INTRODUCTION

The COVID pandemic has shaken the global environment around the world. For instance, in 2020, foreign direct investment or FDI decreased by 42% from the previous year (UNCTAD, 2018). In this article, we examine how this exogenous worldwide COVID shock, as well as the social and public policies to contain the pandemic, have affected business confidence. The Business Confidence Index (BCI) captures business people's expectations about the near future (in relation to future production, order book levels, and stocks of finished goods). Also, it provides a dynamic view of the economy and it is a good indicator to anticipate changes in the business cycle (Dasgupta & Lahiri, Reference Dasgupta and Lahiri1993; Ha, Reference Ha2020; Hansson, Jansson, & Löf, Reference Hansson, Jansson and Löf2005; Khan & Upadhayaya, Reference Khan and Upadhayaya2020; Lehmann, Reference Lehmann2020; Taylor & McNabb, Reference Taylor and McNabb2007; Vanhaelen, Dresse, & DeMulder, Reference Vanhaelen, Dresse and DeMulder2000). Therefore, investigating the effects of the COVID shock on business confidence enables us to shed some light on how corporations are likely to behave in regards to their future investments and business management decisions (including financial choices).

Previous studies have analyzed the relationship between business confidence and several key economic variables, such as fiscal and monetary policy or economic stability (Alesina, Favero, & Giavazzi, Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2015; Beetsma, Cimadomo, Fortuna, & Giuliodori, 2015; Dajčman, Reference Dajčman2020; Konstantinou & Tagkalakis, Reference Konstantinou and Tagkalakis2011; Leduc & Sill, Reference Leduc and Sill2013; Lewis, Makridis, & Mertens, Reference Lewis, Makridis and Mertens2019; Pranesh, Balasubramanian, & Mohan, Reference Pranesh, Balasubramanian and Mohan2017). By the same token, there is growing literature studying the effects of the COVID pandemic on the economy, financial markets, households’ and business confidence (Ambrocio, Reference Ambrocio2021; Baek, McCrory, Messer, & Mui, Reference Baek, McCrory, Messer and Mui2020; Buckman, Shapiro, Sudhof, & Wilson, Reference Buckman, Shapiro, Sudhof and Wilson2020; Chen, Igan, Pierri, & Presbitero, Reference Chen, Igan, Pierri and Presbitero2020; Chronopoulos, Lukas, & Wilson, Reference Chronopoulos, Lukas and Wilson2020; Deb, Furceri, Ostry, & Tawk, Reference Deb, Furceri, Ostry and Tawk2020; Fetzer, Hensel, Hermle, & Roth, Reference Fetzer, Hensel, Hermle and Roth2020; Goolsbee & Syverson, Reference Goolsbee and Syverson2021; Kanapickiene, Teresiene, Budriene, Keliuotytė-Staniulėnienė, & Kartasova, Reference Kanapickiene, Teresiene, Budriene, Keliuotytė-Staniulėnienė and Kartasova2020; Kok, Reference Kok2020; König & Winkler, Reference König and Winkler2020, Reference König and Winkler2021; Lee, Reference Lee2020; van der Wielen & Barrios, Reference van der Wielen and Barrios2020; Vasiljeva et al., Reference Vasiljeva, Neskorodieva, Ponkratov, Kuznetsov, Ivlev, Ivleva and Zekiy2020; Verma, Dukma, Bhardwaj, Ashok, Kestwal, & Kumar, Reference Verma, Dumka, Bhardwaj, Ashok, Kestwal and Kumar2021). Yet, most of this expanding literature on COVID has focused on advanced economies or China. In contrast, in this research, we take a global perspective to study the connection between business confidence and the COVID pandemic. Importantly, we pay attention to some key aspects that have not been properly examined in the literature before: On the one hand, we investigate the effects of containment measures on business confidence distinguishing between emerging and advanced economies. On the other hand, we study the spillover effects produced by the containment measures taken by neighboring countries. To our best knowledge, this is the first global study that investigates the direct as well as the spillover effects of COVID shock on BCI.

Our main research question is the following: How has COVID shock affected business confidence in different latitudes of the globe? From this question, we open several hypotheses. First, we investigate the impact on business confidence of the various kinds of (compulsory and voluntary) policies that governments and citizens have applied to contain the COVID pandemic. Importantly, we also account for possible dynamic changes in the intensity of these policies across time. The reaction of governments to this pandemic has varied significantly. Some countries like the United States, Brazil, and Sweden have not implemented quarantine measures and mobility restrictions (to goods and to people). In contrast, some other countries like Italy, France, Argentina, and China took compulsory containment policies to control the spread of the disease.

On the one hand, investors and business people could view containment measures as positive, as these measures help mitigate the spread of the COVID disease in the medium and long term. These measures may hence create a more auspicious future perspective for businesses and encourage investors to undertake expanding business strategies. On the other hand, the economic impact in the short term is presumably negative as the containment measures imply a sharp reduction of economic activity (Deb et al., Reference Deb, Furceri, Ostry and Tawk2020). Given the opposing directions that containment measures might have (in the short versus the medium term), it is an empirical question to determine which of these two competing forces affecting BCI prevail. Furthermore, in this article, we do not aim at explaining the reasons behind each country's decision to apply stricter or more lenient policies nor which policy is better.Footnote [1] Our objective is to assess the overall effect on business confidence of the voluntary and the compulsory containment measures.

The second main aspect that we study is the different reactions to the COVID shock of business people in emerging economies compared to advanced economies. Precisely, we focus on two main dimensions: (1) whether the severity of the containment measures has been stronger in emerging or in advanced economies and (2) whether these measures have had a differential impact on business expectations in emerging economies, relative to advanced ones. Regarding the first dimension (namely, the severity of the containment measures in emerging economies compared to advanced economies), the reasons behind each country's approach to the management of the COVID pandemic can be quite diverse. The ideological standpoint of each country may be one key factor. The political orientation of the party in power and/or the political regime may become additional important variables. The cultural values that each society has regarding individual freedom versus collective responsibility can also be a decisive point. As shown by Adler et al. (Reference Adler, Sackmann, Arieli, Akter, Barmeyer, Barzantny and & Zhang2022), even the cultural influence of leaders could be a variable to consider.Footnote [2] However, there is considerable heterogeneity among countries belonging to the emerging- and advanced-economy categories, which prevents us from making clear predictions regarding the influence of these ideological, cultural, and political features characterizing the countries. From an economic standpoint, the larger material capabilities and resources that advanced economies have, in comparison with emerging ones, may be an additional distinctive factor: advanced economies may have larger technological, research, and development capabilities (for example, to develop the vaccine), better infrastructure, better health care systems, and more developed social programs to contain the effects of such an exogenous shock. According to this view, one would expect that emerging economies might have needed to (or might have had incentives to) implement stricter containment measures to mitigate the COVID shock, relative to advanced economies, to compensate for the fewer material resources and capabilities (to develop vaccines and build hospitals, for example).

On the other extreme, there are also reasons to expect that emerging economies would avoid implementing strict containment measures. To begin with, implementing strict containment measures presumably results in smaller tax collection (due to the lower economic activity), thus further damaging the fiscal positions of these countries (emerging economies usually have weaker fiscal balances). A second factor that could discourage emerging economies from applying strict containment measures is related to their institutional characteristics. Implementing strict containment measures implies the need to control the application of these policies; it also requires a large group of qualified bureaucrats to design these measures and to enforce them. Third, some emerging economies’ past experiences to deal with previous pandemics, such as Cholera, SARS, or Ebola (mainly in Southeast Asia and West Africa), may have provided them with experience to deal with the COVID pandemic, thus allowing them to avoid applying strict containment measures. Fourth, there are some emerging economies that have had the ability and resources to implement effective social health care and vaccine programs (e.g., Chile). Nevertheless, in comparison to advanced economies, emerging economies tend to have, on average, weaker institutions (Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson, & Thaicharoen, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson and Thaicharoen2003; Brinks, Levitsky, & Murillo, Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2019) and bureaucracies (Rauch & Evans, Reference Rauch and Evans2000), and poor enforcement controls (Spiller & Tommasi, Reference Spiller and Tommasi2008). Hence, when these countries assess the feasibility of executing strict containment measures, they could realize that – even if they want to – they might be unable to implement these strict containment measures due to the fewer resources and capabilities they have. As a result, they may reject this option. Summing up, determining which of these opposing forces prevail (resulting in stricter or more lenient containment measures) is an empirical question that we will address in this paper.

Concerning the second dimension in the emerging/advanced economies’ analysis (that is, whether the containment measures have had a larger impact on business expectations in emerging economies relative to advanced ones), one could argue that business people operating in emerging economies are typically more used to a greater level of instability, uncertainty, and drastic public policy changes (Aguilera, Ciravegna, Cuervo-Cazurra, & Gonzalez-Perez, Reference Aguilera, Ciravegna, Cuervo-Cazurra and Gonzalez-Perez2017; Finchelstein, Reference Finchelstein2017; Friel, Reference Friel2021; Garcia-Sanchez, Mesquita, & Vassolo, Reference Garcia-Sanchez, Mesquita and Vassolo2014). As a result, corporations in these economies may learn to have more flexibility and adaptability skills to handle instability and uncertainty, and therefore, they may be better prepared to deal with such a large negative shock. If this is the case, then the containment measures taken in emerging economies should have a smaller impact on business confidence relative to the effect of the containment measures taken in advanced economies. We will determine whether this hypothesis is consistent with the data or not.

The third important aspect that we study refers to the spillover (or indirect) effects of compulsory containment measures taken by ‘neighboring’ countries.Footnote [3] We rely on Ghemawat (Reference Ghemawat2001, September)'s framework of distances to conceptualize the identification of neighboring countries. This conceptualization implies considering the geographic and cultural ties between countries, as well as their economic and administrative linkages (Ghemawat, Reference Ghemawat2001, September). Studying these spillover effects is important because they enlighten us on whether business people are reluctant to the overall idea of more compulsory containment measures beyond the ones that are specifically directed to them. One possible interpretation of the spillover effects is that business people may become less confident about the future when the containment measures are implemented in their own countries, as they have to pay the costs of these measures (the negative impact on economic activity), but they cannot fully appropriate the total world benefits (which are larger than the benefits to the country implementing the measure). In contrast, when the containment measures are taken elsewhere, business people can profit from the total world benefits of these measures, without paying the costs; they may hence become more confident about the future when containment measures are implemented elsewehere.

Through a quantitative analysis of 43 emerging and advanced economies (12 of which are emerging economies), we quantify the impact of the COVID pandemic shock on business confidence. We rely on a panel data estimation over the period January 2018–December 2020, with monthly frequency. For the empirical analysis, we also control for standard country-specific macroeconomic factors (as the monetary and fiscal policy), global factors, and political, institutional, and economic features characterizing the various countries in our sample. Given the nature of this quantitative study, we cannot fully account for the multiplicity of factors characterizing each country. Nevertheless, our research allows us to identify some interesting patterns regarding the effects of the COVID pandemic on business expectations and investments by exploiting the differences between advanced and emerging markets and by distinguishing between the direct and spillover effects.

Our research provides a diverse set of contributions. First, it contributes to the study of the impact of the exogenous COVID pandemic on corporations (Baek et al., Reference Baek, McCrory, Messer and Mui2020; Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke, & Zimmermann, Reference Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke and Zimmermann2020; Chakravorti, Bhalla, & Chaturvedi, Reference Chakravorti, Bhalla and Chaturvedi2020; Fetzer et al., Reference Fetzer, Hensel, Hermle and Roth2020; Hasija, Padmanabhan, & Rampal, Reference Hasija, Padmanabhan and Rampal2020, June 1; Kanapickiene et al., Reference Kanapickiene, Teresiene, Budriene, Keliuotytė-Staniulėnienė and Kartasova2020; Schor, Reference Schor2020; van der Wielen & Barrios, Reference van der Wielen and Barrios2020). These effects could be analyzed from a micro/industrial perspective (focusing, for example, on the various organizational and strategic approaches) but also from a broader macro perspective. Our study relates to the second sub-group of studies. In particular, this macro empirical literature tends to show that COVID shock and the crisis-induced constraints drastically affected economic activity, performance of financial markets, households’ economic sentiment, and business confidence. However, the majority of the studies mainly focus on one or a few countries or regions, namely, the United States, Europe, and some studies also on China. We contribute to this literature by being the first to study both the direct and spillover effects of COVID shock on business confidence, relying on a global sample of advanced and emerging economies over a recent period of time.

Second, this study contributes to the field of development economics, as we assess the differential effect that the COVID pandemic has had on emerging economies with respect to advanced ones (Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2002; Addison, Sen, & Tarp, Reference Addison, Sen and Tarp2020; Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2005; Dingel & Neiman, Reference Dingel and Neiman2020; Kok, Reference Kok2020; König & Winkler, Reference König and Winkler2020; Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000, Reference Mahoney2010; Maloney & Taskin, Reference Maloney and Taskin2020).Footnote [4] To our knowledge, there is no previous research studying the heterogeneous reactions of business confidence distinguishing between these two groups of economies. Most importantly, our findings can help to have a better understanding of how business confidence varies differently depending on the developmental stage of each country.

Third, our study could also be complementary to research on the impact of recessions in firms’ competitive advantages (Latham & Braun, Reference Latham and Braun2011; Mascarenhas & Aaker, Reference Mascarenhas and Aaker1989; Vassolo, Garcia-Sanchez, & Mesquita,, Reference Vassolo, Garcia-Sanchez and Mesquita2017). In these studies, preferential access to resources has been studied to predict which firms are more likely to perform better during a recession. The pandemic has resulted in a significant and widespread economic recession. Our comparison between emerging and advanced economics, which have differential access to material resources, hence provides some useful conceptual and empirical insights that contribute to this area of study.

Finally, we contribute to the area of institutionalism, a phenomenon that has been studied by several disciplines, such as economics (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson and Thaicharoen2003; North, Reference North1990), political science (Hall & Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001; Schneider, Reference Schneider2013; Thelen, Reference Thelen2004), and management (Finchelstein, Reference Finchelstein2017; Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu2006; Kumar, Mudambi, & Gray, Reference Kumar, Mudambi and Gray2013). We add to this literature by exploring whether and to what extent stronger institutions and greater resources have allowed countries to apply lighter compulsory containment measures. This reinforces the idea that institutional settings shape the behavior of all political actors (including businesses, Hall & Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001). We also offer some interesting findings for the international relations and international business sub-fields, as we investigate whether stronger political decisions to contain COVID in neighboring countries have any effect on business confidence. Ultimately, the heterogeneity of states’ responses to the COVID pandemic, mediated by the just-described institutional differences, may explain the variability found in the business confidence index (BCI) across the globe.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

The COVID pandemic has shaken global business: from industries that have seen their sources of revenue dramatically shrunk to the emergence of new ways of doing business (Caligiuri et al., Reference Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke and Zimmermann2020; Chakravorti et al., Reference Chakravorti, Bhalla and Chaturvedi2020; Hasija et al., Reference Hasija, Padmanabhan and Rampal2020, June 1; McKinsey, 2020). The effect of the pandemic on corporations is being studied from a wide variety of perspectives. For instance, some studies have focused on the effects in some particular industries (Gavet, Reference Gavet2020, September 30), some other works explore new challenges for firms given the geopolitical reorientation and new position of several states with respect to the free movement of people (Ankel, Reference Ankel2020; Chakravorti et al., Reference Chakravorti, Bhalla and Chaturvedi2020; Contractor, Reference Contractor2020), while others have examined how corporations have adapted their organizational and management strategies to this new context (McKinsey, 2020; Tognini, Reference Tognini2020). In addition, some researchers are investigating how the COVID shock has affected labor relations, the use of new forms of communication and working tools, as well as the emergence of new types of jobs such as gig works (Dingel & Neiman, Reference Dingel and Neiman2020; Hasija et al., Reference Hasija, Padmanabhan and Rampal2020; Schor, Reference Schor2020).

In this article, we contribute to the study of this phenomenon by examining how the exogenous COVID shock as well as the social and public policies to contain the pandemic have affected business confidence. The BCI captures investors’ expectations about the near future. Therefore, it is strongly related to corporations’ investments and business management decisions. Also, the BCI provides a dynamic view of the economy (relative to FDI which shows a more static picture in a particular moment of time). By exploring the effects of COVID shock and the social and public policies to contain the pandemic on business confidence, we hence aim at offering a good measure of the impact of the COVID shock on corporations’ activity and business cycle. As a matter of fact, business confidence has been vastly reviewed in relation to its effects on economic stability (Leduc & Sill, Reference Leduc and Sill2013; Pranesh et al., Reference Pranesh, Balasubramanian and Mohan2017), and its link to fiscal and monetary policy (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2015; Beetsma et al., Reference Beetsma, Cimadomo, Furtuna and Giuliodori2015; Dajčman, Reference Dajčman2020; Konstantinou & Tagkalakis, Reference Konstantinou and Tagkalakis2011; Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Makridis and Mertens2019; among others). As an illustration of the latter, recent evidence about the effect of the current global COVID shock on FDI suggests that the economic downturn created by the pandemic has – at least monetarily – decreased the disposition of investors to provide more capital into global markets (UNCTAD, 2018).

From a macro perspective, there is a vast literature on how and why corporations make their investment decisions (Asiedu, Reference Asiedu2002; Globerman & Shapiro, Reference Globerman and Shapiro2003; Henisz, Reference Henisz2000). Some scholars put emphasis on the institutional voids that define the modes of entry and the ways of organizing businesses (Doh, Rodrigues, Saka-Helmhout, & Makhija, Reference Doh, Rodrigues, Saka-Helmhout and Makhija2017; Henisz & Williamson, Reference Henisz and Williamson1999; Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu2006; Stal & Cuervo-Cazurra, Reference Stal and Cuervo-Cazurra2011), whereas some other scholars have studied how exogenous shocks have an impact on investment and business activity. The most common of these exogenous shocks are terrorism (Barth, Li, McCarthy, Phumiwasana, & Yago, Reference Barth, Li, McCarthy, Phumiwasana and Yago2006; Duque, Andonova, & Correa, Reference Duque, Andonova and Correa2021; Oetzel & Oh, Reference Oetzel and Oh2014), domestic or international political conflicts and wars (Barbieri & Levy, Reference Barbieri and Levy1999; Henisz, Reference Henisz2000), and environmental crises and natural catastrophes (Chung, Reference Chung2014; Mithani, Reference Mithani2017; Yoon & Heshmati, Reference Yoon and Heshmati2017). Most of these exogenous shocks bring challenges to businesses, such as trade contraction, supply chain interruption, and the overall increase in transaction costs (Aggarwal, Reference Aggarwal2006; Blomberg & Hess, Reference Blomberg and Hess2006; Czinkota, Knight, Liesch, & Steen, Reference Czinkota, Knight, Liesch and Steen2010; Henisz, Mansfield, & Von Glinow, Reference Henisz, Mansfield and Von Glinow2010; Mithani, Reference Mithani2017). In relation to investments, there are several studies documenting that investments tend to decline following a negative exogenous shock of the type mentioned above (Bandyopadhyay, Sandler, & Younas, Reference Bandyopadhyay, Sandler and Younas2014; Lutz & Lutz, Reference Lutz and Lutz2006; Polyxeni Theodore, Reference Polyxeni and Theodore2019). However, due to the nature of these shocks (which were typically local or regional), most of the prior literature studying them has focused on a reduced number of regions or countries.

In contrast, the COVID shock has shaken the world, affecting all countries. It hence requires a global perspective when studying its impact. On top of that, compared to previous pandemics (e.g., the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic and the HIV/AIDS pandemic), the world is now more connected, with better communication and greater trade; also, new data is available to develop significant and novel analyses. The empirical macro literature studying the economic consequences of the COVID pandemic continues to grow (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Sackmann, Arieli, Akter, Barmeyer, Barzantny and & Zhang2022; Ambrocio, Reference Ambrocio2021; Andersen, Hansen, Johannesen, & Sheridan, Reference Andersen, Hansen, Johannesen and Sheridan2020; Baek et al., Reference Baek, McCrory, Messer and Mui2020; Baker, Bloom, Davis, & Terry, Reference Baker, Bloom, Davis and Terry2020; Barro, Ursúa, & Weng, Reference Barro, Ursúa and Weng2020; Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Shapiro, Sudhof and Wilson2020; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Igan, Pierri and Presbitero2020; Chronopoulos et al., Reference Chronopoulos, Lukas and Wilson2020; Coibion, Gorodnichenko, & Weber, Reference Coibion, Gorodnichenko and Weber2020; Deb, Furceri, Ostry, & Tawk, Reference Deb, Furceri, Ostry and Tawk2020; Fernández-Villaverde & Jones, Reference Fernández-Villaverde and Jones2020; Fetzer, Hensel, Hermle, & Roth, Reference Fetzer, Hensel, Hermle and Roth2020; Goolsbee & Syverson, Reference Goolsbee and Syverson2021; Kanapickiene, Reference Kanapickiene, Teresiene, Budriene, Keliuotytė-Staniulėnienė and Kartasova2020; Kok, Reference Kok2020; König & Winkler, Reference König and Winkler2020, Reference König and Winkler2021; Lee, Reference Lee2020; Maloney & Taskin, Reference Maloney and Taskin2020; Pavlyshenko, Reference Pavlyshenko2020; van der Wielen & Barrios, Reference van der Wielen and Barrios2020; Vasiljeva et al., Reference Vasiljeva, Neskorodieva, Ponkratov, Kuznetsov, Ivlev, Ivleva and Zekiy2020; Verma et al., Reference Verma, Dumka, Bhardwaj, Ashok, Kestwal and Kumar2021; among others). Overall, this literature shows that COVID shock and the crisis-induced constraints drastically affected economic activity, performance of financial markets, households’ economic sentiment, and business confidence. However, most of these studies concentrate on a few countries (or regions, namely, the United States and Europe and some studies also on China), hence lacking a global view. Therefore, there is still a need for international analyses. We contribute to this literature by (i) being the first to analyze both the direct and spillover effects of the COVID shock on business confidence; (ii) taking a global perspective.

We now detail the specific hypotheses we test in this article. Specifically, the hypotheses will build on three aspects: the overall direct impact of the containment measures to mitigate the COVID pandemic on business confidence; the heterogeneous direct impact of the containment measures distinguishing between emerging and advanced economies; and the spillover effects of the containment measures, accounting for geographic, economic and administrative, and cultural linkages among countries.

Overall Impact of the COVID Pandemic on BCI

While the pandemic has had a widespread effect in all countries, the response to this problem that each State has chosen differs: Some countries have had mandatory containment regulations from the beginning of the pandemic, others have implemented fewer compulsory containment measures leaving space for self-regulation of their citizens. Also, each society has reacted differently to these diverse policies. Yet, how these measures have impacted business confidence is still not completely clear. We aim at contributing to this literature by testing the extent to which more or less interventionist containment measures in the economy and in society have affected the disposition of executives to increase or decrease their investments and activities, as reflected in their expectations about the future.

More generally, there is a long-standing debate about the role of the State and how it affects the overall performance of firms. While some scholars emphasize the negative effects of State intervention (as it distorts market rules and/or provides wrong incentives and signals to firms; Dharwadkar, George, & Brandes, Reference Dharwadkar, George and Brandes2000; Kornai, Reference Kornai1990; Megginson & Netter, Reference Megginson and Netter2001), several studies also illustrate how State intervention can help firms and complement their investments (Cui & Jiang, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Finchelstein, Reference Finchelstein2017; Heugens, Sauerwald, Turturea, & van Essen, Reference Heugens, Sauerwald, Turturea and van Essen2020; Lazzarini & Musacchio, Reference Lazzarini and Musacchio2018). Usually, the role of the government and its effect on business decisions is assessed by examining a specific set of policies. In contrast, the uniqueness of the COVID pandemic allows us to test a broad set of containment policies, which have had a considerable impact on business activities.

On the one hand, investors and business people could view the containment measures as positive. This is because these measures help mitigate the spread of the COVID disease in the medium and long term, thus creating a more auspicious future perspective for businesses. On the other hand, the economic impact in the short term is negative as these containment measures imply a sharp reduction of business activity. Which one has a stronger effect? We hypothesize that under a widespread crisis such as the COVID pandemic, business people might be inclined to pay more attention to the intrinsic negative factors affecting them in the short term. Several empirical studies show that under unstable scenarios, the intertemporal horizon of investments decreases (Gulen & Ion, Reference Gulen and Ion2015; Julio & Yook, Reference Julio and Yook2012; Kosacoff & Ramos, Reference Kosacoff and Ramos2006). Thus, we make the hypothesis that the negative short-term effects of the containment measures on BCI may be greater than the positive medium-term (and long-term) factors. Therefore, our first hypothesis is the following:

Hypothesis 1: The (compulsory and voluntary) containment measures to mitigate the COVID pandemic have decreased the overall confidence of investors.

If Hypothesis 1 is corroborated, a second important question relates to the effect on BCI of the compulsory containment policies relative to the voluntary ones. Have compulsory containment measures had a greater negative effect on BCI than voluntary ones? There are two elements to take into consideration to hypothesize an answer to this question. First, there is evidence showing that the compulsory containment measures have had larger short-term negative effects on economic activity (relative to the voluntary ones, Ambrocio, Reference Ambrocio2021). Second, investors may face greater uncertainty about how long the compulsory containment measures are going to last (compared to the voluntary measures that people in a decentralized way decide to take or not). Given the elements above, our second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2: The direct negative effect on BCI of the compulsory containment measures has been larger than the impact of the voluntary containment measures.

Note that, while the voluntary and compulsory containment measures should both have a negative effect on economic activity and business confidence, if Hypothesis 1 is confirmed, Hypothesis 2 is arguing that the direct impact on BCI of the compulsory containment measures is expected to be larger than the effects of the voluntary ones.

Advanced versus Emerging Economies

When we think about the impact of previous exogenous shocks (e.g., terrorism, natural disasters, among others), in most of the cases, the effects were regional; thus, comparisons between countries were limited by this regional scope. In contrast, the COVID exogenous shock has a widespread effect all over the globe. It hence allows us to compare its effects between different sets of countries. In particular, we are interested in the distinct effect that the COVID pandemic has in emerging economies with respect to advanced ones. Scholars in the field of development economics, sociology, and political science have proposed various explanations for how and why countries grow and develop. Within this wide group of studies, there are institutionally based explanations (North, Reference North1990; Pierson & Skocpol, Reference Pierson and Skocpol2002; Thelen, Reference Thelen2004), some based on countries’ legal origins (La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, Reference La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny1997), or geography (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2002; Acemoglu & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Gallup, Sachs, & Mellinger, Reference Gallup, Sachs and Mellinger1999). There are also studies that highlight certain key variables of countries’ social structure and their past (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2005; Han & Paik, Reference Han and Paik2017; Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2010; Zorn, Dobbin, Dierkes, & Kwok, Reference Zorn, Dobbin, Dierkes and Kwok2005), such as the role of managers in society, origins of the colonial structure, and ethnic diversity, among others. Most of these studies agree that there is a path dependence (Mahoney, Reference Mahoney2000; Pierson, Reference Pierson1997) that reinforces and consolidates the key features of this development path. Yet, exogenous shocks can alter this tendency, generate new conditions and might even create a new route. It is still to be seen what will be the actual long-term effects of the COVID shock on countries’ development. In this article, we aim at contributing to this area of research by examining the following two dimensions: (i) whether the containment measures have been stricter in emerging economies relative to advanced economies; (ii) whether the short- and medium-term impact on BCI of these containment measures has been different in emerging economies relative to advanced ones.

To hypothesize an answer to the first of these dimensions of study, there are several elements to consider. First, it is important to acknowledge that there is considerable variation within emerging and advanced economies. For instance, Brazil and Argentina are two emerging economies that have followed very different public policies to contain the spread of COVID. By the same token, governments in two advanced economies such as France and Sweden have taken very different measures to deal with the COVID pandemic. Second, the ideological standpoint of each country, the cultural values that each society has (e.g., regarding individual freedom versus collective responsibility), and the political orientation of the party in power may be additional important factors explaining the differences in the intensity of the voluntary and compulsory containment measures taken in the various emerging and advanced countries. However, from the previous two elements, it is not possible to hypothesize whether the compulsory containment measures have been more or less severe in emerging economies, relative to advanced economies.

Third, from an economic standpoint, advanced economies may be better prepared to handle the COVID pandemic, in comparison to emerging economies: better infrastructure, larger fiscal budgets, more financial resources to make counter-cyclical policies to deal with the economic fall, and more developed health care systems and social programs to contain the COVID disease, should provide advanced economies with better material capabilities to face the challenging times created by the COVID pandemic. Additionally, their greater technological capabilities should work in their favor. A clear example of the latter refers to their capabilities to produce the COVID vaccine. According to this interpretation, one could expect that the containment measures that advanced economies needed to implement to mitigate the effects of the COVID pandemic may have been less severe, relative to the measures taken in emerging economies. On the other extreme, emerging economies might also have reasons to avoid implementing strict containment measures. To begin with, implementing strict containment measures might lead to lower tax collection. As governments in emerging economies usually have weaker fiscal balances, measures reducing their fiscal resources might be disregarded. Second, the institutional characteristics of emerging economies may be an additional factor that could discourage them from applying strict containment measures. Precisely, applying strict containment measures requires having a group of qualified bureaucrats being able to design these containment measures and to enforce them. Third, some emerging economies have experience handling previous pandemics in the past (i.e., Ghana and Rwanda), such as Ebola or SARS. This past experience may have encouraged these countries to deal with the COVID pandemic without the need to implement strict containment measures. Nevertheless, in comparison to advanced economies, emerging ones have weaker institutions (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson and Thaicharoen2003; Brinks et al., Reference Brinks, Levitsky and Murillo2019) and bureaucracies (Rauch & Evans, Reference Rauch and Evans2000), and poor enforcement controls (Spiller & Tommasi, Reference Spiller and Tommasi2008). Hence, when these countries assess the feasibility of implementing strict containment measures, they may realize that (even if they want to) they are unable to execute them.

In this article, we hypothesize that the economic factors (namely fewer material capabilities of emerging economies, relative to advanced economies) are the strongest ones. As a result, our third hypothesis reads as follows:

Hypothesis 3: The containment measures that advanced economies have implemented to mitigate the effects of COVID pandemic have been less severe, relative to the measures taken in emerging economies.

Concerning the second dimension of study (namely, the differential effect on BCI of the containment measures taken in emerging and advanced economies), we hypothesize that there are reasons to expect a better response of business people in emerging economies, relative to advanced economies. To begin with, economic growth rates are usually more volatile in emerging economies (with higher ups and downs), thus allowing for a potential faster recovery. Second, emerging economies typically exhibit a greater level of instability and uncertainty. As an illustration of this, Henisz et al. (Reference Henisz, Mansfield and Von Glinow2010) show that several studies could not find a significant statistical relation between higher country risk or uncertainty and investment levels. Third, business people operating in emerging economies are more used to uncertainty, fluctuations, and sudden and drastic changes in public policies (Aguilera et al., Reference Aguilera, Ciravegna, Cuervo-Cazurra and Gonzalez-Perez2017; Aulakh, Reference Aulakh2007; Casanova, Miroux, & Finchelstein Reference Casanova, Miroux and Finchelstein2021; Cuervo-Cazurra & Ramamurti, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra and Ramamurti2014; Cuervo-Cazurra et al., Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Carneiro, Finchelstein, Duran, Gonzalez-Perez, Montoya and Newburry2019; Guillén & García-Canal, Reference Guillén and García-Canal2012). As a result of the above, one could argue that business people in emerging markets may have developed a different set of skills and a distinct mindset. Supporting this idea, Casanova et al. (Reference Casanova, Miroux and Finchelstein2021) show that e-commerce companies in emerging markets have relied on their flexibility and adaptation skills to succeed in business. Finchelstein (Reference Finchelstein2017) assesses how the different public policies and a more constrained access to capital markets condition the type of international strategy chosen by Latin American firms. By the same token, Cuervo-Cazurra et al. (Reference Cuervo-Cazurra, Carneiro, Finchelstein, Duran, Gonzalez-Perez, Montoya and Newburry2019) examine specific international strategies (i.e., tropicalized innovation) and distinguish the autonomous strategies of emerging markets companies. In short, several studies argue that emerging markets’ conditions shape business people's strategies. Hence, it is reasonable to expect that their reaction to a political, economic, or social shock can be different from the one experienced by business people in advanced economies.

From the elements above, we expect that the COVID pandemic would have had a smaller effect on the expectations and willingness to invest of business people in emerging markets. Consequently, we propose the following fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: The containment measures to mitigate the COVID pandemic have had a smaller direct impact on the BCI of emerging economies than that of advanced ones.

Spillover Effects

We now focus on the compulsory containment measures. In addition to investors’ direct reaction to the compulsory containment measures taken by their domestic governments, we take a novel approach and examine how investors and business people react to the compulsory containment policies taken by neighboring countries. We consider a broad conceptualization of neighboring countries that implies considering the geographic and cultural ties between countries, as well as their economic and administrative proximity.

Intuitively, in the case of geographic proximity, we aim at capturing that people in a given country are more likely to be sensitive to the containment measures taken in nearby countries (in terms of distance), for example, because of tourism and migration linkages, which should be stronger between neighboring countries. In turn, the economic and administrative proximity refers to the linkages between countries (due to, for instance, free trade agreements or sharing the currencies) that encourage them to trade and that foster corporations in these ‘similar' countries to work together (through trade or transfer of technology). Lastly, cultural proximity aims at capturing similarities between countries regarding religious beliefs, race, ethnicity, language, and social norms and values. These collections of beliefs, values, and social norms shape the behavior of individuals and organizations (Ghemawat, Reference Ghemawat2001, September); hence, it is more likely that organizations in a given country i might be more sensitive to the containment measures taken by a country to which country i is culturally linked.

Studying the spillover effects of the containment measures is important because it enlightens us on whether business people are reluctant to the overall idea of compulsory containment measures beyond the ones that are specifically directed to them. One first hypothesis is that investors are not against these measures per se but rather that they become more pessimistic about the future (and hence, hesitant on investing) when these restrictive measures directly apply to them. What is more, given the positive effects on public health and on the smaller global propagation of the disease when stricter compulsory containment measures are applied somewhere, one should expect that investors would be more optimistic about the future (and hence, be more inclined to invest) if neighboring countries (as defined above) do implement these measures. This would be because these decisions indirectly benefit them.

A second alternative possible interpretation would be that business people's expectations become more pessimistic when neighboring countries implement stricter containment measures. This is because the measures taken in other neighboring countries would indicate that the COVID pandemic has expanded, thus making them realize that the consequences of the COVID crisis are larger than what was initially expected by them. In the end, it is an empirical question to determine which of these two forces prevail. Since we consider that the first interpretation is the most likely to be true, our fifth hypothesis reads as follows:

Hypothesis 5: Compulsory containment measures taken by neighboring countries have a positive effect on the BCI.

Intuitively, what Hypotheses 1, 2, and 5 together are reflecting (if confirmed) is the well-known concept in economics of a positive externality, which occurs when taking an action benefits third parties. In our words, business people and investors in a country do not have the incentives to fully pay the costs of the measure (the measure being the containment measure and costs, the negative impact on economic activity). Hence, they become less optimistic about the future when these policies are implemented in their own countries. This is because business people cannot fully profit from the total world benefits of the measure (e.g., in terms of public health), which are larger than the benefits for the country implementing it. In contrast, when the compulsory measures are taken elsewhere, investors can profit from the total world benefits of these policies, without paying the costs. Therefore, investors would become more optimistic.

METHODS

We now describe the methodology and data we use to study the impact of the COVID shock on business confidence. We first present the baseline model specification, together with the data. Then, we describe how we measure the spillover effects on business confidence of the containment measures taken in the countries that are geographically, economically and administratively, and culturally linked to a given country i (Hypothesis 5). For the latter, we define and quantify the three sources of proximity between countries, namely, geographic, economic and administrative, and cultural proximity.

Consider N countries over T periods. Denote by yt the vector of business confidence indicators at period t ∈ T. The benchmark model specification writes as:

where α is the intercept, Xt−1 denotes a matrix of k lagged country-specific macroeconomic and pandemic variables and β the vector of their k parameters. In addition, μ is a vector of country-fixed effects. We assume that the error terms v i,t ∈ vt are identically and independently distributed with mean 0 and variance $\sigma _i^2$![]() .

.

To proxy for business confidence (vector yt in equation (1)), we rely on the monthly standardized business confidence indicator, which source is OECD (2021a).Footnote [5] This choice is built on the literature showing that BCI provides a dynamic view of the economy and that it is a good indicator to anticipate changes in the business cycles (Dajčman, Reference Dajčman2020; Khan & Upadhayaya, Reference Khan and Upadhayaya2020; Konstantinou & Tagkalakis, Reference Konstantinou and Tagkalakis2011; Taylor & McNabb, Reference Taylor and McNabb2007). We consider the standardized version of the BCI for comparison across countries and through time. The period of analysis is January 2018–December 2020. We have a sample of 43Footnote [6] countries, 12 of which are emerging economies.

Regarding the country-specific macro-economic and pandemic variables in Xt−1, we follow the literature on business confidence (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Favero and Giavazzi2015; Dajčman, Reference Dajčman2020; Khan & Upadhayaya, Reference Khan and Upadhayaya2020; Konstantinou & Tagkalakis, Reference Konstantinou and Tagkalakis2011; Pranesh et al., Reference Pranesh, Balasubramanian and Mohan2017; Taylor McNabb, Reference Taylor and McNabb2007) and recent studies on the impact of the COVID shock on economic activity (Ambrocio, Reference Ambrocio2021; Baek et al., Reference Baek, McCrory, Messer and Mui2020; Deb et al., Reference Deb, Furceri, Ostry and Tawk2020; Fernández-Villaverde & Jones, Reference Fernández-Villaverde and Jones2020; Goolsbee & Syverson, Reference Goolsbee and Syverson2021; König & Winkler, Reference König and Winkler2021; Maloney & Taskin, Reference Maloney and Taskin2020). As macroeconomic factors, we consider variables capturing the stance of fiscal and monetary policy, with the proxies being the quarterly general government final consumption as a proportion of GDP (source: OECD) and the monthly Central Bank policy interest rate (end of period, percent per year, in real terms, source: Bank for International Settlements), respectively. The pandemic variables include the following: Containment measures taken by national governments, with this being a proxy for the severity of the compulsory government policies aimed at restricting activities during the pandemic (source: Oxford COVID government response tracker); the number of deaths per million of inhabitants, which is a proxy for the voluntary containment measures that the population has chosen to take (Goolsbee & Syverson, Reference Goolsbee and Syverson2021; Kok, Reference Kok2020; König & Winkler, Reference König and Winkler2021, Reference König and Winkler2020; Maloney & Taskin, Reference Maloney and Taskin2020; Yan, Malik, Bayham, Fenichel, Couzens, & Omer, Reference Yan, Malik, Bayham, Fenichel, Couzens and Omer2021, source: Our World in Data);Footnote [7], Footnote [8] a trend variable capturing the number of days since the 100th COVID case in a country (Sorci, Faivre, & Morand, Reference Sorci, Faivre and Morand2020; Yilmazkuday, 2021; source: Our World in Data); an interaction term between deaths per million of inhabitants and the trend variable, this is to capture any non-linearities possibly present in the data. In addition, in some model specifications, we include a (country-specific) dummy variable for the pandemic period, which takes the value of one since the 100th coronavirus case was registered. We rely on this indicator variable to allow for specific coefficients of certain variables (e.g., when analyzing the impact on BCI of the stance of the fiscal and monetary policy). It is important to add that by allowing for time varying containment measures, we are able to account for dynamic changes in the COVID situation of the countries and the public policies to contain the pandemic.

To conduct some robustness checks, we include the following additional pieces of information. First, we include health expenditure as a proportion of GDP. Health expenditure measures the final consumption of health care goods and services (i.e., current health expenditure) including personal health care and collective services (prevention and public health services as well as health administration), but excluding health investments (OECD, 2021b). Second, we incorporate the information on trust in government. This variable measures the percentage of people who respond having confidence in the national government (OECD, 2021c). Third, we include the country-specific Pandemic Uncertainty Index, which is constructed by counting the number of times uncertainty is mentioned within a proximity to a word related to pandemics in the Economist Intelligence Unit country reports (Ahir, Bloom, & Furceri, Reference Ahir, Bloom and Furceri2018). Fourth, to capture the role of institutional and political arrangements observed in the different countries in our sample, we include, as controls, a categorical variable for whether the country has a presidential or parliamentary system (Cruz, Keefer, & Scartascini, Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2021); a categorical variable to indicate if the political party in power has a right, center, or left orientation (Cruz et al., Reference Cruz, Keefer and Scartascini2021); the first principal component of the World Governance Indicators (with the indicators being government effectiveness, political stability, rule of law, control of corruption; World Bank) and the first principal component of some of the dimensions forming the economic freedom index (namely, judicial effectiveness, business freedom, monetary freedom, trade freedom, investment freedom, and financial freedom; source: Heritage).

Fifth, following the related literature (Ambrocio, Reference Ambrocio2021; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Lee, Dong and Taniguchi2021; Deb et al., Reference Deb, Furceri, Ostry and Tawk2020; Kok, Reference Kok2020), we add additional expenditures and forgone revenue in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as a proportion of total GDP (Fiscal monitor database of country fiscal measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, n.d.). The additional spending variable measures the level of economic assistance provided by the government to lessen the economic damage during the COVID pandemic. Last, to account for global factors, in unreported results, we include the US Federal Reserve target rate (mid-point) (Bank for International Settlements), lagged one month, as a proxy for the world stance of monetary policy. Note that in the case of variables that have a daily frequency (namely, the containment measure, the number of deaths per million of inhabitants, the country-specific COVID trend, and the indicator variable for the pandemic), for the estimations, we consider the values of each variable on day 15 of each month. The complete dataset supporting this study's analysis is available in Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/dpja6/?view˙only=228175c8afb54114a76c351974b0b39c

To mitigate any endogeneity bias due to simultaneity, all country-specific macroeconomic variables and the institutional and political controls are lagged by one period, which corresponds to one month or one quarter, depending on the frequency of the variable. Table 1 describes in more detail the macroeconomic and pandemic variables, together with the institutional and political controls. It also provides the frequencies and sources of each factor. Table 2 exhibits the descriptive statistics of the dependent and explanatory variables. Table 3, in turn, reports the correlation matrix between all the previously mentioned variables.

Table 1. Variables’ description

Notes: We lag and standardize the following variables: Comp Containment, Economic Support, Mon Policy Rate, and Gov Consumption; the time lag is a period of one month or one quarter, depending on the variable's frequency. Additionally, we standardize Deaths/Million. BCI stands for business confidence index; Comp Containment stands for the compulsory containment measure; Gov Consumption and Gov System refers to government consumption and government system; Pol Orientation stands for political orientation. Mon Policy Rate means monetary policy interest rate; Com is the abbreviation for common and Lang is the abbreviation for language; FPC stands for first principal component; Govce Ind stands for governance indicators and Eco Freedom refers to economic freedom. Trust in Gov stands for trust in government; PUI is the acronym of the pandemic uncertainty index; Add Exp stands for additional expenditure; Health Exp means health expenditure. We lag FPC Govce Ind and FPC Eco Freedom one period. (1) Our World in Data is a project of the Global Change Data Lab, a non-profit organization. It is sponsored by the University of Oxford, whose research team is affiliated to the Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development. CEPII refers to ‘The Centre d’Éudes Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales’, in English, Center of Prospective Studies and of International Information. OECD is the abbreviation for organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. IMF is the International Monetary Fund. IDB stands for Inter-American Development Bank. BIS refers to the Bank for International Settlements.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the dependent and explanatory variables

Notes: All descriptive statistics correspond to the period 2018–2020. Std. Dev, P25, and P75 are the standard deviation, the first and third quartile of the empirical distribution of the corresponding variable, respectively. We lag the following variables: Comp Containment, Mon Policy Rate, and Gov Consumption; the time lag is a period of one month or one quarter, depending on the variable's frequency. BCI stands for business confidence index. Pandemic is a (country-specific) dummy variable that takes the value of one since the 100th coronavirus case is registered. Deaths/Million corresponds to the deaths per million of inhabitants and Trend, to the trend pandemic variable after the 100th COVID case is registered. Comp Containment stands for the compulsory containment measure. Mon Policy Rate corresponds to the real monetary policy interest rate. Gov Consumption refers to general government final consumption as a proportion of GDP. Development is a binary variable that takes the value of one for advanced economies, and zero (base category) for emerging countries. Gov System describes the government system (presidential or parliamentary system). Trust in Gov stands for trust in government. The first principal component (FPC) of the governance indicators and economic freedom variables are named FPC Govce Ind and FPC Eco Freedom, respectively. We lag FPC Govce Ind and FPC Eco Freedom one period. PUI is the acronym of pandemic uncertainty index.

Table 3. Correlation matrix of the dependent and explanatory variables

Notes: We lag and standardize the following variables: Comp Containment, Mon Policy Rate, and Gov Consumption; the time lag is a period of one month or one quarter, depending on the variable's frequency. Additionally, we standardize Deaths/Million. We lag FPC Govce Ind and FPC Eco Freedom one year. Deaths/Million corresponds to the deaths per million of inhabitants and Trend, to the trend pandemic variable after the 100th COVID case is registered. Comp Containment stands for the compulsory containment measure. Mon Policy Rate corresponds to the real monetary policy interest rate. Gov Consumption refers to general government final consumption as a proportion of GDP. Trust in Gov stands for trust in government. The first principal component (FPC) of the governance indicators and economic freedom variables are named FPC Govce Ind and FPC Eco Freedom, respectively. PUI is the acronym of pandemic uncertainty index.

To examine the spillover effects of the compulsory containment measures taken in different countries, we build three proximity or spatial weight matrices, to proxy for the three sources of proximity between countries that we consider in this article, namely, the geographic, economic and administrative, and cultural proximity. These three sources of proximity are inspired by the work of Ghemawat (Reference Ghemawat2001, September), who developed the CAGE distance framework to identify and prioritize the differences between countries that companies must address when developing cross-border strategies. The dimensions that the author considers are precisely the geographic, economic, administrative, and cultural proximity.

More specifically, each value in any of the three proximity matrices corresponds to a pair of countries and indicates whether the two countries in a given pair relate to each other in geographic, economic and administrative, or cultural terms. We then use these three matrices to compute the average compulsory containment measures taken in the countries related to a given country i in geographic, economic (and administrative), or cultural terms. Precisely, we compute the average compulsory containment measures implemented in the countries being in the geographic neighborhood of a given country i (geographic proximity), the mean compulsory containment measures of countries that are economically and administratively related to country i (in short, economic proximity), and the average compulsory containment measures implemented in the countries which are culturally linked to country i (cultural proximity). The use of spatial econometric methods to ‘spatially lag the containment measures’ is appealing since it enables us to analyze the spillover mechanisms stemming from multiple sources of transmission of shocks across countries in a single model, with multiple proximity matrices accounting for these various sources of economic propagation of the COVID shock. The model specification accounting for the spillover effects of the containment measures is:

where Ct−1 contains the lagged vector of containment measures taken in different countries at period t; $\bar {{\bf C}}_{t-1}$![]() is the cross-sectional average of the lagged containment measures taken in different countries at period t; Wp represents a proximity matrix of size N × N, p is the sub-index for the three sources of proximity, namely, the geographic (sub-index p = G), the economic and the administrative (in short, p = E), and the cultural (p = C) channels; hence, $p\in {\cal P}$

is the cross-sectional average of the lagged containment measures taken in different countries at period t; Wp represents a proximity matrix of size N × N, p is the sub-index for the three sources of proximity, namely, the geographic (sub-index p = G), the economic and the administrative (in short, p = E), and the cultural (p = C) channels; hence, $p\in {\cal P}$![]() and ${\cal P} = \{ G;\; E;\; C\}$

and ${\cal P} = \{ G;\; E;\; C\}$![]() . Thus, an element of Wp, which we denote by w p,i : j, represents the extent of the corresponding proximity between two given countries i and j. Also, we impose that w p,i : i = 0, or equivalently, that each diagonal element in each Wp is zero. This is important since by construction, countries cannot be connected with themselves. Note that the ‘domestic' compulsory containment measure appears in Xt−1. Conversely, if two different countries i and j are linked in geographic, economic and administrative, or cultural terms, then w p,i : j = 1; otherwise, w p,i : j = 0. Next, we row-normalize. The parameters ρ p will hence capture the average intensity of the containment measures in the countries that have geographic, economic (and administrative), or cultural proximity with country i (depending on the sub-index p). Sections ‘Geographic Linkages’, ‘Economic and Administrative Linkages’, and ‘Cultural Linkages’ detail the construction of the matrices for geographic, economic (and administrative), and cultural proximity (WG, WE and WC) respectively.

. Thus, an element of Wp, which we denote by w p,i : j, represents the extent of the corresponding proximity between two given countries i and j. Also, we impose that w p,i : i = 0, or equivalently, that each diagonal element in each Wp is zero. This is important since by construction, countries cannot be connected with themselves. Note that the ‘domestic' compulsory containment measure appears in Xt−1. Conversely, if two different countries i and j are linked in geographic, economic and administrative, or cultural terms, then w p,i : j = 1; otherwise, w p,i : j = 0. Next, we row-normalize. The parameters ρ p will hence capture the average intensity of the containment measures in the countries that have geographic, economic (and administrative), or cultural proximity with country i (depending on the sub-index p). Sections ‘Geographic Linkages’, ‘Economic and Administrative Linkages’, and ‘Cultural Linkages’ detail the construction of the matrices for geographic, economic (and administrative), and cultural proximity (WG, WE and WC) respectively.

Geographic Linkages

To measure geographic proximity for each country in our sample, we first identify the five nearest neighboring countries, by computing the distances between the most populated cities in the two countries of a given pair. We then define that an element w G,ij in the proximity matrix WG equals one if country j is one of the five nearest neighbors of country i. Last, we row-normalize the resulting adjacency matrix.

Economic and Administrative Linkages

As explained above, the economic and administrative proximity refers to the linkages between countries that result, for example, in them trading with each other. In this respect, historical associations between countries (such as free trade agreements; sharing the currency; similarities of countries regarding the levels of corruption; and the countries’ size, among others) significantly affect the exchange between countries. We now detail our procedure to identify the economic and administrative linkages.

First, relying on annual bilateral export and import data for the period 2013−2017 (Direction of Trade Statistics, DOTS), we compute the trade intensity measure z ij,t as:

where EX ij,t (IM ij,t) refers to exports (imports) from country i to country j in year t, and GDP i,t stands for the Gross Domestic Product of country i in year t.Footnote [9]

Second, we instrument the trade intensity measure, relying on standard variables used in the trade literature (Cavallo & Frankel, Reference Cavallo and Frankel2008; Frankel & Romer, Reference Frankel and Romer1999; Frankel & Rose, Reference Frankel and Rose2002; Rose, Lockwood, & Quah, Reference Rose, Lockwood and Quah2000). We instrument bilateral trade to account for the possibility of trade being endogenous.Footnote [10] Specifically, as instrument variables, we consider the log of the product of the land areas of the two countries in a given pair, the log of the product of the population of the two countries, indicator variables for whether the two countries in a pair are landlocked, whether they share the currency, whether they have at least one contiguous border, whether they are part of a free trade agreement, and a similarity measure between countries regarding corruption. We measure similarity between countries in terms of their exposure to corruption (Ghemawat, Reference Ghemawat2001, September), $Simil_{i\, \colon \, j}^{r}$![]() as follows:

as follows:

where r i,t and r j,t are the values at time t of the corruption index (ICRG) for countries i and j, respectively.

Specifically, to instrument the trade intensity measure, we estimate the following gravity equation:

where Hij,t denotes the vector of the previously listed variables used to instrument the trade intensity measure corresponding to the country pair i, j, ϕ is a vector of parameters, δ t refers to time (year) effects, and $\varepsilon _{i, t}$![]() are the residuals. We then predict trade intensity based on equation (5), that is, $\widehat {z}_{ij, t} = {\bf H}_{ij, t} \widehat {\phi }$

are the residuals. We then predict trade intensity based on equation (5), that is, $\widehat {z}_{ij, t} = {\bf H}_{ij, t} \widehat {\phi }$![]() . Gravity estimates should provide good instrumental variables because they are based on spatial, social, and economic variables, which are plausibly exogenous (for exporters and importers) and yet, when aggregated across all bilateral trading partners, are highly correlated with a country's overall trade (Cavallo & Frankel, Reference Cavallo and Frankel2008).

. Gravity estimates should provide good instrumental variables because they are based on spatial, social, and economic variables, which are plausibly exogenous (for exporters and importers) and yet, when aggregated across all bilateral trading partners, are highly correlated with a country's overall trade (Cavallo & Frankel, Reference Cavallo and Frankel2008).

Third, we average across periods:

Finally, to compute the non-zero elements of WE, we identify the five largest trade partners of each country i in our sample, based on $\bar {\widehat {z}}_{ij}$![]() . An element w E,ij equals one when country j is one of the five largest trade partners of country i. We then row-normalize.

. An element w E,ij equals one when country j is one of the five largest trade partners of country i. We then row-normalize.

Cultural Linkages

To measure cultural proximity, we focus on countries that share the same language or had colonial relations in the past. Precisely, an element w C,ij of the weight matrix WC equals one if countries i and j share the same language or if they have had colonial relations in the past; otherwise, w C,ij = 0. As before, we then row-normalize. Table 1 also describes the variables used for the identification of the economic and administrative, and cultural linkages.

RESULTS

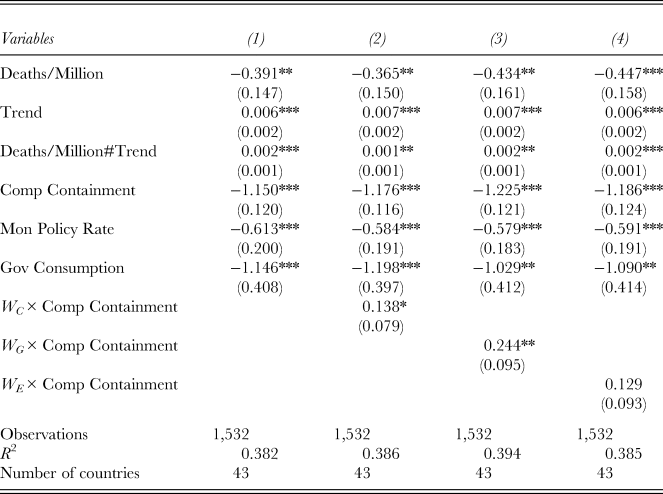

Table 4 presents the model estimates for the baseline specification in equation (1), which includes the macroeconomic and pandemic variables: Column one of results in Table 4 includes the continuous pandemic variables, that is, the proxies for the voluntary and compulsory containment measures (that is, deaths per million and the compulsory containment measure, respectively), the trend pandemic variable and the interaction term between deaths per million, and the trend. Regarding the macroeconomic determinants of BCI, we first add the monthly Central Bank policy interest rate (column two); then, we augment column two with the quarterly general government final consumption as a proportion of GDP (column three). Results are invariant to the order of entry of the macroeconomic determinants (the fiscal and monetary policy proxies). In the last column of results (column four) in Table 4, we interact the macroeconomic variables with the indicator variable for the COVID pandemic, the aim being to capture any non-linearities in the variables measuring the stance of fiscal and monetary policy, before and after the COVID shock. All estimates include country-fixed effects.

Table 4. Fixed effects, panel regression estimations of BCI: Baseline model estimates and Hypotheses 1 and 2

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. Errors are clustered at country level and all specifications include country-fixed effects. Intercept is not reported. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Deaths/Million corresponds to the deaths per million of inhabitants, and Trend, to the trend pandemic variable after the 100th COVID case is registered. Comp Containment stands for the compulsory containment measure. Mon Policy Rate corresponds to the real monetary policy interest rate. Gov Consumption refers to general government final consumption as a proportion of GDP.#denotes an interaction term. Pre-Pandemic and Pandemic indicator variables refer to the pre-COVID and COVID periods, respectively, with the latter starting when a given country registers its 100th COVID case. The R 2 that the table reports is the within R 2.

Table 4 provides strong support to Hypotheses 1 and 2. This is because it shows, first, that both (continuous) proxies for the severity of the government policies to contain the pandemic (Comp. Containment and Deaths/Million, which proxy for the compulsory and the voluntary containment measures, respectively) are statistically significant and negative, as expected. These results indicate that they have both negatively affected business confidence; they hence confirm Hypothesis 1. The way we read this finding is that when investors and business people are exposed to containment measures in their own countries, the negative short-term impact of these measures on economic activity is the most important factor (relative to the longer-term positive effects of containing the spread of the disease), thus resulting in business people being less optimistic about the future. Second, Table 4 shows that the compulsory containment measures have had a stronger negative effect on BCI, relative to the voluntary measures. Hence, it supports Hypothesis 2. This may be because of (i) the stronger negative impact that these compulsory measures have on economic activity in the short run, relative to the voluntary measures of social distance and less mobility that citizens might have decided to self-impose (Ambrocio, Reference Ambrocio2021); (ii) the uncertainty surrounding the compulsory containment measures, as people cannot anticipate when they are going to finish.

Furthermore, the coefficient estimates for the country-specific trend variable (capturing the number of days since the 100th COVID case in a country) and for the interaction term between deaths per million of inhabitants and the trend variable are both positive and significant. The way to interpret these results is that while the containment measures have a strongly negative impact on business confidence, with time, these measures may be perceived as less negative by investors. This is consistent with the interpretation that corporations get used to the COVID pandemic and learn how to deal with it when operating their businesses. This learning effect is an interesting implication of our findings.

In relation to the possible non-linearities in the variables measuring the stance of fiscal and monetary policy, before and during the COVID shock, we confirm that these variables tend to be significantly negative in both sub-periods (with the exception of the monetary policy rate over the pandemic period). Also, results show that their impacts may be stronger in the pre-COVID time. One way to interpret this finding is that investors are less sensitive to the stance of fiscal and monetary policy during the COVID period, because they know that governments do need to make expansionary economic policies to mitigate the negative impact of COVID on economic activity and social health. Therefore, business people become less worried about excessive expansionary fiscal and monetary policies that governments may undertake during COVID times. It is worth adding that results in Table 4 are robust to including a time trend and/or the US monetary policy rate as a global factor. Also important, our findings are robust to including as additional control variables: (i) a dummy variable for whether the country has a presidential system (if the country has a parliamentary system, the indicator variable takes a value of 0); (ii) a categorical variable measuring the political orientation of the party in power (right, center, left); (iii) the trust in government indicator; (iv) the first principal component of the World Governance Indicators; (v) the first principal component of the economic freedom indices; (vi) the World Pandemic Uncertainty Index. Table A3 in the Online Appendix exhibits the model estimates including these additional control variables, one at a time.

We now examine the evidence for Hypotheses 3 and 4. To begin with, in order to examine Hypothesis 3, Table 5 reports the mean voluntary and compulsory containment measures distinguishing between emerging and advanced economies. Furthermore, Table 5 exhibits the mean differences for emerging and advanced economies of some additional variables characterizing the countries in the two groups. Specifically, Table 5 reports the mean health expenditure (as a proportion of GDP), the average governance indicators, the mean additional expenditure (as a proportion of GDP) due to the COVID shock, the average trust in government, and the mean World Uncertainty Pandemic Index (PUI), in all cases distinguishing between the two groups of countries. In turn, Table 6 focuses on Hypothesis 4: First, it exhibits, for comparison, the model estimates in column four of Table 4, which is our baseline model specification. It then adds interaction terms between the dummy variable for advanced economies and the compulsory and voluntary containment measures, the aim being to have specific coefficients for the compulsory and the voluntary containment measures for these two groups of economies. Column three, in turn, reports specific coefficients for those countries with containment measures above and below the median containment measures.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of some explanatory variables: Hypothesis 3

Notes: All the statistics correspond to the pandemic period, defined since the 100th COVID case is registered in a given country. The column Advanced (Emerging) exhibits the mean of each variable for the group of countries classified as Advanced (Emerging). For each variable reported in the Table, Sign corresponds to the sign of the difference in mean between the group of emerging and advanced economies. For each variable reported in the Table, Signif reports the statistical significance of the mean test computed over the group of emerging and advanced economies. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Deaths/Million corresponds to the deaths per million of inhabitants. Comp Containment stands for the compulsory containment measure. Govce Ind corresponds to the mean over the world governance indicators used for the construction of FPC Govce Ind. Trust in Gov stands for trust in government, PUI, for pandemic uncertainty index. Add Exp means additional expenditure, and Health Exp is the abbreviation for health expenditure.

Table 6. Fixed effects, panel regression estimations of BCI: Hypothesis 4

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. Errors are clustered at country level and all specifications include country-fixed effects. Intercept is not reported. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Deaths/Million corresponds to the deaths per million of inhabitants and Trend, to the trend pandemic variable after the 100th COVID case is registered. Comp Containment stands for the compulsory containment measure. Mon Policy Rate corresponds to the real monetary policy interest rate. Gov Consumption refers to general government final consumption as a proportion of GDP.#denotes an interaction term. Emerging or Advanced#the containment measure refer to the interaction terms between the dummy variable for emerging or advanced economies, respectively, and the compulsory or voluntary containment measure, when corresponding. Above median or Below median#the containment measure correspond to the interaction between the indicator variable for above or below the median of the given containment measure, respectively, and the containment measure itself. The R 2 that the table reports is the within R 2.