Studies of landscape and architecture have long recognised the importance of how topography and buildings alike are etched with the evidence of their use and of the practices and ideologies that underpinned the communities that created them. This NBC looks at several volumes that focus on how infrastructure and architecture have shaped urban and rural environments, and how both public and private spaces can be constructed to reflect power and status. We begin with two volumes that focus on how the urban fabric of the ancient city influenced the daily spatial routines of inhabitants and the ways in which the architecture of Roman houses shaped the experience of their occupants.

Annette Haug and Stephanie Merten's volume, Urban practices: repopulating the ancient city, brings together 12 contributors with an interest in urban agents—which may be people, buildings or the spatial arrangement of the urban fabric—and the praxis of movement around the cityscape. Haug's introduction sets out the theoretical underpinning of the volume, which can broadly be defined as the impact of the city on inhabitants’ or visitors’ perceptions and experiences in terms of its layout, its demarcation by defensive walls and the architectural design and orientation of buildings and public spaces. All of these factors had an impact on urban practice, and, conversely, social practices could have had an important impact on the arrangement of urban space in what Haug describes as a “mutual interdependency of urban space, action, and actors” (p. 8).

Stefan Feuser (Chapter 3) considers the relationship between the urban fabric and the sea. Focusing on the juxtaposition of cultural urbanism and the natural force of the sea in liminal coastal places, Feuser explores the building activities that stabilised the shoreline to construct harbours, the reasons for changes to harbours, how these shoreline spaces were incorporated into the urban fabric and how they were perceived. There is a marked distinction between the expedient use of shallow bays as harbours, as in the case of the Late Archaic Lion harbour at Miletus, and the huge engineering projects that saw the construction of harbours in areas of less favourable coastal conditions such as at Caesarea, which were viewed as a victory over nature. Feuser notes that “while reclamation pushed the urban coast further into the sea, breakwaters integrated the sea into the urban fabric” (p. 44); in both cases the shaping of the harbour as a space that determined patterns of activity such as loading and unloading ships, building and the repair of vessels and movement by water of people was a process that required ongoing repair, adjustment and updating.

In her chapter on the production of diplomatic space in ancient Rome, Hannah Cornwell takes a broader view of the urban fabric by considering the way in which the city of Rome as a whole provided a space for the performance of international diplomacy, and how specific loci in the city were able to convey identity, power and boundaries through architectural design. Cornwell examines how the urban topography and architecture of the Forum Romanum was used to stage diplomatic relations during the Republican period (focusing on the Rhodian embassy of 167 BC) and in the early Imperial period (the Parthian diplomatic visit in AD 66). She notes that the success of diplomatic missions could be measured by the urban spaces that they were granted, or denied, access to, and that repeated and routinised procedures enacted in urban spaces reinforced both the boundaries of identity and the power of these recognised procedures.

Also focusing on the Forum Romanum, this time through the lens of architecture and human geography, is Dunia Filippi whose contribution takes Lefebvrian theory on ‘space as a production’—which posits that in creating social relations, people also create social space—and applies it to the lived, and perceived, space of the forum. Considering the dynamics between the forum as a social space and a physical space, Filippi concludes that the forum must be understood holistically as “the perceived space, the conceived space, and the lived space” (p. 111), with each of these aspects impacting on the other two in a constant dynamic development.

In the final chapter of the volume, Asja Müller explores the mutual relationship between the physical elements of a ‘space’ and the human practices enacted in it, both of which continuously influence one another. This study is rooted in a discussion of the Hellenistic Asclepieion of Cos, which Müller suggests used architectural framing to guide movement, inform perception and accentuate particular actions within the building. The contributors broadly agree that the power and influence of urban spaces are shaped by the architecture and the lived experience of the human actors who engage with the topography of the space, whether more formally in political spaces such as fora, ritually in religious environments such as that of the Asclepieion or in the everyday trading and economic life of a harbour. Space and practice in urban environments are held in a dynamic tension with the human and architectural agents exerting equal influence on one another.

Focusing on a particular architectural form—the Roman house—Hannah Platts's volume, Multisensory living in ancient Rome: power and space in Roman houses, investigates multisensorial experience in domestic dwellings, and considers the difference between houses and the ways in which the sensory experience of a dwelling could shape perceptions of power. Platts's study focuses on housing from Rome, Pompeii and Herculaneum as revealed by texts and material evidence. The first two chapters introduce the themes and theoretical approaches of the volume and discuss the different interpretations of ‘public’ and ‘private’ in the Roman world compared with our contemporary understanding of these terms. The following five chapters take the form of an architectural tour of a domestic dwelling, beginning in the street before mapping the visitor's experience of the atrium, cubiculum, kitchens and toilet. Building on an existing body of work on both the Roman domestic sphere and multisensorial approaches to archaeology, Platts's study attempts to understand “how and why individuals were able to, and interested in, affecting and modifying the sensory realm of their dwellings” (p. 14).

Chapter 3 presents case studies designed to highlight the differing experiences of multisensory events in Pompeii for occupants in dwellings that differed in their status, architectural form and location in the urban topography. The first explores the impact of gladiatorial games at the amphitheatre on the experience of householders in their domestic dwellings in terms of noise levels, lighting, smells and movement of people, and how these would vary depending on time of day or season. This study analysed four different architectural styles of housing in different locations in Pompeii: the House of the Vettii, the House of the Garden of Hercules, the House of the Marine Venus and the House of Octavius Quartio. Platts concludes that there was no single sensory experience of the gladiatorial games: the perception varied from property to property depending on the proximity to the amphitheatre and openness or screening of the architecture. A second case study, focused on the sensory experience of living next to fulleries, workshops and cookshops, considers how neighbouring businesses may have determined the spatial use of domestic dwellings, that is, with service quarters positioned closest to adjoining buildings—such as fulleries—whose function involved unpleasant odours.

The validity of claims, largely based on Vitruvius’ architectural treatise (De arch. VI. 5.1; Granger 1934), that Roman houses—particularly of the elite—were open to the wider public is challenged in Chapter 4 by a study of the openness of the atrium-tablinium. Platts finds this a much more flexible arrangement than initial readings of some ancient sources suggest, and argues for a more nuanced interpretation of the accessibility of the Roman house.

The volume challenges the traditional supremacy of sight and visual appearance in our interactions with and understanding of our surroundings and those of the inhabitants of Roman towns and cities, and it does so in a thoughtful and engaging manner informed by current theoretical thinking on multisensory perception. Platts concludes that

scholars of Roman housing should likewise re-place sight amongst the rest of the human sensorium thereby enabling other sensory experiences of touch, smell, sound and taste within the home to come to life, opening up a whole new insight into how the Roman home might have been employed as a vehicle of status display (p. 233).

Both volumes speak to the need for people to stage their surroundings and frame their position in the world by means of manipulation of landscape or architecture in its physical form or in the sensory perceptions through which it is experienced. Landscape and architecture—from the humble house to the urban topography of an imperial capital—are inscribed by ‘habitus’, by the ritual and deliberate or the everyday repetitive events of lives lived out in those spaces.

Shaping early medieval England

Our next three volumes take a fresh look at the early medieval landscape of the geographic region that is now England, in ways that challenge what we think we know about the road systems and architecture of the early medieval period.

In The ancient ways of Wessex Alexander Langlands traces the evidence for routeways of travel and communication in the early medieval period. His focus is Wessex, with the volume incorporating comparative case studies from Hampshire, Devon, Dorset and Wiltshire. The book is divided into three sections, a review of existing research (Part 1), case studies chosen for their diverse locations, geology and topography (Part 2) and a discussion that contextualises the findings of the case studies (Part 3). Langlands advocates an interdisciplinary approach to investigating early medieval route networks, which includes historical, archaeological, topographical and toponymic sources, to incorporate the diverse evidence. He argues that the crucial factor in identifying why change happens, and how communications influence that change, is understanding the “dynamic between developments in communications and wider societal and economic transition” (p. xi).

The volume begins by examining the debate around the longevity of ‘ancient’ routeways. Langlands acknowledges that there is insufficient evidence for permanent and regularly used single long-distance trackways with prehistoric origins, but questions whether we necessarily need to view them in those terms, and whether such ‘ridgeways’ and trackways are instead broader corridors of movement, sections of which were used seasonally or intermittently over generations. While it may be fanciful to imagine regular long-distance travel along the full length of some of the putative routes, regular use of local or regional stretches of them is not an unreasonable proposition. Langlands goes on to consider the debates on how far the Roman road system survived and continued in use into the early medieval period and the problems of varied preservation. He calls for the adoption of a more critical perspective that evaluates not only the ‘top-tier’ Roman roads, but also the lower-level routes whose disappearance would require people to use the ridgeways once again. The role of herepaths is also investigated in the volume; these are Saxon routes that appear to have been part of a planned road system whose purpose was rooted in defence. Other avenues of enquiry include bridges and fords, waterways and water transport systems, and an examination of which elements of these networks were exploited in medieval Wessex.

Viewing Wessex in the broader context of its position in Northern Europe, subject to all the political and economic influences that affected the continent in the early medieval period, Langlands suggests that this interdisciplinary methodology for studying travel and communication networks is transferable to other parts of Northern Europe and beyond. He concludes that we need to revise our perception of medieval roads as oceans of mud, and that previous studies’ reliance on the Roman road network to understand transport and communications in the early medieval period miss an opportunity to understand the complex network of routes, some of which may have been in existence since the Late Iron Age or even earlier. For Langlands, the “emerging network of maintained routes acting like draw strings, pulling tight together adjacent territories that had once been distinct” (p. 207) marked the point when early medieval polities were freed from the natural constraints of waterways and enjoyed increased mobility. Drawing on a vast array of archaeological, historical, topographical and place-name evidence, this detailed volume reveals the importance of the networks of routeways in shaping the political and economic landscape of what would become England.

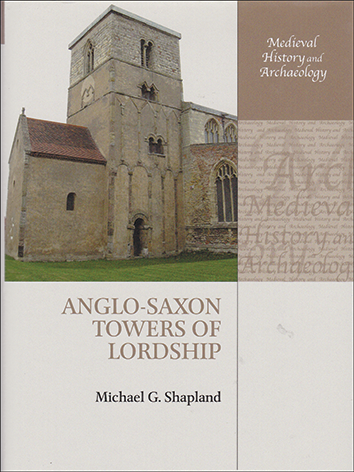

Where Langlands's volume explores the routeways and infrastructure of emerging early medieval kingdoms, Shapland's re-examines their architecture of power. Anglo-Saxon towers of lordship brings together the evidence for free-standing towers in early medieval England. These towers, essentially built for private worship, are characterised by a tiny chapel within the tower, either at its base or in an upper chamber; some had small chancels or baptistries also attached. This form of architecture dates to around the tenth to eleventh centuries AD and represents a rare opportunity to understand aristocratic architecture from the pre-Norman Conquest Anglo-Saxon period. The aim of Anglo-Saxon towers of lordship is to establish this form as a coherent architectural type and to understand why these so called ‘tower-naves’ were constructed and what they can tell us about their social, architectural and landscape contexts.

The volume is in two broad sections. Part I synthesises known sites, while Part II is an interpretation of the evidence. Shapland considers 35 tower-naves, which can be divided into two distinct categories. The first type is termed the monastic tower-nave; these are found on ecclesiastical land, often as high-status chapels, and are a reflection of the monastic reform of the tenth century. The second type is the lordly tower-nave, associated with aristocratic estates and built for private worship and as an expression of power and allegiance to God. He uses these as the focus of an investigation into the origins of this architectural form, and its spread from royal and monastic contexts to aristocratic use; the parallels with timber towers and western towers in churches; the wider role of the towers in lordly power; their military use as watchtowers; and the endurance of the tower-nave in Norman architecture. A further 14 towers are included in an appendix as ‘equivocal’ tower-naves.

Part I comprises a corpus of monastic tower-naves and lordly tower-naves respectively. Shapland's synthesis is comprehensive, including a summary of each monument with plans, elevation drawings, photographs, details of excavation and references directing the reader towards fuller reports. This section includes a discussion of the development and distribution of the towers and will prove an excellent resource for researchers. Part II delves into the origins of the tower-naves, beginning with monastic structures. Considering the earliest known tower-nave—Wilfrid's church of St Mary at Hexham dating to c. AD 705—Shapland looks for existing tower-like structures that may have inspired Wilfred's construction. In the eighth century, notable tall landmarks that may have provided inspiration would have been Roman in origin such as lighthouses and turriform temples. Shapland favours an architectural iconography approach to understanding building styles; in this school of thought, buildings do not simply copy other buildings for stylistic reasons, but because in replicating particular architectural aspects, the new building can evoke the meanings embodied in its inspirational prototype. Using this approach, Shapland considers the role of monastic tower-naves as gateways and perhaps as forerunners of the westworks of later church buildings. As high-status chapels echoing the iconography of royal authority and as mortuary chapels for high-status individuals, the tower-naves recalled the imposing style of imperial mausolea and were an architectural realisation of Jacob's Ladder. That such towers were then adopted on secular settlements reflects the later tenth-century ‘rise of the gentry’. During this time, lordly tower-naves served as physical expressions of the presence of aristocratic power and as material evidence of the devotion of the lord to the monarch and to God.

The volume certainly fulfils its aim to establish tower-nave churches as a recognisable part of the architectural repertoire of the early medieval period, and it does so in an accessible and engaging manner.

Also considering emergent representations of status is Adam McBride's volume that examines great hall complexes and their role in the formation of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The book aims to explain why these complexes were built, their development and the reason for their ultimate abandonment. The methodology is a broad comparative study of great hall complexes with contextual detail focused on the motivations for their construction in particular locations, the life of the complex and how it came to fall out of use (Part I). This is followed in Part II by a case study featuring the Upper Thames Valley that allows analysis of the socio-economic background against which we can see the emergence of supra-regional socio-political units or kingdoms, often marked by the presence of great hall complexes as can be seen at sites such as Yeavering and Long Wittenham.

Beginning by outlining the defining characteristics of the great hall complex, Chapter 2 provides descriptions of building forms. These are recognisable, first and foremost, by their monumentality, but also by the elaborate and precise form of the architecture. The chapter details wall types, foundations, associated activity and evidence for planning, before going on to consider the physical and cultural landscape settings in which great hall complexes are located. The reasons for the emergence, change and abandonment of the great hall complexes are dealt with in Chapter 3, in which, using a wealth of illustrated examples, McBride establishes that the Anglo-Saxon great hall complexes emerged as a result of fierce competition between elites and perhaps from contact with neighbouring British and Scandinavian cultures wherein similar halls had prominent roles. The author also sees the influence of the Latin Church in some of the motifs evident in these complexes, and argues for the influence of a continental European context for the development of the great hall complex. The complexes diversified over time, probably in part as a result of a shift from an emphasis on architecture to production and exchange in the material manifestation of power. The changes also coincide with more complex hierarchies and a distancing of the king from the wider populace, thus obviating the large public buildings and fostering instead more private and exclusive gathering places for elites. The abandonment of great hall complexes in the late eighth century AD is also investigated in this chapter, and McBride sees this as a deliberate move to break with the pre-Christian ‘royal package’ that included a large hall, monuments, cult activity and popular assemblies; these were abandoned as outmoded and uncivilised, and having been a central part of that package, the great hall complexes were no longer required.

McBride marshals a detailed dataset to chart the rise and fall of the Anglo-Saxon great hall as both an architectural and cultural phenomenon designed to “harness corporate power, to elicit public approval and legitimize the new power structures of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom” (p. 300). The increasing monumentalisation of these complexes kept pace with the increasing insecurity of the expanding Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. As Christianity spread, the pre-Christian ritual underpinnings of power became less important and consequently high-status buildings became privatised, making the great hall, with its iconography of power, redundant.

The volumes by Langlands, Shapland and McBride all shed new light on the shifting landscape of Anglo-Saxon England; from the importance of transport and communications networks to the use of architecture in consolidating power, it is clear that many of the socio-economic and political drivers of change in the Anglo-Saxon period are inscribed on the landscape in multiple ways. Collectively, all of the volumes considered in this NBC demonstrate how the rural and urban landscapes of the past were shaped by multiple factors: by the need for infrastructure, by communications networks but perhaps most often by the desire to express power and status, to control the experience of environments and to inhabit spaces in a conscious and deliberate way.

This list includes all books received between 1 July 2020 and 31 August 2020. Those featuring at the beginning of New Book Chronicle have, however, not been duplicated in this list. The listing of a book in this chronicle does not preclude its subsequent review in Antiquity.