Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documented the first United States (US) laboratory-confirmed case of COVID-19 on January 22, 2020 [Reference Stokes, Zambrano and Anderson1]. By June 2020, the US had over 3 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, and low-income neighborhoods showed high positivity rates for COVID-19 testing (30%–35%), compared to nationwide rates of 8.8% [Reference Servick2]. COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths are disparate across racial and ethnic groups in the US, disproportionately impacting minority communities [Reference Thebault, Tran and Williams3]. These disparities are magnified in certain areas of the US. For example, majority–minority counties in the US report infection rates 300% higher than that of White-majority counties, and death rates nearly 600% higher [Reference Smith and Medalia4].

In June 2020, Northwest Arkansas, and in particular Benton and Washington counties, was one of the highest COVID-19 hot spots in the US. The racial and ethnic disparities of COVID-19 cases are so stark that the CDC conducted an in-depth community-level investigation in June and July 2020. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) followed suit in early August 2020. According to the CDC’s July 2020 report, 45% of all adult cases in Northwest Arkansas identified as Hispanic/Latinx, and 19% were Pacific Islander [5]. These communities only account for 17% and 2.4%, respectively, of the two-county population. Latinx and Pacific Islander community members encounter many socioeconomic challenges, including low educational attainment and unstable and dense housing. Latinx and Pacific Islander community members are often employed in low-wage jobs, primarily in the poultry industry, which are deemed essential and do not allow them to work from home [5,Reference Harris and Jones6].

For the past 5 years, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) has worked with Latinx and Pacific Islander community leaders and organizations to address health disparities and promote translational research. As the state’s only academic health center, we leverage a community-engaged approach to build trust between academic health centers and community stakeholders [Reference Wallerstein and Duran7–Reference Minkler12]. These partnerships are funded by the Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (CTSA) at UAMS and the CDC’s Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) program. These partnerships have long-standing community advisory boards and conducted several projects and research initiatives together. Details about the partnership and the collaborative work of the community–academic partnership are published elsewhere [Reference McElfish, Kohler and Smith13].

The mission of the CTSA at UAMS is to develop new knowledge and novel approaches that will measurably address the complex health challenges of rural and underrepresented populations. Grant resources provide training and support for community-based participatory research, community engagement, plain language communications, and the expansion of research in special populations [Reference Huff-Davis, Cornell, McElfish and Kim Yeary14,Reference Stewart, Spencer, Huff Davis, Hart and Boateng15].

The REACH program has a three-pronged focus for advancing REACH: supporting culturally tailored interventions to address preventable health conditions; linking community and clinical efforts to increase access to health care and preventive care programs at the community level; and the implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of practice- and evidence-based strategies to reduce health disparities in chronic conditions [16].

In early 2020, community-engaged partnerships utilized their collaborative capacity to address COVID-19 disparities in the Latinx and Pacific Islander communities. No CDC or NIH funding was spent on COVID-19-specific activities outlined in this article. However, partners continue to leverage existing community-based capacity to engage the Pacific Islander and Latinx community while developing and executing a COVID-19 Response Strategy to Reduce Health Disparities. Funding was provided through the Arkansas Department of Health’s distribution of CARES act funding [17]. This strategy is described below.

A COVID-19 Strategy to Reduce Health Disparities for the Pacific Islander and Latinx communities in Northwest Arkansas

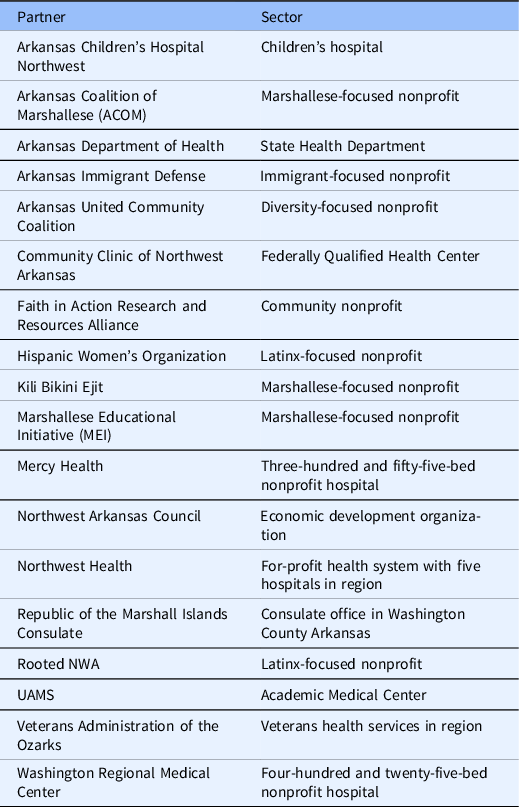

Since March 2020, 18 key community partners have had weekly meetings, and there is often daily communication between partners. Partners collaboratively developed a COVID-19 Response Strategy to ensure coordinated effort for Latinx and Pacific Islander communities with four interrelated strategies: health education, testing, contact tracing, and supported quarantine/case management. Partners are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Community partners and the sector partners represent

Strategy 1: Health education and prevention

Based on the recommendations from the CDC’s July 2020 report, partners co-developed a communications strategy designed specifically for COVID-19. This strategy covers four areas: prevention, testing, quarantine, and follow-up care. Prevention communication focuses on behaviors and practices individuals can take to reduce their risk of infection, including when and how to wear a mask, hand washing, and how to stay connected with family and friends while maintaining an appropriate physical distance.

Communications about COVID-19 testing focuses on describing when and where people can be tested, provides bilingual videos for those places doing self-administered testing swabs, provides information about costs, and informs on safe behaviors while waiting for test results. The quarantine and isolation guidance focuses on criteria for when quarantine and self-isolation are appropriate and explains the available social services to support those efforts. Follow-up care covers symptom management and when and how to seek additional care if needed. Partners also developed targeted communications for high-risk community members, specifically addressing pregnancy, diabetes, mental health, and asthma. Small business and faith-based tool kits were created and have been distributed to more than 120 local small businesses within the Latinx and Pacific Islander communities. Communications primarily focus on nontraditional and unpaid media.

All communications are in English, Spanish, and Marshallese (the native language of most Pacific Islanders in Northwest Arkansas) and leverage local Latinx and Pacific Islander community leaders. The communications materials can be found at https://northwestcampus.uams.edu/ochrcovid/. An outline of communications tools developed as of November 30 is listed in Table 2. New communication tools are added frequently.

Table 2. Types and estimated reach of COVID-19 communications materials

Strategy 2: Testing

The COVID-19 Strategy to Reduce Health Disparities for the Pacific Islander and Latinx communities is led by the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), and employs the resources of UAMS, Arkansas Department of Health offices, and local healthcare providers for testing. Based on the CDC July 2020 report, testing primarily focuses on organizations and/or neighborhoods with a high number of cases so that partners can quickly target hot spots and reduce the spread. Targeted serial testing ensures rapid testing of all contacts of known or suspected COVID-19 cases. When a positive case is identified, all of their contacts are offered in-home testing. If the contact(s) prefer to not have testing at their home, they are directed to drive-through testing centers. For in-home testing, a nurse-led team of healthcare workers provide testing to contacts and all household members without contacts leaving their home. In addition, drive-through testing centers are distributed throughout two counties at local healthcare organizations and mobile testing teams conduct tests at churches, worksites, and housing complexes. Most importantly, all testing locations have bilingual staff. Community partners play an important role in helping identify the community-based location for mobile testing and encouraging community members to get tested at any of the testing locations.

Strategy 3: A dedicated contact tracing center with bilingual workers

The COVID-19 Strategy to Reduce Health Disparities for the Pacific Islander and Latinx communities focuses on establishing a bilingual contact tracing center in the region that fully integrates with the Arkansas Department of Health. The contact tracing center is staffed with bilingual contact tracing staff. The bilingual contact tracing center utilizes the same software, policies, and procedures as the Arkansas Department of Health and includes a designated process of identification and follow-up of all persons who may have come into contact with a person infected with COVID-19.

Since a positive test for COVID-19 is a mandatory reportable diagnosis to the Arkansas Department of Health, any new cases are reported, and those whose preferred language is Marshallese or Spanish are referred to the bilingual contact tracing center. Bilingual staff at the contact tracing center reach out to the case and determine direct contacts for the case during the period from 2 days before symptoms started until the case quarantined. The case is asked to inform all contacts that someone from the contact tracing center will be calling them. After the case alerts those contacts to expect a call, contact tracing staff will contact them to begin the screening process and advise quarantine. This quarantine applies to their households as well as any other direct contacts. This initial survey triggers a 14-day tracking period, which consists of daily communication with each contact under quarantine. All contact tracing data are entered into the Arkansas Department of Health software and uploaded to the department at the end of each day. All cases and contacts receive education about how to isolate (Strategy 1). Contacts are offered testing (Strategy 2). All cases and contacts who need assistance with food, housing, and medication work with a social worker and bilingual navigators to identify resources to meet those needs (Strategy 4).

Strategy 4: Enhanced case management and supported quarantine

A COVID-19 diagnosis often exacerbates the socioeconomic challenges that the Pacific Islander and Latinx populations face in Northwest Arkansas. Bilingual social workers, nurses, and community health navigators make up the enhanced case management team. It is critical to provide support services for both cases and contacts as they self-quarantine. Needed support includes essentials like food and medications, coordination with worksites, and coordination with community behavioral health services. Standard contact tracing encourages contacts to stay home and maintain distance from others until 14 days after their last exposure. The enhanced case management process elevates this with follow-up communication with the person who has COVID-19 and contacts to follow all quarantine guidelines. The enhanced case management also discusses their health and inquires about new symptoms. The staff provides resources, education, information, and connection with health care and community-based support organizations. They arrange for both food deliveries and prescription drug refills, if needed, to facilitate the contacts’ ability to remain at home. The nonprofit organizations listed in Table 1 have funding and actively take part in ensuring cases and contacts have the support they need.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 Strategy to Reduce Health Disparities for the Pacific Islander and Latinx communities in Northwest Arkansas demonstrates how community-based participatory research and programmatic networks funded by NIH and the CDC can be quickly leveraged to address COVID-19, which has disproportionately affected Latinx and Pacific Islander community members. This example shows the importance of building and sustaining community-based research and programmatic networks. The regional collaborative in Northwest Arkansas plans to leverage their network in the future to ensure Pacific Islander and Latinx communities have the opportunity to participate in vaccine studies and the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines.

Acknowledgments

These efforts are supported in part by CARES Act funding (PAM) and the Blue and You Foundation of Arkansas (PAM). The community-based participatory research team was provided by a Translational Research Institute grant (#1U54TR001629-01A1) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (PAM) and the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) grant (#1NU58DP006595-01) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (PAM). We thank the numerous community partners who have worked on these efforts. These partners are listed in Table 1. We specifically thank the Northwest Arkansas Council and Community Clinic for their leadership in the effort.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.