleiman2014).

Attachment

In accordance with a developmental psychopathology framework, children who are maltreated may develop insecure attachment relationships with their caregivers (Stronach et al., Reference Stronach, Toth, Rogosch, Oshri, Manly and Cicchetti2011), and these poor attachment relationships can cascade into future adverse outcomes, including psychopathology (Hankin, Reference Hankin2005). As noted prior, theories of attachment and developmental psychopathology suggest that a secure attachment relationship with one’s caregiver is a foundation on which subsequent healthy development can build upon (Sroufe et al., Reference Sroufe, Carlson, Levy and Egeland1999). Insecure attachment may initiate a cascade of developmental maladaptation, and together these early experiences and developmental perturbations may probabilistically result in future psychopathology including suicide risk. Accordingly, attachment processes are deeply interconnected with the other developmental mechanisms named in our model such as emotion regulation, self-representation, and behavioral problems. For instance, a maltreated child with an insecure attachment relationship with their caregiver may develop negative self-representations and poor self-esteem, which paired with a consistent negative home environment, can trigger depressive symptomology and suicide risk during adolescence.

Family conflict

Youth who lack secure attachment to a primary caregiver may also later develop relationships with that caregiver characterized by conflict and insecurity (Aikins et al., Reference Aikins, Howes and Hamilton2009). Family conflict is a major source of stress and psychological pain for adolescents and may precede suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Pelkonen et al., Reference Pelkonen, Karlsson and Marttunen2011). Thus, we propose that conflict with family members is a key mechanism linking child maltreatment to future STBs. Theoretically, conflict with family members can predispose youth to feeling burdensome and lacking belonging to a central family unit, and this burdensomeness and thwarted belonging may cause STBs to emerge. Indeed, there is empirical support for the role of family conflict as a mediator between child maltreatment and youth suicidal ideation. Within a sample of depressed low-socioeconomic status adolescent girls, Handley, Adams, et al. (Reference Handley, Adams, Manly, Cicchetti and Toth2019) tested three competing mediators (i.e., mother-adolescent conflict, mother-adolescent relationship quality, and depressive symptoms) and found evidence for mother-daughter relationship quality and depressive symptoms as mediators in the association between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation. Similarly, poor family relationships (operationalized as lower levels of cohesion and expressiveness, and higher levels of conflict) mediated the association between physical abuse and suicidal ideation in a large sample of Chinese high school students (Wan & Leung, Reference Wan and Leung2010).

Peer problems

Child maltreatment experiences increase the risk for bullying victimization and peer rejection in childhood and adolescence (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Espelage, Grogan-Kaylor and Allen-Meares2012). Similar to family conflict, youth who experience peer victimization or rejection may lack feelings of belonging, which can predispose them to engage in suicidal thinking. Indeed, there is a large body of evidence showing that adolescents who are bullied by their peers (in person or via cyberbullying) are more likely to engage in suicidal thinking and suicide attempts (Hinduja & Patchin, Reference Hinduja and Patchin2010). A recent meta-analysis found that bullying victimization and perpetration were both significantly associated with a greater odds of suicidal ideation and behaviors, with odds ratios ranging from 2.12 to 4.02 (Holt et al., Reference Holt, Vivolo-Kantor, Polanin, Holland, DeGue, Matjasko, Wolfe and Reid2015). Certain groups of youth, particularly those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ), are subject to increased levels of bullying and discrimination from peers that can put them at an increased risk of suicide (Ybarra et al., Reference Ybarra, Mitchell, Kosciw and Korchmaros2015).

Taken together, there is convincing theoretical and empirical support that interpersonal processes play a unique role in the developmental pathway from child maltreatment experiences to the emergence of STBs in adolescence and young adulthood. However, more research is needed to replicate prior findings and investigate specific interpersonal processes in the pathway from child maltreatment to youth STBs. For example, disruption in attachment processes is a candidate mechanism that is associated with child maltreatment and poor mental health outcomes (Hankin, Reference Hankin2005; Stronach et al., Reference Stronach, Toth, Rogosch, Oshri, Manly and Cicchetti2011), but has not been investigated specifically in relation to youth STBs. Additionally, most studies investigating interpersonal processes in the association between child maltreatment and youth STBs examined suicidal ideation as an outcome variable. It will be important for future research to examine the role of interpersonal processes, both within and outside of the family, as precursors to youth suicidal behaviors and suicide.

Developmentally salient risk and protective factors

In our model, we specify the role of developmentally salient risk and protective factors that can buffer youth from the harm posed by exposure to child maltreatment. According to the developmental psychopathology approach and the concept of multifinality, the emergence of youth STBs is one of many possible outcomes stemming from exposure to child maltreatment. Importantly, many youth who experience child maltreatment along with its various adverse outcomes (e.g., internalizing psychopathology or family-child conflict) do not end up exhibiting suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescence nor later in life. Protective factors are moderators that can buffer, or lessen, the impact of child maltreatment exposure on the likelihood of developing suicidal thinking or behaviors (Rutter, Reference Rutter1985), while moderating risk factors can exacerbate the impact of child maltreatment on youth STBs.

In line with a developmental perspective on youth STBs, it is important to consider that both protective and risk (i.e., exacerbating) factors can affect suicidal ideation and behaviors differently depending on the time in a child’s development. In Figure 1, we give examples of empirically supported risk and protective factors for maltreated children and adolescents at different stages of development (i.e., early childhood, school age, and adolescence). For example, school belonging and participation in youth activities were found to be protective in the association between physical abuse and suicidal ideation and attempts among adolescents (Cero & Sifers, Reference Cero and Sifers2013; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Liu and Long2020). These protective factors are salient to the developmental stage of adolescence, which is characterized by rapid social development and the growing importance of peer groups.

Our conceptual model also posits that there are developmentally salient moderating risk factors that can exacerbate the pathway from child maltreatment to youth STBs. Adolescence marks an extended transition between childhood and young adulthood, and includes biological shifts such as puberty, as well as personality and social shifts including identity development and the increased salience of peers. During this time, certain developmental transitions and risk factors (both direct and moderating) may exacerbate the pathway towards suicidal ideation, and between suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors. Therefore, in this model, the transactions between vulnerability factors that may have been continuous throughout childhood (i.e., physiological dysregulation, psychopathology, and interpersonal problems), coupled with the challenges of adolescence, can result in the emergence of STBs. For example, stressful life events exacerbated the association between child maltreatment and suicidal ideation in a sample of adolescent girls (Duprey et al., Reference Duprey, Handley, Manly, Cicchetti and Toth2021). Other possible developmentally salient risk factors to consider by future research include, but are not limited to, pubertal development, risky sexual behaviors, and peer victimization.

Progression from suicidal ideation to suicidal behaviors

Our conceptual model is informed by ideation to action theories of suicide, such as the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010) and the three-step theory (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015), which posit that different risk factors and processes characterize the development of suicidal thoughts versus those that characterize the progression from suicidal thoughts towards suicidal behaviors. We integrate these theories of suicidology (which are based on adult models) with a developmental psychopathology lens to apply them to the emergence of STBs in adolescence and emerging adulthood. According to these frameworks, the progression from suicidal ideation to suicide behaviors (i.e., attempts) is driven by capability (defined as an individual’s capacity to engage in self-harming behaviors). For most people, including those who may have suicidal ideation, there is a biologically and evolutionary-driven fear of engaging in suicidal behaviors. However, for some individuals with increased capability, this fear is reduced, and they are subsequently more likely to engage in suicidal behaviors. Consequently, our model suggests that there are capability-building risk factors that contribute to the progression from suicidal ideation towards suicidal behaviors, which stem from experiences of child maltreatment.

In the interpersonal theory of suicide, capability includes two components, both of which are not innate but acquired or learned throughout the lifetime: reduced fear of death, and an increase in pain tolerance (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010). In contrast, the three-step theory posits that capability can also be trait-like, or dispositional, in addition to acquired. This theory also considers the role of practical sources of capability, such as access to lethal means (Klonsky & May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). In our model of child maltreatment and youth STBs, we focus specifically on the role of acquired capability. The developmental consequences of child maltreatment are multifaceted, and include several outcomes related to an increased capability for suicide. These outcomes include but are not limited to dysregulated responses to stress, substance use behaviors, and engagement in NSSI. Below, we detail how these three specific risk factors might contribute to the ideation-to-action pathway. Note that these risk factors might work by exacerbating the association between suicidal ideation and behaviors (i.e., acting as a statistical moderator), or by contributing directly to the likelihood of suicidal behaviors (i.e., having a direct statistical association with suicide attempts).

As detailed above, child maltreatment and other adverse, chronic stressful experiences in childhood can predict future dysregulation in physiological stress response systems (Gunnar et al., Reference Gunnar, Morison, Chisholm and Schuder2001; Lovallo, Reference Lovallo2013). Specifically, a blunted physiological response to acute stressors is characteristic for youth and adults who have undergone traumatic childhood experiences like child maltreatment (Lovallo, Reference Lovallo2013). There is some empirical evidence for the role of blunted stress reactivity in the capacity for suicidal and self-harming behaviors. For example, a recent study with adolescent girls found that psychosocial stressors predicted suicidal ideation, while the combination of psychosocial stressors with blunted HPA function predicted suicidal behaviors (Eisenlohr-Moul et al., Reference Eisenlohr-Moul, Miller, Giletta, Hastings, Rudolph, Nock and Prinstein2018). Additionally, in the same study, adolescents with a history of suicidal behavior had a significantly more blunted cortisol response to a psychosocial stressor compared to those with only suicidal ideation and to controls with no lifetime suicidal ideation or behaviors. A separate study also found that adolescent girls with a history of self-harm had a blunted HPA reaction to a laboratory social stress task compared to girls with no history of self-harm (Plener et al., Reference Plener, Zohsel, Hohm, Buchmann, Banaschewski, Zimmermann and Laucht2017).

Similarly, youth who suffer from child abuse and neglect are more likely to engage in substance use behaviors, including alcohol, marijuana, and other drug use (Cicchetti & Handley, Reference Cicchetti and Handley2019). Substance use is a major proximal risk factor for engagement in suicidal behaviors among youth (Esposito-Smythers & Spirito, Reference Esposito-Smythers and Spirito2004). For instance, in a case-control study, substance use disorders were significant risk factors for adolescent suicide attempts (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Cornelius and Lynch2002). Substance use was also associated with suicide attempts, after controlling for sociodemographic factors and psychiatric disorders including suicidal ideation, in a cross-sectional study using a community sample of adolescents (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hoven, Liu, Cohen, Fuller and Shaffer2004). Additionally, a recent study found that cannabis and other illicit drug use predicted the transition from suicidal ideation to attempts in a high-risk sample of adolescents (Mars et al., Reference Mars, Heron, Klonsky, Moran, O’Connor, Tilling, Wilkinson and Gunnell2019).