This article studies a social force that has been overlooked in existing scholarship on the 1979 revolution, namely those industrial workers who, as part of the Iranian political spectrum, were presumed to have led a progressive political grassroots movement, but who showed little desire to change the status quo during the political turbulence leading up to the Iranian Revolution.Footnote 1 Although, Quataret states that Iran has been an exception in the Middle East with its considerable scholarly involvement with its labour history, it must be noted that the scholarship has been mostly devoted to the political role of workers and its relationship to the organisations and unions.Footnote 2 In fact, “the history of the working class in Iran consists of accounts from trade unions, with a particular focus on the period between 1941–1953, rather than a history of laboring men and women, their work, community, culture, and politics.”Footnote 3 Moreover, those engaged with workers and the 1979 revolution have neglected the existence of diversity within the working class to draw a portrait of unified workers as a revolutionary force, promoting their involvement in protests during the course of the revolution. Aside from Ashraf's sociological study examining the nature of industrial workers’ demands in the 1970s, and particularly during the political protests of 1978–1979, to show the existence of a lesser revolutionary potential, other studies—including those of Abrahamian, Bayat, Moqadam, Halliday, Jafari, and Parsa—have been inspired by the radical movement against the shah and highlighted the revolutionary nature of these workers.Footnote 4

This article examines the making of the worker-peasant, and then the reluctant revolutionary industrial worker during the establishment of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine between 1966 and 1979. I focus on labor relations that comprise the engagement of different agents with substantive new rules regulating the employment relationship, including methods of control, wages, hours of work, and other factors. I also scrutinize the procedural rules encompassing management and control of the relationship between employer and employees, such as for bargaining and dispute resolution.Footnote 5

The argument I present also takes into account the nature of capital as represented by a domestic private company, an international contributor, and the Iranian state: ownership, management, the composition of the workforce, labor formation, labor migration, and living and working conditions. These factors all contributed to shaping labor development at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine and led to the making of the reluctant revolutionary industrial worker. This point particularly refers to the imposition, at different stages, of new conditions from above interacting with the ways that the workers themselves, as well as local society, contributed to the formation of their living and working conditions.

I maintain that, in the absence of workers’ associational power at the copper mine, the workers’ structural power (including a labor shortage and local workers’ landownership as well as their agency manifested by different demands, including petitioning), along with, on the other side, the role of private capital, state capital, and international companies, inspired the development of the Iranian copper industry, forming a structure that led to more developed labor relations, better working conditions, and overall economic improvement for the workers.Footnote 6 This in the setting of the poor economic background of the laborers contributed to formation of reluctant revolutionary industrial workers and negative class compromise, based on Wright's definition of class compromise, the indications of which emerged during the unrest of Iran's 1979 revolution.Footnote 7

This article is the first case study of the relationship between a labor force, local society, and a mining company shaping reluctant revolutionary industrial workers in a mining industrial workplace in the Pahlavi era. The study has relied on oral sources as well as documentary texts. Iran's labor history has suffered from a scarcity of written documents, requiring me to rely significantly on oral sources. I conducted semi-structured interviews with retired workers, former senior managers, and local residents. I also visited several archives, both private and public. Some oral sources allowed me to cross-check publicly accessible archives, particularly authorized documents, and avoid presenting an official and biased narrative. However, I could not verify all oral sources, such as those I personally uncovered by conducting interviews. These remain to be verified, or not, by general consensus of the scientific community after publication.

The first section of this article outlines the early exploration of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine, which was carried out by a domestic private company. I examine welfare policy and labor relations in an attempt to account for the poor status of labor development at that time. The second section describes the participation of a British company in the exploratory operation and how significant changes occurred in the company's approach to labor policy and the betterment of workers’ living conditions. In the following section I discuss the nationalization of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine and the role of the state and an American company in the transformation of welfare policy and labor relations. The final section concerns the workers and the 1979 revolution, and the extent to which improving material conditions for laborers and their poor economic background determined their political orientation during the revolution.

Early Exploration: Domestic Private Ownership and Poor Labor Development

Iran's copper industry was founded upon the world's second largest copper ore deposit, at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine in the Rafsanjan region of Kerman province, during the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 8 Rafsanjan was a major city that had a population of 21,425 in 1966, a city with which the Sarcheshmeh rural district was closely linked both economically and socially. Agriculture had employed most of the region's workforce, including Sarcheshmeh inhabitants; they were arable farmers, or worked in animal husbandry.

The Sarcheshmeh region was deprived before the start of explorative operations in 1966. Poverty was rife, and, with the exception of a few major landowners, most struggled under the harsh conditions. The diet of the peasant population was very poor, deficient in vitamins and protein, especially for young children.Footnote 9 The rural population suffered from a shortage of rudimentary services such as clean water, electricity, and medical care. The vast majority were illiterate due to the lack of educational services in the area. Reza Niazmand described Sarcheshmeh in following words:

On my first visit to Sarcheshmeh there were a few families who lived like people of the Stone Age. There were no facilities and no wealth. Each family had huts dug two metres down into the ground and they used tree branches for rafters. Some people even kept their goats in their huts. Each family had a few walnuts trees and a small piece of land, around 200 m2, which was planted with vegetables. None of them had ever seen a bathroom, or a school––let alone a doctor—in their lives.Footnote 10

Social stratification in the Sarcheshmeh community during the 1960s was similar to the general hierarchy of rural areas in Iran, characterized by peasant proprietors and landowners, sharecroppers, and tenant families, as well as landless villagers known as Khushneshin.Footnote 11 In addition, Sarcheshmeh hosted seasonal immigrants from the city of Rafsanjan, on the hunt for work at harvest time.Footnote 12 There also were traders to facilitate economic relationships between urban areas and the countryside, exchanging rural produce in the cities. Wealthy locals usually left the area during the winter to avoid the worst of the weather.Footnote 13

Contrary to growing industrial development elsewhere in Iran during the 1960s and 1970s, for many years industry had no significant place in the economy of Rafsanjan. The figures show that only eleven licenses were issued to establish industrial plants in the Rafsanjan area, employing 323 workers.Footnote 14 However, the Sarcheshmeh copper mine transformed the region into the hub of the copper industry in the Middle East and North Africa and catapulted Iran into prominence as an emerging competitor in the world copper market.Footnote 15

Early exploration at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine began in 1966, and the mine was ready for operation in 1979–1980. I will trace various outcomes of those years by considering three specific time periods, based on the type of ownership and mode of management of the mine, as follows:

• Kerman Mining Corporation (KMC), a domestic private company which was owned and managed by the Rezai brothers, from 1966 to 1967.

• Kerman Copper Industries (KCI), a company jointly owned and managed by the Rezai brothers and a British mining company, Selection Trust, from 1967 to 1971.

• Sarcheshmeh Copper Mines of Kerman Corporation (SCMKC), owned and managed by the Iranian state, with the American company Anaconda acting as consultant, from 1972 to 1979.Footnote 16

Each of the three periods featured a distinctive stance on industrial relations. To achieve early adaptability as well as production of labor power for industrial conditions, the companies applied different means to control the workforce and impose a new order. Recruitment policy, wages, job promotion, training, disciplinary actions, and a welfare policy including housing and accommodation shaped the company's approach to labor relations.Footnote 17 Labor relations followed two classic models, coercive and paternalist, organized along different lines, which derived from the type of employer, social and economic conditions, nature of the work, and traditional labor relations.Footnote 18 The coercive model looks back to the period when forced labor was lawfully practiced around the world. The response of early capitalist employers to labor shortages was to institute coercive practices, particularly in colonial states.Footnote 19 Workers were often monitored in the workplace, and strict rules might be introduced, such as a ban on talking to fellow workers or even whistling.Footnote 20

The transformation of social relations, the nature of the workplace, and increased consideration of human rights, coupled with the limitations of a coercive system when it came to labor efficiency, heralded the widespread decline of coercionist discourse; eventually a paternalist approach to labor relations emerged.Footnote 21 The idea of paternalism was principally a response to forced-labor employers and coercive labor arrangements. Management employed both persuasion and repression, with the objectives of attracting workers to industry and boosting their productivity.Footnote 22 In France, the scarcity of both skilled and unskilled workers led to the growth of industrial paternalism in the nineteenth century. Companies began offering housing, schools, health care, and other social services to create more enticements for the labor market.

In Iran, the oil industry was one of the earliest workplaces to introduce a paternalist policy.Footnote 23 However, this was not well received across business sectors, particularly by private enterprises, and many tried to preserve the spirit of coercion that existed within the traditional system of the landlord-tenant relationship. This traditional relationship was practiced in the agricultural sector until the 1960s. Then, the Iranian state implemented a critical program of land reform that determined the land ownership of large landowners and attributed land to the peasants. The program restructured the power relations of the countryside and demolished the dominant system of landlord-tenant obligations. However, some industrial owners, who primarily had trade backgrounds and no professional experience in mining and industry, had a narrow vision of industrial organization and tried to preserve the traditional spirit of the landlord-tenant relationship, particularly to increase surplus value from a cheap labor force.

The KMC's founders, the Rezai brothers, did not have an extensive industrial and mining background. They primarily had been involved in trade and retailing, from running a luxury boutique to importing cigarettes and fabrics.Footnote 24 They were persuaded by Iran's industrialization plan to change their line of business and go into mining, including multiple mines for different resources (chromite, copper). The government's concentration on industry and its provision of facilities laid the groundwork for the private sector to shift its business activities toward industry and mining. Alinaqi Alikhani, Minister of Economy from 1963 to 1969, once said “Iran was a unique country in the world in the 1960s in its consideration of giving priority to the private sector. The state's income came mostly from oil, not taxes, and that gave them great power over the private sector, but our treatment of the private sector was much more tolerant than that found in other countries such as Turkey, India, and Egypt.”Footnote 25

The rise in oil income enabled the state to allocate sufficient credit to the private sector for development of businesses in the 1960s and 1970s. In addition, high inflation led to enormous profits from trading of land, which enabled large real estate holders to accumulate capital. Moreover, the import substitution policy put in place to support the development of domestic goods, for instance the offering of loans at low interest rates, persuaded a number of the Iranian merchant bourgeoisie and traditional landowning families to change their field of business to manufacturing and industry. The KMC's founders were among them. As a result, without previous experience in managing a large mine site, the Rezai brothers became owners of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine. Their method of management entailed neither a developed vision of labor productivity in the industrial workplace nor a strict agenda for enforcing industrial discipline. They were inspired by the landlord-tenant relationship and viewed laborers as little more than serfs who were obliged to work very hard for little remuneration.

The next sections examine the conditions of local labor relations, which did little to create a well-developed workforce system or foster labor efficiency and led to defining local laborers as worker-peasants rather than industrial workers.

Training and Industrial Discipline

The remote location of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine was partially responsible for KMC's labor recruitment plan. Despite the inevitable skill deficit of local workers, the goal was to keep labor costs down by hiring the unskilled local laborers and training them, rather than employing people from outside.

Many local peasant farmers and landless villagers were absorbed into the labor force. They were unskilled, with no experience in industrial employment, much less in mining. Moreover, they had been born and raised in an agrarian community and were totally unfamiliar with an industrial setting.Footnote 26 They had little concern for industrial discipline, including timekeeping and punctuality.Footnote 27 Since the company did not strictly enforce industrial discipline either, it took longer for local workers to adapt to the concept. The case was not unique; coping with the world's new industrial order varied according to regional characteristics as well as political and economic conditions. In the early 1900s, during the establishment of Iran's oil industry, laborers with nomadic and rural backgrounds had difficulty adjusting to the imposed discipline of the workplace, and some even left their jobs.Footnote 28

This also affected other aspects of the workplace, such as training. The Rezai brothers transferred a technical team from their chromite mines in the Esfandaqeh and Faryab areas, also located in Kerman province, to the Sarcheshmeh copper mine for training purposes. However, the instructors’ outdated knowledge shaped a group of workers whose skills were obsolete, leading to increasingly hazardous situations and reducing labor productivity. For instance, the ends of tunnels were not ventilated, not even by compressed air, airways were not correctly positioned for workers, and supply hoses were too long. Therefore, low levels of oxygen and the long hoses soon caused breathing difficulties that exhausted the laborers. As a result, each tunnel location needed five workers as well as backup, whereas with well-established practices the number of workers required was only three, with no need for backup from a specialist team.Footnote 29

Recruitment and Wages

KMC's tenure ended in 1967 with nearly sixty paid employees at the mine.Footnote 30 At first, the small scale of operation combined with chronic local unemployment made recruitment easy, and the company did not face a labor shortage. Early recruitment of the labor force was centered on a number of locals whose living conditions improved during their employment at the copper mine; one former worker described it as a transformational event in his life. He was initially employed at the age of thirteen as a water carrier, to distribute drinking water among the workers as well as pour water onto the drills to cool them down. His starting wage was 42 rials per day in 1966. Three years later, in 1969, his wage increased to 65 rials per day for work as a tunneler.Footnote 31 The payments were around minimum wage according to Iran's labor law, indicating that the company benefited from a growing capital surplus generated by minimizing welfare facilities and labor payment.Footnote 32

KMC recognized overtime, however the payment was made under a different title, called bakhshesh, which means gratuity, tipping, or charitable giving, according to the Dehkhoda Persian dictionary. This exposed KMC's reductionist view of labor relations determined by the labor law. A gratuity payment was often appreciated in society, but neither the force of the law nor social pressure obliged people to tip or pay a gratuity. Calling the overtime payment a gratuity labeled it as the employer's right rather than the laborer's. The employer decided whether or not to issue a gratuity payment. However, this reduction in the status of the laborer was limited to the discursive level, as KMC did not actually neglect to make the overtime payment. It is rather an indication of the employer's intent to preserve its authority by reviving a traditional labor relations discourse, generated from the landlord-tenant system, in which the employer retained a meaningful upper hand in relation to the employee. The formula for determining the overtime payment was not transparent, as the labor cards just stated that overtime was paid, without an exact sum being declared.Footnote 33 This lack of transparency kept labor rights unclear, enabling the company to keep the level of payment down without any approved documents, giving it more control over the workforce.

This displays a backward mode of management, without a vision for development of industrial organization and relations. Moreover, it confirms the state's lack of inclination to impose the rule of the law in support of workers’ rights against a private employer, dictated by a governmental process that was controlled by a group of men who primarily came from important landowning families. The same group of people also occupied cabinet posts, other senior civil service posts, and commissions in the armed forces.Footnote 34

Alongside the lack of intention to implement labor law on the employer's side, the situation also discloses the workers’ lack of awareness of their rights. These gaps in labor awareness and implementation of the law, and the fault line that existed between the employer's view on labor relations and the labor law, generated an exploitative condition, in which the employer, here KMC, used labor malpractice to preserve its dominant position in labor relations.

Accommodation

Most of the local workers had been living in villages a long way from the mine site. The company built two accommodation blocks for the laborers and one block for the trained staff, but the poorly appointed buildings could barely stand up to the severe weather. Roofs were not waterproof; even light rain was driven into the accommodation. Once, a roof was blown clean away by a gust of wind.Footnote 35 The blocks were not divided into separate rooms; all the laborers lived together.Footnote 36

This lack of concern about laborers’ accommodations again derived from the long-embedded landlord-tenant structure. This relationship was nurtured by reviving the traditional hierarchical culture in which the worker was identified as a serf, whose provisions met only the basic living and working needs. This was very much the case in the mining sector, chiefly due to the configuration of the mining industry in Iran which, at the time, was undeveloped and a labor-intensive operation that relied on cheap labor to generate surplus revenue.Footnote 37 Moreover, the rough nature of the work absorbed workers with poor job prospects who had no choice but to accept the conditions, with little awareness of their labor rights including payments as well as health and safty in the workplace.Footnote 38 At the Sarcheshmeh copper mine, the workers were usually landless villagers.

KMC flouted the development of a welfare policy, signaling absence of a strategic vision regarding labor practices. The company preserved the framework of traditional labor relations whose structural function was reproducing landlord-peasant relationships. KMC as an industrial organization distanced itself from its key structural duty of producing an industrial worker through implementation of industrial labor relations, instead creating a worker-peasant.

Local Resistance and Conflict Resolution

The establishment of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine was generally welcomed by most local residents, including the landless villagers, since the company created job opportunities. However, the vigor of capital and industrial discipline reorganized the social structure and set up new institutions, leading to the transformation of the dominant agrarian order into an industrial society. Agents of traditional order in the host community occasionally undermined the authority of the new order. To manage these issues, KMC applied a paternalistic approach, with an emphasis on justification and persuasion, rather than force and threat. In relations with workers, the managing director of KMC, Mahmud Rezai, strove to generate loyalty by mingling with the workers. One former worker said that Rezai was a humble man, treating the workers as though he were their father. On his two visits to the site, he shook hands with the workers and spent time talking to them.Footnote 39

KMC used the same approach to deal with challenges between the company and the local community. One concern arose from the threat to local land ownership. Most resistance was initiated by people who either owned land or had an influential status based on the traditional power structure in the local community. Inevitably, the project sometimes brought a level of tension to the area. One day, when a camera was set up for mapping, one of the locals stopped the operation, saying, “This is my property. What's this? I haven't died yet, but you're digging my grave.” The response was: “No, we're not digging your grave. There is an Emāmzādeh [Holy man] here who's going to make us all rich!”Footnote 40

KMC also asked the head of the village to mediate between the company and the local villagers. He was appointed as the residents’ delegate in negotiations with representatives of the company. The village headman's influential status convinced some landowners to sell their land to the company in exchange for shares in the mine and some future lifelong benefits.Footnote 41

Selection Trust: Implementing a Developed Paternalism

As stated, the Rezai brothers did not have the expertise to establish the oversize scale of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine. KMC therefore decided to run the project in partnership with a British mining company, Selection Trust. A joint company, KCI, was created, with day-to-day administrative management remaining in the hands of the Iranians and Selection Trust managing the overall operation on-site. This was in the late 1960s, when dominant colonialism had declined and the Global South embarked on a postcolonial era. International companies in undeveloped countries already had shifted to a paternalist mode of management, with a series of principles focused on welfare policies and improving labor conditions. In Iran, this had been distinctively practiced in the oil industry, which was controlled by international companies. Oil workers were held in higher regard than workers in other sectors.

The presence of Selection Trust began a new chapter for the mine. Selection Trust criticized KMC's traditional view then it alternatively instituted paternalism to enhance the employees’ living and working conditions, leading to a growth in labor productivity. To turn them into industrial workers, the company also aimed to detach worker-peasants from their previous source of income, land, encouraging them to create an economic life separate from their rural background.Footnote 42 For that purpose, KCI restructured the company and reconsidered its policies, with the intent of introducing a restrictive industrial discipline as well as modifying its view on labor relations and welfare policy. The company then endeavored to impose a new organizational discipline, designing places and creating spaces that would dictate an industrial order, breaking down the workers’ peasant boundaries and rural ties.

Wages and Training

The range of skills on offer in Kerman province was very limited in the late 1960s. Tradesmen such as carpenters, mechanics, plumbers, and electricians were very rare, especially those trained to a decent standard. The company decided to import labor from outside Kerman province, including Iranians from other ethnic backgrounds such as Armenians or Azerbaijanis.Footnote 43 Nevertheless, the local labor force that had grown up in an agricultural order remained the company's primary target for labor recruitment. Consequently, KCI confronted the challenge of introducing an industrial organizational hierarchy and setting the protocol for an organizational relationship. For instance, local workers were in the habit of walking into offices and interrupting conversations, demanding that their problems or requirements be addressed immediately.Footnote 44 This issue originated in their rural culture and the structure of relationships in the landlord-tenant system, in which landlords could be contacted directly by the peasants in their care.

After two years, in 1969, staff numbers had increased to 468, of whom 400 were locals, 60 were British experts, and 8 were Iranian experts.Footnote 45 More than 90 percent of the workers were from Kerman province, with some 75 percent from villages in the immediate vicinity of the mine.Footnote 46 As a result, 1,400 to 1,800 people as family members of the local workers benefited directly from the company; in the face of widespread poverty and famine at the time, the wage payment had considerable influence on their lives.Footnote 47 A tunneler was paid 65 rials per day in 1968–1969, and in an interview he stated that the wage was quite sufficient at the time.Footnote 48A rail track worker was paid 58 rials per day at the end of the Selection Trust period in 1970.Footnote 49 A driver holding a private driving licence was paid 216 rials, and a bus driver could earn 516 rials per day, equivalent to three to eight times more than a laborer.Footnote 50

KCI also planned a training system to educate the local forces and inexperienced personnel. The tunneling training team faced a challenge in instructing the local workers, because the older workers had already been instructed in inefficient and unsafe techniques by KMC. The instructors had to break the laborer's old habits and prepare the workers to carry out the same task with new techniques, consisting of a series of more advanced, efficient, and safer methods.Footnote 51 For drilling, which was a delicate operation and could not be done by the inexperienced local workers at Sarcheshmeh, KCI came to an agreement with a British company, Geoprosco International, on February 6, 1968.

Health, Food, and Accommodation

Accommodation during the KCI period improved in both quantity and quality, however the company did not reach its quality goals due to a rapid increase in the size of the labor force. The laborers’ blocks that had been built in the KMC period were merely renovated, with no extension in the early years. Space was insufficient for the number of workers, so as many as fourteen men had to live in one room.Footnote 52 The blocks for the laborers and technical staff were divided, so that upon entering the technical staff building one saw a corridor twenty meters long with doors to rooms opening to the left and right. Each room had two beds, and a lavatory was located at the end of the corridor.Footnote 53

At the end of 1969 more accommodation was added. Construction included four duplex accommodation blocks as married quarters; one block of ten single rooms; one block of twelve twin rooms; one block of eight double rooms; two double rooms in the mess block; one room for the doctor at the hospital; and a caravan and a two-bedroom house in Khatunabad.Footnote 54 By the end of KCI's term, there were thirty-one furnished buildings and an office, warehouse, laboratory, bar and restaurant, powerhouse, and pilot plant. Footnote 55

According to KCI's plan to provide basic facilities on site for the employees, the company built two new separate clinics, one for technical staff (including Iranians and foreigners), and one for the laborers. Class division also applied to other welfare services, such as food provision. Iranian and British technical staff shared the same canteen, and the laborers’ canteen was separate. The company prepared food for the laborers every day in exchange for some 60 to 70 rials a month, which was much lower than the real cost, and was deducted from their wages. The quality of the catering and food was good.Footnote 56

Leisure Time

Leisure time activities are a contemporary phenomenon, associated with the modern mode of everyday life. As a cultural phenomenon, they depend on other variables such as social structure, cultural institutions, and dominant value systems, as well as income, occupation, and education. The agrarian community of Sarcheshmeh was built upon traditional values, with keen attention to the rites and ceremonies of faith being a significant part of social life. Even when they became more accustomed to modern life, the preference of the local Sarcheshmeh workers was still to spend time at home with their families, or to visit relatives in their villages. Other studies acknowledge that this was common among workers from other geographical regions. More than 90 percent of workers in Arak said that their favorite leisure activity was spending time with their families. According to Bayat, even industrial workers in Tehran did not spend their time in the coffeehouses there; the coffeehouses were in fact mostly used by migrant construction workers and the homeless.Footnote 57 However, KCI's employees were not restricted to local residents; a significant number came from other provinces and countries outside Iran. As a result, leisure time was a major issue, as the nonlocal forces were in a remote area, far from their families, with limited social interaction. Financial privilege and a high salary were not always enough to induce people to work at a mining site such as Sarcheshmeh, and creation of a supportive atmosphere became a key concern of companies operating in such circumstances.

In the early stages, there were no leisure amenities on-site, making staying there difficult for nonlocal laborers and staff, especially for foreigners who had to spend four to four-and-a-half months on site without contact with their families. Local newspapers were at least one or more days late, and English language newspapers were even more out-of-date by the time they arrived.Footnote 58 However, conditions did improve. A movie projector was brought on site and a number of dartboards were set up for the use of staff.

Class Conflict and Land Use Conflict

Class relationship is not only determined by forces from above, but also by the workers’ agency, which can apply different means toward transforming dominant conditions. This agency can be enhanced by two sources of working-class power: structural power and associational power.Footnote 59 The former derives from the status of workers in a tight labor market as well as the location of a particular group of workers in the industrial sector, and the latter comes from labor organizations such as trade unions and labor councils.Footnote 60 Under certain conditions, these two power sources can back workers in negotiations and collective bargaining. They support initiatives that remove barriers impeding workers’ ambitions and oblige employers to consider labor interests. Moreover, at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine, the assembly of workers at KCI, mainly comprised of local manpower, on occasion was able to reshape the structure of class conflict because it could be merged with the land use conflict; landownership as a source of power gave local workers an advantage when negotiating with the company.

The Sarcheshmeh copper mine confronted a labor shortage at a certain point each year, affecting workers’ structural power. This arose from the long absence of workers on two occasions; first was the long national holiday of Nowruz (the New Year holiday), when it was expected that the workforce would be absent for two weeks. The second was at planting and harvest times, when some worker-peasants left their jobs to work on their own small holdings or on their landlord's land. Absenteeism was a concern of employers worldwide and occurred due to low job security, insufficient payment, and a backward welfare policy. For instance, in France in the nineteenth century, mining was a business that provided the lowest supplementary income to its workforce. Miners’ resistance was reflected in seasonal absenteeism as workers joined in regional grain, grape, or potato harvests, and in a preference for flexible schedules that allowed for their comings and goings.Footnote 61 To resolve the problem, business owners introduced permanent job contracts, increased wages, improved working conditions, and promoted social policies.

At the Sarcheshmeh copper mine, the laborers sometimes resisted industrial discipline in the workplace, specifically when a foreign supervisor was in charge. For instance, KCI expressed great concern about workers’ timekeeping and punctuality, whereas the local workforce paid less attention to it. In one case, a foreign supervisor who exercised rigid control was injured by a worker from Pariz, who had been egged on by fellow villagers. The company identified the attacker and dismissed him the next day.Footnote 62 However, the company sometimes was more lenient with local employees who were disobedient or misbehaved. For example, subsequent to KCI's offer, one small landowner traded a share of his land to the company, and also agreed to sell the rest later. The company offered him a job as a concession, to prevent him from making trouble and secure his cooperation in the future. However, this did not succeed, with the worker acting undisciplined and disobedient.Footnote 63 The Iranian managers tried to appease him, as the worker's landownership gave him some power. However the British had little knowledge of local power relations and questioned why the company did not bring disciplinary action against him.Footnote 64 Moreover, the state's interest was to keep the level of discontent down among local villagers. Then, a dispute between the company and powerful local employees could disrupt the mine's industrial development, causing financial loss for the company.

To express their discontent, the workers went on two minor strikes, lasting just a few hours. Both strikes were swiftly resolved with minimum conflict.Footnote 65 There was no collective bargaining because, in the newly established mine, the workers had not yet unified under a collective identity. Workers had little organizational power. Nevertheless, because of the company's welfare policy and the poor economic background of the local residents, the vast majority of workers at Sarcheshmeh copper mine were satisfied with the company.

As stated, the state had an interest in industrial relations, as reflected in the state's responses to petitions received from workers about their employers. Despite the fact that the Sarcheshmeh workplace had not become an organized “proletarian” environment, exhorting the company through collective bargaining, individual workers made personal demands by petition.

Petitioning is a worldwide practice, demanding “a favour or for the redressing of an injustice, directed to some established authority.”Footnote 66 It is a channel facilitating communication between the governor and the people. Despite the existence of a judicial system in Iran, each citizen could bypass this process and send a petition to the central authority, the shah. Petitioning the shah was a tradition in Iran.Footnote 67 After the Constitutional Revolution (1905–1909), petitions were submitted to the newly established legitimate power center, the parliament.Footnote 68 Reza Shah (1925–1941) reinstituted the practice of direct petition by the people to the shah, stating, “I am obliged to look after the oppressed and to liberate them from the oppressors. I will permit all my countrymen to bring their complaints directly to me and to request redress directly from me.”Footnote 69 The tradition of petitioning is rooted in the central government receiving the opinions and feelings of the ordinary people.Footnote 70 This helps the central authority avoid resistance brought about by a lack of concern on the part of local authorities in people's demands. The right to petition works as a safety valve.Footnote 71 Although petitioning provides citizens with the opportunity to express their demands and grievances, it also enhances the legitimacy of the ruler.Footnote 72 It also should be stated that the lack of labor unions or syndicates prompted workers to send their grievances to the shah instead.

Reviewing petitions presented to the Royal Investigation Office regarding some senior staff at Sarcheshmeh copper mine indicates that the office considered the demands, referred them to the appropriate authorities for further investigation, and followed up on the results. For instance, a petition to the shah from a local employee who had been dismissed expressed a complaint about Colonel Auhady, a senior company man who was head of security for KCI.Footnote 73 Auhady's power, which derived from his organizational position and his background in the Iranian army, did not cause the villager to hesitate to lodge a grievance against him. This challenge to authority demonstrates the worker's agency as well as the expectation that it would be considered by the central authority. In another petition, an engineer complained about what he claimed was the misbehavior of his British supervisor.Footnote 74 A driver complained about being dismissed from his job.Footnote 75 Tracing the correspondence regarding these petitions shows that the system proceeded in orderly fashion, and a decision was duly given.

Resistance was not always by soft power, such as petitioning, during the KCI period; unresolved conflict sometimes led to physical confrontations. Some local inhabitants were not persuaded to sell their land and move to a new place. They interrupted the exploration in a number of ways, such as blocking roads, lying down in front of bulldozers, and sitting on a location ready for blasting.Footnote 76 The village headman, Amiri, and KMC's advocate, Nikkhah, were appointed to negotiate with local villagers and justify the project. This was effective, but did not persuade all landowners to follow suit. At this point, Colonel Auhady, head of the company's security departrment as well as land purchesing, started to threaten the local residents.Footnote 77 The exploration operation damaged the environment and natural resources with chemical substances that polluted rivers and harmed agriculture and animals.Footnote 78 More residents decided to sell their land and migrate elsewhere.

Mahmud Rezai's meeting with the local community finally settled the conflict. The landowners came to an agreement with the company on a pension scheme that committed the company to paying a monthly pension to those who could not work for the company. The payment was between 2,000 and 4,000 rials per month, according to the scale of proprietorship of each individual. For instance, one landowner who had 14 habeh was paid 2,400 rials per month.Footnote 79 In 1968–1969, the company purchased the same land for 8,000 rials per habeh.Footnote 80

The State, Anaconda, and the Transformation of Labor Development

Iran's rich oil resources provided an easily accessed source of capital, which gave rulers a large scope for running ambitious programs and taking shortcuts in industrial development. This assured revenue encouraged the state to place great importance on the industrial and mining sector, with the intention of moving Iran's agrarian economy to an industrial economy. An oil income of $22.5 million in 1954 rose to $254 million in 1958 and reached approximately $342 million in 1962.Footnote 81 In just eight years it increased fifteen-fold. The wealth generated from oil was increasingly visible in society in the 1960s. The pace of modernization dramatically increased, and big cities like Tehran were glittering examples of modernity by the end of the 1960s.

The price of oil reached a new level in the early 1970s when the Arab-Israeli war of 1973 destabilized the crucial Middle Eastern oil region. As oil-shock dominated public discourse in Western countries, oil-producing countries saw an unprecedented rise in their oil revenue. Iran had a record $20 billion oil income in 1976, greatly amplifying oil's contribution to state income.Footnote 82

Rising oil revenue increasingly persuaded the state to step into supersize projects such as the Sarcheshmeh copper mine. Following the failure of KCI negotiations with financial institutions to extend loans, the state came to the rescue. Sarcheshmeh copper mine was nationalized in 1972, and its affairs were transferred to a state-owned company named SCMKC. Its name later changed to NICICO. The well-known Iranian technocrat Reza Niazmand was appointed to be the first managing director of the company. SCMKC reached an agreement with the US copper mining giant Anaconda to act as consultant for the mine. The state pushed for accelerated progress, with a detailed plan and sufficient investment arranged for the project to be completed in four years.Footnote 83

The rapid expansion of the mining industry in Kerman province, including coal mines in Zarand and the copper mine in Sarcheshmeh, intensified the possibility of a labor shortage in the agricultural sector.Footnote 84 The company was driven to importing labor from outside Kerman province, from such places as Azerbaijan and Khuzestan. Workers from Khuzestan brought significant experience, gained from establishing and maintaining one of the largest oil refineries in the world, the Abadan refinery, elevating their status as precious skilled workers.Footnote 85 The company was obliged to import workers from other countries as well. Korea, the Philippines, Pakistan, and Bangladesh became the main sources of skilled foreign labor, recruited through a US employment agency.Footnote 86 Despite importing workers from outside the region, the company continued to focus on training local laborers, as there was a higher turnover among the nonlocal employees.Footnote 87

With project development, numbers in the workforce increased. At the end of 1973, the company had employed 46 foreign experts, 75 Iranian staff, and 561 laborers.Footnote 88 The total number of employees increased to 1,310 in 1974, of whom 980 were laborers, 261 Iranian technical staff, and 69 foreign experts.Footnote 89 In the following year, 1975, the number of employees grew to 1,264 laborers, 534 Iranian staff, and 590 foreign experts (Table 1). The total number of employees rose to 2,655 by 1980.

Table 1: Numbers in the Labour Force at the Sarcheshmeh Copper Mine

Source: Sarcheshmeh Copper Mine Annual Report 1973 & 1974

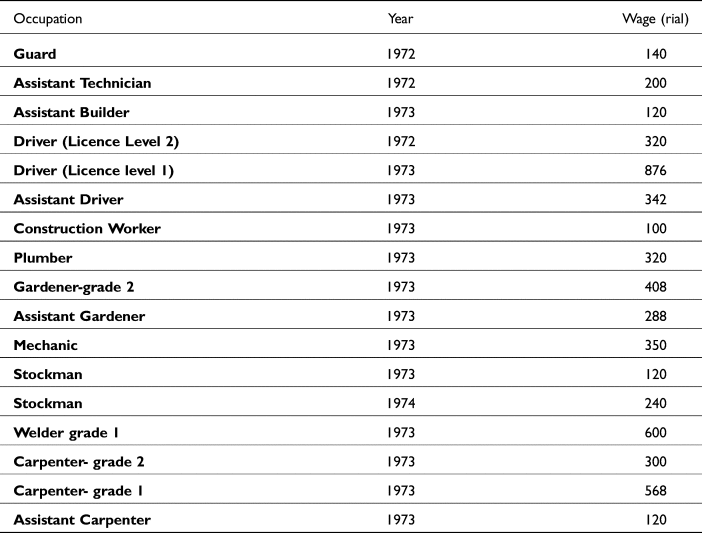

Paternalism developed unevenly across industrial units. It was seen in only 340 enterprises, 5 percent of total companies, in Iran in 1973.Footnote 90 SCMKC, as a state company, gave special consideration to the workforce and promoted KCI's paternalist view. The company paid a minimum wage of 120 rials per day to the unskilled workers in 1973 (Table 2). That was close to the 140 rials paid daily to Iranian oil workers. The difference was that the mine was still being established and not yet operational, whereas the National Iranian Oil Company was well established as a wealthy company.Footnote 91

Table 2: Sample of Workers' Daily Wages at NICICO

Source: Houman Resource Records at NICICO

In addition, SCMKC provided welfare benefits of different kinds, including housing, education, health care, and food. Amenities were established, including a cinema, club, and sports complex in a new town, constructed close to the mine to accommodate 10,000 people, including laborers. The company provided further bonuses such as free flights to Tehran for staff on its own light aircraft.Footnote 92

SCMKC decided to train younger local workers in different fields to prepare them for the wider labor market. A number of courses were promoted to the villagers, and they were encouraged to send their younger children to attend the programs. Among the applicants were teenage girls from different villages, including sixteen girls from Pariz who participated in programs that taught the English language as well office tasks. The company facilitated their everyday transportation to and from Pariz to the mine. The program promised a good future for the girls. Yet they and their families were under social pressure from the local patriarchal culture, which dictated that working outside the home was not acceptable for girls, especially in a workplace with unknown men. The locals called the girls dokhtaran-e maʻdani (the mine girls) to differentiate them from other girls, applying social pressure.Footnote 93 However, one girl, now retired from the Sarcheshmeh copper mine, stated that “we were pleased to go to the mine, because they treated us respectfully at the training center, and we were called ‘Miss.’”Footnote 94

SCMKC's paternalism was influenced by global conditions as well. This was the time of expansion of the welfare state in Europe, based on Keynesian economic theory, partly due to the growth of communism as a threat to the Western bloc. Socialism became the center of thought, leading to newly defined state principles and a series of welfare policies launched to protect citizens against unforeseen unemployment and illness, as well as aging. Living standards improved for the vast majority of people in the Western bloc, including the working class, now identified as the strategic force resisting capitalism.

Socialist movements, founded on class conflicts and the power of the working class, expanded in Latin America, greatly inspiring people in the Global South, including Iran. The emancipatory discourse of socialism opened new horizons for Iranians ruled by an authoritarian regime that had close attachments to the West. Moreover, the Soviet Union, epicenter of world communism and Iran's neighbor to the north, had considerable influence. The shah was alarmed by the penetration of socialism, empowering leftist forces in Iran. Therefore he strategically accorded importance to the welfare of the working classes, aimed at reducing class conflict.

The rapid growth of the price of oil in the late 1960s and 1970s and the resulting enormous source of income enabled the state to introduce welfare policies targeting the working class. However, these social programs were not evenly placed, as the growth in renumeration, social position, and job security expanded particularly in the large new industries of oil, petrochemicals, steel, and industrial manufacturing.Footnote 95 This stemmed from Iran's industrialization strategy, which was driven by import substitution. This was a labor market discrete from that of an export-oriented industrialization. The latter relied predominantly on low labor costs to keep final prices down, making it competitive on the international market, whereas the former targeted the domestic market to make the country independent from outside market forces in relation to a particular commodity.Footnote 96 Import substitution enabled specific industries to monopolize the domestic market without strong competition, improving their financial performance. Import substitution and state protectionism therefore were less concerned with a reduction in labor costs, leading companies to offer enhanced welfare policies. During the 1960s and 1970s, as Iran's rapid industrial growth increased the scarcity of skilled labor, this was necessary to attract the most skilled workers.Footnote 97 Welfare policy benefited a third of the total paid workforce in Iran, who received five times more income than workers in other industries and sectors.Footnote 98 The remaining two-thirds were semi- and unskilled workers in the mining industry, construction, and small industries and services in urban areas.

SCMKC was one of those companies that developed a welfare policy for the workforce. The chosen policy was not merely determined by an import substitution strategy, as the primary financial projection showed a high return for the company in its operational stage. This projected a sufficient level of profitability to recoup the initial high investment in infrastructural welfare development, such as housing. Welfare measures also were necessary due to the remote geographical location of the mine and its harsh environment, making it an unattractive place to work, especially to those coming from outside the region. This was exacerbated by the years of rapid industrial growth in the 1960s and 1970s when the country was faced with a paucity of professional workers, including skilled laborers, technicians, and experts. The presence of American and European workers also drove the managing director to pay more attention to improving social services. As Reza Niazmand stated, “I planned to construct a modern copper complex in all aspects, from technology to welfare facilities. We had to run highly developed social services to persuade the workforce to stay at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine.”Footnote 99, Finally, according to Niazmand, the presence of Americans greatly influenced the design of social policy and the establishment of welfare benefits at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine.Footnote 100

Sarcheshmeh Copper Mine's Workers and the 1979 Revolution

Rapid economic growth and industrial expansion increased the number of commercial and industrial units in Iran. This had an impact on the demographics of the labor market and the size of the paid labor force. In 1940, 70,000 workers worked in large workshops with ten or more employees. This increased to 1.25 million by 1976. Of those 1.25 million, 750,000 were employed in industry and mining, and 500,000 were working in the construction sector.Footnote 101

The expansion of the working class was a double-edged sword for the authority. As a main contributor to industrial development it could be fashioned into a social force to petition for its class interests, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s when socialist movements flourished in Iranian intellectual discourse. It was feared revolutionary ideas would spread among the working class, generating a threat against the political system. As a result, alongside strict suppression, as has been discussed, the state employed a softer approach to maintaining worker satisfaction and preventing political activism. Social phenomena compelled the state to improve workers’ living and working conditions, with particular attention to the industrial working class. One of the six articles of the 1963 White Revolution addressed workers, with an ordinance that company shares must be sold to workers.Footnote 102 Again, this development plan was unable to distribute benefits and facilities equally among workers in different sectors. From 1963 to 1973, an average growth of 2.9 percent in wages is seen in the industrial and transport sectors. But the wages of workers in the leather industry rose by just 0.5 percent annually, whereas was a 9.8 percent increase for workers in the chemical industries.Footnote 103

This disparity between workers’ material conditions could determine political orientation. In fact, the persistent inequalities inside the working class reduced coherent resistance to the political system, a factor during the unrest leading up to the Iranian Revolution in January 1979. Although it was expected that the workers would protest for political liberties along with the other social classes, according to Ashraf that assumption did not entirely come to fruition; industrial workers belatedly joined the protest, and then focused mainly on their union claims rather than political demands.Footnote 104 Parsa argues that the workers were late to join the revolutionaries because of the suppressive regime that reduced workers’ solidarity.Footnote 105 That claim needs further scrutiny as the suppressive conditions were not limited to the working class; other social classes lived under the suppressive state as well.

The protests were started by the traditional and modern middle class in early 1978. The rise of Iranian state income due to the oil boom in the 1970s caused the shah to ignore expert opinion and the existing developmental plan. He asked that the pace of development be increased by injecting more petrol money. This ambitious, accelerated development precipitated high economic inflation, leading to a rise in industrial workers’ grievances. The street unrest and political protests beginning in March 1978 shaped a space for workers to strike and voice their economic demands.Footnote 106 Workers of the Azmayesh factory went on strike because 300 workers were made redundant.Footnote 107

The economic orientation of workers’ demands continued until the final stage of the revolution, from October 1978 onward, when the state lost political stability. Industrial workers did not substantially support the revolutionaries until the fall of 1978, when the revolutionary spirit spread across the country and the state was confronted by a unified movement consisting of people from different social classes and social strata, including industrial workers.Footnote 108 To their economic demands for an increase in wages, industrial workers added political demands, such as the cancellation of martial law.Footnote 109 However, as described by Ashraf, although some intellectuals have exaggerated the importance of industrial workers as a progressive force in the revolution, there is no doubt about the relatively limited participation of Iran's working class.Footnote 110 During the last months of the revolution (in December 1978 and January 1979) 109 of 773 large industrial units, or only 14 percent, went on strike to demand better wages and economic concessions.Footnote 111

The literature on the 1979 revolution has mostly ignored the diversity of workers’ claims during that time and identified their demands as a revolutionary act. This negligence has been primarily generated by leftist scholars who present the workers as a revolutionary class. In his renowned book, Iran between Two Revolutions, Abrahamian narrates the workers’ collective actions and claims during the course of the 1979 revolution, but does not consider the nature of the demands, instead identifying them as a political move against the shah.Footnote 112 Abrahamian presents the workers’ strikes without describing the cause of these protests, or the disparities experienced by the workers. This oversight has limited understanding of the class dynamics of the Iranian working class and its movement.

Contrary to this narrative representing Iranian industrial workers as a revolutionary working class, the newly trained industrial workers at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine had a different relationship with the 1979 revolution. As a radical movement mushroomed across most Iranian cities, the mine remained peaceful; there was no major disruption in the workplace.Footnote 113 The Islamists and the leftists had some minor skirmishes, but the vast majority of employees, workers, and technical staff were involved in their daily work. Only on rare occasions were political leaflets seen in the workplace. The intelligence service (SAVAK) maintained a minimum presence at the mine compared with their ubiquity at state-owned heavy industries, as according to company statutes it was not operating under state regulations.Footnote 114 The depoliticized atmosphere continued until fall 1978, when the waves of revolution eventually reached Sarcheshmeh. Then, on October 9, the Sarcheshmeh copper mine employees went on strike, demanding pay raises, housing, and insurance.Footnote 115 Later laborers and technical staff had different responses to the movement. Whereas the technical staff for the most part joined the revolution, voicing their political demands, laborers evinced little interest in standing against the state. In fact, the protests were started by the technical staff who represented a modern, educated middle class.Footnote 116 The laborers were not always just bystanders, sometimes displaying their disagreement with their fellow employees. During a strike by the technical staff, a group of laborers attacked them, shouting, “You intend to make us wretched. You make us poor.”Footnote 117 This is an example or workers acting in line with their class interests. When students wished to join the workers to strike and distribute leaflets, the workers tore up the leaflets and threw the students out, chanting, “Long live the Shah.”Footnote 118 The workers wished to separate their collective actions from the political movement. This also was seen among oil workers, the progressive labor force in the Iran revolution, when they insisted that their strikes were based on union claims rather than political demands before October 1978.Footnote 119

The Sarcheshmeh copper mine workers’ desire to preserve the status quo resulted from their satisfaction with their improving economic circumstances due to the company's steps to improve employee welfare and thereby transform class struggle into a form of class compromise. Wright divides class compromise into two types, positive and negative, to develop his argument on advancing anti-capitalism.Footnote 120 Contrary to the negative approach to class compromise found in Marxist literature, Wright believes class struggle can play a constructive role in making the transition less harmful. He first explains four strategies to apply against capitalism: smashing, taming, escaping, and eroding it. Wright considers taming capitalism a wise strategy in the early stages of anti-capitalism, in which class struggle is converted to class compromise, leading to less damage from capitalism.Footnote 121 The mechanism of conversion relies on the two sources of working-class power: structural power and associational power, as discussed previously. Wright states that the associational power of workers can convert the class struggle into a positive class compromise, in which both sides of the conflict can benefit from the results. One side's success does not cause the other side's loss. This generates a sustained relationship. Conversely, a negative class compromise due to a scarcity of organizational power among the working class leads to one side's win and the other side's loss. According to Wright, the negative class compromise cannot reasonably secure the interests of both sides and results in a fragile, unsustainable relationship between capitalist and worker.

At the Sarcheshmeh copper mine, the workers’ position against the revolutionaries was a reflection of this transformation of the class struggle into a form of class compromise. This was not what Wright describes as positive class compromise, as it did not originate from the enhanced organizational power of the working class, but rather from the structural power of the workers, which increased due to rapid industrialization and a labor shortage. This led to the wealthy company's augmented welfare policy and sufficient wages to attract the needed labor force. This was abetted by the Iranian state's paternalistic manner of managing social welfare, which led to improvement of the living and working conditions of the poor rural workers who came to work at the mine. These interrelated elements contributed to formation of the reluctant revolutionary industrial workers at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine, as displayed during the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

In the last month of the revolution, the mine and town were disordered. The expatriate employees, mostly Americans and British, received anonymous leaflets inciting them to go home.Footnote 122 Later, an American, Martin, was killed in Kerman.Footnote 123 Anti-American slogans such as “Yankee Go Home” were written on walls in the town and at the mine site.Footnote 124 The managing director, Mehdi Zarghamee, recognized that the conditions were unsafe and out of control. He ordered all foreigners to evacuate the site and return to their homes.Footnote 125 The mine and town were hurriedly evacuated by all foreigners. They left the town scrawling messages on the walls saying, “We'll Be Back,” apparently a response to the “Yankee Go Home” slogans.Footnote 126 Many possessions and even pets were left behind. Four buses were hired to take the foreigners to Bandar Abbas Airport where they boarded an aircraft chartered to take them to Bahrain, from where each headed to their chosen destinations, the vast majority returning to the United States.

Conclusion

This article has delineated global and local conditions to illustrate the role of the state, the nature of capital, international contributors, and traditional labor relations in the approach of industrial companies to their workers. It also has examined the impact of these factors on the making of reluctant revolutionary industrial workers out of worker-peasants during the establishment of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine.

The undeveloped structure of the mining industry in Iran made it part of the labor-intensive business sector. This led private companies such as KMC to rely on surplus value generated by cheap labor. The company used various means, including influential statesmen whose economic interests were tied up with private businesses, to breach the labor law; maintain a lack of awareness about labor rights among the workers; and continue traditional labor relations to dominate employees and keep labor costs down. However, KMC's narrow vision of labor relations and working conditions resulted in a poorly functioning labor system, keeping the laborer a worker-peasant rather than an industrial worker during the early stages of exploration.

The global turn to a postcolonial order and growth of working-class models as a progressive political force compelled international companies to deploy paternalism in labor relations in the Global South, as Selection Trust did at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine. This was tied to the expansion of socialist movements across the world, which were a major threat to the West and its allies, including Iran. The Iranian state instituted a plan to improve workers’ living and working conditions to minimize the likelihood of class conflict. The nationalization of the Sarcheshmeh copper mine was the next stage; NICICO adopted a developed welfare policy. The state's capital from rising oil income and a forecast of a promising revenue from the mining company led to significant investment in a developed welfare structure. The remoteness of Sarcheshmeh and its rough environment, along with the presence of Anaconda and American technical and managerial staff also pushed NICICO to care more for the well-being of its workforce.

Welfare improvement was not merely determined by top-down programs; grassroot components also contributed to the process. In the absence of workers’ organizational power and few collective actions, employees used alternative means, including petitioning, to make their demands. Moreover, Iran's growing economy and active industrialization created a tight labor market in the 1970s, which led to rising structural power of the working class and an enhanced bargaining position. Local workers, particularly those who owned land, also benefited as the company had to offer better conditions to convince them to sell their land.

The combined interaction of elements from above and below introduced a developed paternalist program for laborers at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine. This, along with the laborers’ poor background, led to the workers to take a cautious stance during the widespread street protests that led to Iran's 1979 revolution. While the mob protests disquieted the country in 1978–1979, the workers at Sarcheshmeh copper mine were intent on maintaining the status quo. As engineers, technicians, and office staff showed sympathy for the revolutionaries, the industrial workers were less keen to join the protest against the shah, and on a few occasions even stood against the revolutionaries. In fact, this was a revolution of engineers, technicians, and office staff, rather than industrial workers, at the Sarcheshmeh copper mine.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my gratitude to Touraj Atabaki and Ali A. Saʿidi for their valuable comments during the course of this research.