3.1 Human Development and Health

Malaysia’s health development has been part of the wider process of human and other socio-economic progression. This chapter provides the broader context to the Malaysian health system through a brief analysis of socio-economic development and its impact on health risks and conditions. There were also associated health improvements that in turn fostered human development. This analysis provides a macro and concise framework for the more detailed examination in other chapters of the development of the Malaysian health system in terms of its service delivery, related inputs and more detailed outcomes.

Malaysians have made noteworthy socio-economic progress since the country’s independence in 1957, in view of the advantages and challenges of their physical and equatorial environment. As a result of these efforts, Malaysia is now among the countries that have achieved very high human development according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), based on attained life expectancy, education and income per capita (United Nations Development Programme, 2018). Malaysia is also among the group of high- to middle-income countries with a gross national income per capita of $26,190 in 2015 (purchasing power parities, 2015), compared with the substantially lower average of $15,627 for countries in the same income group (World Bank, 2017), and is on the pathway to joining the high-income group of nations.

Malaysia is a good example of a comprehensive approach to development. Since independence, government policies have been progressively articulated in five-year development plans in a holistic manner that deals not only with the economic elements but also other social elements of human development, including health. Thus health interventions are planned and implemented in the context of a range of complementary activities in socio-economic development. They reflect priorities set across the board, including labour force and financial resource constraints, and the steps taken to address them. Therefore, it is essential to examine health advances in conjunction with concurrent socio-economic development that affects the way people live and where, and what they do, with an impact on social organisation, as well as geographical and financial factors that have a bearing on relative access to health services and living conditions.

The progress made in human development in Malaysia has been substantial in terms of the three measures used by the UNDP in its index of human development: life expectancy, education and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. Using 1970 as a basis, life expectancy had increased by 11 years to 75.6 years in 2015, secondary education enrolment more than doubled to 85%, and GDP per capita increased by more than five times to 35,100 Malaysian Ringgit (Table 3.1).

| Year | Human development measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy (years)1 | Education: secondary school enrolment (%)2 | GDP per capita constant prices (MYR 000s)3 | |

| 1970 | 64.4 | 39.2 | 6.2 |

| 2015 | 75.1 | 85.0 | 35.1 |

| 2015/1970 | 1.17 | 2.17 | 5.66 |

1 The average number of years lived from birth.

2 The percentage of children of relevant age attending secondary school.

3 The average gross domestic product (GDP) per capita at constant prices in thousand Malaysian Ringgit (MYR).

Three major phases can be identified in human development since independence. Their expression in health development is as follows:

The first phase, during the 1960s and 1970s, emphasised rural development and capacity building of the health system.

The second phase, in the 1980s and 1990s, was one of consolidating socio-economic transformation and the health system, from a rural setting to rising employment in secondary industries, urbanisation with migration from rural to urban centres and growing health system capacity.

The third phase, in the 2000s and 2010s, has the characteristics of a more developed socio-economic configuration, with growing urbanisation and sustained employment in manufacturing but a larger proportion of people employed in services. Conditions have continued to improve, but growing affluence and more sedentary occupational and recreational activities have led to lifestyles that compromise the rate of health enhancements.

Health status has been closely associated with poverty, and in turn, health services provision has contributed to poverty alleviation (Reference Hammer, Nabi, Cercone, van de Walle and NeadHammer et al., 1995). In addition to socio-economic factors in development during the above three phases, four variables will be used in the analysis to examine the evolution that affected health status in Malaysia: poverty prevalence for social and economic security affecting health status; urban/rural residence for the manner of social organisation and geographical access to health services; rate of safe deliveries for access to and coverage by basic health services; and infant mortality rates as a marker of health status in a relatively young society, even today.1

3.2 Reaching the Poor in Rural Malaysia and Increasing Capacity (1960s and 1970s)

At independence in 1957, about three-quarters of Malaysians lived in rural areas (74%), and close to half of the labour force worked in agriculture (47%), mostly in rubber plantations and rice cultivation. The unemployment rate was estimated at 13%, but it was posited that there was considerable additional disguised unemployment (Reference Fernandez, Hawley and PredezaFernandez et al., 1975; Reference JonesJones, n.d.; Supplementary Table 3.J). Poverty was pervasive, with 51% living below the poverty line on average and 60% living in rural areas (Reference RoslanRoslan, 2001; Supplementary Table 3.D). This was associated with a high population growth rate (almost 3% per year) driven by a high fertility rate of more than 5 live births per woman, which led to a large proportion of the population being under 15 years of age (44%) and a dependency rate of 82% on the working-age population but a relatively low proportion of people aged 65 years and over (3%). However, the high rate of infant mortality (75/1,000 live births) contributed to low life expectancy at birth of only 57 years at that time (Reference Fernandez, Hawley and PredezaFernandez et al., 1975; Supplementary Tables 3.E, 3.H and 3.I). In addition, poor health due to the high incidence of malaria, tuberculosis and other communicable diseases (Reference RoemerRoemer, 1976) affected the productivity of human capital. There is also evidence of malnutrition in children from poor rural areas (Reference McKay, Lim, Notaney and DugdaleMcKay et al., 1971; Reference Chong, Tee, Ng, Kandiah, Hussein, Teo and ShahidChong et al., 1984). The low level of education was another dimension of the quality of human capital: in 1957, more than half the population aged over 14 years (53%) were illiterate in any language (Ministry of Education Malaysia, 1967), with implications for female fertility and maternal and child health associated with the level of education of women.

Few doctors and nurses were concentrated in urban centres in relation to the population (Supplementary Tables 3.K and 3.L) to address the large burden of disease and mortality. There was significant reliance on traditional healers, with services provided by bomohs (healers) and kampong bidans (village midwives) in the Malay tradition. Sinsehs (Chinese physicians) provided herbs and other traditional Chinese medicines, supplemented on occasion by Western-type medicines. There were also a few Ayurvedic practitioners from India. It was not uncommon for care to be sought interchangeably regardless of ethnicity. Although there were reservations about the effectiveness of traditional practices, the household expenditure survey for 1957/1958 indicated that households spent almost as much on traditional medicines with a lower price as they did on more costly Western ones (Reference RoemerRoemer, 1976).

It was in this context that various Malaya and Malaysian2 plans were formulated to address both economic and social development during this first phase. Rural development became a major policy objective in the 1950s and 1960s to address the productivity, income and living conditions of most people in Malaysia. Government development expenditure rose from 3.6% of the GDP in 1956–1960 to 6.8% in 1966–1970 and government revenue from the export of oil rose to 12.6% of the GDP in 1976–1980 (Reference Lee and Chew-GingLee & Chew-Ging, 2017). During 1956–1980, about a third of development expenditure was for infrastructure such as roads, power and communication that enhanced rural and regional transport and communication, and about one-quarter was for agriculture to improve productivity and the income of poor rural populations engaged in rice cultivation, reforming rubber plantations and developing palm oil cultivation in small holdings with improved productivity. A substantial development expenditure that included security (due in part to internal emergency and confrontation with Indonesia over the sovereignty of Sabah and Sarawak) absorbed some 16% of the total government development expenditure during this period. Development expenditure on education and health (which tends to be less than that on security, transport and public works) amounted respectively to about 8% and 2% of the total during this period (Reference PeacockPeacock, 1981; Reference FongFong, 1985; Reference Aslam and HassanAslam & Hassan, 2003).

The importance of health services reaching the poor in rural areas was expressed in the priority given to the following complementary activities (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.):

Training of health personnel and recruitment in rural areas.

Provision of rural health services, including safe water and sanitation.

Prevention and management of communicable diseases.

Improved hospital capacity to support primary care.

Family planning and nutrition supplementation.

This reflected the considerable regional differences in infant mortality that prevailed through the 1960s and 1970s, which were associated with the proportion of people living in rural areas and with levels of household poverty. Accordingly, the state of Terengganu, with 68% of households living in poverty and 73% of its population in rural areas, had an infant mortality rate of 54 per 1,000 live births; Selangor, including Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia’s large urban capital), had a lower proportion of rural population (55%), a lower level of poverty (43%) and a substantially lower infant mortality rate of 30 per 1,000 live births (Reference HasanHasan, 1986).

The efforts made to improve economic productivity resulted in an average GDP annual growth rate of 7.1% in the 20-year period of 1960–1980. However, the large population growth reduced it to a still-helpful rate of 3.7% per head of population (Supplementary Tables 3.A and 3.E). Even though primary industries continued to constitute a large proportion of the GDP (31%) in 1980, the proportion of secondary production almost doubled to 25% of the GDP, with little change in the proportion of services (44%) (Supplementary Table 3.B). Employment saw a substantial decline in the proportion of the population employed in primary industries, mostly in rural areas, from 50% to 39% during the 20-year period and an increase in the proportion of those employed in services from 30% to 40% (Supplementary Table 3.C). Although the majority of the population continued to live in rural areas, greater urbanisation took place, and the proportion of the population living in urban areas increased from 26% in 1960 to 42% in 1980 (Supplementary Table 3.J), with consequences for the mode of living, type of work and conditions and relative ease of access to health services. Further, substantial gains were made in education. By 1967, enrolment among children of relevant age in primary education had risen to 94% and to 52% in lower secondary education, with considerable progress in the education levels of women (Ministry of Education Malaysia, 1967), which is associated with fertility and maternal and child health (Reference HasanHasan, 1986). This was coupled with the increase in the female labour force participation rate from 37% in 1970 to 44% in 1980 and the observed substantial decline in fertility, which was also enhanced by the family planning programme in 1965 (Reference Fernandez, Hawley and PredezaFernandez et al., 1975; World Bank, 2019d; Supplementary Table 3.G).

Development in terms of personnel and rural health facilities made substantial progress during this phase. The number of people per nurse declined about four-fold and that per doctor declined by about half during the 20-year period of 1960–1980 (Supplementary Tables 3.K and 3.L; Chapter 8). Public hospital services were upgraded without an increase in the number of beds per head of population, but their use rose by 43% during the same period (Chapter 5). The proportion of the population served by sewerage rose by about 89% and that with access to safe water increased by about 82% in the 10-year period 1970–1980 (World Bank, n.d.; Chapter 7). The impact on health of the various preventive and management interventions is illustrated by the 29% decline in the incidence of malaria and 96% decrease in the incidence rate of diphtheria in the 4-year period of 1976–1980 (Chapter 6). This progress was achieved with a relatively low total health expenditure. Estimates for 1973 indicated that total health expenditure amounted to only about 2% of the GDP, and that 65% of it was spent in the public sector (Reference RoemerRoemer, 1985; Chapter 8).

During 1960–1980, socio-economic development and changed employment opportunities increased the proportion of the urban population from 26% to 42% in 1980, and poverty levels declined from 49% in 1970 to 37% in 1980. Easier access to health services and increased service provision in rural areas led to greater health services coverage. In Peninsular Malaysia, safe deliveries by professionally trained health personnel rose from 41% to 85% during this 20-year period; as a proxy measure of health improvement in a young population, the infant mortality rate declined by more than half from 69 per 1,000 live births in 1960 to 24 in 1980 (Table 3.2). Life expectancy at birth rose by 8 years to 68 years in that period (Supplementary Table 3.G).

3.3 Transition and Consolidation (1980s and 1990s)

The core development objectives in the 1980s and 1990s were the eradication of poverty, the re-structuring of society and more balanced regional development (Prime Minister’s Department, 1989). The related health policy goals set out in the Fourth to Seventh Malaysia Development Plans were (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.):

Training of health personnel and their engagement to serve the growing population and a better mix of human resources to provide needed services.

Reduction in the disparity of health status among different population groups and areas.

Control of preventable infectious diseases.

Promotion of healthy living environment.

Collaboration in health promotion between the public and private sectors and among agencies.

Improvement in productivity and quality of services.

A major transition took place in Malaysia during these two decades. The population almost doubled from about 14 million to 23 million (Supplementary Table 3.E) in spite of a decline in the average fertility from four to three children per woman (Supplementary Table 3.G). Consequently, the proportion of children aged under 15 years decreased, with a compensating increase in the proportion of working-age people (15–64 years), which reduced child dependency on working-age people from about 70% to 53%, but the proportion of older people aged over 64 years remained low at 4% (Supplementary Tables 3.H and 3.I). The growth in working-age people was accompanied by a major shift in economic activity from agriculture to manufacturing and related employment. Accordingly, employment in primary industries, mostly agriculture, declined from 39% in 1980 to 16% in 2000, and the proportion of people employed in secondary industries (manufacturing and construction) rose from 21% to 36% (Supplementary Table 3.C). The economic transformation provided a wider range of employment opportunities, and the unemployment rate, which had risen to 8% in 1987 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 1989), fell to 3% in 2000 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2001a). Income rose faster than the large growth in population and led to a substantial increase in GDP per head of population at an average annual rate of 3.7% during that period (Supplementary Table 3.A).

However, the rate of progress was upset by the oil crisis in 1979, which affected government revenue and led to fiscal constraints in the 1980s and an economic recession in 1985–1986. Government development expenditure that was still substantially high at 11% of the GDP in 1981–1985 dropped to 6% by 1996–2000 (Reference Lee and Chew-GingLee & Chew-Ging, 2017). As the emphasis on development moved to manufacturing, government development expenditure on agriculture was reduced by about half to 12% of the total in 1981–2000, while investments in infrastructure for roads, communication and power generation continued to receive about one-third (34%) of the total, and investments in industry increased somewhat from 14% to 17%. Government recognition of the importance of the continual improvement of human capital for both economic and social purposes was shown in the rise of development expenditure on education from 8% to 12% and that on health from 2% to 3% (Reference Aslam and HassanAslam & Hassan, 2003). Primary education enrolments became almost universal (97%); secondary school enrolments rose to 65% and that in tertiary education to 26%, with female enrolments, of particular importance to health, being at least on a par with that of men (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2011).

Another aspect of the socio-economic transformation was internal migration to urban areas with employment opportunities. A study carried out in 1989–1990 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, n.d.) indicated that the more rural states lost some of their population due to internal migration, while the more industrialised states gained population that way. As might be expected, internal migrants, both male and female, were younger, and with a higher level of secondary and tertiary education. The majority were Malays from rural areas. By 2000, most people lived in urban areas (Supplementary Table 3.J).

These major socio-economic shifts involved a number of inter-related features that affected population composition and altered health risks. The larger urban population employed in manufacturing and services and the greater participation of better-educated women in the labour force were associated with lower fertility and a rise in the proportion of people of working age, with lower levels of unemployment, higher household income and less poverty. However, occupations required less physical activity, while food intake was enhanced by higher household income and less poverty. As the socio-economic transformation took hold, demographic and epidemiological transitions took place. The epidemiological transition was expressed in terms of a decline in the burden of disease from infectious diseases because of the success of related health interventions, but non-communicable diseases increased with occupational and leisure activities and greater affluence, with an effect on health risks, health conditions and mortality (Table 3.3).

| Cause of death | Age-specific death rates Percentage change for 1982–1990 in age group (years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 1–14 | 15–29 | 30–44 | 45–59 | 60–64 | >64 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Old age (aged over 64 years) | −2.7 | ||||||

| All causes | −36.3 | −37.4 | −14.9 | −8.8 | −11.3 | −17.7 | −2.7 |

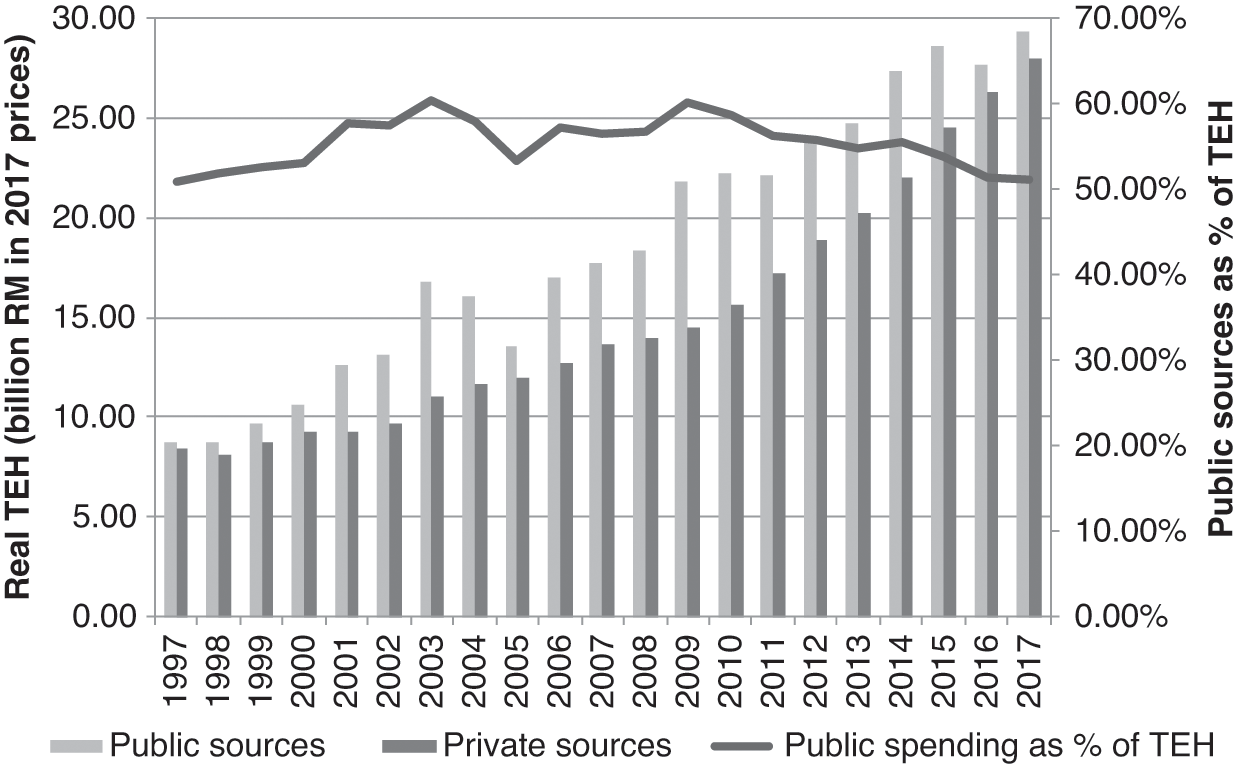

Access to medical services improved during the two decades of 1980–2000 as the number of people per doctor declined by more than half (Supplementary Table 3.K; Chapter 8). The number of nurses and midwives rose in relation to the population, but the number of assistant nurses declined (Supplementary Table 3.L; Chapter 8). Vaccination of infants for a range of communicable diseases reached over 90% coverage in most cases (Chapter 4). Rural household sanitation rose to 98% and access to safe water to 94% (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2002; Chapter 7). The rise in urbanisation and higher household incomes made access to private health services easier. This was associated with an increase in the proportion of doctors in the private sector (46%) (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2002) and almost double the number of people employed in private hospitals and maternity homes (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2001b). This meant that the rate of both outpatient visits and inpatient admissions to public hospitals per head of population either stayed about the same or declined slightly (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 1992; 2002). The transition is reflected in the estimated proportion of visits to doctors that might have been about equal between the public and private sectors in the 1980s but might have been higher in the private sector in the 1990s (Health Policy Research Associates et al., 2013). The rising use of the private sector had an impact on the level of health expenditure in relation to the GDP. A study of health financing indicated that total health expenditure in 1983 amounted to 2.8% of the GDP and that 76% was related to services provided by the public sector (Westinghouse Health Systems, 1985), while estimates for 2000 show that total health expenditure was 3.3% of the GDP and that 54% was financed by the public sector (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2017; Chapter 8). This indicates that the rise in total health expenditure in relation to the GDP in that period might have been mostly from the growth in the private sector.

The socio-economic transformation during 1980–2000, with increasing employment opportunities and migration to urban areas, resulted in most people living in urban areas. It also led to a dramatic drop in the proportion of households living in poverty, from 37% in 1980 to 9% in 2000. Empirical evidence shows that, in addition to its direct impact on health status, the provision of health services by the public sector had considerable distributional effects on alleviating poverty in Malaysia (Reference Hammer, Nabi, Cercone, van de Walle and NeadHammer et al., 1995). Greater coverage of and access to healthcare was facilitated by urbanisation and services rendered by both the public and private sector and the greater use of preventive and other services in the public sector. This was reflected in the increase in the proportion of safe deliveries by health professionals to 97% in 2000. Infant mortality at 7 per 1,000 live births in 2000 had declined to about one-third of that in 1980 (Table 3.4); life expectancy continued to rise by 5 years to 73 years in 2000 (Supplementary Table 3.G).

Table 3.4 Changes in poverty, urbanisation, safe deliveries and infant mortality, Malaysia, 1980–2000

| Year | Households in poverty (%) | Urban population (%) | Safe deliveries1 (%) | Infant mortality rate2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| −28.9 | +20.0 | +11.2 | −17.0 |

1 Those performed by professionally trained health personnel.

2 The ratio of the number of deaths of those aged under 1 year per 1,000 live births.

3 Peninsular Malaysia.

4 The poverty rate is for 1999.

Progress was also made in narrowing the differences between regions, although the differences prevailed. Kelantan, with a high proportion of its population living in rural areas (66%), had the highest infant mortality rate in Peninsular Malaysia, being about twice that of Selangor in 2000 (Table 3.5). However, the difference had been almost three times higher in 1980 (Suleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.).

| State | Infant mortality rate1 | Households in poverty (%) | Rural population (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20002 | Change 19803 | 19992 | Change 19803 | 20002 | Change 19803 | |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |||

| Malaysia | 6.8 | −17.0 | 7.5 | −34.9 | 38.0 | −27.8 |

1 The ratio of deaths of those aged under 1 year per 1,000 live births for 2000.

2 The infant mortality rate and percentage of rural population are for 2000 whereas the percentage of households in poverty is for 1999.

3 Represents the change in the rate from 1980 to 2000 or from 1980 to 1999.

4 Changes for Selangor and Kuala Lumpur could not be estimated because of aggregation of the two in 1980.

5 Labuan was aggregated with Sabah for 1980 and 1999.

6 Birth and infant mortality recorded, especially in Sabah, were of questionable reliability.

3.4 Health in a More Affluent and Urban Society (2000s and 2010s)

The steered socio-economic transformation of Malaysia has led to a more affluent and increasingly urban society. Globalisation of the economy is nothing new to Malaysians. At independence, Malaysia was substantially dependent on rubber and tin production for global markets. Its economy evolved as global markets for different commodities changed to the production of palm oil and crude oil and the manufacture of electronic components and products, again mostly for global markets. Thus Malaysia felt the effects of both the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s and the impact of the global financial crisis in the mid-2000s. Economic growth that faltered in the late 1990s to the mid-2000s regained its strength after 2010, and the GDP per head of population grew at an annual rate of 3.5% in 2010–2017 compared with 2.6% in 2000–2010 (Supplementary Table 3.A).

The Malaysian economy has the features of more developed countries, with a decline in the proportion of the GDP from primary industries, a continuing large contribution from secondary industries and more than half of total production from services (Reference Martins, Guo and SwansonMartins et al., 2018), with similar employment patterns. By 2017, 62% of people employed worked in services, 26% worked in manufacturing and construction and 12% worked in primary industries, mostly in agriculture (Supplementary Tables 3.B and 3.C). The larger proportion of employment in secondary and tertiary industries and the decline in agriculture were associated with the growth of urbanisation to 75% in 2017 (Supplementary Table 3.J).

The importance of training and education to economic activity is reflected in the high level of education of people employed in 2016: no formal education, 3%; primary education, 15%; secondary education, 55%; and tertiary education, 27% (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2017a). In 2017, the net enrolment of people of relevant age in primary education was 99% (female, 99%); secondary education, 75% (female, 78%); and tertiary education, 75% (female, 78%) (Ministry of Education, 2018). The labour force participation rate of working-age people increased to 68% in 2017, with female participation rising to 55% (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2017a; 2018a). The unemployment rate rose only slightly from 3.1% in 2000 to 3.4% in 2017 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2003b; 2018a).

The greater urbanisation, higher education levels and greater female participation in the labour force were associated with a substantial fall in fertility from above replacement level (2.8 children per woman) in 2000 to below replacement level (1.9 children per woman) in 2017. Population growth continued to be high due to the large proportion of young people of reproductive age, but the rate of growth was reduced by half from an annual average of 2.6% in 2000 to 1.3% in 2017 (Supplementary Table 3.E). A feature of this continuing population growth was the increase in the proportion of people other than those identified as ethnic Bumiputra, Chinese or Indian3 from less than 1% (0.5%) of the population in 1980 to 11% in 2017, which indicated a substantial growth in immigration (Supplementary Table 3.F).

The decline in fertility led to a demographic bonus in terms of the rise in the proportion of working-age people from 63% in 2000 to 70% in 2017 and a more productive young population. In the same period, the proportion of children dropped from 33% to a still-high percentage of 24%, while the proportion of older people increased somewhat from 4% to 6% (Supplementary Table 3.H). This meant a fall in the child dependency rate on the working population from 53% in 2000 to 35%, and old age dependency rose from 6% to a still-low 9% during the same period (Supplementary Table 3.I).

Among other priorities, health priorities identified in the three Malaysia Plans covering 2001–2015 were concerned with (Economic Planning Unit, 2001; Ministry of Health Malaysia, n.d.):

Improving accessibility to affordable and quality care and addressing inequalities.

Expanding wellness programmes aimed at improving quality of life.

Promoting co-ordination and collaboration between the public and private providers of healthcare.

Addressing efficiency issues in healthcare delivery.

Strengthening regulatory and enforcement function to administer the health sector.

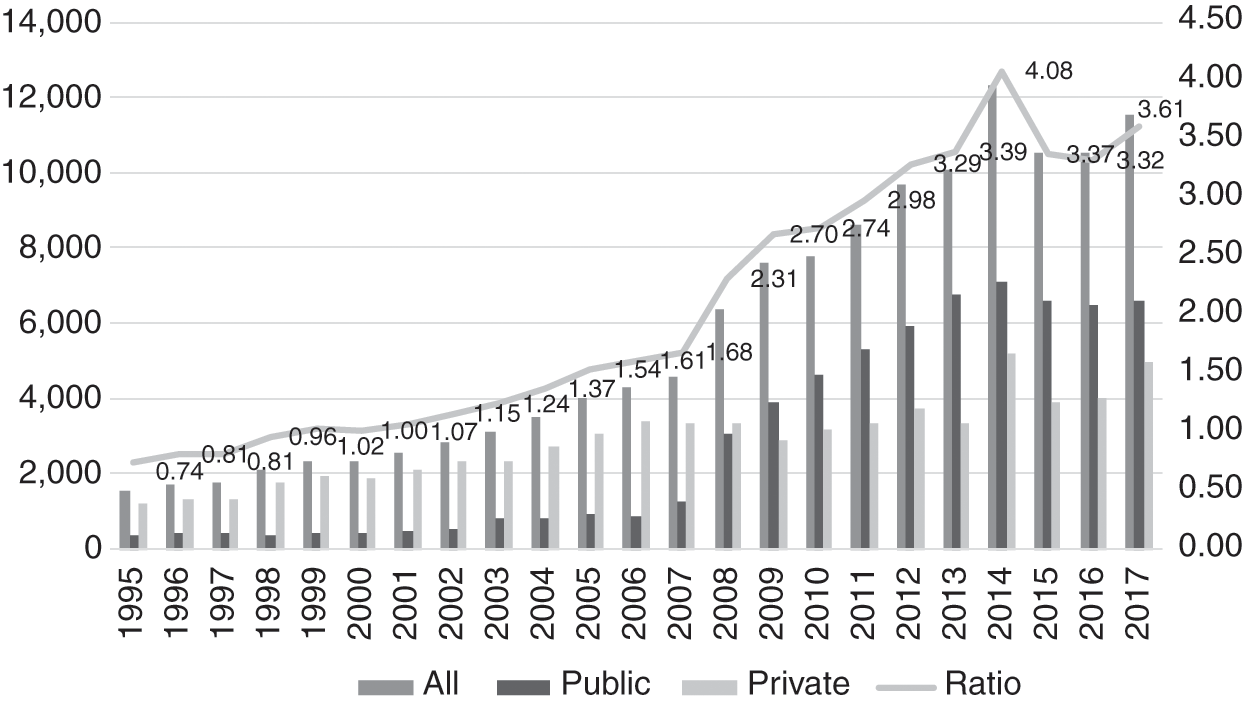

The concern with human resources in the provision of health services was met by a substantial increase in the availability of the two major professional resources. The number of people per doctor was about halved from 2000 to 632 in 2016 (Supplementary Table 3.K), and the number of people per nurse more than halved to 308 (Supplementary Table 3.L). By 2016, an increasing proportion of the larger number of doctors were in the public sector (65% in 2015), and even more so in the case of nurses (76% in 2015) (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018a; Chapter 8).

Prevention of infectious diseases remained a major objective, and child vaccination coverage continued to be high (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018a; Chapter 4). The same was true for access to safe water and sanitation, and the incidence of malaria continued to be low (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018a; Chapters 6 and 7). Another achievement was the eradication of polio. However, the incidence of dengue, often associated with growing urban centres, increased considerably, but better management of those affected resulted in a decline in case fatality rates. A major concern during this period was the threat of HIV/AIDS, which reached its incidence peak in 2002. Prevention efforts led to a fall in incidence by about half in 2016. However, HIV/AIDS affected efforts to control the incidence of tuberculosis, which increased to some extent (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018b; Chapters 4 and 6).

Urbanisation, sedentary occupations and greater affluence are associated with a rise in health risks related to non-communicable diseases, such as obesity (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018b). A study of diet, physical activity and smoking, which have an impact on health risks, such as diabetes, circulatory diseases and lung cancer, indicated that cultural differences resulted in varying behaviours among ethnic groups, and the authors proposed that a more culturally targeted approach was needed for these health risks. It is noteworthy that the study found that access to healthcare also made a difference (Reference Botobara-Yap, Razon-Estrada and BalilaBotabara-Yap et al., 2017). The increasing burden of non-communicable diseases was reflected in the increasing proportion of heart and cerebrovascular diseases from 18% to 21% of all deaths from 2001 to 2017 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2007; 2018b). It is also manifested in the prevalence of diabetes, which increased from 12% to 15% in the 5-year period from 2006 to 2011 (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2013; Chapter 6).

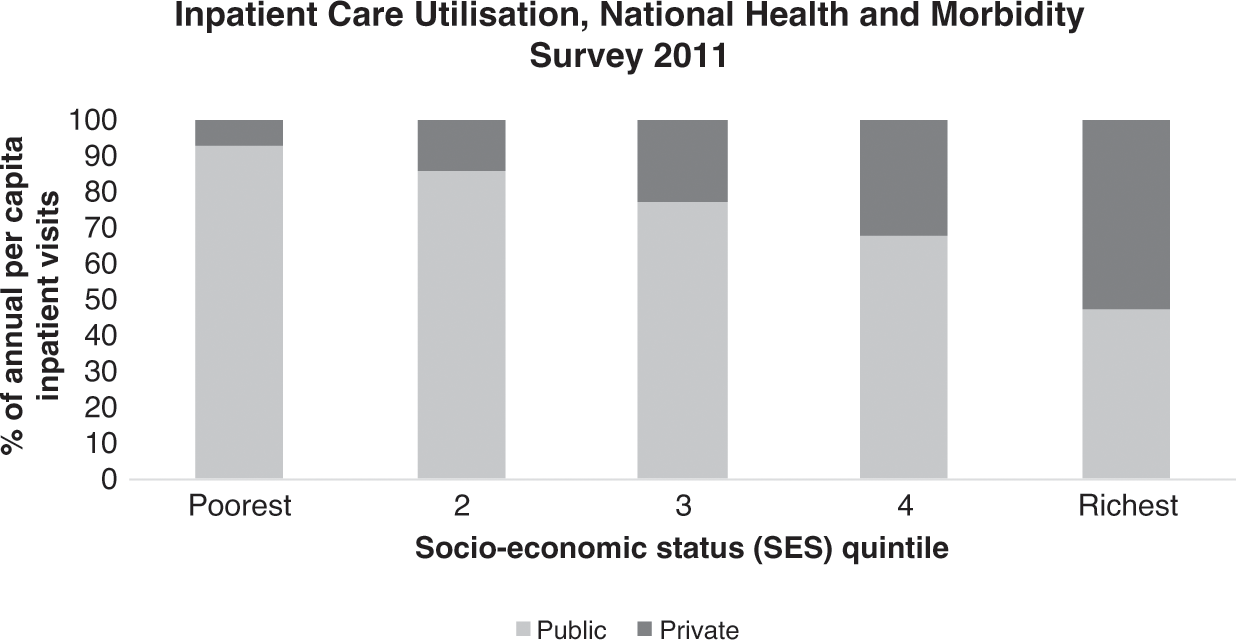

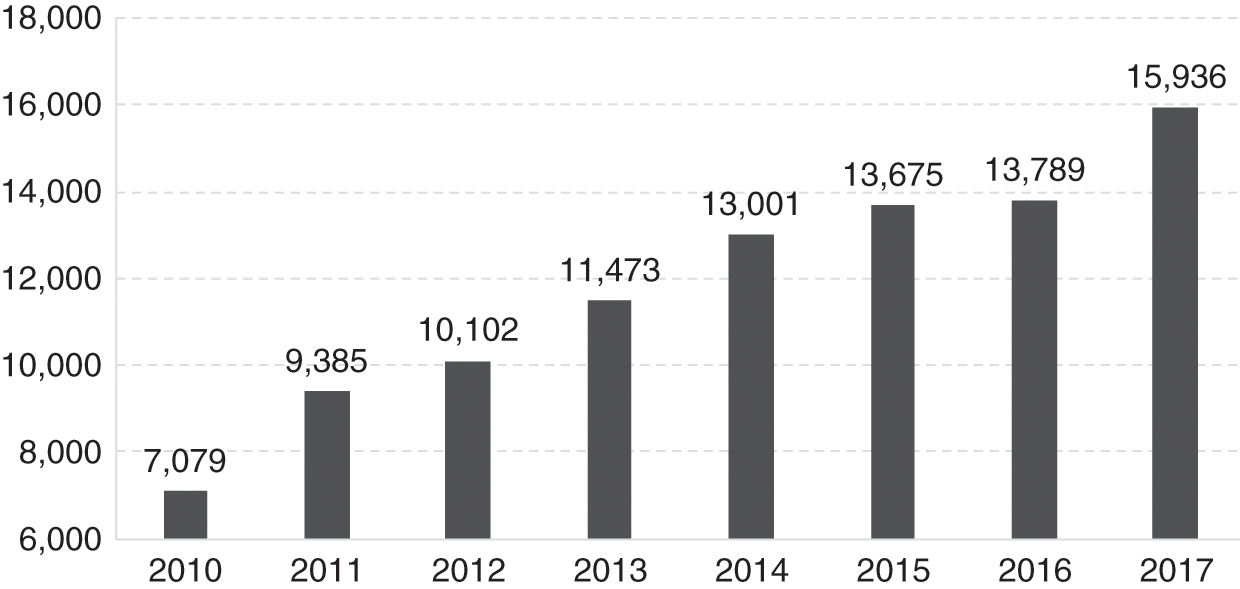

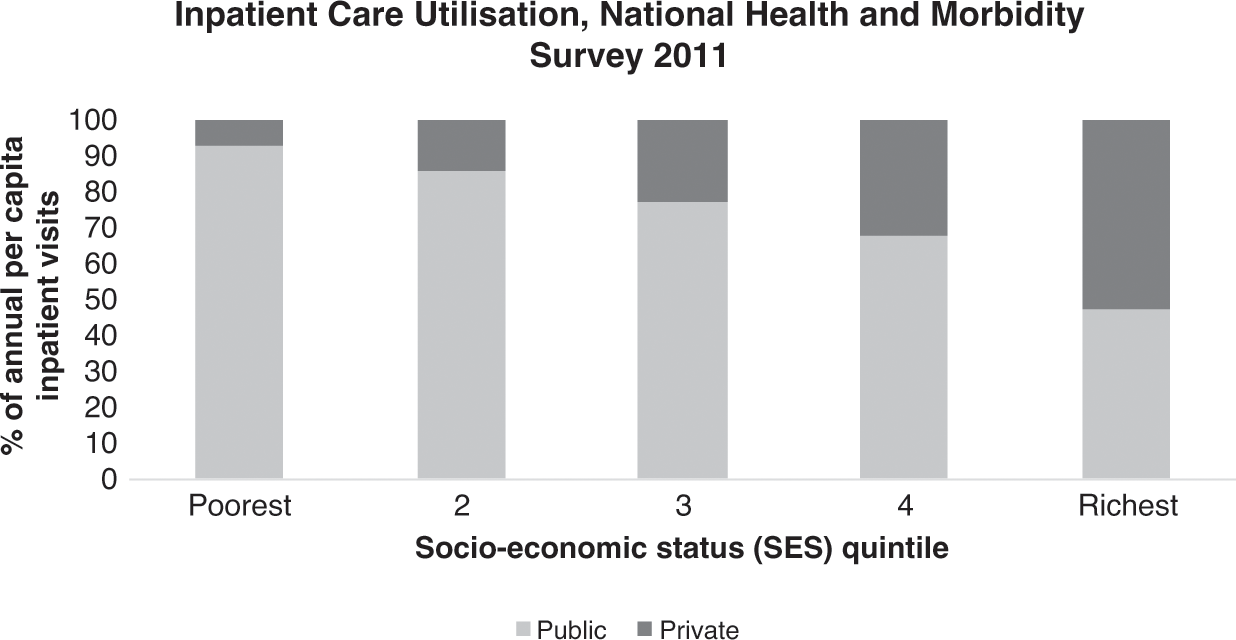

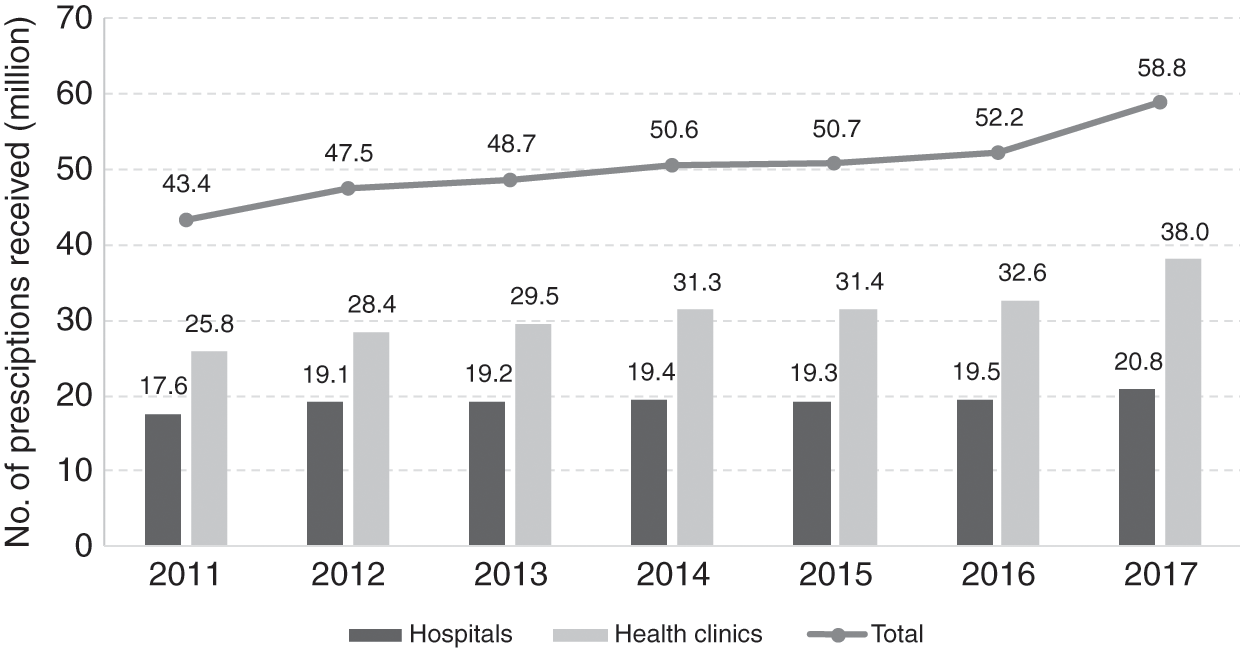

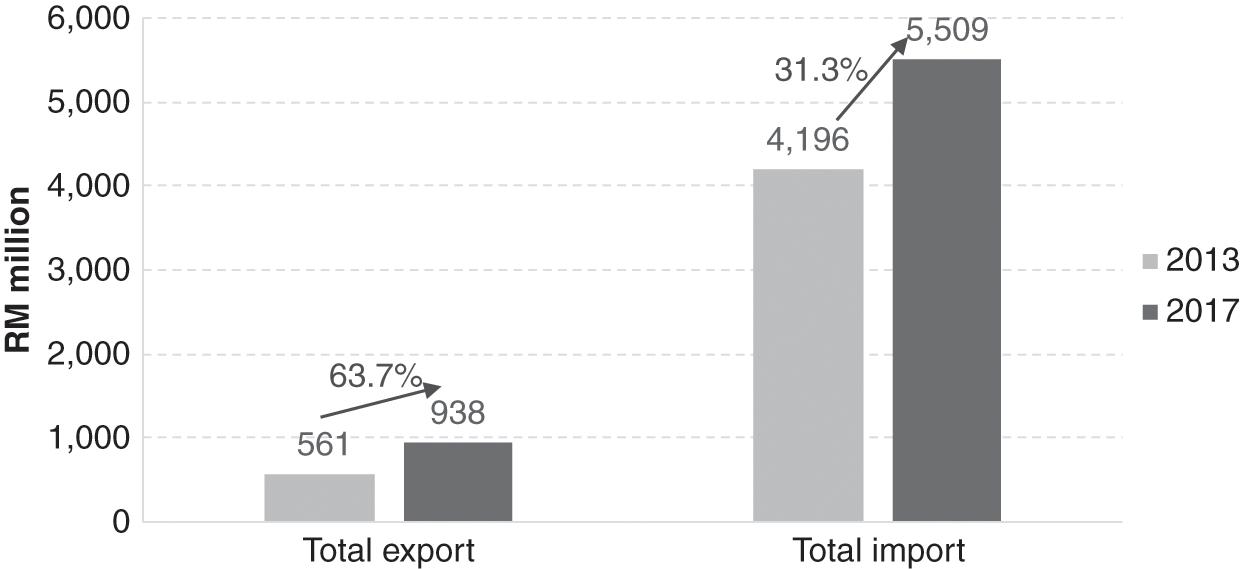

Public hospital outpatient visits increased, but their number per head of population declined, and visits to other public health clinics rose (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018a; Chapters 4 and 5). Evidence from household surveys indicated that the number of visits to doctors in the private sector might have been larger than the number of visits to doctors in the public sector (Health Policy Research Associates et al., 2013). Nevertheless, public sector health services remained the highest provider of both preventive and medical care. The number of people employed in private hospitals continued to grow by more than two-fold in 1999–2015 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2001b; 2017b), and the use of private inpatient care increased. However, admissions to public hospitals also rose substantially (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2002; 2018a; Chapter 5). Despite the rise in private sector provision, the public sector continued to be the largest provider of inpatient as well as preventive and ambulatory medical services. It has been estimated that the above-mentioned considerably higher proportion of both preventive and curative services supplied by the public sector was financed by the public sector at only 51% of total health expenditure in 2015. The private sector, with a considerably lower proportional provision, was financed by 49% of the total health expenditure (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2017; Chapter 9). A possible implication of this, all other things being equal, would be a considerable rise in health expenditure as a proportion of the GDP (4.6% in 2015) if all health services provided were at the expenditure per unit of service prevailing in the private sector.

Continuing economic development and employment opportunities in secondary industries, but especially in services in urban areas, continued to fuel the growth in urbanisation, which rose from 62% in 2000 to 75% in 2016. It was also associated with high levels of employment that improved social and income security further, which helped to alleviate poverty and its associated health conditions. The household poverty rate declined from 8.5% to 0.4% in 2000–2016 (Table 3.6). Although the substantial decline in poverty is not questioned, the actual levels and methodology have been queried in more recent times in view of alternative estimates (Reference RavallionRavallion, 2019). Despite caveats regarding the measurement of poverty, it is apparent that poverty has continued to decline since 1999. Infant mortality was highest in Sabah, which had the highest rate of poverty and a large proportion of its population still living in rural areas, and was lowest in urban Kuala Lumpur, which had one of the lowest levels of poverty in Malaysia (Reference Nair and SagaranNair and Sagaran, 2015; Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2013; 2016a).

Table 3.6 Changes in poverty, urbanisation, safe deliveries and infant mortality, Malaysia, 2000–2016

| Year | Households in poverty (%) | Urban population (%) | Safe deliveries1 (%) | Infant mortality rate2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| |

| −8.1 | +12.8 | +2.9 | −0.1 |

1 Those performed by professionally trained health personnel.

2 The ratio of the number of deaths of those aged under 1 year per 1,000 live births.

3 Poverty rate is for 1999.

4 Poverty rate is for 2009.

As a measure of essential health service coverage and provision in a still relatively young population, safe birth deliveries by professional personnel were almost universal (99.5%) by 2016. Although fertility declined substantially, the momentum from the high proportion of people of reproductive age kept the birth rate at 16 per 1,000 people. A reflection of the need to support the larger number of childbirths is that about a third of admissions (32%) to public hospitals, which provided the most obstetric care in 2015, were related to childbirth and related conditions (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2017a).

In contrast to previous periods, the infant mortality rate did not improve to any significant extent, remaining at about 7 per 1,000 live births during 2000–2016 (Table 3.6). This lack of improvement was also observed for maternal mortality, which remained at around 24 per 100,000 live births during the same period (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018b). Although not reflected in formal records of infant mortality (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2003a; 2016a), analysis of the location of the growing number of non-citizens (10% of the total population in 2017) (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2017c) shows that states that experienced continued improvements in infant mortality, such as Kelantan, tended to have a lower proportion of non-citizens in the population, while those with a higher proportion, such as Johor, experienced either a standstill or a worsening (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2003a; 2016a). This raises the question of potential inaccuracies in the registration of infant deaths of non-citizens.

Notwithstanding the stagnation in the recorded trend towards lower infant and maternal mortality, an achievement was the increase in life expectancy since 1999, in spite of the threat of HIV/AIDS and risks from more sedentary occupations and affluent lifestyles: life expectancy rose by more than 2 years between 1999 and 2017 (Table 3.7).

| Age (years) | Life expectancy (years) | Change in years 2017–1999 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2017 | |||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The potential for further improvements in health status and life expectancy is suggested by studies of avoidable deaths (Ministry of Health Malaysia & Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 2016) and potential years of life lost due to premature mortality and disability (Institute of Public Health, 2017).

These studies point to the potential gains from improvements in occupations and lifestyles that affect mortality and disability from non-communicable diseases, as well as better identification and management. Injury from traffic accidents and other causes is another major area for potential gains. The importance of mental health is also apparent. The research also indicates the continuing importance of preventing and managing infectious diseases (Table 3.8).

Table 3.8 Burden of disease and injury, Malaysia, 2014

| Cause/disease | DALY1 | YLL2 | YLD3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of total | |||

|

|

|

|

| Other | 25.6 | 18.1 | 38.0 |

| All causes/diseases | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Number of years lost | 4,993,000 | 3,099,000 | 1,894,000 |

3.5 Progress and Challenges

This chapter provides a concise and macro analysis that places salient features of health development in its socio-economic framework as a basis for the following chapters, which address the various components of the health system and their complementary contributions to health outcomes.

Health has been an integral and important part of Malaysia’s socio-economic and human development that has aimed at alleviating poverty, enriching human capital, improving living conditions and enhancing health status.

Strategies have been articulated in five-year development plans in which health development has played a vital role in conjunction with education, employment and living conditions. These strategies have evolved as the success of rural development has taken hold and economic development has provided employment opportunities in secondary industries, with growing urbanisation and an increase in related living conditions. The health system’s success in preventing and managing communicable diseases has led to an epidemiological transition that has improved health status but that has made it more dependent on the control of the non-communicable diseases characteristic of more developed, urban and affluent societies. Accordingly, progress has improved health, but it has also created new challenges to continued success in addressing the risks of infectious diseases while strategies and means of tackling the threats posed to wellbeing by the burden of non-communicable diseases are being developed.

3.6 Key Messages from Malaysia’s Experience

3.6.1 What Went Well?

The provision of healthcare can be an important factor not only for the improvement of health status but also for the quality of human capital, its productivity and the alleviation of poverty.

Poor people cannot afford to pay for health services; for them, services need to be free of charge.

Market mechanisms did not meet the health needs of most of the population, especially those in rural areas, and public intervention was required.

Social change, urbanisation and economic development alleviate some health problems but give rise to others.

3.6.2 What Did Not Go So Well?

Fragmentation of responsibility between various agencies significantly impacted health. Recognition and management of fragmentation varied.

The health system is constrained in its ability to deal with some politically charged issues, such as undocumented migrant groups.

3.6.3 Trends and Challenges?

The continued growth of the private health sector and rising health expenditure will be a challenge for the future development of healthcare.

4.1 Introduction

The term ‘primary health care’ (PHC) has been operationalised in a variety of ways since it was first coined as part of the historic Alma Ata Declaration (Box 4.1). In this chapter, we operationally define PHC to cover the ‘first level of contact of individuals, the family and community with the national health system’ and ‘reflect(s) and evolve(s) from the economic conditions and sociocultural and political characteristics of the country’. The elements of PHC we will focus on include ‘education concerning prevailing health problems, … maternal and child health care including family planning and immunization, and appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries’. Other aspects of PHC, such as safe water and basic sanitation, prevention and control of locally endemic diseases, and provision of essential drugs, are covered in other chapters.

Box 4.1 Excerpts from the Declaration of the Alma Ata International Conference on Primary Health Care, September 1978

Primary health care is essential health care … made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford.

It is the first level of contact of individuals, the family and community with the national health system … and constitutes the first element of a continuing health care process.

Involves, in addition to the health sector, all related sectors and aspects of national and community development, in particular agriculture, animal husbandry, food, industry, education, housing, public works, communications and other sectors; … and demands the co-ordinated efforts of all those sectors.

Sustained by integrated, functional and mutually supportive referral systems, leading to the progressive improvement of comprehensive health care.

This chapter explores the development of PHC during the 60-year period after Malaysia achieved independence (1957–2018). The development process is viewed in the context of the interaction of various components of the health system, as well as the interactions with other sectors and the influence of international movements. Two distinct phases of development are evident, as described in Sections 4.2 and 4.3.

4.2 The First Phase of PHC Development (1960s–1990s)

4.2.1 Drivers and Contexts

At independence, about 75% of the population lived in rural areas, and almost half the population lived in poverty (Reference Mohd Ashad and ShamsudinMohd Ashad & Shamsudin, 1997). The ethnic composition reflected the urban–rural divide, with ethnic Malays being largely rural, ethnic Chinese largely urban and ethnic Indians largely in the rubber estates. Maternal and child mortality was high, nutritional status was poor and the incidence of infectious diseases was high. Table 4.1 provides a glimpse of Malaysia’s health status at independence and its evolving status during the subsequent 30 years.

Table 4.1 Health indicators in Malaysia, 1957–1990

| 1957 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life expectancy at birth, male (years) | 55.8 | 61.6 | 66.4 | 68.9 |

| Life expectancy at birth, female (years) | 58.2 | 65.6 | 70.5 | 73.5 |

| Maternal mortality ratio per 1,000 live births | 2.81 | 1.62 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births | 73.01 | 43.82 | 23.8 | 13.1 |

| Toddler mortality rate per 1,000 population aged 1–4 years old | 8.91 | 5.02 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

1 1956–1960

2 1966–1970

The PHC system developed for Malaysia was built on the healthcare system inherited from the British colonial system. It consisted of outpatient clinics attached to hospitals, a few dispensaries and infant welfare centres provided by the government, and private sector clinics operated by doctors (general practitioners, or GPs). Almost all of these services were in urban areas. This healthcare system evolved from the requirements of the expatriate governing staff, that is, the more educated and affluent urban population.

The predominantly rural population depended on practitioners of traditional medicine, while workers in the larger rubber estates depended on estate clinics provided by employers. However, four years prior to independence, the country introduced a service to serve the rural population, which evolved into the Rural Health Service (RHS) in 1956, just before Malaysia gained independence (Reference RudnerRudner, 1972; Reference IsmailIsmail, 1974; Reference Wong, Ng and SuJ. H. W. Wong et al., 2019).

Independence brought into power an elected coalition of ethnically based political parties, led by the ethnic Malay political party. Unsurprisingly, the political focus shifted to prioritise rural communities to reflect the location of strong Malay support. The major thrust of development was to achieve socio-economic transformation by developing the country’s basic rural infrastructure, modernising agricultural production in rural areas and improving education and health (Federation of Malaya, 1960; Reference RudnerRudner, 1972; Reference Lee and LeeLee & Lee, 2017). Infrastructure development was an integrated approach that included rural roads, drainage and irrigation, schools and clinics (Reference Mohd Ashad and ShamsudinMohd Ashad & Shamsudin, 1997). Planning and development was co-ordinated by the Economic Planning Unit in the Prime Minister’s Department, and the progress of all elements within each administrative district was monitored in an integrated fashion through a ‘Red Book’ that commanded the attention of politicians and civil service administrators at national, state and district levels. The RHS was a major component of this integrated development, such that a district would receive an integrated package that increased physical access to basic education and healthcare, while parallel initiatives addressed its economic needs.

4.2.2 The Rural Health Service

The RHS was government funded. A basic RHS unit served 50,000 population. It consisted of a main health centre (MHC), 4 sub-centres (HSC) and 20 satellite midwife clinics, each with an attached residential facility for the midwife (MCQ). This basic unit was designed to provide ‘integrated curative and preventive health services’ (Reference JayasuriaJayasuria, 1967). Table 4.2 illustrates the services and notional staffing pattern of the basic RHS unit. The number of rural health facilities increased significantly between 1960 and 1980 (Table 4.3).

| Facility | Services | Notional staffing pattern |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Health sub-centre (HSC, 10,000 population) |

|

|

| Midwife clinic and quarters (2,000 population) | Domiciliary midwifery | Midwives (with supervisory nurses from MHC or HSC) |

During the first 10 years, the major challenges included difficulty in matching the rate of facility construction with that of population growth, inadequately trained staff for facilities that had been completed, and prevailing cultural beliefs and taboos that hindered service utilisation. After 15 years of development, by 1975, the facility-to-population ratios showed that only 50% of population coverage targets had been achieved. A community survey showed that 24% of the rural villages in the survey areas were ‘underserved’ (Reference NoordinNoordin, 1978). To increase access, the static facility-based services were supplemented with mobile clinics-cum-dispensaries that travelled by road or river, and dental clinics funded by the government, all providing free access to the population (Reference IsmailIsmail, 1974; Reference Tate Abdullah, Khoo and GabrielTate Abdullah et al., 2005). These teams visited remote villages and provided a PHC package consisting mainly of curative, MCH and immunisation services periodically.

4.2.3 The Influence of the Alma Ata Declaration on the RHS: Community Mobilisation, Enhanced Intersectoral Co-ordination, Referral Systems

By the time of the Alma Ata Declaration (1978), Malaysia had already adopted many of the basic concepts of the Declaration. The serving Director-General of Health, Dr Raja Ahmad Noordin, stated: ‘Malaysia viewed PHC as an extension to its existing health care services’ (Reference NoordinNoordin, 1978). The major contribution of Alma Ata was to provide a fillip for the conceptual enhancement of PHC services by spurring the introduction of community mobilisation, enhancing inter-sectoral co-ordination and strengthening referrals to and support from hospitals (secondary healthcare) (Box 4.2).

Use of trained allied health personnel (particularly nurses and midwives) instead of reliance on doctors. Infrastructure development quickly outstripped the availability of human resources. Rapid but strictly regulated training of nurses and midwives, with registration, defined roles with relevant competencies, and appropriate deployment was a success (see also Chapter 8).

Partnerships with traditional birth attendants (TBAs). In the Malay communities, TBAs (bidan kampung) were influential. In 1967, about 3,000 TBAs conducted an estimated 47% of the 174,000 deliveries (Reference PengPeng, 1979). In some areas, the percentage could reach 80% due to both the shortage of midwives and the belief system of the community (Reference Ali and Howden-ChapmanAli & Howden-Chapman, 2007). Recognising the key position of TBAs in rural communities, the Ministry of Health introduced a training programme for TBAs in 1965 (Suleiman and Jegathesan, n.d.) to change their role. They would recognise the danger signs of pregnancy and childbirth, avoid harmful practices and conduct home visits to encourage women to utilise midwife clinics and health centres for antenatal and postnatal care. They also provided support to certified government midwives during home deliveries. The TBAs were allowed to continue to perform harmless traditional practices such as postnatal massage.

Community mobilisation. Several parallel thrusts mobilised community support. Health officials took advantage of the system of village development committees established by the rural development programmes to mobilise the support of the penghulu (village headman) and his committee for various health issues (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003). Women’s development programmes provided entry points to raising awareness and providing practical avenues for better child-rearing and nutrition. The school health programme provided the vehicle for mobilising school children not only to understand and improve their own lifestyle but also to influence their parents’ health behaviour.

Partnerships with other public sector agencies with grassroots presence. Police posts in rural villages had the function of issuing birth certificates and burial permits. Midwives and nurses obtained data on births and deaths in their districts from the police. Similarly, police communications systems (radios) provided the means for front-line health staff to call for ambulances and assistance during medical emergencies.

Dr Noordin spearheaded community mobilisation to make it an integral complement to expanding health services. Additionally, facility expansion was accelerated such that the RHS configuration was modified to extend the coverage of the basic unit to serve a population of 20,000. Staffing profiles changed accordingly. Emulating the successful experience in one state (Sarawak), midwives were upgraded to become rural (community) nurses and given a wider scope of responsibility (Chapter 8). Accelerated training of nurses and midwives enabled rapid upgrading of the quality of services. Simultaneously, community mobilisation took several forms, with active efforts to encourage communities and families to promote health, prevent illness and utilise health services appropriately. Health staff became focal points for organised community efforts, as exemplified in the rural sanitation programme (Chapter 7). Nursing and midwifery staff gained entry to male-dominated village development committees by working in partnership with sanitation staff. This approach enabled them to promote safe childbirth by sensitising communities to the danger signs in childbirth and pregnancy and encouraging the acceptance of prompt medical intervention to save the lives of mothers and babies. Pregnancy care included supervision of childbirth at home by trained, certified midwives, followed by 10 days of daily postnatal home visits that enabled the visiting health staff to build a rapport with the family and the community while establishing breastfeeding and healthy nutritional habits (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003).

Inter-sectoral co-ordination became a part of service delivery as well as infrastructure development. Child health included growth monitoring, oral re-hydration techniques, breastfeeding, immunisations, food supplementation, female literacy and family planning. Partnership with rural women’s development programmes enabled health staff to raise awareness of hygiene and nutrition. Health topics were integrated into school curricula through interagency co-ordination between the Health and the Education Ministries, and school visits by nurses and dental nurse teams brought basic screening, referral and simple treatment to the doorstep of the expanding school-enrolled population. Partnership with traditional birth attendants (TBAs) reduced unsafe childbirth while giving the TBAs a continuing role in supporting birthing women (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003). Nutrition demonstration sessions by nurses in rural clinics gained popularity. The Applied Food and Nutrition Programme, implemented in districts with high levels of malnutrition, is an example of a partnership with the agriculture, rural development and women’s empowerment initiatives.

Regional disparities in social status and poverty led to targeted poverty reduction programmes. These programmes included initiatives for better access to healthcare and for addressing childhood malnutrition in disadvantaged areas. The prevalence of childhood malnutrition was used as a surveillance tool, while the prevalence of undernourished children was a criterion for identifying low-income families to receive food supplementation as well as assistance with education, housing and employment (Economic Planning Unit, 2004).

Another influence of Alma Ata was to highlight the health needs of remote populations, including the indigenous people (Orang Asli), who had limited access to transport to and communication with healthcare facilities. Mobile teams had to travel over unsealed roads, by river and on foot to serve these communities periodically.

The effectiveness of these measures, in combination with the broader socio-economic development issues discussed in Chapter 3, is evident, for example, in the rising levels of childbirth attended by skilled birth attendants, immunisation coverage and declining maternal and child mortality (Table 4.4) (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). The proportion of deliveries by trained personnel increased from 77.2% (Peninsular Malaysia) in 1975 to 95.2% (Malaysia) in 1996 (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). Referral systems were established particularly for maternity and for infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis (TB). When nurses based in rural clinics referred patients with obstetric problems to hospitals, these patients were given priority and prompt attention. Pregnant women and young children carried personal health cards displaying their pregnancy and healthcare information, thereby facilitating information exchange between PHC and secondary levels of care (United Nations Development Programme, 2005; Reference AwinAwin, 2011). The major communicable disease control programmes established similar referral systems (Chapter 6). The parallel development of rural roads and the provision of ambulances stationed at the MHCs facilitated the movement of referred patients, thereby supporting the referral system. This service delivery system in turn enhanced the credibility and acceptability of health services for the rural population. Senior obstetricians who served in public sector hospitals during that period freely attributed the decline in maternal death to the sterling efforts of rural-based nurses and midwives in identifying complications of pregnancy and childbirth and getting patients to hospital in time for effective interventions (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003).

| 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of delivery | |||

| Government hospitals | 30.01 | 43.91 | 59.1 |

| Other medical institutions | 11.41 | 10.71 | 16.1 |

| Home deliveries | 58.61 | 45.41 | 24.8 |

| Immunisation coverage | |||

| Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) (infant) | 46.6 | 88.2 | 98.7 |

| Diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus (DPT) (3rd dose) | 15.0 | 67.0 | 92.0 |

| Polio (3rd dose) | 15.0 | 72.0 | 91.5 |

| Measles (infant) | 10.0 | 20.0 | 69.6 |

1 Peninsular Malaysia only.

4.2.4 PHC in Urban Areas

Public sector.

During the first three decades after independence, the ambulatory health service component of PHC in urban areas was provided by a combination of government-funded public services, the private sector (funded through out-of-pocket expenditure by users) and non-governmental organisation (NGO) services supported by civil society and government grants. There was very little co-ordination across these sectors. However, these services are collectively credited with raising awareness and acceptance of allopathic medical interventions, particularly among those who had relied mainly on traditional remedies and were steeped in cultural beliefs that were obstacles to the use of effective healthcare.

The public sector hospitals each had outpatient (ambulatory) services that provided walk-in care mostly geared to acute episodes of illness, as well as accident and emergency (A&E) services that were available 24 hours a day. In the larger hospitals, doctors aided by hospital assistants (later re-named medical assistants) were backed by pharmaceutical services (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). These services provided referrals for admission and specialist care when needed. Almost all of these hospital-based outpatient services were confined to curative care, except for pregnancy, for which antenatal and postnatal clinics provided counselling and services, including that for family planning. Additionally, in the larger urban configurations, the local authority (such as the city council) provided maternal and child health services through a network of clinics. These services predated independence and were the prototype that was later used by the RHS for maternal and child health services. All of these services were provided for nominal or no fees, and utilisation rates in ambulatory facilities were very high, resulting in queues and long waiting times. During the third decade post-independence (the 1980s), the state of the overcrowded, understaffed services began to cause concerns about the quality of care. This contributed to the genesis of the Quality Assurance initiative (see later in this chapter and Chapter 5).

Private sector.

The private sector complemented the public sector in urban areas. Medical doctors (GPs) owned and provided healthcare, including dispensing medication through small clinics that operated from modest premises. Most were in ‘shop houses’, that is, two- or three-storeyed premises with the clinic on the ground floor. The higher floors sometimes served as short-stay hospitals for patients and came to be known as nursing homes or as private hospitals. Such premises were flanked by other shops. Most patients paid a fee for the service, which was generally very low, affordable and popular with the urban population. They received ‘one-stop’ care by the doctor, sometimes assisted by trained nurses or medical assistants; medication was dispensed on the spot, and minor surgery was performed on the premises.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

NGOs played a small but very significant role in the development of PHC in urban areas. Some NGOs, such as St John Ambulance and Red Crescent, filled gaps in the services provided by the public sector. Others, such as the family planning associations (FPAs) (Box 4.3) and several associations related to special needs, such as impaired hearing, vision and disabilities arising from illness (e.g. leprosy) or genetics, provided small-scale models of care and strong advocacy that served to mobilise civil society to recognise unmet needs. They established partnerships with the public sector, which provided financial grants. For example, the FPAs received an annual grant of RM 200,000 from the government from 1962 until the early 1980s (Reference Tey, Robinson and RossTey, 2007). In later years, when capacity grew, the public sector took over many of these services and used the care models developed earlier by the NGOs.

The FPAs (now known as the Federation of Reproductive Health Associations, Malaysia, or FRHAM) were largely led by prominent obstetricians and personalities active in civil society. They had the ear of policymakers, although the services they provided were limited mainly to small clinics situated in urban MCH clinics and hospital postnatal wards. The uptake of contraceptives was not impressive. The West Malaysia Family Survey conducted in 1966 found that the contraceptive prevalence rate was only 8.8% (Reference Ahmad, Tey, Kamarul Zaman, Muhd Sapri, Abdul Manaf and YeohAhmad et al., 2010). Advocacy and the service models used by the FPAs contributed to the establishment of the National Family Planning Program under the First Malaysia Plan in 1966 to improve families’ health and welfare and promote national economic development. The programme was expanded and integrated into RHS in the mid-1970s to serve rural and remote communities. The rapid expansion of the MCH and FP services have been a major factor in lowering the infant mortality rate across the country (Reference Pathmanathan, Liljestrand, Martins, Rajapaksa, Lissner and de SilvaPathmanathan et al., 2003).

Traditional and complementary medicine (TCM).

Although traditional practitioners were and continue to be widely available, there is little information about them. They were not registered, and their practice was not regulated. More recently, there has been stronger oversight of the products they use, and this is discussed in Chapter 11.

4.3 The Second Phase: The Continuing Journey towards Integrated PHC Services (1990–2017)

4.3.1 Drivers of Change

Economic growth continued over the following 30 years, although there were a number of setbacks, including the Asian financial crisis. The population became increasingly urban, reaching almost 70%, and the proportion of teens and young adults increased, followed by an increase in the number of elderly people (Chapter 3). Lifestyles and health-related behaviour, particularly around food and physical activity, began to change. For example, during the 1990s, tobacco smoking and drug addiction were major concerns, while in the 2000s, the obesity epidemic took centre stage (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.). As people became increasingly well-connected with the world through media and travel, public expectations of healthcare increased.

Rising healthcare costs competed with other priorities in the national budget and increased pressure on the health sector to consider alternate approaches for healthcare financing (Chapter 9) and cost containment. The voices of civil society became stronger, with a growing dichotomy between conservative and liberal value systems. This generated debates and tension on many health-related issues, such as reproductive health and HIV/AIDS. Additionally, international pressures, first towards achieving Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and subsequently re-aligning towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), influenced national health goals (Chapter 6, Case Study 6.1).

All of these interacting forces were drivers that influenced health policy and the evolution of PHC, first towards the provision of a greater range of services to cater for new and emerging needs; second towards better integration between services. Integration and co-ordination were needed to remove institutional barriers between the multiple healthcare services that catered to any particular family and to focus on providing health services to meet the needs of people within their families and communities. The rapid urbanisation also required different modalities from rural settings for the provision of integrated PHC.

The Seventh Malaysia Plan (1996–2000) marked a change for PHC with the establishment of a new PHC division in the Ministry of Health (MoH) (Economic Planning Unit, 1996). The evolving PHC services during this period had two major characteristics. First, in the public sector (mainly MoH services), there was convergence of the hitherto separate services for promotional-cum-preventive health provided at health centres and the curative outpatient services provided by MoH hospitals and health centres. Second, in the private sector, serious stresses emerged in services provided by GPs, associated with issues of financing and competition from public-sector clinics and by specialist practitioners who also provided primary care (Chapter 4, Case Study 4.2).

4.3.2 PHC Services in the Public Sector

The overarching goal of the public sector was to achieve equitable access to more comprehensive primary care. Three threads of interlinked thrusts towards this goal are discernible, namely:

Expanding the scope of PHC services to encompass additional age groups and health needs.

Integrating preventive-cum-promotional services with curative services to address segmentation and compartmentalisation and provide seamless care for individuals, families and communities.

Improving the quality of services to respond better to expectations in the community and professional groups.

4.3.2.1 Expanded Scope of Preventive PHC Services in the Public Sector

During the 1990s, responding to demographic and morbidity trends, the preventive and health promotional services provided by health centres expanded to include additional age groups (adolescents, adults, women’s and workers’ health, the elderly, children with special needs) and health problems, such as mental health and screening for iodine deficiency and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, while the national childhood immunisation programme expanded to include measles, mumps and diphtheria, and Haemophilus influenzae (Reference Suleiman and JegathesanSuleiman & Jegathesan, n.d.).

The clinic-based services were complemented by community-based programmes. The nutritional surveillance of children and pregnant women conducted in 1988 provided valuable input to the national poverty reduction initiatives and rehabilitation efforts (National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition, 2006). The Food Basket Programme (also known as the rehabilitation programme for malnourished children) for children with poor nutritional gain continued to reach out to poor communities (National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition, 2006). Clinic-cum-community services were also initiated to support anti-tobacco smoking efforts, which included smoking cessation clinics. The health clinic advisory panels (panel penasihat), with local community representatives, worked with health staff on four major areas: healthy ageing, advocacy for immunisation, dengue control, and diabetes and overweight management (Reference Mustapha, Omar, Mihat, Noh, Hassan and Abu BakarMustapha et al., 2014).

Simultaneously, the hitherto rural health services gradually increased their coverage to include urban areas in response to demands from local authorities that had little interest in providing services that did not generate revenue. This required organisational re-structuring, including the transfer of authority, staff and some physical facilities from the local authority to the national MoH, particularly in the metropolitan cities of Penang, Melaka and Kuala Lumpur. It also paved the way subsequently for easier integration of preventive and curative services.

Gaps in and limitations to expansion.

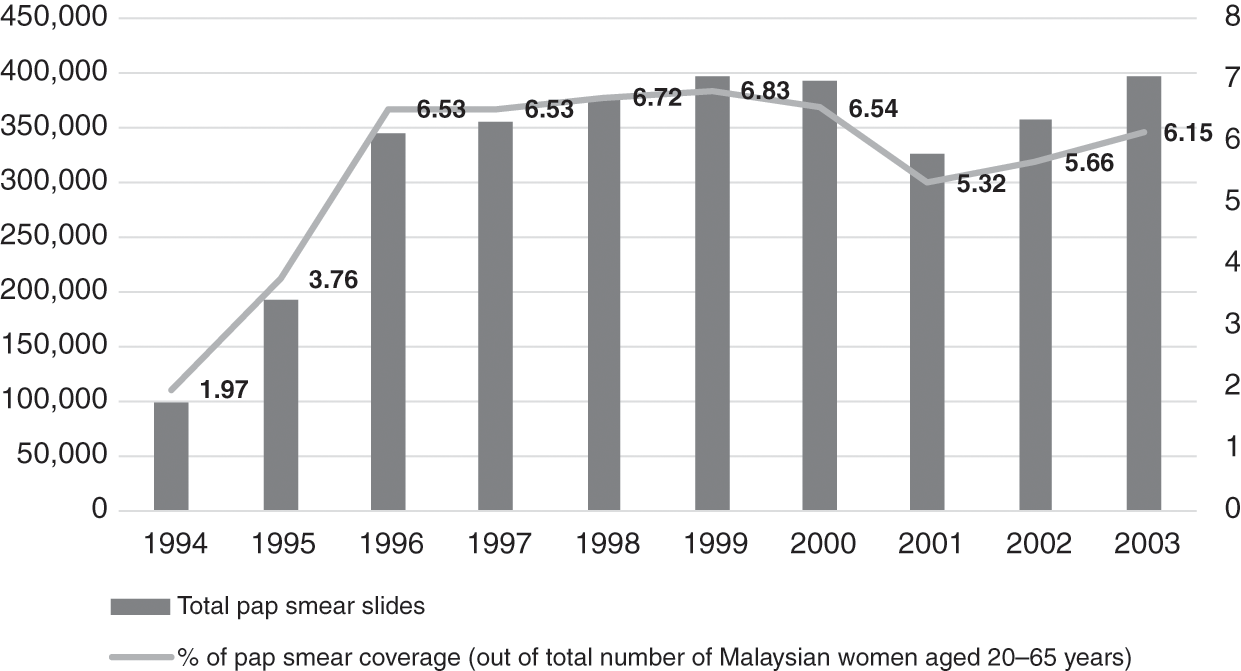

Financial and human resources constraints limited some of the service expansion. For example, cervical cancer screening had already been planned to incrementally cover larger sections of the target age group, but laboratories could not cope, and the turnaround time was slow. Screening reached only 6% of eligible women (aged 20–65 years) between 1996 and 2003 (Figure 4.1) (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2005), and follow-up call services were inadequate (Reference Wong, Wong, Low, Khoo and ShuibL. P. Wong et al., 2008). Also, other components of the health system interacted with PHC services in the public sector to initiate, facilitate or limit the expansion of PHC services. Examples are summarised in Box 4.4.

Examples of Limiting Factors

Finance: Dictated the speed and influenced the scope of expansion. While new programmes were added, some existing programmes, such as family planning and cervical cancer and breast cancer screening programmes, failed to gain traction.

Workforce: Upgrading the competencies and recruitment of new categories with different competencies needed, such as finance, training and managerial support. For example, the lack of trained staff hampered the ability to provide rehabilitation, occupational therapy, home visits and home care nursing services for the elderly.

Examples of Enabling Factors

Medical products and technology: Additional affordable vaccines (measles, mumps and rubella (MMR), hepatitis B, human papillomavirus (HPV)) and the availability of simple field tests (G6PD and hypothyroidism screening) enabled the expansion of services. Staff training and financial support enabled this expansion.

Health information: Nutritional surveillance identified anaemic pregnant women and malnourished children and enabled the provision of food baskets for them as part of multi-sectoral poverty reduction; Teleprimary Care enabled better management of diabetes and hypertension by providing data for targeted monitoring and follow-up.

Governance: Community mobilisation and inter-sectoral co-ordination supported strategies for reducing disease risk factors. Grants were allocated for promotion, prevention, early screening and rehabilitation care. Illustrative examples are the mobilisation of teens through peer-to-peer counselling within school communities for targeted purposes such as tobacco smoking and drug use (PROSTAR) and for more general behaviour change purposes such as healthier lifestyles (Doktor Muda) (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2005). New legislation established standards for care, including care of older people in private healthcare facilities, and also mandated the sale of iodised salts in districts with high risk of iodine deficiency disorders.

4.3.2.2 Integration of Preventive and Curative Services in the Public Sector

Prior to the mid-1990s, curative PHC services were provided by:

Outpatient departments (OPDs) of public sector hospitals and some satellite clinics for free or for a nominal charge.

Public sector health centres and dispensaries, also free or for a nominal charge.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, two related organisational changes within the MoH led to better integration of preventive and curative services. First, the implementation of a policy decision to move OPDs out of hospitals and into health centres began in the late 1990s and continued incrementally over the next decade. Second, this move was followed by the re-organisation of services in the health centres to better serve the goal of developing people-centred PHC.

Transfer of OPDs.

Historically, hospital OPDs primarily catered for acute episodes of illness, rarely providing health prevention or promotion, and were not geared for the continuity of care essential for non-communicable disease (NCDs). Conversely, health centres had separate arms – the family health arm had good competence for providing preventive and health promotional services for family health aimed at clients in various phases of the life cycle (pregnancy, childhood, adolescence, old age), including individuals, families and communities on a long-term basis. However, the outpatient arm of the health centres mainly provided for walk-in patients. The utilisation of OPD services evolved, with the health centres gradually overtaking the hospital OPDs in terms of volume of utilisation (Figure 4.2).

Additionally, by the late 1990s, the proportion of patients with illnesses such as hypertension and diabetes, which require long-term management, was increasing. Meanwhile, public sector hospitals had difficulties managing outpatient services (OPDs), as their focus was mainly on secondary and tertiary care. Therefore, a policy decision was implemented to transfer OPDs from hospitals to health centres.

Re-organisation of health services.

The outpatient services in health centres were re-vamped to cater to the integration of preventive and health promotional services with illness management (Economic Planning Unit, 1996). The health centres adopted a new approach that integrated basic PHC concepts in addressing the continually expanding initiatives required to deal with NCDs. Box 4.5 summarises the concepts involved, and the illustrative case study on REAP-WISE (Reviewed Approach: Wellness, Illness, Support Services, Emergency Information) elaborates on the initiative. Imaging, laboratory and pharmacy facilities were upgraded progressively as staff and physical infrastructure became available (Economic Planning Unit, 1996; 2001). Communication between primary, secondary and tertiary care was strengthened, and information systems were upgraded to include electronic personal medical records that facilitated the integration of information from the various services that catered to each patient and family (Economic Planning Unit, 2001).

The health centre services renewed the PHC concept with a new approach to accommodating its additional services, namely:

1. Preventing and reducing disease burden by treating the ill, managing those with risks and preventing the onset of preventable risks.

2. Enhancing healthcare delivery for fast access to safe and high-quality services with greater comfort in a hassle-free environment.

The wellness focus covers the life-course from antenatal to child and geriatric age for early identification of and management of medical conditions. All new activities for wellness are mapped against age group needs. Teams oversee policy development for the collective activities for each age group in order to integrate workflow processes, accounting for monitoring indicators, quantity and quality of human resources required, the diagnostic equipment, pharmaceutical requirements, and physical space for these activities. These workflow processes are then phased in at clinics nationwide.

Gaps and limitations to the integration and re-organisation.

This re-organisation process required the re-allocation of budget and human resources between hospitals and health centres, and it also required re-engineering health information systems to provide real-time access to patient information for care providers at primary and secondary level. Table 4.5 illustrates the gaps and challenges in integration and re-organisation as well as the action taken to address such challenges.

| Gaps and challenges | Action taken | |

|---|---|---|

| Finance | Limited | Transfer of OPDs was done incrementally over a period of more than a decade |

| Health workforce | Rapid turnover of staff, particularly junior doctors who needed rotational postings as part of career development |

|

| Medical products | Hospitals and health centres have separate budgets for pharmaceuticals – it was difficult to estimate the portion of hospital pharmacy budget needed for OPD as separate from inpatient care | State-level pharmacy departments took over budget management for pharmaceuticals for both health and hospital services |

| Service delivery |

|

|

4.3.2.3 Focus on Improving Quality of Care