Shortly after taking office in January 2017, US President Donald Trump issued Executive Order 13769, called ‘Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States’ (Trump Reference Trump2017). This order instituted a number of immigration restrictions, especially concerning immigration and travel from Muslim-majority countries to the United States. Explicitly referring to the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, DC, Trump (Reference Trump2017, 8977) argued that these restrictions were necessary because

[n]umerous foreign-born individuals have been convicted or implicated in terrorism-related crimes since 11 September 2001, including foreign nationals who entered the United States after receiving visitor, student, or employment visas, or who entered through the United States refugee resettlement program.

Thus the purpose of these immigration restrictions (which included suspending the issuance of visas and denying immigrants from certain countries entry into the United States) was ‘to protect the American people from terrorist attacks by foreign nationals admitted to the United States’ (Trump Reference Trump2017, 8977).Footnote 1

Trump's executive order is emblematic of how some politicians relate terrorism to immigration: migrantsFootnote 2 are regarded as a potential threat to domestic security given the chance they will engage in terrorist activity. In recent years, Muslim immigration in particular has been considered a security threat to Western societies (for example, Givens et al. Reference Givens, Freeman and Leal2009; Sides and Gross Reference Sides and Gross2013). Furthermore, as exemplified by Trump's travel ban, the ostensible relationship between terrorism and migration has public policy consequences. More generally, since the 9/11 attacks in the United States, many policy measures in fields such as surveillance, immigration and foreign policy have been justified with the security threat that immigrants ostensibly pose (for example, Chebel d'Appollonia Reference Chebel d'Appollonia2012; Davis and Silver Reference Davis and Silver2004; Givens et al., Reference Givens, Freeman and Leal2009; Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Norris, Kern and Just2002). Consequently, the alleged effect of migration on terrorism will also matter to electoral politics. For instance, Wright and Esses (Reference Wright and Esses2019) show that individuals who perceived immigrants as a security concern were more likely to vote for Donald Trump, who explicitly campaigned on an anti-immigration and tough-on-terror platform, in the 2016 US elections.

Motivated by recent political, electoral and security events such as the election and politics of Donald Trump, the rise of right-wing anti-immigrant parties in Europe and a number of high-profile terrorist attacks committed by migrants in the West (for example, the Paris attacks of November 2015 and the Berlin attack of December 2016), we provide a state-of-the-art overview of the literature on the migration–terrorism nexus.Footnote 3 Virtually all studies that address the relationship between migration and terrorism have been published over the last twenty years; many of them are only a few years old. The topic has attracted research interest in various fields such as economics, political science, sociology and social psychology. This allows us to consider the migration–terrorism nexus from various and complementary viewpoints. When reviewing the literature, we are interested in answering three (related) research questions:

(1) Does immigration lead to terrorism? In other words, is there empirical evidence to support the argument often raised in political and public debates that migration carries a risk to national security in the form of terrorism?

(2) What are the electoral consequences of terrorism? In particular, to what extent do terrorist attacks shape individual citizens' views about immigration and their electoral preferences?

(3) What is the relationship between terrorism and migration policy? Does terrorism lead to stricter migration policies, and do these measures, in turn, decrease the number of terrorist attacks a country experiences?

To answer these questions, we proceed as follows. After defining the term ‘terrorism’ and discussing its development across time and space, we review the literature that examines the role of migration as a potential cause of terrorism. Here, we also study how terrorism may be related to migration in origin countries. The next section focuses on the effects of terrorism in the destination countries. More specifically, we look at how terrorist attacks contribute to the politicization and framing of migration as a security issue by affecting attitudes towards immigrants, electoral behavior and migration policy making. The final section concludes.

Terrorism preliminaries

Definition of Terrorism

According to Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Enders and Sandler2011, 321), terrorism can be defined as ‘[…] the premeditated use or threat to use violence by individuals or subnational groups against noncombatants in order to obtain a political or social objective through the intimidation of a large audience beyond that of the immediate victims’.

According to this definition, terrorism is distinct from (1) unorganized forms of violent political protest (including riots, mob violence), (2) non-political acts of violence (such as violent crime, school shootings) and (3) violent repression by the government, that is, state terrorism (for example, in the form of torture). Terrorism may, however, overlap with large-scale civil wars, meaning that non-state actors may resort to both terrorism and more conventional guerilla warfare in certain conflicts at the same time (for example, Gaibulloev and Sandler Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler2019: 291–292; Krieger and Meierrieks Reference Krieger and Meierrieks2011; for a general introduction to terrorism studies, see Enders and Sandler Reference Enders and Sandler2011).

Domestic terrorism is ‘homegrown [so that] the venue, target, and perpetrators are all from the same country’ (Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler Reference Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler2011, 321), while transnational terrorism concerns more than one country. Prominent examples of transnational terrorism are the 9/11 attacks: the perpetrators hailed from several Middle Eastern countries, while the attacks occurred in the United States and victimized thousands of US and non-US citizens.

Since migrants are, by definition, foreign nationals, transnational terrorism is particularly relevant for the study of the nexus between terrorism and migration. Transnational terrorism can be divided into two categories: (1) terrorism carried out by immigrants (foreign nationals) in their destination country, directed either against the inhabitants and institutions of the destination country or against other foreign nationals and (2) terrorism committed by natives (inhabitants of the destination country) against immigrants.

Trends in Transnational Terrorism since 1995

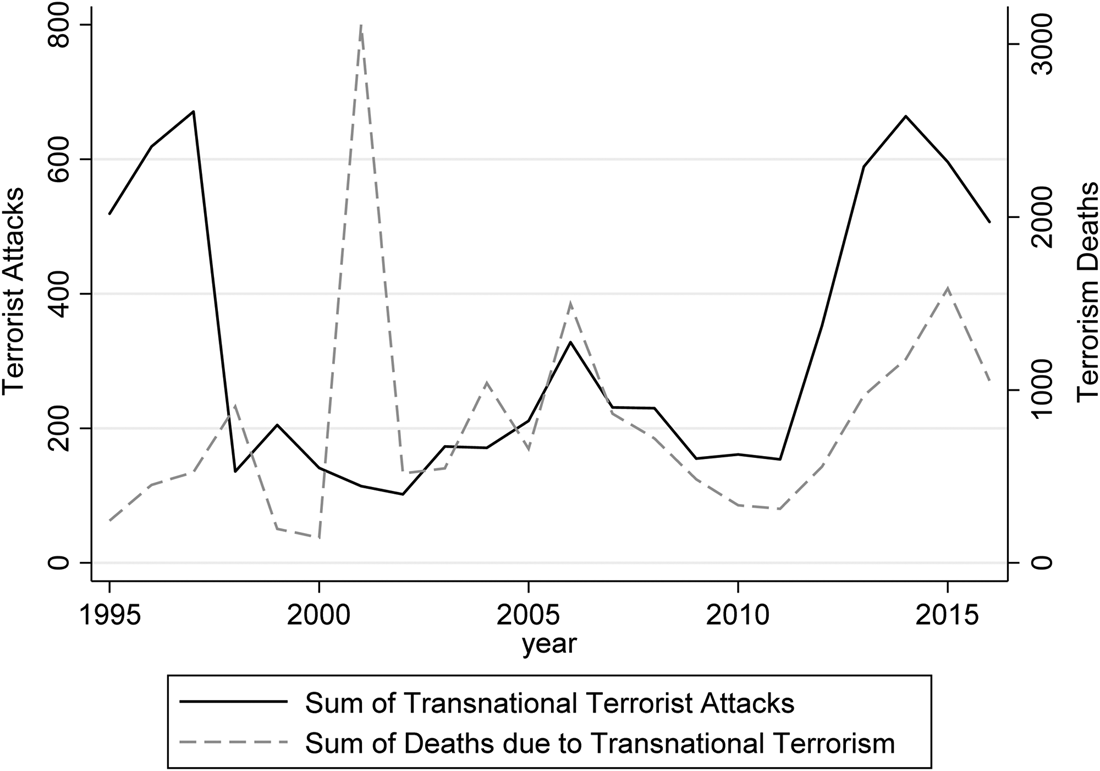

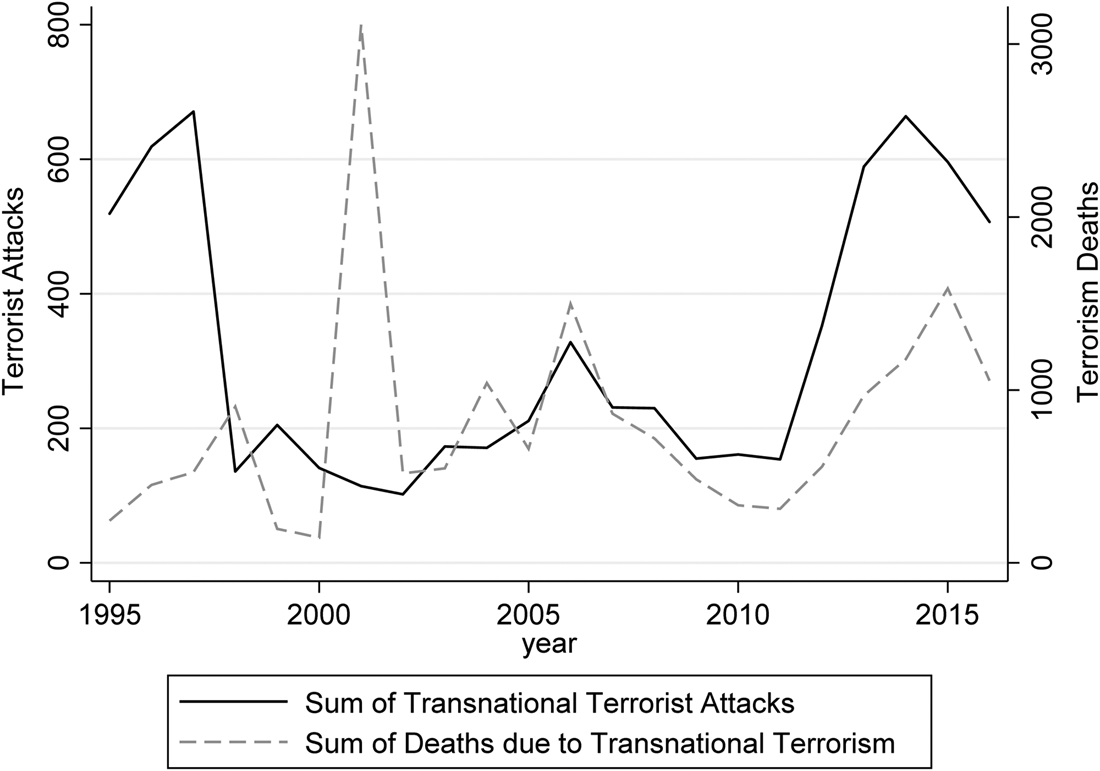

Figure 1 depicts global trends in transnational terrorism frequency and ferocity. The data used to construct this figure are drawn from Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler2011) and Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler2019). These authors use raw data from the Global Terrorism Database, first described in LaFree and Dugan (Reference LaFree and Dugan2007), applying various calibration and recoding methods to differentiate between domestic and transnational terrorism.Footnote 4 On average, between 1995 and 2016 there were approximately 320 transnational terrorist attacks with approximately 810 deaths per year. Transnational terrorism was fairly persistent with respect to its frequency and ferocity between the mid-1990s and 2010, with the noticeable exception of the spike in terrorism lethality in 2001 due to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It became more common and deadly after 2010.

Figure 1. Global trends in transnational terrorism, 1995–2016

Sources: Global Terrorism Database; Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler2011), Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler2019).

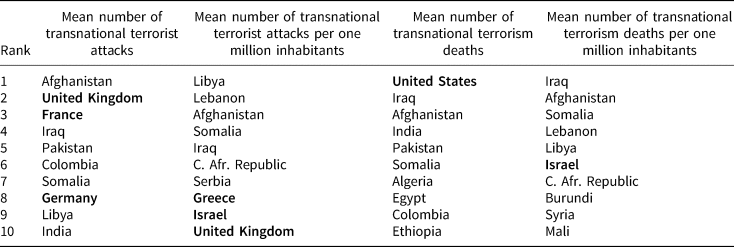

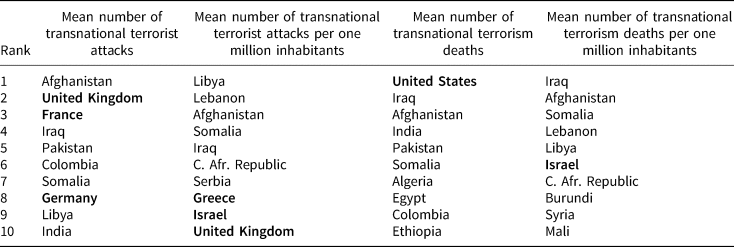

Table 1 shows that since the end of the Cold War, transnational terrorism has primarily affected countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. However, rich and industrialized (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD) countries have also been affected. Left-wing transnational terrorism has become less common after the end of the Cold War due to the loss of popular support for (and state sponsorship of) left-wing terrorist groups; however, pockets of this type of terrorism still exist, such as in Colombia (the ELN) and India (the Naxalites). Yet, post-1995 transnational terrorism has been much more strongly dominated by nationalist-separatist (for example, the Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës in Serbia/Kosovo) and especially religious-Islamist terrorist groups, for example, in Afghanistan (the Taliban), Iraq and Syria (Islamic State), Somalia (al-Shabaab) and Algeria (al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb). These trends in transnational terrorism are also described in more detail in Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler2019, 278–291).

Table 1. Geographical distribution of transnational terrorism, 1995–2016

Note: this list only considers countries that were always independent between 1995 and 2016 and that have more than one million inhabitants. Countries in bold were OECD members as of 2016.

Sources: Global Terrorism Database; Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Enders, Gaibulloev and Sandler2011), Gaibulloev and Sandler (Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler2019).

In sum, the stylized facts about transnational terrorism since 1995 tell us that (1) it concerns many parts of the world, particularly (2) many countries in Asia, Africa and the Middle East from which migration to Western countries originates, while (3) the overall risk of transnational terrorism (as expressed by its frequency and lethality) tends to be rather marginal, notwithstanding the ‘outlier’ of the 9/11 attacks.

Migration as a Cause of Transnational Terrorism

Theoretical Considerations

In this section, we discuss the empirical evidence on the potential effect of migration on terrorism. To theoretically understand how migration may affect terrorism, we employ a rational-choice model of terrorism. This model is the theoretical basis for many social science investigations of terrorism.Footnote 5 In short, it assumes that terrorists are rational actors who weigh the benefits of terrorism (such as achieving certain political goals) against its costs (for example, capture) and opportunity costs (for example, foregone earnings from non-violence when engaging in terrorism). Potential terrorists opt for violence (non-violence) when the benefits of terrorism outweigh its costs (benefits).

Migration may affect this terrorist calculus in two ways. First, it may make terrorism less costly. For instance, foreign terrorist organizations can use existing migration networks and routes to get terrorist operatives (for example, in the form of ‘sleeper cells’) into foreign countries at low costs, making subsequent terrorist activity by these operatives more probable. Similarly, foreign terrorist organizations can potentially rely on existing migrant communities in destination countries, so-called diasporas. Diasporas can be considered networks that provide their members with social bonds that produce mutual emotional and social support and reinforce common identities (for example, Sageman Reference Sageman2004). Terrorist organizations linked to these diasporas (for example, due to a shared religious or ethnic background) can exploit these pre-existing networks for the purpose of radicalization, recruitment, financing, intelligence gathering and as safe havens (for example, Sageman Reference Sageman2004, Reference Sageman2011; Sheffer Reference Sheffer and Richardson2006). This ought to lower the operating costs of terrorist organizations and thus make terrorism – ceteris paribus – more likely.

Secondly, these very diasporas and migrant communities may also be subject to discrimination in destination countries such as in the form of religious intolerance or exclusion from the labor market or political representation (for example, Sheffer Reference Sheffer and Richardson2006). Discrimination is a powerful predictor of terrorism (for example, Piazza Reference Piazza2012; Saiya Reference Saiya2019). It makes terrorism a more attractive option by lowering its opportunity costs, for example as opportunities for non-violent economic or political participation are constrained. Consequently, as migration leads to the growth of diasporas, it may also lead to the growth of grievances (due to discrimination) that could fuel terrorist violence by migrants.

The Effect of Migration on Terrorism in Destination Countries

Three large-N studies investigate the effect of migration on terrorism in the destination country of migration. First, Bove and Böhmelt (Reference Bove and Böhmelt2016) study this relationship for a sample of 145 countries between 1970 and 2000. They find that increases in migrant inflows lead to fewer terrorist attacks. Secondly, Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) examine migration from 183 origin to 20 OECD countries in a dyadic setting and come to the opposite conclusion: a larger number of foreigners leads to more terrorist activity in the host country. Thirdly, Forrester et al. (Reference Forrester2019) use bilateral migration data for 170 countries (thereby also including South–South migration) between 1995 and 2015, and find no evidence that immigration leads to more terrorism in destination countries.

Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) argue that their finding of a positive effect of immigration on terrorism is a mere consequence of scale effects. It is well known from the literature on the determinants of terrorism that more populous countries experience more terrorist activity simply due to a larger pool of (potential) terrorist recruits and terrorist victims (for example, Krieger and Meierrieks Reference Krieger and Meierrieks2011). Indeed, Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) show that the effect of foreign population growth on terrorism is not different from the effect of domestic population growth, meaning that immigration does not disproportionately undermine security. At the same time, this suggests that other theoretical mechanisms that could explain the link of migration and terrorism (for example, lower infiltration and operating costs of terrorist groups or support from diasporas) are not at play.

This leaves little evidence from large-N studies in favor of the hypothesis that immigration unconditionally promotes terrorism in receiving countries. However, we can use the results of Bove and Böhmelt (Reference Bove and Böhmelt2016), Forrester et al. (Reference Forrester2019) and Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) as well as those of Böhmelt and Bove (Reference Böhmelt and Bove2020a) to think about the conditional effects of immigration on terrorism in a number of ways.

First, the composition of the migration influx may matter to the migration–terrorism relationship. While Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) do not find that the gender mix of migration plays a role, they are able to show that high-skilled immigration actually reduces the risk of terrorism. For instance, more educated migrants may be more likely to integrate into destination country societies, thus having fewer reasons to resort to terrorism (due to the high opportunity costs of terrorism). In a similar vein, Bove and Böhmelt (Reference Bove and Böhmelt2016, 586) argue that their result of a negative effect of immigration on terrorism may be due to ‘side effects of human capital’, since high-skilled individuals are usually over-represented in migration flows.Footnote 6 For example, high-skilled individuals may find it easier to participate in the labor markets of destination countries; this will result in higher opportunity costs of terrorism and – ceteris paribus – lower levels of participation in terrorism.

Secondly, the origin of migrants may also play a role. Prior research in this area focuses on the influx of migrants from (1) Muslim-majority countries (given the rise and thus possible ‘import’ of religious-Islamist extremism) and (2) conflict- and terror-ridden countries (given the potential dangers of ‘importing’ foreign conflict). With regard to Muslim migration, both Forrester et al. (Reference Forrester2019) and Dreher, Gassebner, and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) find that migration from Muslim-majority countries is not systematically associated with more terrorism in receiving countries. The evidence is somewhat more divided when it comes to the role of migration from conflict-ridden states. Bove and Böhmelt (Reference Bove and Böhmelt2016) find that migration from conflict-ridden countries can be an important vehicle for the diffusion of terrorism. Bove and Böhmelt (Reference Bove and Böhmelt2016, 576) argue that ‘migration flows from terrorism-prone countries facilitate the diffusion of terrorism in the host country by providing a dense framework of prior trusted relationships among the migrants’ that terrorist organizations can exploit for recruitment and radicalization, given a shared national, ethnic or religious background of terrorist group and diaspora members. However, they also note that while their results indicate that terrorism may travel from one country to another via migration, this migration – beyond the diffusion channel – will not need to automatically lead to more terrorism in destination countries (Bove and Böhmelt Reference Bove and Böhmelt2016, 585). Indeed, using migration from terror-prone countries as a predictor and thus testing the total effect of emigration from conflict-prone countries, neither Forrester et al. (Reference Forrester2019) nor Dreher, Gassebner, and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) find evidence that migration from conflict-intense countries shares a special relationship with terrorism in receiving countries.

Thirdly, conditions in the destination country may also affect the migration–terrorism nexus. In particular, conditions that are conducive to immigrants' integration can reduce the risk of terrorism committed by migrant populations. Studying migration into OECD countries between 1980 and 2010, Böhmelt and Bove (Reference Böhmelt and Bove2020a) find that cultural proximity between the migrants' home and destination countries reduces the cross-border diffusion of terrorism. Here, similar identities and values may facilitate integration and reduce the incentives to engage in terrorism against the host country (Böhmelt and Bove Reference Böhmelt and Bove2020a). This suggests that while cultural proximity ought to lower the costs of terrorist infiltration, this effect is outweighed by its concurrent effect on integration, which ought to increase the opportunity costs of terrorism.

Refugee Migration and Terrorism in Host Countries

While previous empirical studies have examined the general relationship between migration and terrorism, another set of studies examine the relationship between involuntary migration and terrorism. Three large-N studies by Choi and Salehyan (Reference Choi and Salehyan2013), Milton, Spencer and Findley (Reference Milton, Spencer and Findley2013) and Polo and Wucherpfennig (Reference Polo and Wucherpfennig2019) investigate the effect of refugee inflows on terrorism in the receiving country.

Choi and Salehyan (Reference Choi and Salehyan2013) use data for 154 countries for the years 1970–2007, and find that countries that host refugees are more likely to experience terrorist activity. They argue that this relationship can be explained by poor conditions in refugee camps that make participation in terrorist violence more attractive. Similarly, Milton, Spencer and Findley (Reference Milton, Spencer and Findley2013), using a dyadic framework, show that refugee flows significantly increase transnational terrorism that occurs in the host country. As in Choi and Salehyan (Reference Choi and Salehyan2013), they argue that this unfavorable relationship can be explained by the poor treatment of refugees in host countries in general and harsh conditions in refugee camps in particular. Both transmission channels would imply comparatively low opportunity costs of terrorism, for example, as the possibilities of refugee participation in the labor market are limited. By contrast, Polo and Wucherpfennig (Reference Polo and Wucherpfennig2019) challenge the notion that hosting refugees leads to more terrorism against nationals of the host country. They claim that any increase in terrorism due to the inflow of refugees that is observed at the country level is due to scapegoating – that is, refugees becoming the target (rather than the perpetrators) of terrorism.

Refugee migration is a special kind of migration. Indeed, the evidence on the effect of refugee migration on terrorism helps more clearly identify the conditions under which migration more generally may result in increased terrorist activity in several ways. First, refugee migrants are less likely to self-select into migration, meaning that – in contrast to voluntary labor migration – the educated are less likely to be over-represented. The (relative) lack of human capital endowment of refugees may complicate their economic and social integration into host societies and thus make refugee migrants – in contrast to more educated labor migrants – more vulnerable to politico-economic hardship and discrimination. This could ultimately lead to terrorism by refugees as a means to voice dissent and achieve politico-economic relief. Secondly, by definition, refugee migrants predominantly come from countries affected by conflict and repression (for example, Echevarria and Gardeazabal Reference Echevarria and Gardeazabal2016). This may make it more likely that terrorist organizations can recruit refugees into their ranks, ‘weaponizing’ the refugees' experience with violence in their host country. Thirdly, the conditions under which refugees live in their host countries are usually less conducive to integration compared to regular migrants. For instance, refugee camps are important breeding grounds of refugee terrorism, but voluntary labor migrants would not live in such camps. This again speaks to the idea that the treatment of migrants (for example, in terms of immigration and integration policies) can condition the effect of migration on terrorism. Indeed, Polo and Wucherpfennig (Reference Polo and Wucherpfennig2019) show that refugees will not attack nationals of their host country especially in developed countries, presumably because refugees are treated better in richer countries. Similarly, Böhmelt, Bove and Gleditsch (Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Gleditsch2019a) show that while a refugee influx may fuel domestic conflict between refugees and locals, this effect is especially prevalent in countries characterized by low levels of state capacity (such as those with a weak state bureaucracy). This latter effect is especially relevant to the refugee migration–terrorism nexus, as refugee flows tend to cluster in the direct neighborhood of conflict-ridden countries; these countries in turn also tend to lack sound institutions and economic resources to effectively manage these refugee flows.

Terrorism against Migrants in Destination Countries

Migrants may not only be the perpetrators of terrorism; they may also be its victims. The native population may respond to (increased) immigration with fear and hostility. For example, migrants can be perceived as labor market competitors, burdens to domestic welfare systems or threats to native cultural identity (for example, McAlexander Reference McAlexander2020). Applying a rational-choice model of terrorism, the inflow of migrants can make anti-immigrant terrorism more likely because (1) there is a larger pool of potential targets (which lowers the costs of carrying out anti-immigrant violence) and (2) immigration may lower the opportunity costs of anti-immigrant violence for host country locals (for example, as labor market competition crowds out part of the native population). Migrants and refugees may also be scapegoated when they can be linked (for example, due to religious or ethnic affiliation) to external terrorist threats that are relevant to the host country's native population (Polo and Wucherpfennig Reference Polo and Wucherpfennig2019). Through these pathways, terrorism against non-natives can become more likely as immigration increases. This ought to especially pertain to right-wing terrorism, which is usually animated by rabid nativism and xenophobia.

Indeed, empirical evidence by McAlexander (Reference McAlexander2020) on a set of Western European countries between 1980 and 2004 strongly suggests that a larger number of refugees and non-European immigrants is associated with more right-wing terrorist activity. Interestingly, he finds no evidence that migration flows affect left-wing terrorism in a similar manner, which indicates that it is indeed only a specific sub-set of terrorism that responds to migration. This finding is complemented by the large-N evidence of Polo and Wucherpfennig (Reference Polo and Wucherpfennig2019, 3), who show that refugee stocks from countries that experience terrorist activity are more likely to be victimized by right-wing terrorism in their host country, suggesting that these refugees are perceived as security threats and thus scapegoated by the native population.

Given a lack of further large-N evidence, we can supplement the aforementioned results by looking at evidence from Germany on the relationship between immigration and right-wing violence. Germany is an interesting case study because it experienced two periods of increased immigration after the end of the Cold War (the early 1990s and the post-2015 period) that were also accompanied by a marked increase in right-wing violence.Footnote 7 Indeed, Krueger and Pischke (Reference Krueger and Pischke1997), Koopmans and Olzak (Reference Koopmans and Olzak2004), and Braun and Koopmans (Reference Braun and Koopmans2010) provide statistical evidence that the number of foreigners, immigrants, and asylum seekers at the regional or state levels in Germany was linked to more right-wing violence against foreigners and immigrants in the 1990s, especially in East Germany. Similarly, investigating the post-2015 period that was characterized by a record influx of refugees into Germany, Jäckle and König (Reference Jäckle and König2017, Reference Jäckle and König2018) find that the strength of right-wing parties in a district as well as anti-immigrant rhetoric, partly prompted by terrorist attacks in neighboring countries, considerably boosted the probability of attacks on refugees in the areas under study. In other words, their studies suggest that ideological predispositions determine how locals respond to (increased) immigration.

While limited, the empirical evidence thus suggests that (1) migrants can indeed be victimized and (2) anti-migrant terrorism is primarily committed by right-wing groups. In light of these findings, the results of Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) could point to a vicious circle between anti-immigrant terrorism and terrorism by migrants. They show that terrorist attacks against foreigners in their host countries increase the risk that foreign populations will likewise resort to terrorism.

The Migration–Terrorism Nexus in the Origin Countries of Migration

The migration–terrorism nexus may also be related to the origin countries of migration in two ways: (1) terrorism may be a cause of out-migration and (2) communities of migrants in foreign countries may influence terrorist conflicts in their home countries.

Concerning terrorism as a cause of population out-flows, domestic conflicts obviously trigger forced or refugee migration (for example, Echevarria and Gardeazabal Reference Echevarria and Gardeazabal2016). However, terrorism may also affect voluntary labor migration. Dreher, Krieger and Meierrieks (Reference Dreher, Krieger and Meierrieks2011) consider labor migration from 152 countries to the OECD between 1976 and 2000, and find that more terrorist activity in origin countries leads to more high-skilled migration to OECD countries. They argue that terrorism reduces economic opportunities at home (for example, by adversely affecting trade and foreign investment) and therefore decreases the returns to education, making it more attractive to migrate, especially when one is highly educated. This large-N evidence is complemented by the results of Belmonte (Reference Belmonte2019), who studies the effect of (separatist) terrorism in South Tyrol on out-migration. He similarly finds that skilled workers are more likely than unskilled workers to leave areas that are exposed to terrorist attacks.

After migration or flight, diasporas in foreign countries may still influence terrorist activity in their home countries. For instance, migrants may send money to support terrorist groups at home. Indeed, Mascarenhas and Sandler (Reference Mascarenhas and Sandler2014) show that such remittances are linked to more terrorist activity in the remittances-receiving country, suggesting that these types of payments help fill the war chests of terrorist organizations that are active in the migrants' home country. In a similar vein, Piazza (Reference Piazza2018) studies how transnational ethnic diasporas affect the resolution of campaigns by terrorist groups to which these diasporas are linked. He finds that such terrorist campaigns are less likely to end (for example, through military means or the political process) than campaigns without diaspora links, arguing that diasporas provide material support to sustain them.

Given their importance as potential reservoirs of material support, diasporas are also important audiences for terrorist groups that depend on their support. Here, Piazza and LaFree (Reference Piazza and LaFree2019) find that Islamist terrorist organizations are more likely to refrain from high-casualty terrorism when they are dependent upon diaspora backing. They argue that such acts will adversely affect diaspora communities when they can be linked to these attacks (for example, because such attacks increase fear and distrust against them in their host countries), leading terrorist organizations to forego such attacks to protect their diaspora support.

The Effects of Terrorism on Attitudes Towards Immigrants, Electoral Behavior and Immigration Policies

Theoretical Framework

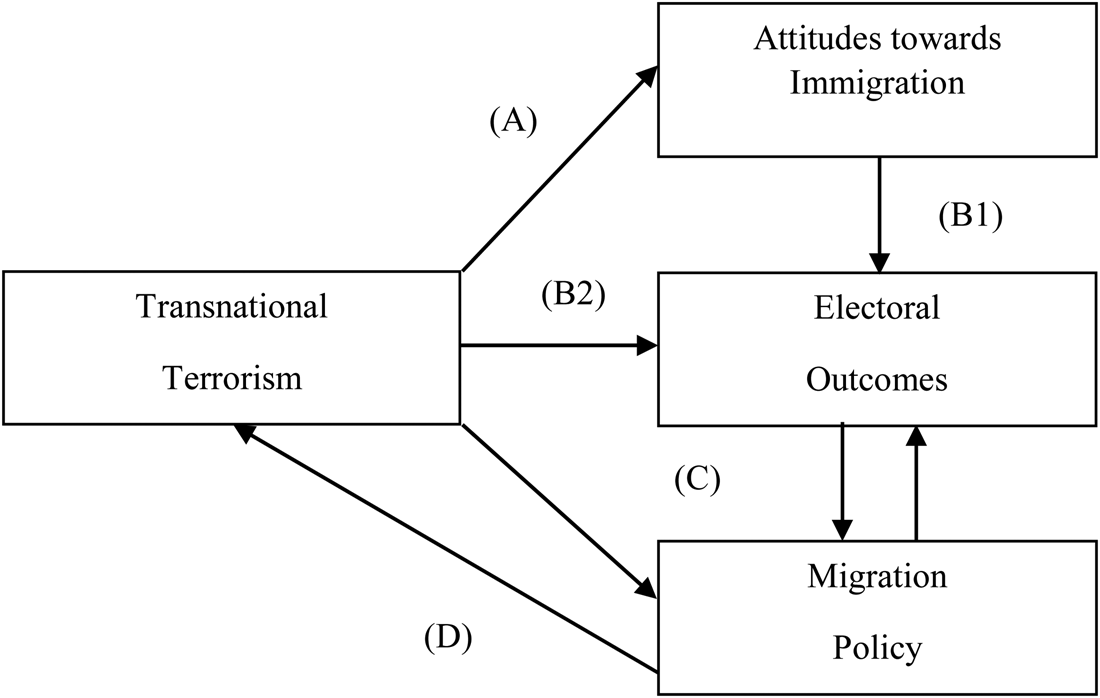

In this section, we examine the effects of terrorism in destination countries in the context of three interrelated linkages: (1) the effect of terrorism on natives' attitudes towards immigration, (2) the effect of terrorism on electoral outcomes and (3) the role of terrorism in migration policy making.

Figure 2 outlines a theoretical framework consisting of the main elements and their relationships as they are discussed in the literature. First, it illustrates that transnational terrorism might affect public perceptions of (and attitudes towards) immigrants and migration (A). More precisely, fear and actual or perceived threats from transnational terrorism might translate into stronger anti-immigration sentiment; these sentiments may be triggered by transnational terrorism in one's home country as well as in neighboring or far away countries. Secondly, anti-immigrant sentiment ought to fuel support for (right-wing) anti-immigrant political parties. This may reduce the re-election chances of governments with different ideological orientations (B1). Terrorism may also affect electoral outcomes through other pathways (B2), for example by reducing economic activity and life satisfaction in targeted countries. These effects may further reduce the electoral success of incumbent governments. By endangering their political survival, transnational terrorism consequently creates powerful incentives for governments to enact more restrictive migration policies (C). Governments may expect harsher policies to serve as a political signal to the electorate and thus siphon off political support for right-wing or opposition parties. At the same time, restrictive migration policies may help reducing transnational terrorist activity (D). For instance, stricter immigration policies may increase the costs of terrorist infiltration and thus reduce the level of terrorist activity directed against the country pursuing such policies. By reducing (future) transnational terrorism, governments may be able to restore electoral confidence and limit economic damage due to terrorism, further increasing the government's chances of political survival.

Figure 2. Theoretical framework

Terrorism's Effects on Attitudes towards Immigrants

In general, we expect attitudes towards immigrants to become more negative in the context of terrorism. Actual or perceived threat is one of the most important explanatory factors for such attitudes or changes in attitudes (for example, Huddy et al. Reference Huddy2005). That is, terrorism is perceived as a threat to personal and national security; this leads to heightened fear of the other, increased ethnocentrism, prejudice and xenophobia as well as stronger ties to native identity, all of which, in turn, promote more negative attitudes towards migrants (for example, Hellwig and Sinno Reference Hellwig and Sinno2017; Hitlan et al. Reference Hitlan2007; LeVine and Campbell Reference LeVine and Campbell1972; Schimel et al. Reference Schimel1999).

A first group of studies investigates the effects of terrorism on attitudes towards immigrants in the context of the 9/11 attacks. The evidence indicates that these attacks affected Americans' feelings of security and led to higher levels of fear and anxiety (for example, Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Norris, Kern and Just2002; Huddy, Khatib and Capelos Reference Huddy, Khatib and Capelos2003). What is more, a number of studies found that in the wake of these attacks, prejudices and discrimination against Muslims increased in many Western states (for example, Allen and Nielsen Reference Allen and Nielsen2002; Echebarria-Echabe and Fernandez-Guede Reference Echebarria-Echabe and Fernandez-Guede2006; Sheridan Reference Sheridan2006). This increase in xenophobia and Islamophobia in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks also coincided with more negative views on immigration not only in the United States but also in other Western countries. For instance, Aslund and Rooth (Reference Aslund and Rooth2005) show that negative views on immigrants increased in Sweden after the 9/11 attacks. In Germany, more people supported a reduction in immigration after the attacks (Noelle-Neumann Reference Noelle-Neumann2002). Schüller (Reference Schüller2016) studies panel data and observes a shift towards more negative attitudes toward immigration and a decrease in concerns over xenophobia in Germany in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks.

Some evidence indicates that the adverse effect of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on prejudices and xenophobia was rather short-lived. Panagopoulos (Reference Panagopoulos2006) finds that prejudices increased in the United States after the 9/11 attacks but receded to pre-9/11 levels shortly thereafter. Similarly, Kalkan and Uslaner (Reference Kalkan, Uslaner and Helbling2012) found no important changes in Islamophobic attitudes in the United States when comparing the pre- and post-9/11 period. Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2010) provides the most convincing test of the effect of the 9/11 attacks on immigration attitudes. He investigates panel survey data from the fall of 2000, October 2001 and March 2002. He finds an important short-term impact on attitudes toward immigrants: respondents were more likely to agree with the assessment that immigrants have become too demanding in the aftermath of the attack. While this change in attitudes implies increased hostility towards migrants, Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2010) also shows that these changes in attitudes had already receded by March 2002.

While almost all studies that investigate effects on attitudes due to 9/11 compare survey data before and after the attacks, a second group of studies takes advantage of attacks that occurred during the field phase of surveys. Boomgaarden and De Vreese (Reference Boomgaarden and de Vreese2007) and Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam (Reference Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam2011) use this quasi-natural experimental research design to investigate the effects of the assassination of the Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh by a radical Islamist in 2004. Here, Boomgaarden and De Vreese (Reference Boomgaarden and de Vreese2007) rely on their own survey data from the Netherlands, and find that while the murder did not affect general attitudes towards immigrants, immigrants and immigrants' religion were nevertheless more likely to be considered cultural or security threats. Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam (Reference Finseraas, Jakobsson and Kotsadam2011) use data from the European Social Survey (ESS) to show that preferences for more restrictive immigration policies increased. However, this was not the case for the Netherlands but for three of the 17 other European countries in the study. This finding, similar to evidence compiled on the 9/11 attacks, suggests substantial heterogeneity in and the potential cross-border diffusion of terrorism-induced anti-immigration views.

Finseraas and Listhaug (Reference Finseraas and Listhaug2013) and Legewie (Reference Legewie2013) examine similar cross-border effects of terrorism. In both papers, ESS data on attitudes towards migrants in European countries is correlated with large-scale terrorist attacks outside the Western world in quasi-natural experiments. For the 2008 Mumbai attacks (India), Finseraas and Listhaug (Reference Finseraas and Listhaug2013) find an increasing fear of terrorism but no increasing support for illiberal immigration policies among European respondents. Focusing on the 2002 Bali attacks (Indonesia), Legewie (Reference Legewie2013) finds that attitudes towards immigrants became more negative after the attacks. However, this effect was limited to three out of nine investigated countries and disappeared after approximately one month.

The evidence so far suggests that (1) while terrorism can negatively affect attitudes towards migrants, leading to more hostility among the native population, (2) these effects tend to be short-lived and not uniform across countries. Also, (3) terrorist activity in one country may affect – via media coverage and other communication networks – immigration attitudes in other countries.

These findings are corroborated by a third group of very recent empirical studies that examine the effects of large-scale terrorist attacks in Europe and the United States. The most prominent example is the November 2015 Paris attacks in which 130 people were killed at the Saint-Denis football stadium, several restaurants and especially the Bataclan concert hall. Jungkunz, Helbling and Schwemmer (Reference Jungkunz, Helbling and Schwemmer2019) investigate the impact of the 2015 Paris attacks with a German student sample and differentiate between attitudes towards immigrants that could be related to the attacks (Muslims) and those that could not (Christian). They find that attitudes towards Muslims became more negative among right-wing but not left-wing students; attitudes towards Christian refugees were not affected. Once again, this suggests terrorism has heterogeneous effects on attitudes. Van Assche and Dierckx (Reference Van Assche and Dierckx2019) use a student and a convenience sample in Belgium to investigate the effects of the 2015 Paris and 2016 Brussels attacks. They find no changes in attitudes towards different out-groups among respondents. Boydstun, Feezell and Glazier (Reference Boydstun, Feezell and Glazier2018) come to a similar conclusion when studying Americans’ feelings towards Muslims after the 2015 attacks in Paris and San Bernardino; they find that these attacks had no discernible effects on attitudes. Finally, Mancosu, Ferrin and Cappiali (Reference Mancosu, Ferrin and Cappiali2018) investigate the effect of the 2017 Manchester bombings in the UK. While they find that these attacks led to a negative response (increased stereotyping) towards immigrants and refugees in the immediate aftermath of the attack, this effect disappeared after a few days.

Several empirical studies also test for the existence of cross-border spillover effects of terrorism on attitudes, and study the role of contextual factors in shaping such effects. Analyzing Eurobarometer data from twenty-eight countries in November 2015, Ferrin, Mancosu and Cappiali (Reference Ferrin, Mancosu and Cappiali2020) find that the Paris attacks had a negative effect on attitudes towards immigrants, especially for educated and left-wing respondents in countries with a more positive political climate towards immigrants. According to them, such attacks especially affected people whose stereotypes were disconfirmed. Castanho (Reference Castanho2018) looks at the same data and investigates potential backlash and polarization effects. To strengthen the robustness of his analyses, he also evaluates ESS data that were in the field in January during the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris. He finds no important changes in immigration preferences. Using the same Eurobarometer data, Nussio, Bove and Steele (Reference Nussio, Bove and Steele2019) show that terrorism leads to increases in negative attitudes towards migrants and refugees, particularly in countries that have a relatively low immigrant population. Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio (Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio2020) test the proximity argument, which maintains that proximity to terrorism (even in other countries) will increase the likelihood of responding to it due to a heightened fear of terrorism. Using a sample that includes all terrorist attacks in Europe between 2003 and 2017, they come to the conclusion that terrorism both at home and abroad leads to more negative attitudes towards immigrants.

Impact of Terrorism on Electoral Outcomes

By fueling support for anti-immigrant sentiment among natives, transnational terrorism may be conducive to the electoral success of populist and mainstream right-wing parties that oppose immigration (Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). Indeed, there is considerable evidence that negative attitudes towards immigrants increase support for these types of political parties (for example, Coffé and Voorpostel Reference Coffé and Voorpostel2010; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2007; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2008; Oesch Reference Oesch2008).

For Turkey, Kibris (Reference Kibris2011) shows that the number of police forces killed at the district level between 1991 and 1995 by the Kurdistan Workers' Party led to increased support for right-wing parties. Similarly, focusing on Israel, Berrebi and Klor (Reference Berrebi and Klor2008) show that right-wing parties receive more votes when Israeli localities are affected by terrorism. In a similar vein, Getmansky and Zeitzoff (Reference Getmansky and Zeitzoff2014) find that right-wing support increases in areas in Israel that are affected by rocket attacks from the Gaza Strip. There is an effect even if localities are not targeted but lie within the rockets' range. Thus the mere risk of being victimized tends to change voting behavior in favor of right-wing parties.

While some evidence plausibly links terrorism, anti-immigrant views and electoral outcomes, it remains circumstantial, as the role of anti-immigrant views in the nexus between transnational terrorism and right-wing voting has not been directly tested. Right-wing parties may also plausibly benefit – more generally – from tough-on-terror and law-and-order stances after terrorist attacks, which complicates interpretations of how strongly anti-immigrant views induced by terrorism contribute to overall right-wing success at the voting booth.

At the same time, the literature on electoral accountability and retrospective voting suggests that evaluations of the incumbent government also affect election outcomes (for example, Barro Reference Barro1973; De Vries and Giger Reference De Vries and Giger2014; Ferejohn Reference Ferejohn1986). Healy and Malhotra (Reference Healy and Malhotra2013) provide an overview of the literature. Importantly, terrorism is expected to adversely affect economic conditions in affected countries, for example by depressing trade and investment (for example, Blomberg, Hess and Orphanides Reference Blomberg, Hess and Orphanides2004; Gaibulloev and Sandler Reference Gaibulloev and Sandler2019: 316–320; Meierrieks and Gries Reference Meierrieks and Gries2013). By adversely affecting economic growth and producing fear and stress, terrorism is also anticipated to reduce overall life satisfaction (for example, Farzanegan, Krieger and Meierrieks Reference Farzanegan, Krieger and Meierrieks2017; Frey, Luechinger and Stutzer Reference Frey, Luechinger and Stutzer2009). Through these effects, terrorism ought to lead to an unfavorable evaluation of the incumbent government's performance and thus make the electoral success of incumbent governments less likely.

Indeed, there is evidence that the electorate might hold the government accountable for terrorism and punish them at the ballot box. For instance, national elections took place in Spain in March 2004, only three days after bombs exploded in several commuter trains in Madrid, killing almost 200 people. Bali (Reference Bali2007) finds that these attacks influenced turnout and voting decisions and led to the replacement of the incumbent government. Gassebner, Jong-A-Pin and Mierau (Reference Gassebner, Jong-A-Pin and Mierau2008) find that the Spanish experience can be generalized. In a study of 800 elections in 115 countries between 1968 and 2002, they show that terrorism increases the probability of government replacement after an election, and the severity of the terrorist attack amplifies this effect. It is also possible that terrorism can promote government support and thus its re-election chances via a rally effect. For instance, Hetherington and Nelson (Reference Hetherington and Nelson2003) show that the US government benefitted from such a rally effect after the 9/11 attacks. However, rally effects appear to be rather elusive, which explains why governments will ultimately be more likely to be voted out of office after a terrorist attack (Gassebner, Jong-A-Pin, and Mierau Reference Gassebner, Jong-A-Pin and Mierau2008).

In sum, terrorism may affect voting behavior and electoral outcomes by (1) strengthening anti-immigrant sentiment and thus benefitting right-wing (anti-immigration) parties and (2) inducing adverse socio-economic shocks that reduce voter satisfaction with the incumbent government. This creates powerful incentives for incumbent governments to introduce more restrictive immigration policies. Indeed, we have reason to believe that the introduction of new immigration policies affects political parties’ electoral support. For instance, while not accounting for transnational terrorism, Abou-Chadi and Helbling (Reference Abou-Chadi and Helbling2018) demonstrate that both restrictive and liberal policy reforms affect issue voting.

There are two reasons why implementing more restrictive immigration policies may help incumbent governments. First, more restrictive immigration policies may satisfy public demand for policies that increase safety, especially when terrorism and immigration policies are linked in the public discourse (for example, Huysman Reference Huysmans2006; Messina Reference Messina2014). This, in turn, is expected to contribute to electoral success. For instance, Wright and Esses (Reference Wright and Esses2019) show that individuals who linked terrorism to immigration and consequently perceived immigration as a security threat were more likely to vote for Donald Trump, who explicitly campaigned on an anti-immigration platform, in the 2016 US elections. Secondly, predictions from a rational-choice model of terrorism suggest that implementing harsher immigration policies will increase the costs of terrorism (for example, by making it more difficult to launch cross-border attacks), thereby reducing future levels of terrorist activity directed against the country pursuing such policies. This ought to limit socio-economic damage due to terrorism and thus restore electoral confidence, therefore increasing the re-election chances of incumbent governments.

Effects of Terrorism on Immigration Policies

The logic of political survival would seem to suggest that incumbent politicians will respond to transnational terrorism (that is, terrorism by foreign nationals) by introducing more restrictive immigration policies.Footnote 8 This is because citizens – either due to increased fear, stronger anti-immigrant sentiment or due to economic anxiety when facing the socio-economic costs of terrorism – are likely to demand more restrictive immigration policies and vote for political parties that promise such policy changes.

Indeed, a number of analysts have found that immigration policies became more restrictive in response to the 9/11 attacks. For instance, Waslin (Reference Waslin, Givens, Freeman and Leal2009) discusses the negative effects of immigration policy changes enacted after 9/11 for the Latino population in the United States, whereas Brown and Bean (Reference Brown, Bean, Givens, Freeman and Leal2009) show that the tightening of visa review processes led to a decline in the number of applications and admissions of international science and engineering students. Chebel d'Appollonia (Reference Chebel d'Appollonia2012) shows that both American and European governments implemented stricter border controls and even extraterritorial control mechanisms after 9/11. For her, however, these measures mostly reinforced security logics that have been around since the 1970s (see also Epifanio Reference Epifanio2011). Luedtke (Reference Luedtke, Givens, Freeman and Leal2009) also points to cross-border effects, arguing that 9/11 slowed the European Union's development towards a more harmonized European immigration and asylum regulations.

While these studies are qualitative in nature and focus on the 9/11 attacks as a special case, more recent empirical studies seek to provide quantitative and more general evidence regarding the effect of terrorism on migration policy making. Helbling and Meierrieks (Reference Helbling and Meierrieks2020) study the effect of transnational terrorism on migration policies in thirty OECD countries between 1980 and 2010. They find that higher levels of exposure to transnational terrorism are associated with stricter migration controls, but not stricter migration regulations regarding immigration eligibility criteria and conditions. The effects are particularly strong when the attacks are ferocious and occur after the end of the Cold War. For the same set of countries and time period, Bove, Böhmelt and Nussio (Reference Bove, Böhmelt and Nussio2020) show that states also implement more restrictive immigration policies when terrorist attacks happen in nearby countries. This once more points to potential diffusion effects associated with transnational terrorism. Finally, Choi (Reference Choi2019) studies the effect of terrorism on twenty-three immigration-receiving countries between 1970 and 2010; his sample includes developed (OECD) and developing countries (for example, Botswana) as well as several emerging markets (such as Brazil). In contrast to the former two studies, Choi (Reference Choi2019) finds that immigration policies are not responsive to terrorist activity.

In sum, these quantitative studies suggest that while transnational terrorism can indeed be policy relevant, this relationship is not necessarily straightforward. For one, there appear to be differences between rich and democratic (OECD) and less wealthy and democratic countries, which could explain the different findings of Helbling and Meierrieks (Reference Helbling and Meierrieks2020) and Bove, Böhmelt and Nussio (Reference Bove, Böhmelt and Nussio2020) in comparison to Choi (Reference Choi2019). For instance, electoral accountability and other democratic mechanisms may induce a more pronounced response to terrorism in OECD economies; however, future research is necessary to provide evidence to support this hypothesis. For another, countries may change their immigration policies in response to terrorism rather selectively (Helbling and Meierrieks Reference Helbling and Meierrieks2020). For instance, Avdan (Reference Avdan2014a) finds no evidence that increased global transnational terrorist activity reduces asylum recognition rates, suggesting that this humanitarian immigration policy is not affected by terrorism.

Indeed, while there may be political gains associated with framing migration as a security issue in response to terrorism, other factors may limit this process. For example, Avdan (Reference Avdan2014b) finds that transnational terrorism affects visa policies, but that this effect declines with increasing levels of economic interdependence between involved states, suggesting that other considerations (for example, gains from economic integration) also matter. Similarly, the political elite tends to be much more cosmopolitan than the ‘common people’ and thus less susceptible to possible security threats due to transnational terrorism and migration (Teney and Helbling Reference Teney and Helbling2014). For instance, Lahav, Messina and Vasquez (Reference Lahav, Messina and Vasquez2013) show that the immigration attitudes of members of the European Parliament were not affected by the 9/11 terrorist attacks.Footnote 9 What is more, powerful interest groups may actually be interested in more immigration. That is, framing migration as a security issue might contradict other policy goals such as the increase in the labor supply through immigration that is desired by powerful political players (such as business owners) (Boswell Reference Boswell, Givens, Freeman and Leal2009). Consequently, the policy preferences of cosmopolitan elites and pro-immigration interest groups that disfavor overly strict immigration policies will likely also be reflected in the eventual immigration policy regime.

The Effectiveness of Migration Policies as Counter-Terrorism Policies

Finally, we review the evidence on the effectiveness of stricter migration policies to combat terrorism. According to the rational-choice perspective introduced above, we should expect stricter policies to affect the terrorist calculus in ways that increase the material costs of terrorism. For instance, stricter policies may make it more difficult for terrorists to infiltrate other countries.

Böhmelt and Bove (Reference Böhmelt and Bove2020b) investigate the role of migration policies in moderating the effect of terrorism diffusion (via migration) for a sample of OECD economies. They find that ‘restrictive immigration policies may indeed make it more difficult for terrorism to diffuse across borders’ (Böhmelt and Bove Reference Böhmelt and Bove2020b, 176), suggesting that restrictive policies may help curb the risk of transnational terrorism. However, they also stress that this effect is only relevant to ‘target countries with exceptionally lax [immigration] regulations and control mechanisms’ (Böhmelt and Bove Reference Böhmelt and Bove2020b, 176), indicating that the overall effectiveness of migration policies as counter-terrorism tools is limited.

Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt (Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020) find that policies that restrict foreigners' rights (for example, by curtailing migrants' access to social welfare programs and the labor market) and enforce integration will actually lead to more terrorist activity. In particular, policies that are too repressive may backfire by alienating parts of the migrant population (Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt Reference Dreher, Gassebner and Schaudt2020). Choi (Reference Choi2018) analyzes the effect of migration policies on terrorism for ten Western industrialized democracies between 1970 and 2007 and obtains a similar finding. He likens the impact of migration policies on terrorism to a ‘double-edged sword’ (Choi Reference Choi2018, 21), finding that certain policies (such as governing the migrants' path to citizenship) may indeed encourage rather than deter terrorism. These findings suggest that in addition to affecting the material costs of terrorism (where higher costs would reduce terrorism), immigration policies may also affect the opportunity costs of terrorism, for example by aggravating migrants’ labor market participation or integration efforts. Potentially, then, an unwise mix of migration policies may produce undesired outcomes (more transnational terrorism), which will also run counter to incumbent politicians’ desire to be re-elected.

Bandyopadhyay and Sandler (Reference Bandyopadhyay and Sandler2014) also advocate a sound migration policy mix in their theoretical analysis. They introduce a model in which developed countries may curb terrorism at home by limiting unskilled and promoting skilled migration from developing (skill-scarce) countries. For instance, attracting high-skilled labor will increase the standard of living of high-skilled workers from developing countries (thus increasing their opportunity costs of violence), while at the same time depriving foreign terrorist organizations of the human capital they would need to stage successful cross-border terrorist attacks against the developed country (Bandyopadhyay and Sandler Reference Bandyopadhyay and Sandler2014).

Conclusion

The study of the migration–terrorism nexus first gained traction after the 9/11 attacks. More recent terrorist attacks (such as the 2015 Paris attacks), developments in migration (for example, the influx of refugees to Europe that started in 2015) and electoral events (for example, the election of Donald Trump and other anti-immigrant and tough-on-terror politicians) have motivated further analyses of the interplay among migration, terrorism, public policy and electoral politics. The study of the migration–terrorism nexus is thus a relatively young and dynamic research field. What is more, different disciplines (for example, political science, economics, sociology and social psychology) have contributed to this research field, which might make it even more difficult to keep track of the literature. Therefore, this review seeks to bring together different research strands on transnational terrorism and migration and provide a state-of-the-art overview of the literature, which can be summarized as follows.

First, there is little evidence that migration has an unconditional effect on terrorism that goes beyond a mere mechanical scale effect. Thus the evidence indicates that migration per se is not a Trojan horse of terrorism. However, migration may nevertheless lead to terrorism under unfavorable circumstances, especially when state capacity and socio-economic conditions in host countries are poor and detrimental to migrant and especially refugee integration. For instance, hostile conditions in refugee camps may be associated with more transnational terrorism.

Secondly, the evidence more strongly suggests that migrants are victimized by (right-wing) terrorism, for example serving as scapegoats for anti-immigration sentiment. This dimension of the migration–terrorism nexus, however, remains underappreciated in the public discourse and empirical studies.

Thirdly, even though the empirical connection between migration and terrorism is tenuous and by no means unconditional, such a link is still perceived to be valid in destination countries, which, in turn, has several consequences. The evidence suggests that terrorism (1) fosters anti-immigration sentiment (even though this effect can be short-lived), (2) benefits (right-wing) political parties that hold nativist views, while damaging the electoral position of incumbent governments and (3) leads to stricter migration policies, even though this effect may be context specific (for example, influenced by the relative strength of interest groups) and limited to specific types of migration policies. We develop a theoretical framework that links these three effects, arguing that transnational terrorism may create incentives for political incumbents to respond to terrorism with harsher migration policies to ensure their political survival.

Fourthly, there is little evidence that stricter migration policies actually result in less terrorism. Rather, certain policies that alienate the migrant population appear to incite terrorism. This may result in the worst of both worlds, with strict migration polices depressing economic growth (by reducing labor migration) and harming rather than contributing to domestic security.

Fifthly, the migration–terrorism nexus is transnational in nature. This not only refers to the cross-border flow of terrorist violence and people, but also to, for example, (1) the cross-border diffusion of fear and anti-immigrant resentment due to terrorism, (2) the adaption of stricter migration policies in response to terrorism in foreign countries and (3) feedback between terrorism and migration in sending and destination countries, for example, via diasporas and the cross-border flow of information and remittances.

We hope our literature overview provides researchers with a starting point for future research on the migration–terrorism nexus. In fact, we believe there are many potential areas for future research. For instance, when studying the conditional effects of migration on terrorism, it may be fruitful to also examine the roles of political factors (for example, interstate rivalries) and economic variables (such as trade interdependencies) in governing the migration–terrorism relationship. Similarly, it may be interesting to explicitly test (parts of) our theoretical framework introduced above (Figure 2), for example by investigating how terrorism could affect migration policy making and could thus be linked to electoral success. This framework could also be extended both theoretically and through empirical testing to account for potentially more complex linkages, for example by allowing for a reciprocal relationship between electoral outcomes induced by terrorism (for instance, the success of right-wing parties) and the development of anti-immigrant resentment. Considering migration policies in destination countries, there is also a need to more thoroughly study how specific regulations shape the integration, assimilation and participation of migrant populations. This could help explain why different migration policy mixes appear to share a different relationship with terrorism, which could consequently further improve immigration policy making. Finally, we would also like to encourage researchers to examine the interaction between migration and security policy making in the context of transnational terrorism in non-democratic countries, given that the existing evidence – also due to data constraints – tends to strongly focus on Western OECD democracies. For instance, it may be interesting to analyze whether non-democratic countries – by nature of being less sensitive to electoral demands – make different changes to their migration policy regime in response to transnational terrorism.

Transnational terrorism and international migration will likely continue to be contentious issues in the coming decades. Thus, in addition to inspiring further investigations of the migration–terrorism nexus, we also hope that our literature overview provides some guidance to policy makers as well as reassurance to the general public, for example concerning the alleged perilousness of migration as a Trojan horse of terrorism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tobias Böhmelt, Vincenzo Bove and two anonymous reviewers for their highly valuable comments.