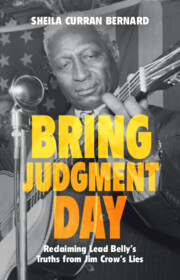

Many years ago, I spent some time helping to develop a documentary film about the life and legend of Huddie Ledbetter, better known as Lead Belly (1889–1949). An African American musician born in Louisiana, Ledbetter found fame but not fortune among New York City’s folk music and labor movements in the 1930s and 1940s. Among some 200 songs he recorded, he is perhaps best known for “Goodnight, Irene,” “In the Pines,” “Midnight Special,” and “Rock Island Line,” music popularized in the years after his death by a wide range of artists including Frank Sinatra, Odetta, Robert Plant, and Kurt Cobain. As sometimes happens, that documentary did not end up being produced. More recently, in 2010, I was hired to write a feature documentary for PBS based on Douglas A. Blackmon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Slavery by Another Name (Anchor Books, 2008). Immersing myself in this history of convict leasing and other forms of forced labor in the US South in the decades between the end of the Civil War and World War II, I kept thinking back to Huddie Ledbetter, incarcerated in both Texas and Louisiana in the years between 1915 and 1934. His first conviction, I remembered, was for “carrying a pistol,” a charge that I now understood might be one of the vague charges levied against African Americans, and rarely against whites, as a means of asserting white dominance while also securing a tightly controlled and virtually cost-free labor force in the industrializing South.1

Bring Judgment Day is structured around Ledbetter’s interaction with two white men, folklorist John Lomax and his son, Alan Lomax, who met the performer in 1933 and later spent six months with him, from late September 1934 through late March 1935. The Lomaxes introduced Ledbetter to national audiences, and they were the first to publish an account of his life, Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly (The Macmillan Company, 1936). The Lomax book, despite considerable inaccuracies, remains the main source of information about Ledbetter’s early life, and it sets the tone for the portrait of “Lead Belly” that continues to the present day, emphasizing a career of violence and incarceration. Subtitled “King of the Twelve-String Guitar Players of the World, Long-time Convict in the Penitentiaries of Texas and Louisiana,” the Lomaxes’ book is divided into two parts: Part I: The “Worldly N[–]” and Part II: The Sinful Songs. Part I, which runs to sixty-three pages, begins with a one-page chronology, followed by:

“Lead Belly Tells His Story” (pages 3–28), which purports to tell the story of Ledbetter before he met the Lomaxes, primarily in Ledbetter’s own words;

“Finding Lead Belly” (pages 29–33), about their meeting in prison;

“Traveling with Lead Belly” (pages 34–46), featuring Lead Belly’s work with the Lomaxes from late September 1934 to the end of the year, as they toured southern prisons and Black communities in search of music; and

“New York City and Wilton” (pages 47–64), about the events that followed after John Lomax arranged for Ledbetter to perform at the annual meeting of the Modern Language Association in Philadelphia, in December 1934, and the trio began to seek out academic and general audiences in the Northeast. The section drives to a split between John Lomax and Ledbetter, who returned to Louisiana in late March 1935.

Part II is a compilation of songs, with explanations from the Lomaxes and Ledbetter, with an emphasis on his prison repertoire.

The credibility accorded the early biography stems from the ways in which the authors, especially in the section titled “Lead Belly Tells His Story,” presented Ledbetter’s words as if they were a transcript of spoken, recorded speech, and therefore a reliable primary source. They used quotation marks and stereotyped dialect, such as “Yassuh, my papa he was a wuckah. I reckon I got it from him to be such a good wuckah in de penitenshuh,” even as they acknowledged that “[s]ometimes Lead Belly spoke in dialect, sometimes he didn’t.”2 They repeatedly emphasized the authenticity of this account. “In this book we present his life’s story and some of our novel experiences with him,” they wrote. “We print the story of his life before he met us, told in his own words, and we offer forty-nine of the songs he sang for us, together with the background of these songs, again, in many instances, in Lead Belly’s vernacular.”3 (Emphasis added.)

Reviewers and scholars, when the book was published, and in the decades since, have therefore relied upon the Lomax book as a credible primary source. This includes Kip Lornell and Charles Wolfe (The Life and Legend of Leadbelly, Da Capo Press, 1992), who noted that the Lomaxes had “a chance to do something hardly anybody else in folk music research in that day had done: record a singer’s total repertoire. Along the way, they would also record the singer’s autobiography, and comment about his songs.”4 It also includes John Lomax’s principal biographer, Nolan Porterfield (Last Cavalier: The Life and Times of John A. Lomax, University of Illinois Press, 1996), who credited the Lomaxes as the source of information for his own brief discussion of Ledbetter’s early years.5 More recently, Alan Lomax’s biographer, John Szwed (Alan Lomax: The Man Who Recorded the World, Penguin Books, 2010), wrote: “[Ledbetter] was also interviewed while he was being recorded to create an oral autobiography to be deposited in the Library of Congress.”6 Even the website for the Association for Cultural Equity, founded by Alan Lomax in 1983, suggests transcription.7

In fact, there is no transcript because there was no recording of an autobiography. In the first months of 1935, as they compiled the book, the Lomaxes recorded Ledbetter singing and at times speaking as he introduced or interrupted his songs to explain them, but the twelve-inch aluminum discs on which they recorded were expensive and scarce. In unpublished drafts of Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly, part of a collection donated to the Library of Congress in 2004, the Lomaxes made this clear as they explained how they documented Ledbetter’s story. (The “XXX” and crossed-out lines are in the original, and, although the excerpt ends mid-sentence, a follow-up page was not found in the archive.)

And here follows the story of the XXX “worldly n[–]” so far as we have been able to reconstruct it from his own reluctant, contradictory and intentionally confusing statements, from prison records, from a few scattering, brief and uninterested letters written by white men who have known him, and from the statement recollections of two of his women – Margaret, his childhood sweetheart, by whom he had his only child, who lives now in Dallas – and Martha, his present wife. whom we brought East and saw him legally marry. Some of the most interesting and significant stories we have had to omit because of the bad impression they would make all around their complete unprintableness. Some of the tales are told in his own idiom with as close an approximation to his narrative style as we could reconstruct.* There is certainly an over-emphasis of the violent and criminal side of Lead Belly’s life, and that because we had some basis (in his criminal record) for our questions. [inserted Therefore] we present this loosely woven texture of reconstructed stories and letters, not as accurate biographical material, but as a set of dramatic and exciting stories tales through which the

The asterisk leads to:

*Since neither of us could write shorthand, we soon despaired of taking notes on his stories as he told them. In writing long-hand we lost some portions of his each tale in being accurate in the attempting accuracy of idiom. of others. Besides, Lead Belly soon become embarrassed and unnatural when he saw us taking notes [italics is a handwritten insert from Alan]. We, therefore, wrote down the stories complete directly after he told them.

In the draft, the Lomaxes wrote that they had reconstructed these stories, “not as accurate biographical material but as a set of dramatic tales.” They acknowledged an “overemphasis” on Ledbetter’s “violent and criminal side,” because that is what they asked him about.8 However, in the book as published, this explanation is absent, and instead the biography’s authenticity is emphasized. As a result, the book became a source for other “biographical” accounts. This included Edmond Addeo and Richard Garvin’s self-described “historical novel,” The Midnight Special: The Legend of Leadbelly, published by Bernard Geis Associates in 1971. In their preface, the authors stated that the book was “the truth, so far as we can ever know it,”9 although in a 1990 interview with Kip Lornell, Addeo noted that they had taken “some literary liberties, dramatic liberties” and included “scenes we made up … out of whole cloth, just for dramatic continuity.”10 A few years later, screenwriter Ernest Kinoy seems to have been influenced both by the Lomax book and by The Midnight Special as he wrote the screenplay for Leadbelly (Paramount Pictures, 1976), directed by Gordon Parks. Although the film is a fictionalized account of Ledbetter’s life, reviewers often saw it as biography.11

What is especially troubling about the Lomaxes’ framing of Huddie Ledbetter is that by casting one man as the violent center of the narrative, they erased the context of racial terror that marked the economic and political dominance of white southerners in the decades following the Civil War. It was Ledbetter’s personal traits and actions, the Lomaxes argued – and most audiences accepted this as fact – that led to his repeated incarceration. Conversely, it was the Lomaxes’ personal traits and actions, and not any sort of privilege or the exclusion of others, that made them deserving of the opportunities and advancement that they and millions of other white southerners enjoyed in education, housing, and employment. This erasure can be found in liner notes, articles, books, and websites, up to the present day, even those intended to celebrate the performer. “Unfortunately, Ledbetter had a violent temper and was in and out of prison several times in the course of his life,” reports the Bullock Museum in Austin.12 The website of the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame, into which Ledbetter was inducted in 2008, reads: “Possessing a legendary quick temper, he was arrested and convicted of murder in Texas in 1917 and sentenced to 20 years imprisonment.”13 Until it was changed in 2019, Ledbetter’s biography on the website of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, into which he was inducted in 1988, read, “A man possessed with a hot temper and enormous strength, Lead Belly spent his share of time in Southern prisons.”14

It is true that Huddie Ledbetter spent several years in captivity. He served on a county chain gang in 1915 and was incarcerated in state penitentiaries in Texas (1918–1925) and Louisiana (1930–1934) and in jail at Rikers Island in New York (1939). Yet, without historical context, even those who celebrate Ledbetter’s ability to survive his time in these institutions are robbed of an opportunity to understand not only the performer but also the nation in which he came of age. At the same time, to write a biography of Ledbetter’s early life without acknowledging the Lomaxes and their engagement with him, including their writing of Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly, would be a mistake. First and foremost, it is the Lomax narrative that has defined Ledbetter for the better part of a century. Exploring the choices that they made as they created a persona for Ledbetter, and the ease with which their version of him was accepted and augmented by others, often in highly negative ways, is an important part of Bring Judgment Day. Reporters, radio producers, motion picture executives, academics, and the general public willingly went along with what historian Hazel Carby described as “[t]he political project of the Lomaxes,” which was “to cast the black male body into the shape of an outlaw. John Lomax intended to recover an unadulterated form of black music, and in the process actually invented a particular version of black authenticity.”15

Additionally, there are elements of the Lomaxes’ writings that can be verified and prove useful, including both the description of their travels with Huddie Ledbetter and even some discussion of his early life. Notably, where their book seems most aligned with Ledbetter’s past, it is when he talked about music, storytelling, and good times with family and friends. Where it is often demonstrably false is when he is quoted as describing terrible acts of violence, always “against his own people,” as the Lomaxes put it, as if to reassure themselves and their white readers. Certainly, some of this was Ledbetter himself being selective about what he shared, understanding, as did the Lomaxes, that any reported charge that he had been violent toward white people would end the possibility of a national career. Some of Ledbetter’s songs contain elements of autobiography; some also contain lyrics of violence, notably against women, but the extent to which they should be trusted as character-based is unclear. Much of his repertoire was drawn and adapted from material that had been performed by others he’d encountered, and the choices of which songs he would perform, which he would record, and which he would release to the public were generally made by white gatekeepers, whether prison officials, the Lomaxes, or northern record producers. Further confusing the narrative, Ledbetter himself liked to share what he called “tall tales,” as they were known “down home.”16 The Lomaxes, too, could be selective and at times deceptive when describing their own actions. John Lomax, in particular, is an unreliable narrator, often presenting himself as being drawn into events rather than orchestrating them, even when evidence shows otherwise. In addition, throughout the time he spent “interpreting” Ledbetter for the benefit of audiences and the press and in Negro Folks Songs as Sung by Lead Belly, Lomax emphasized his knowledge and expertise while continually minimizing the achievements, talent, and expertise of Ledbetter. At times, though, he paints such a negative portrait of himself in the book that the results gain credibility.

Bring Judgment Day is structured around the relationship of Huddie Ledbetter and John Lomax, primarily between 1933 and 1935, while also drawing on the historical record of Ledbetter’s life from 1889, when he was born, to the mid-1930s, when he and his wife, Martha Promise Ledbetter, by then independent of John Lomax, permanently relocated to New York City. Ultimately, though, this book is Ledbetter’s. The Lomaxes, for better and worse, played an important role in bringing his music to new audiences, but it was Ledbetter himself who rose to this opportunity and challenge, as he had so often in the past, and then moved beyond it. As a performer, he was a link between the past and the future, a collector and promoter of America’s tremendously diverse musical heritage and an innovator whose creative drive played a vital role in shaping the foundation not only of modern American culture but also of world culture. To truly understand that culture, a fresh look at the early history of this important American musician is essential – today more than ever. As political pressure is building to limit and even criminalize efforts to teach evidence-based history of the nation’s past, a book that re-examines the life and legacy of Huddie Ledbetter in the broader context of the United States’ social, political, and legal systems is especially timely.