We work at a time of unprecedented change in postgraduate medical education and workforce planning in the UK (Reference Whelan, Jarrett and MeertenWhelan et al, 2007). The latest of these changes has been the introduction of the new format of the Royal College of Psychiatrists' membership (MRCPsych) examination (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/exams.aspx). The old structure of Part 1 and 2 examinations, each comprising both written and clinical components, has been replaced with three written papers (Parts 1–3), followed by a final clinical examination, the Clinical Assessment of Skills and Competencies (CASC). Thompson (Reference Thompson2009, this issue) discusses the context of the changes to the MRCPsych examination, as well as presenting a critical evaluation of the CASC. Our primary aim is to describe the organisation and evaluation of a mock CASC examination and course. Thompson's article considers why the College has introduced a new format; we focus on how trainers may devise a mock clinical examination for their trainees in light of these changes.

Background

As organisers of an MRCPsych course, we have been providing mock Observed Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) for trainees since the introduction of this format into the old Part 1 examination by the College in 2003 (Reference Pryde, Sachar and YoungPryde et al, 2005). These have been much valued by trainees but are both expensive to organise and labour intensive, requiring 12 examiners to ensure a full OSCE circuit. The largest expenditure is the standardised patients' (role-playing actors) fees. However, Naeem et al (Reference Naeem, Rutherford and Kenn2004) developed a framework for conducting an MRCPsych OSCE workshop which is less labour-intensive and cheaper to run. The workshop involves trainees first designing (with facilitation from the organisers) and then performing stations. Thus, the candidates gain useful insights into the specific topic areas assessed and the examiners' marking schemes, as well as practising clinical skills in a quasi-examination setting. However, the workshop's downside is that the trainees get to practise fewer stations than in a mock OSCE, without the provision of well-trained standardised patients.

We have adapted elements of the Naeem workshop, making them pertinent to the new examination format, and combined them with our experience of running mock OSCEs to create a 1-day CASC course (incorporating a mock examination). Attendees gain insights into the CASC format and marking schemes but also get ample practice doing stations.

Organising a mock CASC examination and course

Station design

The CASC scenarios were prepared in advance by four specialist registrar examiners (P.W., C.W., G.L.-S., L.C.), following a meeting with a senior consultant and medical educationalist (R.R.) to gauge the level of complexity required for CASC stations. A range of specialties covering a variety of clinical skills were selected in line with the College's blueprint for the CASC examination (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/MRCPsych%20CASC%20Blueprint.pdf). Instructions for the candidates, the standardised patients' and the examiners' constructs were prepared for each station, and peer-reviewed by all the organisers. Finally, they were collected together and printed in the same format to ensure a consistent appearance. Table 1 lists a synopsis of four of the stations and the core skills assessed in each (for a complete list of stations and core skills, see online Table DS1).

Table 1. CASC scenarios

| Scenarios | Skills assessed |

|---|---|

| Station A | |

| Pregnant woman who uses intravenous drugs | Substance misuse history taking with an elusive historian |

| The mother of a 12-year-old child with school refusal | Child and adolescent collateral history taking and empathic communication with an anxious parent |

| 70-year-old widow with Alzheimer's disease | Perform MMSE, assessment of suitability for anticholinesterase medication, and capacity assessment |

| Forensic patient with schizophrenia prior to possible move to less supported accomodation | History taking and detailed risk assessment |

| Station B | |

| Presentation of case to team consultant | Formulation of a risk assessment and short term management, including need for social services input |

| Discussion of case with child's head of year | Knowledge of methods for school reintegration and ability to act as child's advocate |

| Discussion of case with woman's son | Communication of capacity assessment and management plan in lay language. Knowledge of issues surrounding power of attorney |

| Presentation of case at CPA meeting | Presentation of history, risk assessment and management plan. |

| Knowledge of forensic services and potential problems arising from reduced support |

Standardised patients

Four standardised patients were selected from the OSCE role-player bank of one of the hospitals within our training scheme. All actors had received previous training and experience of psychiatry OSCEs at undergraduate and postgraduate level. At the start of the course the actors had a final ‘debrief’ with an examiner and any last-minute questions regarding the roles were clarified.

Venue and introduction

A venue with a main meeting room and smaller ‘break-out’ rooms close by was ideal for the CASC course. Comfort, plentiful refreshments and presentation aids were also essential. The day began with a 1-hour presentation (R.R., L.C.) detailing the format of the CASC and the clinical skills tested. The main differences and similarities between the CASC and OSCE were highlighted, as were ‘top tips for passing OSCEs’ (as many of the generic skills required for passing this format apply to the CASC as well).

Candidates

Eighteen candidates attended the course/examination. This was a good number to ensure that each trainee received sufficient practice doing stations. Larger numbers could have been facilitated but the organisers would have also needed to use more standardised patients and examiners. Half the attendees were male and the average age was 33 years (range 27–43). The candidates had completed on average 40.2 months (range 33–48) of training in psychiatry. Fifteen candidates (83%) had previously taken the MRCPsych Part 1 OSCE, whereas ten (56%) had experience of OSCEs in medical school. Sixteen (89%) candidates were taking the real CASC examination the following month.

CASC circuit

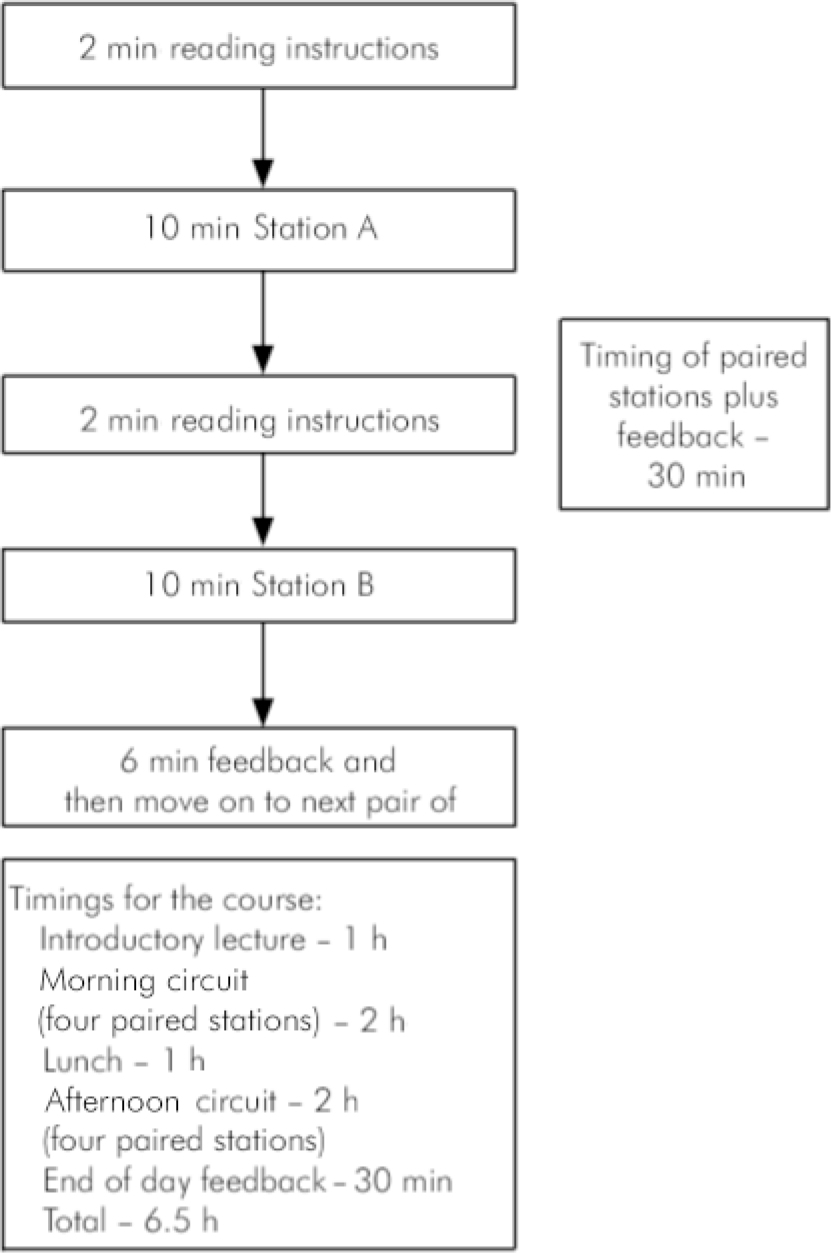

After a short break, the trainees convened in four small groups (maximum five trainees per group) in each of the break-out rooms. Strict timekeeping was observed by a separate member of the team, following the format of the real CASC examination. Both the candidates volunteering to be examined and their trainee peers were given copies of the candidate instructions. This allowed those observing to think about how they would structure their interview, if they were the ones being examined. In each pair of stations the standardised patient was interviewed in the first part, then the same candidate moved straight on to a separate follow-up set of instructions, directing the task to be delivered in the linked station. In the paired station, the examiner was ‘in role’ (e.g. a consultant psychiatrist, a schoolteacher), as well as scoring the candidate. In this way, over a 2-hour period all groups completed a ‘circuit’ of four paired stations (Fig. 1), offering four members of each group the chance to experience a mock CASC examination. The same process was repeated with a new circuit of four paired stations after lunch.

Marking scheme

In the first station, one of the organisers acted as an examiner as the candidate interviewed the standardised patient. In the paired station the organiser was both role-player and examiner. The examiners noted any ‘areas of concern’ and gave immediate feedback to the candidate (6 min at the end of the second station in the pair was feedback time). The standardised patient also briefly gave feedback on communication skills, and the candidate and their peers observing the process made additional comments. Standardised patients' feedback or scoring does not take place in the real CASC, as previous work has found a low level of agreement (kappa=0.4) between standardised patients' and examiners' scores in postgraduate psychiatry OSCEs (full details available from the author on request). However, it is useful for candidates to receive feedback from the standardised patient specifically relating to communication, as there is evidence suggesting higher agreement between standardised patients' and examiners' scores in this domain (full details available from the author on request).

Evaluating the CASC examination and course

CASC survey

At the end of the afternoon, candidates were asked to complete a questionnaire about their experiences of the mock CASC. This was before the course organisers gave overall feedback for the day, to reduce respondent bias. The questionnaire was a modified version of that constructed by Hodges et al (Reference Hodges, Regehr and Hanson1998) for the purposes of evaluating the acceptability of a postgraduate psychiatry OSCE. It has both quantitative (rating agreement/disagreement with statements on a 5-point scale) and qualitative (descriptions of opinions and experiences) elements. The quantitative component of the questionnaire required the candidates to answer seven questions relating to: fairness, difficulty, and realism of the CASC examination.

Fig. 1. Format and timings of the circuit and course.

The qualitative data were obtained from the candidates' written accounts of previous OSCEs and the current mock CASC examination. There was also a free-text space for general comments. The results from the statement ratings were analysed using Microsoft Excel; the data were subsequently content-analysed and arranged according to recurrent themes.

Survey results

Participants agreed (83%) or strongly agreed (17%) that the mock CASC was a fair assessment of skills required by the end of core specialist training. Table 2 reports the median responses to the individual statements of the questionnaire. On the whole, the candidates found the mock CASC to be an acceptable examination, but there were two issues that they were undecided about. First, although 28% agreed that there is no longer a need to use real patients in postgraduate clinical psychiatry examinations, 39% felt neutral about this, 28% disagreed and 5% strongly disagreed. Second, although 50% of candidates preferred the CASC format, 40% were neutral on the issue and 10% preferred the old Part 2 MRCPsych clinical examination.

Table 2. CASC survey1

| Statements (respondents, n=18) | Median response2 |

|---|---|

| 1. This mock psychiatry CASC was a fair assessment of clinical skills appropriate to ST3 level | Agree3 |

| 2. A competent psychiatry ST3 would pass this examination | Agree4 |

| 3. An incompetent ST3 would fail this examination | Agree4 |

| 4. The situations used reflect those that an ST3 in psychiatry would have to deal with | Agree4 |

| 5. The simulations by the actors were realistic | Agree5 |

| 6. There is no longer a need to use real patients in postgraduate clinical psychiatry examinations | Neutral6 |

| 7. I prefer this form of evaluation to the previous Royal College clinical examination involving a long case and patient management problems | Agree/neutral7 |

The results of a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the respondents' comments from the free-text part of the questionnaire are shown in Table 3. Most of the comments related to a comparison between the CASC and the OSCE format and the old MRCPsych Part 2 clinical examination, as this part of the questionnaire was designed to elicit this set of responses. In comparison with an OSCE, the CASC was felt to be more complex and required greater clinical skills to pass. However, although half of candidates thought the CASC was fairer and more standardised compared with the Part 2 clinical examination, a quarter believed it to be a more artificial format.

Table 3. Candidates' opinions about the CASC examination

| Responses, % (n=18) | |

|---|---|

| CASC compared with OSCE | |

| Positive | |

| More complex | 67 |

| More realistic | 11 |

| Greater focus need due to paired stations | 17 |

| Requires more knowledge | 11 |

| Requires more confidence | 11 |

| Tests management skills well | 17 |

| Less of a ‘box-ticking’ exercise | 5.6 |

| Negative | |

| More tiring | 11 |

| No difference | 5.6 |

| CASC compared with old Part 2 clinical examination | |

| Positive | |

| Fairer/more standardised | 56 |

| Broader range of skills tested | 5.6 |

| Negative | |

| More artificial | 28 |

| Greater time pressure | 22 |

Feedback from candidates after they took the real CASC

The mock examination was conducted before the real CASC took place. As this was a totally new format, the mock examination was designed according to the information provided by the College (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/MRCPsych%20CASC%20Blueprint%20.pdf) and what the authors anticipated the CASC would be like. However, in an effort to improve future mock examinations, informal feedback was sought from a number of trainees who attended the course and then subsequently took the CASC. This indicated that the real examination was not as complex as had been anticipated, and that it was more like the old Part 1 OSCE. In particular, the linked stations in the real CASC seemed more straightforward than the ones designed for the mock examination. For example, the candidates thought that explaining a diagnosis to a relative was a similar type of task to that previously required in the Part 1 OSCE, whereas the linked stations in the mock CASC dealt with more complex issues of management.

Discussion

A mock CASC examination and course can be organised by adapting already existing methods. Many MRCPsych courses in the UK have been running mock OSCEs, and are developing mock CASCs using consultants and other senior doctors as examiners and standardised patients from the local medical school bank. This is particularly true of urban psychiatry rotations, such as in London. However, on smaller schemes or those in more isolated parts of the country it may be more difficult to organise a mock CASC due to workforce and/or geographical reasons. The method described here would be easy to replicate locally and requires only small numbers of participants, standardised patients and organisers. On our course, we sufficed with four specialist registrars, one consultant and four standardised patients. The 18 candidates who attended rated the value of the course overall at between 7 and 10 (10 being excellent).

Most of the candidates on the course were taking the real examination within 1 month and therefore were highly motivated to participate fully. They reported finding the mock CASC examination tiring, and struggled to maintain concentration throughout the 24 min of each paired station and retain information gained from the first into the second one. This highlighted the need for practising these stations in examination conditions.

As examiners in this mock CASC examination, and previously in mock OSCEs, we saw the differences between the examinations from another point of view. The CASC has a similar set up to the old OSCE, and may be considered just an extension, but it was noticeable that the skills required are similar to those in the old Part 2 examination. In particular, presenting information in a professional and succinct way, and formulating and communicating a management plan, as would have been expected in patient management problems, are key skills required for the CASC. It was evident that those candidates who had prior experience of doing patient management problems in the old Part 2 clinical examination had an advantage over and above those who had only taken OSCEs previously. This may show that patient management problems have a place in examination practice.

Discussions about fitness of purpose are to be expected when there is any change to an examination format. Indeed, there is lively debate currently about the loss of the ‘long case’ in the final MRCPsych clinical examination (Reference Benning and BroadhurstBenning & Broadhurst, 2007). However, it is the College's intention that the problems associated with the long case (i.e. variability in complexity of patient presentation, a narrow range of skills assessed, specific problems such as a patient's communication on the day) will be eliminated with the introduction of the CASC examination.

We have some sympathy with the views of Benning & Broadhurst (Reference Benning and Broadhurst2007), who lament the ‘death’ of the long case. We had previously noted a decline in the performance of the first cohort of Part 1 OSCE candidates, compared with their predecessors, when they took the old Part 2 clinical examination (Reference Whelan and ChurchWhelan & Church, 2005). It was our experience of examining these candidates in a mock Part 2 clinical examination (arranged as part of our MRCPsych course) that they struggled to conduct an overall formulation of a long case. We believed this was due to the compartmentalised skills that they had acquired for passing the OSCE. Furthermore, it has been found that OSCE ‘checklists’ do not capture increasing levels of expertise (Reference Hodges, Regehr and McNaughtonHodges et al, 1999). However, the College seems to have recognised this by using a single score global marking scheme for each CASC station (in contrast to an OSCE checklist).

Conclusions

A mock CASC examination and course can easily be organised. The accompanying survey revealed generally favourable opinions that the trainees had towards the mock CASC examination. The majority (83%) had prior experience of the old Part 1 OSCE and so could make a fair comparison between the two examinations. Finding the new examination to be more complex than the Part 1 OSCE should be expected, as this is now the only clinical examination for the MRCPsych. In addition, though, we may have set the standard too high in our first mock CASC examination. Alternatively, the College may have made the first CASC too easy. Since we ran the course, the College changed the format of subsequent CASC examinations by using a mixture of paired stations and shorter (7-minute) single stations (similar to those used in the old OSCE format). It will be interesting to see the complexity level of future CASCs. On the whole, though, the opinions expressed in the survey were that CASCs are a fair means of examining trainees at the end of their core specialty training.

Declaration of interest

P.W., G.L-S, L.C., C.W. and R.R. are or recently have been organisers of the Guy's, King's and St Thomas' MRCPsych course, and teach on various MRCPsych examination preparation courses. R.R. is the editor of the College Seminar Series OSCE book and is preparing a CASC book for the same series. The mock examination course was funded by an educational grant by Eli Lilly.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the course participants for completing the survey.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.