Introduction

This article extends and develops our previous analyses of Berio's music.Footnote 1 Berio himself was a fierce critic of what he called ‘analytical positivism’,Footnote 2 the attempt to fit each segment of a musical work within a comprehensive theory. In his ‘Aspetti di artegianato formale’Footnote 3 Berio acknowledged the importance of simple, short structures within larger forms in his work, and this is also explored in analyses by StoianovaFootnote 4 and Osmond-Smith.Footnote 5 Form for Berio was a way to set boundaries to his invention, the composer working out local strategies, step by step, as a mise-en-forme (a form which is set with and within the piece).

In early studies this idea was presented but not fully developed; most analysis focused on the study of the ‘polyphonic possibilities of melody’ that Berio mentioned in his interview with Rossana Dalmonte.Footnote 6 The usual concerns of these analyses are with the ways in which Berio would simulate polyphony in a monodic structure, trying to demonstrate what Berio associated with forms of listening ‘that might constantly suggest a latent or implied polyphony’.Footnote 7

But what defines polyphony? It is not only the overlapping of different melodic layers but also the existence of layers which occur in parallel, a layer being defined by a spatio-temporal continuity – that is, a set of data that apparently belong to the same listening system in such a way that any interruption in the continuity of this set generates the expectation of its return or its disappearance. In a continuous spatio-temporality there is, for instance, a certain degree of predictability about what will happen in the neighbourhood of a point, since continuity depends on the difference between one point and another always being small.

Thus, polyphony is defined as the interplay between two or more continuous fields whose relationship when overlapping is not functional (one determined by the other), but dialogical (each responding to the other). Berio drew on aspects of tradition, such as Bach's polyphonic writing in his partitas, sonatas and suites for solo instruments, and we will begin by highlighting the use of registers (high, medium, low) to distinguish melodic continuity within polyphony. These techniques were already present in Sequenza VII (1969), for example, and in Example 1 Silvio Ferraz's analysis shows how the layers within a single passage can be heard in two different ways.

Example 1: Luciano Berio, Sequenza VII (Ferraz, ‘Diferença e repetição’).

Both in Berio and Bach, polyphonic continuity is determined not only by register but also by the joint and gradual evolution of elements. In Example 2 Berio creates two proto-melodic lines within a simulated or latent polyphony; Example 3 shows a similar passage in Bach's third cello suite.

Example 2: Luciano Berio, Sequenza VII (Ferraz, ‘Diferença e repetição’).

Example 3: J. S. Bach, Suite No. 3 for solo cello, bars 21–24.

Berio, however, also explores a third approach to polyphony that does not characterise polyphonic layers through linear continuity but sharply differentiates them through vertiginous leaps between different elements and changes in instrumental activity, as Example 4 demonstrates.

Example 4: Luciano Berio, Sequenza VII, opening (Ferraz, ‘Diferença e repetição').

Here Berio constructs a polyphony around a single note, using changes in fingering to characterise different timbres for every attack: staccato and tenuto; different dynamics for each new attack: p > p – f – p – mf > p – mf > p – f – p. Each attack alludes to a field of continuity that is not, however, realised. This polyphony is not made up of a single continuity into which the layers are in dialogical response with one another; instead this is a polyphony of layers, latent with unrealised potential.

It is against these background elements that we present our analytical work on Sequenza XIV, begun in 1995 and completed in 2002 and the penultimate work in Berio's catalogue before his death. The piece was stimulated by Berio's satisfaction with Rohan de Saram's performance of his Il Ritorni degli snovidenia (1976–77), for cello and instrumental group, at the Venice Biennale. He decided to add a cello sequenza to his ongoing series of solo works and began a long process of composition that involved the exchange of cassette tapes and correspondence with de Saram.

Berio became fascinated with the traditional music of de Saram's native Sri Lanka, and when Berio met de Saram to work on the piece the cellist played him the ceremonial Kandyan drum, used in Sri Lanka to accompany the dances of Hindu rituals. From this material Berio derived both a 12-beat rhythmic sequence and, because the drum has skins on both sides, each played with two fingers to produce four different pitches, a way for the cellist to produce four distinct sounds by beating his right hand on the body of the instrument.

In an interview in January 2014,Footnote 8 Rohan de Saram reported how surprised he was to receive the first drafts of the piece, because he knew that Berio was suffering serious health problems. According to the sketches, the first version of the Sequenza was completed in April 2002 but did not have the entire first page with its rhythmic sections. These were added in a second version, completed in November 2002. The third version, released in February 2003, also contained many additional melodic sections and indications of bow position on the strings (ponticello and tasto). Berio and Saram intended to work again on many technical details in August 2003, but the composer died in May of that year.

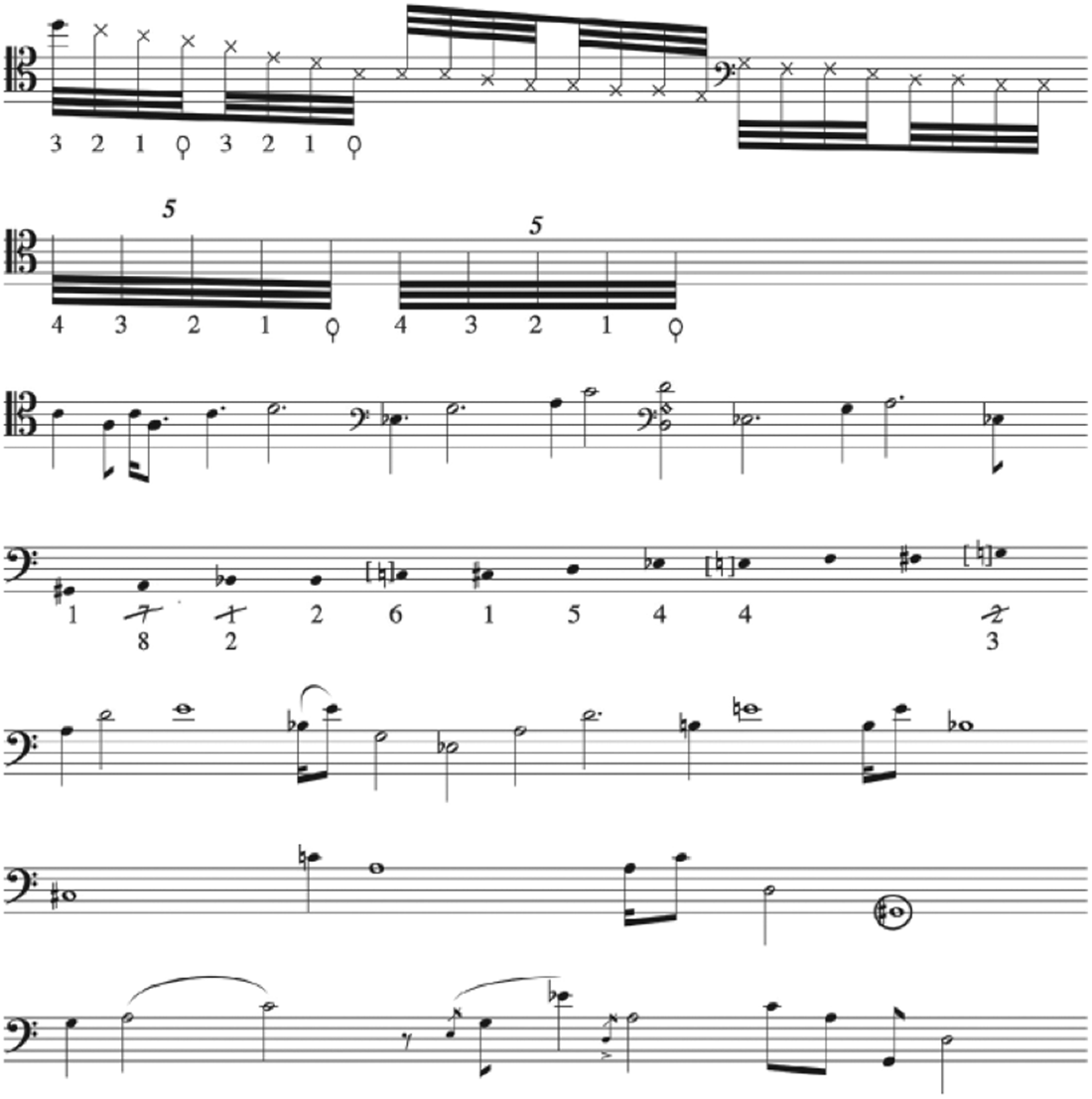

Analysing drafts of the score, now archived at the Paul Sacher Stiftung, reveals that Berio worked on the piece in short sections with no a priori form. Example 5 is a partial transcription of a sketch in which Berio conceives several figures that remained little changed until the end of the compositional process. The great cathedral-like ABA structure was only established in the third, final version.

Example 5: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, sketch (Berio Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung; partial transcription).

Each attack = an event

In Berio's music the equivalence between attacks, events and latent layers and their differentiated sound projection does not create a continuous time, as in Bach, but rather a continuous space, a place of sound projection. In this music polyphony is defined more by the delimitation of possible spaces (latent melody) than by defined continuities: polyphony is the simultaneous existence of these spaces. The composer does not depend on the listeners’ capacity to remember and relate sounds (he knows this is not plausible) but on their ability to notice these different spaces and that, each time a note is attacked again, the sound comes from another place.

This phenomenon was present in the opening of Sequenza VII (shown in Example 4), is heard early in the melodic part of Sequenza XIV and was also audible in another work for solo cello, Les mots sont allés… (1978), in which the last name of conductor Paul Sacher (to whom the piece is dedicated) serves as the motto for the distinction of the six notes and modes of attack with which the piece begins (see Example 6).

Example 6: Luciano Berio, Les mots sont allés…, lines 1–2 (© Universal Edition).

Here Berio achieves polyphony through an intense compression of musical elements, juxtaposing different modes of playing, in a way that might be heard as perhaps akin to the idea of stereometryFootnote 9 proposed by Ligeti in his analysis of Webern and in pieces such as the ninth of his Ten Pieces for Wind Quintet (1968).

Practical aspects

Any successful performance of Sequenza XIV must therefore carefully observe all those levels of relations between layers in order to highlight the work's polyphonic and stereometric aspects. Examples 7 and 8, for example, demonstrate how layers can be differentiated through the resonance of the different strings on which notes are played.

Example 7: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 2, line 1. Indication of strings by the authors (© Universal Edition).

Example 8: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 2, line 5. Indication of strings by the authors (© Universal Edition).

Berio developed this during his meetings with de Saram; the first version contained few indications of modes of playing but this subsequently became one of the most discussed topics in the compositional process. Table 1 shows some of the performance techniques they discussed. Many of these indications are omitted from the current edition of the score; the last meetings between the composer and de Saram resulted in further performance directions that have not yet been published but are discussed here as a result of our first-hand contact with the cellist.

Table 1: Initial draft of the modes of playing to be used in the piece (Berio Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, map 1)

Latent monody

An important feature of Sequenza XIV is Berio's use of reiterative models within the form of the piece, its polyphonic construction, and within individual passages. Shorter melodic passages often comprise a series of fragments, whereas longer passages are developed from the Sri Lankan rhythms that de Saram played to Berio. Berio also draws on elements from spoken language, as he had done in works such as Requies (1985) and Notturno (1996), and particularly on alliteration, a recurrent feature found in Les mots sont allés, Ricorrenze (1985) and Notturno. Of Notturno the composer notes that ‘several figures succeed each other maintaining a common detail; or a figure is repeated identical, even if distant, but with a different detail’.Footnote 10 This process also occurs in Sequenza XIV, in which a series of phrases share an appoggiatura-like figure as a central axis (see Figures 1a–1c).

Figures 1a–1c: Reiterations of a fragment around an axis figure in Sequenza XIV (© Universal Edition).

The principle of reiteration, permutation and timbral transformation is characteristic of the whole Sequenze series and was often mentioned by Berio in interviews. In Sequenza XIV it informs the transformation procedures that he applies to the Sri Lankan rhythms. Figure 2 shows de Saram's annotated transcription of the rhythms, indicating processes of addition and subtraction; Example 9 shows how these were finally realised in the score.

Figure 2: Drafts by Rohan de Saram (fax of 21 November 2001 to Luciano Berio) for Sequenza XIV (Berio Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, map 1).

Example 9: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 1 (© Universal Edition).

Towards a new polyphony

Researchers often focus on Berio's development of polyphony with monodic resources, but an important aspect of Sequenza XIV is its challenge to this pattern of polyphonic writing. Indeed, it proposes an entirely opposite approach, building a monody with polyphonic features, a technique that we might describe as an instrumental additive synthesis, in which one sound has the attack function and another serves as a resonance, something Berio had already suggested in pieces such as Requies and the Chemin series.

In Example 10 the score notates the left hand, initiating sounds by tapping the strings on the fingerboard, on the upper stave; the right hand, striking the top of the instrument's body to produce four different relative pitches, is notated on the lower stave. These are not distinct polyphonic lines, so the challenge for the performer is to homogenise the sounds within a single envelope, to create a synthesis where the attack comes from the right hand and the resonance is produced by the left hand. For the performer the main issue is the dynamic balance between the two sound sources: if the resonance of the attack on the body overwhelms the sound of the strings tapped by the left hand then the sense of synthesis will be lost. The articulation of pitches by the left hand is also clearly essential: it is not enough to hear only the knocking on the fingerboard.

Example 10: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 1. line 1 (© Universal Edition).

Example 11 shows further technical challenges for the performer in this first section of the piece. A high degree of coordination is required to play both lines simultaneously, as the two lines are neither exactly parallel nor perfectly contrary, and some cellists ignore the precise notation of the right-hand pitches, thereby failing to realise the synthetic entities prescribed by the composer.

Example 11: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 1, line 1 (© Universal Edition).

A publishing error in Example 11 does not help. The score's front matter prescribes that ‘where the music is notated on two staves the player is to produce a percussive sound that follows the contours and rhythms of the lower stave, played by four fingers of the right hand on the body of the instrument’,Footnote 11 but in the penultimate beat five pitches are notated. In discussion with de Saram we discovered that the first drafts for this section show five different sounds (see Example 12).

Example 12: Thematic development in Berio's compositional process after Saram's recording (Berio Collection, Paul Sacher Stiftung, microfilm 35, slide 502).

de Saram worked with Berio on a final edition for the music but the present one still contains many errors and omissions, and the front matter is a survivor from a period in the composition when Berio had intended to reduce all the percussive sections to four sounds.

The same section presents another performance challenge: amid the synthetic sequences are also the first polyphonic events, the pizzicato notes that anticipate subsequent developments and become a recurring figure in the piece. Examples 13 and 14 show its first appearances.

Example 13: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 1, line 1 (© Universal Edition).

Example 14: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 1, line 3 (© Universal Edition).

This gesture is very difficult to perform: the right hand pizzicati must stand out within the descending sequences and the more the different types of articulation are intermingled the more vital it is that there be clarity in their performance.

One more passage from the first page introduces a new element, a linearity of different types of sound emissions, creating a monody not through synthesis but through complementarity (Example 15).

Example 15: Luciano Berio, Sequenza XIV, p. 1, line 4 (© Universal Edition).

Here the performer must again pay strict attention to the right-hand pitches because they are part of the melodic contour that results from the combination of the two staves.

Conclusion

Sequenza XIV is a work in which a sort of stereometry or proto-polyphony is constructed out of hyperdifferentiated fragments. The Sri Lankan rhythms and the melodic structure represent separate musical identities that are reiterated and transformed through both simulated polyphony and a simulated instrumental synthesis. Performers must give especial consideration to the attack-resonance relationship between right and left hands, to the varied resonance of sounds played on different strings and to the differentiation of dynamics and timbre. We hope this article may contribute to the performance of this piece and to an understanding of Berio's instrumental writing.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Rohan de Saram for an interview about his collaboration on this piece, and to Angela DiBenedictis on behalf of the Paul Sacher Stiftung for access to the Berio Collection.