Introduction

In a world where particular groups feel increasingly isolated, understanding how this can be reduced through social interventions that create the opportunity for emotional togetherness is much needed (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012; Jose and Cherayi, Reference Jose and Cherayi2016; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Jepson and Stadler2018; Massey et al., Reference Massey, Edwards and Musikanski2021). Socially centred creative art experiences appear to be ideal contexts in which to create such emotional togetherness and encourage a stronger and lasting sense of belonging for older people (Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2007; Moody and Phinney, Reference Moody and Phinney2012; Cantu and Fleuriet, Reference Cantu and Fleuriet2018; Sutherland et al., Reference Sutherland, Dunkle, Pace, Kennedy and Baldwin2019). Previous research, however, tends to focus on the immediate impact of the experience, sometimes with a focus on the emotional (Price and Tinker, Reference Price and Tinker2014; Bastiaansen et al., Reference Bastiaansen, Lub, Mitas, Jung, Ascenção, Han and Strijbosch2019), but as yet there is little that considers the effects of repeated emotional engagement during collective creative experiences (Chapin Stephenson, Reference Chapin Stephenson2013; Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013; Noice et al., 2013). This attunes with Gallistl's (in press) recent call to consider creativity in older adults as a collective and social activity rather than merely an individual process. The ‘value’ of creativity, discussed by Gallistl (in press), leads to a consideration of the sense of one's own value and therefore to the concept of self-worth. Self-worth has been found to decline in older age, leading to negativity and a withdrawal from society (Ravary et al., Reference Ravary, Stewart and Baldwin2020). Self-worth is therefore inextricably linked to feelings of belonging or of loneliness; it can potentially be enhanced through creative activity (Fisher and Specht, Reference Fisher and Specht1999; Moody and Phinney, Reference Moody and Phinney2012), and is therefore the focus of our study.

The increase in loneliness presents major challenges to modern society (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012; Age UK, 2018). These concerns are particularly acute in the case of rural-living adults where there is greater risk of social isolation (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012; Davidson and Rossall, Reference Davidson and Rossall2014; Hennessy and Means, Reference Hennessy, Means and Walker2018; Stadler et al., Reference Stadler, Jepson, Wood, Page and Connell2020), which is exacerbated by reduced transport, distances to social services and family member migration. Furthermore, the voices of older women remain underrepresented in much academic research, including the leisure literature (Small, Reference Small2003; Henderson and Gibson, Reference Henderson and Gibson2013; Wood and Dashper, Reference Wood and Dashper2021). Notable exceptions to this and the inspirations for our work are the conceptualisation of older women's art and craft participation by Liddle et al. (Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013), and Maidment and Macfarlane's (Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2009, Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2011) studies of older women's experiences in craft groups. Liddle et al. (Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013: 337) conclude that ‘participation in art and craft activities [can create] a symbolic wholeness, where it is possible to complete items, help others, be valued and enjoy the moment’. Maidment and Macfarlane (Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2009: 23) also highlight the meaningfulness in completing an individual artefact and the importance of the ‘process of belonging and contributing to the craft group [as] a major source of personal support for these older women, where reciprocity, friendship, learning and empowerment [are] derived from being part of the collective’. It is the social process through which this happens that we explore in our study.

The gendered experiences of ageing have long been recognised (Carter and Everitt, Reference Carter and Everitt1998) and more recently gender has been related to differing manifestations of loneliness (Dahlberg et al., Reference Dahlberg, Andersson, McKee and Lennartsson2015; Rokach, Reference Rokach2018; Wood and Dashper, Reference Wood and Dashper2021). The social networks of women over 70 years often become depleted over time and therefore the forming of new relationships through group activities becomes of greater importance (Russell, Reference Russell1987; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Ashton-Shaeffer, Green and Autry2003; Foster and Walker, Reference Foster and Walker2013). Older people's behaviour, in terms of likelihood of engaging in such social experiences and the frequency of them, has also been found to be positively linked to gender (female) (Losada et al., Reference Losada, Alén, Domínguez and Nicolau2016) and significantly correlated with feelings of belonging and negative affect (Massey et al., Reference Massey, Edwards and Musikanski2021).

Taking part in arts, cultural and community activities enables older women to connect with others and create social networks (Moody and Phinney, Reference Moody and Phinney2012), increasing their confidence and leading to a better quality of life (Greaves and Farbus, Reference Greaves and Farbus2006; Maidment and Macfarlane, Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2009; O'Shea and Leime, Reference O'Shea and Leime2012; Carnwath and Brown, Reference Carnwath and Brown2014; Bennington et al., Reference Bennington, Backos, Harrison, Reader and Carolan2016; Joseph and Southcott, Reference Joseph and Southcott2019). Indeed, Cutler (Reference Cutler2012), in the Baring Foundation report into the arts and loneliness, concludes that such activities ‘exemplify the “five ways to well-being”: connect; be active; keep learning, take notice and give’. Despite these findings, there continues to be a scarcity of research based on robust evidence, and very little that explores the processes by which these benefits occur in a social creative arts setting (Noice et al., Reference Noice, Noice and Kramer2014; Price and Tinker, Reference Price and Tinker2014).

We propose that a combination of new experiences outside the home, with some element of creativity and challenge, and a socially stimulating environment will enhance belonging and self-worth for older women, but that this will be dependent upon the development of emotional togetherness. We also contend that it is unlikely that such benefits can be achieved through one-off activities but require repeated ‘interventions’ centred around peer social interactions (Carter and Everitt, Reference Carter and Everitt1998; Jenkins and Mostafa, Reference Jenkins and Mostafa2015; Torres, Reference Torres2016). Our study explores this through rural group art and craft experiences undertaken on a regular basis over an extended time.

As our starting point, we assume that the desire to share such experiences with others and have the same emotional reaction to them to be an innate part of human nature (Woosnam, Reference Woosnam2011; Krueger, Reference Krueger2015; Rimé, Reference Rimé and Holyst2017). As social beings we seek out the company of others to reaffirm our place in the world, in terms of reflected identity, and to mitigate our existential isolation (Pinel et al., Reference Pinel, Long, Landau, Alexander and Pyszczynski2006). This need to be with others to feel like ourselves creates a related need – to feel that we are experiencing the same emotional reaction as others. It is this emotional group identity which appears to have the longest lasting effect and therefore the potential to create the most benefit for participants’ wellbeing (Páez et al., Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Porat, Yarkoney, Reifen Tagar, Kimel, Saguy and Halperin2017). Studies have already shown the benefits of mirroring and physical synchrony for wellbeing and cognitive performance in older people (Keisari et al., Reference Keisari, Feniger-Schaal, Palgi, Golland, Gesser-Edelsburg and Ben-David2020) but few have studied emotional synchrony in this age group.

We, therefore, take our theoretical premise from the concept of perceived emotional synchrony of Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015). We build upon their quantitative studies by taking a qualitative approach to explaining the manifestation of perceived emotional synchrony in social creative activities and the role of this in developing feelings of belonging and self-worth. Our aim is to use perceived emotional synchrony as the theoretical basis for understanding the process through which regular social creative activities can enhance a sense of belonging and self-worth in older rural-living women.

Emotional synchrony

Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1912) considered the effects of collective gatherings, philosophising that sharing heightened emotions with others creates positive changes post-experience. He believed that this results in an increase in confidence and a renewed belief in social institutions. Although neglected for close to a century, collective emotions have now become a major topic within both psychology and sociology (e.g. Collins, Reference Collins, Scherer and Ekman1984; von Scheve and Ismer, Reference von Scheve and Ismer2013; von Scheve and Salmela, Reference von Scheve and Salmela2014; Páez et al., Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015).

However, there is an ongoing debate around the very existence of collective emotions, e.g. Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015) would argue that emotions can only ever be felt individually, and that sharing is merely illusory. Others suggest, similarly to Durkheim's emotional contagion, that emotions are ‘caught’ from others through a variety of processes (Hatfield et al., Reference Hatfield, Cacioppo and Rapson1993; Murray and Crummett, Reference Murray and Crummett2010). This spread of emotions suggests that a collectivity exists in some form and that it can be created. However, there is also growing evidence that we merely perceive others to be feeling as we are in many situations and that, quite often, this reflects a desired rather than actual emotional collective (Schmid, Reference Schmid2009; Salmela, Reference Salmela2012). Whatever the process of collective emotion development, it appears to be driven by a strong need to believe that we feel the same as those around us (Rimé, Reference Rimé2007; Salmela, Reference Salmela2012; Wood and Kenyon, Reference Wood and Kenyon2018; Wood, Reference Wood2020) and that the benefit of this possible fiction is a stronger sense of belonging (Hammond, Reference Hammond, Stets and Turner2006; Pinel et al., Reference Pinel, Long, Landau, Alexander and Pyszczynski2006).

In this paper, we take the stance that emotions are individually experienced, but highly influenced by others and that synchrony, whether perceived or real, serves an important social function (Zumeta et al., Reference Zumeta, Oriol, Telletxea, Amutio and Basabe2016). Any social activity has the propensity to create environments where emotional synchrony can flourish and, in turn, this can generate a greater sense of belonging and a stronger group identity. Understanding the process through which this occurs is important within many experiences where groups gather and lasting connections are made with like-minded others (Carter and Everitt, Reference Carter and Everitt1998; Jenkins and Mostafa, Reference Jenkins and Mostafa2015).

Perceived emotional synchrony therefore is conceptually interesting in the case of smaller group social activities where a feeling of oneness is likely to have the most beneficial effect. Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015: 714) articulate that this value occurs as ‘collective behaviours help to infuse emotional energy by enhancing positive affect and emotions, including feelings related to social categories such as collective self-esteem’. They further explain that this ‘psychosocial well-being rests on the intensification of socially shared emotions and on the strengthening of perceived similarity, unity … with the group [which], in turn, reinforces positive social beliefs and social integration’ (Páez et al., Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015: 727). Recently, Włodarczyk et al. (Reference Włodarczyk, Zumeta, Pizarro, Bouchat, Hatibovic, Basabe and Rimé2020: 11) provide further evidence that ‘emotional synchronization in collective gatherings is conducive to strong forms of social identification, particularly the overlapping of the individual with the collective self’. Therefore, perceived emotional synchrony plays an important role in group collective efficacy (Zumeta et al., Reference Zumeta, Oriol, Telletxea, Amutio and Basabe2016) and, when the synchrony is high, reinforces fusion of identity, or the overlapping of self and others (Páez et al., Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015). In its simplest form this relates to the desire for social activities and the resulting wellbeing effects of these (Ross, Reference Ross2005).

Gendron and Barrett (Reference Gendron and Barrett2018) present a convincing case for the co-construction rather than synchronisation of emotion. They argue that this is created by a constant interplay of perceived emotion in others and emotion regulation in ourselves. They conclude that this is an iterative process largely driven by the language used in a group. The group narrative and its role in emotional synchrony underpin our methodology both in observing this in a naturalistic setting and in group discussions held outside the activity. Within our methods we have also incorporated Carter and Everitt's (Reference Carter and Everitt1998) findings that conversation and friendship are key in developing social activities which see the participants as active subjects rather than passive objects of practice.

Our research begins with the assumption that getting out of the house, being with others and participating in an activity, in our study arts and craft sessions, will allow for self-expression through creativity. The social activity of being creative together provides a shared purpose through which a sense of belonging can develop (Cantu and Fleuriet, Reference Cantu and Fleuriet2018; Gallistl, Reference Gallistlin press). This happens through challenge and achievement and, most importantly perhaps, by stimulating emotional synchrony within the group that lasts beyond the experience. The shared creative activity generates emotional responses and thus acts as a catalyst for social engagement, the affirmation of others, and for self-belief through a sense of feeling valued and of belonging (Ni et al., Reference Ni, Tein, Zhang, Zhen, Huang, Huang and Mei2020). Borrowing from the study by Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015), we therefore explore whether perceived emotional synchrony is co-constructed during a social creative activity and what the beneficial outcomes of this are. The benefits are expected to accrue through a process of identity fusion, social integration, positive affect, empowerment and shared symbols (social beliefs).

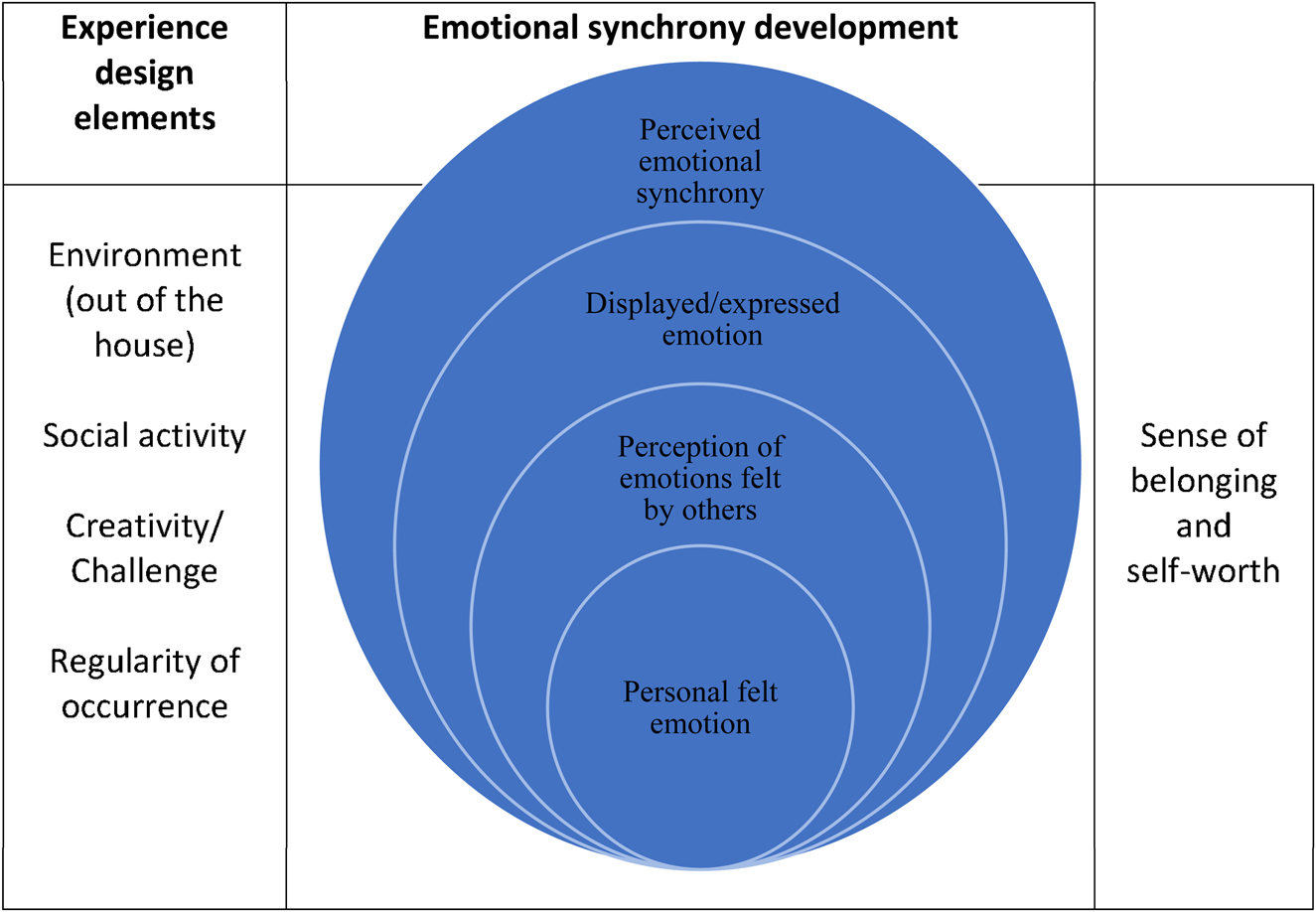

We have adapted this into our own theoretical framework (see Figure 1). The intention is to extend the work of Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015) by considering the effects beyond a one-off experience and exploring the cumulative impact of social activity and creative participation on perceived emotional synchrony, and the ensuing benefits of this. Our model begins with identified enablers of perceived emotional synchrony relating to the design of the art and craft group experience. These are experiential components, derived from Gentile et al. (Reference Gentile, Spiller and Noci2007) and the person–environment process (Chaudhurya and Oswald, Reference Chaudhury and Oswald2019), thought to have the potential to create the ‘effects’ discussed by Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015). Central to the proposed framework is the expanding emotional engagement resulting in perceived emotional synchrony. Finally, the framework recognises that perceived emotional synchrony is the conduit between the experience and the wellbeing outcomes.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework.

Sample and methods

The two geographic regions in the United Kingdom (UK) for our study were identified by the Age UK loneliness heat map as being areas where there was a high risk of loneliness in older populations (Rossall et al., Reference Rossall, Iparraguirre and Davidson2015). The regions differed slightly in size with a total of 32 participants in the North of England and 30 participants in the South of England. We selected only women to address the gender bias in much academic research, and in recognition of the gendered experience of ageing and loneliness. The majority of participants were from lower socio-economic groups with limited resources for travel and leisure, reflecting some of the social constraints identified by Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Ashton-Shaeffer, Green and Autry2003).

Participants were recruited from the existing attendees of weekly Age UK sessions (known as Living Well Mondays and ‘10 till 2 clubs’). Prior to the research attendees in the Living Well Mondays and the ‘10 till 2 clubs’ normally took part in more individualised activities such as bingo, dominoes, quizzes or completing jigsaws. The research team presented an overview of the research process and purpose and invited anyone interested to take part. Not all members of the groups took part in the research although the majority joined in the activities. Sixty-two women (out of a possible 75) agreed to be part of the research. Reasons for not participating included health (e.g. hard of hearing so did not feel comfortable in the discussion), and preferring just to spend time with their friends chatting. The groups contained some existing friendships but most did not know each other and/or were relatively new members, allowing us to observe how existing friendships deepened and new friendships developed.

The social creative activities varied between groups, and included self-portraits using iPads, flower arranging, choral singing, origami, canvas bag making, glass jar and terracotta plant pot painting, and 3D wooden model making. Participants were already attending various types of venues (community centres, village halls, sheltered housing/retirement housing, assisted living housing) where the age-related charity-run sessions were based. Although the participants were already members of the weekly groups, they had not undertaken art and craft activities there before. These new activities were developed and facilitated by our artist partner organisations and took place weekly over several months, for groups of between 10 and 20, at two locations in the North of England and four locations in the South.

Members of the research team attended all sessions and invited groups of three or four women at a time to take part in additional weekly discussions. Each smaller group attended these post-activity discussions for three weeks. The weekly group discussions formed our core method and were complemented by the use of photography and participant observation during the creative sessions. The activity facilitator for each session wore an autographer digital camera device set to take photographs automatically.

As researchers we participated in the activities and made observational notes which included classifying the type of activity, the level of creativity, degree of independence and difficulty level of the activity. Observational notes were also taken in respect of the physical environment of each session (description of the setting, role of the facilitator, mode of instruction), conversations that participants had (topics, stories, engagement), as well as displayed emotions (with a focus upon facial expressions: smiles, frowns or laughter).

The narrative group discussions consisted of one researcher and three or four participants. These took place the week after the activity, each week for three weeks, with each discussion lasting approximately 60 minutes. Participants were given visual artefacts (often the items made the previous week) or shown photographs as memory cues and asked to talk to each other about their past and present lives and the previous week's activity. The researcher maintained a largely observational role with the participants, determining the flow and content of the discussions. This method was adopted as a result of Hirst and Echteroff's (Reference Hirst and Echterhoff2008) findings that collaborative conversations with others result in remembering more than individual recall and to enable a situation where emotional synchrony might further emerge (see also Carter and Everitt, Reference Carter and Everitt1998; Gendron and Barrett, Reference Gendron and Barrett2018). Over the three-week period, the women developed a sense of trust and rapport with each other as well as with the researcher, which allowed the discussions to flow naturally, providing privileged insights into their thoughts and feelings.

Data analysis

Data collection over an 18-month period resulted in rich narratives from 62 older women which included broader reflections on their lives and an open exploration of their feelings about the participatory art and craft sessions. After transcription, interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) of the discussions and observational notes was undertaken. In using IPA we have attempted to understand each woman's lived experience of the art sessions and how these relate to their past and present lives, their feelings of belonging and of self-worth. As IPA is idiographic in its commitment to examining the detailed experience of each case in turn, prior to the move to more general claims (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flowers and Larkin2009), we have attempted to keep the narratives intact and to draw out individual cases before concluding on the whole. Our sample size is large for this type of study and therefore we have had to be selective in the excerpts presented in this article. The quotations used therefore represent the individual and have been selected to also illustrate findings which were seen in other cases.

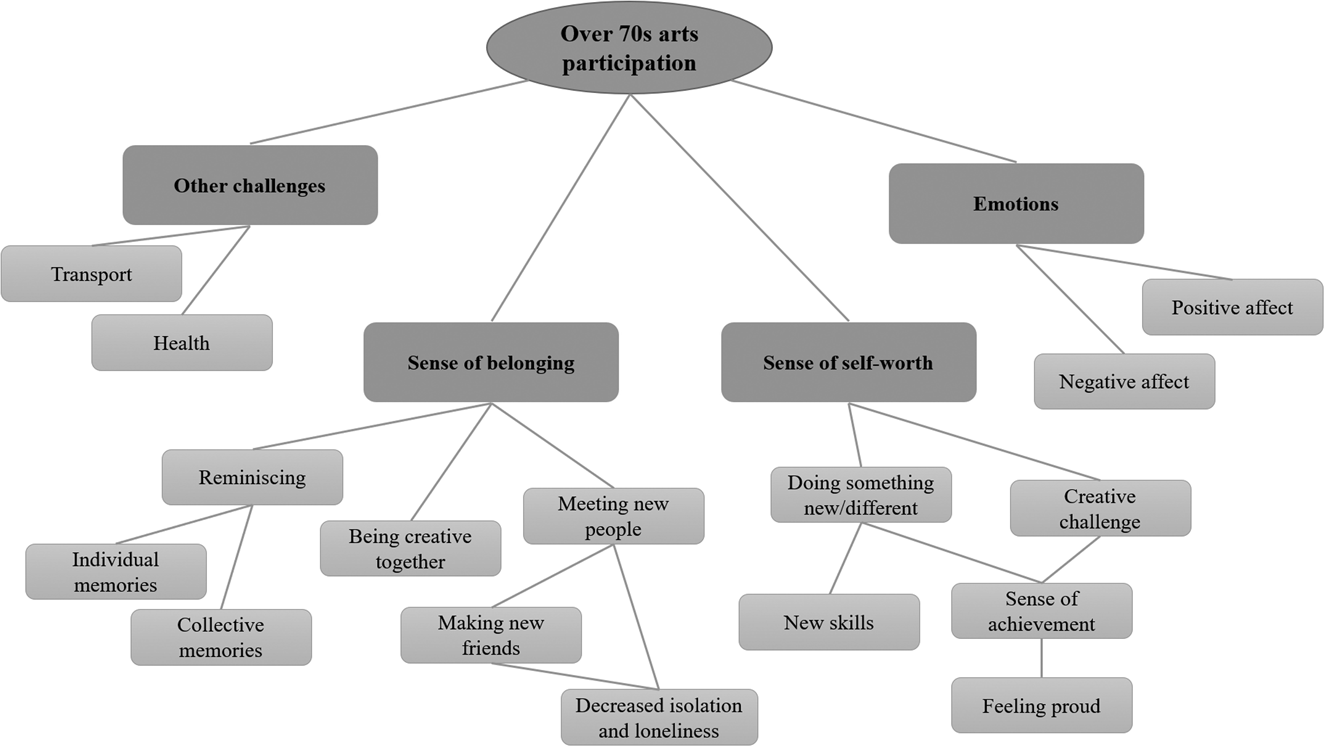

Due to the sample size we enhanced our analysis using NVivo version 11.4.3 (QSR International, Melbourne). The three researchers independently worked through the transcripts and researcher notes to identify key words and phrases, and labelled these with appropriate codes. After comparison and discussion, 20 codes were identified, initially with no hierarchy specified – all codes were treated as equally important. The codes ‘positive affect’ and ‘negative affect’ were then further analysed (through matrix coding and comparison diagrams) relating to ‘being creative together’ and ‘creative challenge’; ‘doing something new/different’ (new skills, feeling proud, sense of achievement); and ‘meeting new people’, ‘making new friends’ and ‘decreased isolation and loneliness’. This identified whether individually felt and expressed emotions changed over time, as well as whether participants perceived emotional synchrony during the social creative activity and/or when reflecting upon it afterwards. It also allowed reducing all initial codes down to the two main concepts: ‘sense of belonging’ and ‘sense of self-worth’, with all other elements contributing to these through the experience of ‘positive affect’ (see Figure 2). In a final step, codes and emerging themes were realigned with existing literature, such as the original perceived emotional synchrony model by Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015), in order to develop a more critical discussion (Bazeley, Reference Bazeley2007).

Figure 2. NVivo coding structure.

Findings

As presented in Figure 1, we discuss two main wellbeing outcomes, creating an enhanced sense of belonging and developing a sense of self-worth. These are explored by focusing on different experience enablers and the process of emotional synchrony development for each. In line with an IPA approach, we focus on two group case studies to represent these findings and provide more specific examples. These are presented as verbatim conversation and individual quotes to maintain the voice of each participant and the context of their comments, alongside researcher observation notes. The selected case study groups are one from the South (Participants 1–6) and one from the North (Participants 7–12).

Sense of belonging

Developing a sense of belonging was identified as a key wellbeing outcome for women over 70 that could be achieved through social creative activities. The experience design elements of the environment (being out of the house) and the co-presence of others were thereby important elements enabling the development of a sense of belonging. Participants 1 and 2, for example, discussed the importance of regularly having a day out and enjoying the company of others, whom they have become friends with over the course of the three weeks:

Participant 1: Well, I live alone and I can't see nothing. I get so bored indoors. I get bored because I can't see the television properly. I can't read, I can't knit and I can't sew and I find it boring. I have the television on but I tend to look sideways at it and listen. But when I'm at home, I am bored. The days are long because there's nobody even to talk to … I love getting out.

Participant 2: Also getting to know people and talking to them.

Participant 1: It's company. That benefits me. I'm glad to come out. I like the company.

Participant 2: Oh yeah. Now that I've got to know the others a bit better, there's different people to talk to and I ask them what they've done this week and this sort of thing. I didn't know anyone when I first came here, but now I'm always excited to hear what everybody has been up to and happy to share my own stories as well.

Participant 2: …and really … it's a purpose in life, I'm getting out, I'm doing something and whatnot. And then … well, we all have things to talk about. We get to catch up every week, we get to know each other better.

Whilst the social environment and co-presence of others were identified as important contributors to the co-construction of the experience and hence enabled social integration, in the sense of Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015), it also contributed to the development of a sense of belonging. Participants said they particularly enjoyed ‘being creative together’ and ensured they had put dates for these workshops in their diaries, as Participants 8 and 9 discussed in the example below:

Participant 8: There's Rural Arts, yes. This is a lovely place, yeah.

Participant 9: I mean, to have this in a small town, I think that's amazing! I'm so grateful.

Participant 8: I meant to check the dates because I came to, there was a coffee morning, coffee and crafts morning for the over 75s, there must be another one coming up soon. I love these arts and craft sessions, I must find out when it is so that I can come.

Participant 9: Yes I think this, being here a bit more as a taster, tasters is very good isn't it? ’Cause people think ‘oh I like that’ and perhaps book on a course so they can do more of it and get to know the other people a bit better.

Furthermore, the social creative activity itself was frequently discussed as a very emotional experience (both positive and negative affect) and enhanced the process of socialising with others. This socialising and connecting with other people through creative activities, particularly at an older age, can increase people's quality of life through escape, companionship and self-identity formation, as previously argued by others (Greaves and Farbus, Reference Greaves and Farbus2006; O'Shea and Leime, Reference O'Shea and Leime2012; Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013; Carnwath and Brown, Reference Carnwath and Brown2014; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Pritchard and Sedgley2015). The activity itself becomes ‘a process for generating talk’ and, in these conversations, the recognition of self and others, reciprocity and empathy, and mutual learning, reflection and support develop (Carter and Everitt, Reference Carter and Everitt1998; Maidment and Macfarlane, Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2009, Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2011).

Our research findings show how the participants’ positive/negative affect, expressed emotions and their perceived emotional synchrony are crucial elements in this socialisation process. Through regular participation in social creative activities, emotions can act as a conduit between the creative experience and the enhanced sense of belonging (Massey et al., Reference Massey, Edwards and Musikanski2021), as illustrated in the example below where participants in the North group had created wicker stars:

Participant 10: I thought it was great, I really enjoyed that one.

Participant 12: I did too, I did enjoy it. I didn't think I would at first because it didn't feel creative enough if you know what I mean, I was very worried. But then we were being told how to … how to do it, you know, so … But like you I was very pleased when I actually came out with the end product that actually looked like something.

Participant 10: Looked like something for once, yeah. I felt the same, I wasn't quite sure about it at first … but then they explained, step by step. It was different to what we did last week with the glass painting, wasn't it? They just told us to do whatever we wanted and we sort of just figured it out amongst ourselves. Which was a bit scary, wasn't it?

Participant 12: Different, yes … So actually, I didn't mind it in the sense that it was a different sort of thing, this week it was being sort of said ‘if you do this and this and this and this, this is what you'll get’ and there it was and that's good you know in the sense that if you want one of those, this is how you do it, you know. So that was good.

Participant 10: Yeah, I feel the same, I'm very grateful, sometimes it's nice to just be told what to do and how to do it – and you know, we felt a lot more relaxed about it, I think. You know, we've learned that now.

Our observations during the activities also revealed examples similar to this, where participants individually went through an emotional experience, but, as Zumeta et al. (Reference Zumeta, Oriol, Telletxea, Amutio and Basabe2016) pointed out, these emotions can often be influenced by the emotions perceived in others. In this case, when reflecting on the experience, both participants felt comfortable sharing their emotions with each other, which strengthened their friendship and sense of belonging to the group. As previously highlighted by others (Rimé, Reference Rimé2007; Salmela, Reference Salmela2012; Wood and Kenyon, Reference Wood and Kenyon2018), we all have a strong need to believe that we feel the same as those around us, and this belief enhances our sense of belonging and connection to others (Pinel et al., Reference Pinel, Long, Landau, Alexander and Pyszczynski2006). Our findings hence reinforce the argument of Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015) whereby the collective behaviours and experiences helped to enhance positive affect, particularly when the shared emotions were perceived to be similar within the group, which in turn reinforced positive social beliefs and social integration.

Sense of self-worth

Developing a sense of self-worth was also identified as an important wellbeing outcome of engaging in social creative activities. The content of each session and the creative challenge thereby enabled this process, as was also previously found by Liddle et al. (Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013) and Gallistl (in press). Across all our data, many participants spoke about how the process of doing something different and learning new skills was a physical as well as an emotional challenge at times. This challenge, although perhaps uncomfortable at the time, is important in developing pride and self-worth and thus enhancing wellbeing (Jenkins and Mostafa, Reference Jenkins and Mostafa2015; Narushima et al., Reference Narushima, Liu and Diestelkamp2018). The codes ‘creative challenge’, ‘sense of achievement’ and ‘feeling proud’ were among the most frequently identified in the data, particularly once cross-referenced with ‘positive affect’ and ‘negative affect’. However, due to the complexity of shared emotions, it is important to acknowledge that the processes, drives and outcomes vary by occasion, group, mood, personality and motivation (Scheler, [1913] Reference Scheler and Hamden1970). We therefore present two different examples below.

In the first example, Participants 8 and 9 (North) reflect on the experience of finding the right coloured tiles to be able to finish the product in the end. They worked together during the activity and bonded over the creative challenge of choosing different coloured tiles, as described in the researcher notes below. During the interview the following week, they express their own felt emotions working through this challenge, as well as highlight their perception of emotions felt by others (‘I think we were all a bit stressed at that point’; ‘we all felt very proud indeed’):

It is week 2 with this group and today's activity includes creating a mosaic. The session leader has nicely laid out the different coloured tiles on the main table. Most of the women are sitting around the main table, but some have formed smaller groups of three or four and are sitting at another table nearby … I walk over to participants 8, 9 and 12, who are sitting together; I remember they were chatting at the end of last week's session too and seemed to get on well. Right now they are discussing different designs and colours. Participant 8 asks the other two for advice on which colour to go with for the final bit. With the help of the session leader, they hold up different options for her to see – white, orange, red, purple – and they debate which one to go for. Participant 8 seems torn, she likes both white and red, but can't quite make up her mind. (Researcher notes, 5 March 2018)

Participant 9: Well I wouldn't say I was anxious, I didn't know I was anxious, but if I come across as I've been anxious…?!

Participant 8: We were looking for different coloured tiles then, weren't we? So maybe you were making a big decision?

Participant 9: Well I definitely got panicky at the end when I couldn't find any tiles. I needed 15 white tiles and 15 red tiles and I couldn't make my mind up, that was my problem. Yes and thinking about that, I think we were all a bit stressed at that point.

Researcher 3: You both managed to finish it though?

Participant 9: Yes, I took mine home. It's in the kitchen.

Participant 8: Mine is too. I've got it propped up, I want to look at it. It's quite an achievement for me because I'm not particularly crafty. But I'm very proud of what I've achieved.

Participant 9: Oh yes, very proud … we all felt very proud indeed.

The individual and shared emotions were crucial elements of our participants’ creative experience and further enhanced their sense of self-worth. The ‘emotional coming together’ in this example shows how experiencing the challenge together as a group can create motivation and a shared sense of pride once successfully completed, similar to the finding of Liddle et al. (Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013) where arts and craft activities helped participants not only to complete items, but also help others and be valued, as well as enjoy the moment together. The environment and physical setting was a contributing factor in this, where sitting and working together created a sense of togetherness for the three women. Talking about and reflecting on the experience together the following week enhanced their sense of pride, achievement, and hence self-worth, even further.

We must also acknowledge the vital role of the artist facilitator in this process. Their skill in bringing the group together and being part of it was commented on often by the women. In particular, participants appreciated the patience, skill and infectious nature of the artists who led the sessions, commenting ‘she's such a bubbly, cheerful person she's lovely’ (Participant 10). It was also noted how confidence was built though their understanding approach, relieving what could have been pressure to finish, as Participant 12 of the North group observed:

I did a dolphin [silk painting] and it was quite straightforward ’cause they were big pieces … but Hetty's was quite involved and she'd got behind and she [the artist] just said ‘don't worry Hetty, I'll finish it for you’. You know I just thought ‘she's lovely’.

In the second example, our group in the South also went through an intense emotional experience when building 3D models (animals, planes, cars, etc.). Individual felt emotions were quite different at the start (they varied between positive affect through enjoying the challenge, to negative affect in terms of anxiety and frustration), but participants later appeared to synchronise their emotions as they saw the final products coming together. The researcher notes from one of the sessions summarise this process:

The 3D models are quite fiddly and some participants are struggling with the little pieces. Participants 1 and 3 are working together on a penguin, they both seem very confused. Participant 3 is getting annoyed and says, ‘I just can't figure this out!’ Participant 1 is slightly more positive in her approach, ‘the instructions are really hard to read, but I really want to try this. I'm excited, I've never done anything like this before.’ I recall last week's discussion with them. Participant 1 spoke about how she enjoys a new challenge, how she feels excited when first introduced to the task. Whereas participant 3 confessed a new creative task makes her feel anxious and a bit frustrated; she struggles with her eyesight and frequently relies on others in the group to help. It is nice to see them working together again during today's activity, it seems participant 1 is keen to encourage her friend to keep going … The session leader comes over to help them make a start now and soon enough both their faces light up as some of the pieces are starting to come together; ‘oh look, this must be the penguin's tail!’ ‘Yes, yes, we've got it now.’ (Researcher notes, 24 January 2018)

Across all our arts and crafts groups, the most important element in enhancing participants’ self-worth was the joint ‘sense of achievement’ felt when seeing the final products they had created. In the discussion below, Participants 1 and 3 reflect on the very same experience of creating the 3D wooden models the week after. The example highlights the development of actual emotional synchrony, rather than merely desired emotional togetherness (Schmid, Reference Schmid2009; Salmela, Reference Salmela2012):

Participant 3: Oh, I thought [the model making] that was a bit fun every time I got my airplane stood up…

Participant 1: I needed some proper glue, I got a bit fed up when mine didn't stand up.

Participant 3: I enjoyed that. I like a bit of a challenge and trying new things. It was a team effort to actually finish it. We all fiddled around with it and got a bit annoyed, I think.

Participant 1: Yeah, I enjoyed doing it but it was quite frustrating at times. Everybody said afterwards though, they were pleased and proud and excited to show their partners, friends or whatever. I like moments like this, when we all achieve something together. We've known each other for a while now, haven't we? And it's nice to experience this together every week.

It is clear to see that the elements of empowerment (individual and collective self-esteem) and identity fusion (fusion between the self and the group), in combination with the positive affect, contribute to the perceived emotional synchrony within the groups here. As expressed by Participant 1, it is even more beneficial to engage in these activities on a weekly basis; the process of repeatedly engaging in creative activities with others thereby enhances the sense of belonging and self-worth, and potentially, therefore, reduces loneliness in older women over time.

Discussion and implications

Our aim was to explore perceived emotional synchrony as the theoretical basis for understanding the process through which regularly engaging in social creative activities can enhance a sense of belonging and self-worth in women aged over 70. More widely, we aimed to better understand the positive benefits of active, rather than passive, social activities, such as merely watching a film or listening to music together. We identified that previous research tends to focus on the immediate impacts of such activities, rather than the longer-term effects of repeated emotional engagement in activities with others.

We were not attempting to measure change as such but to explore how these women talked about belonging (or not) and expressed their feelings of self-worth in relation to the group and the activities. The emotional togetherness emerged as the sessions and the discussions progressed, and in these conversations it became clear that this was a vital part of feeling togetherness and being valued by others.

In this context of social creative activities, we explored a number of different experience enablers (being out of the house, creativity/challenge and social activity) in relation to the development of a sense of belonging and self-worth. It became clear that emotional synchrony played an important role throughout the process of developing these personal benefits among older women whilst engaging in creative activities together (see also Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013). We aimed to explore the process and the cumulative effects of social interaction and participation over time, rather than merely investigating the effects of one-off experiences.

Our study revealed how a sense of belonging and an enhanced sense of self-worth developed through participation in social creative activities. This, however, was only possible through the regularity of occurrence in that participants were able to develop emotional synchrony (real or perceived) through repeated engagement in activities with others over time. The continuity of social group and shared experience over the weeks enables two vital ‘effects’ within the Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015) model: social integration and identity fusion. They happen as a result of the emotional synchrony developed by having an activity in common which requires some challenge to be overcome and/or creativity to be expressed. This echoes Schatzki's (Reference Schatzki and Zembylas2015: 18) view of creativity as a shared ‘spatio-temporal nexus of doings and sayings’.

Theoretical implications

Figure 3 encapsulates our findings as virtuous cycles where regularly occurring social creative activities build a stronger emotional connection. Central to the model is the emotional synchrony created and, in turn, encouraging the effects noted by Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015). These move between individual emotions and shared emotions, and are again self-perpetuating in that a shared purpose enables social integration (underpinned by emotional synchrony) which leads to identity fusion. Identity fusion creates positive affect, which strengthens self-identity (within an emotionally synchronous environment) which then creates a stronger desire for a shared purpose or activity, and the virtuous cycle continues.

Figure 3. The virtuous emotional synchrony cycle.

For our participants this process became particularly apparent during the later stages of each session, as the final artefacts started to come together, and participants felt a shared sense of achievement. Whether the emotions experienced during this process were ‘real’ or ‘perceived’, as outlined by Páez et al. (Reference Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk and Zumeta2015), appeared to matter little – the effect is the same. The emotions expressed as a result of the emotional synchrony cycle move between individual and shared, with the sharing enabling the less-positive individual emotions (anxiety, lack of confidence, frustration) to become stronger positive feelings of pride, joy, self-worth and self-empowerment.

The environmental factors which allow this cycle to flourish, for our participants, have been identified here as being out of the home experiencing something other than the everyday; undertaking something that requires creativity and/or challenge; being with others who are undertaking the same challenge/activity and doing this on a repeated basis. The ‘sparkler effect’ of a one-off event or activity will clearly fade whereas regular social creative activities, with at least some group consistency, allow for the development of emotional synchrony over time. Observing and talking to the women over an extended period of time, hearing their stories of their younger lives and their current lived experiences, allowed us to better understand the cumulative effects of social creative activities in creating a sense of belonging and self-worth. The opportunity to also have meaningful conversations with their peers and to feel listened to enhanced this and therefore the discussion groups became part of the process for developing belonging. The cycle, therefore, represents the relationships between these different elements, which can be regarded as key factors in improving the quality of life of older people (see also Wood et al., Reference Wood, Jepson and Stadler2018).

This may be generalisable to other types of repeated art and leisure activities where there is the opportunity to include similar elements of experience (Maidment and Macfarlane, Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2009; Chaudhury and Oswald, Reference Chaudhury and Oswald2019). However, we acknowledge that the model's applicability in varied settings will need exploring in future research. We also recognise that there were many factors at play that were specific to the context of our groups. For example, the personality, gender (female) and facilitation style of the artist were clearly important and highly specific to our groups. ‘Getting out of the house’ was viewed positively but, for our participants, this meant a short trip to a known venue and may not have been as pleasant an experience if travel was more difficult or the location less familiar. For our research, the creative sessions were designed and delivered with the aim of building self-confidence and belonging. The same outcomes may not accrue in other activities where this has not been considered from the outset.

Practical implications

In terms of practical implications, we suggest that wellbeing interventions should not merely be one-off ‘special events’ or activities with a steep effect decay curve, but rather multiple smaller experiences building social connections and developing commonality between participants (Chapin Stephenson, Reference Chapin Stephenson2013), and developing the ‘symbolic wholeness’ identified by Liddle et al. (Reference Liddle, Parkinson and Sibbritt2013: 337). For example, regular trips to galleries or museums with others (monthly or weekly day trips) can provide a catalyst for discussion and feelings in common, which – as highlighted in our virtuous emotional synchrony cycle – create emotional synchrony between participants and therefore result in a sense of belonging.

Some element of creativity and/or challenge can further enhance this process and develop a stronger sense of self-worth among participants. The value gained comes from sharing experiences with others or in being valued for the artefact produced (Gallistl, in press). We saw this in the pride shown when our participants told of the praise they had received from family members when showing or gifting what they had created. The activities do not have to take place in the same venue each time and might include, for example, a visit to a botanical garden that includes a flower-arranging workshop, a photography tour in a historic town or a pottery day in an artist's workshop. In this way they become out-of-the ordinary, result in an artefact, and create social bonds through their regularity and consistency of group. Such social creative activities within leisure and tourism still tend to focus heavily on the family market but could easily be extended to cater better to the over seventies.

Activities that might increase belonging and self-worth can also benefit from creating inclusivity in the planning process and engaging other stakeholders in the co-creation of these experiences, particularly when there is no permanent relationship with customers (Moody and Phinney, Reference Moody and Phinney2012; Carù and Cova, Reference Carù and Cova2015). Social creative activity organisers can draw on the participants’ collective emotional experience to better understand their individual feelings of togetherness and belonging, and tailor products and services accordingly. Smaller community centres or venues, for example, are particularly well-placed to develop this aspect, being locally based and able to develop continuity of group experience over time and a strong social bond between participants (Chaudhury and Oswald, Reference Chaudhury and Oswald2019). In line with Gallistl's (in press) study, our research also suggests that arts-based interventions need to be considered beyond the personal benefits, recognising the wider value of these activities to individuals, their families, the community and society, ‘moving away from the idea of arts-based interventions and towards artistic co-production with older adults’.

It is worth noting that in the rural areas where we undertook our research, there were several barriers to the implementation of such activities. Participants often mentioned the lack of transport which severely affected their ability to get out of the house and experience new things with others. Funding of activities also tends to be sporadic, leading to a lack of continuity of activities and limiting the establishment of regular sessions. Togetherness and a sense of belonging, however, is particularly important in rural and remote communities (Hennessy and Means, Reference Hennessy, Means and Walker2018). The charity sector, social care and community arts providers should therefore work together to enable better access for all. In our sampled regions, at the moment, there is a heavy reliance on charities and the willingness of volunteer drivers as a temporary solution to this issue.

Lastly, our findings also have implications for leisure and arts policies to be better integrated into wider policies for ageing populations. The social benefits of art and leisure in general have been well explored, and particularly for older adults (e.g. Patterson, Reference Patterson2006; Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2007; Maidment and Macfarlane, Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2009, Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2011; Bennington et al., Reference Bennington, Backos, Harrison, Reader and Carolan2016). Our research adds more detail to how these benefits might be best achieved for women over 70. Those at greater risk of social isolation and loneliness would benefit from social creative activities not being seen as on prescription but simply being made accessible, attractive and affordable (Cantu and Fleuriet, Reference Cantu and Fleuriet2018). This relatively low-cost approach to tackling a larger-scale social issue could reduce reliance on social services and health-care providers whilst creating a far better quality of life for older generations.

Limitations and future research

We acknowledge that there are limitations in our approach as the discussions and observations are all potentially subject to researcher, environmental or cultural bias. We therefore recognise our position within the research in that we, the researchers, potentially became part of (or at least had some influence on) the collective emotion co-creation process, and acknowledge that any interpretation of the data should be performed with care. We do, however, echo Hennessy and Walker's (Reference Hennessy and Walker2011) call for greater inter-disciplinary research within ageing studies which is potentially interpretivist and humanist in its approach.

Despite having a relatively large sample for an in-depth qualitative study, we also recognise that the results are highly personal to each individual. Generalisability is therefore mainly through the theoretical implications of our findings. Further research is needed to corroborate the results and to explore their applicability in other socially active settings and other cultures. As our findings also highlight the benefits of talking with others about the experience, we would also suggest further research into how the social creative activities create emotional synchrony and value beyond the group, such as when talking about the activity with partners, family, friends, and in showing and sharing the artefacts created.

Our population was women over 70 in order to redress the gender imbalance within such studies, but we also recognise that the same issues, loneliness and isolation affect men of this age. It may well be that different elements of social activities have a stronger impact on this group. We therefore recommend similar studies with male or mixed-gender groups. Furthermore, our focus was on social activities with an element of creativity and although this was found to play an important role in developing emotional synchrony and feelings of belonging and self-worth, it may be that other activities could have similar effects. Future studies might therefore follow less-participatory experiences, e.g. museum tours, coffee mornings, quizzes, physical activity and theatre trips, to ascertain the importance of ‘doing together’ versus just ‘being together’.

Our own further research will focus on follow-up studies with the same groups in order to better ascertain the longer-term effects of group creative activities. This will be particularly interesting following a period of enforced isolation due to COVID-19 restrictions and the restarting of group activities.

In conclusion, we have found further evidence of the value of being creative together (Gallistl, in press) and have identified the importance of emotional synchrony in this process. As Maidment and Macfarlane (Reference Maidment and Macfarlane2009: 24) argued, ‘[such] self sustaining low cost [craft] groups operate throughout the country, quietly making significant contributions to the social and cultural capital of our community, while nurturing the lives and achievements of older women’. Our research further evidences the need to recognise and support these groups at a policy level.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Age UK North Yorkshire and Age UK Hertfordshire for their support for the project and allowing access to their activity groups. We would also like to thank Rural Arts, Thirsk for developing and delivering the creative activities in the North of England study and our research assistant, Dr Sam Isaacs.

Financial support

This work was supported by Age UK North Yorkshire and Age UK Hertfordshire.