Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) remain a worldwide public health problem that requires regional and global strategies for control and elimination. However, locoregional differences lead to inconsistent progress regarding health indicators associated with STI and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (World Health Organization, 2016; World Health Organization, 2020). Such differences may occur because public health policies are implemented to varying degrees across regions and socioeconomic context varies among local populations, given that STIs disproportionately affect people with low income and education levels and that groups affected by social inequality also have limited knowledge about STIs/HIV (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Wang, Shen, Huang, Yang, Hao, Cox, Wu, Tao, Kang and Jia2015; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Ceccato, Kerr and Guimarães2017; Lyons et al., Reference Lyons, Heywood, Fileborn, Minichiello, Barrett, Brown, Hinchliff, Malta and Crameri2017; von Rosen et al., Reference von Rosen, von Rosen, Müller-Riemenschneider, Damberg and Tinnemann2018; Guimaraes et al., Reference Guimarães, Magno, Ceccato, Gomes, Leal, Knauth, Veras, Dourado, Brito, Kendall and Kerr2019; World Health Organization, 2020).

People living in subnormal agglomerates in urban areas are likely to have exposure to STIs that is above the national average and greater than that of residents of other areas. Similar to Africa (Steenkamp et al., Reference Steenkamp, Venter, Walsh and Dana2014; Kerubo et al., Reference Kerubo, Khamadi, Okoth, Madise, Ezeh, Ziraba and Mwau2015; Weimann and Oni, Reference Weimann and Oni2019), subnormal agglomerates are present in urban areas in Brazil and are characterised by an irregular urban pattern, lack of essential public services, and housing located in areas that are deemed inappropriate for occupation (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2020).

Combined prevention of STIs/HIV, which includes behavioural, biomedical, and structural approaches, must consider context, which shapes a population’s risk and vulnerability to these diseases (World Health Organization, 2016; World Health Organization, 2020). Adequate knowledge about STIs/HIV within the population should also be considered when implementing combined prevention strategies, since it influences behaviour, practices, and attitude (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Arisegi, Awosan and Erhiano2014; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Wang, Shen, Huang, Yang, Hao, Cox, Wu, Tao, Kang and Jia2015; Dadi et al., Reference Dadi, Feyasa and Gebre2020; Logie et al., Reference Logie, Okumu, Mwima, Kyambadde, Hakiza, Kibathi and Kironde2020).

In this context, in which individual and social aspects interact with other factors related to health services access and thus influence knowledge about STIs, the theoretical concept of vulnerability has been adopted. It was initially proposed by Mann et al. (Reference Mann, Tarantola and Netter1992) at the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, when the concept of epidemiological risk factors was transmuted using causal reasoning into the operative concept of a risk group.

The concept of vulnerability implies that people’s chances of exposure to illness depend on individual and collective sets. It is structured in three dimensions: cognitive, behavioural, and physical factors that increase the chances of infection. The focus of the social dimension is on cultural, moral, political, economic, and institutional factors that can determine the means of exposure determined at the previous analytical level. The programmatic dimension examines how policies, programmes, and services interfere in these social and individual situations (Ayres et al., Reference Ayres, Paiva, FrançaGravato, Gravato, Lacerda, Della Negra, Marques, Galano, Lecussan, Segurado and Silva2006; Shaurich and Freitas, Reference Shaurich and Freitas2011).

Although the concept of vulnerability has been investigated in numerous studies (Ayres et al., Reference Ayres, Paiva, FrançaGravato, Gravato, Lacerda, Della Negra, Marques, Galano, Lecussan, Segurado and Silva2006; Fagbamigbe et al., Reference Fagbamigbe, Lawal and Idemudia2017; Mahapatra et al., Reference Mahapatra, Bhattacharya, Atmavilas and Saggurti2018; Queiroz et al., Reference Queiroz, Sousa, Brignol, Araújo and Reis2019), only one study has investigated the association between the three dimensions and level of knowledge about STIs (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Ceccato, Kerr and Guimarães2017). Moreover, no such investigation has been carried out in populations of subnormal agglomerates in urban areas in Brazil, particularly the Brazilian Amazon. Epidemiologically, this region is characterised by a growing incidence of HIV and AIDS-related mortality, despite advances in public policies regarding on HIV and STIs in Brazil (Brazil, 2019).

In Brazil, activities aimed at decreasing and controlling STIs and HIV/AIDS are included as a priority in the Unified Health System (UHF), and Primary Health Care (PHC) is the gateway of choice for accessing these activities. In this regard, the Family Health Strategy (FHS) allows intervention by healthcare workers, in the households of the families involved, the Basic Health Unit (BHU), and several social facilities. To allow interaction between education and health, the School Health Programme allows PHC professionals to work in public schools, guiding teachers, students, and the community (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Esperidião and Medina2017; Melo et al., Reference Melo, Maksud and Agostini2018).

Thus, in the present study, we investigated the factors associated with low knowledge about STIs in a peripheral population in the Brazilian Amazon.

Methods

Study design

This observational, cross-sectional study was carried out in Belém, Pará state, northern Brazil. This state measures 1 059 466 square kilometres and has 1 433 981 inhabitants, of whom 38.47% live in subnormal agglomerates. Belém has the sixth lowest Municipal Human Development Index (MHDI) (0.746) among the state capitals of Brazil, and only 303 600 inhabitants (20.43%) are covered by the FHS (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2020).

The site of the present study was a subnormal agglomerate in the Montese neighbourhood, which is covered by the FHS. Data collection took place from 13 October to 9 December 2019 and included people aged 18 years or over who resided in this agglomerate. Individuals with hearing impairment or any cognitive impairment that compromised adequate collection of information were excluded.

The sample size and power was calculated using Statcalc, Epi Info (Version 7.2.2.16) program, according to the following parameters: population size of 42 535 adults living in the area of Montese neighbourhood, an acceptable margin of error of five percentage points, a confidence interval of 95%, a design effect of 1.0 and an expected prevalence of low knowledge of STI/HIV of 30% based on previous studies showing that 46.2% of adolescents in Berlin had never heard of chlamydia (von Rosen et al., Reference von Rosen, von Rosen, Müller-Riemenschneider, Damberg and Tinnemann2018) and that the proportion of low knowledge was 25.5% among men who have sex with men (MSM) in a province of China (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Wang, Shen, Huang, Yang, Hao, Cox, Wu, Tao, Kang and Jia2015) and 26% among Brazilian MSM (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Ceccato, Kerr and Guimarães2017). Ultimately, 320 participants were required.

The four FHS teams provided the researchers with the registration details of families linked to each of the 28 community health agents (CHAs). The data (address, FHS team, and related CHA) of 2,387 houses were entered in a digital spreadsheet (each house was considered a family). The selection process of the participants was carried out in two stages. Firstly, stratified sampling was initially carried out proportional to a number of houses indexed for each CHA (28 strata) of the four FHS teams in the Montese BHU. In the second stage, simple random probability sampling was carried out using a computer-generated list in the Bioestat 5.3 program to select families within each stratum.

At the time of the visit, only one participant of each house/family was chosen. Specifically, the adult who self-referred as responsible for the family was chosen. In cases of loss and refusal, the house was replaced by the subsequent or previous house that was not contemplated in the random draw. The collection was performed by collectors accompanied by the CHA.

Data source

To assess knowledge about STIs, the self-administered Sexually Transmitted Disease Knowledge Questionnaire (STD-KQ) was used (Teixeira et al., Reference Teixeira, Figueiredo and Mendoza-Sassi2015). It consists of 28 knowledge statements with the following possible responses: ‘true’, ‘false’, or ‘don’t know’. This instrument was cross-culturally adapted and translated into Brazilian Portuguese. To assess factors of vulnerability, a formulary was constructed based on information from previous studies (Ayres et al., Reference Ayres, Paiva, FrançaGravato, Gravato, Lacerda, Della Negra, Marques, Galano, Lecussan, Segurado and Silva2006; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Ceccato, Kerr and Guimarães2017; Queiroz et al., Reference Queiroz, Sousa, Brignol, Araújo and Reis2019). The instrument was sent to the macro-project researchers to check for content clarity and adequacy. After some corrections, the questionnaire was pretested in the context of the present study and its adequacy was established by surveying 15 randomly sampled participants who were not included in the study. After this pre-test, no adjustments in form or content were necessary. No tests were performed to assess the reliability and validity of the questionnaire.

Variables

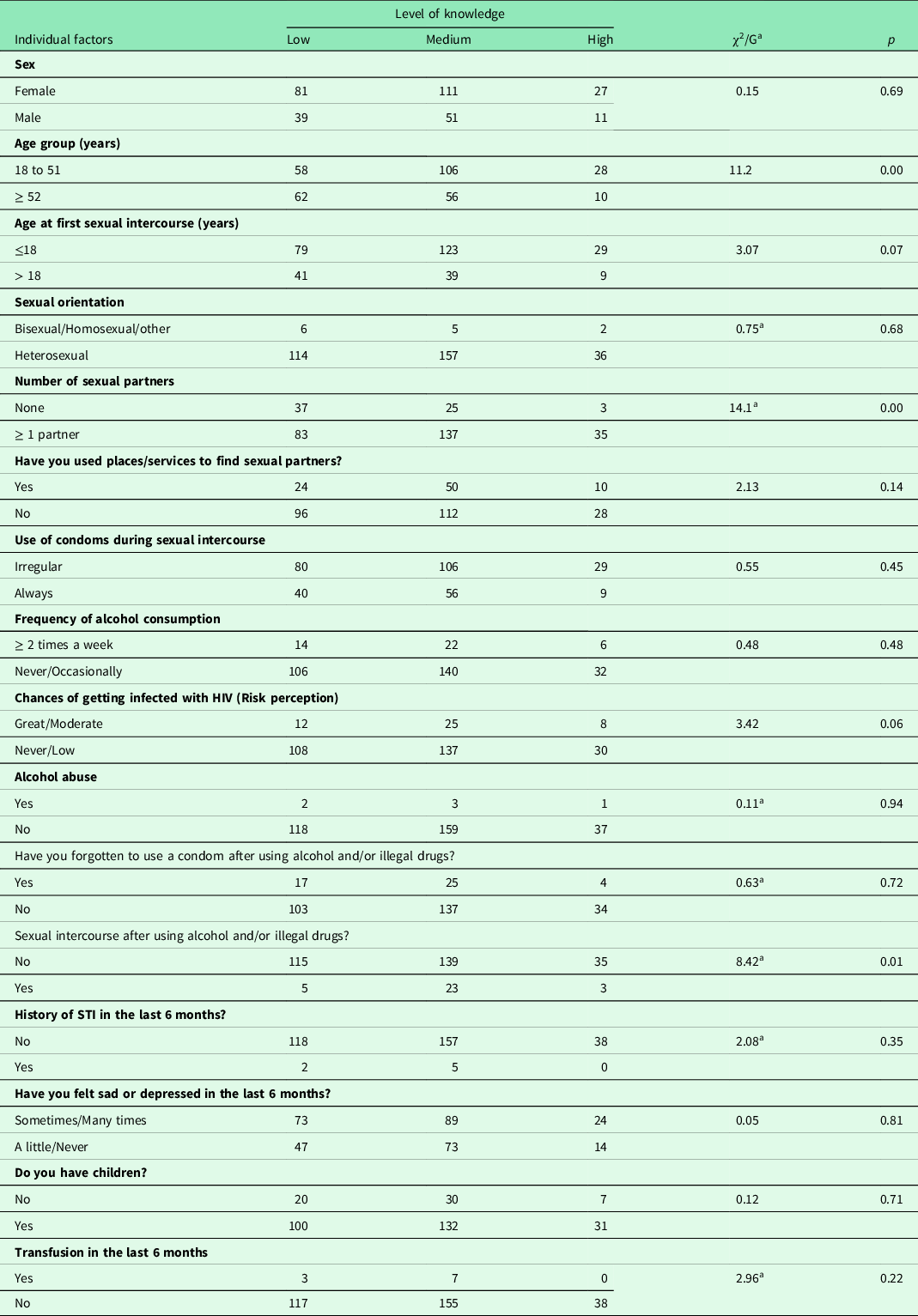

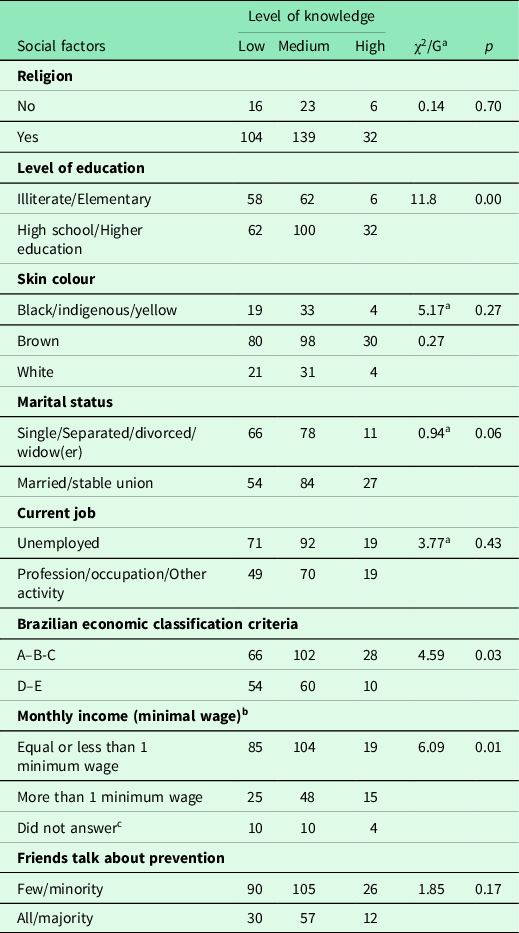

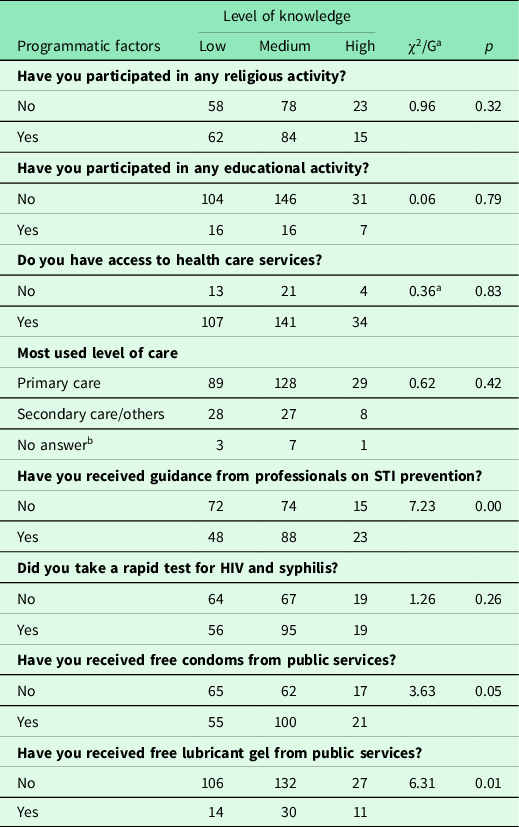

The response variable was the level of knowledge about STI (low, medium, and high), as determined from the data obtained using the STD-KQ questionnaire. Each correct answer was awarded one point, with a total score of 28 if all the answers were correct. Each error or ‘don’t know’ answer had a value of zero. The number of points was (correct answers) calculated, and the participants were grouped into three ordinal categories: Low level (1–13 points); medium level (14–19 points); high level (20–28 points). The independent variables were the dimensions of individual (Table 1), social (Table 2), and programmatic vulnerability (Table 3).

Table 1. Association between the level of knowledge about sexually transmitted infections (STI) and factors of individual vulnerability in individuals living in the subnormal agglomerate of Belém in 2019

a G Test P < 0.05.

Table 2. Association between the level of knowledge about sexually transmitted infections (STI) and factors of social vulnerability in individuals living in the subnormal agglomerate of Belém in 2019

a G test.b Brazilian monthly minimum wage in November 2019 – 998 Real per month.c Not considered for statistical calculation. P < 0.05.

Table 3. Association between the level of knowledge about sexually transmitted infections (STI) and factors of programmatic vulnerability in individuals living in the subnormal agglomerate of Belém in 2019

a G test.b Not considered for statistical calculation. P < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

A database was created using the EPI INFO 7.2.3 program, and descriptive statistics were derived to characterise the study population. For categorical variables, absolute and relative frequencies were calculated. For the continuous variables, measures of central tendency were calculated. The main hypothesis of the study was that the factors of social, individual, and programmatic vulnerability could predict the level of knowledge about STI. This hypothesis was tested using ordinal logistic regression.

Multicollinearity was examined. To analyse differences in the proportions of variables, univariate analysis was performed using the chi-square trend test or G test. All variables with p-values < 0.20 were entered into the intermediate model of the ordinal logistic multiple regression.

A variable coding scheme was determined using the Minitab® software standard. Initially, intermediate multiple ordinal logistic regression models were produced, one for each group of vulnerability dimensions. The final model was produced by inserting all variables that presented p-values < 0.05 in the intermediate models. Variables with higher p-values and no significant association with the response (P < 0.05) were removed one at a time until the final adjustment of the multiple ordinal logistic regression model was achieved.

Quality tests and associated measures were analysed at all stages of regression. To interpret the results, the coefficient value of the predictor was considered in the regression, Z-value, p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, confidence intervals and odds ratios, meeting the criteria of the Minitab® and Bioestat® programs.

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Pará under protocol No. 4 134 220 and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent to participate.

Results

The study sample comprised three-hundred-and-twenty (320) participants with a mean age of 46.09 years (95% CI: 44.39–47.79; standard deviation: 15.46; minimum age: 18 years, maximum age: 87 years). There were 42 participants (13.1%) in the 18 to 27-year age group, 64 (20.0%) in the 28 to 37-year group, 61 (19.1%) in the 38 to 47-year group, 63 (19.7%) in the 48 to 57-year group, 59 (18.4%) in the 58 to 67-year group, and 31 (9.7%) in the >67-year group. Most participants were female (68.4%; 219), and 60.6% (194) had received high school or higher education. Most were married or in a stable union (51.6%; 165), and most were unemployed (56.9%; 182). Regarding level of knowledge about STIs, 120 (37.5%) had low knowledge levels, 162 (50.6%) had medium knowledge levels, and 38 (11.9%) had high knowledge levels.

Table 1 shows the association of knowledge levels with factors of individual vulnerability. Chi-square/G tests demonstrated that the level of knowledge about STIs/HIV was associated with age groups (P = 0.00), number of sexual partners (P = 0.00), and sexual intercourse after using alcohol and/or illegal drugs (P = 0.01). The following variables with p-values < 0.20 were included in the multiple ordinal logistic regression: age at first sexual intercourse (P = 0.07), use of facilities/services to find sexual partners (P = 0.14), and chance of getting infected with HIV (risk perception; P = 0.06).

With regard to social vulnerability (Table 2), univariate analysis revealed that the following variables were significantly associated with level of knowledge about STIs/HIV: with level of knowledge about STIs/HIV: education level (P < 0.00), marital status (P = 0.06), Brazilian economic classification criterion (P = 0.03), and individual income (P = 0.01). These variables were selected for multiple regression, as was the variable ‘friends talk about prevention’ (P = 0.17).

In terms of programmatic vulnerability, we identified a statistically significant association between level of knowledge about STIs and the following variables: receipt of guidance from professionals about STI prevention (P = 0.00) and receipt of free lubricant gel from public services (P = 0.01). The variable ‘receipt of free condoms from public service’ (P = 0.05) was selected for multiple ordinal logistic regression (Table 3).

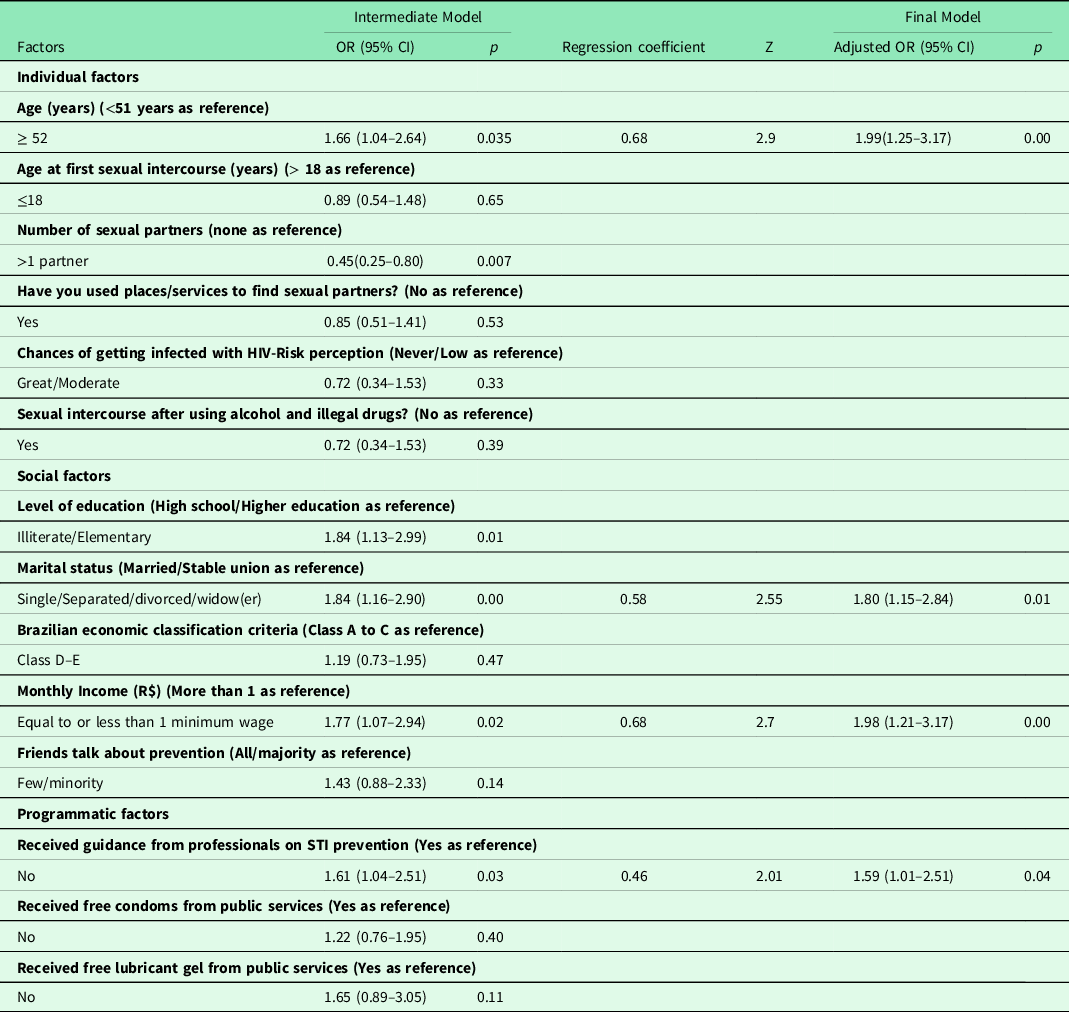

The results of the univariate analysis identified factors that were then introduced into the ordinal regression model. Table 4 presents the regression results. The intermediate model showed the multiple analysis result for factors in each dimension, with factors presenting p-values < 0.05 being included in the final model.

Table 4. Results of the multiple ordinal logistic regression analysis between factors of vulnerability and low knowledge about sexually transmitted infections in adults living in the subnormal agglomerate of Belém in 2019

Ordinal logistic regression (P < 0.05). OR: Odds Ratio.

After adjustment of the model (Table 4), participants aged 52 years or older had a 1.99-fold greater risk (P = 0.00) of low knowledge about STI/HIV; participants with single/separated/divorced/widowed status had a 1.80-fold greater risk of low knowledge (P = 0.01). The risk of low knowledge was 1.98-fold greater among participants with incomes equal to or less than one minimum salary (P = 0.00). The risk for participants who received no professional guidance on STIs/HIV was 1.59-fold higher.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that all dimensions of vulnerability are associated with the level of knowledge about STIs in a population living in subnormal agglomerate in a region in the Brazilian Amazon. In the final model, the number of factors was lower than that in each dimension of the intermediate model. The following factors were independently associated with low knowledge: age equal to or over than 52 years, single/separated/divorced/widowed status, a monthly income equal to or less than one minimum salary, and non-receipt of professional guidance.

A previous study focusing on vulnerability and HIV knowledge reported different results in the final regression model (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Ceccato, Kerr and Guimarães2017). Among young people in Ethiopia, multivariable regression showed an association between lower HIV knowledge and low education, female sex, married status, and lack of access to TV, radio, and information (Dadi et al., Reference Dadi, Feyasa and Gebre2020). Among women who have sex with women in Southern Africa, the final regression model showed that high STI/HIV knowledge was associated with higher education, regular income, and receipt of personalised information on STIs/HIV (Paschen-Wolff et al., Reference Paschen-Wolff, Reddy, Matebeni, Southey-Swartz and Sandfort2020).

The key vulnerable populations from those previous studies had more risk factors than the current study population, perhaps because of specific differences in local access to health services, the level of public policy implementation, and human rights.

In a hyperendemic HIV area, the highest risk was observed in those who had never married and widowers, and the risk increased with age (Tlou, Reference Tlou2019). In Brazil, young adults have a higher HIV detection rate (Brazil, 2019). One previous spatial analysis study conducted in a state of the Amazon region between 2007 and 2018 showed an increasing HIV incidence in older people, with the city of Belém presenting a spatial-temporal risk for HIV/AIDS (Moraes et al., Reference Moraes, Fernandes, Paes, Ferreira, Gonçalves and Botelho2021). The results of the present study, which was conducted at an individual level, may indicate that lower knowledge about STIs/HIV makes older people more susceptible to these infections, increasing the spatial-temporal risk.

Study participants aged over 50 years may not be adequately reached by mass dissemination campaigns or by the health education strategies of their respective FHS teams. It is important to rethink these strategies in this population since they have an active sexual life and are exposed to risks that increase their susceptibility to HIV (Queiroz et al., Reference Queiroz, Sousa, Brignol, Araújo and Reis2019).

Previous studies have shown that single, divorced, or separated people are more susceptible to HIV infection in subnormal settlements. Low income combined with other precarious social and economic indicators makes marriage unfeasible (Kerubo et al., Reference Kerubo, Khamadi, Okoth, Madise, Ezeh, Ziraba and Mwau2015; Shisana et al., Reference Shisana, Risher, Celentano, Zungu, Rehle, Ngcaweni and Evans2016). Thus, marital status alone was not a risk factor for low STI/HIV knowledge or infection; instead, it interacts with other factors (Ibrahim et al., Reference Ibrahim, Arisegi, Awosan and Erhiano2014; Shisana et al., Reference Shisana, Risher, Celentano, Zungu, Rehle, Ngcaweni and Evans2016).

The social context is related to the distribution of the most prevalent bacterial STIs and HIV (Rowley et al., Reference Rowley, Vander Hoorn, Korenromp, Low, Unemo, Abu-Raddad, Chico, Smolak, Newman, Gottlieb, Thwin, Broutet and Taylor2019; World Health Organization, 2020). In populations with precarious social and economic indicators, health policies have not yet resulted in sufficient social response to reduce the incidence of HIV and mortality from AIDS (Probst et al., Reference Probst, Parry and Rehm2016; Rowley et al., Reference Rowley, Vander Hoorn, Korenromp, Low, Unemo, Abu-Raddad, Chico, Smolak, Newman, Gottlieb, Thwin, Broutet and Taylor2019), indicating that the social context of a population contributes to STI vulnerability.

Regarding the programmatic aspects of vulnerability in this study, previous studies have confirmed the relationship between knowledge about HIV and access to health campaigns and services (Paschen-Wolff et al., Reference Paschen-Wolff, Reddy, Matebeni, Southey-Swartz and Sandfort2020; Koschollek et al., Reference Koschollek, Kuehne, Müllerschön, Amoah, Batemona-Abeke, Dela Bursi, Mayamba, Thorlie, Mputu Tshibadi, Wangare Greiner, Bremer and Santos-Hövener2020). In this dimension, health professionals translate public health policies into concrete actions for the population under their responsibility. However, direct or indirect flaws in their professional performance can leave these groups prone to programmatic vulnerability (Shaurich and Freitas, Reference Shaurich and Freitas2011).

The populations of subnormal agglomerates have a greater need for public services, considering the marked social inequalities in these areas (Weimann and Oni, Reference Weimann and Oni2019; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2020). The low availability of services in these areas affects knowledge about STIs and health services (Newton-Levinson et al., Reference Newton-Levinson, Leichliter and Chandra-Mouli2016; Logie et al., Reference Logie, Okumu, Mwima, Kyambadde, Hakiza, Kibathi and Kironde2020). Identifying people without access to the health system is important to increase knowledge about HIV (Koschollek et al., Reference Koschollek, Kuehne, Müllerschön, Amoah, Batemona-Abeke, Dela Bursi, Mayamba, Thorlie, Mputu Tshibadi, Wangare Greiner, Bremer and Santos-Hövener2020). In this context, income transfer programmes can increase access to health services (Shei et al., Reference Shei, Costa, Reis and Ko2014).

The questions in the instrument used to assess knowledge about STIs/HIV may also affect the results (Teixeira et al., Reference Teixeira, Figueiredo and Mendoza-Sassi2015). This is relevant because there are differences in the population’s knowledge about various STIs and are more suitable for HIV, gonorrhoea and syphilis (von Rosen et al., Reference von Rosen, von Rosen, Müller-Riemenschneider, Damberg and Tinnemann2018; Guimarãres et al., Reference Guimarães, Magno, Ceccato, Gomes, Leal, Knauth, Veras, Dourado, Brito, Kendall and Kerr2019; Koschollek et al., Reference Koschollek, Kuehne, Müllerschön, Amoah, Batemona-Abeke, Dela Bursi, Mayamba, Thorlie, Mputu Tshibadi, Wangare Greiner, Bremer and Santos-Hövener2020), whereas it is of limited value for other STIs, such as genital warts, chlamydia, and herpes (von Rosen et al., Reference von Rosen, von Rosen, Müller-Riemenschneider, Damberg and Tinnemann2018; Koschollek et al., Reference Koschollek, Kuehne, Müllerschön, Amoah, Batemona-Abeke, Dela Bursi, Mayamba, Thorlie, Mputu Tshibadi, Wangare Greiner, Bremer and Santos-Hövener2020), as well as knowledge about the most current means of prevention, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (Guimarães et al., Reference Guimarães, Magno, Ceccato, Gomes, Leal, Knauth, Veras, Dourado, Brito, Kendall and Kerr2019).

The structure of the dimensions of vulnerability (Ayres et al., Reference Ayres, Paiva, FrançaGravato, Gravato, Lacerda, Della Negra, Marques, Galano, Lecussan, Segurado and Silva2006) indicates that lack of guidance by healthcare professionals can interfere with the social and individual situation of study participants, leading to less knowledge about STIs/HIV. The present study was limited because it only involved one urban agglomerate with access to PHC in Brazil. Further studies with populations with these characteristics may show whether the association with programmatic aspects is due to the work process of primary care in the city of the study.

Public health implications

For FHS teams, identifying factors related to vulnerability at the local level allows interventions directed towards the needs of these families. Therefore, the biomedical model of health education is refuted, implying that health professionals alone cannot solve all problems. Nonetheless, the data generated provide evidence for healthcare managers seeking solutions to structural issues related to social and economic policies that affect the way of life and behaviour of these groups.

Conclusion

The present results show that this community suffers from suboptimal levels of knowledge about STIs, which are linked to individual, social, and programmatic aspects. More factors related to the social dimensions of vulnerability were associated with lower levels of knowledge about STIs/HIV. Moreover, there was a complex interaction among the factors and that vulnerability was not limited to the individual context.

Living in a territory covered by the FHS does not guarantee adequate knowledge about STIs and HIV. Intersectoral public policies are essential in low-income populations and subnormal settlement residents. Health education and care actions must involve people at higher risk. Characterising risk and vulnerability allows for the appropriate interventions in populations living in urban subnormal settlements, contributing towards the global goal of eliminating these infections by 2030.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the individuals involved in the present study.

Financial support

This study is part of the Project ‘Situational Diagnosis of Sexually Transmitted Infections in the Amazon Context: Geospatial Analysis, Screening and Development of Educational Care Technologies’ and is funded by Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel is a foundation linked to the Ministry of Education of Brazil, number 1699/2018/88881.200527/2018-01. WLSFs work was funded by a Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação (PROPESP/UFPA) grant. ISSOs work was funded by a Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel grant. Funding source(s) had no involvement for the conduct of the research and/or preparation of the article.

Competing interests

None

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation (466/2012 - Brazil) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Pará under protocol No. 4 134 220

Authors contributions

Glenda Roberta Oliveira Naiff Ferreira, Lucia Hisako Takase Gonçalves, Eliã Pinheiro Botelho conceived the idea for the study, conducted the analysis, drafted the manuscript and had full access to the study datasets. Ingrid Saraiva de Oliveira, Wanne Letícia Santos, Freitas, Aline Maria Pereira Cruz contributed interpretation of the findings and critically revised the manuscript. Renata Karina Reis, Ana Luisa Brandão C, Lira. Elucir Gir contributed to the study design, interpretation of the findings and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper. The authorship agreement is to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.