Joubert syndrome is an autosomal recessive congenital malformation of the brainstem and cerebellar vermis.Reference Joubert, Eisenring, Robb and Andermann1 Diagnosis is based on characteristic clinical features (e.g., hypotonia, episodic hyperpnea, developmental delay, progressive ataxia) and distinctive neuroradiologic findings (e.g., the “molar tooth” sign).Reference Joubert, Eisenring, Robb and Andermann1 Ocular manifestations of Joubert syndrome are retinal dystrophy, abnormal retinal pigmentation, ocular colobomas, oculomotor apraxia, nystagmus, strabismus, and ptosis.Reference Wang, Kowal and Ning2 Patients with Joubert syndrome commonly develop conjugate pendular nystagmus, gaze-evoked nystagmus, and seesaw nystagmus.Reference Wang, Kowal and Ning2 However, the occurrence of hemi-seesaw nystagmus has not been well documented in Joubert syndrome, and exact mechanism of hemi-seesaw nystagmus remains to be elucidated. We report oculographic characteristics of hemi-seesaw nystagmus and the results of vestibular functions tests in a patient with Joubert syndrome.

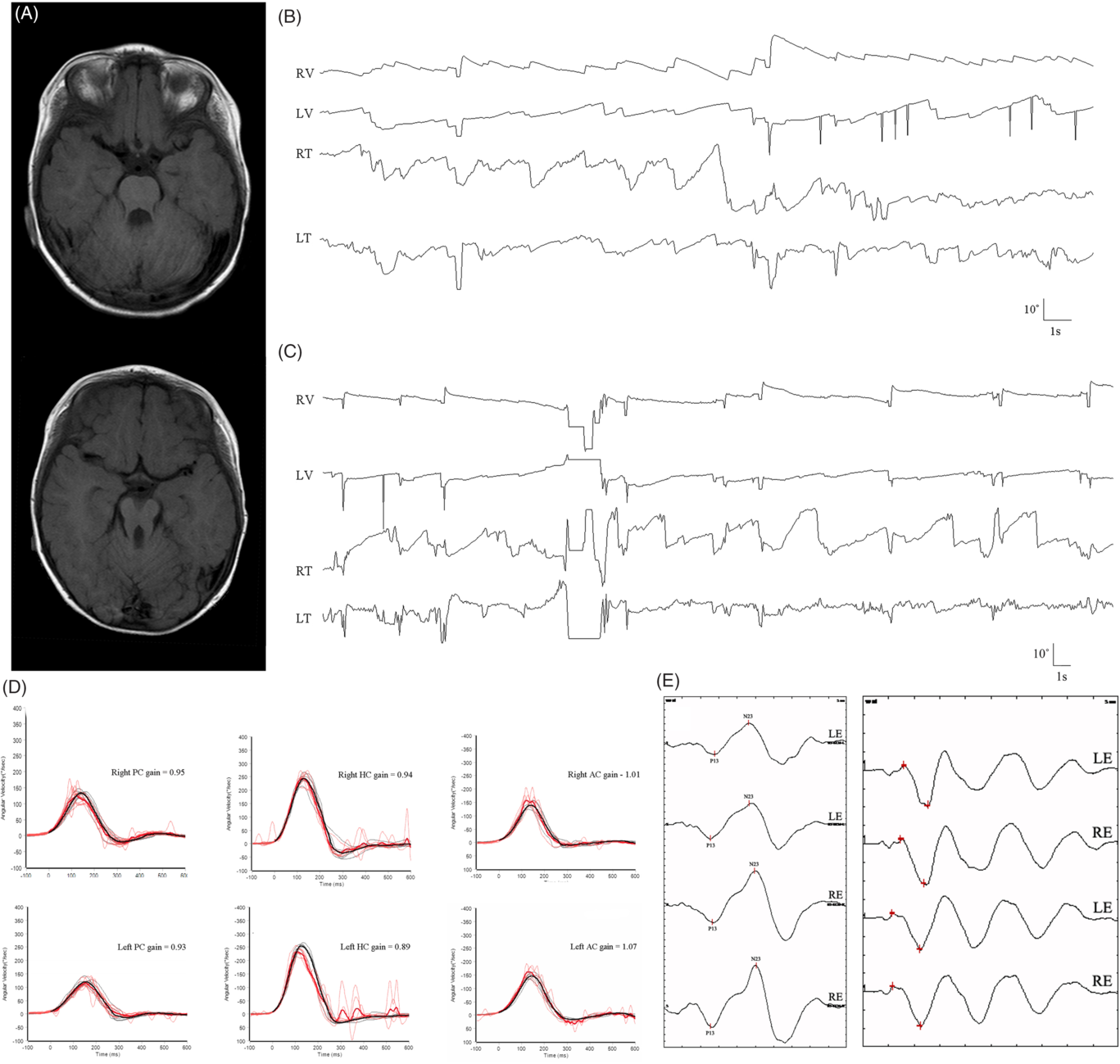

An 18-year-old man presented with oscillopsia, dysarthria, and imbalance since childhood. He was diagnosed with Joubert syndrome due to clinical signs of hypotonia, developmental delays, and midbrain-hindbrain malformation on MRI (“molar tooth sign”, Figure 1A) at the age of one. He had normal cognitive function. Video-oculography showed hemi-seesaw nystagmus comprising of extorsional downbeat nystagmus in the left eye synchronous with intorsional upbeat nystagmus in the right eye (counterclockwise from the patient’s perspective) (Figure 1B). The nystagmus beat at a frequency of 1–2 Hz. The amplitudes of intorsional upbeat nystagmus in the right eye (1.2°–21.0° and 1.0°–15.7°, respectively) were larger than the corresponding extorsional downbeat nystagmus of the left eye (1.1°–9.5° and 0.5°–5.3°, respectively). The vertical and torsional components of the slow phases mostly had linear waveforms. With visual fixation, the nystagmus was suppressed and the slow phases had exponentially decreasing or increasing waveforms (Figure 1C). The nystagmus was unaffected by changes in head positions, or in vergence angle. Horizontal head oscillation, vibratory stimulation, and hyperventilation also did not affect the pattern of nystagmus. Horizontal saccades were hypometric and smooth pursuit was impaired, bilaterally. There was no head tilt or skew deviation measured by a goniometer and cover-uncover test. Fundus photography did not show ocular torsion in both eyes, and subjective visual vertical tilt tests were also normal. Video head impulse tests (Figure 1D), and cervical and ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (Figure 1E) were normal. The patient had mild dysarthria and bilateral limb ataxia.

Figure 1: (A) Brain magnetic resonance images demonstrate absence of the cerebellar vermis and the “molar tooth sign” – an abnormal configuration of the superior cerebellar peduncles that connect the cerebellum to the midbrain. (B) Three-dimensional video-oculography shows hemi-seesaw nystagmus without visual fixation (extorsional downbeat nystagmus in the left eye synchronous with intorsional upbeat nystagmus in the right eye). The slow phases of vertical and torsional components have linear waveforms. (C) The nystagmus is suppressed by visual fixation, and the slow phases have exponentially decreasing or increasing waveforms. Video head impulse tests (D), and cervical and ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials (E) are normal.

Seesaw nystagmus is a conjugate torsional nystagmus with dissociated vertical components.Reference Leigh and Zee3 The waveform may be pendular or jerk, in which case the slow phase corresponds to one half-cycle and the quick phase to the other (hemi-seesaw nysagmus).Reference Leigh and Zee3 Pendular seesaw nystagmus is frequently associated with large parasellar tumors, chiasmal disorders, and visual loss, and it may arise when visual inputs necessary for stabilizing gaze in the frontal plane (rotation of the eyes around the naso-occipital axis) are compromised.Reference Leigh and Zee3 In contrast, jerk or hemi-seesaw nystagmus has been mostly reported with unilateral lesions in the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC),Reference Halmagyi, Aw, Dehaene, Curthoys and Todd4 medial longitudinal fasciculus,Reference Jeong, Kim, Lee, Choi and Kim5 and lower brainstem including the medial medulla.Reference Lee, Park, Jeong, Kim and Kim6 Hemi-seesaw nystagmus may be related to the ocular-tilt reaction (OTR) due to unilateral interruption of otolithic inputs from one labyrinth to contralateral INC, or an imbalance in the vestibular pathways probably a mixture of vertical semicircular canals and otolith signals.

In our patient with Joubert syndrome and hemi-seesaw nystagmus, the vertical semicircular canals, and static and dynamic otolithic functions were intact. These findings contradict the hypothesis that hemi-seesaw nystagmus is related to the OTR or reflects an imbalance in the vestibular pathways (probably a mixture of semicircular canal and otolithic signals) that mediates the dynamic response to head roll.Reference Migliaccio, Della Santina, Carey, Minor and Zee7 Given exponentially decreasing or increasing waveforms of the slow phases, hemi-seesaw nystagmus in Joubert syndrome may be ascribed to unilateral or asymmetrical impairment of the INC (the torsional eye-velocity integrator) with sparing of adjacent rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (torsional fast-phase generator). In support of this theory, experimental muscimol injection caudal to the INC produced hemi-seesaw nystagmus.Reference Das, Leigh, Swann and Thurtell8

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2019.343

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of Authorship

S.H.J. designed the study, interpreted and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. S.Y.C. and H.S.J. interpreted and analyzed the data. H.Y.C., E.H.O., and J.H.C. designed the study and drafted the manuscript. K.D.C. designed the study, interpreted the data, and made critical revisions of the manuscript.