Background

During the second millennium BC, there was a period of art internationalisation in the ancient world. By the Late Bronze Age (1650–1350 BC), prestige artefacts and styles had spread across western Eurasia, fuelled by the development of complex networks of political diplomacy, inter-regional exchange and mobility. In analysing the vast distribution of this period's elite art, Kantor (Reference Kantor1947) proposed that there was an artistic koiné—a style recognisable to and shared by elites throughout the region via the hybridisation of Aegean, Egyptian and Near Eastern visual elements, with a centre of production on the Levantine coast.

Following Kantor's argument, exotica and prestige/elite items have received considerable scholarly attention (e.g. Feldman Reference Feldman2006). However, the distribution and use of artefacts made from non-prestige materials are less researched. PLOMAT provides the first multi-layered analysis of ‘commonplace’ cylinder seals, including the so-called Common-style Mittani, which sheds light on non-elite networks of technologies, materials and images in Late Bronze Age western Eurasia.

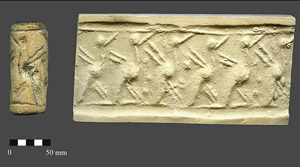

These types of seals (see example in Figure 1) are thought to belong to the cultural horizon of the Upper Mesopotamian Mittani hegemony (von Dassow Reference von Dassow, Radner, Moeller and Potts2022). The Mittani state, which emerged in the Jezirah region (i.e. its ‘core’), was a significant power in the Late Bronze Age; its influence extended as far east as Arraphe (modern Kirkuk), north to Lake Van, south to Terqa and west to areas such as Kizzuwatna, which was its ‘periphery’ (Cancik-Kirschbaum et al. Reference Cancik-Kirschbaum, Brisch and Eidem2014) (Figure 2). Here, this assumption is evaluated through a distribution analysis of Common-style Mittani and commonplace seals, while a contextual analysis hints at other possible factors determining such distribution patterns.

Figure 1. A commonplace seal from Minet el-Beida, AO 14818 (©2012 Musée du Louvre/Antiquités orientales).

Figure 2. Distribution of commonplace seals, with an indication of the Mittani ‘core’ and ‘periphery’ areas, after Novak (Reference Novak, Wittke, Olshausen and Szydlak2007). Regional subdivision follows ARCANE's classification (https://www.arcane.uni-tuebingen.de/arcanemap.html; accessed 14 December 2023) (figure by S.G. Russo).

Common-style Mittani versus commonplace

Common-style Mittani is an umbrella term introduced by Porada (Reference Porada1947) in her influential study of ‘Mittanian’ glyptic art from Nuzi, where more than 2000 unique seal designs impressed on clay tablets were identified. The term was deployed partly to distinguish such seals from contemporaneous examples in ‘Elaborate-style’ made of stone, with apparent differences in iconography and material, which often placed the former in a position of aesthetic inferiority in modern scholarship.

While Porada's work established Nuzi as the type-site for defining the Mittanian glyptic style, subsequent research has challenged this view (e.g. Stein Reference Stein and Caubet1997: 35; Yalçin Reference Yalçin2022: 185). The more recent studies note that dominant local features are more identifiable at Nuzi versus other Mittani-coded sites (Matthews Reference Matthews1990: 5), and they highlight the stylistic overlap between Common and Elaborate styles and the distinctiveness of seals used on documents versus those found in excavations. Further, the concentration of textual evidence (upon which seals were often impressed) in peripheral areas such as Alalakh and Nuzi, skews the understanding of a homogeneous ‘Mittani’ style (von Dassow Reference von Dassow, Radner, Moeller and Potts2022: 509), suggesting a more complex and varied glyptic landscape.

Therefore, expanding Porada's classification, beyond the limiting geographic conception of ‘Common Mittani’, we employ the term ‘commonplace’ to refer to low-quality seals from the sixteenth–fourteenth centuries BC, made of composite vitreous materials (frit/faience), cut on the drill and engraved. Because of their common denotation, scholars have excluded them from the koiné of the second millennium BC (e.g. Aruz Reference Aruz, Aruz, Graff and Rakic2013). However, the use of these seals spread throughout western Eurasia (Salje Reference Salje1990) (Figure 2), transgressing boundaries more broadly and effortlessly than elite art, whose journeys required gift-giving mechanisms, extended trade routes and diplomatic alliances.

The assemblage

Commonplace seals appertain to schematic, simple and repetitive decorative motifs (Porada Reference Porada1947: 12), and are usually uninscribed. Overall, they illustrate the artistic limitations imposed by cutting discs. Typical motifs are the guilloche (an intricate pattern of interlaced curves), the human figures’ rounded cap/rolled turban and the bouquet tree. The composition is often based on antithetical groups and procession scenes, while geometric patterns, rows of animals, fish, birds and people predominate. Borders frequently feature at the top, horizontal end or between the seal's distinct registers (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Illustrations of designs on typical Late Bronze Age commonplace seals (figure by C. Tsouparopoulou).

PLOMAT recorded 1359 commonplace seals (including 107 seal impressions and clay sealings), employing a relational FileMaker database, integrated with ArcGIS 10.8.2 (Esri Reference Esri2021) for spatial analysis. Data about each seal's context, material, motifs, design and chronology were compiled by scrutinising published excavation reports.

Regional and contextual distribution

Since Salje's Reference Salje1990 monograph, many commonplace seals have been excavated at sites from the Mittani core (e.g. Tell Munbaqa, Tell al-Hamidiya) and peripheral regions. Figure 4 shows an updated frequency distribution, highlighting that most commonplace seals were found beyond the Mittani influence area, notably in the Levant or Western Iran. The under-representation of so-called Common-style Mittani seals in the Mittani core—constituting only about five per cent of the total assemblage—challenges their classification within the Mittani cultural sphere; instead, it implies their participation in broader networks of cultural interaction and exchange.

Figure 4. Frequency distribution of Late Bronze Age commonplace seals by regions (figure by S.G. Russo).

Contextual analysis indicates a predominant presence of commonplace seals in temples (17.1%) and graves (15.2%) (Figure 5), primarily in the Levant and western Iranian sites respectively (Figure 6; Table 1).

Figure 5. Bar chart showing the frequency distribution of Late Bronze Age commonplace seals by contexts (figure by S.G. Russo).

Figure 6. Bar chart showing the relative frequency of Late Bronze Age commonplace seals by regions and contexts (figure by S.G. Russo).

Table 1. Table showing the counts of Late Bronze Age commonplace seals by regions and contexts.

Abbreviations for contexts: U: uncertain; G: grave; T: temple; Ub: undefined building; H: house; P: palace; S: surface; Pb: public building; R: room fill; Sr: storeroom; W: workshop; Os: open space; C: cave; Ru: rubbish dump; F: fortress; O: other; St: street; A: archive.

PLOMAT also established that seals are conspicuously absent from the elites’ monumental tombs (Drakaki Reference Drakaki2008; Iskra Reference Iskra, Pieńkowska, Szeląg and Zych2019). In southern Levant, the seals largely formed part of offerings in temples, accessible to varied social classes (e.g. Lower City temple at Hazor Area H; Zuckermann Reference Zuckerman and Kamlah2012).

The project's data analysis positions commonplace seals—once undervalued and examined mainly for their visual attributes—as key indicators of cultural and visual interconnectivity across the Mittani region and beyond. Their distribution and contextual usage reveal intricate networks facilitating motif transfer and physical flow across western Eurasia. Further research will apply x-ray fluorescence among seals from Greece to identify potential production clusters and employ computational image analysis to explore their stylistic and distribution patterns. These will enhance PLOMAT's insights into the complex dynamics of ‘everyday’ exchanges and communication in Late Bronze Age western Eurasia.

Acknowledgements

We thank Silvia Ferreri and Kyra Kaercher, who contributed to data collection, and Eric Cline and Diana Stein, who provided valuable feedback.

Funding statement

PLOMAT received funding from the EU Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreements (nos. 748293 & 951328) and Wolfson College, Cambridge, for the period 2018–2022.