Stereotypes about prehistoric women have been recognised for many years; this book sets out to illustrate just how wrong and misleading such stereotypes really are. Indeed, it seeks to demonstrate the centrality of ‘Lady sapiens’ in the Palaeolithic. This is an inspirational contribution to the current debate on human evolution and behaviour, offering food for thought that extends beyond gender roles to other aspects of social organisation, such as altruism and cooperation.

The book is the result of a documentary project led by Thomas Cirotteau and Eric Pincas, in which a group of scholars—predominantly based in France—were interviewed about the archaeological and ethnographic evidence concerning women in prehistory. Along with Jennifer Kerner, the authors tell the resulting story of ‘Lady Sapiens’ in seven short and readable chapters aimed at a wide public audience. The authors explain how archaeological data (e.g. human remains) and ethnographic evidence are evaluated and interpreted, helping the non-specialist reader to make sense of the large body of complex information from diverse archaeological sites and differing periods. The text is enriched with interview transcripts, which provide an engaging conversational narrative, with concrete examples and expert opinions; conversely, there are no in-text citations to the scholarly literature.

In the first part of the book, the authors deconstruct, and then reconstruct, the image of ‘Lady Sapiens’. Early anthropological assumptions about the physical appearance of Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers in Europe, some 50 000 years ago, are very different from what we know based on the evidence available today. Ancient DNA and osteoarchaeological research now show, for example, that Palaeolithic populations were generally dark-skinned, blue-eyed and of athletic build. Many physiological changes, such as depigmentation, that led to the features common among modern Europeans did not begin until the Neolithic period.

If the physical appearance of women in the Palaeolithic is not what it was once thought, nor were their social roles. The second section of the book discusses the recurring themes addressed by scholars over the past 50–60 years, in particular: body decoration, sexual life and gender roles. Many researchers, for example, have observed that personal adornments, such as pendants and bracelets, served not only as markers of identity or grave goods for the afterlife, but also as important, embodied symbolic values in the social lives of Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers. These material cultural markers, it is argued, also played essential roles in women's lives with regards to sexuality. The authors observe that populations were well aware of the power of sexual behaviour, both for procreation and in relation to pleasure and social bonding. The recurring depiction of female and male sexual attributes emphasises the importance of sex. The authors point, for example, to the research of Marc Martínez and colleagues, who hypothesise that these objects and representations were used in ceremonial performances (p. 90). Further, it is argued that prehistoric women also had deep understanding about their bodies during pregnancy, lactation and the menopause; they might also have effectively managed birth intervals through prolonged breastfeeding, which significantly inhibits fertility, as argued by Vincent Balter (p. 114). At the same time, many contemporary hunter-gatherers and traditional societies maintain cultural conventions and taboos that shape and significantly limit women's lives. An important example discussed here is the ‘blood taboo’, which prohibits women from participation in life-threatening activities, as they are considered valuable group members to be defended and protected from danger. Nonetheless, as observed at the 8000-year-old site of Wilamaya Patjxa and at other North American sites, where female individuals are buried alongside weapons, women were also engaged—directly or indirectly—in hunting and in the production and management of the tools needed for butchering and killing (pp. 134–36).

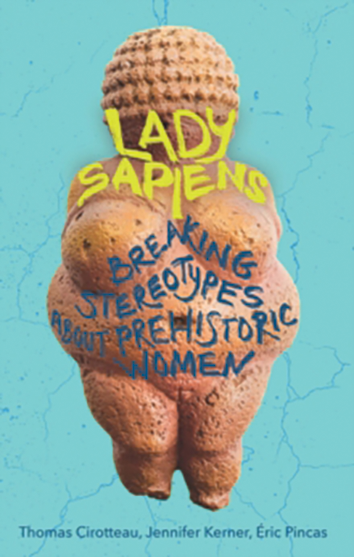

The main message that this book aims to convey, therefore, is that women played essential roles in all aspects of prehistoric life, and were just as powerful, independent and versatile as men, while taking on complementary and interchangeable responsibilities within their communities. Regardless of age or fertility, social roles adopted by women included hunters, stone-tool makers, caregivers and leaders. Moreover, the authors see in these women the ability to perform these varied roles, and their cooperative approach to them, the basis for the survival of our species. It is also argued that prehistoric women possessed a distinct relationship with the natural world, particularly with plants, as hypothesised—perhaps somewhat stretching the interpretation—at sites such as Ohalo II in Israel. The authors therefore see women as highly potent: whether feeding children, healing the sick, practising shamanic or other pseudo-magical rites, climbing the social ladder and even attaining the divine. All of this leads the authors to the question: are the plump female ‘Venus’ figurines representations of divinity, as sometimes argued, or perhaps, instead, acclamations of profane female capabilities?

I highly recommend this book. In particular, I very much welcome the authors’ combining of the results of scientific analyses, such as ancient DNA studies, with insights from the social sciences. One could arguably go even further in breaking gender stereotypes; the danger of counterproductive outcomes is, however, real. We must be careful to avoid the creation of new stereotypes through the use of Eurocentric concepts, outdated terminology such as ‘Venus’ figurines, and the cherry-picking of case studies. In summary, we should be grateful to the authors of this popular science book, and their scientific advisor Sophie de Beaune, for furthering discussion of prehistoric women and their lifeways.