This book emerged as a serendipitous part of my wider research on the church of Simon Kimbangu, a religious institution born in Central Africa (officially recognised in Belgian Congo in 1959) out of an anti-colonial prophetic movement started by the preacher Simon Kimbangu in the southern provinces of the Belgian Congo in 1921. From being a local prophetic movement in a tiny Kongo village, Kimbanguism has become a world church with several million followers in many countries. It has also become a paradigmatic case study for students of African religion who want to highlight the relationship between religion, contestation, oppression and spiritual independence.

I met Kimbanguists for the first time in February 2006 in Lisbon, and I immediately became a keen follower of their activities. There was a continuity but also a rupture in my research interests. In my previous work about African religion, I had been looking at the effects of an anti-colonial Muslim-inspired religious movement in Guinea (Sarró Reference Sarró2009). This triggered my interest in prophetic religious culture, prophetic imaginations and the relationship between religion and creativity, which I have studied ever since in Guinea-Bissau and in Kongo (Angolan and Congolese) prophetic movements. In 2006, while employed at the University of Lisbon, I became interested in prophetic diasporas in Portugal and embarked on a series of research projects on religious pluralism in the Portuguese capital and in the Lusophone world (Sarró and Blanes Reference Sarró and Blanes2009; Sarró and Mélice Reference Sarró, Mélice, Fancello and Mary2010). In 2006, thanks to Father Rui Pedro, a Catholic priest who was very active among migrant communities and with whom I organised several inter-religious dialogue and ecumenical activities in Lisbon between 2004 and 2010, I got to know of the small Kimbanguist parish of Apelação, a neighbourhood in the banlieue of Lisbon. I started to attend services after getting in touch with the community; very early on, I began to be invited into households. Less than a year later, I found myself doing fieldwork with them in northern Angola and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and I became totally immersed in a new project that, to a large extent, is still ongoing. I maintain very strong links with the Portuguese Kimbanguist church, I attend services when I am in Lisbon (where I live whenever I am not teaching in Oxford), and I continue studying Kikongo and other aspects of Kongo culture with my Kimbanguist friends, most of whom are originally from Angola. In 2009–11, I directed a research project on African churches in Europe that allowed me to become familiar with Kimbanguist parishes in other European countries, and in 2014–17 I was a member of a European project on religious heritage in the Atlantic for which I conducted fieldwork in Mbanza-Kongo (northern Angola), the ancient capital of the Kingdom of Kongo.

One of the things that captured my immediate attention on the first day when I visited the Kimbanguist parish in Apelação was a panel of pictures on the wall with several Congolese and Angolan news articles about a man called Wabeladio Payi and about an alphabet that Kimbanguists used, called Mandombe (literally meaning the alphabet, or the writing system, of Africans). The pastor explained to me that Wabeladio Payi, a Congolese man, had received that alphabet from God and had given it to the people. That was my first contact with the Mandombe alphabet. At the time, it caught my eye because just a few years earlier I had read Jean-Loup Amselle’s book on the Mandingo N’Ko alphabet (Amselle Reference Amselle2001), which made me realise how little we know of the social and individual processes that lead to the emergence of graphic systems in Africa. It struck me that, as with N’Ko, I was being confronted with a case in which the origin of an alphabet was connected to a religious revelation.

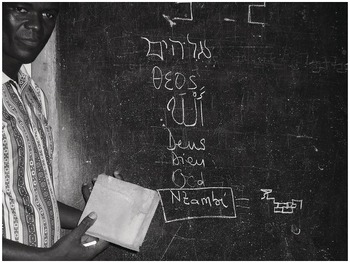

One year later I was to learn about Mandombe in Angola. In November 2007, in a long, detailed lecture at the headquarters of the Kimbanguist church in Luanda, Lei Gomes, a Brazzavillian teacher of Mandombe, told us that God had sent the Mandombe script to the Congolese Wabeladio Payi so that he could give it to Black Africans, providing them – like the Muslims, Hebrews and Western Christians – with their own script (Figure 1.1). In order for a society to be considered a ‘civilisation’ and not a mere ‘culture’, Lei explained, it needs a prophet, a God, a temple, a calendar and an alphabet. For many years, before Mandombe, Africans had had to rely on the Western alphabet and were forced to write God’s name (Nzambi in Kikongo) in Roman script, in what he called ‘linguistic colonialism’. In accordance with a prevailing model in Central Africa (Fabian Reference Fabian, Ntarangwi, Mills and Babiker2006), in which colonialism is portrayed as a technology designed to make people forget about previous aspects of local knowledge, their God or gods, languages, writing systems, names and crops, among other things, Lei told us that African writing systems had existed in the past. Thus, what Wabeladio was doing was an exercise in recovery, in historical and cultural remembering.

In October 2009, during my third visit to Africa with my Kimbanguist interlocutors from Lisbon, I went to the DRC. Among my Lisbon friends was José Emery Kimbamba, a man known in the Kimbanguist community for his witty spirit and sense of humour. The first night we were in Kinshasa, Kimbamba introduced me to someone at the Centre d’Accueil Kimbanguiste, the biggest urban headquarters of the church in the world.Footnote 1 Pilgrims were gathering there to begin a major pilgrimage to the holy city of N’kamba–New Jerusalem, some 200 kilometres to the south. Suddenly, in the midst of hundreds of people, Kimbamba said to me: ‘Ndoki, let me introduce you to Wabeladio Payi.’ Perhaps owing to my joking relationship with Kimbamba – who at the time I called my mfumu (chief) and who was the only person I would allow to call me ndoki (a ‘witch’) – I did not believe he meant the Wabeladio Payi I had heard so much about since beginning my research on Kimbanguism almost four years earlier. Therefore, I said: ‘Wabeladio Payi? Like the inventor of Mandombe?’ Wabeladio laughed and clarified: ‘I am the inventor of Mandombe!’ For some reason, I was expecting the inventor to be a much older man. Wabeladio was 52 years old and looked younger. The next day, Kimbamba and I went to the holy city of N’kamba in a car. Wabeladio followed us in a different car. We met again in N’kamba the next day and started talking immediately. Coincidentally, we were both to be received by the spiritual chief, Simon Kimbangu Kiangani (the grandson of the founder Simon Kimbangu), and therefore we had to sit together in the waiting room for hours.

It was then, in that waiting room at the end of 2009, that Wabeladio gave me a succinct account of his life and revelation. And it was then, too, that we decided to write together a book about him and about Mandombe, and we began brainstorming on how to tackle the collaborative project. Wabeladio wanted the book to consist of three parts: a biography of the inventor (himself); a biography of Simon Kimbangu (his inspiration); and the structure of the graphic system Mandombe in its dimensions of both writing and art. He had already authored some texts and had many manuscript notes that we used in our brainstorming. Sadly, Wabeladio passed away in 2013, still young and very painfully. I was very lucky that, by then, we had recorded his entire biography, in very long sessions that took place either in the DRC or in Europe, where he spent time in May 2010 and June 2012 (he had lived in Europe for more than six months some years before we met). For the second part of the book, where the linguistic and aesthetic dimensions of Mandombe are analysed, I had to rely on what he had explained to me, his unpublished manuscripts, and the help of his closest collaborators in Kinshasa, who included his widow Eugénie Dinkembi.

Wabeladio often came to our meetings, where I would take notes and record him speaking with texts he had written beforehand. In the beginning he used the third person singular, saying ‘Wabeladio’ did this or felt this, instead of ‘I’. Although we both realised it was often easier for him to speak of himself in a semi-fictionalised way, objectifying himself as the main character of an adventure, we decided early on not to do so, as it was very confusing for both of us, especially because the narrative often dealt with Wabeladio’s grandfather, who was also called Wabeladio – the pronoun ‘he’ often made it impossible for me to know whether he was speaking of himself or of his grandfather, with whom he identified in many ways. Besides, this way of presenting his life made the narrative stilted and made it uncomfortable for me to interrupt for clarification or to open up a more improvised dialogue; so, we started all over again. As the reader will find in the first chapters of this book, the biography (which is but a tiny summary of the very detailed account Wabeladio offered me) was recorded episode by episode, and every single episode was told at least three times, while sitting in his office at the University Simon Kimbangu in Kinshasa or at his home, while driving or using public transport in the lands of southern Congo (in the provinces of Kongo Central and in the city of Lubumbashi), while walking through the streets or driving on the roads of Portugal and Spain (which we visited together in 2010), or while sitting in my office at the Institute of Social Sciences of the University of Lisbon. Apart from talking to each other, we also interviewed together most of the people he mentioned as having been important in his life and who were still alive in Kinshasa, N’kamba or Lubumbashi. I continued with these interviews after his death, either with Eugénie Dinkembi or with Wabeladio’s closest collaborators.

* * *

Learning about Mandombe in Luanda through Lei Gomes in 2007 made me realise that, in some contexts, where a community is able to use its own alphabet – especially one God has sent to one of its members – that alphabet becomes much more than a communication tool: it becomes an end in itself. In fact, by the time Wabeladio passed away in 2013, there had been thousands of learners of Mandombe in the DRC, Angola, France and other countries, but there were relatively few regular users. It was the performance of learning that brought people together. Not everybody who learned Mandombe made much use of it, but they all felt a deep pride in having gone through the collective process of studying it. I should add here that I speak in the past tense not because Mandombe has now disappeared (all the teachers trained by Wabeladio are still active), but because the bulk of my research stopped with Wabeladio’s death on 4 April 2013. More than Mandombe itself, the topic of this study is the connection between Wabeladio’s biography and Mandombe.

Alphabets and the Struggle for Recognition

Today, Lei’s introductory lesson on Mandombe in Luanda resonates in my memory with a conversation I had in 2011 with Rubain Watulunda, a Kinshasa painter whose work I discuss in Chapter 7. Watulunda explained that there had been an ‘epistemological crisis’ in Africa. Owing to the hegemony of Western modes of thought, Watulunda argued, Africans had been forced to base their identity on Western science, Western writing, Western religions and Western aesthetics, and this had led to a deep identity crisis. Africans were not truly themselves; they had to use external things even to express their identity. Mandombe offered the possibility for Africans to start from zero with something that had emerged out of Africa and that could become art, writing or science.

Unlike many of his followers, Wabeladio Payi was not at all convinced that you needed anti-colonial theory or attitudes to explain his invention. For him, Mandombe was an invention, and that was all. ‘I have told them many times to stop presenting Mandombe in this way,’ he said to me when I summarised his Luandan disciple Lei’s words. On one occasion, he told me that he had developed Mandombe so that people could choose between alphabets. ‘It is not one or the other; nobody should abandon the Roman alphabet because they can write using Mandombe. It has to be regarded as having two pairs of trousers: you can choose which one you want to wear for this or that occasion.’ Wabeladio often criticised those who tried to bind Mandombe too tightly with ideology, and often expressed his misgivings about the usefulness of the concept of ‘linguistic colonialism’. Yet, the intimate connection between ‘civilisation’ and ‘writing’ made by many of his followers needs to be explored in order to have a better understanding of the conditions of possibility of the reception of Mandombe, different as they may be from the conditions of possibility of its invention. These two concepts, invention and reception, have been twins for a very long time. In what is now a classic volume on the history of writing, Ignace Jay Gelb stated that, according to authors such as Carlyle, Kant, Mirabeau and Renan, the invention of writing was ‘the real start of civilization’. And, he added, much to my embarrassment as an anthropologist: ‘These opinions are well supported by the statement so frequently quoted in anthropology: as language distinguishes man from animal, so writing distinguishes civilized man from barbarian’ (Gelb Reference Gelb1952: 221). For Gelb, echoing Rousseau, the equation was simple: if you had no writing you were a barbarian.

Much as we may think that there is sheer racism in such a straightforwardly divisive formula, the truth is that no one today would like to live in a world without writing. The number of things – starting with education and the ability to learn many other skills – from which one would be excluded is just too huge. Some authors, starting with Lévi-Strauss (Reference Lévi-Strauss1955), have minimised writing’s importance in the transformation that made it plausible to speak of a transition from ‘prehistory’ to ‘history’, or in the distinction between ‘unlettered’ and ‘lettered’ societies, as Clifford Geertz – also critical of the ‘easy contrast’ around a ‘literacy revolution’– ironically put it (Geertz Reference Geertz1976: 1481). Many others, however, such as Gelb, Samuel N. Kramer, in his classic From the Tablets of Sumer (Reference Kramer1956), and his interlocutor in France, Jean Bottéro, would subscribe to the grand notions of Carlyle and the like and consider that the invention of writing was essential in establishing an irreversible step between prehistory and history or even between ‘cultures’ and ‘civilisation’ (Bottéro Reference Bottéro and Kramer1957) – a problematic distinction that, as we see in Luanda today, is still being used by local actors to express their perception of their exclusions.

There are many aspects to the impact of writing in human history. In the 1960s, Jack Goody began a series of studies on the effects of literacy on cognition and on social, political, and religious organisation (Goody Reference Goody1968; Reference Goody1986). Many authors have followed his seminal input and have explored how writing technologies intermingled with local politics and with identity struggles in different parts of the world. But the inner workings of writing systems and the life and work of those rather unique, often prophetic individuals who invent them have not been explored so thoroughly. My main interlocutors in this study are therefore scholars working on the invention of prophetic alphabets, starting with the key works by Grant Foreman on Sequoyah, the inventor of the Cherokee alphabet (Foreman Reference Foreman1938), and, more importantly, the ground-breaking study by linguist J. Smalley and his collaborators on the Hmong prophet nicknamed the ‘Mother of Writing’ (Smalley et al. Reference Smalley, Vang and Yang1990). Recent studies, such as Amselle’s work on the West African N’Ko alphabet (Reference Amselle2001), Bordas’s work on the Ivorian script invented by the visionary artist Félix Brouade (Reference Bordas2010), Hales’s work on Nsibidi writing (Reference Hales2015) and Orosz’s work on the writing of the Bamoun chief Njoya (Reference Orosz2015), have made scholars aware of the importance of either developing new African scripts in the postcolony (as in the case that is the focus of this study) or at least knowing about previous ones. Meanwhile, the work of Pierre Déléage (Reference Déléage2013; Reference Déléage2017) has highlighted examples in American contexts that illustrate the prophetic conditions of possibility for the emergence of writing systems in non-Africanist contexts.

Africa has been the scene of the birth of very complex graphic systems that have undoubtedly been instrumental in transmitting cosmological notions and senses of cultural identity. Examples of this include the Dogon, studied by the Griaule school (Griaule and Dieterlen Reference Griaule and Dieterlen1951; Cissé Reference Cissé and Dieterlen1987; Zahan Reference Zahan1950), and, more relevant here, the Kongo graphic systems studied first by Robert Farris Thompson (Thompson and Cornet Reference Thompson and Cornet1981) and much more recently by his successor Bárbaro Martínez-Ruiz (Reference Martínez-Ruiz2013), who has demonstrated the need to move beyond Eurocentric ways of looking at writing systems if we are to grasp the ritual cosmological significance of the symbols the Bakongo and their diasporas have been using in their inscriptions for centuries. Since precolonial times, some graphic systems (though not precisely the Kongo ones studied by Martínez-Ruiz) have clearly been alphabetical; these have been the subject of a large bibliography by authors writing in colonial times (van Gennep Reference van Gennep1908; Delafosse Reference Delafosse1899; Labouret Reference Labouret1935; Baumann and Westermann Reference Baumann and Westermann1948; Joffre Reference Joffre1943; Lassort Reference Lassort1951; Adams Reference Adams1947) and by contemporary authors who have either reviewed the existing literature on colonial writing systems from postcolonial and contemporary frameworks (Dalby Reference Dalby and Malcolm1967; Reference Dalby1968; Reference Dalby1969; Reference Dalby1986; Tuchscherer and Hair Reference Turner1995; Tuchscherer Reference Tuchscherer1999; Reference Tuchscherer, Appiah and Gates2005; Reference Tuchscherer, Krearner, Roberts, Harne and Purpura2007; Hales Reference Hales2015; Akoha Reference Akoha and Hountondji1994; Cissé Reference Cissé2006; Kelly Reference Kelly, Ferrara and Valério2018a) or have studied emerging systems and their competition with the Roman alphabet, which was introduced in much of Africa through colonialism (Pasch Reference Pasch2008; Reference Pasch2011). Whether graphic or alphabetical,Footnote 2 African writing systems are interesting for scholars for a variety of reasons. First, they are often intertwined with non-alphabetic design and are thus a very good source for studying the relationship between art and alphabets in graphic systems (Battestini Reference Battestini2006) and for countering the excessive, clearly too Eurocentric importance that alphabets have received in the history of what is now referred to as ‘graphic pluralism’ (Debenport and Webster Reference Debenport and Webster2019). Several writing systems in Africa are so deeply imbued with spirituality that they do not represent any sound at all, but instead try to capture through lines and drawings the lived experience of being connected to the cosmos, forcing us to ask ourselves what is this thing that we call ‘writing’ anyway. Webb Keane has offered a very compelling argument for the study of the spiritual logics underpinning many ‘spirit writing systems’ across cultures, not only in Africa (Keane Reference Keane2013). Second, African alphabets show an epistemological independence that is greater than was assumed in precolonial and colonial times – or, indeed, as in our case, in the postcolony. Third, African writing systems inscribe the discontent with Western imperialist linguistic impositions and the need to search for identity. For many people in the world, owning their own script, as opposed to having to use one through which they have been oppressed and marginalised, belongs, as James Scott puts it, to the ‘art of resistance’ (Reference Scott1977) or to the ‘art of not being governed’ (Reference Scott2009). This is the case not only because scripts offer the possibility of articulating resistance to the powers who have imposed their own alphabet as a mechanism of control, but also, as Piers Kelly has argued (Kelly Reference Kelly2018b), because very often scripts are made in order to allow people to escape legibility and to hide away from the bureaucratic control of the state, something I also found in undecipherable writing systems in a prophetic movement in Guinea-Bissau (Sarró and Temudo Reference Sarró and Temudo2020). This may sound paradoxical, as the intuitive understanding of writing is that writing systems are concerned with conveying, rather than concealing. Yet, it is clear not only that writing systems belong, at least in their inception, to the arts that reveal and conceal simultaneously (such as masks and other technologies of secrecy), but also that even the putative transparency of literacy in general has to be understood against the backdrop of political persecution, as Leo Strauss argued in his study of Western writing traditions, where he shows how very often the writer has had to master the art of saying while concealing (Strauss Reference Strauss1941).

One could look at the thirst for possessing a distinct alphabet as part of a struggle for recognition, in Honneth’s sense (Reference Honneth1995). Having one’s own alphabet brings equality with the rest of one’s interlocutors. I remember a vignette from Masano ya Mandombe, a Mandombe fanzine produced in Kinshasa, which illustrated a white man who, on seeing an African using Mandombe, said: ‘Oh really? Africans have a writing system after all? In this case we can now collaborate!’

For anthropologists, discussing the invention of writing means remembering an anecdote known as ‘writing lesson’, described by Claude Lévi-Strauss in some of his earliest publications (Lévi-Strauss Reference Lévi-Strauss1948; Reference Lévi-Strauss1955). When Lévi-Strauss arrived at a Nambikwara village in the Amazon and offered some pieces of paper and pens to people, he found that they tried to scribble lines. His anthropological attention was particularly captured by the leader of the village, who took a pencil and started to draw lines in a notepad he had borrowed in such a solemn way that he managed to deceive the others (and perhaps himself) into believing that he too could write, not just pretend to write. Lévi-Strauss used this event to make some pessimistic reflections on writing – much in line with his admired Rousseau. This event has been used by philosophers (most famously Derrida Reference Derrida1967), literary critics (Johnson Reference Johnson1997), historians of writing systems (Lurie Reference Lurie2018), and anthropologists (Déléage Reference Déléage2017) for different purposes. In fact, with due respect to Derridean scholars, it is difficult to make much out of this event because it is nothing more than an anecdote that, as Déléage clearly indicates, raises more questions than it answers. Why did Lévi-Strauss give paper and pens to Amerindians if he thought, as he clearly did, that these people belonged to the category of ‘peoples with no writing’ (peuples sans écriture)? Why did he assume that what they were doing while scribbling – or, better, inscribing – lines belonged to the same category as our concept of ‘writing’? Was he not over-interpreting the scene? Today, inspired by Tim Ingold’s work on the universality of lines (Ingold Reference Ingold2015), we would probably content ourselves with saying that the Amerindians were merely drawing lines. But what were they really doing? Déléage gives very good answers to these questions, or at least gives directions on how to answer them. I believe that the last of these questions is the most important. Why did Amerindians inscribe lines on the piece of paper? Déléage argues that, in South America, traditions of inscription are very old, and he suggests that, in order to understand what the Amerindians were doing ‘from an Indian point of view’, so to speak, we should take these traditions into consideration. This is a point that also applies to African technologies of inscription. We will see that, without being culturalist (I do not want to postulate the primacy of an established culture, whether ‘Kongo’ or ‘African’, on a cultural, but also individual, innovation), we need to place Mandombe in a longue durée framework of Kongo graphic systems (see Chapter 7).

The event that the French anthropologist witnessed is not an isolated case. Writing – the human capacity to translate the verbal into the visual and then back to the verbal – is attention grabbing in its very nature. In history, it has prompted people into either learning to write or pretending they have learned to write by mimetically behaving like those who know how to do it, scribbling lines in notepads to produce what scholars called ‘pseudo-writings’. I have witnessed the phenomenon among Balanta farmers, who, when possessed by an ancestor, write their message on any possible support, very often imitating Arabic script. When they read it aloud, they often do it in glossolalia, which has led some authors to term such pseudo-writings as glossography.

Why are people so intrigued by this technology that they pretend to master it? The fascination with writing is an absorbing topic in itself, and one that brings us to the reciprocal symmetry that, according to many of us, anthropology should possess (Latour Reference Latour2007; see also Déléage Reference Déléage2017). In writing this book, I am trying to answer not only the question ‘Why were the Nambikwara fascinated by a technology they could not understand?’ but also ‘Why was I fascinated by Mandombe as soon as I heard about it, and even more so as soon as I started to see it, even though I was totally unable to read it?’ It is this mutual fascination for the technology of the written word that made me want to know more about how Wabeladio invented Mandombe, and that led me to realise that this was a phenomenon that could throw light on the processes of creativity to which we usually have little access.

One would be tempted to explain the origins of writing systems in colonial or postcolonial contexts according to theories of mimesis. But the case study I offer here shows that Wabeladio did not start by imitating anything. Quite the opposite. He started from scratch with something entirely new and unexpected, something original in the full sense of the word: two graphic elements in the shape of ![]() and

and ![]() , which he singled out on a wall of bricks. From these two elements he invented an unheard-of graphic system that only eventually, more than ten years later, became an alphabet. I think that only by looking at the inventor and his invention from inside, and not with theories from outside that would make him out to be an imitator of other technologies of graphic inscription, can we grasp how it all happened. Wabeladio was an original creator, although his creation did have influences, sources, inspiration, revelation, learning, etc., and in Chapters 8 and 9 of this book I will offer some theoretical reflections on this particular cocktail. I see creators as individuals who realise a ‘double rupture’ (a concept I delve into in Chapter 9). They not only make unexpected combinations of and connections between existing elements that they cut from their original network, to use Strathernian language (Strathern Reference Strathern1999); they also then manage to disconnect the result from the process, presenting it as if it came out of the blue and as if it had nothing to do with previous elements – apart from, in this case, flimsy ones such as two symmetrical cyphers seen between some bricks.

, which he singled out on a wall of bricks. From these two elements he invented an unheard-of graphic system that only eventually, more than ten years later, became an alphabet. I think that only by looking at the inventor and his invention from inside, and not with theories from outside that would make him out to be an imitator of other technologies of graphic inscription, can we grasp how it all happened. Wabeladio was an original creator, although his creation did have influences, sources, inspiration, revelation, learning, etc., and in Chapters 8 and 9 of this book I will offer some theoretical reflections on this particular cocktail. I see creators as individuals who realise a ‘double rupture’ (a concept I delve into in Chapter 9). They not only make unexpected combinations of and connections between existing elements that they cut from their original network, to use Strathernian language (Strathern Reference Strathern1999); they also then manage to disconnect the result from the process, presenting it as if it came out of the blue and as if it had nothing to do with previous elements – apart from, in this case, flimsy ones such as two symmetrical cyphers seen between some bricks.

Forgotten Alphabets

Despite its many advantages, writing has had its enemies too. Rousseau’s ideas on writing, expressed in his ‘Essay on the origin of languages’ (Rousseau Reference Rousseau2000 [1781]), were overall quite critical. Long before him, the ultimate ancestor of Western philosophy, Plato, had already suggested in his dialogue Phaedrus that the invention of writing had perhaps not been such a good idea after all. According to Plato, writing could deter human beings from cultivating memory. His argument was, in fact, much more complex: he was not only worried about the loss of memory per se, but about the ethical transformation of the self linked to oral technologies of learning and transmission, and about the loss of the embodiment of values. This opposition between writing and embodiment resonates with learning dynamics I have encountered in West Africa, where we find a tension between the centripetalism of secrecy and the centrifugalism of writing (Sarró Reference Sarró2022).Footnote 3 I would like to explore further this idea that there might be a counterintuitive association between writing and forgetfulness, because this was very much the rationale underpinning the linguistic epistemology of my first Mandombe lesson in Luanda.

Indeed, what Lei, the Mandombe teacher, wanted us to become aware of was that colonialist practices not only consisted of teaching people to write their native language in the Roman alphabet (which was violent enough), but also involved forcing colonised people to write and read the language of the coloniser and gradually to forget their own languages, thus proving Plato right in his fear of forgetfulness, but in a sense that he would probably not have anticipated. To dig into my West African memories again, in 1994 a very old Baga man in Guinea told me: ‘Our ancestors were illiterate, but they had their own way of recording things.’ He then made a small gesture with his finger on a stick he was holding, as though to indicate that in the past there was a Baga way of inscribing things, of memorising events, on wooden sticks. Abou (my Baga collaborator and the nephew of the old man) and I did not quite understand what he meant. We tried to push him a bit further, but he himself did not really know how the system he was referring to worked. A few years ago, the old man died.Footnote 4

I encountered a similar situation much more recently in the Kikongo-speaking regions of northern Angola. An old man in Mbanza-Kongo told me that, when he was very young, in the early 1940s, his grandfather saw him and a friend write in a school notebook. The grandfather, who lived in the forest and avoided contact with the colonialists as much as possible, said, ‘So this is what they are teaching you at school? We did not need that.’ Then he drew some letters in the sand with a stick, written from right to left, and read them. It was, my interlocutor asserted, a proper alphabet. He told me: ‘I regret not having been interested in it. At the time I did not want to because we thought that writing had to do with witchcraft, but now I know that was the original Kongo writing system, now lost forever, and that many Kongo intellectuals are trying to rediscover.’

One of the characteristics of Mandombe that singles it out from most other known writing systems in Africa is its clear postcoloniality. Indeed, most of the other known alphabets were born in precolonial or colonial times. Unlike them, Mandombe was born in Zaire in 1978, at the zenith of Mobutu’s rule. The political and cultural context is relevant in order to grasp the conditions of possibility for the emergence of a writing system that could claim African authenticity, a notion with special political and cultural value in that part of Africa in the 1970s and 1980s (Callaghy Reference Callaghy1984; Fabian Reference Fabian1996; White Reference White2008). Wabeladio’s biography – which starts, as we will soon see, with his grandfather and his connections to the anti-colonial Kimbanguist church – exemplifies the transitions his country has experienced, from colonial rule through Mobutu’s cultural policies to the rise of ethnic particularism in the post-Mobutu context.

Mandombe is not the only script competing with Roman or Arabic alphabets in the postcolony, however. Perhaps the most successful African script ever is N’Ko, born out of a revelation, like Mandombe, in the Mandingo/Malinké part of French West Africa in 1949 and greatly developed after Mali and Guinea gained their independence. Today, it is widely used in the Mande-speaking zones of West Africa as well as in Mandingo diasporas (Amselle Reference Amselle2001; White-Oyler Reference White-Oyler2005; Wyrod Reference Wyrod2008). As with its West Africa ancestors, the birth of N’Ko took place in areas where Islamic learning met with the Roman alphabet and with indigenous mechanisms of cultural transmission, such as divination, masquerades, and initiation rituals. This was not the case for Mandombe, since Islamic learning is not as prominent a feature of the landscape in Kongo Central as it is in West Africa.Footnote 5 However, there has been a mosque in Wabeladio’s native town of Mbanza-Ngungu for a long time, and one of Wabeladio’s earliest friends and collaborators was a Muslim man who knew Arabic and who later converted to Christianity, though not to Kimbanguism. So, we should not rule out that conscious reflections between the two men on why different religions have different alphabets might have reinforced Wabeladio’s need to convert his initial graphic system into a proper phonological alphabet. Nor should we rule out the fact that Wabeladio may have been influenced by the people, well versed in N’Ko, whom he met in Kinshasa. As I argue, Wabeladio’s sources of inspiration were many – probably many more than I heard about – and although we will get to know a lot about his biography in this book, it is clear that many of the aspects, influences, and motivations of this fascinating person remain to be explored.

On Biography

There is an old saying, attributed to Amadou Hampaté Bâ, according to which ‘in Africa, when an elderly person dies, a library is burned down’. The way this phrase encapsulates notions of archive (as if an individual memory is comparable to a library) has been problematised by some authors (Jones Reference Jones and Carcangiu1993). However, I would like to use it here to highlight the tension between the group and the individual. According to the metaphor, knowledge passed down is collective (a library), and yet when the elderly individual dies the knowledge disappears. The library in the metaphor is a collection of books, not of authors. Despite the number of works dedicated to African individuals and the outcomes of the biographical approach to Africa, far too often Africanist scholars have forgotten about the African author, about the individual who imagined and sculpted the first mask, the woman or man who told the first version of a folk story, or who composed an unknown song, the bold individual who built a house in a different shape to the one in which he or she had grown up, the farmer who singled out a new hybrid variety, or – why not? – the inventor who brought about a new technology of inscription.

Most of the endogenous knowledge in so-called traditional African societies is assumed, at least by a legion of specialists in African studies, to be ‘collective’. We often know the name of the prophet who destroyed the masks and religious icons of a community in an iconoclastic rage. But we do not know the name of the inventor of many of the masks or icons. In fact, before Zoë Strother wrote her book Inventing Masks (Reference Strother1998), not many art historians thought about masks being invented (rather, they were reproduced). Thus, Strother could write that ‘it is the individual who has been far too absent from Africanist art studies’ (ibid.: 24). However, silencing the creator was not at all the intention of the early African art scholars. Many of them struggled against the collectivist misconception and actively looked for the artist underneath the magnificent but often anonymous masterpieces. Some very good examples of this are by Bascom (Reference Bascom and Biebuyck1969) and Fagg (Reference Fagg and Biebuyck1969), both published in an important volume on creativity in tribal art (Biebuyck Reference Biebuyck1969), or the chapters in the volume edited by Warren d’Azevedo (Reference d’Azevedo1973) and dedicated to Melville Herskovits, ‘for whom individual creativity was the essence of humanity’. The fact that Herskovits thought this says something about American anthropology in the first half of the twentieth century, which was undoubtedly much more attentive to individual agents than its European counterparts were.

In the case of the Mandombe alphabet, we are fortunate to know the individual who invented it, and the reader is invited throughout this book to assess the relevance of knowing his story in understanding what this individual achieved.Footnote 6 In Wabeladio’s own view, biography and work went hand in hand, and he thought that one could not study Mandombe without studying his biography at the same time. Wabeladio’s self-consciousness about his history was truly striking; he deployed a distinct subjectivity and an explicit notion of ‘destiny’ that, I suspect, was novel in his era and his social setting. No doubt his education and Christian upbringing helped him develop such an acute sense of self, destiny and péripéties (a French concept I have translated as ‘vicissitudes’). The reader will have to make up their own mind as to how much fact and fiction there is in his biography. By ‘fiction’, I do not mean lies, but rather the skill to narrate things in such a way that every detail in one’s life is made relevant to the completion of the bios as a neatly constructed artefact. This is what Pierre Bourdieu called ‘biographic illusion’, the capacity to externalise oneself as a personnage, a literary character in a well-knitted textuality (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1986; Passeron Reference Passeron1990; Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001; Blanes Reference Blanes2011). No matter how constructed they are, however, biographies are the via regia for African studies to overcome the tendency to neglect the individual or to see Africans mostly as victims and not as actors in their local worlds, a point very elegantly made in the fine biographical studies by Pat Caplan (Caplan Reference Caplan2016).

Wabeladio’s biography is marked by two tensions, which taken together give the narrative he himself built an almost perfect sense of literary suspense. The first tension is that between him and his mother’s authoritarian brothers, which could be interpreted as being a tension between self and society or between individual determination and the expectations of one’s betters. While his uncles wanted him to become a trader, he was determined to study. The second is the tension between Wabeladio’s agency and God’s, between invention and revelation. As we shall see, this tension accompanied Wabeladio his entire life. Did he invent anything or was he the messenger of God’s gift to humanity? As part of this tension, Wabeladio very often downplayed his own agency in order to highlight God’s, but sometimes he did the opposite, and he always introduced himself as ‘Wabeladio Payi, inventor’. That was his social persona. He was an inventor, acknowledged by the state and by society. Yet, he could not deny that his invention was based on a revelation, which rooted it in a transcendent domain. His invention was not the result of a whim or a transitory mental perturbation, but of a command from God.

I see these two tensions as manifestations of a common structure in human personhood. Nearly two decades ago, I wrote an article (Sarró Reference Sarró2005), greatly inspired by Paul Riesman (Reference Riesman1986) and by the notions of Mande heroism (Bird and Kendal Reference Bird, Kendal, Karp and Bird1980), in which I argued that in Africa individuals live in a tension between centripetal forces, which tend to keep them close to the community, and centrifugal notions of agency, which lead them towards individual success and excellence, and often to accusations of selfishness. This dichotomy was particularly acute among the Baga farmers of West Africa, with whom I was conducting fieldwork at the time. I still subscribe to the view I expressed then, except that I would like to highlight the universality of what I was attempting to define. All human lives are subject to the tension between individual imagination and the tyranny of expectation, between oneself as self-made and oneself as made by others. One could ‘Africanise’ Wabeladio’s tension by stressing that, in Central Africa, expressions of individualist intelligence may be accompanied by fears of being accused of occult powers, and certainly Wabeladio was a victim of similar accusations. Therefore, one could argue that revelation could have been a device Wabeladio used to minimise his intelligence and to avoid being socially (or spiritually) punished for his hubris and arrogance. But I do not want to overemphasise this point or to reify notions of ‘African personhood’. In tune with colleagues who have voiced misgivings about too neat an opposition between Western and non-Western notions of personhood (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001; Lambek Reference Lambek2013), I prefer to see the tensions in Wabeladio’s career as local manifestations of universal tendencies, the perils of expressing one’s individuality too assertively, of pitting oneself against the will of one’s family, of being ‘modern’ in the face of received notions of ‘tradition’.Footnote 7 This universality does not mean, of course, that we should not take the local context of the birth of Mandombe into consideration. Quite the opposite. I am a firm believer that only through localised examples can we explore how universal trends express themselves. Let me therefore set out some basic notions about the religious setting against which the emergence of Mandombe needs to be understood.

The Church of Simon Kimbangu and the Spread of Mandombe

Since its beginnings in 1978, the Mandombe alphabet and art have been strongly associated with the Kimbanguist church and are taught in Kimbanguist centres in the DRC, in its neighbouring Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), in Angola, and in the diaspora. A succinct introduction to this church is therefore in order.

Kimbanguism was born among the Bakongo people in 1921, when Simon Kimbangu, a young man educated at the Baptist mission of Wathen (Ngombe Lutete) and often described in colonial sources as a ‘prophet’, started to heal, make prophecies, and even, oral history claims, perform miracles in Kongo Central, then part of Belgian Congo. He became especially famous after allegedly bringing a dead woman back to life on 6 April 1921. This is considered by members of the church today as the official date of the start of his miraculous activities. Why Kimbangu was considered a prophet, and whether he can be sociologically or theologically considered a prophet, is a debate within the Kimbanguist church itself. The official line within the church today is that Simon Kimbangu was the incarnation of the Holy Ghost (Kayongo Reference Kayongo2005); whether he can or cannot be considered a prophet is becoming less and less relevant.

Kimbangu’s fame, as he healed and performed miracles on top of the hill of N’kamba, spread like bushfire throughout the Kongo Central regions. According to some accounts, thousands of people from the entire region, from the French colony of Congo, and from the Portuguese colony of Angola came every day to be healed by him.Footnote 8 People made long pilgrimages on which they delivered or destroyed ritual objects linked to traditional cosmology, in a clear effort to abandon old practices and start a new society afresh. As soon as the movement began on 6 April, the Belgian government – under pressure not only from local authorities but also from Catholic and Protestant missionaries, as well as from merchants who feared that the movement might have a negative effect on their activities – decided to ban it. Kimbangu was taken and imprisoned in September 1921 after two months of fierce persecution in the hills and forests around N’kamba. The Kimbanguist movement, however, continued clandestinely, despite repression by the Belgian authorities (MacGaffey Reference MacGaffey1983; Diangienda Kuntima Reference Diangienda Kuntima1984; Mélice Reference Mélice2009; Reference Mélice2010).

The Kimbanguist church was finally recognised by the Belgian state in 1959, just one year before independence, and it became one of the two major religious institutions in independent Congo under Mobutu’s rule in the 1960s. At present, it is still one of the major churches in the DRC, as well as being a huge international institution. Its members often assert that the total number of Kimbanguists worldwide is around 17 million, but a complete census has not yet been undertaken. Moreover, an internal schism is currently making it difficult to establish precise numbers and memberships (on this schism, see Sarró et al. Reference Sarró, Blanes and Viegas2008; Mélice Reference Mélice2011; Apo Salimba Reference Apo Salimba2013).

The church’s slogan is ‘Kimbanguism: Hope of the World’, and its theology is indeed very much based on messianic hope (Sarró and Mélice Reference Sarró, Mélice, Fancello and Mary2010; Sarró and Santos Reference Sarró and Santos2011; Sarró Reference Sarró, Garnett and Housner2015). It has a political theology centred on the restoration of the kingdom – identified both as the kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Kongo – around the holy city of N’kamba (also known as N’kamba–New Jerusalem). N’kamba was Simon Kimbangu’s birthplace and is today the church’s spiritual and administrative centre, as well as its most important pilgrimage site. Kimbanguism offers a paradigmatic case for the study of political theology and for theoretical comparisons with other messianic-oriented religious communities based on notions of suffering and on the restoration of a divine political kingdom.

In 1960, Kimbangu’s coffin was transferred from Lubumbashi, where he had died nine years earlier, to a mausoleum built in his natal village of N’kamba. In the late 1960s, the Kimbanguist church was inducted into the World Council of Churches, and N’kamba was officially declared the church’s central headquarters. It would be impossible to summarise the current configuration and theology of the church in the space of this chapter, but it is important to emphasise that the suffering of past Kimbanguists is very present in the church’s liturgy and symbolism. Thus, for example, there are said to be 37,000 seats in the main temple in N’kamba, which equals the number of Congolese families who were forcibly displaced and taken away from their homes by the colonial authorities in a futile effort to put an end to the movement.

Today, Kimbanguists form one of the biggest religious communities in the DRC, as well as in the Republic of Congo and Angola. This fact cannot be stressed enough in understanding Mandombe’s widespread acceptance in the public sphere. Over the last 20 years, Mandombe has been used within the church to transcribe biblical and other texts. And, by the time Wabeladio passed away, there was a fierce debate, especially in the DRC, about whether Mandombe should be ‘secularised’ and taught outside Kimbanguist circles too. Wabeladio created the CENA (Centre d’Écriture Négro-Africaine or Centre for the Study of Mandombe) in 1995. Between 1996 and 2012, the CENA created teaching centres (called nsanda) across the national territory, covering the entire Kongo Central, but also parts of Bandundu, Orientale Province, the two Kivus, Equator, Kasai, and many countries outside the DRC. In Kinshasa, each of the 22 local municipalities (or ‘communes’ as they are called) had one teaching centre by the time Wabeladio died. It is probably fair to say that some 10,000 certificates were granted by the different teaching centres over that period. This means that 10,000 people had learned the rudiments of Mandombe by 2012. These rudiments could be acquired in three months by literate people but could take up to six months if the students did not know how to read or write. Mandombe teachers were always connected to professional pedagogues so as to improve their teaching techniques. ‘For those who are literate, we explain the principles of Mandombe, but for those who are illiterate, we teach them to draw without any theory whatsoever,’ one of the teachers explained in an interview in 2012. There was never a shortage of teachers: one thing learning Mandombe did was to encourage people to become teachers of the alphabet.

In a tour I did with Wabeladio across Kongo Central in summer 2012, I noticed the enthusiasm of some elderly people in truly remote places in the forests of Mayombe who, while being illiterate in the Roman alphabet, could nevertheless write and read in Mandombe (although I did not find anybody who could read with fluency). I was equally, if not more, impressed by the enthusiasm of young people who worked in their own cassava field and orchards in the nsanda on a cooperative basis. The different nsanda I visited in the urban and rural areas that year in Kongo Central – including Mbanza-Ngungu, Kinsantu, Kimpese, Matadi, Boma, Muanda, and several small forest villages between Boma and Tshela – were all quite large, and in some of them I was received by 30 or 40 people. The word I heard most often when asking why they were learning Mandombe was ‘identity’. Mandombe was an alphabet sent by God to a Mukongo man, and it was their duty and pride, as Bakongo, to learn how to read it and write it.

Despite such enthusiasm among huge numbers of people, however, not all of them used Mandombe. As Wabeladio explained to me, a lot of people learned it, but they very rarely used it and ended up forgetting how to. In order to encourage people to keep using it, the Mandombe League was created in the late 1990s. This encouraged Mandombe users to write to each other; because postal workers could not be expected to be able to read an address written in Mandombe, these letters were sent through the CENA itself. They were taken from the nsanda in the sender’s village to Kinshasa; from Kinshasa, they went to the nsanda in the recipient’s village. This allowed people at the headquarters in Kinshasa to keep tight control of the Mandombe League’s progress. Up to 2012, they were very happy with the huge number of letters that were circulating among the different centres every year. The League also organised social visits to help people get to know each other. In 2011, for instance, Wabeladio hired a van in Kinshasa and took many Mandombe students to pay a friendly visit to some nsanda in the southern province of Bandundu.

In 2012, I was invited to a nsanda in Kimpesse. One of the young women I interviewed there promised that she would send a letter in French using Mandombe to me in Oxford. A few months later, an email arrived with a scanned document. It was the promised letter. I reproduce it here as it contains no confidential information. I include it not only as a token of Mandombe, but also to show that it can be used to transcribe French, not only Kikongo or Lingala (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 A letter in Mandombe sent to the author as an email attachment in 2012.

The Inventor and the Invention

In writing this book, I want readers to reflect on the relationship between revelation and invention, on the difficulties of telling the difference between inner originality and external influences and ‘diffusion’, and on the interconnections between the individuality of creators, their culture (in this case, ‘Kongo’ culture), and their society. These three themes, together with the legacies of the Kimbanguist prophetic culture, structure the chapters to follow.

The main chapters of the book are divided into two parts, closely following the structure that Wabeladio and I designed when we started working on it together. Wabeladio was quite adamant that the first step for anyone who wanted to know about Mandombe (including learners of the alphabet) should be to hear the story of the revelation – that is, how the alphabet descended upon him, and how he developed the revelation into a graphic system and a form of art. Therefore, we spent many hours visiting and revisiting every episode of his eventful life; I am happy we did so, as I doubt that anybody else, apart from his widow, has so much first-hand knowledge of that life as I do thanks to his trust. I have tried to keep as close to Wabeladio’s own words as possible, although I have considerably shortened the biography, as suggested by several readers, since the connections between some of the events he saw as relevant and Mandombe itself would require too much explanation. The recounting of these events constitutes Part II of this book.

Part III, written after Wabeladio passed away in 2013 (but using a lot of the rough material he passed on to me), shows that the process of invention was even more complex than the biography suggests. While Part II illustrates a life full of events, the subsequent part shows that a steady, consistent process of invention was taking place in Wabeladio’s mind. Wabeladio’s invention depended very much on the combination of what he perceived as revelation and his own determination to materialise that revelation into something that people would find useful. I call this combination ‘prophetic imagination’ and hope to demonstrate that, in Wabeladio’s case, this imagination was the result of a very long process of trial and error, incubation and rethinking, and responses to critical feedback offered by various publics. Wabeladio gave hundreds of lectures all over the world about how he invented Mandombe and about the connection between invention and revelation. Because the lectures would rarely run over an hour, his condensed version of events always gave the impression that the invention was a flashbulb breakthrough, a sudden insight that occurred overnight, or, at most, over a few months. Only little by little was I able to discover that the process of invention was a very long one. Not only did it take decades, it was also ongoing when Wabeladio died. This gradual aspect of invention – in sharp contrast to the sudden, ‘eureka-like’ aspect of its presentation – is often discussed in the literature on invention and creativity (Gruber Reference Gruber1974; Wagner Reference Wagner1975; Eysenck Reference Eysenck1995; Csikszentmihalyi Reference Csikszentmihalyi1996). Most of humankind’s inventions and discoveries have been marked much more by trial and error than we know, and even sudden inventions are preceded by sometimes very long periods of ‘incubation’, as a large body of theorists on creativity from Rollo May (Reference May1975) to Kounios and Beeman (Reference Kounios and Beeman2015) have shown. More specifically, Smalley et al. (Reference Smalley, Vang and Yang1990) have evidenced that inventions of writing are less abrupt than their inventors have often claimed. We have difficulty in accepting this processual aspect of invention because we all believe in the romantic myth of the genius being suddenly illuminated (Robinson Reference Robinson2010).

It is true that in some societies creative geniuses have to be possessed by a spirit or goddess in order to break with the imposed ‘patterns’ of culture and create something new. Lévi-Strauss (Reference Lévi-Strauss1995: 168), for example, reported that, among the North Americans, possessed women invented new geometrical weaving patterns while others simply copied. In many ways, this is exactly how Wabeladio presented his own nature as a Kongo cultural innovator to his audiences: one day Simon Kimbangu visited him in a dream, and the next he invented a writing system – just like a possessed Native American weaver inventing a new pattern. Because we all believe in, to cite Lévi-Strauss again, ‘the cliché of the damned painter or poet, with all its pseudo-philosophical developments on the links between art and madness’ (ibid.: 169, my translation), we accept that such abrupt innovations are perfectly possible. But the Native American weaver metaphor is misleading if taken as a general image of cultural innovation. More often than not in recorded history, geniuses, inventors, and creators took their time to think, and they often made mistakes in the process. The short duration of Wabeladio’s presentations did not help; he always had to condense more than 30 years of research into a few minutes. In longer conversations with me, he was quite honest about how long it took him to invent – or, I should say, develop – Mandombe. Rather than diminish his genius, I hope that the unveiling of the hard work involved in the invention of Mandombe explored in the following chapters will highlight the intelligence and originality of Wabeladio Payi as an inventor, as well as throw light on the nature of human invention.

The fact that he associated himself so intimately with the label of ‘inventor’ suits phenomenological theories of invention (e.g. Boirel Reference Boirel1961), according to which what characterises invention is not so much the technical ability to make or unmake things, but the intentionality, the particular attitude the inventor has towards the world, whatever his or her specific inventions are. Wabeladio invented many things, although he is famous only because of the alphabet. Yet I need to stress that, in my interpretation at least, he reinforced his inventive attitude with a strong faith in God and in Kimbangu. We cannot dissociate science from religion or invention from revelation in Wabeladio’s life and work. For Wabeladio, God, numbers, and letters were intimately associated in such a way that his life and work, as well as the derision to which he was often subjected, remind me of the self-taught mathematician, and deeply religious man, Srinivasa Ramanujan. An Indian genius who worked in Cambridge with the mathematician G. H. Hardy, Ramanujan shows how intimately religion and science can coexist in certain minds, to the bemusement of certain others (Kanigel Reference Kanigel1991). An analysis of Wabeladio’s life and works helps us critically re-examine the epistemic fields under which we study creative, scientific, and religious processes.

Given that Wabeladio was not with me when I gave final shape to a book that was originally going to be a collaborative work, I lost the essential guiding insight to bring the structure of Mandombe and the biographic progress of its inventor together. Thus, the two parts of the book are different in style. We had completed a draft of Part II, on Wabeladio’s biography, and were starting to tackle the following section, on the structure of Mandombe and Kimbangula (the art based on Mandombe), when Wabeladio passed away. The difference in styles reinforces the difference in topics. The book probably looks like the stem of the plant offered as an image by the founder of modern linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure, in his 1916 Course in General Linguistics (Saussure Reference Saussure2011 [1916]). While Saussure used the image to illustrate the difference between synchrony and diachrony in spoken language, I think it is also particularly apt in thinking about the evolution and structure of writing systems. Saussure explains:

If we cut crosswise through the stem of a plant, we can observe a rather complex pattern on the surface revealed by the cut. What we are looking at is a section of the plant’s longitudinal fibres. These fibres will be revealed if we now make a second cut perpendicular to the first. Again, in this example, one perspective depends on the other. The longitudinal section shows us the fibres themselves which make up the plant, while the transversal section shows us their arrangement on one particular level. But the transversal section is distinct from the longitudinal section, for it shows us certain relations between the fibres which are not apparent at all from any longitudinal section.

In tune with this image, the biographical part of this book shows the vertical temporal fibres, the vicissitudes of Wabeladio across time, while Part III shows the ‘complex pattern’ of Mandombe itself. Anthropologists know that the relationship between structure and process is not as clear-cut as the structuralist image suggests, and in many ways our discipline has consisted in showing that, if process sediments in structures, structures give directions and meaning to processes. This, as Marshall Sahlins has so well demonstrated (e.g. Sahlins Reference Sahlins1981), applies to historical processes, but I would posit that it applies to biographical ones too.

Chapters 2 and 3 of this book therefore show the fibres of the biography of Wabeladio as he told it to me, with some clarifications I obtained from other interviewees either with him or on my own after he passed away. However, I did not want to double-check too much and render a 100 per cent ‘objective’ account of events, as what is relevant for my purposes is Wabeladio’s own perception of his biography: the way he inscribed it in his invention, and how he recalled and considered significant some specific moments in the history of postcolonial (and, at the beginning of the narrative, even colonial) Congo/Zaire. I was unable to finalise it with the approval of Wabeladio as he passed away before I had transcribed our many hours of conversation. Many of the events Wabeladio reported were difficult for me to take at face value, although I never doubted his conviction that this was how things had happened. In fact, every time we could double-check an event with someone who had witnessed it or participated in it, as we often did in the DRC, Wabeladio’s memories proved to be very accurate, and I believe that there is no justification for doubting anything. In some moments, however, especially when things lean towards the supernatural, the reader will have to make up their own mind as to whether to believe it or not. I have made an effort not to sound hagiographic, but at the same time I did not want to silence Wabeladio’s conviction that there was something rather unique in his life: a sense of having been chosen for an important, educational, and messianic mission.

In Chapter 4 the biography continues, but the writing is quite different, as we move into the times when we met and, inevitably, I become part of Wabeladio’s life story. In the summer months of 2011 and 2012, I went to Congo to collect data on Wabeladio and on Mandombe, and we travelled around the country (Wabeladio gave some talks in Lubumbashi in 2011 and in Matadi and Tshela in 2012). We also undertook the pilgrimage from Mbanza-Ngungu to the sacred city of N’kamba (around 55 kilometres) twice. These journeys, which are particularly dear to me and now feature in my own biography, proved to be very useful in helping me to fully and intimately grasp the connections between specific places where Wabeladio had his first revelation in 1978 (places full of historical significance for Kongo subjects) and the nature of his invention.

Part III offers, to continue with Saussure’s image, a transversal cut that shows the intricate structure of the alphabet and of the art Wabeladio invented. Chapter 5 discusses the technicalities of the geometry underpinning the alphabet, while Chapter 6 focuses on the art. Chapter 7 offers some reflections on how successfully Wabeladio managed to root his invention in Kongo culture and identity, while Chapter 8 analyses some unpublished material by Wabeladio that testifies to the fact that the creative process of Mandombe and the attribution of sounds to graphic elements were very complicated. We may never fully understand this process unless more unpublished material emerges. Nevertheless, the example discussed here presents evidence of how a particular writing system emerged in a way that will no doubt interest scholars of graphic systems, as the degree of documentation we have for Mandombe is rare in the study of the appearance of writing systems.

In order to grasp fully the way in which Mandombe came into existence, we need to consider the constant rethinking of it throughout Wabeladio’s life. It was not a sudden eureka moment of inspiration but the outcome of a very laborious process, in which many influences operated, and constant revisiting was necessary. In order to analyse how Mandombe was invented, how it was accepted by its various publics, and how it evolved, we need to bring together some Kongo cosmology, some geometry, some linguistics, and some theories of inspiration and invention. But first of all we need to listen to Wabeladio and pay careful attention to how he told us about his life. This is where we part company with Saussure. For Saussure, language could be adequately studied through the transversal perspective: knowledge of the history or etymology of words is unnecessary when studying their synchronic relationship within living languages. But Parts II and III of this book, the biographical and the socio-cultural, the processual and the structural, invention and reception, are entirely dependent upon and complement each other. This book is not only, or even essentially, a study of an African writing system. Rather, it is an extended reflection on the nature of creativity and innovation, both as human capacity and in relation to the socio-cultural ground from which they arise.