Introduction

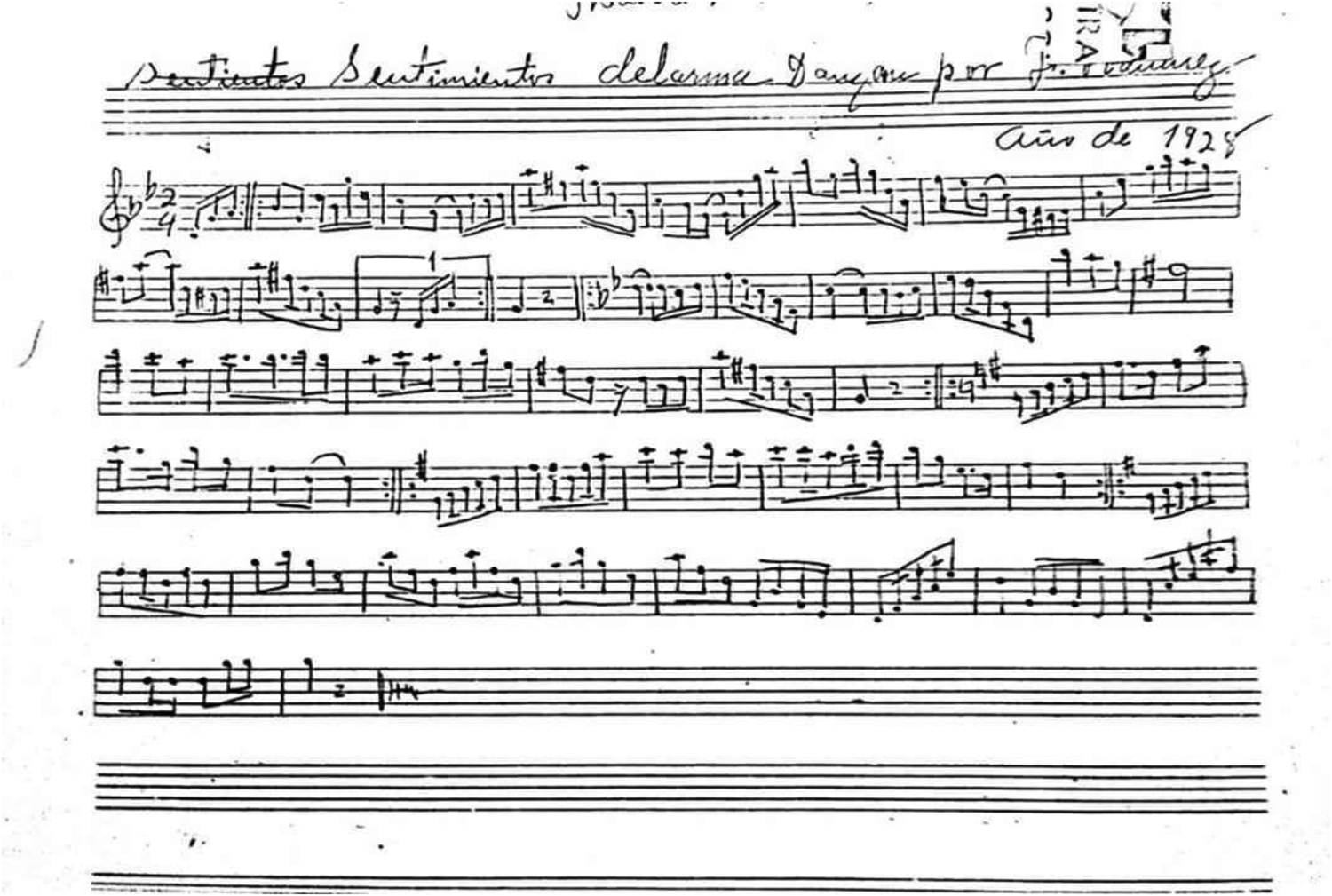

‘That's the stroke that binds it all’, says master percussionist Joaquín Chávez as he addresses an audience made up largely of music students, ‘all the band listens for it and they all hang from it’ (Chavez 2017). The stroke Chávez refers to is the second crotchet of the baqueteo, a pattern which usually accompanies the verse section, or canto of a típico song, and which ties típico to a rich history of cultural dialogue in the Caribbean. Típico is the common term for a popular dance genre in Panama, practised by accordion-led bands called conjuntos (González Reference González2015, pp. 22–3, 145).Footnote 1 ‘Dancers may not know it’, continues Chávez, ‘but they all hang from that beat, too’ (Chávez Reference Chávez2017). Chávez is one of the most highly regarded timbaleros among típico performers. He plays with Los Patrones de la Cumbia, the conjunto led by accordionist Sammy Sandoval and his sister, the singer Sandra, who are among the most on-demand típico performers in Panama. Their current place in Panamanian popular music was first studied by ethnomusicologist Edwin Pitre-Vásquez (Reference Pitre-Vásquez2008), whose ground-breaking study on típico remains a fruitful reference. Los Patrones are known for innovations which seem to break from ‘traditional’ típico, frequently borrowing from other urban Caribbean genres – from son to reggaeton and much in between. Yet, in spite of their apparent diverse musical influences, the group remains closely connected to a tradition which stems back to a generation of violinist–composers born at the turn of the 20th century who set the bases for what is now regarded as Panamanian ‘traditional’ music – the term used here to denote a corpus which is widely accepted to be foundational of a ‘national’ music.Footnote 2 Among the main figures of this generation of creators is Francisco ‘Chico Purio’ Ramírez (1903–1988), author of several of the most celebrated dance pieces of the Panamanian music repertoire. Arguably the most iconic among them is ‘Los sentimientos del alma’ (‘Feelings of the soul’, 1928, see Figure 1),Footnote 3 a piece which helped to define the danzón–cumbia genre. I will propose below that the culture of innovation, adaptation, adoption and reinterpretation of tradition in modern típico is strongly linked to the history of Panamanian popular dance music, which is itself the result of a diverse Caribbean cultural dialogue (Matory Reference Matory, Appiah and Gates2005). I will likewise explore how the Cuban danzón, acknowledged by Melissa González (Reference González2015) and Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2021) as a strong influence on típico, was quite popular in Panama from a time before previous researchers have hitherto recognised in scholarship – indeed, evidence shows Panama even exported their own danzones to the Caribbean and beyond from the earliest days of recorded music. This exploration will enable us to significantly broaden our understanding of the complex matrix of currents which forged modern típico during a time of profound social change in Panama.

Figure 1. Autograph score for ‘Los sentimientos del alma’, reproduced with permission (private collection, Ramírez family).

I will trace the prehistory of típico through the contributions made by the pasillo–waltz complex, the Cuban danzón and the Panamanian cumbia in order to show how these coalesce in the music of Chico Purio and his contemporaries, whom I collectively call the Azuero School. I approach, comment on, and expand the work by musicologists Edwin Pitre-Vásquez (Reference Pitre-Vásquez2008), Melissa González (Reference González2015) and Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2015, Reference Bellaviti2020a, Reference Bellaviti2020b, Reference Bellaviti2021), particularly in regards to the rhythmic aspect of típico and the central role of the timbal, through analysis of data from my ethnographic research and study of the recorded repertoire. Foundational literature by Narciso Garay (Reference Garay1930) and Manuel Zárate (Reference Zárate1962) and the work of folkloristas such as Eráclides Amaya (Reference Amaya1997), Juan Antonio Vargas (Reference Vargas2003) and Milciades Pinzón (Reference Pinzón2018) are also addressed as part of my discussion.

The introduction and creolisation of European dances, the thriving danzón culture in Panama City since the late 1800s, the advent of radio, the introduction of the accordion, and the acknowledgement of the danzón–cumbia as a unifying ‘Panamanian’ musical genre – in spite of a complex reception history (González Reference González2015; Bellaviti Reference Bellaviti2020a) – contributed to the development of típico as a distinct popular music genre, separately from the Colombian cumbia. A mixture of mixtures, típico is the result of the amalgam of cultural elements coexisting in Panama in the first decades of the 20th century and part of a Caribbean cultural dialogue. While catering to a discreet audience within Panama, accordion-led típico is perceived by many locals today as a truly ‘Panamanian’ music, connected to the country's history and paradigmatic in reference to its traditions. Before I discuss how tributary elements helped to shape modern típico, it is important that we first explore how each of these made their way to Panama and the context in which these cultural practices exerted influenced on, and were influenced by, established local traditions during a crucial time in Panamanian history.

Panama's role as a logistical hub in colonial times was reiterated during the California Gold Rush, when numerous travellers crossed the isthmus. This prompted the building of the Panama Railroad, a feat which required foreign labour (McGuinness Reference McGuiness2008). Not a half-century later, Ferdinand De Lesseps began his ill-fated attempt to build a canal across Panama, and many more workers arrived from the Antilles, Europe and Asia. Finally, as the French effort subsided, the United States took over the construction of the waterway while Panama declared itself a sovereign nation. It was soon after this time of social–political change and copious immigration that the predecessor of típico, the danzón–cumbia, developed from an active dialogue among diverse cultures from across the Atlantic, but also between local social circles, through dance and rhythm.

The Panamanian pasillo: a unifying dance

The pasillo, a creolised Panamanian version of the waltz, contributed in various ways to the development of a modern dance culture which led to the advent of típico. Like the also widely popular European waltz, the pasillo is a dance that does not require complex choreographies like other dances, such as the quadrille. This allows the pasillo to be learned and performed across social circles, which is particularly relevant in an age where social mobility is effervescent in Panama.Footnote 4 Consequently, the pasillo brought the richness of harmony and structure of European salon dances to a wider public. While a descendant of the waltz, the pasillo retained its own identity and was performed together with waltzes at least through the first decade of the 20th century (Moreno de Arosemena Reference Moreno de Arosemena2004). Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2021, pp. 33–5) argues that the sectional nature of the danzón, itself influenced by European dances, is most responsible for the structure of the danzón–cumbia. However, the fact that the waltz and the pasillo – both featuring sectional structures, contrasting sections in related keys and couple dancing – had already become quite popular in Panama City and in the countryside points to an earlier introduction of these features into Panamanian musical consciousness. Furthermore, the pasillo culture in Panama is intimately linked to the danzón–cumbia, as several of the Azuerense composers and performers known for danzones–cumbia also composed pasillos, and both forms were played in private house dances in coastal towns of Azuero and in Veraguas (Ramírez, E. 2021, 19 November, personal communication (Purio, Panamá); Ramos, C. 2021, 26 August, personal communication (Santiago, Panama)). I will discuss below the musical ways in which the interchange between European, Caribbean and local elements in the context of the Panamanian cities and towns constructed the platform for the discontinuous cultural dialogue which developed into Panamanian típico.

In Panama City, social mobility between classes was frequent in the 19th century and the waltz became a platform for inclusion and participation (White Reference White1868, p. 89). Even though Panamanian urban society remained strongly divided between the elite and the lower classes after the 1821 independence from Spain, military and civil service, as well as successful commercial activity, were common platforms for advancement (Figueroa Navarro Reference Figueroa Navarro1978). In the hinterland and countryside, the waltz was enjoyed in balls, where it framed local dances such as the punto,Footnote 5 but also European ones, like the polka and the mazurka (Porras Reference Porras1882/1944, p. 14). The popularity and cross-cultural performance of the waltz allowed for it to be influenced by rhythms and social practices already established in many cultures in the Caribbean and South America (Riedel Reference Riedel1986; de Jong Reference de Jong2003; Gansemans Reference Gansemans and Kuss2007). Local dances were in turn enriched by the harmonies and formal structure of European waltzes, as is evident from the harmonic structure of the earliest Panamanian pasillos on record. The waltz, as attested to by several sources, was practised commonly in Panama even before the danzón coalesced into a definitive dance form. Certainly, notwithstanding, other popular sectional dances practised in the 19th century on the Isthmus also contributed to the structural development of danzones–cumbia – Jenny White mentions, for example, the Czech redowa together with the polka and the waltz (White Reference White1868, p. 89) played by a local band in Panama City led by Miguel Iturrado (+1879), a prodigious Panamanian violinist and composer, nicknamed Paganini for his prowess on the instrument (Garay Reference Garay and Demóstenes Arosemena1915, p. 213). A number of composers of pasillos were active in Panama City from the 1860s, including Frenchman Jean Marie Victor Dubarry, Lino Boza from Cuba and Isthmian bandleader José Suárez. Jaime Ingram notes that these musicians, along with those of the following generation, also composed waltzes, polkas and marches (Ingram Reference Ingram and Castillero Calvo2019, pp. 456–7). The pasillo developed into a distinct dance form and musical genre toward the end of the 19th century in Panama, Colombia and Ecuador, in a process which parallels that of the Cuban danzón. The first known notated pasillos in Azuero come from the beginning of the 20th century (albeit only melodies and mostly in manuscript), and also from this period are the first clear written descriptions of balls where the dance is featured.

Celia Moreno de Arosemena recalls an account from a ball held in celebration of the 1907 inauguration of the Governor's Palace in La Villa de Los Santos, at that time the capital of Los Santos province in the Azuero peninsula. National and local authorities were present at the event together with the town's elite. ‘The organisers, with anticipation and under the highest zeal, procured the main musicians from the town’, writes Moreno de Arosemena (Reference Moreno de Arosemena2004, p. 255). The group was formed by two violinists, two guitarists, a flutist, a contrabassist, a triangle player and three drummers.Footnote 6 The ball at La Villa de Los Santos proceeded in customary fashion, with waltzes framing polkas, mazurkas and a pasillo ‘whose lively notes had a je ne sais quoi that filled listeners with joy’ (Moreno de Arosemena Reference Moreno de Arosemena2004, p. 256). While the main ball progressed, a second ball was being held in a nearby open-air venue. This alternative event was open to the larger public, specifically those without access to upper class socialisation. There, a more rustic dance music was performed, along with spontaneous tamborito. The tamborito is a song and dance genre where one or a group of percussionists accompany a lead female singer, called cantalante, and a chorus of women who sing in call and response (Robles Reference Robles2022, pp. 4–5). When the formal ball ended, Moreno says, revellers decided to continue celebrations and moved to the popular dance, where ‘[t]he party concluded with the first morning light’ (Moreno de Arosemena Reference Moreno de Arosemena2004, p. 257). This event, which came to be known as the ‘Ball of the hundred lights’, is but one example of the degree to which musical cultures from the elite and lower classes coexisted and influenced one another at the turn of the century in Azuero. It also reveals that by 1907 the pasillo was already a well-established, respected, distinct dance form, separate from the European waltz.

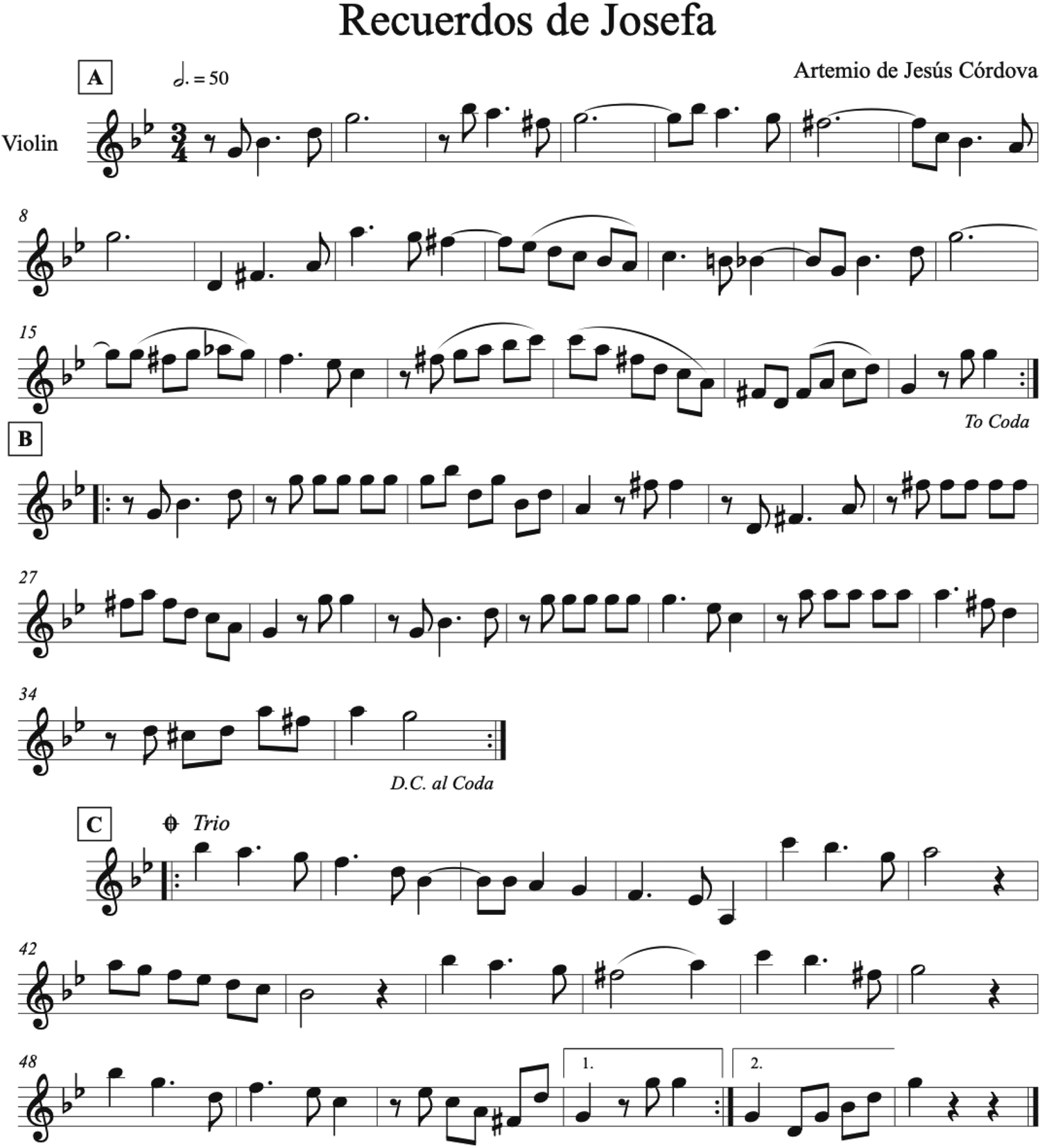

Below is one of the earliest notated Panamanian pasillos from Azuero, ‘Recuerdos de Josefa’ (1917), composed by flutist and violinist Artemio de Jesús Córdova (1896–1988, see Example 1). The first AB section is in G minor, followed by a contrasting trio which begins in the relative. This sectional structure with modulation can be found in danzones–cumbia by both Córdova and later Azuerense musicians such as Francisco Ramírez and Escolástico Cortez. Pasillo melodies are often nostalgic like this one, but can also be cheerful and playful as exemplified by the well-known ‘Suspiro de una fea’ (c. 1940) by Vicente Gomez Gudiño.

Example 1. Recuerdos de Josefa from an autograph copy by Artemio de Jesús Córdova. Reproduced with permission (private collection, Segistán-Córdova family).

In a performance of Panamanian pasillos, we can hear a rhythmic accompaniment similar to that of the Antillean waltz (Gansemans Reference Gansemans and Kuss2007, p. 442), which effectively generates a two-dotted crotchet pattern, while still preserving a ‘waltzy’ feel of one pulse per bar. Panamanian violinist Luis Casal recorded ‘Recuerdos de Josefa’ using the same instrumentation described by historical records and in a style informed by early recordings such as Panamanian tenor Alcides Briceño's 1928 pasillo performances of ‘Deseos’ (Victor 81933) and ‘Corazón’ (Columbia 3249-X), as well by as extant scores. Casal's rendition is a useful tool for understanding the rhythmic complexities of the dance, as well as the harmonic structure of the form, which are not quite evident from the melodic score alone. The compound accompaniment is juxtaposed against a melody organised in triple time, creating a polyrhythmic feel which provides a sense of ebb and flow to the music. While the ‘feel’ is in one, like a waltz, the n E e q pattern generates an agogic accent at the end of the bar, which propels the flow of the music to the next bar – as we will see below, this is a relevant feature of modern típico patterns. This isorhythm can also be observed as the underlying base of two of the main drumming airs in Panama, the tambor corrido and the atravesao (see Example 2). The accompaniment of Panamanian pasillos at the beginning of the 20th century frequently involved drums. According to accounts from surviving musicians like those recalled by violinist Simón Saavedra,Footnote 7 a rhythmic pattern similar to the tambor corrido mentioned above would have been used to accompany the earliest pasillos, as it is today. The same drums and patterns which were used for cumbias and tamboritos were also used for salon dances and, quite importantly, the same musicians as well (Moreno de Arosemena Reference Moreno de Arosemena2004; Saavedra, S. 2021, 1 July, personal communication (Guararé, Panama); Ramírez 2021, personal communication; Ramos 2021, personal communication).

Example 2. Panamanian drumming airs in 6/8.

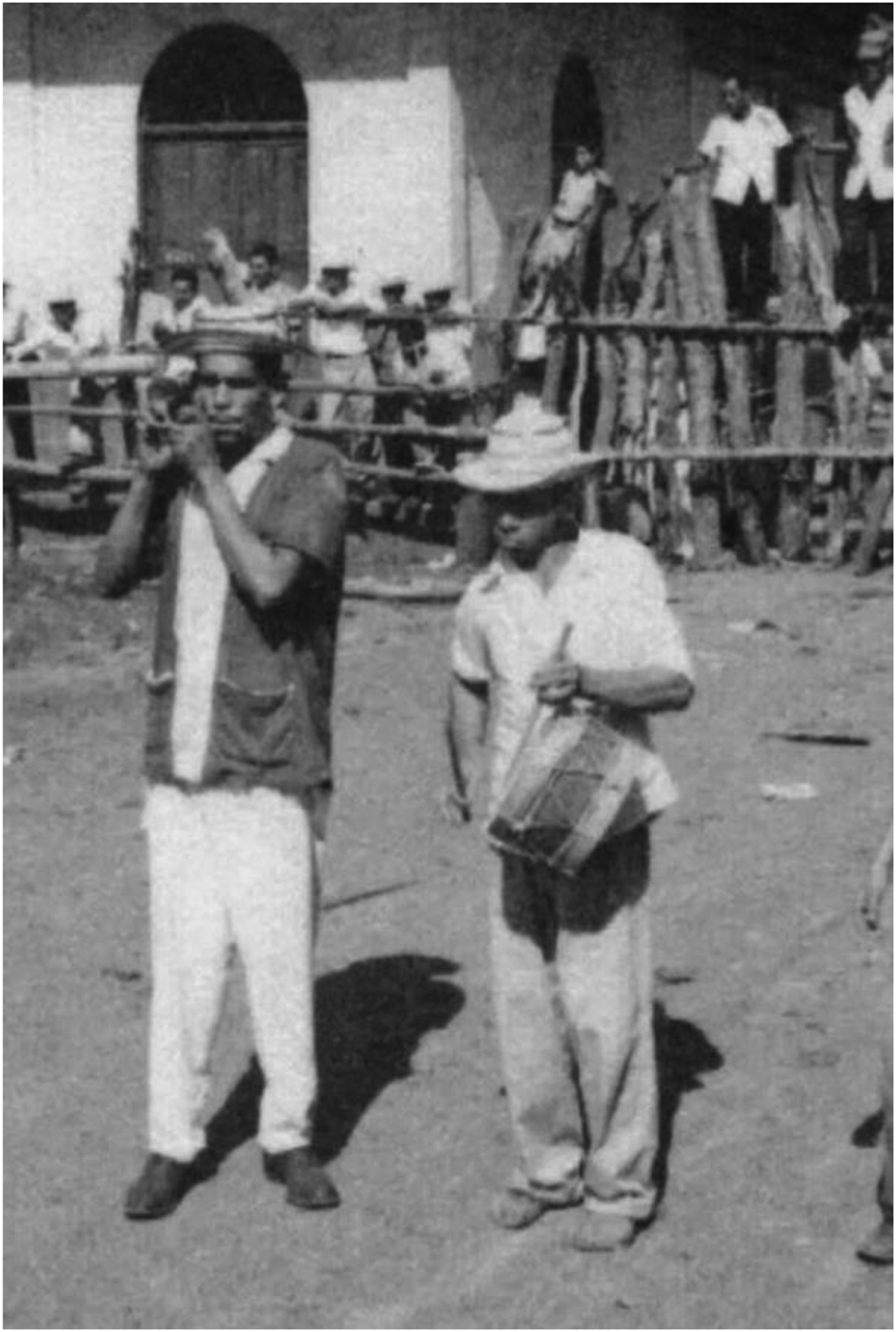

In the case of Azuero, the percussion accompaniment included single-headed conical drums as in all Panamanian drumming traditions,Footnote 8 as well as a drum of European ancestry with profound implications for the development of modern típico: the caja santeña (‘Los Santos snare drum’). The caja santeña is a double-headed membranophone played indirectly on one of its goat or deer drumheads (see Figures 2 and 3). A set of gut snares is affixed against the other head. These snares vibrate against the resonating head in much in the same way as early modern Iberian, Swiss and German military side drums. There are three important differences between the caja santeña and other Panamanian double-headed membranophones. First, other cajas are played on both heads and have no snares. A second difference is the way in which the heads are fixed: larger cajas from Darién or La Chorrera lack rims, the heads being affixed directly to the body of the drum by rope. The caja santeña, on the other hand, has wooden rims on both sides which are then tightened with rope to fix each skin, in turn tucked with a flesh hoop in order to generate tension. A single rope is used which, after securing the heads and rims, becomes a shoulder carrying strap – this brings us to the third difference, the manner of playing. Larger rimless cajas are placed on their sides either on the floor or on a pedestal, and played indirectly with a hand on both heads (like a Dominican tambora). The caja santeña is carried from the shoulder on the drummer's side; players are then free to walk and perform in the same manner as military drummers. This is a significant difference, since it makes the caja santeña a readily portable instrument in contrast with other Panamanian cajas, allowing performers of this region to play while walking with carnival tunas (Zárate Reference Zárate1962, pp. 89–90) and religious processions, as its military predecessors did alongside marching troops in training and in battle as signalling devices.

Figure 2. Caja santeña and pito, at the bullfight during the Mejorana Festival in Guararé, ca. 1960. Photograph: Patronato Festival De La Mejorana.

Figure 3. Caja santeña. The right panel shows the gut snares affixed to the bottom resonant drumhead. Photographs by the author.

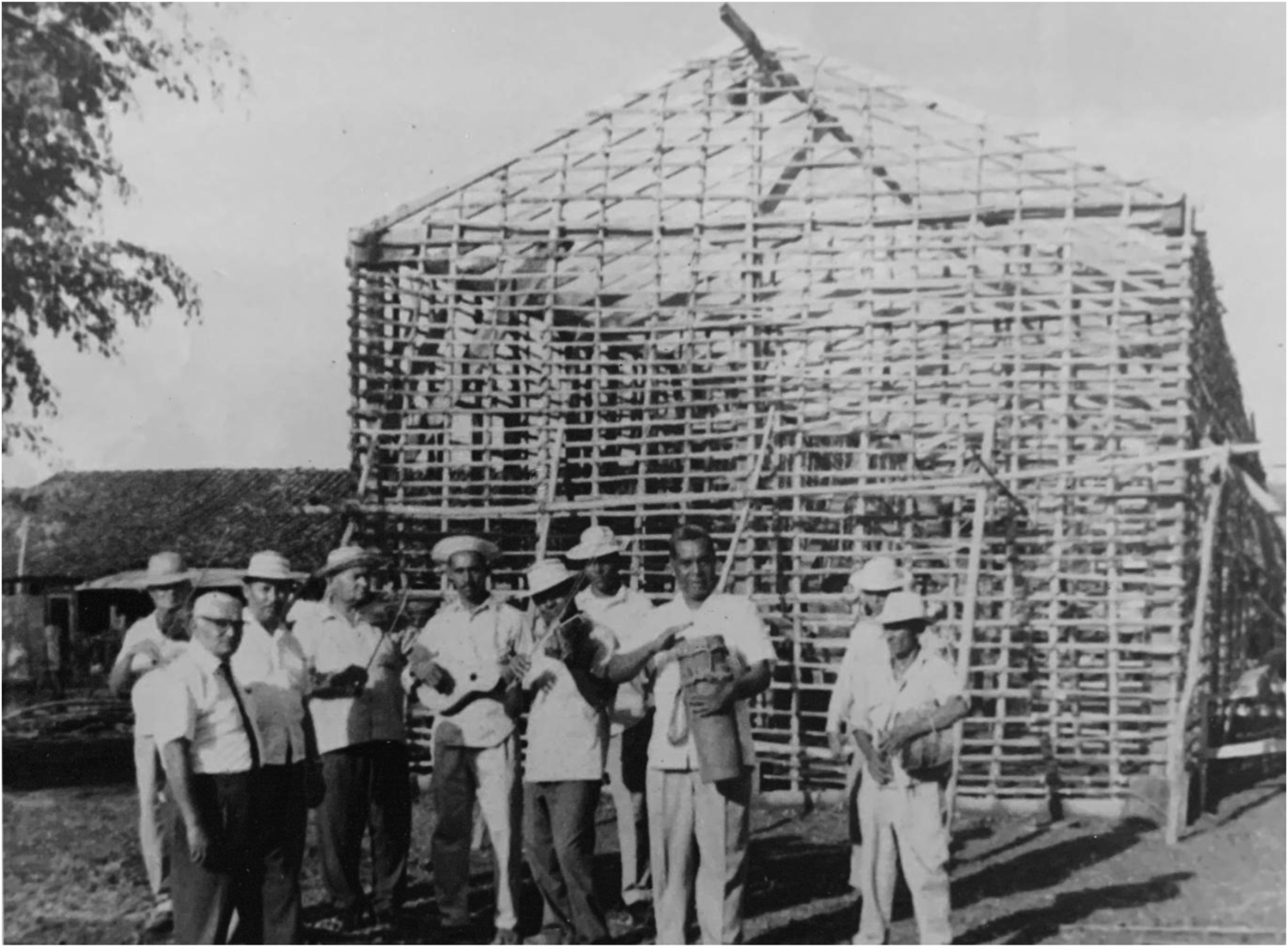

Portability meant that cajeros from Azuero could then accompany processional music in religious and secular celebrations as much as they did pasillos, waltzes, polkas and other salon dances while sitting down indoors. Violinists, likewise, played in formal balls, popular tamboritos, juntas de embarre (mud-walled house-building celebration, see Figure 4), and in religious services both within the church and in procession. Violinist Manuel José Plicet (1869–1967) is remembered by Moreno de Arosemena as a staple during Sunday service and Feast Days at St Athanasius parish in Los Santos. ‘Manojo,’ as Plicet was affectionally known, would lead the congregation in music as he ‘played the violin and sang at the same time’, but could also be found in secular celebrations both formal and spontaneous (Moreno de Arosemena, Reference Moreno de Arosemena2004, p. 161). Professor and Los Santos Museum director Manuel Moreno (1 July 2021, personal communication, La Villa de Los Santos, Los Santos) recalls listening to ‘Manojo’ Plicet in church as well as during Corpus Christi parades, accompanied by drums – his son, Tobías, became a famous pasillo and traditional violin composer and performer. Violinists, like drummers, served as bridges between the salon and the street, generating nuanced connections through melodic design and rhythm. Whether parading with a merry tuna during carnival celebrations (Sáez Reference Sáez2008, p. 45), accompanying Corpus Christi dances, or in spontaneous gatherings in Azuero's characteristic front porches (Moreno 2021, personal communication), violinists and drummers were there, seamlessly bringing together traditions from European salons and churches with creolised drumming and melodic gestures from cultures across the transatlantic circuit.

Figure 4. Violinists and drummers during a Junta de Embarre in Guararé, ca 1968. Photograph, courtesy of Casa Museo Manuel F. Zárate, Guararé.

Even though the pasillo is now almost exclusively performed in the contexts of preservation and nostalgia, ramifications from its performance practice and cultural dialogue in Azuero persist. The violin is still regularly used today in Panama alongside drums in religious and secular contexts. They can be heard in tunas, at the Parade of the Thousand Polleras (see Figure 5) and the Desfile de Carretas at the Festival de la Mejorana, for example.Footnote 9 Religious celebrations where the violin and drums are prominent in parade include the Cristo de Esquipulas pilgrimage in Antón, the translation of Saint Images in North Coclé and the Cucuá ritual-game. Similar violin and drum practices, stationary and on the move, are not uncommon in the region. The ‘Paradero del niño’, for instance, is a Venezuelan tradition where musicians, playing violins, mandolin and drums, walk along with the townsfolk in representation of the first steps of the child Christ, celebrated on the days after Christmas (Suniaga Reference Suniaga, Lengwinat and Suniaga2013, pp. 160–3). The Violines Caucanos tradition from Colombia is another remarkable example. As is the case in Panama, these musicians perform on various platforms, becoming themselves participants in an active cultural dialogue and continuous musical development.

Figure 5. Violinist Efraín González performing with drummers in a tuna at the Festival de las Mil Polleras, 2020, Las Tablas. Photograph: ACODECO.

The introduction of the waltz, the mazurka, and the polka to Panama in the 19th century, and the subsequent development of the pasillo, were indeed quite influential in the formation of the 20th-century musical landscape on the Isthmus. Socially, the dances provided a platform concomitant with the social mobility throughout this eventful era in Panama. Musically, their popularity contributed structurally, harmonically and rhythmically to the forging of a unique dance music language. The triple/compound rhythms from dances like the pasillo became associated with the tambor corrido (see above). Duple dances, like those part of the contradanza, and later the danzón, mingled with the traditional tambor norte and the cumbia (see Example 3).

Example 3. Panamanian drumming airs in binary time. Transcription by the author.

It is clear from both the historical record and the musical evidence that the sectional form of the pasillo and its own European tributaries had a defining influence in the structure and harmonies of what is now universally acknowledged as traditional Azuerense music. When the Cuban danzón became popular in Panama, its similarly sectional structure (Manuel Reference Manuel2009) fit nicely into a cultural interchange already begun in Panama's dance floors, thus becoming a part of the discontinuous cultural dialogue which evolved into the danzón–cumbia, and then into típico. While the contribution of the Cuban danzón to Panamanian music is significant, a phenomenon discussed by Melissa González (Reference González2015) and to a larger degree by Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2021), the earlier popularity of the pasillo had a profound influence on Panamanian dance customs – musically and socially – and certainly merits our attention. I contend that the aforementioned structural, harmonic and rhythmic traits introduced by the pasillo and its European counterparts to Panamanian dance music became the soil in which danzón could flourish and itself evolve into a locally forged dance form and music. Furthermore, the danzón developed in Panama in parallel with Cuba and Mexico, not merely following them, as I discuss below. In the following sections, I explore how these diverse sources became the tributaries of the danzón–cumbia which, in turn, resulted through performance practice in the advent of modern cumbia popular, or música típica. I do this in tandem with a glance at the notion of legend and myth associated with the origins of típico and which so profoundly influence the ‘making’ of the tradition.

A thriving Panamanian danzón tradition

Origin stories for the danzón–cumbia and tales of how the Caribbean danzón found its way to Azuero dance between legend and reality, a phenomenon that becomes quite relevant when approaching the forging or ‘making’ of traditions in Azuerense music through scholarship. According to musician Simón Saavedra, for example, in recalling music lessons by his elders, a group of Puerto Ricans arrived in Los Santos province in the mid 1920s. They settled in the town of Pocrí, 10 kilometres from Purio, the home of Francisco ‘Chico Purio’ Ramírez. The visitors had brought a phonograph and listened to Caribbean music in their hours of leisure to remind them of home. It was not long before townsfolk pointed them toward Ramírez: ‘A man in the next town will play all of that music for you if you pay him’ (Saavedra 2021, personal communication). According to the legend, Ramírez was called in to Pocrí and pretty soon he became a fixture at the foreigners’ parties. ‘He played their music’, Saavedra adds, ‘but lots of it was very similar to the songs he later wrote’. We cannot know for sure which music the expats asked Chico to play, or how he played them, only that the legend seemed important enough to be passed on by music teachers – including Chico himself – to their students, as part of teaching the tradition of performing itself. A large-scale geographical survey was conducted by the United States across Panama from 1916. The 11th Engineers were indeed in the Azuero region in the mid 1920s, and remained there for a number of years, producing maps and detailed records of the terrain and demographics. The survey had the purpose of creating accurate cartography as well as supplying information ahead of the deployment of a defence strategy for the Panama Canal, then under U.S. administration (Young Reference Young1925, Wilson Reference Wilson1935). Further inquiry into this survey could potentially support the legend of Chico and the Puerto Ricans, but there is certainly evidence of a large and active US presence in the area in the 1920s.

Myth aside, the Cuban danzón was deeply rooted in Panama soon after it became a distinct genre in Cuba. Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2021, p. 29), citing Jaime Ingram (Reference Ingram2002), points toward a pre-1900 introduction of the danzón into urban centres in Panama, possibly through ‘several Cuban musicians’ who were active as bandleaders. We indeed know of waltzes, marches, polkas, pasodobles and pasillos (though not danzones) written by Cuban émigré Lino Boza, who arrived in Panama in 1880. His nephew, Máximo Arrates Boza, arrived with him at a young age and was active as composer after 1900. Arrates, as discussed below, did leave danzones as well as other dances, concert pieces and marches (Ingram Reference Ingram and Castillero Calvo2019, p. 464). Certainly, Arrates played an integral role in the growth of the danzón, but his output is post-1900. Cuban influence in Panamanian dance circles, however, probably started before the arrival of the Boza family, and was quickly absorbed by bands such as Iturrado's and Dubarry's. A noteworthy instance of contact with Cuban dance music took place during an 1877 visit by famed Cuban virtuoso violinist José White (1836–1918). His performances probably caused an impact on Panamanian violinists, composers and bandleaders, considering the small population of greater Panama City at the time.Footnote 10 White composed concert music as well as a number of dance pieces which are still widely performed today, such as La Bella Cubana. He played several shows at the Club Panamá with piano accompaniment (Ingram Reference Ingram and Castillero Calvo2019, p. 458).

The danzón culture continued to flourish in Panama, as revealed by archival sources, scores, written accounts and pre-1930 recordings. Documents from the period, although scarce and scattered in various archives, do provide some valuable information. An 1890 proposal to the Municipal Council of Panama City mentions that danzón public dances were, at the time of its drafting, the only such events that had been taxed by the city ‘at the rate of twenty-five pesos for an entire night’ as opposed to tamboritos, private dances, mejoranas, and serenades, for which the petitioner suggests rates between 50 cents and 2 pesos per event (Arberola, Reference Arberola1890). This is a clear indication that, already before 1900, the danzón was firmly entrenched in Panamanian urban consciousness. By the early 1900s, many of the most popular songs in Panama City were danzones, including La reina roja (1919) by Máximo Arrates Boza (Brunswick 41065-A).

So popular was the danzón in Panama already by the 1900s that pieces by Panamanian composers were being exported from the earliest days of commercial recording and performed by famous orchestras of the day, including Ángel María Camacho y Cano's orchestra, the Brunswick house orchestra (Orquesta Brunswick Antillana, often led by Camacho y Cano himself), and González Levy's Los Reyes de La Plena. ‘Tóqueme el trigémino doctor,’ a humorous danzón by prolific Panamanian composer Ricardo Fábrega (1905–1973) was recorded by Camacho y Cano (Brunswick 40933), González Levy (Brunswick 40911), and the Orquesta Típica Panameña (Columbia 3708), among others.Footnote 11 It was one of the first pieces to be broadcast in the Colombian Caribbean coast (Wade Reference Wade2002, p. 103). ‘El duque del Happyland’ (Brunswick 41065-B), a popular danzón by Panamanian Raymond Rivera (dedicated to the homonymous nightclub where danzón orchestras performed near the Panama City railway station) was another of the several Panamanian danzones recorded by Camacho y Cano with the Brunswick house orchestra up until 1930, including at least four others by Rivera.

This evidence reveals that Panamanian musicians did actively participate in a cultural dialogue with those from the circum-Caribbean region during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in a process akin to what Hettie Malcomson describes as ‘multiple origins’ at various stages of the prehistory of the danzón (Malcomson Reference Malcomson2011), and which can be read through the lenses of a permanent discontinuous cultural dialogue (Matory Reference Matory, Appiah and Gates2005). French- and English-speaking immigrants from the Antilles brought their music with them during the construction of the railroad. The French, and then the US canal efforts provided further opportunities for migrant workers who travelled in large numbers, many of them settling in Panama after work was complete. By the time Antillean immigrants arrived for these events, they already had rich salon dancing traditions of their own (Guilbault Reference Guilbault1985; de Jong Reference de Jong2003; Gansemans Reference Gansemans and Kuss2007). After a period of heightened musical activity in the transit zone since the Gold Rush (Castillero Calvo Reference Castillero Calvo2010, p. 312; Johnson Reference Johnson1848, p. 76; White Reference White1868, p. 88), local Panamanian musicians were able to have influential careers playing international genres for diverse audiences in Panama. Some became instrumental in bringing Caribbean styles to Panamanian dance halls and schools. Trumpeter and bandleader Simón Urbina from Colón (1889–1974), for example, performed in dance and theatre orchestras in Guadeloupe, New York, Barranquilla and Europe. He received a degree in Composition and Harmony at the International Conservatory of Havana before settling back in Panama in the 1920s where he became an avid music educator (Wade Reference Wade2002, p. 104; ISMU 2020).

Broadcasting was an important enhancement of the cultural dialogue between Caribbean music and Panamanian musicians. The first Panamanian experiences with the airwaves happened not long after the Panama Canal was completed in 1914. Marvin Alisky reports that the United Fruit Company began broadcasting as early as 1922 in Central America and the Caribbean (Alisky Reference Alisky1954, p. 516; IUAR 1923, p. 290). Some stations were powerful enough that emissions from Havana and San Juan would be heard in México (Alisky Reference Alisky1954, p. 515). One of such broadcasts from Havana was ‘heard over the radio in Panama’ in a 1923 programme which featured Panamanian singer María Teresa Vallarino and her sister Hilda María Vallarino, foreshadowing a series of live concert broadcasts that would begin later that same year from the radio transmitter installed at the US Submarine Base of Coco Solo on the Panamanian Caribbean coast, ‘which may be heard by radio enthusiasts in the Republic of Panama’ (IUAR 1923:290). The radio became a portal through which musicians were instantly communicated with music from the circum-Caribbean region and were deeply influenced by what they heard (Saavedra 2021, personal communication; Ramírez 2021, personal communication).

Considering the evidence at hand, and acknowledging that surely much remains to be uncovered, Cuban danzón arrived first in Panama most likely by way of water, informally, and became widely popular rather quickly through live performances in dances and cabarets, broadcast performances and notated music. Traits in the music were adopted and incorporated into practices already entrenched, as discussed in the previous section of this article. The danzón, I suggest, had become a part of Panama's musical landscape – and, one could argue, of Panamanian identity (Robles Reference Robles2022) – long before the first foreign commercial recordings became well known and during a time when much political and social change was in process. The popularity of the danzón, as shown above and evidenced by sound recordings, archival records, scores, oral tradition and writings such as Narciso Garay's (Reference Garay1930, pp. 28, 194, 201), was already widespread by the 1920s in Panama City and the rest of the Isthmus. It should not be surprising that ‘Chico’ Ramírez's compositions and those of his contemporaries, which I call the Azuero School (La escuela de Azuero), feature a number of distinct style markers from the Cuban danzón. In the following sections, I will expand on Sean Bellaviti's observations (Bellaviti Reference Bellaviti2015, Reference Bellaviti2021), particularly those dealing with rhythm and performance practice. I propose that these style markers are evidence of a process of influence and re-influence of danzón in Azuero, as part of a discontinuous cultural dialogue. I will, through this prism, examine the above-mentioned piece by Ramírez, ‘Los sentimientos del alma’, which is representative of an ample corpus of compositions by the Azuero School. This repertoire is widely acknowledged by scholars as the basis for the development of típico (Pitre Vásquez 2008; González Reference González2015; Bellaviti Reference Bellaviti2020a, Reference Bellaviti2021).

The Azuero School and the danzón–cumbia

The Cuban danzón, as well as other hybrid dance genres from the Caribbean, made it to the Isthmus at a time when Panamanians were experiencing the effects of a century of diverse and copious immigration while also struggling to find cohesive elements which could define a ‘Panamanian’ identity. As the danzón arrived in several waves and forms, it continuously found in Panama several bedrocks on which it could be adopted by performers, influenced by local traditions and reinterpreted by composers. It fit into musical practices already established such as sectional structures, harmonic-melodic design and polyrhythmic percussion platforms, as seen above. It also became an integral part of social interaction in light of mobility of both status and place. Cuban music influenced aforenamed Panamanian composer Ricardo Fábrega, who mixed local rhythms with formal and harmonic elements from both the danzón and the son, producing a type of tamborito-infused song style called tamborera, reaching international acclaim through performers such as Sylvia DeGrasse (González Reference González2015, p. 297), which then itself influenced Caribbean artists such as Cuban Dámaso Pérez Prado and Puerto Rican Bobby Capó, who recorded Fábrega's music.

In Chico Purio's Azuero, the danzón reached a musical culture characterised, as we have seen, by salon dancing, spontaneous tamborito performances, popular outdoor dances and colourful religious celebrations – all using the same musicians. While Simón Saavedra adamantly declares that he prefers pasillos, he acknowledges that it was the cumbia where danzón hit the hardest, and then became much more popular in all social circles, a fact that is echoed by Evelio Ramírez, the son of Chico and a dance violinist himself (Saavedra 2021, personal communication; Ramírez 2021, personal communication). The new Cuban dance form par excellence became a protagonist within the discontinuous cultural dialogue (Matory Reference Matory, Appiah and Gates2005) in the heartland of central Panama.

We have seen how non-choreographed couple dances like the waltz and the pasillo were popular in Azuero during this time. We have also explored how the music performed at elite functions in Azuero was also played at popular dances, and further how the tamborito and the cumbia were also enjoyed in oligarchic circles. It was quite natural that the danzón–cumbia came to be adopted into the couple dance repertoire of both elite and popular dances. Composers of the Azuero School, violinists most of them, performed in all contexts accompanied by guitars, mejoranas (a five-string Panamanian chordophone of the lute family)Footnote 12 and drums: private homes, outdoor celebrations and religious ceremonies. Chico's fame grew up to the point of legend. Evelio ‘Vellín’ Ramírez (see Figure 6) recalls his father's stories of the first dances where he performed in Purio. According to ‘Vellín’, Chico began playing professionally at age 17, at a time when a small town such as Purio would hold four simultaneous dances in private houses for public feast days where danzones, cumbias, pasillos and foxtrot, among others, would be performed. This practice served the dual purpose of dividing the townsfolk into several venues (there were no public venues large enough for all to gather), and also for the practical reason that the single violin-led ensemble would not be heard for too numerous an audience. This meant that at least four violinists performed simultaneously on a single night in separate venues. As Chico's popularity grew, ‘Vellín’ recounts, couples lined up outside the house where he was performing for a chance to dance even once to his music. ‘The older violinists had him play at far-away houses so that people would stay in the centre of town, but they still went to him, no matter how far his venue was’ (Ramírez 2021, personal communication). Even though Chico lived in a small coastal town near the southern tip of Azuero, he was indeed connected through phonograph to a wide array of musical influences, ‘even classical’, reports Evelio, ‘he always talked about Beethoven and Paganini’ (Ramírez 2021, personal communication). Nowadays, there is a bust of Francisco ‘Chico’ Ramírez in the main square of Purio, and he is called the ‘Father of the Danzón-Cumbia’ (Carrasco Reference Carrasco2015). His popularity began modestly, by playing in small affairs as described by his son, and arguably became quite large when his music began to be recorded by accordion conjuntos from the 1940s onward – more on this in the following sections of this article. Perhaps Chico's best-loved composition, and one of the first to be notated, is the aforementioned ‘Los sentimientos del alma,’ written in 1928 and presented in Example 4.Footnote 13

Figure 6. Violinist Evelio ‘Vellín’ Ramírez, son of Francisco ‘Chico Purio’ Ramírez, 2021, Purio. Photograph by the author.

Example 4. ‘Los sentimientos del alma’, as commonly performed.

Many of the traits found in ‘Sentimientos’ and discussed by Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2021) and below can be heard consistently in subsequent danzón–cumbia repertoire by Chico and his contemporaries of the Azuero School, among them Clímaco Batista (1907–1978), Manuel José Plicet's son, Tobías (1906–2004), Escolástico Cortez (1904–1976) José Antonio Sáez (1904–1956), Abraham Vergara (1905–1981) and José De La Rosa Cedeño (1903–1998). Ramírez uses two-bar rhythmic blocks for the melody of the first section, composed of closed phrases, where a cinquillo-based measure is followed by one without syncopation. Peter Manuel (Reference Manuel2009, p. 197) shows how this alternated cinquillo pattern appears first in Cuban creolised contradanzas and then becomes a fixture of the danzón (one can hear it, for example, in the baqueteo pattern of the timbal, see Example 6A below). The alternated cinquillo pattern can also be heard in the traditional caja santeña accompaniment pattern for danzones–cumbia (see Example 5 below). Furthermore, the cinquillo appears consistently in cadential figures in ‘Los sentimientos’ and frequently in Azuero School notated compositions.Footnote 14 The contrasting section in the parallel major is yet another link to the Cuban danzón and, as discussed above, the pasillo-waltz complex earlier. While danzones–cumbia do not necessarily modulate in the contrasting section (see table in Bellaviti Reference Bellaviti2021, p. 34), the character of the music becomes livelier and phrases become shorter and end on the dominant, a trait described by Garay (Reference Garay1930, p. 198). In the case here presented, phrases first shorten to four repeated bars and then a two-bar refrain vamp. This allows for indefinite repetition of these phrases, as indeed they are performed today in popular dances and folkloric representations. Manuel (Reference Manuel2009, pp. 198–9) brings attention to this trait in the Cuban contradanza repertoire which precedes the danzón and the son, a trait the author interprets as a potential contributing factor to the later development of the montuno. Footnote 15 These open-ended sections are discussed by Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2021, p. 33), which he calls the ‘open-ended half’ or the cumbia portion of a danzón–cumbia. In the same way that the open-ended, ‘restless’ shorter phrases lent themselves for indefinite repetition in dance performance in the predecessors of the danzón, these shorter phrases often serve modern típico performers as improvisational passages to engage in call-and-response or instrumental soloing, much in the same ways as they do in Cuban son and even in modern salsa.

Chico Purio's ‘Sentimientos’ is a representative example from a substantial repertoire of danzones–cumbia composed by a generation of musicians, violinists most of them. Their birth coincided with the decline of the formal dance era, the construction of the Canal, the separation from Colombia, the consolidation of the Cuban danzón and its quick transplant into Panamanian consciousness, and the advent of radio. It is now universally acknowledged that the vast repertoire of danzón-infused cumbia written by the composers of the Azuero School is the platform for the development of the modern música típica. This unique period was the stage for the forging of an early ‘Panamanian’ identity, affected by political change, a quest for sovereignty linked to the United States’ takeover of the Canal enterprise, and the cultural diversity of a people struggling to recognise themselves as a unified nation. A final step in the process of influence and re-influence would be taken later, when the generation following the Azuero School supplanted the violin in favour of the accordion, a phenomenon that has been approached by Panamanian folklorists such as Eráclides Amaya (Reference Amaya1997) and José Antonio Vargas (Reference Vargas2003), and further discussed by Melissa González (Reference González2015) and Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2020a, Reference Bellaviti2020b, Reference Bellaviti2021).

However problematic the reception of innovations was, performers enthusiastically sought to adopt the ever-increasing influences that arrived to Azuero from the 1940s. A wider array of local radio stations and commercial recordings certainly contributed. More importantly, musicians travelled between Panama City and the countryside, becoming active participants in the cultural dialogue which developed into Panamanian típico. The brothers Julián and Antonio Gáez, for example, transported Azuerense music to the capital, as well as foreign styles to the peninsula. Antonio was a member of the National Symphony, but also played formal balls and traditional music (Garay Reference Garay1930; Charpentier Reference Charpentier1975; Gáez, D. 2021, 5 October, personal communication (Las Tablas, Panamá)). Tobías Plicet from La Villa de Los Santos became a respected bandleader and arranger apart from being himself a composer of hundreds of dance pieces. He worked for various radio and television companies, recorded extensively with his conjunto, performed for dance troupes and formal balls, and was hugely influential in the efforts for keeping the violin a part of Panamanian musical traditions in spite of the accordion's commercial conquest of Panamanian popular dance music. These representative examples reveal that, while the music scene in Panama kept continuously evolving and aware of foreign styles, it also made sure the perceived roots of traditional music remained relevant. Frequently, both sides were practised by a same individual, as is the case with Plicet, but the history of this evolution is still today the subject of critique by folklorists who perceive that changes bring about oblivion. I will address this issue in the context of my discussion on the inclusion of the accordion in the cultural dialogue of típico in the following section.

‘Gelo’ Córdoba: myth, legend, and ‘Panamanian’ musical identity

Much has been written concerning the introduction of the diatonic accordion to Panama and to its cumbia, where it ‘replaced’ the violin (Zárate Reference Zárate1962; Brenes Reference Brenes1963/1999; Amaya Reference Amaya1997; Vargas Reference Vargas2003; Pinzón Reference Pinzón2018). The diatonic accordion found solid ground in other ports of the transatlantic circuit, replacing the violin and other traditionally performed instruments. This is the case of the Colombian Caribbean coast (Gilard Reference Gilard1987a, Reference Gilardb; Wade 2000), Cape Verde (Hurley Reference Hurley1997) and the Dominican Republic (Hutchinson Reference Hutchinson2011), to name just a few. Although research on this topic is far from exhausted, it is plausible that the accordion arrived in Panama late in the mid 1800s, as it was quite popular among sailors of the time. Panamanian ethnomusicologist Gonzalo Brenes mentioned records which show the accordion accompanying cumbias and atravesaos on the Isthmus as early as the Thousand Days’ War (1899–1902), although he did not provide citations. The author further declared that ‘musicians from those times affirm that the accordion was used back then in town dances’ (Brenes, Reference Brenes1963/1999, p. 331). It was likelier, however, that the few accordions that did make it to Panama in the 19th century were sparse, disseminated through various areas, and used to accompany salon dances and religious music in discreet contexts. Egberto Bermúdez (Reference Bermúdez1996) and Peter Wade (Reference Wade2002) argue this point compellingly in reference to the Caribbean coast of Colombia. The accordion, in any case, did not become a sustained trend in Panamanian cumbia, with wide commercial support, until the 1940s.

Several theories will arise when local folklorists and musicians are asked who brought the first accordion to the cumbia, or how it was first used, or in which contexts. The matter can become heated, but there is little argument that the accordion is today a strong marker of Azuerense identity. It is only in the 1940s, as mentioned above, that we begin to see an actual ‘accordion trend’ emerge in Panama. This is when the first commercial recordings are made and when we have the first generation of musicians devoted exclusively and professionally to accordion performance, spearheaded by Rogelio Córdoba. The topic of elite vs. popular dances in Azuero and how the accordion made its way from the decks of ships to Los Santos will provide matter for study in coming years as documents continue to surface from personal and institutional archives. In the meantime, and for the purposes of this article, it suffices to say that the accordion made its way to iconic status in Panama from the sea, then upward from the grassroots. Along the way, accordion cumbia playing in Azuero became common ground for experimentation, where musical traits coexisted and influenced one another.

Rogelio ‘Gelo’ Córdoba (1911–1958) fully embodies the Panamanian accordion myth, in a manner similar to the way Francisco ‘Pacho’ Rada does in Colombia. The story of how and why he came to play music, how he learned the violin and how he later decided to switch to the diatonic accordion is surely the topic of legend in Azuero. As is the case with ‘Chico’ Purio and his generation, legend and myth help to fuel at one time the preservation of perceived tradition as much as it does the impetus for evolution of said tradition. This tension is characteristic in the development of a culture of innovation in Azuerense music. Like many of the first professional accordionists, Gelo was originally a violinist, who catered to both crème (as Celia Moreno de Arosemena calls the balls of the Azuero elite) and popular dances. He is largely believed to be the first to switch to playing dance music on the diatonic accordion – he was certainly the first to make commercial recordings, for Grabaciones Eléctricas Chacón (GRECHA). Melissa González provides biographical information on ‘Gelo’, and the reader will find there an ample description of his instrumental role in the transition, and of the influence he exerted as the leader of his conjunto, ‘Los Plumas Negras’ (2015, p. 109ff). Gelo, González tells us, started playing the violin for religious occasions, and soon found a home in the dance circuit of Azuero, which is consistent with the trans-platform trend I discussed in previous sections. Gelo's incursions in public dances coincided with his decision to switch to the accordion. It is not surprising that the repertoire of his first recordings as accordionist included well-known danzón–cumbia compositions by Azuero School composers such as Escolástico Cortez's ‘Arroz con mango’ (Rice with mango). Some pieces were modified in order to accommodate for the lack of chromaticism of the diatonic accordion, a practice observed by Sean Bellaviti (Reference Bellaviti2021).Footnote 16 Even though Gelo's version of ‘Arroz con mango’ lacks some of the violin's idiosyncrasies, the music retains many of the elements I have discussed above concerning ‘Los sentimientos del alma’, such as closed phrases in the verse sections, the use of the alternated cinquillo pattern, and the shortening of phrases in the final section.

Performers like ‘Gelo’ who first brought the danzón–cumbia into popular accordion dances were at first frowned upon. ‘Classical’ danzón–cumbia was increasingly seen by folkloristas as a ‘pure’ Panamanian music, whereas the accordion conjuntos which appropriated many of its style markers were disdained by traditionalists (see Zárate, Reference Zárate1962). The music of the acordeonistas (accordion players) nonetheless endured thanks to the acceptance of audiences. The commercialisation that followed the first recordings helped to make accordion conjuntos widely popular throughout Panama, not only in Azuero. Former violinists who used to play at small dance venues began exploring the repertoire they already knew on the accordion in larger halls and many went on to have successful careers as professional acordeonistas. Industrially built accordions were sturdier and cheaper than imported hand-made violins; they were louder, and did not require the constant tuning and care violins did. Accordions were also picked up by microphones more easily than the violin, even if conservative observers like Manuel F. Zárate (Reference Zárate1962, p. 150) considered heavy amplification ‘of very bad taste’ and incompatible with what he believed to be the elegant essence of the cumbia. As radio made it easier for musicians to learn from circum-Caribbean urban styles, the accordion cumbias flourished and became gradually more accepted toward the second half of the 20th century.

The generation following ‘Gelo’ Córdoba is responsible for setting the main trends in Panamanian cumbia. Lyrics were introduced and típico became a genre of songs, as opposed to only dance pieces – even older pieces such as ‘Los sentimientos’ were given lyrics when recorded by modern conjuntos.Footnote 17 Roberto ‘Papi’ Brandao (1940–2017) was the first to play dances while standing up, thus creating the figure of a ‘frontman’ for conjuntos and consolidating the accordionist's role as bandleader. Another violinist-turned-accordionist, Ceferino Nieto (1937–), introduced the electric bass to his conjunto. Dagoberto ‘Yin’ Carrizo (1939–) and Tereso ‘Teresín’ Jaén (1942–2004) pioneered the use of simpler song forms, foreign urban rhythms, and the mixing of típico percussion patterns. This is addressed in the following section. Competition and success furthered the culture of innovation, where even the most ‘traditional’ accordionists, such as Alfredo ‘Fello’ Escudero (1946–), are enticed to introduce changes routinely in order to remain relevant. It is during this generation that the music performed by the now established accordion conjuntos began to be called música típica (see González Reference González2015). When the electric guitar and bass were introduced in the 1960s, players adopted patterns from both the traditional mejorana and guitar accompaniments they used for pasillos, contradanzas and cumbias as much as they borrowed figures from Cuban son. The resulting bordoneo guitar pattern was juxtaposed with syncopated versions of tresillo and cinquillo patterns in the electric bass, with liberal use of ghost notes and parallel fourths as ornaments. The use of syncopation and anticipation fit well with a percussion section that, as explored below, kept the march forward through de-emphasis of the downbeat and interplay of high and low accents on the off-beats, a relevant rhythmic device which has not been covered by the existing literature, and which serves as a link to the Caribbean multiple origins of típico.

The 1940s and the 1950s were the critical time when the burgeoning típico became a distinct genre, separate from the ‘classical’ Panamanian danzón–cumbia. At the same time, this new urban cumbia performed by the first generation of accordion típico bands absorbed performance practices from modern Cuban and Mexican danzón and son orchestras, just as the previous generation had adopted melodic-harmonic traits from the danzones they heard through live performance, contact with musicians and the radio. Sean Bellaviti states that one of the major innovations of típico performers, the inclusion of the timbales, occurred ‘as early as the 1930s’ and he credits violin conjuntos for it, ‘clearly modelled after the percussion section of (…) [La] Sonora Matancera’ (Bellaviti Reference Bellaviti2021:31). This claim seems problematic when confronted with iconographic, archival and ethnographic evidence. Even after accordions took over the dance music scene in the late 1940s, conical drums and caja santeña continued to be used regularly, as shown by photographs and recordings. According to Evelio Ramírez, many early violin performers including his father preferred to play even without drums, only accompanied by guitar and maracas (Ramírez 2021, personal communication). Furthermore, there are no commercial or field recordings to indicate that violinists in Azuero performed with timbalitos in the thirties. The historical evidence leans toward a more organic introduction of the timbales to Panama when danzones became popular, as stated in the previous section of this article.

Compellingly, as mentioned above, we do have previous orchestral danzón recordings both from Panamanian performers or by Panamanian composers, which do use full percussion, including timbales. These recordings are from the same period as the very few early cuts of La Sonora back when it was called the Estudiantina Sonora Matancera (Victor 46225, 46447). Timbalitos do not show prominently in these son recordings, favouring bongos instead. La Sonora became popular abroad only after 1945 when Bienvenido Granda and Daniel Santos began recording with the ensemble, and by that time, timbales had long been introduced to Panama, at least in urban centres. Conversely, Panamanian recordings and composers (who already featured timbales) were so popular that they even influenced notable international artists. Dámaso Pérez Prado, who was the original pianist for the Sonora, would later record Fábrega's ‘Guararé’ in 1962, as leader of his world-famous mambo ensemble (RCA Victor 45N-1323B).

Aside from actual live performances, Panamanian danzones, tamboreras and son recordings would have been far more accessible than early Sonora recordings both in the large terminal cities and in Azuero. There are indeed a number of originals in local private collections today. The record points toward a more complex and discontinuous process of dialogue in Panama, which occurred in tandem with the development of, for example, son in Cuba, not only through the following of a single artist. Timbales, as I discuss in the section below, became a trend in conjuntos after the inclusion of the accordion. Pretty soon, the interaction between accordion and timbales became the heartbeat of típico. Understanding this history of Caribbean influence, adoption and adaptation is important when considering the multiple origins of típico and the subsequent evolution through its modern history.

The timbal: at the heart of típico

Most contemporary típico musicians, such as Joaquín Chávez mentioned above, acknowledge that the pairing of the accordion and the timbal is central to the identity of the genre. ‘The timbal is the heart of típico’, declares Chávez (Reference Chávez2017), in contrast with Manuel F. Zárate's unflattering observations about this instrument and its role almost 60 years prior (1962, p. 61). The timbal was adopted into the danzón–cumbia from the late 1940s from local (Panamanian) pan-Caribbean music orchestras as the accordion was becoming a sustained trend in Panamanian cumbia performance, as shown by commercial recordings, iconography and testimony from its original practitioners (Patiño, A. 2021, 18 August, personal communication, Santiago, Veraguas). Timbales replaced the caja santeña as timekeeper of the ‘traditional’ ensemble, retaining some of the rim techniques used in the aires de tambor, where danzón style markers can still be heard today – cajeros will perform a paused, cinquillo-infused two-bar pattern for the verse section of a danzón cumbia, and a one-bar pattern for the refrain section, which later evolves into the rumba, as discussed below (see Example 5).

Example 5. Rhythms used on the traditional caja santeña when accompanying danzón–cumbia, in the canto or verso section (A) and in the rumba section (B). X shaped noteheads are played on the rim. Transcription by the author.

The peculiar timbre of the timbales quickly became one of típico's most distinctive markers. At first, makeshift timbales were cut from gas, paint or milk cylinders in imitation of industrially manufactured ones used by famous Panamanian orchestras called the Combos Nacionales, whose performances were immensely influential in Azuero and on its musicians. This is well remembered by Alberto ‘Fulo’ Patiño, the original timbalero for Alberto ‘Pepo’ Barría's conjunto. When called by Pepo in the 1960s to play with him, Fulo Patiño built his timbales out of paint cans, since instruments were not readily available. ‘With those can timbales we toured all around the province, even going by boat from Montijo to Arena de Quebro [in western Azuero]’, recalls the musician (Patiño 2021, personal communication). Even in the 1950s, some conjuntos still recorded with traditional conical drums and cajas. Timbales truly became a trend in Panamanian music alongside the inclusion of the accordion, a trend that Manuel Zárate characterised as alarming: ‘the rhythms played formerly by drums, now come from boxes and cans’, suggesting that in the early 1960s, this was still very much an ongoing transition (Zárate Reference Zárate1962, p. 61). Gradually, however, factory-built timbales, congas, and tumbadoras supplanted all Panamanian percussion in conjuntos; the churuca remained a binding element to tradition.

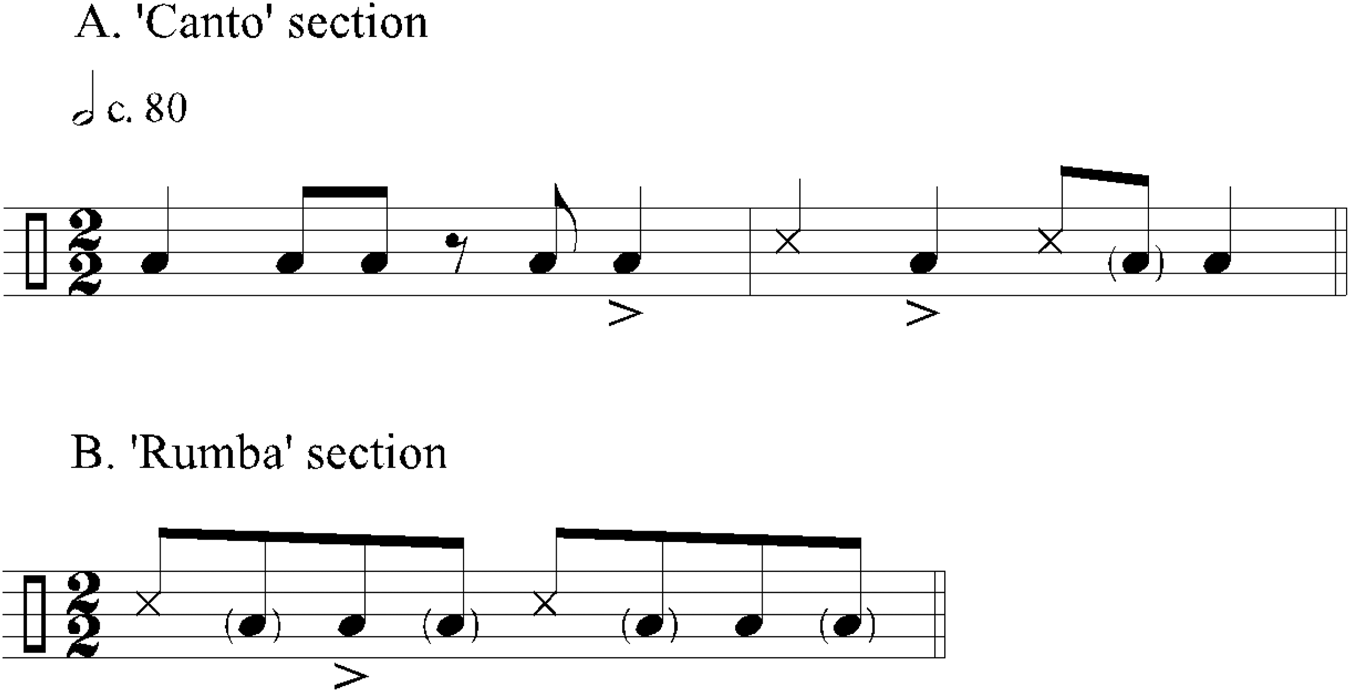

Joaquín Chávez, aside from being first call for típico recording sessions, is also a much sought after teacher and social media personality. Like most modern players, he identifies two main sections in típico songs: canto and rumba. The canto or verso section, which is when the song verses are delivered, can be supported by either baqueteo or pasebol rhythms. The rumba section, somewhat equivalent to the soneo of a salsa song, has its own rhythmic base. When discussing and teaching the baqueteo, Chávez touches on its function as the ‘key’ that holds the band together and also on the history of the rhythm as the ‘grandchild’ of the danzón and the cumbia. ‘You need to be aware of both function and history before you try to change things’, he explains young musicians when addressing his innovative playing with the Sandovals, ‘it is not enough to just learn the pattern’ (Chávez Reference Chávez2017). The reader may be familiar with the term baqueteo as referring to the isorhythm of the first section of a danzón, associated with the timbal. The term comes from the use of baquetas (drumsticks) instead of bare hands. The wide array of timbres possible through varying strokes and muffling techniques makes baqueteo a rich and easily recognisable pattern that cuts through the ensemble. While Cuban orchestras such as La Sonora Matancera were influential in Panama as mentioned by Sean Bellaviti, particularly addressing his conversation with Daniel Dorindo Cárdenas (2020a, p. 106), the popular dance music scene in Panama from the late 1800s made it possible for Caribbean trends, including the timbalitos, to enter organically through several channels, as I have discussed above. By the 1940s and 1950s, several Panamanian combos were busily recording and performing live dance shows featuring music with influences ranging from son and calypso to blues and soul (Buckley Reference Buckley2004). It is likelier that the change of percussion and string instruments used in accordion conjuntos starting in this critical stage of development is the result of a complex web of influences, mostly through local bands and their performers, rather than only from a single source. It should be noted that the baqueteo and rumba terminology is a relatively late addition to the típico vocabulary. Original timbal performers such as ‘Fulo’ Patiño, although they certainly played the rhythms, did not call them as they are now universally known by practitioners (Patiño 2021, personal communication) (Example 6).

Example 6. Baqueteo patterns in Cuban danzón and Panamanian típico. The ° symbolises an open stroke. The X noteheads are played on the rim of the drum. Transcription by the author.

The Baqueteo

The baqueteo rhythm of the típico is outlined by the timbales. As in the danzón, it is simple, but nuanced. My transcriptions of both danzón and típico baqueteos are presented in Example 6. Although both techniques imply muting one of the drumheads, they are performed differently. As shown below, the baqueteo in típico is performed in a peculiar manner, requiring the use of a shorter stick, which performers switch to a standard-sized when playing other sections. One of the most important aspects of the baqueteo in Panamanian típico is a conspicuous accent on the second crotchet which provides a backbeat that serves as a signal for performers on the first half of the measure. Sean Bellaviti mentions this practice in passing (2020a, p. 143), pointing earlier towards a ‘prominent downbeat feel’ in the pattern (Bellaviti Reference Bellaviti2020b, p. 182). I contend, however, that the actual lack of a strong downbeat in the baqueteo generated by the audible emphasis in the second beat is a key marker of the genre which separates it from other regional cumbias and also links it to its Cuban roots as I discuss in this section.

The second-beat accent is also marked by the other percussionists in the conjunto, complementing the pattern and creating a polyrhythmic matrix which ties melodic gestures together and liberates dance steps from following beats strictly. This accent is the one referenced by Chávez, cited in the introduction of this article. The fourth crotchet is also accented, but on the low (‘hembra’) drum. This beat fits into the fourth position syncopated anticipation of the bass line, following David Temperley's terminology (Reference Temperley2019, Reference Temperley2021). Figure 7 shows a basic timbal baqueteo setup in típico. Note that the smaller (‘macho’) drum is placed on the left, as opposed to the traditional danzón/son/salsa setup. Baqueteo technique in Panamanian típico calls for the use of a third stick which is cut so as to fit inside the 13 or 14-inch rim of the macho drum, as shown in Figure 7. This shorter stick (used for the baqueteo section exclusively) cut to fit by típico timbaleros, is kept against the drumhead with the left hand, while the right hand holds the full-sized stick with a conventional match grip. Left-hand strokes are consequently performed with the entire stick, rather than the tip. This allows for a distinct set of timbres unique to típico, which the player controls through pressure of the left hand, both between stick and head, and also between hand and stick. Timbaleros use both the left stick itself and the heel of the hand for various degrees of muffling, producing a richness of timbral possibilities for both left- and right-hand strokes. While clearly a descendant of head-muffling from other Caribbean styles, the technique involving a shorter stick in Panamanian típico is quite unique.Footnote 18 The pattern is played according to each conjunto's style, so that they are acknowledged by musicians and audiences as unique, yet still characteristic of the genre. I have offered examples of baqueteo variations from popular songs from three influential conjuntos (see Example 7).

Figure 7. Timbal setup for típico, with the macho drum to the left. Notice the unmatched sticks used for the típico baqueteo on the left panel. The short stick is meant to fit within the rim of the 14 inch macho drum to allow for the left-hand technique, shown on the right panel. Photographs by the author.

Example 7. Examples of baqueteo variations from three well-known conjuntos. Transcription by the author.

The Pasebol

Another pattern commonly used for the canto section is the pasebol, a term which comes from the contraction of paseo and bolero. Here, matching sticks are used, and there is no muffling, both hands are free. The timbral vocabulary and dynamic variety is less nuanced than the baqueteo's, but it does add rim shots as a norm (see Example 8). The pasebol retains the main qualities discussed above for the baqueteo, regardless of tempo: a high accent on the second crotchet (a rim shot in the case of the pasebol), and a low accent on the fourth. The accented backbeat of the percussion de-emphasises the downbeat as it occurs in the traditional aires: corrido, atravesao and norte.

This helps the flow of the music propel forward, aided by the dynamic role of the churuca. The flow is ‘circular’ as the high and low accents alternate, avoiding a sense of ‘arrival’ at the downbeat. In spite of the high energy of performance, syncopation, nuanced timbale strokes and the second and fourth position alternation of high/low off-beat accents keep the music's forward pace agile. The curious observer at a jardín dance might notice that the most seasoned típico dancers do not step on the downbeat – or on any particular beat. They dance very close to one another – or pegao (stuck together) as Panamanians would say – and move usually at a faster pace than the music does. Even though beats do not coincide with steps, the flowing nature of both movement and music is undeniable. The absence of a downbeat emphasis contributes to both the unbound dance step and the perception of flow. To illustrate this point, the reader may compare the baqueteo in típico to cumbia patterns in other regions of the Americas, such as Colombia, where stressed crotchets with the rhythm ! qn qn and heavy downbeats on the bass line ! h qq invite dancers to emphasise downbeat steps.

Example 8. Pasebol pattern. Transcription by the author.

The Rumba

The rumba occurs usually in the final section of a song. It is somewhat analogous to a soneo section in Cuban son in that a cowbell is introduced, phrases become shorter and vocals employ call and response. Both may have derived from the final section of the Cuban danzón's rondo structure – when danzones–cumbia are performed within a típico context, the final section of shorter open-ended phrases is almost invariably performed in rumba. Footnote 19 In the rumba section of típico, a refrain and new verses are usually sung by the main singer in alternation with accordion iterations of the same melody. Some songs also include accordion improvisations in the rumba section. The cowbell is played on each crotchet, but emphasis remains on the backbeats through orchestration (see Example 9). The pattern is also sometimes used for the intro, where music from the later rumba refrain is often foreshadowed. As discussed above and shown in Example 5, in traditional danzón–cumbia practice, the caja santeña will mark this pattern even without the use of a cowbell. The change from a two-bar to a single-bar pattern is a clear manifestation of the agency that the early introduction of danzón effected on local Panamanian musicians, whose roots were already firm in local consciousness by the late 1800s. Later adoption of the timbale set – which includes the cowbell – fits quite well in modern típico as it does with the Cuban son, since the structural elements from both genres stem from the form used by the danzones which grandfathered both. It was quite natural for the cowbell to be incorporated in the rumba as it appears similarly not only in the son, but also in the cha-cha, the mambo and contemporary salsa.

Example 9. Rumba pattern. Transcription by the author.

A culture of innovators

By nature of its origins, and those of its main tributaries, típico is a platform for innovation and change.Footnote 20 The markers which make a song acknowledged as a típico song are usually circumscribed to instrumentation, the percussion patterns seen above, and song structure. First, I will address matters of structure and rhythm. A standard típico song will begin with an intro (possibly in rumba), then verses will be sung in the canto section using either baqueteo or pasebol, followed by a final refrain and/or instrumental section in rumba. In a number of songs, particularly those following the cumbia-danzón model set by ‘Chico Purio’ Ramírez and the Azuero School, there will be a modulation to a related key (as in most earlier pasillos). This will often be the parallel, but can also occur from a minor key to the major key one step below. This is the case of ‘Penas’ (1982), composed by Luis Carlos Cleghorn and recorded by Ulpiano Vergara & Lucho De Sedas. In this song, the G minor canto section modulates down to F major and then back to G minor for a rumba section with accordion solo. This unlikely downward modulation responds to the layout of the diatonic button accordion, where both these keys are played on the same row. Danzones–cumbia such as those by Chico Purio use more frequently the relative or parallel for the contrasting section, as they were originally composed on the violin and influenced by European salon dance harmonies. It is not uncommon to hear contemporary típico composers talk about a new song they just finished as using ‘los acordes de Chico Purio’ (Chico Purio's chord changes), as accordionist-composer Nicolás Aceves Núñez once told me during our lessons. To one in the típico milieu this indicates that the song has an A baqueteo section followed by a B baqueteo section in a related key, and then a final open-ended rumba. Núñez could simply begin playing and the band would follow without much effort or rehearsal, as I usually witness musicians do.

Not all típico songs follow danzón–cumbia structure conventions, though. Many variants in form and combinations of rhythmic devices do occur, and have since the regular adoption of the accordion and the timbales. Típico is, undeniably, a culture of innovation, the fruit of a dynamic dialogue. In a culture such as típico's where change and cultural exchange are constant, many artists can fashion themselves ‘the first’ to introduce a particular aspect of performance, whether or not it evolves into a trend. An early innovator is the aforementioned Teresín Jaén. One strategy that Jaén used in order to distinguish himself from the norm was the use of the rumba pattern throughout an entire song, thus omitting the baqueteo. This is the case with ‘Amor con papelito’ (‘Love with papers’, c. 1970), in which the audience will hear the cowbell-led pattern for the duration of the song. There is no baqueteo rhythm, but there are verses, and there is consequently no switch to a more active, involved section at the end of the canto. The whole piece is a canto with high-energy rumba rhythm. Jaén was considered an eccentric during his time, but he was no stranger to the history and traditions of his art. He started out as a violinist, learning technique and repertoire from his grandfather. Yet, in spite of him being considered an outlier by traditionalists, his innovations made his music quite popular, enough to earn him the nicknames ‘El taquillero’ and ‘El Rey’ (‘The Box-Office hit’, ‘The King’). Dagoberto ‘Yin’ Carrizo, from the same generation as Teresín, is another prominent innovator of típico. His 1985 song ‘Los algodones’ (‘The cotton trees’) features a fusion of Dominican merengue with cumbia. To bring attention to the blend, the song opens with the percussion section playing the merengue-infused pattern by themselves, before Carrizo's accordion and rest of the conjunto joins in. Carrizo is unquestionably one of the most iconic performers in Panamanian típico, the first to enjoy international success and to have multiple platinum records as típico singer, accordionist and bandleader. Armed with knowledge and judicious use of the baqueteo, pasebol and rumba, early innovators as much as contemporary ones find significant ways to remain footed within the defining stylistic trends of típico. These are, of course, ever-changing themselves, as newer generations of musicians and audiences continue to reinterpret the music through performance and appreciation.

Not least important is the distinctive instrumentation used by típico conjuntos which crystallised through the 1950s and 1960s. This is seldom modified through innovation; the colours of the ensemble and the ways in which players interact with one another help listeners to acknowledge the music as típico. Once the ensemble became consolidated at the end of the 1960s – accordion, timbales, congas, churuca, electric bass, electric guitar, cantalante – it remained a recognisable, stable part of the típico identity. The accordion–timbal connection is the most determinant marker of the ensemble, considering that from this partnership flow the melodic gestures, the harmony and the isorhythmic structure which holds all the other elements and instruments together. A German instrument with Chinese ancestry paired with an afro-Cuban instrument which, in turn, replaced a Spanish drum of military provenance, came together in a music with complex, diverse roots from all across the transatlantic trade circuit.

‘El gusto’

When a conjunto performs with a natural, almost instinctive understanding of the baqueteo, the pasebol, and the rumba, and of the subtleties of the interaction between polyrhythm and melody, locals say they found ‘el gusto’, or ‘the groove’. As Joaquín Chávez points out, ‘you cannot play it if you cannot feel it’ (2017). The dancers can feel it and it propels them across the jardín floor. Musicians feel it and they are instantly connected to a musical tradition which, although recently consolidated, has older roots – and ‘routes’, to borrow from Malcomson's title (2011). Of course, Chávez is not referring to a sensorial tactile experience, but to the feelings attributed to the realm of the spiritual, like Chico Purio's ‘Sentimientos del alma’ that one cannot verbalise without taking shelter in metaphor and rhetoric, or in the eloquence of a textless melody.

Conclusions

Panamanian popular dance cumbia, or típico, and its main predecessor, the danzón–cumbia, are the dynamic result of mutually influential discontinuous dialogue (Matory Reference Matory, Appiah and Gates2005) between cultural–musical elements from all across the transatlantic trade network. These affluent elements themselves were subject to the same influence/re-influence processes, making the origins of típico diverse and rich, as evidenced by its rhythmic design, harmony, and structure. As diverse as its tributaries are the channels through which the contributing elements of típico made their way to Panama. Trade, religion and large construction projects all provided ample opportunities for cultural exchange and were rich platforms for cultural dialogue, long before popular Caribbean orchestras of the recording era. The Caribbean cumbia, salon dances both directly from Europe and in various stages of circum-Caribbean creolisation, Roman Catholic processional traditions, Panamanian tamborito and the Cuban danzón, among other contributing elements, coalesced on the Isthmus during a unique period of social change. So popular was the danzón in Panama that Panamanian composers such as Raymond Rivera and Ricardo Fábrega exported danzones from Panama which were recorded, performed and broadcast extensively abroad by acclaimed performers such as Dámaso Pérez Prado and Ángel María Camacho y Cano. This is clear evidence of a true cultural dialogue with agency by Panamanian musicians.