In 1808, the magistrates (alcaldes) of Nóvita, a mining town in the Pacific lowlands of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, submitted a lengthy report to the governor of their province.Footnote 1 They argued that the local treasury official had tried to alter the fiscal practices observed up to then in the town by imposing sales taxes (alcabalas) on “maize, plantains, and other foodstuffs consumed by the poor.”Footnote 2 Invoking tax privileges as inhabitants of mining towns, the alcaldes remarked that the old decrees (ordenanzas) established to manage the alcabala, which had been enacted by the then Inspector-General (visitador) of the viceroyalty in 1781, “are not completely followed in this province since farming here is insufficient, and most of the foodstuffs are imported from other provinces.”Footnote 3 The alcaldes asked the governor to restore the traditional structure of the alcabala, and their petition was approved. When the treasury official appealed, the viceroy ruled in favor of the petitioners. In both instances, one of the remarks of the plea had great resonance in the authorities: “The traditions are the legitimate interpreters of the law.”Footnote 4

The attempt of Nóvita's treasury official to expand the categories of goods subject to sales taxes was one of the last efforts of the Bourbon drive to increase fiscal revenues and centralize collection across the viceroyalty. It is a good example of how tradition prevailed over reform. The magistrates of the mining town took advantage of the well-known jurisdictional fragmentation that characterized the fiscal system of the Spanish Empire. The alcabala, for instance, was, in theory, an ad valorem sales and turnover tax payable on goods, slaves, real property, and some services. Yet in some regions and cities, the tax was charged in the form of a fixed tariff (arancel) established through negotiation between the cabildos (town councils), the diputaciones (trade councils), and the cajas reales (royal treasuries).Footnote 5 Goods exempted in some regions were subject to duties in others.Footnote 6 As some scholars have argued, this fragmentation shielded the system from absolutist policies but created huge coordination problems that increased transaction costs in fiscal collection and trade flows.Footnote 7 Nonetheless, despite the Bourbons’ failures in some spheres, they successfully increased treasury revenues and changed some fiscal practices across their American dominions.Footnote 8 In western New Granada, for instance, treasury incomes roughly tripled in the 30 years that preceded the 1810 Revolution.Footnote 9

The interplay of tradition and reform has been at the core of the reexamination in the historiography of the Bourbon Reforms during the last two decades. By emphasizing the role of negotiations, political contestation, fiscal adaptations, and local and imperial contingencies, recent research has provided new empirical and analytical fuel to the field. The reform package, which had been traditionally studied as a mighty and unswerving drive toward centralization and absolutist power, is now studied within a more complex framework that includes the ways in which local, corporate initiatives shaped the process in conjunction with the fiscal and political demands of Atlantic warfare and competition.Footnote 10 The classic discussions about the “failures” and “successes” of the new dynasty have been enriched with studies about reform cycles and concrete institutional innovations that emphasize the importance of early Bourbon policy while formally testing the synergy between the reforms on one hand, and economic growth and social organization on the other.Footnote 11

Despite these novel approaches, the literature is highly compartmentalized. The historiography of the alcabala, perhaps one of the most studied duties during Bourbon rule, is a case in point. The studies tend to fall into three groups. The first privileges institutional analysis, highlighting how Bourbon reformists confronted the judicial plurality that had governed trade duties for centuries. This group of studies favors the analysis of ordinances and bureaucratic reports to track changes in sales taxes. Recent researchers have analyzed how taxpayers interpreted changes in legislation and revenue collection through concrete studies of lawsuits.Footnote 12

The second school, in contrast, focuses on the long tradition of violent reaction against sales taxes that went back to their introduction in the sixteenth century.Footnote 13 In the Bourbon Era, besides provoking several local revolts, the alcabala reform was at the center of two massive rebellions that have attracted considerable attention from historians: the rebellion of the Barrios in Quito in 1765 and the Comuneros revolt in eastern New Granada in 1781.Footnote 14 Scholars have studied the alcabalas in the context of these events, distilling from the files and trials that followed the insurrections important insights about the mechanics of trade taxes across the region.Footnote 15

The last school privileges the analysis of alcabala ledgers and records to measure trade flows and fiscal revenues.Footnote 16 The Bourbon overhaul of trade taxes was rooted in the establishment of customs houses or administrations (aduanas or administraciones) that centralized the collection of several levies. This institutional revamp left behind rich documentation that has been the main input to quantitative studies.Footnote 17 However, the use of such sources demands caution, since the nature of trade duties and account practices varied sharply even between nearby regions. Most scholars, unfortunately, have limited themselves to processing the sumarios generales (annual and monthly summaries) of sales taxes to craft time series of commodity flows. In the same vein, the literature has tended to assess the role of sales taxes in the overall revenues of the royal treasuries without breaking down the figures to grasp the impact of institutional changes on the efficiency of excise collection and tax incidence.Footnote 18

The analysis of trade taxes, in short, has shed light on different aspects of political, social, and economic change during the Bourbon rule. The mechanics of the alcabalas, however, remain poorly studied, with few historians of the three groups advocating for meaningful cross-fertilization. This article engages the literature by providing a tentative yet encompassing institutional history of sales taxes in the Northern Andes. It amalgamates lawsuits, ordinances, and logbooks to study how the reforms interacted with local customs and traditions to produce regional fiscal frameworks. This approach allows us to contribute to the field on at least three interrelated points. First, it provides novel insights into the concrete mechanisms of tax bargaining.Footnote 19 The article shows that alcabala negotiations varied sharply across the viceroyalty, with some regions relying heavily on corporate bodies (particularly the trade and city councils) to establish tariffs, while others adopted classic ways of litigation and de facto boycotts. These mechanisms of negotiation reinforced differences in rates, exemptions, and monetary arrangements that affected the Bourbon drive towards centralization, while creating little-explored conflicts between different regions regarding the impact of taxation.

Second, the article provides important corrections to the use of alcabala records to craft time series of economic activity. The article argues that only through a systematic, amalgamated comparison of the different logbooks of the customs houses is it possible to discern if the sumarios measured the level and direction of trade flows, or simply reflected changes in tax rules or bookkeeping practices. The article reinterprets data from the main North Andean entrepôts of trade to give some insights regarding fiscal cycles, real tax pressure, and tax incidence. The evidence suggests, in contrast to what the literature has contended, that the Bourbon revamp of the alcabalas experienced a boom-and-bust cycle in revenue collection, with incomes growing at impressive rates during the 1780s and 1790s, but contracting or plateauing during the 1800s. The article offers some hypotheses on how economic activity and tax bargaining may explain these patterns.

Finally, the article seeks to place the Northern Andes within the broader patterns of fiscal change across the Spanish Empire. It warns about the use of fiscal flows to measure the economic significance of a given area. The Northern Andes, traditionally considered a “peripheral” area in the context of the Spanish Atlantic, collected fewer revenues not only because of its comparatively lesser economic activity but also because the combination of tradition and reform yielded lower taxation rates and unique fiscal structures.Footnote 20 The region enjoyed the lowest alcabala rates of the empire while avoiding the cascade taxation that characterized trade flows in New Spain and other regions.

This article argues that this triad of high bargaining power, low real rates, and fiscal cycles reflected the peculiarity of North Andean political and economic structures. The polycentric connections of the region with the global economy, the bimetallic nature of its monetary structure, the fiscal competition between city councils, and the significance of inland waterways for the viceroyalty's internal trade permeated the political interaction between taxpayers, corporate bodies, and reformers. Thus, this analysis of the North Andean fiscal structures provides new venues to study the Bourbon reforms in the Americas and, hopefully, will elicit new comparative approaches in Latin American fiscal history.

The article proceeds as follows. First it considers the establishment of the aduanas and their reforms between the 1750s and 1790s. Then it examines, at the local level, the features of the different ramos (tax categories) of the customs houses and provides some forays into real tax incidence and rates. Next, the article delivers a preliminary analysis of the sumarios to compare the patterns of tax revenues in New Granada with those of other regions of the Spanish Empire. It concludes with some final remarks.

Early Reforms in Trade Taxes

The Bourbon transformation of trade taxes was a long-term effort going back to the early stages of institutional change that began with the creation of the viceroyalty in 1739. Scholars have tended to underestimate the scope of these early policies, even though very few empirical studies have been undertaken on the matter.Footnote 21 An analysis of trade taxes, however, suggests that mid-century policies, particularly the empire-wide reform led by the Marqués of Ensenada and his advocates should be taken seriously. Indeed, the revamping of sales taxes in the Northern Andes started in 1750 when the viceroy established in Bogotá the administración de alcabalas or, as it increasingly became known, the aduana de la capital. Footnote 22 Besides introducing direct administration, the customs house was to centralize the collection of sales taxes and other duties such as the camellón, a transit tax on the commodities that entered the city that was used for the maintenance of sewers and road infrastructure by the city council.Footnote 23 Before 1750, sales taxes in the capital were farmed out to merchants who resisted the crown's takeover of the tax.Footnote 24 The viceroy appointed Juan Díaz de Herrera as the first administrator and endowed him with administrative independence from the royal treasuries.Footnote 25 This independence meant, among other things, that the customs house was to have its own staff and logbooks and that only the Tribunal de Cuentas (Court of Accounts) could audit its accounts.

In 1763, the viceroy commissioned Herrera to establish administraciones in Popayán and Quito in conjunction with the establishment of the sugarcane brandy monopoly.Footnote 26 As stated above, the reform in Quito elicited an urban revolt that limited structural changes, making the transformation of Quito's alcabalas a “slow and difficult” affair.Footnote 27 There is no evidence of similar resistance to the reform in Popayán, and the administración there operated in conjunction with the liquor monopoly after 1764.Footnote 28 Yet, a report written in 1779, when the collection of the two types of duties was separated, pointed out that “since the establishment of this administración, revenues have been abnormally low despite the huge trade that this city undertakes with Quito and Santafé.”Footnote 29 As in New Spain, where the process started in 1753 in Mexico City, the expansion of direct administration in New Granada was piecemeal and subject to setbacks.Footnote 30 Even though the results were not as expected in terms of fiscal revenue and institutional change, these administraciones set the foundation for the ensuing expansion of direct administration. After all, by 1767, the crown had successfully established customs houses in the three main North Andean entrepôts.Footnote 31

Further policy expansions in the 1770s brought pivotal innovations. In Quito, the creation of a Court of Accounts in 1776, independent from that of Bogotá, reinforced the institutional setting of the customs houses since it reinforced their autonomy vis-à-vis the royal treasury.Footnote 32 In 1775, the Bogotá audiencia took another step toward centralization by drafting a specific set of rules (instrucciones generales de alcabalas) to redesign trade taxes.Footnote 33 These instrucciones, though never fully applied, show that local initiatives paved the way for those that were enacted by the inspectors-general in the 1780s.

The ordinances of 1775 sought to weaken tax farming, a method that was to be preserved only in towns with “little trade.” Even in those towns, officials were to encourage competitive bids and to avoid default by requiring guarantors. At the core of the instrucciones was the creation of a network of customs houses in each province with a single administración principal (main branch) and several subalternas (subaltern branches). The administrator of each branch was to be appointed as juez de comisos (judge of seizures), and all the disputes regarding trade taxes had to be examined by a juez conservador de rentas (judge of first instance). In the same vein, the high court proceeded to clarify tax exemptions and corporate privileges, two points on which contention had always proliferated. Finally, the members of the high court emphasized the need for regional revisions of the instrucciones since “the different conditions in each province make but impossible the application of these general dispositions in some matters and therefore they should be adapted to local circumstances.”Footnote 34

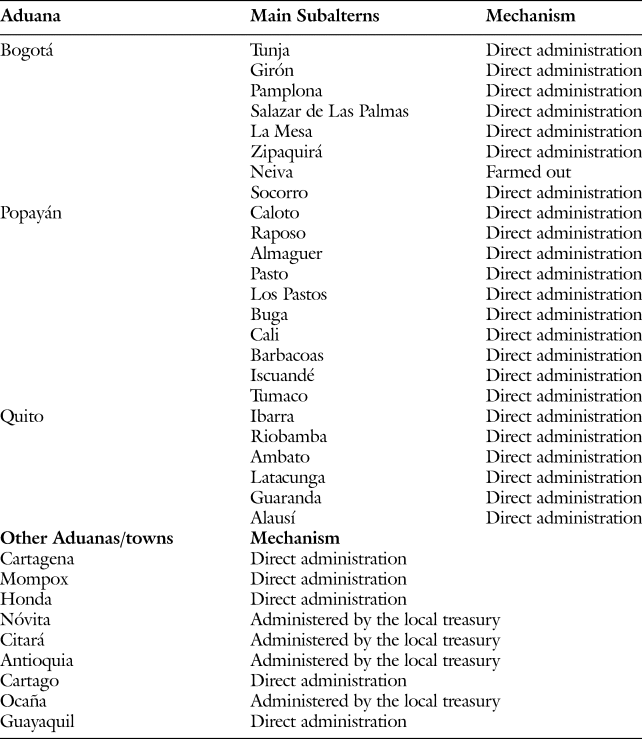

In sum, by the time the visitadores came to the viceroyalty in the late 1770s, local authorities had sketched the fundamentals of the reform: direct administration, aduana networking, clear tax liability, enforcement, and regional adaptations. On the ground, the overhaul had also advanced to encompass new regions. As Table 1 shows, by the late 1770s direct administration had been implemented in the three North Andean capitals (Bogotá, Quito, and Popayán), the main fluvial ports on the Magdalena River, and Cartagena. Nonetheless, most of the secondary markets and Guayaquil remained either farmed out or under the responsibility of the local treasury officials. Further research is needed to explore the mechanics of the alcabalas at the regional level during these early stages of the reform. For now, suffice it to say that the visitadores built upon this network of customs houses to transform trade taxes in the region radically.

Table 1 Alcabalas in the Northern Andes, ca 1779: Main Towns and Mechanism of Collection

Source: “Razón que se forma en virtud de superior decreto del Estado en que se hallan las administraciones de alcabalas de este Reino,” AGN-C, Alcabalas, tomo 5, fols. 963-977; Monserrat Fernández, La alcabala en la Audiencia de Quito, 1765–1810 (Cuenca: Casa de la Cultura, 1984), 47-49. In Pasto, the city council administered the alcabalas under a system called repartimiento, or a lump-sum payment that felt upon merchants and landowners. Note: The sources given here are also the sources for Table 4.

Enter the Visitadores

In 1778, the Bourbon overhaul of trade taxes in the viceroyalty was to experience a sweeping new phase. That year, the authorities in Madrid, led by José de Gálvez, dispatched the inspectors (visitadores generales) Juan Francisco Gutiérrez de Piñeres and José García León y Pizarro to Bogotá and Quito, respectively.Footnote 35 The mission of the inspectors was to implement the intendancy system, introduce direct administration in most of the branches of the royal treasuries, and to accomplish a political attack on the presence of local powers in the upper echelons of the royal bureaucracy.Footnote 36 The two officials were entrusted with ample political, fiscal, judicial, and military powers, which produced conflicts not only with local groups but also with the viceroy and the members of the two high courts of the viceroyalty.

The achievements of the two inspectors converged and diverged in several aspects. Both were active in addressing the fiscal needs of the Anglo-Spanish War and the broader changes in international trade policies after the application of comercio libre in 1778. They paved the way for the expansion of revenues in most of the branches of the royal treasury in the 1780s and 1790s, consolidating the aduana network and enacting new ordinances that ruled trade taxes up to the 1830s. They failed, however, to introduce the intendancy system completely and to further separate the powers of the viceroy and the audiencias. As some scholars have pointed out, these failures explain why structural changes in government were less deep-rooted in the Northern Andes than in other regions.Footnote 37

The divergences are revealing as well. According to Kenneth Andrien, León y Pizarro “succeeded in creating a strong bureaucratic state structure that helped to shape the socio-economic evolution of the kingdom [Quito] well into the early republican period.”Footnote 38 Scholars have explained León y Pizarro's success by pointing out his ability to negotiate at the local level and avoid changes in tax rates.Footnote 39 He conceived his reforms as a trade-off between increasing fiscal revenue and institutional autonomy vis-à-vis the authorities in Bogotá. In other words, he escalated fiscal pressures but promoted the autonomy of the region in financial and administrative issues.Footnote 40 In contrast, Gutiérrez's efforts achieved mixed results, disrupting the political equilibrium. The Comuneros revolt left Gutiérrez's legitimacy in tatters, and it clearly delayed and in some cases halted a good portion of his policies. What was the role of the alcabala reforms in these divergent results?

The inspectors outlined their redesign of trade taxes. The instrucciones (ordinances) for Bogotá were issued in 1781.Footnote 41 The instrucciones for Quito were completed in 1782.Footnote 42 Both ordinances incorporated many of the features of the reorganization drafted by the audiencia of Bogotá in the 1770s. The Northern Andes were divided into districts or customs houses, which were provided with professional staff and infrastructure. The director was to be bestowed not only with the faculties of the juez de comisos but also with the jurisdictional privileges of the royal officials, ratifying the creation of a judge of appeals (juez subdelegado de rentas). Each customs house, in addition, was staffed with an accountant and several functionaries responsible for the collection of taxes of the specific ramos and a resguardo, a set of guards who were to be deployed to the main entrances of the city.

The customs houses were to monitor a network of subordinate branches by auditing their ledgers and centralizing the surpluses before their final disbursement to the royal treasury. In other words, the customs houses were to act as brokers for the flow of accounts and revenues from the local level to the central level of the treasuries. Even though tax farmers were to be replaced by the new officials, the instrucciones suggested the officials keep intact the current jurisdictions unless a change in the market size of a given region created the conditions for a merger or for further division.

This institutional redesign was accompanied by changes in the very core of the regulations regarding sales taxes. The new ordinances sought to update the Recopilación de Leyes de Indias, a set of rules enacted mostly in the seventeenth century. The inspectors recognized the importance of these laws but argued that their regulations in regard to liability, fiscal practices, and rates were outdated. Yovana Celaya's analysis of the sale tax reforms in New Spain shows that in most of the lawsuits concerning the collection of the alcabala after the introduction of direct administration, taxpayers followed the instrucciones and not the Leyes de Indias.Footnote 43 In New Granada, the pattern is similar, with the ordinances slowly resolving the judicial plurality that had regulated sales taxes before 1781.Footnote 44

The instrucciones proved more systematic than the Leyes de Indias in the regulation of tax liability. They confirmed that Indigenous peoples were exempt from sales taxes but incurred liability when dealing in European goods, thereby controlling the natives who traded goods on behalf of mestizos and Spaniards attempting to avoid taxation. Gutiérrez remarked that “this is very common in this Kingdom where Indians live mixed with the Spaniards and people of color who are subject to the tax.”Footnote 45 The inspectors also discussed at length the fiscal liability of religious institutions. They kept the exemptions on goods produced for religious ceremonies and the maintenance of the Catholic clergy. However, they commanded officials to tax the private enterprises of priests. A final exemption, limited to the Quito ordinances, covered artisans, blacksmiths, shoemakers, jewelers, and other manual workers of the city. The visitador exempted them from paying the annual taxes (known as menestrales) they had been paying to keep their stores open.Footnote 46 In a city in which manufacturing and added-value activities played a vital role, this policy variation affects any attempt to measure trade flows.

The instrucciones also included a comprehensive set of clauses regulating commodity exemptions and marketplaces. Exemptions included bread, books, coins, copper weapons, and other commodities. Grains and seeds were exempted “as long as they were traded in the markets and alhóndigas (granaries) of the city.”Footnote 47 Again, this regulation was to be adjusted locally. Wheat flour, for instance, was exempt in Bogotá but was taxed in Popayán. The inspectors, however, were conscious that an overhaul of trade taxes was also to be accompanied by a reorganization of marketplaces. In the Northern Andes, there were no institutions such as the alhóndigas or pósitos that helped the city councils to intervene in markets by limiting the impacts of harvest cycles. The city councils instead resorted to price controls and export quotas. The evidence suggests that these policies during the late colonial period were slowly relaxed and, therefore, that market intervention became weaker in New Granada than in New Spain.Footnote 48 Yet, the fact that the inspectors repeatedly used the word alhóndiga and wrote several clauses on the regulation of plazas and mercados semanales, shows not only the desire to keep the wording of peninsular regulations but also the drive to regulate marketplaces.Footnote 49

Tax Categories and Rates

One of the main innovations of the inspectors was the creation of a comprehensive set of rules to organize tax categories. In Bogotá, the alcabala encompassed the following categories: efectos de Castilla (European and Asian goods), efectos de la tierra (domestic goods), pulperías (goods sold in stores), tiendas de mercaderes (retailers of European goods), ganaderos y hacendados (goods sold in the haciendas and other estates), carnicerías (slaughterhouses), eventual (movable property.), administraciones subalternas (branch offices of the customs house), arriendos (tax farmers), menestrales (artisans’ shops), deudas corrientes y de años anteriores (current and old debts), and other minor categories that taxed ecclesiastical loans (censos) and auctions (almonedas).Footnote 50 In Quito, similar tax ramos were adopted under different names, or merged into a single category. For instance, during some years, the accountants differentiated between European, Peruvian, and domestic goods, while in other years they merged them into a single category. In Quito, the ramo eventual was called ramo del viento and the ramo de ganaderos y hacendados was called cabezón general; the latter also included a tax on the obrajes (textile workshops). Both ordinances, then, outlined a thorough, sector-based approach to sales taxes that improved fiscal collection, providing empirical fuel for capturing specific streams of economic activity.

The inspectors this architecture of tax categories with specific procedures of tax collection. In this regard, three main issues are worth mentioning. First, the new ordinances reinforced the practice of levying the tax at the customs house, in anticipation of sales. The taxes on both European and domestic goods were to be cleared at the customs house, giving the alcabala certain characteristics of transit duties. Nonetheless, in contrast to the normal practice in New Spain, the movement of goods by a single merchant from one district to another did not create liability in the Northern Andes.Footnote 51 This regional transfer was subject to a second alcabala at the destination only if the goods were to be sold to a third party. Once the first alcabala had been paid at customs, the goods were supposed to be liable to a second alcabala or alcabala de reventa only on “second and subsequent sales in the same city.”Footnote 52 Despite the attempts of some officials, merchant deputies and city councils litigated heavily to maintain the exemption, avoiding the cascade effect of sales taxes that characterized other regions of the empire.Footnote 53

Second, the instrucciones established a pivotal distinction between those taxes that were to be collected ad valorem, those to be collected according to a fixed schedule, and those to be collected through assessments or lump-sum levies. European goods and transactions involving movables and real estate properties fell into the first group. This change was particularly important for the taxation of European goods in Quito, where up to 1782 the alcabala de efectos de castilla was essentially a per-unit tax.Footnote 54 Domestic goods and the fees of the slaughterhouses fell into the second group and were thus collected on a schedule. The pulperías, cabezones, and hacendados fell into the third group. The three mechanisms left plenty of room for local groups to shape rates. In addition, the ordinances preserved both the role of the city councils and guilds in the preparation of the aranceles and the negotiated nature of the annual payments made by storeowners and landowners. In other words, the instrucciones reinforced the tools for taxpayers to invoke customs and negotiations as the foundation of fiscal collection.

Finally, the inspectors implemented a system of deferred payments called conciertos, which involved contracts between the taxpayers and the administration to pay the tax in two or three installments.Footnote 55 Merchants who imported European goods worth more than 300 silver pesos had the right to defer the payment of the duties for up to 18 months in Bogotá and Popayán, and 12 months in Quito. Collection for categories such as pulperías, tiendas de mercaderes, and hacendados also followed this method. The system not only solved the liquidity problems of some taxpayers but also left behind rich documentation that, with proper methods of adjustment, can be mined to understand the market structure of the region. In sum, the visitadores designed a scheme that built on some of the piecemeal reforms that had been in the making since the 1750s and modernized the mechanics of tax collection in the region.

So far, this article has analyzed in parallel both instrucciones. Their dissimilarities, nonetheless, are revealing. One main difference is salient: tax rates. Gutiérrez sought to double rates by reviving an old tax called the armada de barlovento. Established in the 1640s, the armada was an additional sales tax of 2%. Historians have echoed the traditional narrative of the history of this tax as provided by Gutiérrez, his deputies, and its defenders. That narrative holds that the additional tax was collected regularly until 1720 when it was slowly subsumed into a single alcabala and ultimately “forgotten in the accounts of the royal treasury.”Footnote 56 However, the story is much more complicated than that. It seems that the armada was not simply forgotten or simply compounded with the alcabala. In some regions, the impost was linked to the establishment of the sisa, a consumption tax charged in Antioquia, Barbacoas, and Cartagena, and the proyecto, a transit tax charged in the ports on the Magdalena River.Footnote 57 This fact shaped the discussion of the alcabala overhaul in these regions, where ultimately different rates were adopted.

In the ports on the Pacific, such as Tumaco and Buenaventura, Gutiérrez's attempt to revive the armada was not a novelty. The royal decree that liberalized trade between New Spain, New Granada, and Peru in 1774 clarified that the armada should be charged on this trade as a separate duty from the almojarifazgo (import-export duties).Footnote 58 The businessmen of the ports took advantage of Gutiérrez's difficulties and unleashed a wave of litigation that would be settled only when the crown reduced import taxes in the Pacific ports in the early 1800s.Footnote 59

Thus, the alteration of tax rates should be read in a regional context. In Quito, Pizarro chose to keep the sales taxes at 3%. This 3% comprised 2% of the alcabala and 1% of the armada. It is not clear when and why the latter was reduced to 1%. By 1780, however, there was a sense of distinction between the two taxes, even though they were charged in conjunction.Footnote 60 Pizarro, as has been shown, focused instead on applying the 3% rate to the collection of sales taxes on European goods. In the same vein, he did not alter the exemptions for key goods, even though some of them were not sanctioned by the formal norms.Footnote 61 Gutiérrez, on the contrary, sought to impose the sales tax on cash crops such as cotton, which the smallholders in eastern New Granada used to produce textiles.Footnote 62 While Pizarro was a piecemeal reformist, Gutiérrez was, in the words of a viceregal official, an envoy who “followed the orders of Gálvez blindly.”Footnote 63

The Comuneros rebellion and other regional uprisings forced the authorities to eliminate the armada and reverse the expansion of the tax on key cash crops. The unintended consequence of the failure of this portion of the reform was that it shielded New Granada from the broader Bourbon drive to increase the rates of trade taxes. In New Spain, the alcabala reached levels of 6% to 8%. In Peru and Upper Peru, it came to 6%, and in the interior of Río de la Plata, it sat at 4%.Footnote 64 In Quito and New Granada, tax rates remained the lowest among the main regions of the Spanish Empire.

The Geography of the Alcabalas

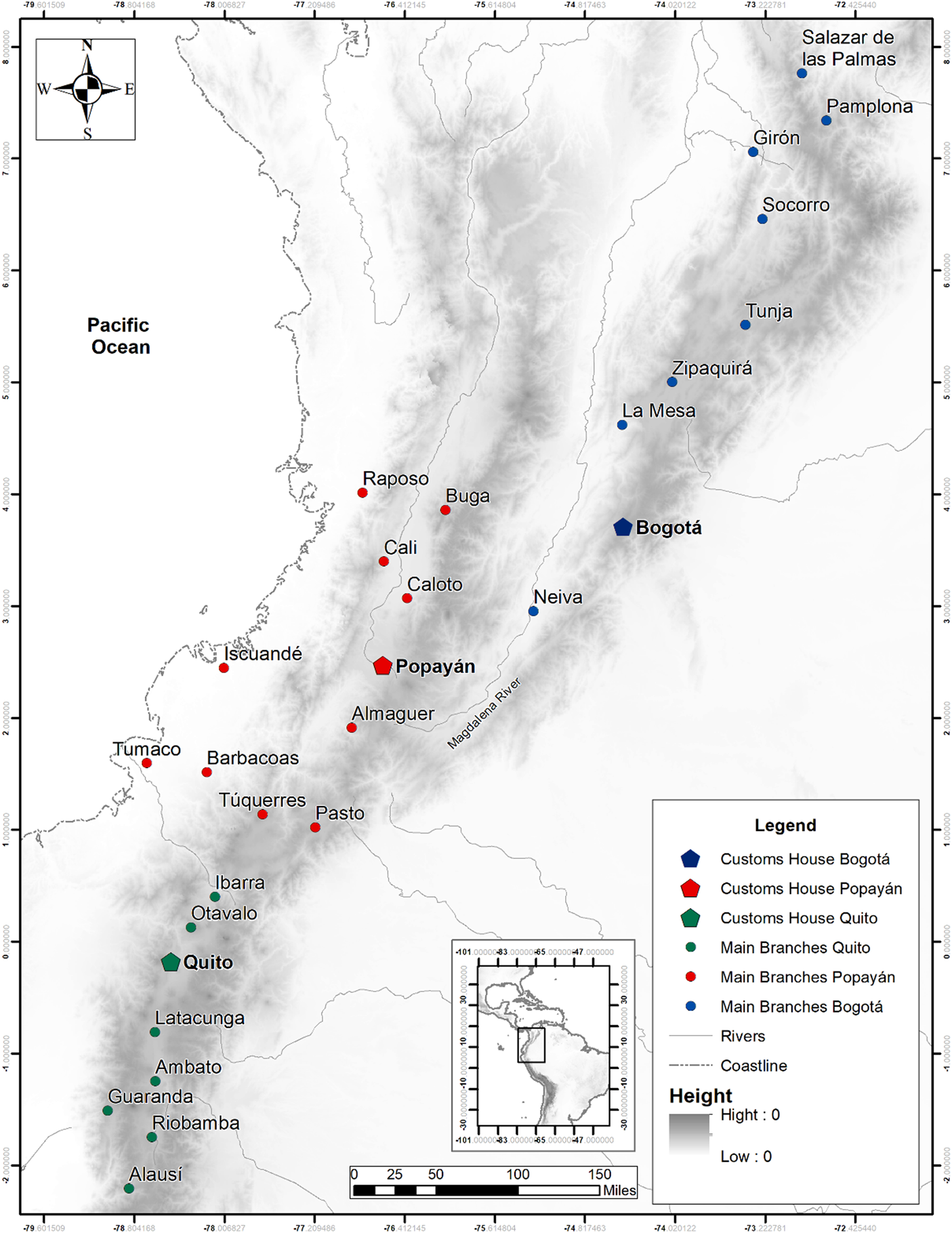

Even though local powers curbed some of the short-term goals of the Bourbon overhaul, the institutional design of the inspectors did slowly take root in the viceroyalty. This process, however, varied across regional settings, given the polycentric connections of the region with the world economy, the extensive network of inland waterways, and the bimetallic structure of the monetary system in some areas. Table 2 shows characteristics of the aduana network across the viceroyalty in the early 1790s (See also Map 1). If compared with the same picture in the late 1770s, the changes are revealing. Over time, direct administration expanded to the chief entrepôts of the viceroyalty and a network of subaltern branches were finally deployed around them. In Quito, Pizarro successfully consolidated subaltern branches in Latacunga, Chimbo, Guaranda, Ambato, Riobamba, and Alausí. In addition, he shored up the reorganization of the customs house in Guayaquil by centralizing the collection of trade taxes and creating subaltern branches across the province.Footnote 65 By 1787, Ibarra, Otavalo, Cuenca, and Loja had been put under direct administration as well.Footnote 66

Table 2 Alcabalas in the Northern Andes, ca 1794: Main Towns and Mechanism of Collection

Source: AGN-A3, Real Hacienda Cuentas, 592-c, 888-c, 1872-c, 1079-c,1172-c, 1307-c, 1565-c, 1890-c, 1234-c, 1539-c, 2826-c, 2798-c, 1654-c, 2260-c, 1892-c, 1279-c, 2491-c; AGN, Anexo 2, Administración de Alcabalas, Cuentas Generales, box 20, folder 1; AGN, Anexo 2-Depósito, box 155, folder 4, and box 73, folder 2, and box 168, folder 1; AGI, Santa Fe, 883-884, 901-902 and 119-1121; AGI, Quito, 426-427.

In New Granada, the process was slower. In 1790, the director of the customs house in Bogotá argued that this sluggish change was “a consequence of the tumults that occurred in 1781.”Footnote 67 In 1787, the administrator of Popayán similarly remarked that “the establishment of the aduana in this city was not effective because of the novelties and revolts in Socorro in 1781.”Footnote 68 Yet by 1792 the branches of the main markets of eastern New Granada were already under the fiscal orbit of Bogotá's aduana. In the early 1800s, further reorganization took place in San Gil, Vélez, Sogamoso, and other thriving markets of the region.Footnote 69 The small markets that dotted the central provinces of the viceroyalty became more and more integrated into the network of customs houses on the eve of colonial collapse.Footnote 70 In Caribbean New Granada, a similar process unfolded, but here the research is scarcer.Footnote 71

In Popayán, the aduanas network was deployed in the 1790s, slowly replacing tax-farming in most of the markets of the region (see Map 1). Popayán's customs house encompassed a heterogeneous set of markets in southwestern New Granada that included the mining belts of the Pacific (Barbacoas, Tumaco, Iscuandé, and Raposo), the agro-mining complexes of the Cauca Valley (Caloto, Buga, and Cali), and the agricultural regions of the southern highlands with a strong indigenous presence (Almaguer, Pasto, and Túquerres).Footnote 72 In the 1800s, direct administration was further expanded toward new mining frontiers such as Micay and Guapi and thriving agro-mining towns such as Quilichao.Footnote 73 Cartago's customs house preserved its independence vis-à-vis Popayán and Bogotá. Given its role in the viceroyalty's east-west trade, the town had had an independent royal treasury since the early stages of colonial rule, and therefore the establishment of the customs house reinforced its autonomy.Footnote 74

Map 1. The Backbone of the Alcabala Network in the Northern Andes, ca 1794

Source: Own elaboration following information in Table 2.

A special case in this new network of subaltern branches was the one deployed in Pamplona, a city that encompassed the so-called “four jurisdictions” that formed the transitional border with the Venezuelan Captaincy: Salazar de Las Palmas, San José de Cúcuta, Rosario de Cúcuta, and San Faustino. This region exported cacao to New Spain and other markets in the Atlantic via Maracaibo, providing Mexican silver for New Granada's merchants. The Pamplona administration was a subaltern of Bogotá's customs house in terms of revenue flows. In institutional terms, however, this branch was a Venezuelan “enclave,” employing some of the tax rates and collection procedures of Maracaibo's customs house. This jurisdictional issue emerged repeatedly after the Maracaibo was declared puerto menor in 1793 and viceregal authorities authorized the importation of European goods from there, Caracas, and Guyana to Pamplona.Footnote 75 This authorization was extended to cover all markets from Bogotá to Pamplona in the early 1800s.Footnote 76 As recent research has shown, by 1805 Maracaibo had become one of the most important entrepôts of European goods for Bogotá's merchants, setting the stage for conflicts between the Andean hubs of trade and the traditional ports of coastal New Granada such as Cartagena.Footnote 77

For reasons that should be addressed in future research, the mining belts of Antioquia and Chocó remained outside the aduanas network. In those areas, sales taxes would be collected by the officials of the royal treasuries until the end of colonial rule. In Antioquia, a plausible hypothesis for this structure is that the alcabala was charged in conjunction with the duties on gold (quintos), with merchants declaring an amount of gold equivalent to the value of the goods imported. This arrangement, known as alcabala presunta, prevented any attempt to restructure sales taxes in the region.Footnote 78 In Chocó, the reason is less clear. The role of the corregidores and the impact of their forced sales (repartimiento de mercancías) on the region's market structure probably conditioned the capacity of the officials to undertake the reform.Footnote 79 The most important Bourbon drive to transform trade in the region was the lifting of the prohibition on navigation along the Atrato River in 1783.Footnote 80 This reform not only enhanced the connection of the region with the Atlantic economy but also compelled the crown to expand the staff of the royal treasury and build proper warehouses in Citará and Nóvita, the two main towns of the province.Footnote 81 Even though the sales taxes of this region were not embedded in the institutional setting of the aduanas, they clearly experienced piecemeal modifications that deserve to be further studied.

The Mechanics of the Alcabalas

As stated in previous sections, each tax category was administered under specific regulations. Let us examine the mechanics of the two main duties. The collection of the sales taxes on goods of Asian and European provenance shifted from a per unit to an ad valorem basis in 1781. In the Northern Andes, such innovation was accepted, despite some initial opposition from import merchants.Footnote 82 However, the practice of paying the tax at customs created protracted disputes. As soon as the new ordinances were enacted, the directors of the customs houses of Bogotá and Popayán started to charge the tax on the full spot price of foreign merchandise. The directors stated that since most of the imports were handled by merchants in Cartagena and other ports on the Atlantic, they were automatically liable to pay a second alcabala in the target market. In other words, the Cartagena importers were to pay the first tax in the port, and the merchants of the interior of the viceroyalty were to pay a second tax, since “the goods have clearly changed ownership.”Footnote 83

The administrators echoed an argument that historians have repeated: that the businessmen from the interior were mere factors of the port merchants.Footnote 84 Yet, the evidence reveals that an increasing number of traders in Bogotá and Popayán imported goods directly from Spain and hired Cartagena merchants to forward their merchandise to the interior.Footnote 85 Thanks to the corporate powers of the trade diputados, interior merchants successfully filed a lawsuit against the measure. They argued that since the goods came from Spain “de su cuenta y riesgo” (at their own risk) and they had to pay both the first alcabala in Cartagena and another in the interior, they should be taxed only on the price difference, not on the full value of the goods. This surcharge was called the mayor aumento. Footnote 86

The viceroy partially settled the dispute in 1785 when he ordered that the alcabala be paid on the full value of the goods only if they were bought in Cartagena. If they were imported directly from Spain, they were also subject to the aumento. Yet, following the advice of the Court of Accounts, the viceroy mandated that the surcharge should not be collected on the price differentials but instead on a fixed 15-percent wedge between the prices of Cartagena and the markets in the interior. This last decision led to a new round of lawsuits and negotiations, and only in 1790 did the method of calculating the surcharge on market prices become a definitive norm. This process was sped up by the fact that Cartagena's centrality waned as the Venezuelan connection and the Santa Marta-Mompox axis became more and more important for Andean importers in the early 1800s.Footnote 87

In Quito, discussions regarding taxes on imports were also prevalent, but the documentation is scarcer. In 1789, an accord among the diputados tangentially stated the need to standardize the method for calculating surcharges on the imports from Cartagena and Guayaquil.Footnote 88 It is not clear, however, if the ongoing procedures for payment of the tax involved price differentials or a fixed rate. Quito's administration did have a separate logbook to measure the aumentos. Unfortunately, only one of these books is preserved, for the years 1796 and 1797, and therefore it is impossible to determine if the practice changed over time.Footnote 89 According to this logbook, the aumento was calculated according to price differentials, for goods coming from both Cartagena and Guayaquil. This practice seemed to have been in place since 1790. In that year, a Quito merchant who imported goods through Cartagena petitioned to pay all the duties in Popayán and Quito since he lacked the liquidity to pay them on spot at Cartagena. Given that he was new to this trade route (carrera), most merchants had refused to lend him capital, even at a high interest rate. Thus, he was to pay both the alcabala de primera venta and the aumento at the two Andean entrepôts.Footnote 90 As compensation, he offered to pay the duties in doubloons rather than silver “so the King will benefit from the premiums at which these coins are traded in this port.” It is not clear if he was authorized to undertake the transaction. Yet he was aware of the difference between the alcabala and the aumento.Footnote 91

The payment of the alcabala on foreign goods gave rise to two additional concerns. First, the customs officials complained that merchants were unwilling to pay the alcabala de reventa despite the fact that most of the merchandise was being sold to retailers inside the city. In Bogotá, a comprehensive plan to tax these transactions stated that “in this city, there is not a clear distinction between the wholesalers and retailers. Both groups varean [to retail or sell the clothes per vara, a unit of length], but only the wholesalers pay the surcharge.”Footnote 92 In Popayán, the administrators stated that taxing the resales was difficult not only because the customs house was understaffed, but also because a portion of retailing was dominated by itinerant merchants who were difficult to track.Footnote 93 The authorities decided that retailing inside the city would be subsumed into other tax categories such as pulperías and tiendas de mercaderes. Merchants, however, would be liable for the reventa if they distributed their merchandise to traders in other provinces. Second, the officials tried several times to reform the conciertos on the grounds that the 18-month window provided the perfect excuse for ultimately avoiding taxation. These attempts elicited lengthy lawsuits that resulted in keeping the structure of three installments of 6 months each, but with a pivotal modification: import merchants had to provide a guarantor to back the entire amount of the debt.Footnote 94

In sum, the task of measuring the streams of European goods in the Northern Andes through records of the alcabalas is filled with significant obstacles. In fact, if taken from the sumarios, the revenues of the customs house do not reflect the real import capacity of the North Andean entrepôts but only the evolving market share of direct importers from Spain and those who depended on merchants in the Atlantic and Pacific ports. If the market share of the former happened to be stronger, the sumarios would clearly underestimate the value of aggregate imports, since most of the tax was charged not on the full value but on the aumento. In the same vein, the sumarios included the revenues gained from taxing the reventas from sales to merchants in other regions. In other words, to reliably establish both the import capacity and the value of re-exports of European goods, a pair-wise analysis must be done between the daily logbooks (libros manuales) and the logbooks of the conciertos.

The alcabala levied on domestic goods was payable on a schedule that was fixed through local negotiations with town and trade councils. Even though the tariffs were supposed to be regularly updated, they remained strikingly stable.Footnote 95 In addition, as this article has noted, some commodities were exempt from taxes in some markets but were liable to taxation in others. It is important to remark that, contrary to a frequent perception of historians, the city councils not only halted increases in the types of commodities liable to the tax but also obtained important fiscal concessions. In the 1800s, after a local interpretation of a royal decree that relieved salted meat and rice from the first alcabala in several Atlantic ports, most of the city councils battled to extend the same exemptions to the interior of the viceroyalty.Footnote 96 Some of them succeeded, and thus both goods were no longer recorded in the accounts of their customs houses.

In the same vein, viceregal authorities saw tax cuts as a mechanism to further promote the booming river trade between the Andean slopes and the Caribbean lowlands. Therefore, they supported lawsuits from the trade councils of Mompox and Honda, the two main inland ports, to reduce and eliminate some duties, despite the opposition of treasury officials. As a consequence, the fiscal burden on the river trade in the viceroyalty became lighter in the 1790s than ever before.Footnote 97 In Antioquia, import merchants achieved tax relief by convincing the courts to allow them to pay the alcabala in silver and not in gold dust. In fiscal terms, the province was to operate as a “land of silver.” Given the movement of the rates of exchange of silver compared to that of gold, and the wedges in the value between gold dust and gold coinage, the real tax rate significantly fell.Footnote 98

The complexity of the negotiations over taxation in the Northern Andes is better understood in light of an examination of nominal and real tariffs. Table 3 provides information on these variables for Quito, Popayán, and Bogotá. The nominal tariffs varied sharply in the three locations. In Bogotá, in comparison to the other two markets, the authorities imposed higher tariffs on cash crops such as cacao, rice, and sugar and its derivatives but charged lower tariffs on livestock and textiles. Curiously, Quito adopted heavier taxes on textiles, its main export commodity. Tariffs on other goods such as hogs were remarkably similar. This sectoral taxation suggests that an analysis of the local discussions about the tariffs would reveal interesting insights into corporate power within different regions. The understanding of nominal rates is also pivotal in undertaking regional, cross-sectional analyses of trade flows. For instance, a raw basic index of tariffs crafted by encompassing the four most important commodities in each market reveals that Bogotá's nominal tariffs were between 20% and 26% higher than in Quito and between 29% and 34% higher than in Popayán. These differences, naturally, affect the way in which fiscal revenues can be harnessed to compare market sizes in the three regions. In other words, if proper adjustments are not made—adjustments that should also include some caveats on the price elasticity of specific goods—the revenues from the alcabalas can lead to overestimates of the market size of Bogotá vis-à-vis Quito and Popayán.

Table 3 Alcabala Rates from Schedules Enacted in Bogotá, Popayán, and Quito, ca. 1792

Source: See sources for Table 2. For price data, see text. * For Bogotá (Sugar), Bogotá (Cacao), Bogotá (Rice), and Bogotá (Garbanzo Beans), averages were different from those of Popayán after performing a Student's T-test and independent samples Mann-Whitney U test with 95% confidence intervals at a significance level of < 0.05.

The analysis of real or effective tariffs is revealing as well, although this is an area in which the literature is scarce. Most studies, in fact, have used the aforos (schedules) as proxies to understand the market value of the commodities recorded in the sales taxes. Very few attempts have been made to establish the gap between those two values.Footnote 99 Julio Djenderedjian and Juan Martirén solidly argue that in regions such as the Río de la Plata interior, in which the aforos were updated regularly, they can be used to derive proxies of price movements and therefore can provide a raw estimate of the value of trade flows.Footnote 100 Jeremy Baskes's analysis of the cochineal trade in Oaxaca has shown that “the customs officials promptly adjusted the avalúos to reflect actual prices.”Footnote 101

In the Northern Andes, the stickiness of the aforos creates issues similar to those faced by historians of other areas of the empire. The last column of Table 3 provides some insights into this regard. Real tax rates shown there were calculated by using monthly prices of key commodities for which data is available in the price indexes of Bogotá and Popayán.Footnote 102 Unfortunately, no such index is available for Quito. Average monthly prices have been calculated for the four years between 1790 and 1794, and a Student T-testEst has been performed to compare tax rates averages between Bogotá and Popayán. The results are straightforward. In Bogotá, domestic goods tended to be taxed more heavily than European imports. As has been shown, the ad valorem rate of the latter remained at 2%, while most of the rates on domestic goods were above that bound. In Popayán, in contrast, real duties on domestic goods were lower, while the capital of the viceroyalty levied heavier rates on them. The two exemptions were textiles and meat, for which the averages are not statistically different. It seems that in both markets indirect tax relief resulted from an upward movement of prices after 1790. The price index soared 30% in Bogotá from 1790 and 1810 and 15% in Popayán during the same period.Footnote 103 Therefore, the real effects of trade taxation diminished during the late colonial period.

What can explain these differences? A definitive answer, again, is beyond the scope of this article. The fact that meat and textiles shared similar burdens in both markets probably indicates the geographical scope of the markets of both goods. Bogotá, Quito, and Popayán competed to attract meat supplies by offering higher prices to producers on the Upper Magdalena River.Footnote 104 In the same vein, textiles from eastern New Granada and Quito competed in Popayán and the Cauca Valley markets.Footnote 105 Any explanation of this phenomenon should also consider the political agenda of the city councils. According to two contemporaries, Francisco Silvestre and Joaquín de Finestrad, the freedoms (libertades) that the towns enjoyed in fiscal terms led to unexpected results. Instead of striving for lower tariffs, some city councils imposed heavy duties, probably to better compete with the produce of nearby towns. Finestrad pointed out that “the cities of the Kingdom taxed goods that were brought from outside their jurisdiction at rates well above [en exceso de] those of Santafé.”Footnote 106 Silvestre, who observed the same phenomenon, recommended the application of a flat ad valorem tax of 2% across the viceroyalty to avoid this heterogeneity that “clearly ruins our trade.”Footnote 107

These insights should shape the procedures used by historians to capture the magnitude and direction of domestic trade flows. One additional comment is in order. Domestic goods were not subject to the alcabala de reventa unless they were sold to a third party in another province. In arguments similar to those made in lawsuits around the alcabala on European imports, merchants claimed that this payment was already subsumed in the ramo de pulperías. This, naturally, created lengthy lawsuits, since merchants would usually move their goods to other towns if the market conditions of their own location were not favorable. Thus, a merchant having paid the tax at customs in market A, was not forced to pay it at market B. Nonetheless, given the heterogeneity of tariffs and the drive to increase revenues, officials several times attempted either to charge the reventa on these transactions, or to charge an aumento on the price differentials of both markets.Footnote 108 However, traders were successful in curbing both attempts. This negotiation is well reflected in records of accounting practices. The libros manuales recorded not only the introduction of goods but also, in side notes, informed if they were re-exported with a new outbound waybill. Here, again, the Northern Andes diverged from the patterns in operation in other regions of the Empire.

Broad Trends: The Sumarios Generales

The former sections have provided some cautionary outlines regarding the use of the annual summaries of the customs houses to grasp trade flows. A burgeoning recent literature has set out to go beyond these accounts to understand the mechanics of taxation across the Spanish Empire.Footnote 109 However, even the leading scholars of this revisionist wave have recognized that the study of the annual summaries is a provisional step for establishing robust pictures of fiscal revenues over time. In fact, in the very process of testing these figures, scholars have attained important insights into the region's economic history. That is why, perhaps, the monumental treasury-based studies of Herbert Klein, John TePaske, and Álvaro Jara are still useful despite their ubiquitous use of the annual summaries.Footnote 110 Therefore, both cross-sectional and time-series analyses of the summaries of sales taxes revenues in the three main North Andean trade hubs can provide some preliminary hypotheses on the market structure of the region. Future research should test these hypotheses once the customs records are properly deconstructed. This exercise, moreover, will provide important insights into the comparative development of the Northern Andes in the context of the Spanish Empire.

Figures 1 through 3 present the total revenues from sales taxes in the three entrepôts, as measured through the annual summaries. OLS time regressions have been estimated to permit a look at the rates at which these revenues performed per decade. The results are revealing. In Bogotá, revenues doubled, from roughly 53,000 silver pesos annually in the years 1782 to 1785, to 107,000 silver pesos in the years 1800 to 1803. In Popayán and Quito, revenues grew more modestly, from roughly 18,000 and 17,000 silver pesos respectively in 1782 to 1785, to 28,000 and 24,000 silver pesos in 1801 to 1803. By 1800, Bogotá had become the most important node in terms of the agglomeration of the revenues from trade taxes.

Figure 1 Total Revenue of Bogotá's Alcabalas in Nominal Silver Pesos According to the Sumarios Generales

Source: AGI, Santa Fe, 805-806; AGN-A3, Real Hacienda Cuentas, 1932-c, 2123-c, 2011-c, 1856-c, 1784-c,1892-c, 2133-c, 2538-c, 1583-c,1726-c, 1753-c, 2761-c, 2863-c; AGN-A2, Administración de Alcabalas, Cuentas de Cargo y Data, box 8, folders 1-2.

Figure 2 Total Revenue of Popayán's Alcabalas in Nominal Silver Pesos According to the Sumarios Generales

Source: AGI, Quito, 519-521; AGN-A3, Real Hacienda Cuentas, 1934-c, 522-c, 599-c, 591-c, 486-c, 552-c, 1968-c, 1683-c, 2096-c, 1291-c, 1654-c, 467-c, 598-c, 1685-c, 492-c, 563-c, 494-c, 456-c; AGN-A2, Administración de Alcabalas, Cuentas de Cargo y Data, box 17, file 3; AGN-A2D, box 19, files 2-6.

Figure 3 Total Revenue of Quito's Alcabalas in Nominal Silver Pesos According to the Sumarios Generales

Source: AGI, Quito, 432-434; ANE, Alcabalas, box 26, book 1; box 27, books 2, 3, 5, 7; box 28, books 1, 4, 5. The revenue from the subaltern branches before 1790 has been discounted; after that year, these revenues were submitted directly to the royal treasury.

Figure 4 provides the results of the OLS regressions that, as has been mentioned, can be interpreted as the rates at which the revenues grew per decade. In the first decade after the reforms of the 1780s, revenues soared in Bogotá, but they grew at slower rates in the 1790s and 1800s. In Quito and Popayán, revenues grew at a significant pace during the 1780s, but in the following two decades, the slope of the linear regressions shows that they became stagnant, and even negative. In other words, by the eve of the collapse of colonial rule the incomes from trade taxes had reached a plateau. These North Andean patterns are not unique in the context of the Spanish Empire. In New Spain, fiscal revenues from trade taxes soared after the widespread expansion of the direct administration in the 1770s, plateauing until 1810.Footnote 111 For the Northern Andes, the positive slopes of the linear regressions during the 1780s may reflect the short-term increase in returns from the institutional and infrastructural transformation that followed the reforms, while the subsequent deceleration may reflect diminishing returns in tax collection, the effect of tax exemptions, and a downturn in trade flows.Footnote 112

As stated above, the region's trade and town councils achieved significant tax cuts in the late 1790s, while the literature has documented the contraction of mining and its linkages on the eve of colonial collapse.Footnote 113 More data are needed to fully explain the trends distilled here. However, these numbers are a reminder that the traditional view of the Bourbon period as a successful, linear drive to exert fiscal pressures should be taken with a grain of salt.

An analysis of the role of each tax category in the total revenue of the aduanas helps us to form additional hypotheses. Tables 4, 5, and 6 depict the evolving role of each ramo in the streams of revenue of the North Andean entrepôts. The data have been broken down into three trienniums that reflect the changing conditions of markets in the context of the Atlantic wars and environmental shocks.Footnote 114 The first triennium depicts the structure of the late colonial economy during a period without external shocks in terms of wars or bad harvests. The 1798-1800 period captures the first shock associated with the Anglo-Spanish war and the adoption of the comercio con neutrales. Finally, the last triennium portrays the situation during the outbreak of war with England and important environmental shocks that caused changes in harvest cycles, as documented by environmental historians.

Table 4 The Evolving Role of Tax Categories, Shown as Percentages of the Total Alcabala Revenue in Bogotá

Source: This table uses the same sources as Table 1.

Table 5 The Evolving Role of the Tax Categories as a Percentage of the Total Alcabala Revenue in Popayán

Source: This table uses the same sources as Figure 2.

Table 6 The Evolving Role of the Tax Categories as a Percentage of the Total Alcabala Revenue in Quito

Source: This table uses the same sources as Figure 3.

In Bogotá, as Edwin Muñoz has shown in a rigorous study, the revenues from the subaltern branches and the tax farmers at the local level determined the overall financial performance of the customs house.Footnote 115 These numbers suggest that the network built by the authorities around Bogotá was fiscally successful as far as sales taxes are concerned. Yet, it is worth pointing out the survival of tax farmers, despite the crusade for the expansion of direct administration. As stated above, tax farmers were retained in those small markets in which direct administration was not regarded as profitable. The aggregate size of these small sources of revenue reflects, therefore, the importance of small markets across eastern New Granada.Footnote 116 To analyze the fiscal importance of Bogotá as an entrepôt, the revenues from the subaltern branches and the farmers should be discounted. Once this adjustment is carried out, a multiple linear regression identifies the impact of specific ramos on the overall trend of the aduana revenues. The movement of the taxes on European goods explains up to 95% of the movement of total revenues. The coefficient that captures the same measure for domestic goods is low and not statistically significant. This pattern is partially explained by the fact that the overall trend of the revenues from domestic goods was less volatile than the revenues from taxing foreign wares.

As for Quito, there is no need to discount the revenues from the subaltern branches, since they were deposited directly in the royal treasury after 1790. However, if the data on these revenues as provided by Fernández is used to create a simple counterfactual, the subaltern branches would have accounted for 25% to 30% of the global income of Quito's administration.Footnote 117 In other words, Quito's dependence on the revenues from the subaltern branches was not as strong as in Bogotá. Popayán followed an intermediate pattern. In ways similar to the viceregal capital, the revenues drawn from subaltern branches were pivotal. Nonetheless, most of these streams came from markets in which direct administration was fully operating. In fact, after roughly 1793, tax farming disappeared from Popayán's records.

This does not mean that this practice had waned in the region. Most tax farmers at the local level simply deposited their surpluses in Popayán's subalterns. Once the revenues from other branches are discounted, it is possible through multiple linear regression to identify those tax categories that exerted a greater impact on the variation of total revenues. In Quito and Popayán, taxes on European goods accounted for 88% and 82% of the movement of total revenues, respectively. In other words, the revenues of the customs houses of the Northern Andes were highly sensitive to the movement of international trade.

These trends reveal even more if they are put into a broader, comparative context. Grosso and Garavaglia have provided a breakdown of the revenues from the ramos that taxed European, Asian, and domestic goods in the main administrations and branches of New Spain's customs houses.Footnote 118 According to their data, the average share of European goods in total revenues of the alcabalas stood at 35.5% in 1796, including Mexico City. This average concealed regional variations. In Durango, taxes on European goods accounted for 46% of the alcabalas, while in Valladolid they accounted for less than 20%.Footnote 119 In the South Central Andes, the role of the revenues from European goods tended to be higher in Potosí (38-45%) and Cerro de Pasco (44-56%) but lower in Oruro (5-20%).Footnote 120 In the Northern Andes, these patterns differed from region to region. The share of the levies on European goods in Bogotá and Popayán tended to be around the same range as New Spain's average. In Quito, on the other hand, these shares tended to be even higher than those of Potosí and Cerro de Pasco.

What variables explain this pattern? The lack of serial data on prices of imports precludes the provision of any definitive answer. Some scholars have stated that prices of imports in Quito tended to be higher than in Popayán and Bogotá due to location and distributional patterns. Likewise, Bogotá taxed domestic goods more heavily than European goods, thereby affecting the relative importance of each one in the total income of the aduanas.Footnote 121

Most scholars have used the breakdown of customs revenues to state that, in aggregate terms, most of the goods transacted in the region were produced inside the economic spaces that integrated the empire. Considerable discussion has ensued on the nature and scope of this statement.Footnote 122 In absolute terms, the impact of international trade on fiscal flows was overshadowed by the importance of the non-tradable sector. Yet, as the regressions performed above have shown, by the late colonial period, the sensitivity of fiscal revenues vis-à-vis European and Asian imports is beyond doubt. Given the fierce competition among the different circuits of trade to supply goods of global provenance to the Andean interior during the Atlantic wars, this sensitivity helps to explain why the dispute over customs revenue became a new element of the political conflict among merchants and treasurers of different regions on the eve of colonial collapse.Footnote 123

Final Remarks

The article has delivered a broad examination of the mechanics of sales taxes in the Northern Andes during Bourbon rule. By advocating a careful examination of the accounting, institutional, and fiscal practices of the customs houses, it has provided an extensive exploration of the ways in which the customs records can be harnessed to study the scope and nature of Bourbon reforms, to measure trade flows, and to emphasize the effect of local negotiations and jurisdictional fragmentation on local rates and revenue collection. Although such an exploration is hardly a novel undertaking, the evidence studied here provides new inputs to expand the field in at least three broad ways.

First, the evidence confirms that a compromise between reform and tradition shaped the scope of fiscal innovations. The alcabala differed from region to region, and tax rates, liabilities, and exemptions were adjusted locally. The authorities were aware of this pattern, and while they tried to create uniform taxation, they also yielded to “adapt the rules to local circumstances.” The mechanisms employed by taxpayers to negotiate fiscal reform suggest, however, that corporate power proved resilient, with city councils, trade councils, and other bodies using litigation and ad hoc methods to achieve important, yet little-explored fiscal concessions, such as the right to negotiate the schedule of the duties that fell upon domestic trade. The extent to which this structure favored or hampered economic growth is a matter of contention among specialists. In particular, the political use of local tariffs by city councils is a topic that deserves further attention. Future research should focus on the mechanics of specific ramos, not only to craft time series but also to identify the sectoral impact of taxation across colonial society.

Second, the heterogeneous nature of trade taxes in the Northern Andes demands caution in any attempt to undertake cross-section and time series analyses of the annual summaries. Even though these accounts are useful in fiscal terms, they are not a good proxy to analyze the structure and size of North Andean markets. Therefore, a combined analysis of the different logbooks of the customs house is needed to distill hard data on trade flows. This approach will allow historians to establish whether the entries of some tax categories were measuring re-exports, imports, or current or due debts, providing some insights into the size of the aggregate market and the role of some towns as distribution centers for local and foreign merchandise.

This article argues that the data extracted from the customs house provide a lower bound for the magnitude of regional trade flows. This lower bound was a function of the size of the population exempted from the tax (mainly Indigenous peoples), the market share of specific goods not liable to the alcabala, regional tax rates, price elasticities, and the technology of tax collection in each customs house. Some of these variables are not directly observable in the records. However, the robustness of the data provides solid ground for understanding some of these patterns. For instance, real tax rates were higher in Bogotá than in Quito and Popayán. Other things being equal, a cross-sectional analysis of the market sizes of the three entrepôts can be biased in favor of Bogotá if adjustments are not properly carried out.

Finally, caution should be exercised in using the fiscal capacity of the Spanish treasuries as a proxy of the economic significance of the Northern Andes. The analysis of sales taxes suggests that the region enjoyed broader fiscal prerogatives, with some sectors getting tax discounts during the very moment in which the Bourbon drive for revenues was at its peak. While former studies have interpreted this lack of taxation as a symptom of a lack of economic activity, this article has shown how the specific endowments of the region reinforced negotiations and left several streams of trade untaxed. In this vein, prevalent views that depict the Bourbon effort at increasing fiscal revenues as a successful, linear process should be revisited. The analysis of the sumarios generales suggests that the proceeds of customs houses flowed well in the 1780s and 1790s but plateaued or declined in the early 1800s. It seems that these trends reflect a contraction in some branches of trade, diminishing returns in tax collection, and, surprisingly, a drive towards lower real rates in trade taxes. The polycentric connections of the Northern Andes with the global economy, the bimetallic nature of its monetary structure, the fiscal competition among its city councils, and the importance of the region's inland waterways, conspired to create a fiscal structure the understanding of which provides new venues to study the history of the Bourbon reforms in the Americas.