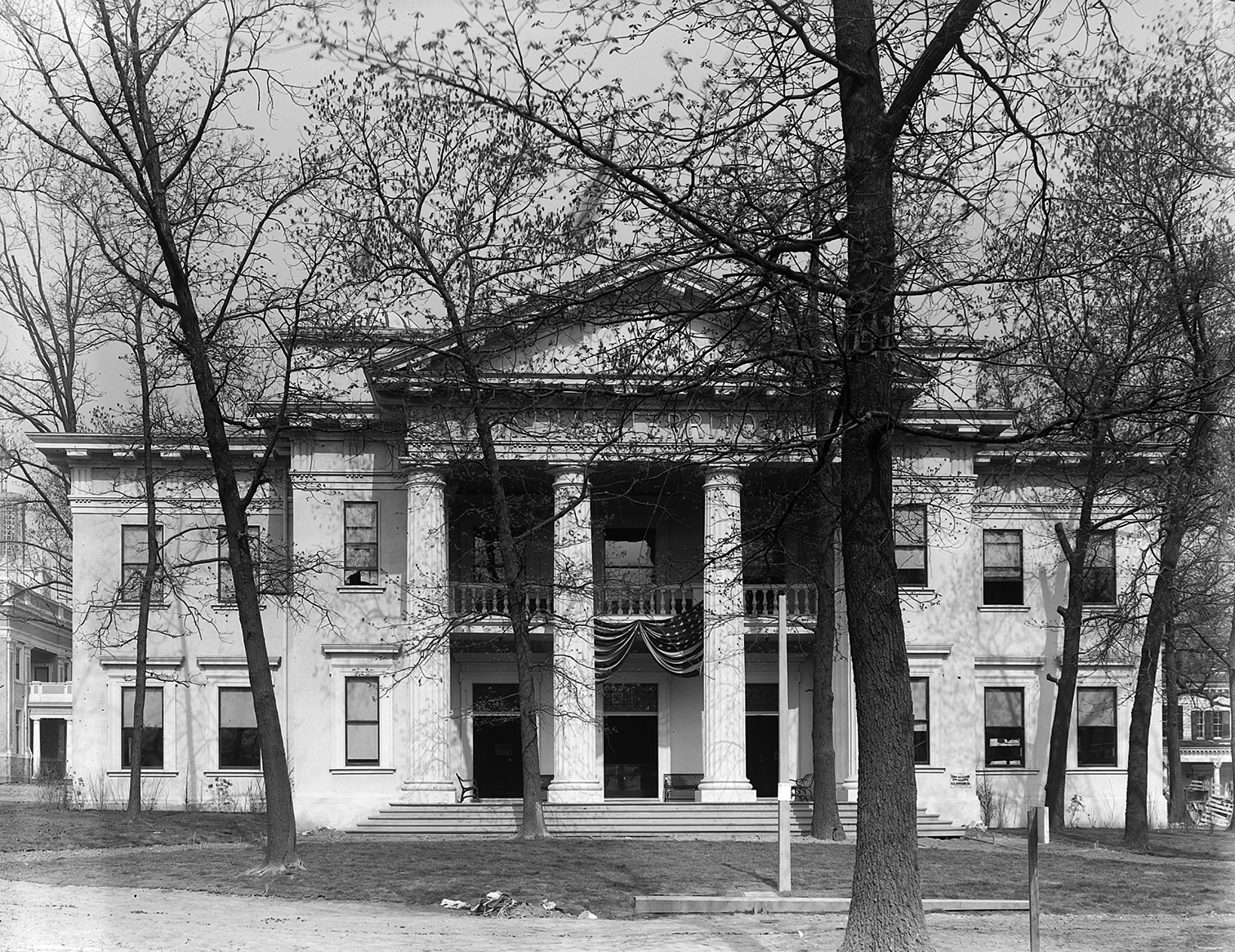

On October 1, 1904, a crowd assembled for Indian Territory Day at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri. World’s fair tradition called for states and territories to host a day of celebration when residents would commemorate their local and national identities with speeches and music. Newspapers estimated 2,000 territory residents participated, including representatives from the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes”—the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole nations. Events were held on the lawn of the Indian Territory building, the territory’s first world’s fair pavilion. Taking up the main floor of this Southern colonial mansion was an exhibit of artifacts, photographs, and artwork representing the territory’s progress. The territory also maintained displays in the Mines and Metallurgy, Agriculture, and Horticulture buildings [Figure 1].

Fig. 1. Exterior of the Indian Territory Building at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Official Photographic Company of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, 1904. http://collections.mohistory.org/resource/728554. Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society.

Indian Territory’s presence at the fair, equal to any state, signaled future statehood. In the day’s first address, David R. Francis, former Missouri governor and president of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, declared, “Every state dates its existence from the time of its inception as an independent part of the country and the efforts of Indian Territory … to assure statehood, deserves the assistance of all parts of the country.”Footnote 1 It remained to be seen, however, if Indian Territory would be entering the Union on its own or jointly with Oklahoma Territory.

This contest over separate statehood, favored by Native nations, versus joint statehood, favored by the territory’s white settlers, led both to seize the public stage of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair as a critical site for negotiating the territory’s future. Indian Territory’s exhibit ultimately did not prevent the dissolution of tribal governments or bring about separate statehood, but Native involvement in crafting the exhibit reveals that Indigenous people used world’s fairs to amplify political messages that subverted the official narrative of progress premised on white supremacy. The Five Tribes challenged the prevailing settler idea that extending U.S. citizenship to Native individuals required destroying their tribal identities. Drawing on the strength of their sovereignty, they demanded full political belonging and rights for Indian Territory within a framework that would preserve a measure of autonomy and a sense of unity for the Five Tribes. By advocating separate statehood, the Five Tribes provided an Indigenous contribution to a broader turn-of-the-century debate over how to integrate a diverse citizenry within the political apparatus of the U.S. nation-state. Reconstruction had magnified the question of how multiracial citizenship and belonging would function in the United States, and by 1904, this question remained unresolved throughout the country, but it was especially pressing in contests over statehood for the diverse territories of the American West.

The politicization of the Indian Territory exhibit reflects how Native nations at the turn of the twentieth century employed cultural production to assert themselves politically. Indigenous histories reveal that political history must expand beyond the study of policy, parties, politicians, and even reform and protest movements. At the end of the nineteenth century, the federal government renounced any pretense of respecting Native sovereignty and quashed traditional options for recourse, including diplomacy and invoking treaty rights. Cultural production, from playing sports to making music and art, became an instrumental alternative tactic.Footnote 2 Native peoples were not only legally blocked from formal political channels but also circumscribed by what Paige Raibmon calls the “binary terms of authenticity.” Defining American Indians and modernity as mutually exclusive, settlers insist that modern American Indians must not be authentic and that “real” American Indians belong to the past. This functions to invalidate Indigenous rights to land and sovereignty. It also restricts Indigenous peoples’ ability to defend those rights because they “find themselves subject to censure when they use nonindigenous forms to address political issues… . The same does not hold true for those who couch their politics in forms that audiences perceive as traditional.”Footnote 3 Cultural spectacles—like exhibits and performances at world’s fairs—that met settler expectations of Indianness had potential to hold more political sway than methods of protest or reform deemed too modern for the “authentic Indian.” The tactical power of participating in the 1904 fair thus went beyond simply raising the visibility of their cause; the Five Tribes operated within a totalizing system of colonialism, but they were able to use existing fissures in the colonial structure to create space for themselves and their ideas. For the Five Tribes, marginalized from political representation, the fair was one place that afforded this kind of agency. The politics of display in the Indian Territory exhibit expanded their agency over the politics of statehood.

Recognizing the Indian Territory exhibit as a tool of the separate statehood movement reveals that the Five Tribes were more creative in their efforts to preserve self-governance than has been acknowledged. They were also fighting for self-governance later than has been recognized. The 1905 Sequoyah Constitutional Convention—the final campaign of the separate statehood movement—has been portrayed as a weak effort by leaders who expected it to fail, having resigned themselves to the fate of dissolution and joint statehood by 1903, when an earlier request for separate statehood was rejected.Footnote 4 Possibly because of its seemingly inevitable defeat, the movement has received limited attention from historians. Given the divisions within Indian Territory over the issue and the strength of party politics, which ultimately defeated the movement, the feasibility of separate statehood was improbable. It deserves examination, though, because the Native people who worked to preserve their sovereignty did not know with certainty what the future would hold and believed in their right to demand an Indigenous state. Separate statehood was a “path not taken” that reveals the contingency of U.S. colonialism and the creativity of Native peoples who worked to reshape and redirect the colonial project.Footnote 5

Statehood loomed as the culmination of U.S. assaults on the rights of the Five Tribes, driven by settler colonialism, a form of colonialism in which settlers seek to claim a region for themselves by physically and rhetorically alienating Indigenous peoples from their land.Footnote 6 In the 1830s, the federal government forcibly removed the Five Tribes from their southeastern homelands to an area west of the Mississippi River, already home to other Native peoples, that came to be known as Indian Territory. By the time of the American Civil War, Indian Territory covered roughly the lands of present-day Oklahoma. After the war, the United States used the Five Tribes’ Confederate alliances as pretext to demand new treaties. The 1866 Reconstruction Treaties abolished slavery in the five nations and (with the exception of the Chickasaw Nation) extended citizenship and voting rights to Indian freedpeople, people of African descent formerly enslaved by citizens of the Five Tribes. The treaties also compelled the Five Tribes to cede large sections of their lands, used partly to resettle other removed nations. Acceding to the pressure of illegal squatters in Indian Territory, the federal government officially opened the western half to a flood of white settlement in 1889 and organized it under a territorial government as Oklahoma Territory in 1890. The eastern section, comprised of the lands of the Five Tribes and the Quapaw Indian Agency, remained the unorganized Indian Territory, without a unified territorial government.Footnote 7

The punitive 1866 Treaties set the tone for Reconstruction-era American Indian policies that dismantled tribal sovereignty to satiate settler land hunger. With the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act, the United States ended formal treaty-making, establishing the end of sovereign-to-sovereign relations.Footnote 8 The 1887 Dawes Act sought to destroy tribal sovereignty, alienate Native individuals from their cultures, and free up “surplus” lands to sell to settlers. The act also provided for granting U.S. citizenship to Native individuals once they owned their own allotments and demonstrated their abilities as landowners. Although the Five Tribes were initially exempt from the Dawes Act, the 1898 Curtis Act extended its provisions to these nations, assigning a March 1906 deadline for the dissolution of their governments and the partition of their land into individual allotments, including for Indian freedpeople. Statehood was the next step in extending the reach of the settler state into the Native nations of Indian Territory. The Five Tribes had opened Indian Territory to non-Native settlement for the sake of postbellum economic recovery, and by the turn of the century, white and Black residents outnumbered Native people six to one.Footnote 9 Non-Natives lived precariously as lessees. Unless made tribal citizens by marriage, they had no voting rights in elections. Statehood would eliminate the barriers that Native sovereignty imposed on the ability of settlers to acquire land.

Citizens of the Five Tribes conceived of separate statehood as a way to defend their power, cultures, and land. While many traditionalist Natives protested the Curtis Act by resisting the enrollment and allotment process, many progressives pursued separate statehood to secure admission to the Union under the most favorable terms.Footnote 10 Unfortunately for the progressives’ goals, the separate statehood movement ended in disappointment. In 1905, Native leaders, joined by some non-Native settlers of the territory, organized the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention and proposed the state of Sequoyah, named for the inventor of the Cherokee alphabet. The Republican-controlled Congress rejected Sequoyah, a would-be Democratic stronghold, and in 1907 admitted Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory together as the state of Oklahoma. Until that final defeat by party politics, separate statehood held promise for the Five Tribes. If they could not preserve sovereignty—the authority of Native nations to govern their own internal affairs and to engage with the U.S. government on a sovereign-to-sovereign basis—separate statehood advocates hoped to maintain some form of self-governance.

Separate statehood advocates recognized the world’s fair, expected to capture international attention, as ideal for publicizing the territory’s right to self-governance. From the proposal of an Indian Territory exhibit in 1901 to the close of the exposition in December 1904, Native citizens—the heads of the five nations, other political and economic elites, and ordinary individuals—served as official members of planning committees, harnessed the power of the press, donated money and items for display, sought employment on the grounds, and made themselves visible to fairgoers. They exerted their influence over the territorial exhibit to communicate that they had adapted well to Euro-American norms, proving their ability to fulfill the responsibilities of statehood. They simultaneously expressed that they maintained enough distinctiveness to deserve remaining independent from Oklahoma’s much larger settler population.

However, the Five Tribes never had full control during the four-year exhibit planning process. White settlers generally preferred joint statehood with Oklahoma, seeing it as the faster route to statehood, and they worked to craft an exhibit that would convince Congress and Oklahomans that Indian Territory would not be a burden.Footnote 11 They also hoped to inspire further white migration, placing even greater pressure on the federal government to limit Native sovereignty and approve statehood. To achieve these goals, they intended to emphasize the territory’s whiteness, suppressing the persistence of Native identities and continued Native ownership of the land. The “politics of display” describes this negotiation for power between the territory’s Native and non-Native residents over the content and meaning of the exhibit. In museum studies, the politics of display refers to the way that power, in this case over constituting knowledge through an exhibition, is distributed among curators, artists, audiences, funders, and even the objects themselves.Footnote 12 Displays are never neutral, and all exhibitions are enmeshed in the power structures of their creators. As the Indian Territory exhibit demonstrates, the politics of display can take on national policy implications.

Although the United States and other empires used world’s fairs to promote scientific racism and justify colonial and imperial expansion, Native people appropriated these events to defend land and sovereignty. Earlier scholarship denied or minimized the ability of Indigenous participants to exercise agency.Footnote 13 By asserting that Native citizens actively shaped the Indian Territory exhibit, this research draws on newer work that recovers specific modes of resistance at fairs. Historians often emphasize that the very act of performing Indigenous identities at world’s fairs was a form of resistance, given the project of assimilation they faced.Footnote 14 They also focus on the financial opportunities that fairs represented for Indigenous participants, recognizing agency in their negotiations for better pay and working conditions.Footnote 15 However, most of this scholarship has not begun to examine how Indigenous people used their participation to further explicitly political goals beyond the fairgrounds.Footnote 16 The Five Tribes are not the only Native nations who seized the global stage of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair to assert and protect sovereignty and land rights, but they exerted the most direct control over their self-representation on the fairgrounds and in newspapers, leaving behind critical insights into their political imagination. Through efforts at the fair and beyond, separate statehood advocates articulated an Indigenous conception of citizenship, developing a creative vision for a future in which self-determination and U.S. citizenship could converge in a Native state.

Early Plans for a Native Exhibit

At the first suggestion of an exhibit, Indian Territory’s Native leaders quickly took the lead. In August 1901, delegates from across Indian Territory assembled in Okmulgee, capital of the Creek Nation. George McLagan, president of the Okmulgee Commercial Club, had planned the convention “for the purpose of securing concerted action for an Indian territory exhibit” at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, then being organized for 1903 (later postponed to 1904 to allow for more preparation time).Footnote 17 Pleasant Porter, principal chief of the Creek Nation, was elected chairman of the temporary executive committee in recognition of “his hearty and unqualified support” of the exhibit.Footnote 18 Porter, the son of a Creek woman and a white man, was a wealthy merchant and rancher elected principal chief in 1899 on a progressive platform supporting allotment negotiations with the Dawes Commission. Porter sought agreements that would be as favorable to Creek citizens as possible but decried the Curtis Act as unjust legislation.Footnote 19 Porter’s commitment to Native self-rule would eventually lead to his selection as president of the 1905 Sequoyah Constitutional Convention. Also elected to the temporary executive committee were three representatives from each of the five nations, including Douglas H. Johnston, Chickasaw governor; John Brown, Seminole principal chief; Gilbert Dukes, Choctaw principal chief; and Thomas Buffington, Cherokee principal chief.Footnote 20 With the exceptions of Calvin Grant and J. S. Stapler, citizens by birth of the Chickasaw and Cherokee nations, respectively, the remaining nine members were white settlers of the territory, some of whom were citizens by marriage.Footnote 21

In an open letter to the people of Indian Territory, Porter asserted the committee’s intent to use the exposition as an opportunity to challenge stereotypes. He hoped to defy the expectations of those who viewed the territory as backward, explaining that “we propose to place such an exhibit as will astonish the civilized world.”Footnote 22 The Five Tribes had proposed an exhibit for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, but it never materialized; the commissioner of Indian Affairs refused to assist, and the State Department, citing Indian Territory’s status as an unorganized territory with no central governor, denied legal authorization for the territory to arrange and finance the exhibit on their own. This earlier exclusion highlighted the limits of tribal sovereignty under the territory’s existing political configuration.Footnote 23 Now, with Porter’s intentions set on proving the Five Tribes’ preparedness for self-governance, the upcoming fair represented an ideal moment to demonstrate the territory’s progress and transform public opinion. Porter asserted, “There is not a State or Territory in the Union better equipped … to produce and display those things which go to make our country great, than our own beautiful Indian Territory.”Footnote 24 His message of national belonging for Indian Territory articulated the goal of statehood underlying his efforts to organize a successful exhibit.Footnote 25

Porter’s fellow committee member and supporter of separate statehood, Cherokee Chief Thomas Buffington, further detailed plans for an exhibit that would promote readiness for statehood.Footnote 26 In October 1901, Buffington and two other committee members met with fair officials in St. Louis. Interviewed by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Buffington denounced the domination the federal government exerted over Indian Territory’s affairs due to its territorial status, explaining that “we must humbly knock at the back door of congress for what we should be able to seek through the front doors, as our peers are enabled to do… . We wish to make known to the world the fact that we are strong and well equipped and well able to take our place in the sisterhood of states.” Buffington also elaborated on the planned exhibit, stating, “[W]e hope to make an exhaustive display of the ancient life of the territory; the aboriginal arts and customs, the primitive ways of the red man—all that pertains to his earlier state. The most attractive feature of our exhibits, however, should be a comparative display, showing the evolution of the Indian.” Buffington proudly added, “In this way we hope to have an exhibit that would be absolutely unique.”Footnote 27 Only by demonstrating that the Five Tribes had advanced enough to handle statehood but still retained unique qualities and experiences would it be possible to convince white Americans that Indian Territory deserved separate statehood.

Buffington and Porter spoke with knowledge of past expositions, describing an exhibit that would feed into yet subtly challenge the fair’s narrative of white dominance. Louisiana Purchase Exposition organizers tried to build on past fairs, especially the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which had presented a trajectory from savagery to civilization with exhibits of humans and cultures from around the world. In pre-fair publicity and ultimately on the fairgrounds, exposition planners treated the commemoration of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase as an opportunity to solidify the imperial status of the United States and legitimize the recent colonization of the Philippines. Displaying Indigenous peoples from newly acquired territories alongside Indigenous peoples from the American West drew an explicit connection between westward colonial expansion and global imperialism. According to Social Darwinist logic, both actions were justifiable because the subjugated races were not as culturally, intellectually, or politically evolved as white Americans or Europeans.Footnote 28 Buffington and Porter were fully aware that world’s fairs reified racial hierarchy and endowed colonial agendas with scientific authority, yet they remained eager for Indian Territory to participate. They even made clear their intent to emphasize their citizens’ success in adapting to white society. Buffington went as far as adopting the rhetoric of scientific racism, calling American Indians of the past “primitive” and referring to Native progress as “evolution.”Footnote 29 Conforming to the established epistemological framework of international expositions was the best rhetorical strategy available to make their case for self-governance legible and palatable to a settler audience. In addition to seeking popular support, they anticipated that President Theodore Roosevelt and members of Congress, with whom the decision on statehood ultimately lay, would be among the fairgoers.

However, the chief executives of Indian Territory did not retain primary control over the territorial exhibit. It speaks to the political significance of the planned exhibit that Porter, Buffington, and the others took time away from their efforts to preserve sovereignty and maintain unity within their respective nations during the upheaval of 1901 and 1902. Allotment, enrollment, and attacks on tribal governments required time-consuming negotiations with the federal government and resulted in frequent trips to Washington.Footnote 30 Executives of the five nations were also managing internal disagreements between progressives and traditionalists within their own nations.Footnote 31 Perhaps because of their busy schedules, they chose not to remain on the executive committee. After a series of unexplained resignations and replacements between October 1901 and February 1902, only two of the sixteen committee members were citizens of Native nations by birth: Chief Buffington and Joe LaHay, treasurer of the Cherokee Nation.Footnote 32 The planning process also became less urgent; in January 1902, rumors circulated that the exposition would be postponed until 1904, a decision confirmed that summer.Footnote 33 Although the leaders of the Five Tribes were committed to making an exhibit to promote self-governance, circumstances forced them to shift priorities. Their resignations left it entrusted to non-Natives, jeopardizing their plans. It is unclear why the makeup of the committee changed so drastically. The remaining members, predominantly settlers, likely favored selecting replacements who shared similar visions for the territory and the exhibit. They gradually edged out Native authority over the territory’s representation at the fair and the territory’s political future.

“A White Man’s, Not an Indian, Exhibit”

Control over exhibit planning changed hands several times over the next year, but without a budget, little was accomplished. In February 1902, the executive committee had prepared an exhibit appropriation bill for a member of the House Committee on Indian Affairs to introduce to Congress.Footnote 34 The bill was never introduced, possibly because the $100,000 request was seen as too high. A year later, J. W. Zevely, acting U.S. Indian inspector for Indian Territory proposed a much smaller appropriation of $25,000, equivalent to nearly a million dollars today, to be matched by the people of the territory by June. According to Zevely, the impetus came from the people of the territory. Congress approved the appropriation and a separate $50,000 appropriation for the District of Alaska’s exhibit.Footnote 35

More non-Natives took an interest and began making plans for an exhibit that would help achieve a whiter Indian Territory. In March, four non-Native mayors invited other mayors and the heads of Native nations to South McAlester to discuss raising $25,000. Of the four, only one had served on the earlier committee. In their letter to territorial leaders, they asserted, “The people of the world are unmindful of the progress that has been made toward civilization, and … we feel that such an exhibition of progress can be shown at the World’s Fair as will greatly augment the inflow of capital and population to the Territory.”Footnote 36 Their ambition to inspire further white migration to the territory separated them from the earlier Native planners; after all, the influx of white settlers had placed pressure on the federal government to intervene through the Curtis Act. Although both groups hoped to show off their territory’s development, their motives diverged.

Despite this tension, Natives and non-Natives attended the meeting in South McAlester. However, settlers maintained control over the planning process. J. J. McAlester, H. B. Johnson, J. E. Campbell, H. B. Spaulding, A. J. Brown, and W. L. McWilliams were selected for the advisory board. Brown was a citizen of the Seminole Nation by birth (and the nation’s treasurer), Johnson was a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation by birth, and the others were white settlers. McAlester was a dual citizen of the Chickasaw and Choctaw nations by marriage, Spaulding was a Creek citizen by marriage, and Campbell was married to a Lenape (Delaware Tribe of Indians, or Cherokee Delaware) woman but not officially a citizen.Footnote 37 Although granted certain citizenship rights, intermarried whites did not necessarily serve the best interests of Native nations. They nevertheless remained an important link to the planning process for the Five Tribes. Frank C. Hubbard, a noncitizen white, was appointed as world’s fair commissioner. Because Indian Territory had no means of collecting taxes, the board had to rely on voluntary contributions.Footnote 38 They employed letter writing campaigns and newspaper publicity to motivate political and business leaders to take charge of local fundraising efforts, setting quotas for each town’s contribution. Natives and non-Natives alike demonstrated their commitment to the territory’s representation at the upcoming fair by successfully raising the $25,000 by the deadline.Footnote 39

With funds available and work on the fairgrounds underway, Indian Territory could finally set to work making their exhibit a reality. After the money was paid into the U.S. Treasury, Secretary of the Interior Ethan Hitchcock took nominal charge of the exhibit.Footnote 40 Without a centralized territorial government, Indian Territory was not empowered to lead its own commission or designate members. The federal government also did not recognize any right of the Five Tribes to determine their own representation. Hitchcock appointed Assistant Secretary Thomas Ryan chairman of the Indian Territory Exhibit Commission. Ryan appointed the same six men on the existing advisory board and retained Hubbard as executive commissioner. By August, a representative of the Coal Operators’ Association, William Busby, another noncitizen white, was added.Footnote 41 Hubbard, the only paid commission member, was responsible for day-to-day management of the planning process and had the most direct influence over the exhibit. With minimal administrative capacity on the ground, the federal government leveraged Hubbard to extend its authority over a territory not yet incorporated into the federation of states. Through Hubbard, deputized as an agent of the state, the federal government attempted to secure its vision for a continental empire settled by a white majority.Footnote 42

More than anyone else involved, Hubbard emphasized the whiteness of the planned exhibit and the territory. In April 1903, an Oklahoma newspaper quoted him saying, “We will make no moccasin exhibit… . Some people, especially in the east, think that we are all Indians out here, blanket Indians at that, running wild and taking scalps whenever a white man shows up.”Footnote 43 He made his point more bluntly a few months later in an interview with a St. Louis newspaper. Hubbard asserted, “The scalping knife, the tomahawk and the tepee will have no place in the exhibit of the Indian Territory… . It will be a white man’s, not an Indian, exhibit.”Footnote 44 Hubbard’s curatorial vision of Native erasure clashed with the plans put forward by Porter and Buffington less than two years earlier. They had not imagined a sensationalist and stereotype-reinforcing exhibit either, but Native people were central to their narrative of the territory’s development. Hubbard, however, conveyed his belief that Nativeness in any form was too closely aligned with savagery in the American imagination and risked contradicting the message that Indian Territory was ready for statehood with Oklahoma.

Hubbard also took steps to ensure that fairgoers would perceive the shared future of the territories. In July 1903, Hubbard received a letter from C. A. McNabb, a farmer and merchant in charge of Oklahoma’s agricultural and horticultural displays, who later served as secretary of the territory’s Board of Agriculture. McNabb sought Hubbard’s cooperation in placing the territories’ booths side by side in the agriculture and horticulture buildings “with the idea that they will ultimately become one grand State whose products can not be equalled by any other State in the Union.”Footnote 45 Hubbard acted on McNabb’s suggestion, selecting booths adjoining Oklahoma in the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy and the Palace of Horticulture.Footnote 46 In June 1904, the Oklahoma Commission forwarded Hubbard an invitation from T. B. Ferguson, governor of Oklahoma Territory, to participate in Oklahoma Day. Ferguson wrote, “I trust that we will have the hearty co-operation of the Indian Territory and that their representatives will be made to feel that it is their day as much as ours, as we are soon to be joined with them in statehood.”Footnote 47 Hubbard clearly agreed with this sentiment because he later invited Governor Ferguson to give the closing address on Indian Territory Day.Footnote 48 In the display halls and on the territory days, Hubbard presented joint statehood as destiny, fulfilling the desires of non-Native settlers.

Yet Native citizens continued to exert influence over the exhibit and were unwilling to let Hubbard whitewash Indian Territory for the sake of joint statehood. Between summer 1903 and early 1904, Hubbard changed his mind on making a “white man’s, not an Indian, exhibit.” In January 1904, he made an unsuccessful request for more money from the Department of the Interior to install “genuine Indian hand work, pottery, bead work, etc., etc., illustrating the progress of the real Indian during the past two or three generations—from the time when they were primative [sic] up to the present—when they are the social and educational equal of the citizens of other states and territories.”Footnote 49 He also sought and received approval to place transparencies “symbolical of the Five Civilized Tribes” in the building’s windows.Footnote 50 The timing indicates that the commissioners convinced Hubbard of the necessity of highlighting Native identity. His requests came within two weeks of the first commissioner meeting in St. Louis, which provided all of them an opportunity to tour the building and “confer on the grounds relative to the exhibits.”Footnote 51 Finding a generic colonial-style mansion, they likely made it clear to Hubbard that the space needed to better represent the Five Tribes. After this meeting, Hubbard stopped pursuing his original vision of Native erasure. His request for additional funds denied, Hubbard used existing funds to secure an impressive collection of donated Indian objects.

Communication with Native citizens also appears to have inspired Hubbard’s decision to hire living representatives of the Five Tribes to greet visitors. In April 1904, Hubbard wrote to the Interior Department of his plan for a paid “Indian boy clerk” position in the territorial building to be filled on a monthly rotating basis by a young man from each of the Five Tribes. This would set Indian Territory apart from other state and territorial buildings, which each engaged an individual female hostess. According to Hubbard, it would “give some few deserving Indian youth the opportunity of seeing the World’s Fair” and give visitors the chance to observe a “sound, healthy, intelligent and competent” Indian boy, a “representative type of his nation.”Footnote 52 In the preceding months, Hubbard had received no fewer than a dozen letters from or about young Native men seeking employment at the fair. These letters proudly emphasized their Indian heritage. Several letters made clear the applicant’s desire to learn from the fair, exactly what Hubbard later described as the position’s purpose. Former exhibit committee chairman Joe LaHay, Cherokee, wrote Hubbard, “I have a son 17 years old who is crazy to get a position in the Territory building… . It would be a great education for him.”Footnote 53 Joshua Anderson, a young Choctaw, explained in his letter, “I was at St. Louis last summer and saw the different buildings which I fancied very much. Would like to work thee [sic].”Footnote 54 Ultimately, Hubbard selected four clerks: Martin Tehee, Cherokee; John H. Crutchfield, Cherokee; Oray McNaughton, Quapaw Agency; and A. L. McIntosh, Choctaw.Footnote 55 The initiative of Native citizens provided Hubbard with a unique way of promoting Native identity, in stark contrast to his earlier plans.

Subverting Settler Expectations

The Five Tribes had less control over the Indian Territory exhibit by 1903 than they had in 1901, when their executive leaders were in charge, but Native citizens continued to shape the exhibit in powerful ways. Having their own citizens on the commission provided an official means of influencing the planning process. It also took on direct political meaning in the pursuit of separate statehood. In November 1902, representatives from the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek nations, including Pleasant Porter, adopted resolutions calling for separate statehood for Indian Territory upon the dissolution of the Five Tribes’ governments in 1906 and sent them to the Senate to be read in opposition to joint statehood. As they asserted, “It is incumbent upon us as a self-governing people to propose a State form of government for the country owned by us.”Footnote 56 In September 1903, they met again and a few months later sent a joint petition for separate statehood to Congress, in the form of resolutions adopted by each nation. The Creek and Choctaw resolutions shared language delineating the reasons for separate statehood. Most importantly, the citizens of the five nations “would have more influence in the organization of a State formed out of Indian Territory than they would have if a State were formed by the union of Indian Territory and Oklahoma.”Footnote 57

The resolutions made several claims about Indian Territory’s fitness for statehood, from its size and population to its agricultural productivity, and the closing argument concerned the territorial exhibit:

Citizens of the Five Civilized Tribes have been prominent in the upbuilding of the Indian Territory and are to-day foremost in all enterprises for its permanent development. Proof of this is that of the board of seven commissioners selected to cooperate with the Interior Department in the management of the Indian Territory exhibit at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, five are citizens of the Five Civilized Tribes. The citizens of the Five Tribes are qualified to organize a State government …Footnote 58

Given that only two commissioners were citizens by birth, the petition claimed intermarried whites as full citizens. These commissioners were not even necessarily in favor of separate statehood. H. B. Johnson had served as temporary secretary of a joint statehood convention formed in January 1903.Footnote 59 Nevertheless, the Five Tribes hoped that mentioning their citizens’ service on the commission would testify to their public spirit—their commitment to the entire territory and to the United States. The petition did not result in separate statehood, but for the time being, Oklahoma was also not admitted as a state. Throughout 1903 and into 1904, with separate statehood unassured yet potentially still within reach, proving capacity for self-governance at the world’s fair remained a priority for the Five Tribes.

Although no longer an official commission member, Pleasant Porter continued using the fair as a site for promoting the Five Tribes’ progress. In April 1903, Porter, along with Green McCurtain, Choctaw principal chief and fellow separate statehood advocate, attended the exposition’s dedication ceremonies.Footnote 60 As part of the celebration, Porter served as a parade marshal.Footnote 61 Porter also maintained direct involvement in planning the Indian Territory exhibit. In September 1903, just before construction on the exhibit building began, Porter joined commissioners Hubbard, McWilliams, and Spaulding on a visit to St. Louis to see the grounds and meet with world’s fair officials.Footnote 62 Principal Chief Porter’s continued participation demonstrated the enduring political significance of the exhibit to the Five Tribes.

Ordinary Native citizens of Indian Territory found their own ways to contribute to the exhibit and present their history and identity to fairgoers. Natives and non-Natives from across the territory sent coal, fruits, vegetable, grains, and other samples for Indian Territory’s booths in the various exposition palaces. They also sent pottery, beadwork, tobacco pouches, stone clubs, tomahawks, and other objects of historical value for the territorial building.Footnote 63 Native women sent their needlework and oil paintings, which were used to convey the modern advancements made by the Five Tribes.Footnote 64 Narcissa Owen, a Cherokee citizen by birth, painted and donated portraits of Sequoyah, Thomas Jefferson, and Jefferson’s descendants.Footnote 65 Her painting of Sequoyah was later displayed at the 1905 Sequoyah Constitutional Convention, where Owen’s son, Robert Owen, Jr., an early proponent of separate statehood and future U.S. Senator from Oklahoma, played a leading role.Footnote 66 At the time, Owen explained that she donated the portraits to the exhibit out of “a desire to do my part as a patriotic woman of the Cherokee Nation and a lover of old Virginia.”Footnote 67 In her memoirs, she further claimed to have done so “to do my part in honoring [Jefferson]” for purchasing the Louisiana Territory “and at the same time show the world that the Cherokees were a cultured and civilized people.”Footnote 68 Native donors believed they were not only fulfilling a duty to their nations and territory but also staking their claim on American history and asserting a role for Indians within the United States.

Because Native citizens never gave up on expressing sovereignty through their exhibit, Commissioner Hubbard’s plans for “a white man’s, not an Indian, exhibit” did not prevail. On April 30, 1904, the exposition and the Indian Territory building opened to the public.Footnote 69 As visitors entered the main hall, they encountered four large cases filled with historic artifacts from Native peoples in and beyond Indian Territory. Even though Hubbard had specifically stated that tomahawks would “have no place” in the exhibit, a tomahawk collection was one of its most celebrated features. Other objects included bows and arrows, pottery, beadwork, and tobacco pouches.Footnote 70 Past the entrance hall were two more exhibit rooms. The art and educational exhibit contained paintings, needlework, beadwork, and other handcrafted items produced by the territory’s students and other residents. The photographic room displayed 500 photographs commissioned for the exhibit, “taken from all parts of Indian Territory and representing the actual status and present commercial conditions of the Indian Territory.”Footnote 71 These photographs captured the territory’s fine houses, banks, businesses, coal mines, oil fields, and prominent citizens, demonstrating the territory’s economic and social advancement. They also captured the schools, orphanages, and other social institutions run by the Five Tribes, which proved their ability to provide for their own citizens.Footnote 72 With a floor plan steering visitors from Native past to Native present, the exhibit presented a trajectory of progress premised on Indian ingenuity.

From opinions recorded in national print media and visitor logs, the completed exhibit was more a fulfilment of what Native political leaders had originally imagined in 1901 than an expression of Native erasure and white control over Indian Territory. Visitors were impressed and came away understanding that Indian Territory had advanced through Native effort, not in spite of Native presence in the territory. In six volumes of exhibit visitor logs, hundreds of fairgoers from around the country left favorable comments, many claiming that it was the “Best I have seen” or “Best of kind.”Footnote 73 Visitors also absorbed the intended message of progress. As one promotional booklet put it, “Purposely all things here show progress and development.”Footnote 74 In the visitor logs, one person noted, “The Indian is progressing.”Footnote 75 Another wrote, “Your exhibit shows bright, intelligent people.”Footnote 76 An Ohio woman went so far as to write, “I think some white folks had better hurry and ketch [sic] up. The Indian is par excellence in work.”Footnote 77 Visitors left believing that even if the Five Tribes might have lived an “uncivilized” existence in the past, they were now educated, modern Americans with towns, buildings, and institutions worthy of admiration.

Indian Territory’s participation in the world’s fair also succeeded in convincing visitors of the territory’s readiness for statehood. One headline announced, “Remarkable Recent Development and Wonderful Resources of the Future Great State Are Admirably Set Forth.” Footnote 78 After viewing the exhibit, some visitors even jotted down support for statehood in the registers of visitors. “Should be admitted,” wrote one Texan.Footnote 79 A man from Michigan asserted, “Should be a state,” and someone from Mississippi commented, “Give Indian Teritory [sic] statehood”Footnote 80 Others implied support with less direct remarks like, “The Territory is ahead of many states,” “You’ll get there,” and “Will have its day.”Footnote 81 The exhibit’s narrative of Native progress was effective in demonstrating preparedness for statehood.

Yet the Native citizens of Indian Territory might not have seen this as a total success. The statehood that the public imagined for Indian Territory was not necessarily an independent one. Although most visitors who penned their support for statehood did not indicate what kind they supported, a few visitors, mainly from Oklahoma Territory, clearly endorsed joint statehood. “We are one,” “a crowning addition to our own state,” and “we will be one,” commented three Oklahomans.Footnote 82 This was to the satisfaction of non-Natives, but for Native citizens the exhibit might not have fully lived up to their aspirations.

Although many fairgoers received the message of progress, they did not always shed their stereotypical views of American Indians nor recognize that Native nations could govern themselves. Several jokesters left patronizing comments, including “Heap Big Ingin” and “Big Injuns still here.”Footnote 83 A promotional booklet provided more nuanced commentary reflecting disbelief in Native self-governance. After first describing “a collection of crude implements and trophies of chase and war in the main entrance hall,” the author wrote, “As if to impress the progress made by the red men, in the photograph room are scenes in which fine buildings of the towns and comfortable homes of the educated wards of the government are shown.” He viewed even the wealthiest and most powerful Native people as under white dominion. Describing the second floor, which contained no exhibits, only Hubbard’s office, resting rooms, a ladies’ parlor, and a reception hall, the author claimed it “may well be said to belong to the increasing, progressing white man who impatiently waits for admission to the sisterhood of States.”Footnote 84 Having outlined a progression from warlike Indians of the past to well-mannered Indians of the present, the writer indicated that the final progression would be from a Native territory to a white state. Through the Indian Territory exhibit, Native citizens had succeeded in “astonish[ing] the civilized world” with their progress and even in demonstrating their fitness for statehood, but they could not fully overcome their visitors’ racist beliefs.

This cannot be attributed solely to any shortcomings of the exhibit itself. The potency of colonial narratives means that even a well-crafted counternarrative can strengthen settlers’ preconceived notions rather than convince them to rethink their views. Paige Raibmon terms this the “Catch-22 of colonialism,” explaining that “engagement with colonial agents and categories—whether acquiescent, collaborative, or defiant—further entrenched colonial hegemony.”Footnote 85 Considering the intensity of the racist, colonial, and imperialist narrative of progress on which the entire Louisiana Purchase Exposition centered, it is not surprising that an individual exhibit was unable to fully communicate the notion of Native sovereignty.

However, failing to fully undermine settler assumptions did not diminish the power Native people exercised in controlling their own narratives and creating their own meanings from their participation.Footnote 86 This power shows through in visitor log comments by Native visitors. The Indian Territory exhibit served as a place on the fairgrounds where they could affirm their Indigenous identities. Edna Labadie from Kansas wrote, “I am a little peoria Indian girl.”Footnote 87 An unnamed visitor drew a side profile of an Indian man wearing a feather headdress. He labeled it, “Drawn by a half breed Choctaw boy.”Footnote 88 Lizzie Antone, Creek Nation, signed “Halfbreed Indian” next to her name, and Mrs. F. S. Miller, Cherokee Nation, wrote “Cherokee Indian” next to hers.Footnote 89 Martin Tehee of the Cherokee Nation, who served the June rotation as the “Indian boy clerk” greeting visitors in the territorial building, stayed on at the fair by getting hired as a member of the Jefferson guard, the fair’s security force.Footnote 90 Tehee returned to the territorial building multiple times, marking his presence by signing the visitor logs.Footnote 91 Native people from Indian Territory and beyond took pride in the exhibit. Despite everything that conspired to erase, silence, or contradict them—the federal government, white settlers like Executive Commissioner Hubbard, and the fair’s narrative of Indigenous inferiority—the exhibit’s Native planners and supporters managed to communicate that Indian Territory was worthy of respect and that Native nations were integral in the development of the territory. In that sense, the exhibit served their political goals.

From Indian Territory Day to the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention

On Indian Territory Day, after Exposition President David R. Francis praised the territory’s efforts to achieve statehood, Pleasant Porter spoke before the crowd gathered on the lawn of the territorial building. T. B. Ferguson, Oklahoma governor, gave the closing remarks, having been extended this honor by Hubbard. Together, Porter, vocal proponent of separate statehood, and Ferguson, by this time an advocate of joint statehood, personified Indian Territory’s two possible futures. They also embodied the contest between settlers and Native citizens—and between Hubbard and Porter in particular—over the content and meaning of the territory’s representation at the fair. The main message of Porter’s speech was that the Five Tribes had reached their advanced level of development by adopting the habits and tools of white society.Footnote 92 Although Chief Porter spoke favorably of assimilation, he also wore full regalia that day, complete with a Plains Indian feather bonnet.Footnote 93 Porter simultaneously emphasized his and his territory’s ability to fit in with the rest of the country and attracted attention to their distinctiveness as Native people [Figure 2].

Fig. 2. Pleasant Porter, Chief of the Creek Nation, dressed as he appeared on Indian Territory Day in October 1904. Robertson and Studio, prior to December 8, 1904. https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc228722/. Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Porter, who usually wore Euro-American suits, was “playing Indian” as an expression of sovereignty. Just as he had sought to do through the exhibit, he was attempting to defy the “binary terms of authenticity” and assert that Indians could both progress in the modern world and maintain their Indigenous identities. As Philip Deloria argues, throughout American history, white people have “played Indian”—dressing up as and sometimes acting like American Indians—to create American identities, producing and perpetuating stereotypes in the process. But Indians could play Indian, too. Native people sometimes “mimed white-created Indian Others back at white Americans in order to subtly alter perceptions of Indian people.” In Porter’s case, the Plains headdress allowed him to fit the mold of what white audiences imagined as the authentic Indian. It was a risky move, however, because although Indians playing Indian might succeed in redefining stereotypes, they “might also reaffirm them for a stubborn white audience.”Footnote 94 This was exactly why the Vinita Weekly Chieftain, published in the Cherokee Nation by a non-Native editor, reacted negatively to Porter’s actions. “Chief Porter went to St. Louis, decked himself out in feathers and buckskin, had his picture taken and published in the St. Louis Republic and otherwise made himself ridiculous,” the paper complained, emphasizing that Porter probably had not dressed in “such toggery” in decades. The article continued, “What Indian Territory wants above all things, is to show the world that it has gotten away from the age of feathers and tomahawks.”Footnote 95 The editor, and likely many other non-Natives, failed to comprehend Porter’s performance, seeing it as counterproductive to the goal of proving capacity for statehood.

Yet Porter’s main audience may have been other Indians. He brought with him to Indian Territory Day “twelve full-blood Indians,” members of the Creek Council, “said to be opponents of the chief.”Footnote 96 A newspaper in Oklahoma Territory reported, “At the last session of the council they organized against the chief, and it is rumored that this St. Louis trip has a political significance.” “Chief Porter is Crafty,” the headline read.Footnote 97 That day at the fair, Porter channeled the cultural power of performance toward political ends. Porter hoped that the spectacle of Indian Territory Day, his efforts to embody a powerful Native chief, and his indifference to backlash from white settlers would sway his traditionalist opponents to his side. Less than a week after they returned home from the Indian Territory Day festivities in St. Louis, Porter delivered his annual message to the Creek Council and advised separate statehood for Indian Territory.Footnote 98 Although the traditionalists on the Creek Council held firm in opposing any form of statehood, Porter was undeterred and pursued concerted action among the Five Tribes.

By the end of October, Porter and Cherokee Chief William Rogers, who had also attended Indian Territory Day, called for a meeting of the executives of the Five Tribes to pass a resolution for separate statehood.Footnote 99 This resulted in the August 1905 Sequoyah Constitutional Convention, made up of representatives from each of the five nations and some non-Natives. In recognition of his enduring commitment to separate statehood, Porter was selected president. The convention drafted a constitution, which received overwhelming support from voters in a territorial referendum. However, Republicans controlling Congress and the White House did not want to yield any power. Indian Territory was assuredly Democratic, as the territory bordered former Confederate states and mainly attracted white settlers from the South, while Oklahoma Territory leaned Republican, with Black homesteaders the deciding factor against a strongly Republican northern half and strongly Democratic southern half. Political parties remained split according to sectional loyalties, a legacy of the American Civil War. Sequoyah was ultimately rejected not because Indian Territory failed to prove capacity for statehood but because of party politics.Footnote 100 Instead, the Oklahoma Enabling Act passed in June 1906, empowering Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory to form a joint constitutional convention. In November 1907, Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory joined the Union as Oklahoma, the forty-sixth state.Footnote 101

That Porter and Rogers organized the initial meeting so soon after celebrating Indian Territory Day together hints at the possibility that shared conversations and experiences at the fair played a role in the unified separate statehood attempt. While this connection remains only speculative, the exhibit played another more certain role in this final bid for a Native state. When they submitted the Sequoyah Constitution to the U.S. House and Senate, they included the resolutions adopted by the councils of the Creek and Choctaw nations during the 1903 attempt to secure separate statehood. Yet again, the Five Tribes invoked the Indian Territory exhibit to assert their ability to self-govern, citing Native commissioners as “proof” of their efforts to develop the territory.Footnote 102 By this time, the exposition had been closed more than a year. The exhibit remained a touchpoint for the Five Tribes because they had imbued it with political significance from the beginning. They had fused the politics of display with the formal politics of statehood and propelled a local political contest into the national spotlight.

Although Indian Territory was not made its own state, the separate statehood movement had its achievements. Many of the Sequoyah Convention delegates went on to serve in the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention. In drafting Oklahoma’s constitution, they drew heavily from the Sequoyah Constitution, which helped keep the more populous Oklahoma Territory from seizing total control of the future state. A major issue cited by Native nations in their pursuit of separate statehood was protecting their dry territory from the lax liquor policies of Oklahoma Territory. It was therefore a significant win that the convention enshrined prohibition in Oklahoma’s state constitution.Footnote 103 Furthermore, the effort that the Five Tribes put into protecting self-governance paid off when the federal government did not completely dissolve tribal governments as the Curtis Act prescribed. The Five Civilized Tribes Act of April 26, 1906, eliminated most functions of the tribal governments but preserved the office of principal chief in each nation (or governor, in the case of the Chickasaw Nation). Although the office was restricted to a ceremonial role, the fact that the tribal governments were able to continue in any form prevented their total destruction and helped in the restoration of power to the tribal governments during the 1970s.Footnote 104 The separate statehood movement had a lasting impact on state and tribal politics.

As a highly visible project guided and claimed by members of the separate statehood movement, the Indian Territory exhibit played a role in favorable results achieved by the movement. World’s fairs served not only as tools of colonial and imperial hegemony but also as sites for imagining and pursuing Indigenous political futures. Native citizens were able to use this public platform to help prevent unmitigated colonial control. Their exhibit was surrounded by many more that propped up scientific racism and celebrated the “civilizing” impact of assimilationist policies, but participating in the exposition was not a choice made from ignorance of what the fair symbolized. It was an intentional strategy calculated to protect the futures of their nations. As the Curtis Act chipped away at their powers, the Five Tribes had to seek creative means of influencing policy. Participating in the 1904 fair was an especially powerful tactic for extending their political leverage; cultural production freed them to assert their political rights without invalidating their “authentic” Indigenous identities in the eyes of their settler audience. By appropriating the exposition’s narrative of progress and wielding it for their own ends, the exhibit’s Native planners and supporters communicated their right to self-determination in a manner they hoped would be comprehensible to fairgoers. They recognized that their public self-representation, magnified by the prominence of the fair, had the power to drive policy.

That the Native nations of Indian Territory continued to invest their time, energy, and money in the exhibits throughout 1903 and 1904 demonstrates that proposing the state of Sequoyah was not a half-hearted endeavor pursued with the expectation of failure but the culmination of years of hard work and preparation. With separate statehood, the Five Tribes articulated a model for Indigenous self-governance within the confines of U.S. citizenship and membership in the nation. Their ideas represented a novel contribution to unresolved debates over how to integrate remaining western territories into the United States and how to incorporate diverse peoples within the citizenry. Oklahoma statehood closed off this alternative path for the configuration of power relations among the federal government, local authority, and Native nations. It is easy to dismiss the Indian Territory exhibit and the separate statehood movement as minor blips on the road to dissolution if they are evaluated only on how closely the outcome matched the intended goal. Instead, these initiatives must be seen for the possibility they held for the Native individuals involved and for those individuals’ ingenuity in asserting agency within a system designed to steadily strip them of access to political power.