Introduction

You should know, dear brother … that in every manual craft the matter dealt with consists of naturally occurring material, and that all its products are physical forms. The exception is music, for the ‘matter’ it deals with consists entirely of spiritual substances, namely, the souls of those who listen to it.

The Ikhwan us-Safa’ (Brethren of Purity), c. 950–1000.Footnote 1

It is impossible to capture the essence of music in pen and ink on the surface of a page.

How do we write histories of the ephemeral: of emotional and sensory experiences, of ecstatic states and aesthetic journeys, of the live performance of music and dance, of the tangible yet transient texture of the experiential moment? More to the point, how do we write such histories when those moments have long passed into silence? Can experiential moments even have histories? Surely, the momentary is the very definition of something that lies beyond history, beyond historical method. Isn’t that the essence of its bittersweet pleasures: that, once over, it forever lies beyond our reach? How far can ink and paint on the surface of a page transport us into the experience of those, long dead, who once tasted those intensities, and for whom those moments were the warp and weft of their deepest personal and collective selves?Footnote 3 Can reflections on the emotions, the senses and the performing arts tell us critical things about the harder-edged worlds of political, economic and social history that we could never otherwise access? What was the relationship between the aesthetic, the affective, the ethical, the political and the personal in South Asian history?Footnote 4 And what was at stake for North Indian men and women when their cherished musical worlds were turned upside down in the final century of upheaval that saw the Mughal empire give way to the British Raj?

In a series of six interlocking essays and a summative discussion, this book addresses these compelling but elusive questions through a focus on music, musicians and writing about them in late Mughal India (c. 1748–1858). The Mughals were a Central Asian Sunni Muslim dynasty who from 1526 ruled over large parts of the Indian subcontinent from the magnificent northern cities of Delhi and Agra, ostensibly until 1858. In reality, the Mughal empire began to disintegrate after the death of Emperor Aurangzeb cAlamgir in 1707,Footnote 5 which created a power vacuum that was filled initially by a series of resurgent regional powers, most successfully the Maratha Confederacy,Footnote 6 and ultimately by their ruthless foreign competitors the British East India Company. Through an exploration of six different types of writing on music prominent in late Mughal India, this book retells the stories of nine mostly forgotten élite musicians – five men, four women – and the courtly worlds they inhabited during the consequential final century of transition from Mughal to British rule. My time frame begins with the death in 1748 of the last Mughal emperor to retain any real geopolitical power, Muhammad Shah. It ends with the British overthrow of the last emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar in 1858, as punishment for his role as figurehead of the cataclysmic 1857 Indian Uprising, the Ghadar.Footnote 7 For those more familiar with colonial perspectives, this was the century of the East India Company’s conquest of India, from the Battle of Palashi (Plassey) in 1757 to the imposition of British Crown rule in 1858 after the Company nearly lost control of its Indian possessions entirely.Footnote 8

The geographical heartlands of this book are the vast alluvial plains and rocky hills of northern India, known as Hindustan,Footnote 9 that stretch out beneath the Himalayan foothills for over 1,200 miles watered by the rich Yamuna and Ganges river systems, though the Deccan Plateau to the south also comes into frame from time to time (see Map, p. xxi). Because of the violent collapse of the Mughal centre (c. 1739–61), which Indian writers of the time called ‘the scattering’ (Chapter 3),Footnote 10 this book’s time frame was one of unprecedented migration across India for Mughal service personnel of all kinds, including many of the court’s greatest performing artists (alongside numerous others who claimed to be). Successive chapters follow élite musicians chronologically from the Mughal imperial capital, Delhi, with its grand new city and fortress of Shahjahanabad completed in 1648,Footnote 11 to major alternative centres of cultural patronage in Lucknow, Hyderabad, Jaipur and among the British (1748–1842). We then return to Delhi and Lucknow for final chapters on the late flowering and sudden death of the Mughal imperium (1803–58), after the East India Company finally took Delhi from Maratha control in 1803.

The transition from Mughal to British rule has been of critical interest to historians of South Asia for the past forty years.Footnote 12 The dominant historiographical debate concerns the nature and extent of colonialism’s impact on the knowledge systems of the colonised, from the very fundamentals of South Asian civilisation such as caste, religion and law to language politics and artistic production. Until the mid-2000s, opposing arguments contended that British authorities either made use of pre-existing Indian knowledge systems, gradually transforming them as they gained power and territory, or, alternatively, ‘invented’ them largely ex nihilo in the Orientalist exercise of power-knowledge over those they ruled.Footnote 13 Jon Wilson has noted that proponents of both sides were in fact largely arguing past each other: those perceiving continuity and incremental change were mostly eighteenth-century historians, while those insisting on dramatic rupture and invention of tradition generally did so from the perspective of late colonialism.Footnote 14 But the central flaw in the whole debate was articulated by Sheldon Pollock in 2004. He noted that the argument was largely raging in the absence of sufficient, sometimes any, knowledge of those pre-existing Indian systems: very few of the main contenders were working from the early modern Indian sources that embody such knowledge, other than those translated into English during the colonial era.Footnote 15 This was not due to a lack of pre- or paracolonial Indian sources, either.Footnote 16 ‘South Asia’, Pollock wrote, ‘boasts a literary record far denser, in terms of sheer number of texts and centuries of unbroken multilingual literacy, than all of Greek and Latin and medieval European culture combined’.Footnote 17

Music and Musicians in Late Mughal India thus stands on Pollock’s foundational proposition, that while

the impact of colonialism on culture and power has been the dominant arena of inquiry in the past two decades … colonial studies has often been skating on the thinnest ice, given how much it depends on a knowledge of the precolonial realities that colonialism encountered, and how little such knowledge we actually possess … we cannot know how colonialism changed South Asia if we do not know what was there to be changed.Footnote 18

In the two decades since, several scholars have enthusiastically taken up Pollock’s challenge to examine ‘what was there to be changed’, notably in the fields of Mughal, Rajput and sectarian literary and cultural history during the long eighteenth century. By foregrounding South Asian visual and especially textual sources in Persian, Hindavi and other early modern languages that had mostly remained unstudied in modern times, this rich new scholarship has delivered groundbreaking insights into the wider social, economic and political dynamics of pre- and paracolonial North India.Footnote 19 Fewer scholars prioritising Mughal sources and perspectives, however, have moved past the 1750s,Footnote 20 or specifically engaged the thorny historiographical questions of how and why Pollock’s ‘precolonial realities’ changed as a result of the Mughal–British transition (c. 1748–1858).Footnote 21

Crucially, then, this book addresses both the ‘what’ and the ‘how’ parts of Pollock’s challenge. Firstly, it extends the new scholarship on pre-existing Indian knowledge systems for the first time to the field of music (including danceFootnote 22) through an extensive evaluation of Persian and to a lesser extent Brajbhasha and Urdu writings on Hindustani music and its reception between 1593 and 1869, most of which have not been examined before.Footnote 23 Secondly, by narrowing the focus to the decades of the Mughal–British political transition (1748–1858), and by placing Indian writings from this critical period into sustained dialogue with East India Company and other English-language texts, I am able to demonstrate how and why late Mughal fields of music and dance changed through this critical century of British colonisation, including via select European patronage of Indian performing arts.

Music and Musicians shows that the transitional world of late Mughal and early colonial India does look different when we prioritise the perspectives (plural) of Indian sources and triangulate them against European ones. And as we shall see, the many traces that remain on paper of the ephemeral arts of music and dance, their theory, practice and appreciation, do indeed tell us things we would not otherwise know about how very different types of people related to the arts and to each other in intense, intimate moments of both relief and tension; how those relationships and moments were experienced and understood; and what all this meant for politics, economics, society and culture in North India at this pivotal time.

The chapters in this book are thus of substantial relevance to all historians of the transition to British rule in South Asia, not simply those interested in the arts. But this time frame is also crucial to Indian music history because, as this book demonstrates, this was simultaneously the century during which the major pre-existing knowledge system known today as ‘North Indian classical’ or Hindustani music became fully established in its modern form. It is the discrete, socially élite field of Hindustani music, its performers and its audiences that is the specific focus of Music and Musicians, and thus a brief introduction to what this musical field then encompassed is essential.

The Field of Hindustani Music c. 1700

The Persian word Hindustani means ‘of or from the geographical region of Hindustan’. It is most commonly used to denote the dominant colloquial language of late Mughal India that was divided into what we now call Hindi and Urdu in the later colonial period.Footnote 24 These days, literary historians tend to use the umbrella term Hindavi for the related early modern dialects of Hindustan that include the two courtly ancestors of Hindi and Urdu, Brajbhasha and rekhta, in which many (but not all) song genres of Hindustani music were composed.Footnote 25 But the referents of ‘Hindustani music’ are more particular than simply geographical or linguistic, not least because this distinct musical system was patronised in courtly centres well beyond the borders of Hindustan proper, from Gujarat and Punjab in the west to Nepal in the north, Bengal in the east and as far south as Hyderabad, Arcot and Maratha Tanjore.Footnote 26

The term ‘Hindustani music’ to describe a circumscribed field of music-technical features, theoretical and aesthetic discourse, song and instrumental repertoires, performing communities and performance and listening practices was established at the Mughal imperial court before the mid-seventeenth century. The earliest uses I have found of the term are in the Pādishāhnāma (c. 1636–48), the official chronicle of Emperor Shah Jahan’s reign (r. 1628–58), to segregate a set of Indian song genres, key music-technical features and specialist performers from the Persian and Central Asian musical systems also patronised by the Mughals.Footnote 27 In 1663/4, the Mughal theorist Qazi Hasan further narrowed down the field to northern India specifically, distinguishing the rāga-based system of ‘the province of Hindustan’ – the subject of his treatise – from the rāga-based systems then current in the southern ‘provinces of the Deccan, Telangana and Karnataka’.Footnote 28 But Hindustani music as a recognised, delimited field long predated its labelling: by 1593 the key Mughal ideologue Abu’l Fazl had already mapped what was clearly the same field as it was practised at the North Indian court of Emperor Akbar I (r. 1556–1605) – but instead called it by the proper Sanskrit term for rāga-based music and its connected arts, saṅgīta.Footnote 29

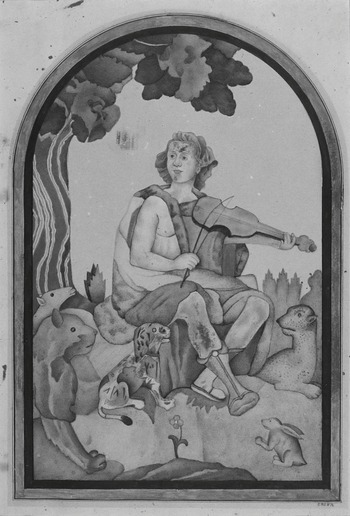

As the term rāga-based indicates,Footnote 30 the core defining feature of Hindustani music, then as now, is the primacy placed on rāga as its fundamental melodic framework. Rāga refers to the unique South Asian system of highly aestheticised melodic modes that have been theoretically systematised in written treatises and performance practice for more than a millennium.Footnote 31 The Hindustani and Karnatak (South Indian) rāga systems began to diverge in their aesthetic conception around 1550.Footnote 32 For those unfamiliar with South Asian music, a rāga is not the same kind of entity as a European scale or mode, nor is it a fixed melody. In the Hindustani system, as David Lunn and I have explained, each rāga exists ‘in both a sonic form, and an iconic form. … In their sonic form, ragas are melodic formulae – ascending and descending note patterns with special additional rules – that act as blueprints for composition [and improvisation], and produce a unique character or soundmark for each raga. The soundmark produced by specific melodic gestures in each raga is associated with a distinct emotional flavour … and with a particular time of day or season of the year. Sung correctly, every raga is supposed to have a specific effect on the listener’s physical or psychological well-being or on the wider natural world. … In the ragas’ iconic forms, these associations are assembled into painted icons and poetic imagery. Since the fourteenth century, Indian poets and musicologists have described the ragas as beautiful heroines, brave heroes, sages, joginis and gods. … And since the sixteenth century, the ragas have been painted in suites of six male ragas, each with five wives called raginis and known as a “garland of ragas” – the ragamala’ (e.g. Figures 2.2, 5.4).Footnote 33 By the late seventeenth century, music theorists had reached a consensus on the pre-eminence of one principal rāgamālā system (mat) in Hindustani music, the Hanuman mat (Table 7.1).

In other words, before the Mughals even arrived in India, the rāgas were already richly aestheticised objects of erudite connoisseurship associated with India’s courtly arts and literature. The primacy of rāga to Hindustani music thus further marked this field out, explicitly, as élite – as the exclusive provenance of the courtly and literate social classes who together ran the institutions of government and civil society in late medieval and early modern North India. Indeed, as it metamorphosed over previous centuries, the whole field of rāga-based music had been repeatedly subject to deliberate processes of canonisation, standardisation and systematisation in writing – what I have called ‘classicisation’ processesFootnote 34 – most recently in the fifteenth century under the Rajput rulers of Mewar and Gwalior and the sultans of Jaunpur and Delhi.Footnote 35 But it was under the Mughals, between the reigns of Akbar I (r. 1556–1605) and Akbar II (r. 1806–37), that the full constellation of élite discourse, practices, performers and modes of listening that became known as ‘classical’ in the twentieth century was consolidated and codified.Footnote 36

Thanks to the pioneering research of Shahab Sarmadee, Françoise ‘Nalini’ Delvoye, Najma Perveen Ahmad, Madhu Trivedi and Prem Lata Sharma, it is now well established that in the seventeenth century, authors associated with the Mughal court started producing a plethora of new systematic writings on the rāga-based music of Hindustan.Footnote 37 As I discuss in Chapter 2, they translated older, especially Sanskrit, treatises and oral lore into the two new Mughal languages of courtly power and literature, Brajbhasha and Persian, intermingling the old with new material to remake élite musical discourse for a culturally mixed courtly regime that actively delighted in difference. From the sixteenth century onwards both the Mughals and their courtly Hindu counterparts the Rajputs prized a virtuosic aesthetic of borrowing and reuse from the Indic to the Persianate realms and vice versa. Artists and writers adopted ideas, literary topoi, visual and sonic symbols and complex imagery from one realm, and repurposed them across religions, languages, media and genres. This led over time to multiple depths and tangents of meaning speaking simultaneously in any one work of art or literature.Footnote 38 The new wave of seventeenth-century Mughal writings on music were steeped in this aesthetic. Their authors translated, mixed and remade written musical discourse afresh in order to ‘reclassicise’ Hindustani music for the ascendant Mughal dispensation with its cognate central ideology of sulh-i kull, ‘universal civility’, in which the emperor’s role was to unify India’s considerable religious, social and cultural diversity under his unitary harmonious benevolence.Footnote 39 But in making rāga-based music theirs by writing knowledgeably about it, Mughal courtiers also marked themselves out as true members of India’s élite classes, firmly set apart from the uneducated masses who did not listen to rāga, and nouveau riche upstarts who didn’t properly know how to.Footnote 40

By the end of Aurangzeb’s reign (r. 1658–1707), then, Hindustani music was a long-established rāga-based art music identified culturally with the courts of northern India, Hindu and Muslim, but now overwhelmingly connected with Mughal imperial and provincial, especially Rajput, patronage. With the rāgas at its aesthetic heart, the Hindustani musical field encompassed, firstly, a flourishing corpus of music-technical and philosophical writings in Sanskrit, Brajbhasha and Persian (saṅgīta-shāstra; cilm-i mūsīqī); and secondly, a performance repertoire of virtuosic song genres and instrumental forms that used rāga and tāla (the metrical cycles of the rhythmic system) as the basis of short fixed compositions and extended live improvisations. These song genres, all still in the repertoire, were composed in courtly registers of North Indian languages including Persian,Footnote 41 notably dhrupad, hoṛī, khayāl, ṭappa, tarānā and ghazal; and the main instruments were the stringed bīn (rudra vīṇā), rabāb, sārangī and Persian tambūr, and the drums pakhāwaj, ḍholak and daf/dā’ira (see Glossary).Footnote 42 Thirdly, as is still the case today, except on grand occasions these forms were performed as chamber music by small professional ensembles comprised of one or two singers and accompanying instrumentalists; slightly larger troupes of women and transfeminineFootnote 43 performers also danced. By the early seventeenth century, these forms and their performance practices were the exclusive intellectual property of multigenerational hereditary guilds built around households of male professional musicians from the endogamous kalāwant, qawwāl and ḍhāḍhī communities, and the highest-status female courtesan communities (Chapters 4, 5 and 6).Footnote 44 The great master-teachers in the male lineages, responsible for preserving and transmitting these forms, practices and their theory and aesthetics to future generations, were called ustāds.

Finally, this select repertoire was performed for discrete same-sex groups of élite friends in intimate (or semi-intimate) gatherings dedicated to the connoisseurship of the arts of pleasure called the majlis or mehfil (‘assembly’); this book largely deals with men’s assemblies.Footnote 45 Mehfil is the pervasive term today for the modern private gathering of musicians and expert listeners that is directly descended in form and etiquette from the late Mughal majlis. But like their Ottoman and Safavid counterparts, Mughal writers most often used majlis (pl. majālis) for this highly scripted élite socio-cultural institution practised throughout the Persianate world,Footnote 46 whose specific Mughal boundaries, values, transgressions and delights were so widely recorded in painting, poetry and the biographical writings called tazkiras we will spend time with in Chapters 2 and 3.Footnote 47 As we shall see, what took place in the late Mughal majlis, and what we can make of it from the faded, fragmented testimony of its long-dead participants, is key to answering the questions I posed in my opening paragraph.Footnote 48

Writing on Music in the Late Mughal World

Eagle-eyed aficionados of Hindustani music will already have noted key absences in my outline of the field above. This is because several crucial developments in Hindustani music towards its modern state happened during the time frame of this book – the arrival of the now-ubiquitous tabla and sitār in the 1730–40s and the sarod a century later;Footnote 49 the rise of ṭappa and ṭhumrī under the Nawabs of Lucknow c. 1780–1850;Footnote 50 and wholesale shifts that we know took place in the technical conceptualisation of both rāga and tāla, from aesthetic to melodic classification and from additive to divisive cycle measurement respectively (Chapters 4, 5 and 7). The period 1748–1858 was one of the most significant eras of change for Hindustani music, in which new musical concepts, genres, instruments, performers and patrons asserted themselves on a fiercely competitive pan-Indian stage. Yet despite some vital earlier work on music-technical developments, most importantly Allyn Miner’s Sitar and Sarod in 18th and 19th Centuries,Footnote 51 what happened to Hindustani music and musicians during this pivotal transition has never been properly mapped.

This significant lacuna exists for a curious historiographical reason: a pervasive belief that the guilds of hereditary musicians now called gharānās (‘house’ like ‘house of Dior’) who exclusively possessed and passed on Hindustani music from the Mughal period down to the modern age were ‘illiterate’.Footnote 52 Historians and music scholars have long highlighted the two-thousand-year-old tradition of writing saṅgīta-shāstras in Sanskrit. But for reasons that are still obscure, Sanskrit ceased to be a significant medium for new works of music theory in North India (though not elsewhere) from c. 1700 until it was revived in the late nineteenth century as the ‘authoritative’ language of Hindustani musicology by nationalist reformers, led by upper-class Western-educated Brahmins Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande and Sourindro Mohun Tagore.Footnote 53 In the intervening years, so Bhatkhande asserted in his famous address to the First All India Music Conference in 1916, the hereditary ustāds’ alleged ignorance of written theory – ‘the real backbone of practice’ – caused Hindustani music ‘to drift away and run into disorder and confusion’, and writing on music itself to cease. ‘Our old Sanskrit Granthas’, he averred, ‘having thus become inapplicable to the current practice, we naturally have come to be thrown on the mercy of our illiterate, ignorant, and narrow-minded professionals’.Footnote 54

Modern scholarship has been considerably kinder than Bhatkhande towards North India’s hereditary professional musicians and particularly to non-written modes of transmitting traditional knowledge. Both South Asian and foreign musicologists have come to understand that while oral, aural and kinaesthetic systems of knowledge transmission from master to disciple may be configured differently to written systems, they demonstrate equivalent levels of discursive sophistication, cognitive complexity and long-term reliability.Footnote 55 But instead of treating what was so obviously an ideological topos with suspicion, modern scholars have overwhelmingly accepted as fact the basic thrust of Bhatkhande’s assertion – that the hereditary musicians could not read or write, or if the occasional ustād did possess a measure of functional literacy, they did not use it in teaching, performing or musical discourse. This is despite Ashok Ranade’s authoritative but overlooked evidence to the contrary, that hereditary musicians frequently used writing as an essential supplement to embodiment and memory.Footnote 56 Our widespread assumption of musicians’ illiteracy (or a-literacy) in the late Mughal and colonial periods has sustained an entrenched belief that there were few, if any, writings on Hindustani music between c. 1700 and the post-1857 development of printed publications in modern Urdu, Hindi and Bengali.Footnote 57 The long-standing consensus that the late Mughal was a ‘silent’ period has thus left a substantial hole in our understanding of Hindustani music’s history that has been patched only partially with the oral histories, older repertoire and remembered genealogies of modern musicians.

If this book does nothing else, it demonstrates unequivocally that this consensus is not true. Music and Musicians showcases and evaluates a vast, rich corpus of writings on Hindustani music c. 1660–1860 that has mostly been overlooked to date. In a recent European Research Council project, we documented an enormous number of writings on Hindustani music for the late Mughal period in multiple North Indian languages, as well as visual records.Footnote 58 What is more, several of the most important and original late Mughal works turn out to have been written by the very hereditary musicians written off as ‘illiterate’. Most of these writings on music have languished in the archive unnoticed, and the handful that are almost accidentally known to posterity have been misunderstood and very underutilised.Footnote 59

This book explores the contents of these writings in depth to track how and why the field of Hindustani music changed over time. But in focussing on a different genre of writing on music in each chapter, I also foreground how to read such writings in the context of broader generic considerations and of wider historical events. For alongside fresh music-technical treatises in the canonical mould, several new genres of writing on Hindustani music arose during the period 1748–1858 whose advent in the field, not merely their content, demands explanation. Among élite Indian audiences, and those Europeans who for a time aspired to be like them,Footnote 60 this proliferation of Indian-language genres included tazkiras and genealogies, song collections, innovative musical notations, rāgamālā paintings and poetry, copies of old and the creation of new musical treatises, bureaucratic records and ethnographic writings and paintings.

Many of these late Mughal writings coincided in close proximity with colonial cultural interest and/or territorial encroachment. To help us understand late Mughal authors’ varied and often surprising relationships with colonial presence without downplaying North Indian writers’ considerable agency, I make gentle use throughout this book of a novel theoretical concept: the ‘paracolonial’. This concept was first articulated by Stephanie Newell in her work on West African literary communities, and denotes ‘alongside’ and ‘beyond’ the colonial.Footnote 61 Paracoloniality has become increasingly key to our understanding of South and Southeast Asian written, visual and auditory sources during the time frame conventionally marked off as the ‘colonial period’.Footnote 62 In relation to the performing arts, we have theorised the paracolonial to refer to systems of musical knowledge and practice – Hindustani music being a principal example – that operated alongside and beyond the British colonial state. These knowledge systems were often facilitated by colonial infrastructures and technologies, and constrained by colonial law and violence. But they were not necessarily, or indeed even often, in thrall to colonial systems of knowledge. Rather, they coexisted in many differing relations and tensions with colonial thought and action on music, ‘noise’ and their proper place in society.Footnote 63

Listening to writings on music during the Mughal–British transition through the filter of the paracolonial opens up revolutionary historical soundscapes, and allows for the autonomous agency of a plurality of Indian voices within the conditions of possibility afforded to them during this time frame. But to understand these conditions, we must deal not just with the views of the Mughal and princely states, but with colonial perspectives on Hindustani music. While I prioritise Indian and mixed-race (Eurasian) voices in this book, the period c. 1770–1840 was also when leading British interest in the Indian arts was at its peak. Many European colonisers in this century collected and even commissioned Indian musical manuscripts and paintings; and their marginalia, private papers, musical transcriptions and treatises, published travels and the official records of the East India Company illuminate shadowy corners that the more brilliant lights of the Indian materials don’t always reach. When these rich and diverse Indian and European writings are read in context and, crucially, in conversation with each other, this extraordinary written and visual archive dramatically changes what is possible to write about the history of music, musicians and their audiences in late Mughal and early colonial India.

Chasing Eurydice

But this book is not just concerned with the content and historical emergence – the ‘what’ and ‘how’ – of these writings on Hindustani music. My deeper interest lies in the act of writing on music in late Mughal India. Music and Musicians seeks to answer the question why all these Indian, mixed-race and English intellectuals and musicians chose to write about Hindustani music so copiously in this particular century, when all of them believed – as Sher cAli Khan Lodi put it so eloquently in 1691 – that the task was impossible. Before the advent of the sound recording, once music stops sounding all we are left with is what Persian writers called the scratchings of a ‘broken pen’, a common idiom expressing authorial inadequacy,Footnote 64 but one that I will take seriously in this book. What were writers on music in the late Mughal and early colonial world trying so desperately to hold onto? Why? And what can we learn from their attempts?

The underlying quest of this book takes its inspiration from the figure of Orpheus inlaid in pietra dura in solitary splendour above the throne in Shahjahanabad’s Exalted Fortress (Qilca-i Mucalla) at the heart of the Mughal imperial city of Delhi (Figure 1.1) – a figure with whom the Mughal emperor personally identified as a sonic symbol of his divinely ordained power (Chapter 2). My fundamental philosophical question is this: if writers are akin to Orpheus, and if Eurydice is the music of late Mughal Hindustan in all its fullness – all its sensory, emotional, intellectual, ethical, social and political manifestations – is it ever possible for Orpheus to bring Eurydice back from the dead? To what extent, in other words, were writers on Hindustani music at the time able to pin music’s experiences and meanings down on the page; and to what extent, centuries later, can we use what they wrote to understand what Mughal listeners heard and felt then, when we can no longer hear a single note of the music they were so desperately trying to capture on paper with broken pens?

Figure 1.1 Painting of the pietra dura inlay of the figure of Orpheus behind the throne in the Hall of Public Audience, Shahjahanabad. Delhi, 1845. 292D-1871.

The ultimate answer is no. For music is fundamentally an impossible object of historical enquiry. Music is only ever fully realised in the living moments of our experience of it; once its sounds have died away, those moments cannot be recaptured. In theory, the music-technical treatises I deal with in this book, especially those written by the hereditary Mughal ustāds who sang Hindustani music into being, should give us privileged access to its sounds. And indeed, as always, the devil does lie in the detail; there are whole worlds in these manuscripts that I am unable to explore here. But in my decades’ experience of working with Mughal treatises, when it comes to the essence of what they truly believed music to be – ‘the arousal of tender sympathy in the heart’Footnote 65 – Mughal music-technical writing can be as dry and unyielding as old bones.Footnote 66

More than a thousand years ago, the Sufi Brethren of Purity knew that the matter of music did not lie in such things, in any case, but in the souls of those who listen to it. The performers and listeners whose souls once delighted in the refined emotions and sensory experiences of the late Mughal majlis, too, have long turned to clay. And yet, we still have their writings. Theirs are the very same voices that echo back to us through the pages of our extraordinary primary sources. And they did not just write technically; they wrote other things, in other places, other voices and other genres that enable us to breathe back into those skeletal remains some vestige of the spirit that once enlivened them. This is why I have chosen to focus, not so much on the ‘music itself’ in this book, as on the life stories of musicians and those who loved them. Because it is the collective experiences of all those human souls, living through an era of terrible disquiet, that are the true substance of Hindustani music in late Mughal India.

Writing on music can never bring Eurydice back. But Music and Musicians shows that it is the journey into the underworld of the written archive itself, where her many echoes still resound, that tells us more about those lived musical worlds than we ever imagined. Music in late Mughal India existed to move the emotions of men and women in collective experiences; music was a whirl of sound and emotional response and search for meaning. In the writings of long-dead musicians and their élite patrons, we hold in our hands the earwitness testimonies of historical listeners. Although we have lost the sounds of late Mughal India, their writings – their own histories of the ephemeral – not only give us qualified access to what music meant and felt like then to all those who loved it, but may also enable us to sense those things too.