Like many constitutional democracies,Footnote 1 at the time of its framing, the Indian Constitution provided for members of the higher judiciary to be appointed by the executive.Footnote 2 The Constituent Assembly specifically rejected a proposal which required the concurrence of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court for appointments to higher judiciary.Footnote 3 However, unlike any other constitutional democracy, the executive in India has been effectively relegated to the role of a passive participant in the process of judicial appointments through a series of judicial decisions in 1993,Footnote 4 1998,Footnote 5 and 2015.Footnote 6 In 1993, the Supreme Court of India created the collegium model of judicial appointments wherein the executive was divested from a determinative role in appointment of judges.Footnote 7 From 1993 to 1998, the collegium consisted of the Chief Justice and two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court while appointing judges to both the Supreme Court and the High Courts.Footnote 8 Since October 1998, the collegium consists of the Chief Justice and four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court when appointing judges to the Supreme Court.Footnote 9 When appointing judges to the High Courts, it consists of the Chief Justice and two senior-most judges.Footnote 10 The appointment process is initiated by the collegium and the most the executive can do is request for a reconsideration which the collegium has the authority to ignore. The executive does not have the power to overrule the recommendation of the collegium.Footnote 11

While there has been considerable scrutiny of the collegium's constitutionality,Footnote 12 there has been limited research on its empirical implications. Chandrachud,Footnote 13 Tripathy and Rai,Footnote 14 and KumarFootnote 15 have looked into the collegium's policy on the tenure of Supreme Court judges. Chandra, Hubbard, and KalantryFootnote 16 have analysed the collegium's impact on judicial diversity in the Supreme Court on parameters such as religion, caste, and gender. Tripathy and DhaneeFootnote 17 have examined how the collegium has impacted professional and regional diversity in the Supreme Court.

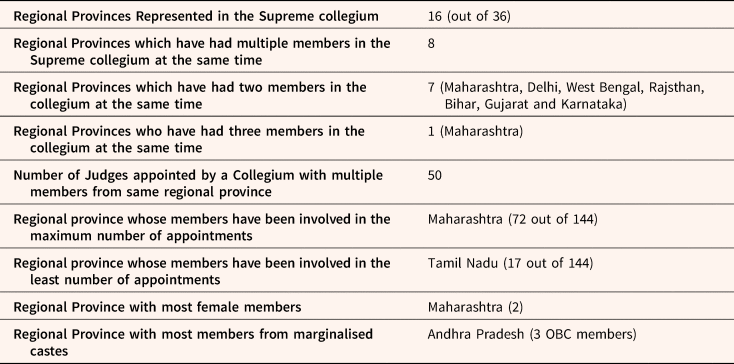

However, there has been no attempt to examine diversity in the collegium. Also, no attention has been paid to appointment by specific collegiums over a period of time. Thus, we have no meaningful understanding of how the collegium's power has been distributed amongst its member in terms of their social and professional background. This is important because not all collegium members have wielded equal power.

It is important to note that unlike some other jurisdictions,Footnote 18 there is no mandate regarding proportionality of representation in relation to the higher judiciary in India. This is an oddity in the Indian context where affirmative action policies are in place in relation to all other public institutions.Footnote 19 Consequentially, there is also no rule regarding the representative composition of the collegium. The consequence of the absence of any mandate in this respect can be seen in the skewed history of collegium's composition which has been highlighted in this article.

The findings in this article reveal that the collegium has been a site of marginalisation for female judges and judges of marginalised caste communities in terms of representation and influence. While caste representation has improved in the last couple of years, gender continues to be an significant factor of exclusion. It shows that select regional provinces have had dominant representation in the collegium and have also exercised disproportionate influence in judicial appointments. It also highlights how judges from certain professional background have been pushed into irrelevance in terms of judicial leadership.

The Invisible Collegium

Traditionally, Chief Justices have been the focal point in academic scholarship while analysing patterns of appointments and composition of the court. Before the creation of the collegium, Gadbois Jr. looked into the composition of the court under various Chief Justices from 1950 to 1989.Footnote 20 More recently, Chandrachud has looked into the issues of regional representation and tenure of judges in the Supreme Court under different Chief Justices.Footnote 21 However, the constitutional reality of the collegium means that that we ought to acknowledge the influence of other members of the collegium while assessing the selection policies prevalent in the higher judiciary. Imagining the Chief Justice as a singular power centre without taking into account the influence of other members of the collegium is legally suspect and also factually inaccurate.

Legally, it is highly implausible for the Chief Justice to be able to recommend an appointment without the concurrence of the other members in the collegium. The formation of the collegium was based on the premise that the Chief Justice has to form his opinion after taking into account the views of his colleagues and that he is not authorised to form an individual opinion.Footnote 22 The Supreme Court has clearly conceptualised a situation where the recommendation of the Chief Justice will not be binding of the government if the recommendation is opposed by the other members of the collegium.Footnote 23 The Memorandum of ProcedureFootnote 24 which regulates the process of appointment of judges in the Supreme Court and the High Courts also makes the opinion of the collegium members an indispensable part of any recommendation. Firstly, it clearly states that the opinion of the Chief Justice shall be formed after consultation with other members of the collegium. Secondly, it mandates for the Chief Justice to share with the government the written opinion of the collegium members.

At least two incidents in the recent past bear out the influence of the other collegium members in the appointment process of judges in the Supreme Court. Justice SA Bobde, despite being the Chief Justice over fifteen months, was not able to appoint a single judge to Supreme Court although there were several vacancies during his term. At the time of his retirement, the court was six judges short of its sanctioned strength. This situation seems to have its roots in the lack of consensus amongst the members in the collegium.Footnote 25 A more controversial incident took place in 2019. The collegium headed by Justice Ranjan Gogoi in which Justice Madan B Lokur was the second puisne member, resolved on 12 December 2018 to recommend the names of Delhi High Court Chief Justice Rajendra Menon and Rajasthan High Court Chief Justice Pradeep Nandrajog for appointment as judges in the Supreme Court.Footnote 26 The collegium's composition changed when Justice Lokur retired on 30 December 2018 and Justice Arun Mishra became a member. Within two weeks of Justice Lokur's retirement, the reconstituted collegium decided to override the decisions taken by the previous collegium and resolved to recommend two other names for appointment to the Supreme Court (Justice Dinesh Maheshwari, Chief Justice of the Karnataka High Court, and Justice Sanjiv Khanna from the Delhi High Court).Footnote 27 This decision was particularly controversial as Justice Khanna was appointed superseding other senior judges in various High Courts.Footnote 28 It is doubtful if such a reversal of decision would have been possible without a change in the composition of the collegium.

The Bifurcated Collegium

Whenever we talk about the collegium, it is important to remember that there isn't a single collegium but two collegiums exercising power in different contexts and with partially overlapping membership. For appointing judges to the Supreme Court of India, the collegium consists of the Chief Justice and four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court (herein after Supreme collegium).Footnote 29 The Supreme collegium also decides on the transfer of judges from one High Court to another.

The collegium for appointing judges to the High Courts includes the Chief Justice and two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court (hereinafter ‘High collegium’).Footnote 30 The High collegium also decides on the appointment of Chief Justices in various High Courts. However, when it comes to transfer of Chief Justices from one High Court to another, the decision is taken by the Supreme collegium.

Thus, while the Chief Justice and the two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court are members in both the collegiums, the third and fourth puisne judges of the Supreme Court are members only in the Supreme collegium. The Supreme collegium exercises its power of appointment more rarely than the High collegium. During a period of more than three years from 3 October 2017 to 2 March 2021, the Supreme collegium recommended the appointment of only 17 judges in the Supreme Court.Footnote 31 During the same time, the High collegium recommended the appointment of 342 judges in various High Courts.Footnote 32

In terms of membership, the High collegium is more elusive than the Supreme collegium for obvious reasons. It is more difficult to reach the required level of seniority to be eligible for the membership of the High collegium. There have been many judges who became members of the Supreme collegium but not could not acquire the membership of High collegium. For example, Justice AK Patnaik from the regional province of Odisha became a member of the Supreme collegium but by the time of his retirement, he was only the third puisne judge in the Supreme Court and was never a member of the High collegium.

While the Supreme collegium exercises power infrequently, it may be argued that its authority to shape the composition of the highest court of the land is more critical than that of the High collegium. On the other hand, the High collegium's control over the composition of the provincial High Courts is especially crucial when more than 96 per cent of the Supreme Court judges are appointed from the pool of High Court judges.Footnote 33 In a very direct way, the High collegium regulates the range of choices available to the Supreme collegium. In its crudest manifestation, this may involve the High collegium rejecting the candidature of a person for High Court judgeship. More subtly, it can reflect in the High collegium delaying the appointment of a person as a High Court judge. As the inter se seniority of High Court judges is an important consideration for the Supreme collegium while appointing judges to the Supreme Court,Footnote 34 delayed appointment to the High Court can make someone's prospects more difficult.Footnote 35

Methodology

Data for this article was collected in two sequential phases. The first phase focused on identifying the composition of Supreme collegiums and High collegiums constituted since 1993. The second phase focused on determining the appointment history of each Supreme collegium. Data was collected primarily from three sources: (1) The Supreme Court website; (2) Responses from the Department of Justice, Government of India to applications filed under the Right to Information Act 2005 and (3) Interviews with former Chief Justices and former members of the collegium. A total of twenty former members of the Supreme collegium were interviewed which included fifteen former members of the High collegium and seven former Chief Justices.

Data on Composition of Collegiums

In the first phase of data collection, the duration and composition of each Supreme collegium and High collegium from 6 October 1993Footnote 36 to 30 September 2021 was identified. The analysis includes all judges who became members of the Supreme collegium or High collegium before 30 September 2021 even though their date of retirement is later than that date.

Unlike any other entity constituted by or under the provisions of the constitution, the composition of the collegium is not publicly notified through the official gazette and is also not available in any official public platform. For example, the website of the Government of India contains details of the Council of Ministers.Footnote 37 On the other hand, the official website of the Supreme Court does not provide any details of the current or past members of the collegium. Between 2017 and 2019, the collegium resolutions published in the Supreme Court website contained the names of the collegium members. However, since October 2019, the resolutions do not mention the collegium members.Footnote 38 As a consequence, there is no clear information available about the composition of the collegium on a given date in the past.

Thus, for ascertaining the composition and duration of each Supreme collegium and High collegium, reliance was placed on the author's dataset on the tenure of Supreme Court judgesFootnote 39 which is created from the information available in the Supreme Court website. Findings were verified through interviews with former Chief Justices and former members of the collegium. As membership of the collegium is based on seniority, the very first collegium was identified based on the seniority amongst judges who were in office immediately after the Supreme Court's decision on 6 October 1993 which established the collegium. The second collegium was identified based on the seniority amongst the sitting judges in the Supreme Court on the date on which a member of the first collegium retired/died/resigned. To illustrate, the first collegium had the following three members; Justice MN Venkatachalliah, Justice Ratnavel Pandian and Justice AM Ahmadi. The first member to retire from amongst them was Justice Pandian on 12 March 1994. On the date of Justice Pandian's retirement, the senior-most judge in the Supreme Court was Justice Kuldip Singh who became a member of collegium on 13 March 1994. This exercise was repeated sequentially for each collegium to determine the chain of succession.

Essentially, membership of the collegium is not based on a simple chronological list of seniority but on having necessary seniority on the specific dates when a vacancy arises in the collegium. For example, four judges were appointed to the Supreme Court on the same date of 9 December 1998 as per the following sequence of seniority; (1) MB Shah, (2) DP Mohapatra, (3) UC Bannerjee and (4) RC Lahoti. While Justices Lahoti and Shah became members of the Supreme collegium for 1088 and 279 days respectively, Justices Mohapatra and Bannerjee never became members of the collegium. Whenever there was a vacancy in the collegium during the tenure of Justice Mohapatra or Justice Bannerjee, they were not amongst the four senior-most judges in the court. For example, when a vacancy arose in the collegium due to the retirement of Justice SP Bharuchha on 5 May 2002, Justice Mohapatra was the seventh senior-most judge the Supreme Court. By the time the next vacancy arose due to the retirement of Justice BN Kipral on 7 November 2002, Justice Mohapatra had already retired on 2 August 2002. On 7 November 2002, while Justice Banerjee was still in office (he retired ten days later on 17 November 2002), he was the seventh senior-most judge in the Supreme Court.

Seniority is based on the date of appointment in the Supreme Court. When judges are appointed on the same date, seniority is based on the inter se High Court seniority amongst the judges. With an overwhelming majority of judges in the Supreme Court being appointed from the pool of High Court judges,Footnote 40 High Court seniority is determined with reference to the date on which a person is appointed as a judge in any of the High Courts. For example, both Justices Dipak Misra and Jasti Chelameswar were appointed to the Supreme Court on 10 October 2011. However, as Justice Misra was appointed as a High Court judge before Justice Chelameswar,Footnote 41 he had inter se seniority. This also meant that when Justice Jagdish Singh Kehar retired on 27 August 2017, Justice Misra succeeded him as the Chief Justice instead of Justice Chelameswar.

In the limited number of instances where judges appointed directly from the BarFootnote 42 share the same date of appointment with judges appointed from the pool of High Court judges, it has been a conventional rule for judges appointed for the pool of High Court judges to have seniority. While Justices AM Ahmadi and Kuldip Singh were both appointed on 14 December 1988, Justice Ahmadi was designated the senior judge as Justice Singh was appointed directly from the Bar. This meant that Justice Ahmadi became the Chief Justice upon the retirement of Justice MN Venkatachaliah. This conventional rule has held true over the years in the appointments of Justices RF Nariman,Footnote 43 UU Lalit,Footnote 44 L Nageshwar RaoFootnote 45 and PS Narsimha.Footnote 46

Data on Appointments by Collegiums

In the second phase of data collection, the recommending Supreme collegium for each Supreme Court appointee from 6 October 1993 to 30 September 2021 was identified. The recommending Supreme collegium refers to the collegium which for the first time recommended the name of a person for appointment as a judge in the Supreme Court. An appointment ought to be attributed to the collegium which recommends the judge's name as it is not always the same collegium under which the judge takes oath of office. While the date on which a judge takes oath of office is publicly available, the date on which a candidate was recommended for appointment is not openly available.

For identifying the recommending Supreme collegium for judges appointed after 6 October 1993 and before 30 September 2021, reliance was placed on interviews with former Chief Justices and former collegium members. Information gathered from the interviews was corroborated with the responses of the Department of Justice, Government of India to applications filed under the Right to Information Act 2005.

This exercise resulted in identification of twenty-two judges who were recommended for appointment by one collegium but took oath of office under another collegium. For example, when Justice Cyriac Joseph took oath of office on 7 July 2008, the Supreme collegium had the following members: Justices KG Balakrishan, BN Agrawal, Ashok Bhan, Arijit Pasayat, and SB Sinha. However, the collegium which recommended Justice Joseph for appointment had Justice HK Sema as its member and not Justice SB Sinha.Footnote 47 In this case, the collegium which had Justice Sema as its member is attributed as the recommending Supreme collegium.

In relation to five judges, the Chief Justice under whom they took the oath of office was not the Chief Justice when their name was recommended. For example, Justice AK Mathur took the oath of office when Justice RC Lahoti was the Chief Justice but his name was recommended by the collegium in which Justice VN Khare was the Chief Justice.Footnote 48

Framework of Analysis

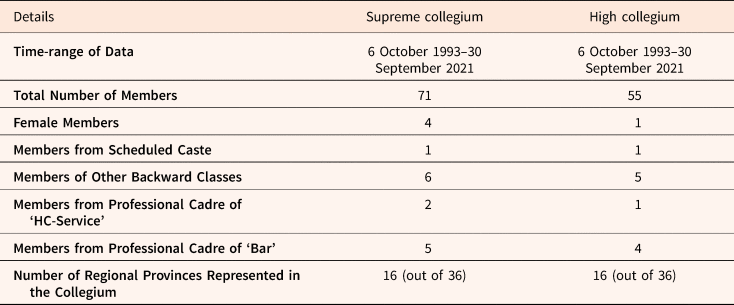

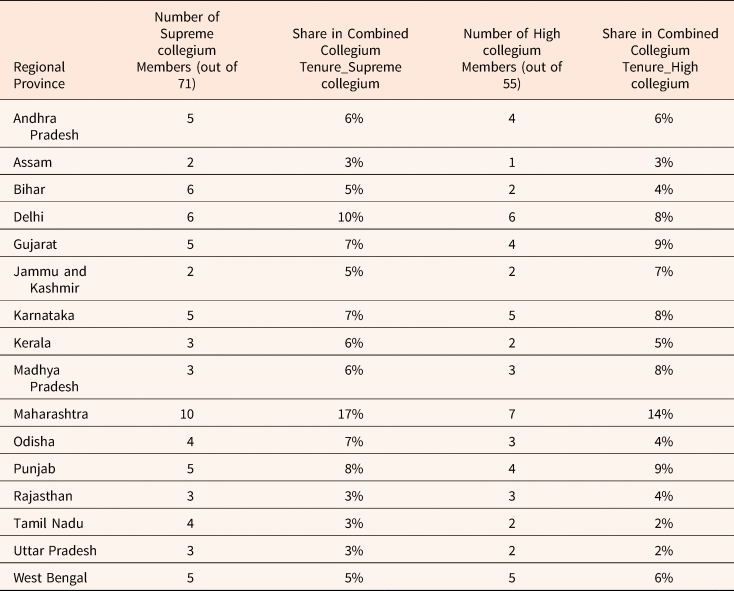

The analysis in this article has two layers. Firstly, diversity of presence in Supreme collegium and High collegium over the last three decades has been scrutinised in terms of gender, caste, region and professional background of collegium members. This analysis includes 71 members of the Supreme collegium and 55 members of the High collegium out of a total 165 judges who have held office in the Supreme Court during this period.

Secondly, the influence of Supreme collegium members has been measured in terms of the number and nature of appointments to the Supreme Court that they have been involved in. This exercise enables us to assess if the collegium's authority has been evenly distributed amongst its members or if it has been concentrated in the hands of few. In this context also, attention is paid to the gender, caste, region and professional background of the collegium members.

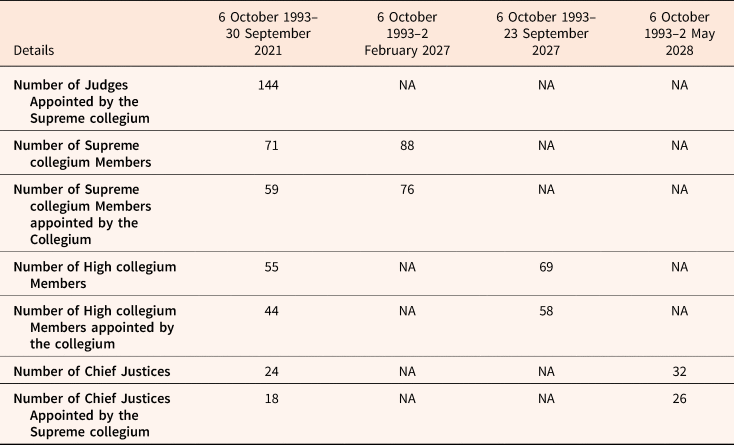

To classify nature of appointees, it has been examined if an appointee was a future Chief Justice or future member of either the Supreme collegium or High collegium. Appointments of future Chief Justices or future members of either collegium are more influential as they have a direct bearing on the judicial leadership of the country. For identifying future Chief Justices and members of the Supreme and High collegium, the analysis includes all such judge who were appointed before 30 September 2021 but are scheduled to assume membership of either of the collegiums or scheduled to become the Chief Justice after 30 September 2021. For example, Justice BV Nagarathna was appointed to the Supreme Court on 31 August 2021 and her name was recommended by the collegium comprising of Justices NV Ramana, UU Lalit, AM Khanwilkar, DY Chandrachud and L Nageshwar Rao. She is due to become a member of the Supreme collegium in May 2025 after the retirement of Justice Abhay Oka. While analysing the diversity of presence in the Supreme collegium, Justice Nagarathna has not been included as her membership of the Supreme collegium is due to begin after 30 September 2021. However, while analysing the appointments made by Justices Ramana, Lalit, Khanwilkar, Chandrachud, and Rao, Justice Nagarathna has been counted as a future Supreme collegium member. The last dates for this counting is 9 February 2027 (Supreme collegium) and 23 September 2027 (High collegium). After these respective dates, there will not be enough judges left out of those appointed before the cut-off date for this article (30 September 2021) in order to constitute the Supreme collegium and the High collegium. For example, after the retirement of Justice Vikram Nath on 23 September 2027, there will only be two of the current judges remaining in office (Justices BV Nagarathna and PS Narsimha) and the High collegium at the time will necessarily include a judge appointed after 30 September 2021. The last date for Chief Justices is 2 May 2028.

As the internal deliberations of the collegium are held in secret, it is impossible to assess the actual influence of members inside the collegium. It is not possible to determine if one collegium member played a greater role in the appointment of a particular judge in terms of suggesting the name or in terms of convincing other members. Nevertheless, as the possibility of collegium appointing a judges against the wishes of any member is fairly remote,Footnote 49 it is safe to assume that each member of the collegium had a positive agreement in relation to the candidate recommended by the collegium. Thus, all members of a recommending collegium have been presumed to have had an equal contribution in the appointment of candidates recommended by them. This proposition is supported by former members of the collegium who were interviewed for this article.Footnote 50 This is also corroborated by Justice Ranjan Gogoi's account of the inability of Justice TS Thakur to ensure appointments in the months before his retirement as the Chief Justice of India due to the non-cooperation of Justices Dipak Misra and Jagdish Khehar.Footnote 51 However, Chief Justices play a significant role in in terms of initiating the recommendation of a candidate and consequentially, for judges who assumed the office of Chief Justice, the number of appointments they were involved in as a Chief Justice has been highlighted.

There are instances of more than one member from the same caste category or region being a member of the collegium at the same time. In terms of examining the influence of the caste category or the region, the frequency of such instances has been considered.

This influence analysis covers all appointments attributed to the collegium from 6 October 1993 to 30 September 2021. A total of 145 judges were appointed between 6 October 1993 and 30 September 2021. However, the appointment of Justice Sujata V Manohar on 8 November 1994 has not been attributed to the collegium. Her name was recommended for appointment by Chief Justice MH Kania (13 December 1991–17 November 1992) before the collegium system came into existence.Footnote 52 The recommendation was subsequently reiterated by Justice MN Venkatachaliah when he headed the collegium from 6 October 1993 to 24 October 1994.Footnote 53

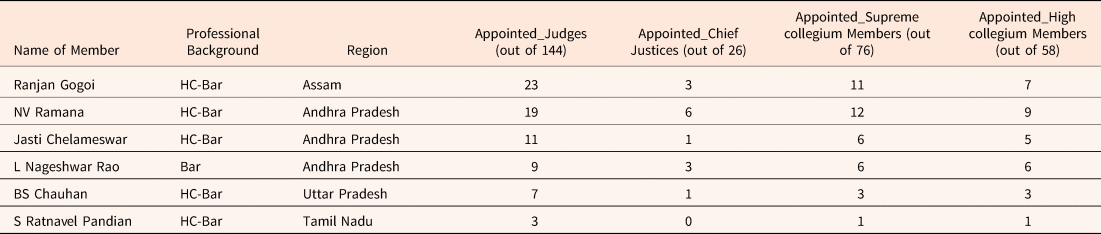

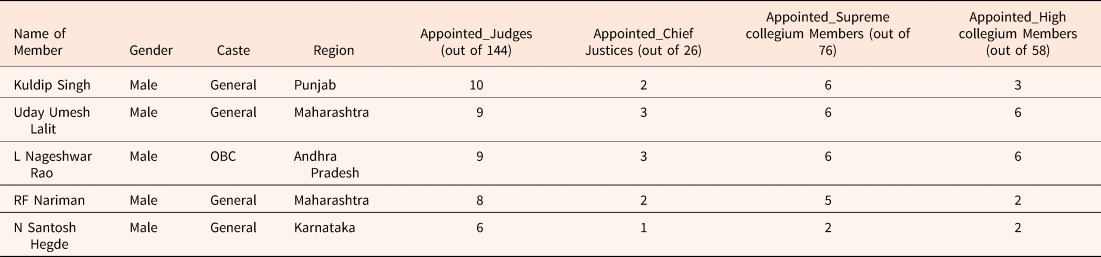

Table 1. Overview of the Data for Analysing Influence of Collegium MembersFootnote 54

Table 2. Overview of Collegium MembershipFootnote 55

Gender

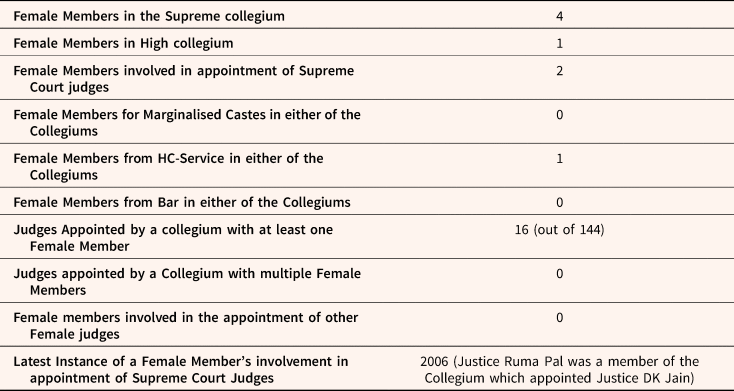

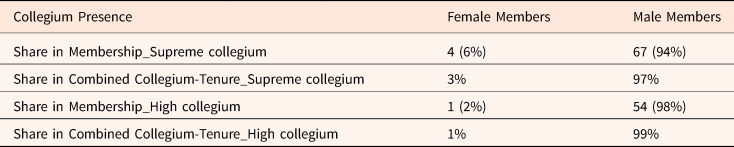

As demonstrated in Table 3 above, women are not adequately represented in the Supreme Court. Between 1950 and 2021, women have constituted only 4 per cent of judges in the Supreme Court and had only 3 per cent of the tenure-share. Tenure-share is the share of judges in the combined actual tenure of all appointees. None of the eleven female judges appointed to the Supreme Court belong to the Scheduled Caste or the Other Backward Classes.Footnote 57 In the Supreme collegium, the share of female judges in the combined collegium-tenure of all members is 50 per cent less than their share in the overall membership of the collegium (Table 4). Collegium-tenure refers to the amount of time spent by a member in the collegium. This means that even when they become members in the Supreme collegium, female judges spend less time in the collegium compared to their male colleagues.

Table 3. Overview of Female Members in Supreme collegium and High collegiumFootnote 56

Table 4. Gender Representation in Supreme and High collegiumFootnote 58

On average, a male member of the Supreme collegium has had close to 2 per cent share in the combined collegium-tenure of all members. The corresponding number for a female member is less than 1 per cent. On average, the collegium-tenure of male members constitutes 28 per cent of their total tenure as a Supreme Court judge. For female members, its only 16 per cent.

Even these numbers are propped up by the presence of Justice Ruma Pal from the regional province of West Bengal. Without her, the share of female members in the combined collegium-tenure drops to 1 per cent from 3 per cent and the collegium-tenure of female members on an average is reduced to 10 per cent of their total tenure as a Supreme Court judge. Justice Pal also remains the sole female member in the High collegiumFootnote 59 with a share of 1 per cent in the combined collegium-tenure of all members.

Three female judges (Justice Gyan Sudha Mishra from Bihar, Justice Indu Malhotra from Delhi, and Justice Indira Bannerjee from West Bengal) never became members of the Supreme collegium. Out of the three most recently appointed female judges (Justice Bela Trivedi from Gujarat, Justice Hima Kohli from Delhi, and Justice BV Nagarathna from Karnataka were appointed on 31 August 2021 which was just a month prior to the cut-off date for this article), Justice Nagarathna will become a member of the Supreme collegium in May 2025 and a member of the High collegium in June 2026. She is also due to become the first female Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in September 2027.Footnote 60

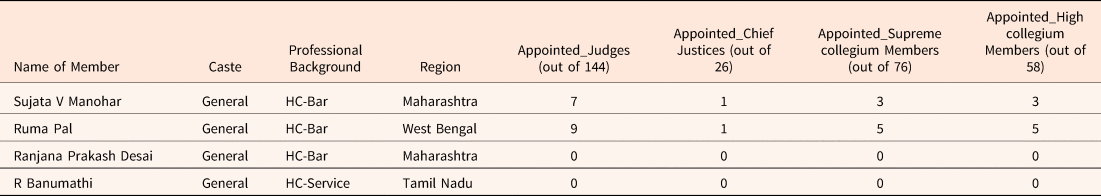

The last time a female member was involved in an appointment was Justice Ruma Pal in 2006. Two female members of the Supreme collegium, (Justice Ranjana Prakash Desai from Maharashtra and Justice R Banumathi from Andhra Pradesh) joined and retired as the junior most member of the collegium and have also not been involved in a single appointment. Justice Sujata Manohar from Maharashtra and Justice Pal have been involved in a total of 16 appointments which constitutes 11 per cent of collegium appointees. Of the four members, only Justice Banumathi came from the cadre of HC-Service and the other three members came from the cadre of HC-Bar.Footnote 61

The involvement of female members in the appointments of future Chief Justices and of future members of Supreme collegium and the High collegium is predictably low considering their limited presence in the collegium (Table 5). The marginalisation of female members is evident from the fact that on an average, a male member is involved in more than twice the number of appointments compared to a female member (ratio of 4:10).

Table 5. Influence of Individual Female Members in Supreme collegiumFootnote 65

A brief summary of gender diversity in the Collegium

Out of the 10 female judges who have been in office between 6 October 1993 and 30 September 2021, four have been members of the Supreme collegium (out of 71 members) and one (Justice BV Nagarathna) is due to become a member in 2025. Thus, 32 years after the inception of the collegium, female members will account for only 6 per cent of all the Supreme collegium members (5 out of 88). After Justice Ruma Pal, Justice Nagarathna will be only the second female judge to become a member of the High collegium in 2026. Justice Nagarathna is also due to become the first female Chief Justice of the Indian Supreme Court in 2027. However, she will hold the office for less than 5 weeks.

The extent of marginalisation of female members is evident from the fact that the latest instance of a female member's involvement in the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court is 2006. Cumulatively, female members have been involved in only 11 per cent of the judges appointed by the Supreme collegium (16 out of 144). These numbers are heavily influenced by Justice Pal who alone was involved in the appointment of nine judges. Two female members (Justices Ranjana Prakash Desai and R Banumathi) have not been involved in a single appointment. None of the female members have been involved in the appointment of another female judge.

Caste

There are three caste groups which are recognised for the purposes of affirmative action policies in India; (1) Scheduled Castes, (2) Scheduled Tribes and (3) Other Backward Classes. Scheduled Castes are caste communities notified under Article 341 of the Indian Constitution which suffered from the practice of untouchability. Scheduled Tribes are notified under Article 342 of the Indian Constitution which seeks to provide constitutional protection to the interests of the vulnerable tribal population in the country. Other Backward Classes refers to the collectivity of backward castes other than Scheduled Castes identified under the constitution for affirmative action policies under different nomenclature such as ‘socially and educationally backward’Footnote 62 and ‘backward classes of citizens’.Footnote 63 All communities other than the three categorised above are normally referred as General category.

The lack of any scheme of affirmative action in the higher judiciary is unlike the subordinate judiciary in India where reservation of posts on the basic of caste is well established.Footnote 64 With this backdrop, the study of caste representation in the collegium leads to deeply interesting findings and significant outliers. As there has not been a judge in the Supreme Court from amongst members of the Scheduled Tribes, the analysis here focuses on Scheduled Caste and Other Backward Classes.

Scheduled Caste Judges in the Collegium

Since 1993, there have only been three Scheduled Caste judges appointed to the Supreme Court; Justice KG Balakrishnan in 2000, Justice BR Gavai in 2019 and Justice CT Ravikumar in 2021. This constitutes 2 per cent of all judges appointed since 1993. Justices Balakrishnan and Ravikumar belong to the southern province of Kerala, whereas Justice Gavai belongs to Maharashtra.

Justices Balakrishnan was the Chief Justice of India for a period of 1214 days. Justice Gavai is scheduled to be the Chief Justice for a period of six months after the retirement of Justice Sanjiv Khanna in May 2025. As Justice Gavai is scheduled to become a member of the Supreme collegium in June 2023 and a member of the High collegium in December 2023, his membership has not been included for the analysis in this section. Justice Ravikumar is not due to become a member of the Supreme collegium.

Justice Balakrishnan is an extreme outlier in almost every way apart from the fact that he is male. He is from the Scheduled Caste and comes from the regional province of Kerala which has contributed only two other members to the Supreme collegium and only one other member to the High collegium. The other two members in the Supreme collegium (Justice KT Thomas and Justice Kurian Joseph) have been involved in a total of 14 appointments, which is less than 50 per cent of the appointments that Justice Balakrishnan has been involved in. While he is not a judge from HC-Service,Footnote 66 he did serve in the subordinate judiciary before resigning and starting his legal practice.

The membership of Justice Balakrishnan constitutes just over 1 per cent of all Supreme collegium members and 2 per cent of all High collegium members. His share in the combined collegium-tenure is 4 per cent in case of the Supreme collegium and 5 per cent in case of the High collegium. No other member of either collegiums has had a higher share. Justice Balakrishan was a member of the Supreme collegium for 49 per cent of his time as a judge in the Supreme Court. Only two judges have spent a higher share of their judicial tenure as a member of the Supreme collegium. However, none of those two judges spent even close to the 1791 days that Justice Balakrishnan spent as a Supreme collegium member.Footnote 67 Justice Balakrishnan's membership of the High collegium comprised 45 per cent of his tenure as a Supreme Court judge which is the highest amongst all High collegium members. Also, no other member had a longer tenure in the High collegium than that of Justice Balakrishnan (1646 days).

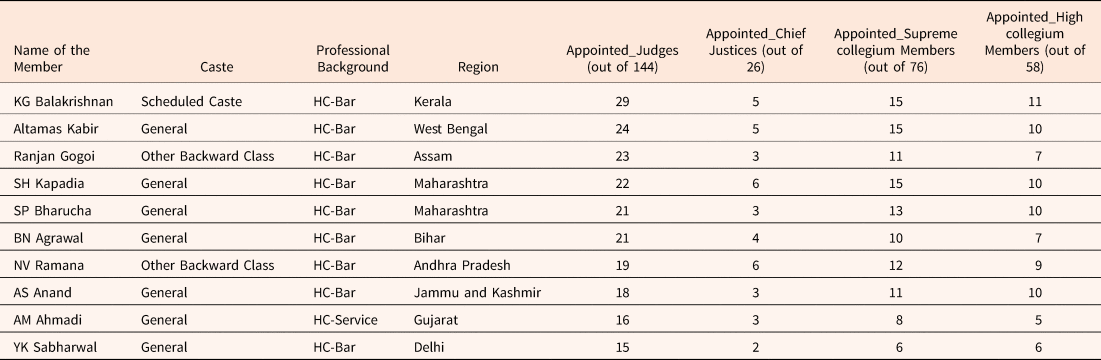

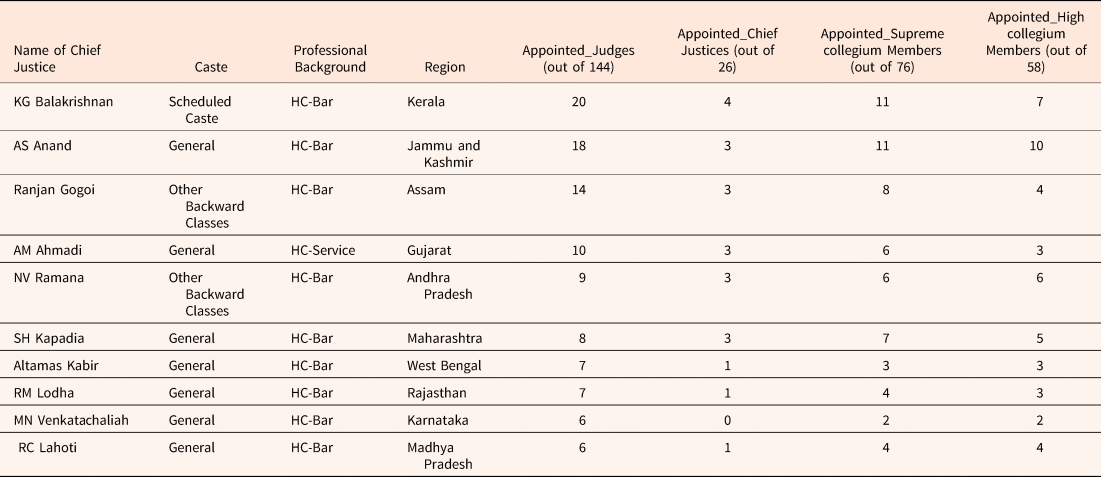

In terms of appointments, Justice Balakrishnan has been the most influential member of the Supreme collegium and also the most influential Chief Justice. As a member of the Supreme collegium, he has the highest share amongst all members in the appointment of Supreme Court judges, Supreme collegium members and High collegium members (Table 6).Footnote 68 He was involved in the appointment of 19 per cent of all Chief Justices appointed under the collegium system,Footnote 69 which is next only to the share of appointment of Justice SH Kapadia from the province of Maharashtra (23 per cent). It is important to highlight that Justice Balakrishnan was not involved in the appointment of any judge from the Scheduled Castes and only one judge from Other Backward Classes (Justice BS Chauhan).

Table 6. Ten Most Influential Supreme collegium MembersFootnote 70

Justice Balakrishnan has been the most influential Chief Justice under the collegium system with Justice AS Anand from Jammu and Kashmir a close second (Table 7). As a Chief Justice, his share of appointments in relation to Supreme Court judges (14 per cent), future Chief Justices (15 per cent) and future Supreme collegium members (14 per cent) is the highest amongst all Chief Justices since 1993. In relation to the appointment of future High collegium members, his share (12 per cent) is second to that of Justice AS Anand (17 per cent).Footnote 72

Table 7. Ten Most Influential Chief JusticesFootnote 71

Importantly, Justice Balakrishnan's involvement in appointments as a Chief Justice constitutes a significant proportion of all the appointments he has been involved in. The general trend is that a judge's involvement in appointment as a Chief Justice constitutes smaller proportion of the overall appointments the judge has been involved as a member of the collegium. In this respect, Justice Balakrishnan is a clear outlier. The peculiarity of Justice Balakrishnan's case is stark when we take the example of Justice Altamas Kabir. Overall, both have been involved in the appointment of 15 future members of the Supreme collegium. As a Chief Justice, Justice Kabir was involved in only 3 appointments of this nature whereas Justice Balakrishnan was involved in 11 appointments. Similarly, overall, both of them were involved in the appointment of 5 future Chief Justices but the Justice Kabir's involvement as a Chief Justice was in relation to the appointment of only one future Chief Justice. As a Chief Justice, Justice Balakrishnan was involved in the appointment of 4 future Chief Justices.

The only case similar to that of Justice Balakrishnan in terms of numbers is that of Justice AS Anand where all the appointments he was involved in were as a Chief Justice. However, his was a special situation. Justice Anand became a member of the Supreme collegium when Justice MM Punchhi was the Chief Justice. During Justice Punchhi's tenure as a Chief Justice, there was a prolonged stand-off between the government and the collegium concerning the procedure which the collegium was supposed to follow while recommending names. This stand-off led to the Presidential Reference of 1998Footnote 73 wherein the court provided clarifications on the collegium's functioning. As a result of these circumstances, Justice Punchhi retired without appointing any judge and Justice Anand's first involvement in any appointment was when the succeeded Justice Punchhi as the Chief Justice.

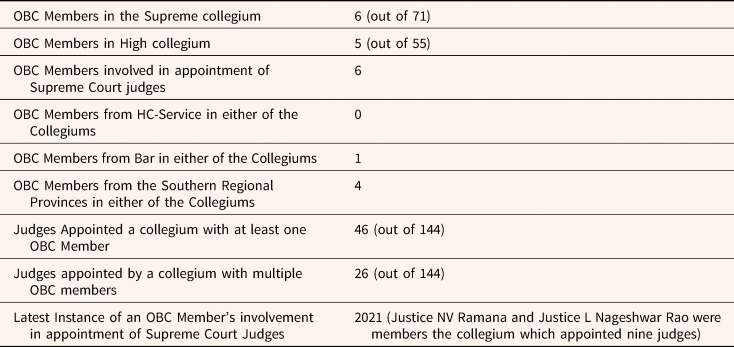

Judges from Other Backward Classes in the Collegium

Since 1993, there have been seven OBC judges in the Supreme Court (Justice S Ratnavel Pandian Justice BS Chauhan, Justice Jasti Chelameswar, Justice Ranjan Gogoi, Justice NV Ramana, Justice L Nageshwar Rao and Justice MM Sundaresh).Footnote 74 That constitutes 4 per cent of all judges who have held office during that period. Five of them have been members of both the Supreme collegium and the High collegium (Justice Nageshwar Rao has been a member of only the Supreme collegium) Two of them (Justice Gogoi and Justice Ramana) have been Chief Justices. Justice Sundaresh is due to become a member of the Supreme collegium in November 2025 and a member of the High collegium in February 2027. Out of the seven OBC judges, five are from southern provinces. Three (Justice Chelameswar, Justice Ramana and Justice Rao) are from Andhra Pradesh and two (Justice Pandian and Justice Sundaresh) from Tamil Nadu. When we include Justice Balakrishnan and Justice Ravikumar (both from Kerala) who are members of the Scheduled Caste, seven out of the nine judges from the marginalised caste communities belong to the southern provinces.

Table 8. Overview of the Members from Other Backward Classes in Supreme collegium and High collegiumFootnote 75

In stark contrast to female members, the share of OBC members in the combined collegium-tenure is the same as their share in the membership of the Supreme collegium (8 per cent). The average share of OBC members in the combined collegium-tenure in Supreme collegium is the same as that of members from the general category (just over 1 per cent). The same holds true also in terms of their average share in the combined collegium-tenure in High collegium (around 2 per cent).

Table 9. Influence of OBC Members in the CollegiumFootnote 76

With a steep rise in their influence over the last half a decade, OBC members have been involved in the appointment of forty-six judges which constitutes 32 per cent of judges appointed since 1993. Till 2016, OBC members were involved in the appointment of only ten judges. In this context, it is important to recognise the extent to which Justice Gogoi and Justice Ramana impact the numbers here. The two of them have been involved in 22 per cent of all appointment made by the collegium which also constitutes 70 per cent of appointments that all OBC members have been associated with. They have also been involved in 10 appointments where both of them were members of the Supreme collegium at the same time.

Individually, Justice Gogoi has been the most influential OBC member in the Supreme collegium. He is only the second judge from Assam to become a member of the Supreme collegium (the first was Justice HK Sema. Justice Hrishikesh Roy is scheduled to become the third member from Assam in 2024) Amongst all Supreme collegium members, Justice Gogoi is third in the list of members with involvement in maximum number of appointments (Table 6). Justice Gogoi has been involved in the appointment of 16 per cent of all collegium appointees. The trend is similar when it comes to appointing future Chief Justices and future members of Supreme collegium and High collegium. Overall, Justice Gogoi has been involved in the appointment of three future Chief Justices, eleven future Supreme collegium members and seven future High collegium members. All three future Chief Justices were appointed when Justice Gogoi was himself the Chief Justice. The corresponding number in relation to future Supreme collegium members and future High collegium members is eight and four.

The appointment of twenty-six judges have been recommended by Supreme collegiums which had more than one member from the OBC category. Justice Gogoi was involved in seven appointments along with Justice Chelameswar and ten appointments with Justice Ramana. Justice Ramana and Justice Rao have together been involved in the appointment of nine judges.

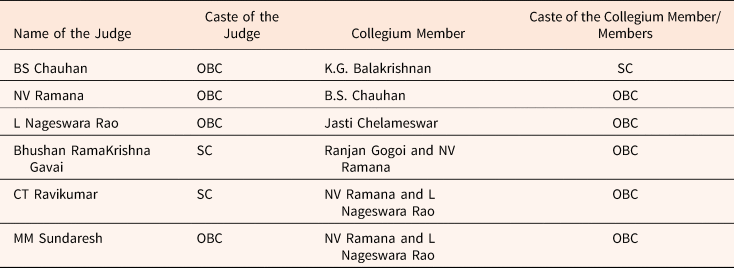

Other than Justice Balakrishan, Justice Chelameswar and Justice Gogoi, other members from the marginalised caste communities (Scheduled Castes and Other Backward Classes) have been appointed by a Supreme collegium which included a member from either from the Scheduled Caste or Other Backward Classes (Table 10).

Table 10. Involvement of Members from Marginalised Castes in Each Other's AppointmentFootnote 77

Brief Summary of Diversity of Caste in the Collegium

While Justice KG Balakrishan remains the only Scheduled Caste member in the Supreme collegium and High collegium till 30 September 2021, his is a truly unique case. Individually, he is the most influential Supreme collegium member and also the most influential Chief Justice over the last three decades. Apart from the appointment of Chief Justices where he comes second to Justice SH Kapadia, Justice Balakrishnan's involvement in the appointment of Supreme Court Judges (29 out of 144), Supreme collegium members (15 out of 76) and High collegium members (11 out of 58) is the most by any member of the Supreme collegium.

There has been a marked increase in the influence of members from Other Backward Classes since 2016. Till then, OBC members were involved in the appointment of only 10 judges. Between 2016 and 2021, OBC members have been involved in the appointment of 36 judges. 26 of those appointments have been made by collegiums with multiple OBC members. This rise in influence has been driven primarily by Justices Ranjan Gogoi and NV Ramana.

Out of the nine judges from the marginalised castes (Scheduled Caste or OBC) appointed by the Supreme collegium, six have been appointed by a collegium which had a member from a marginalised caste. Most of the members from marginalised castes belong to the southern provinces. Between 1993 and 2021, four out of the six OBC members of the Supreme collegium belong to the Southern provinces. With Justice MM Sundaresh (from Tamil Nadu) due to become a member in 2025, that number will stand at five out of seven.

Professional Background

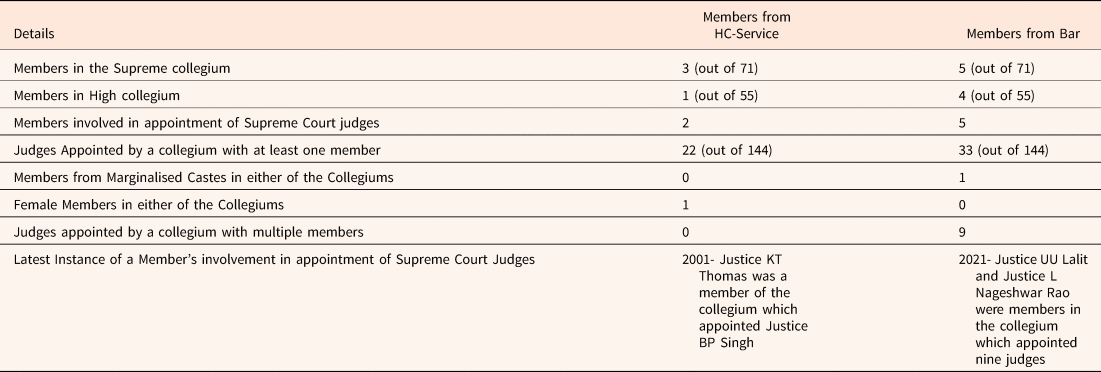

The Supreme collegium has engineered an era of extreme professional homogeneity in the Supreme Court. While theoretically individuals from three professional backgrounds are eligible to become judges in the Supreme Court,Footnote 78 the court has always been dominated by the pool of High Court judges who constitute 96 per cent of the Supreme Court appointees. In the Supreme Court, High Court judges appointed directly from the Bar (HC-Bar) have held a greater sway (86 per cent) than High Court judges appointed from the subordinate judiciary (HC-Service) who constitute 11 per cent of all appointees. However, this masks the squeezing out of judges with experience in subordinate judiciary over the last three decades under the stewardship of the Supreme collegium. Judges from HC-Service constitute only 5 per cent of the collegium's appointees and also have significantly shorter tenure than judges from other professional backgrounds.Footnote 80

Table 11. Overview of the Members from professional backgrounds of HC-Service and Bar in Supreme collegium and High collegiumFootnote 79

This professional homogeneity in the Supreme Court is quite clearly reflected in the Supreme collegium as well. Judges from HC-Bar constitute 89 per cent of all Supreme collegium members and their share in the combined collegium-tenue of all members is 88 per cent. The corresponding numbers for members from HC-Service is 4 per cent. Judges appointed directly from the Bar constitute 7 per cent of all members and their share in in the combined collegium-tenure is 8 per cent.

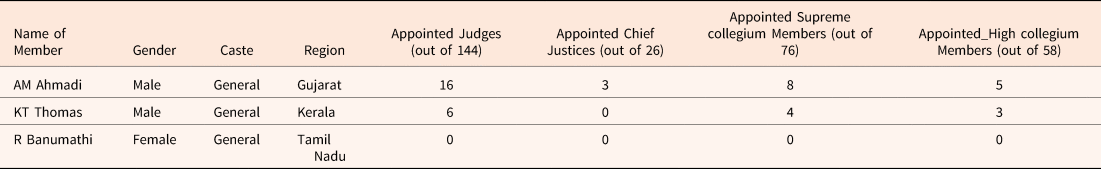

In the context of members from HC-Service, as low as these numbers are, they still hide the extent of marginalisation. Since 1993, there have been eight judges in the Supreme Court from HC-Service. However, there have been only three Supreme collegium members from HC-Service (Justice AM Ahmadi, Justice KT Thomas and Justice R Banumathi). One of them (Justice AM Ahmadi) was appointed by the executive. The other judges from HC-Service (Justice BL Hansaria and Justice SN Phukan from Assam, Justice C Nagappan from Tamil Nadu, Justice PC Pant from Uttarakhand) never became members of the Supreme collegium. Justice Bela Trivedi from Gujarat, who was appointed on 31 August 2021 is not due to become a member of the Supreme collegium in future.

If we discount the presence of Justice Ahmadi, the share of members from the cadre of HC-Service in the combined collegium-tenure of all members falls from 4 per cent to 2 per cent. Apart from him, there has been no other member from HC-Service in the High collegium.

The overall influence of members from HC-Service is similarly skewed due to the involvement of Justice AM Ahmadi (Table 12). He has been involved in a total of 16 appointments, out of which 10 have been as the Chief Justice. Justice Thomas has been involved in a total of 6 appointments. Justices Ahmadi and Thomas have been involved in the appointment of a total of three future Chief Justices, twelve future Supreme collegium members and eight future High collegium members. Justice Ahmadi was involved in the appointment of two judges from HC-Service (Justice BL Hansaria and Justice KT Thomas). Justice KT Thomas was not involved in the appointment of any judge from HC-Service.

Table 12. Influence of Supreme collegium Members from HC-Service BackgroundFootnote 82

The fact that Justice Banumathi has not been involved in a single appointment means that no member from HC-Service has been involved in an appointment since 2001.

The distribution of influence amongst collegium members from the Bar is more even (Table 13). There have been five members from the Bar (Justice Kuldip Singh from Punjab, Justice N Santosh Hegde from Karnataka, Justice RF Nariman from Maharashtra, Justice UU Lalit from Maharashtra and Justice L Nageshwar Rao from Andhra Pradesh). Justice Hegde has been involved in the least number of appointments (6) and Justice Singh has been involved in the greatest number of appointments (10). Since the inception of the collegium, there had not been a Chief Justice from the Bar cadre. Justice Lalit became only the second Chief Justice from the cadre of Bar after the retirement of Justice Ramana.Footnote 81

Table 13. Influence of Supreme collegium Members from ‘Bar’ BackgroundFootnote 83

Till 2021, there was never an instance of multiple members from the Bar being involved in the appointment of any judge in the same collegium. While the membership of Justice Lalit and Justice Nariman overlapped for over a year from 2020 to 2021, there were no appointments to the Supreme court during that time. However, the collegium including Justice Lalit and Justice Rao appointed nine judges in August 2021. Cumulatively, the collegium members from the Bar have been involved in the appointment of eight future Chief Justices, nineteen future Supreme collegium members and thirteen future High collegium members. No member from Bar has been involved in the appointment of another judge from Bar.

Table 14. Overview of Regional Representation in the Supreme collegiumFootnote 84

Out of the five members in the Supreme collegium, the membership of High collegium has been elusive only for Justice Rao. Together, members from the Bar constitute 7 per cent of the High collegium membership and have a share of 7 per cent in the combined collegium-tenure of all members in the High collegium.

Brief Summary of Professional Diversity in the Collegium

Much like the Supreme Court, there is stark imbalance in the compositions of the Supreme collegium and High collegium over the years in terms of professional background of the members. There have been only three members in the Supreme collegium from HC-Service and five from Bar (out of 71). In the High collegium, there has been one member from HC-Service and four from Bar (out of 55).

The dire representation of members from HC-Service is glossed to a substantial extent by Justice AM Ahmadi who has individually been involved in 16 out of the 22 appointments that members of HC-Service have been involved in cumulatively. The last instance of a member from HC-Service being involved in the appointment of a Supreme Court judge was in 2001. Influence amongst members of the Bar is more evenly distributed with no member involved in less than six appointments. Nine judges have been appointed by a collegium with multiple members from the Bar (in 2021).

Region

The Supreme Court of India is not simply a constitutional court but also an appellate court which hears appeals from all parts of India. The regional provinces were established on the basis of linguistic identities and the cultural diversity across regions is often substantial. In such a scenario, the issue of regional representation becomes important while assessing the distribution of power in the context of judicial appointments. As of 30 September 2021, there are 28 States and 8 Union Territories in the country. In the federal scheme, while States enjoy considerable autonomy, Union Territories are primarily under the control of the Union Government.Footnote 85

Members from Maharashtra constitute 14 per cent of the total Supreme collegium membership which is the highest amongst all regional provinces. They constitute the highest proportion of members from any of the regional provinces in the High collegium (13 per cent) as well. Members from Maharashtra also top the list in terms of share in the combined collegium-tenue in both Supreme collegium (17 per cent) and High collegium (14 per cent) (Table 15).

Table 15. Regional Representation in Supreme collegium and High collegiumFootnote 86

Table 16. Regional Distribution of Influence in Supreme collegiumFootnote 87

By almost every metric, Maharashtra and Delhi constitute the most influential regional provinces in the Supreme collegium. Members from Maharashtra and Delhi have been involved in the highest number of appointments (50 per cent and 40 per cent of all collegium appointees). Members from Maharashtra have been involved appointing 62 per cent of Chief Justices, 61 per cent of Supreme collegium members and 59 per cent of High collegium members which is the highest proportion amongst all regional provinces. Delhi has the next highest numbers in relation to Supreme collegium members (37 per cent) and High collegium members (40 per cent). In relation to Chief Justices, Delhi occupies the fourth spot along with Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal.

The instances of multiple judges from the same regional province being members of the collegium at the same time are quite frequent. 50 out of the 144 judges have been appointed by the Supreme collegium with more than one member from the same regional province. Here also, Maharashtra and Delhi lead the pack. Collegium members from Maharashtra have been in involved in most such appointments (24) with members from Delhi (13) and Andhra Pradesh (9) next in the list. The other regional provinces from which multiple collegium members have been involved in the same appointments are West Bengal (6), Rajasthan (6), Bihar (5), Gujarat (4) and Karnataka (3).

The case of Delhi is unique. Before the conversion of the State of Jammu and Kashmir into a Union Territory in 2019,Footnote 88 Delhi was the only Union Territory with a High Court of its own. However, it is not one of the provinces which have had judicial prominence since the colonial era like Maharashtra. Before the inception of the collegium, there had been only two judges in the Supreme Court from the province of Delhi. In contrast, there were 12 judges in the Supreme Court from Maharashtra before the inception of the collegium. While the collegium has appointed 14 judges from Maharashtra, the number of judges appointed from Delhi stands at 15. In the list of judges appointed by the Supreme collegium, there is no other regional province with a higher proportion. The rise of Delhi as a judicial power centre seems entirely driven by the collegium model.

The case of Tamil Nadu is also notable. Historically, it was one of the epicentres of judicial authority along with Maharashtra and West Bengal. In the history of the Supreme Court, judges from Tamil Nadu constitute the second largest cohort after Maharashtra. However, since the inception of the collegium, there has been a marked decline in its influence. This was already evident in the progressively declining representation in the Supreme Court in terms of the number of judges from Tamil Nadu.Footnote 89 We can also witness the same within the Supreme collegium. Members from Tamil Nadu have been involved in the least number of appointments (17) in comparison to members from other regional provinces. Out of the four members in the Supreme collegium, two have not been involved in any appointment (Justice R Banumathi and Justice Doraiswamy Raju). Of the other two, Justice S Ratnavel Pandian (appointed by the executive) was involved in the appointment of three judges and Justice P Sathasivam was involved in the appointment of 14 judges.

Until 2021, the appointment of Justice SN Phukan was the only instance when the collegium had multiple members from more than one regional province. It included two members from Maharashtra (Justice SP Bharuchha and Justice Sujata V Manohar) and two members from Gujarat (Justice SB Majumdar and Justice GT Nanavati). In a rather rare incident, the collegium which appointed as many as nine judges in August 2021, had three members from Maharashtra (Justice AM Khanwilkar, Justice UU Lalit and Justice DY Chandrachud) and two members from Andhra Pradesh (Justice NV Ramana and Justice L Nageshwar Rao). This was the first such occasion when the collegium included three members from the same regional province and when the total membership of the collegium was restricted to only two regional provinces.

Brief Summary of Regional Diversity in the Collegium

Both in the Supreme collegium and the High collegium, many regional provinces (20 out of 36) have never had any representation. It is because of the fact that there have not been any Supreme Court judges from some provinces (Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Goa etc.) However, there are also few regional provinces (Uttarakhand and Telengana) who are not represented in either of the collegiums despite there being Supreme Court judges from the province. Members from the province of Maharashtra and Delhi constitute the most represented and the most influential cohort in both the Supreme collegium and the High collegium. Till 30 September 2021, members from Maharashtra and Delhi have been involved in the appointment of 72 and 58 judges appointed by the Supreme collegium (out of 144). Members from Tamil Nadu are the least influential cohort with involvement in the appointment of only 17 judges. There are seven regional provinces (Maharashtra, Delhi, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Bihar, Gujarat and Karnataka) which have had multiple members in the Supreme collegium at the same time. Maharashtra is the only province which has had three members in the Supreme collegium at the same time.

Inconspicuous Members

There have been eight members in the Supreme collegium who have not been involved in a single appointment. Most of such members had a really short collegium-tenure which is a reasonable explanation for their lack of involvement. All such members are from the general caste category and it includes two female members (Justice RP Desai and Justice R Banumathi). There are two members each from Bihar (Justice BP Singh and Justice CK Prasad) and Tamil Nadu (Justice Banumathi and Justice Doraiswamy Raju). There is one member each from Andhra Pradesh (Justice K Ramswamy), Maharashtra (Justice RP Desai), Punjab (Justice SS Nijjar) and West Bengal (Justice GN Ray). Apart from Justice Banumathi who was from HC-Service, all other members belong to the HC-Bar category. No collegium member from the Bar has been involved in less than six appointments.

There have been three members who failed to make a single appointment during their term as Chief Justice. Justice S Rajendra Babu was Chief Justice for a mere 30 days and his presence in this list makes sense. While Justice Bobde's failure to appoint a judge seems to have been due to resistance from within the collegium,Footnote 90 Justice MM Punchhi failed to appoint due to a significant standoff with the executive.Footnote 91

Conclusion

The findings in this article show that both the Supreme collegium and High collegium are dominated by upper caste male judges who have spent majority of their professional career as lawyers. Members from HC-Service and female members have not been involved in any appointment since 2001 and 2006 respectively. The influence of members from OBC caste has seen a sharp rise since 2016. While membership in both the collegiums is relatively more balanced when it comes to regional representation, members from Maharashtra and Delhi have clearly enjoyed greater influence.

The presence of singular outliers in the form of Justice Ruma Pal, Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice AM Ahmadi has relatively mitigated the extreme marginalisation of female members, OBC members and members from HC-Service respectively. Without these individual outliers, the representative share of the respective groups plummets significantly.

There is a visible lack of intersectionality in the representative identity of members. None of the female members are from the Schedule Caste or from the Other Backward Classes and none of the members from marginalised caste communities come from the background of HC-Service. Most of the members from the Scheduled Caste and Other Backward Classes are from the southern provinces and all female members belong to the regions of Maharashtra, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu.

We see greater marginalisation in terms of gender than in terms of caste. While there is lack of diversity in relation to both groups, female members have exercised significantly less power than members from Scheduled Caste or Other Backward Classes after joining the Supreme collegium. This is true in terms of share in the collegium membership and also influence within the collegium. While members from marginalised castes have been generally involved in the appointment of other judges from marginalised castes, no female member has even been involved in the appointment of a female judge.

While this article does not profess to analyse the specific factors which have contributed to the lack of diversity in the collegium, the findings are strongly suggestive that it is not accidental. There is clear evidence that while recommending the appointment of a judge, collegium members are acutely aware of the leadership role they want such a judge to play in the future and the future leadership role of a judge seems to be a clear factor in deciding on the timing of the appointment.Footnote 92 Thus, it is not accidental that the average age of a female member of the Supreme collegium at the time of being appointed to the Supreme Court is 60 and that of a male member is 58. As we have seen, this means that female members spend less time in the collegium and have less opportunity of being involved in appointments by the time they reach the age of retirement. Also, the average age of all female judges appointed by the Supreme collegium is 61 while that of the male judges is 60. In a system where seniority is determinant of hierarchical influence, a visible delay in appointment puts female judges in a significantly disadvantageous position. On the other hand, the average age of an OBC judge at the time of appointment is 59. The greater marginalisation of female judges can be directly traced back to this difference in the age in which they are appointed as judges and the age at which they become members of the collegium.

Similarly, an unwritten but quite entrenched policy in relation to appointment of High Court judges seems to have marginalised the prospects of judges from the professional background of HC-Service. In the appointment of High Court judges, there has been an upper ceiling of 30–33 per cent for members serving in lower judiciary.Footnote 93 This means that at any point of time, judges of HC-Service will constitute a maximum of 33 per cent of all the High Court judges in any regional province. The proportion may be less but is unlikely to be more. With majority of the Supreme Court judges coming from the pool of High Court judges,Footnote 94 the enforcement of this upper ceiling severely reduces the pool of judges from HC-Service who can be considered for a judgeship in the Supreme Court.

Additionally, judges from HC-Service are appointed at a more advanced age and consequentially have a shorter tenure in comparison to judges from HC-Bar. This means that they struggle to reach adequate seniority to assume leadership positions within the High Court itself. For example, as on 2 January 2023, out of the 25 Chief Justices of various regional High Courts in the country, nobody is from HC-Service.Footnote 95 When we link this fact with the policy of the collegium to usually appoint judges to the Supreme Court only after they have become Chief Justices in any of the High Courts,Footnote 96 the barrier for judges from HC-Service to become members of the collegium becomes evident.

As a reason, even when judges from HC-Service make it to the Supreme Court, it is often closer to the age of retirement and they have considerably shorter tenures.Footnote 97 This explains the reason why even when judges from HC-Service are appointed to the Supreme Court (seven since 1993), their prospects of becoming a member of the Supreme collegium are remote (only two since 1993) and the possibility of becoming a member of the High collegium is virtually non-existent (none after Justice AM Ahmadi who was appointed by the executive).

Existing scholarship has not addressed the impact of a homogenous collegium primarily because of the opacity with which it has operated since its inception. While we can notice traces of this impact on the selection of judges of the Supreme Court, the impact is likely to be much greater at the level of the High Courts which constitute much larger proportion of the higher judiciary in India. Members of the collegium have been able to escape public scrutiny of their role in appointment of individual judges primarily because there has been no publicly available record of their involvement.

Perpetual homogeneity in the Supreme collegium and the High collegium is a massive barrier in the efforts towards having a more diverse higher judiciary. The arguments in favour of a diverse judiciary are quite well establishedFootnote 98 and the scope of this paper does not allow a detailed analysis of the same. It is already established that the Supreme collegium has ignored certain kinds of diversity and also that the prioritisation of diversity has been slow.Footnote 99 As we can see in our discussion on caste, the presence of members from marginalised caste in the Supreme collegium seems to have had a positive effect in sustaining the continuance of caste representation in the Supreme Court. Although that does not seem to have been the case in relation to female members, it may have to do with the possibility of stronger patriarchal barriers in a judicial system dominated by men. Homogeneity in the composition of the appointing authority can foster subliminal biases which hamper the selection prospects of candidates from different social and professional background. It can also cloud the inherent subjectivities of a selection process and normalise the idea of an illusory objectivity in the assessment of candidates. Thus, it is vital that the links between the lack of diversity within a specific collegium and the extent of diversity in the selection record of such collegium (both Supreme and High collegium) is subjected to deeper academic scrutiny

While factors such as age of appointment and upper ceiling may indicate the manner in which the marginalisation of different social and professional groups is effectuated, that in itself does not explain the reasons behind the marginalisation. The focus of the article is not on an investigation of such reasons. However, it can be safely contended that the collegium lacks diversity by design. At the time of its inception, the collegium quite predictably reflected the historical legacy of social and professional composition of the Supreme Court. That it has mostly remained the same over the last three decades is a persuasive proof of the entrenched privileges of certain social groups in the judiciary.